Clef

A clef (from the French for "key") is a musical symbol used to indicate the pitch of written notes.* Placed on one of the lines at the beginning of the staff, it indicates the name and pitch of the notes on that line. This line serves as a reference point by which the names of the notes on any other line or space of the staff may be determined.

The three types of clef

There are three types of clef used in modern music notation: F, C, and G. Each type of clef assigns a different reference note to the line on which it is placed.

Once one of these clefs has been placed on one of the lines of the staff, the other lines and spaces can be read in relation to it.

The use of three different clefs makes it possible to write music for all instruments and voices, even though they may have very different tessituras (that is, even though some sound much higher or lower than others). This would be difficult to do with only one clef, since the modern staff has only five lines, and the number of pitches that can be represented on the staff, even with ledger lines, is not nearly equal to the number of notes the orchestra can produce. The use of different clefs for different instruments and voices allows each part to be written comfortably on the staff with a minimum of ledger lines. To this end, the G-clef is used for high parts, the C-clef for middle parts, and the F-clef for low parts - with the important exception of transposing parts, which are written at a different pitch than they sound, often even in a different octave.

The positions of the clefs

In order to facilitate writing for different tessituras, any of the clefs may theoretically be placed on any of the lines of the staff. The further down on the staff a clef is placed, the higher the tessitura it is for; conversely, the higher up the clef, the lower the tessitura.

Since there are five lines of the staff, and three clefs, it might seem that there would be a total of fifteen possible clefs. Six of these, however, are redundant clefs (for example, a G-clef on the third line would be exactly the same as a C-clef on the first line). That leaves nine possible distinct clefs, all of which have been used historically: the G-clef on the two bottom lines, the F-clef on the three top lines, and the C-clef on any line of the staff except the topmost, earning the name of "movable C-clef". (The C-clef on the topmost line is redundant because it is exactly equivalent to the F-clef on the third line; both ways of writing this clef have been used.)

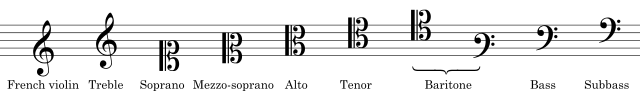

Each of these clefs has a different name based on the tessitura for which it is best suited.

Nowadays, only four clefs are used regularly: the treble clef, the bass clef, the alto clef, and the tenor clef. Of these, the treble and bass clefs are by far the most common.

Individual clefs

Here follows a complete list of the clefs, along with a list of instruments and voice parts notated with them. Each clef is shown in its proper position on the staff, followed by its reference note.

An obelisk (†) after the name of a clef indicates that that clef is now obsolete.

G-clefs

The treble clef

When the G-clef is placed on the second line of the staff, it is called the "treble clef". This is by far the most common clef used today, and the only G-clef still in use. For this reason, the terms G-clef and treble clef are often seen as synonymous. It was formerly also known as the "violin clef".

This clef is used for the violin, flutes, oboe, English horn, all clarinets, all saxophones, horn, trumpet, guitar, vibraphone, xylophone; for the upper part of keyboard instruments like the piano, organ, harp, and harpsichord (of which the lower part is usually written in the bass clef); for the highest notes played by the cello (the old convention was to write an octave higher, unless preceded by a tenor clef), bassoon, trombone (which otherwise use the bass and tenor clefs), and viola (which otherwise uses the alto clef); and for the soprano, mezzo-soprano, alto, and tenor voices.

The French violin clef†

When the G-clef is placed on the first line of the staff, it is called the "French clef" or "French violin clef".

This clef is no longer used. Formerly, it was used by the flute and violin, especially in parts published in France in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

F-clefs

The bass clef

When the F-clef is placed on the fourth line, it is called the "bass clef". This is the only F-clef used today, so that the terms "F-clef" and "bass clef" are often regarded as synonymous.

This clef is used for the cello, double bass, bass guitar, bassoon, contrabassoon, trombone, tuba, and timpani; for the lower part of keyboard instruments like the piano, organ, and harpsichord (of which the upper part is usually written in treble clef); and for the lowest notes of the horn; and the baritone and bass voices.

The baritone clef†

When the F-clef is placed on the third line, it is called the baritone clef.

This clef is no longer used. Formerly, it was used to write the baritone part in vocal music.

The subbass clef†

When the F-clef is placed on the fifth line, it is called the subbass clef.

This clef is no longer used. Formerly, it was used to write low bass parts, e.g. in the works of Heinrich Schütz.

C-clefs

The alto clef

When the C-clef is placed on the third line of the staff, it is called the alto clef.

This clef is currently used only for the viola, and for this reason is sometimes called the viola clef. Formerly, it was used by the alto trombone (Russian composers persisted in this practice well into the twentieth century), the tenor viola da gamba, the alto part in vocal music, and by the oboe in certain Bach works.

The tenor clef

When the C-clef is placed on the fourth line of the staff, it is called the tenor clef.

This clef is used for the upper ranges of the bassoon, cello, euphonium, double bass and trombone (which all use the bass clef in their lower and middle ranges, and in their extreme high ranges, the treble clef as well). Formerly, it was used by the tenor part in vocal music.

The baritone clef†

Occasionally in the past, the C-clef was placed on the fifth line, and it is called the baritone-clef, like the baritone F-clef on the third line, to which it is exactly equivalent. Because of this equivalency, it was rarely used in the past; the baritone F-clef was used instead.

The mezzo-soprano clef†

When the C-clef is placed on the second line of the staff, it is called the mezzo-soprano clef.

This clef is no longer used. Formerly, it was used in vocal music to write mezzo-soprano parts.

The soprano clef†

When the C-clef occurs on the first line of the staff, it is called the soprano clef.

This clef is no longer used. Formerly, it was used in vocal music to write soprano parts.

Other clefs

Octave clefs

Sometimes a small 8 is attached to a clef to show that an instrument reads an octave above or below concert pitch. This can be usually found in tenor parts in SATB settings, in which there is a G clef with an 8 below it, indicating the pitches are sung an octave below. Starting around 1900 Dawson in Boston led an attempt to popularise a version with a C clef on the 3rd space.

Neutral clef

The neutral or percussion clef is not a clef in the same sense that the F, C and G clefs are. It is simply a convention that indicates that the lines and spaces of the staff are each assigned to a percussion instrument with no precise pitch. With the exception of some common drum-kit and marching percussion layouts, a legend or indications above the staff are necessary to indicate what is to be played. Percussion instruments with identifiable pitches do not use the neutral clef, and timpani (notated in bass clef) and mallet percussion (noted in treble clef or on a grand staff) are usually notated on different staves than unpitched percussion.

Staves with a neutral clef do not always have five lines. Commonly, percussion staves only have one line, although other configurations can be used.

The neutral clef is sometimes used when non-percussion instruments play non-pitched extended techniques, such as hitting the body of a violin or cello.

Tablature

For guitars and other plucked instruments it is possible to notate tablature in place of ordinary notes. In this case, a TAB-sign is often written instead of a clef. The number of lines of the staff is not necessarily five: one line is used for each string of the instrument (so, for standard 6-stringed guitars, six lines would be used). Numbers on the lines show on which fret the string should be played. This Tab-sign, like the Percussion clef, is not a clef in the true sense, but rather a symbol employed instead of a clef.

Historical note

The clefs developed at the same time as the staff, in the 10th century. Originally, instead of a special clef symbol, the reference line of the staff was simply labeled with the name of the note it was intended to bear: either G, F, or C. These were the 'clefs' used for Gregorian chant. Over time, the shapes of these letters became stylized, eventually resulting in the shapes we have today. (Historically, two other clefs have been used as well, the D-clef and the Gamma-clef, indicating the notes now represented by the third and first lines of the bass clef, respectively: but these fell out of use.)

Several variant shapes of the different clefs persisted until very recent times. The F-clef was until very recently written like this: File:Oldbassclef.png.

The C-clef was formerly written in a more angular way than now, and many people still use this, or a further simplified K-shape, when writing the clef by hand. The flourish at the top of the G-clef probably derives from a cursive S for "sol", the name for "G" in solfege[1].

C-clefs were formerly used to notate vocal music, a practice which dwindled away during the late 19th century. The soprano voice was written in 1st line C clef (soprano clef), the alto voice in 3rd line C clef (alto clef), the tenor voice in 4th line C clef (tenor clef) and the bass voice in 4th line F clef (bass clef).

In more modern publications, 4 part harmony on parallel staves is usually written more simply as:

- S(oprano) = treble clef (2nd line G clef)

- A(lto) = treble clef

- T(enor) = treble clef with an "8" below or a double treble clef

- B(ass) = bass clef (4th F clef)

or is reduced to two staves, one with the treble and one with the bass clef.

Further uses

One more use of the clefs is training in sight reading: the ability to read in any clef is useful for being able to transpose on sight (see sight transposition), although in that case the tessitura implied by the given clef must be ignored. It is then only necessary to use 7 clefs, so that any written note can take any of the 7 different names (A, B, C, D, E, F, G). Students in French and Belgian conservatories and music schools, amongst others, are thoroughly drilled in this kind of exercise and solfeggios meant for use in those institutions are about the only scores where one will find nowadays a 1st line or 2nd line C clef or a 3rd line F clef. For some reason, the 3rd line F clef (the baritone clef) is preferred in the French and Belgian pedagogical tradition to the equivalent 5th line C clef. This may have something to do with the fact that very early medieval scores had only 4 line staffs, hence possibly the avoidance in some particularly traditionalist circles to write a clef on the 5th line, though this is arguably more likely due to the visual impact of the fact that the 3rd line F clef is contained entirely within the staff whilst half of the 5th line C clef protrudes above it.

References

- Dandelot, Georges. Manuel pratique pour l'étude des clefs. Revised by Bruno Giner and Armelle Choquard. Eschig 1999.

- Kidson, Frank. The Evolution of Clef Signatures. In 'The Musical Times', Vol. 49, No. 785 (Jul. 1, 1908), pp. 443-444.

- Kidson, Frank. The Evolution of Clef Signatures (Second Article). In 'The Musical Times, Vol. 50, No. 793 (Mar. 1, 1909), pp. 159-160

- Morris and Ferguson. Preparatory Exercises in Score-Reading.

Footnotes

- Strictly speaking, the clef does not indicate the 'pitch' of the notes, but their 'names'; the actual pitch may vary according to the tuning system or pitch standard employed.

- ^ Kidson, Frank. The Evolution of Clef Signatures.