Kashmir

34°30′N 76°00′E / 34.5°N 76°E

Kashmir (Kashmiri: کٔشِیر कॅशीर, Urdu: کشمیر, IPA: [kəʃˈmiːr] ()) is the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent. Historically the term Kashmir was used to refer to the valley lying between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal range. Today Kashmir refers to a larger area that includes the Indian-administered regions of Kashmir valley, Jammu and Ladakh, the Pakistani administered regions Northern Areas and Azad Kashmir, and the Chinese administered region of Aksai Chin.

Kashmir was originally an important centre of Hinduism and later of Buddhism. Half-way through the 12th century AD, Shah Mirza became the first Muslim ruler of Kashmir and started the line Salatin-i-Kashmir.[1] For the next five centuries Kashmir had Muslim rulers, which included Sultan Sikandar (also known as Butshikan, or "iconoclast") who ascended the throne in 1398, Zain-ul-abidin, who became the ruler in 1420, the Mughals, whose rule lasted until 1751, and the Afghan Durranis, who ruled Kashmir from 1752 until 1820.[1] That year, the Sikhs under Ranjit Singh, annexed Kashmir, and held it until 1846,[1] at which time, the Dogras, starting with Gulab Singh, became the rulers of Kashmir upon the purchase of the region from the British under the Treaty of Amritsar. The Dogra Rule (under the paramountcy, or tutelage, of the British Crown) lasted until 1947, when the former princely state became a disputed territory, now administered by three countries, India, Pakistan, and China.

The Kashmir region has long been a Muslim majority region. In the 1901 Census of the British Indian Empire, Muslims constituted 74.16% of the total population of the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu, Hindus, 23.72%, and Buddhists, 1.21%. The Hindus were found mainly in Jammu, where they constituted a little less than 50% of the population.[2] In the Kashmir Valley, Muslims constituted 93.6% of the population and Hindus 5.24%.[2] These percentages have remained fairly stable for the last 100 years.[3] Forty years later, in the 1941 Census of British India, Muslims accounted for 93.6% of the population of the Kashmir Valley and the Hindus for 4%.[3] In 2003, the percentage of Muslims in the Kashmir Valley was 95%[4] and those of Hindus 4%; the same year, in Jammu, the percentage of Hindus was 66% and those of Muslims 30%.[4] Among well-known people of Kashmiri lineage are Muhammad Iqbal, the Urdu poet, Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, and Nawaz Sharif, former prime minister of Pakistan.

Etymology

The Nilamata Purana describes the Valley's origin from the waters, a fact corroborated by prominent geologists, and shows how the very name of the land was derived from the process of desiccation - Ka means "water" and Shimir means "to desiccate". Hence, Kashmir stands for "a land desiccated from water". There is also a theory which takes Kashmir to be a contraction of Kashyap-mira or Kashyapmir or Kashyapmeru, the "sea or mountain of Kashyapa", the sage who is credited with having drained the waters of the primordial lake Satisar, that Kashmir was before it was reclaimed. The Nilamata Purana gives the name Kashmira to the Valley considering it to be an embodiment of Uma and it is the Kashmir that the world knows today. The Kashmiris, however, call it Kashir, which has been derived phonetically from Kashmir, as pointed out by Aurel Stein in his introduction to the Rajatarangini.

History

By the early 19th century, the Kashmir valley had passed from the control of the Durrani Empire of Afghanistan, and four centuries of Muslim rule under the Mughals and the Afghans, to the conquering Sikh armies. Earlier, in 1780, after the death of Ranjit Deo, the Raja of Jammu, the kingdom of Jammu (to the south of the Kashmir valley) was captured by the Sikhs under Ranjit Singh of Lahore and afterwards, until 1846, became a tributary to the Sikh power.[5] Ranjit Deo's grand-nephew, Gulab Singh, subsequently sought service at the court of Ranjit Singh, distinguished himself in later campaigns, especially the annexation of the Kashmir valley by the Sikhs army in 1819, and, for his services, was created Raja of Jammu in 1820. With the help of his able officer, Zorawar Singh, Gulab Singh soon captured Ladakh and Baltistan, regions to the east and north-east of Jammu.[5] In 1845, the First Anglo-Sikh War broke out, and Gulab Singh "contrived to hold himself aloof till the battle of Sobraon (1846), when he appeared as a useful mediator and the trusted advisor of Sir Henry Lawrence. Two treaties were concluded. By the first the State of Lahore (i.e. West Punjab) handed over to the British, as equivalent for (rupees) one crore of indemnity, the hill countries between Beas and Indus; by the second[6] the British made over to Gulab Singh for (Rupees) 75 lakhs all the hilly or mountainous country situated to the east of Indus and west of Ravi" (i.e. the Vale of Kashmir).[5] Soon after Gulab Singh's death in 1857, his son, Ranbir Singh, added the emirates of Hunza, Gilgit and Nagar to the kingdom.

The Princely State of Kashmir and Jammu (as it was then called) was constituted between 1820 and 1858 and was "somewhat artificial in composition and it did not develop a fully coherent identity, partly as a result of its disparate origins and partly as a result of the autocratic rule which it experienced on the fringes of Empire."[8] It combined disparate regions, religions, and ethnicities: to the east, Ladakh was ethnically and culturally Tibetan and its inhabitants practised Buddhism; to the south, Jammu had a mixed population of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs; in the heavily populated central Kashmir valley, the population was overwhelmingly Sunni Muslim, however, there was also a small but influential Hindu minority, the Kashmiri brahmins or pandits; to the northeast, sparsely populated Baltistan had a population ethnically related to Ladakh, but which practised Shi'a Islam; to the north, also sparsely populated, Gilgit Agency, was an area of diverse, mostly Shi'a groups; and, to the west, Punch was Muslim, but of different ethnicity than the Kashmir valley.[8] After the Indian Rebellion of 1857, in which Kashmir sided with the British, and the subsequent assumption of direct rule by Great Britain, the princely state of Kashmir came under the paramountcy of the British Crown.

Ranbir Singh's grandson Hari Singh, who had ascended the throne of Kashmir in 1925, was the reigning monarch in 1947 at the conclusion of British rule of the subcontinent and the subsequent partition of the British Indian Empire into the newly independent Union of India and the Dominion of Pakistan. As parties to the partition process, both countries had agreed that the rulers of princely states would be given the right to opt for either Pakistan or India or—in special cases—to remain independent. In 1947, Kashmir's population "was 77 per cent Muslim and it shared a boundary with Pakistan. Hence, it was anticipated that the Maharaja would accede to Pakistan, when the British paramountcy ended on 14-15 August. When he hesitated to do this, Pakistan launched a guerilla onslaught meant to frighten its ruler into submission. Instead the Maharaja appealed to Mountbatten[9] for assistance, and the Governor-General agreed on the condition that the ruler accede to India."[10] Once the Maharaja signed the Instrument of Accession, which included a clause added by Mountbatten asking that the wishes of the Kashmiri people be taken into account, "Indian soldiers entered Kashmir and drove the Pakistani-sponsored irregulars from all but a small section of the state. The United Nations was then invited to mediate the quarrel. The UN mission insisted that the opinion of Kashmiris must be ascertained, while India insisted that no referendum could occur until all of the state had been cleared of irregulars."[10]

In the last days of 1948, a ceasefire was agreed under UN auspices; however, since the plebiscite demanded by the UN was never conducted, relations between India and Pakistan soured,[10] and eventually led to two more wars over Kashmir in 1965 and 1999. India has control of about half the area of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir; Pakistan controls a third of the region, the Northern Areas and Azad Kashmir. According to Encyclopaedia Britannica, "Although there was a clear Muslim majority in Kashmir before the 1947 partition and its economic, cultural, and geographic contiguity with the Muslim-majority area of the Punjab (in Pakistan) could be convincingly demonstrated, the political developments during and after the partition resulted in a division of the region. Pakistan was left with territory that, although basically Muslim in character, was thinly populated, relatively inaccessible, and economically underdeveloped. The largest Muslim group, situated in the Vale of Kashmir and estimated to number more than half the population of the entire region, lay in Indian-administered territory, with its former outlets via the Jhelum valley route blocked."[11]

The UN Security Council on 20 January 1948 passed Resolution 39, establishing a special commission to investigate the conflict. Subsequent to the commission's recommendation, the Security Council ordered in its Resolution 47, passed on 21 April 1948, that the invading Pakistani army retreat from Jammu & Kashmir and that the accession of Kashmir to either India or Pakistan be determined in accordance with a plebiscite to be supervised by the UN. In a string of subsequent resolutions, the Security Council took notice of the continuing failure to hold the plebiscite.

The Government of India holds that the Maharaja signed a document of accession to India October 26, 1947. Pakistan has disputed whether the Maharaja actually signed the accession treaty before Indian troops entered Kashmir. Furthermore, Pakistan claims the Indian government has never produced an original copy of this accession treaty and thus its validity and legality is disputed. However, India has produced the instrument of accession with an original copy image on its website. Alan Campbell-Johnson, the press attache to the Viceroy of India states that "The legality of the accession is beyond doubt."[12]

The eastern region of the erstwhile princely state of Kashmir has also been beset with a boundary dispute. In the late 19th- and early 20th centuries, although some boundary agreements were signed between Great Britain, Afghanistan and Russia over the northern borders of Kashmir, China never accepted these agreements, and the official Chinese position did not change with the communist takeover in 1949. By the mid-1950s the Chinese army had entered the north-east portion of Ladakh.[11] : "By 1956–57 they had completed a military road through the Aksai Chin area to provide better communication between Xinjiang and western Tibet. India's belated discovery of this road led to border clashes between the two countries that culminated in the Sino-Indian war of October 1962."[11] China has occupied Aksai Chin since 1962 and, in addition, an adjoining region, the Trans-Karakoram Tract was ceded by Pakistan to China in 1965.

Current status and Political Divisions

The region is divided among three countries in a territorial dispute: Pakistan controls the northwest portion (Northern Areas and Azad Kashmir), India controls the central and southern portion (Jammu and Kashmir) and Ladakh, and China controls the northeastern portion (Aksai Chin and the Trans-Karakoram Tract). India controls the majority of the Siachen Glacier (higher peaks), whereas Pakistan controls the lower peaks. India controls 101,387 km² of the disputed territory, Pakistan 85,846 km² and China, the remaining 37,555 km².

Though these regions are in practice administered by their respective claimants, India has never formally recognised the accession of the areas claimed by Pakistan and China. India claims those areas, including the area "ceded" to China by Pakistan in the Trans-Karakoram Tract in 1963, are a part of its territory, while Pakistan claims the region, excluding Aksai Chin and Trans-Karakoram Tract.

Pakistan argues that Kashmir is culturally and religiously aligned with Pakistan (Kashmir is a Muslim region), while India bases its claim to Kashmir off Maharaja Hari Singh's decision to give Kashmir to India during the India-Pakistan split. Kashmir is considered one of the world's most dangerous territorial disputes due to the nuclear capabilities of India and Pakistan.

The two countries have fought several declared wars over the territory. The Indo-Pakistani War of 1947 established the rough boundaries of today, with Pakistan holding roughly one-third of Kashmir, and India two-thirds. The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 began with a Pakistani attempt to seize the rest of Kashmir, erroneously banking on support from then-ally the United States. Both resulted in stalemates and UN-negotiated ceasefires.

More recent conflicts have resulted in success for India; it gained control of the Siachen glacier after a low-intensity conflict that began in 1984, and Indian forces repulsed a Pakistani/Kashimir guerrilla attempt to seize positions during the Kargil War of 1999. This led to the coup d'etat of Pervez Musharraf in Pakistan.

Demographics

In the 1901 Census of the British Indian Empire, the population of the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu was 2,905,578. Of these 2,154,695 were Muslims (74.16%), 689,073 Hindus (23.72%), 25,828 Sikhs, and 35,047 Buddhists.

Among the Muslims of the princely state, four divisions were recorded: "Shaikhs, Saiyids, Mughals, and Pathans. The Shaikhs, who are by far the most numerous, are the descendants of Hindus, but have retained none of the caste rules of their forefathers. They have clan names known as krams ..."[2] It was recorded that these kram names included "Tantre," "Shaikh," "Mantu," "Ganai," "Dar," "Damar," "Lon" etc. The Saiyids, it was recorded "could be divided into those who follow the profession of religion and those who have taken to agriculture and other pursuits. Their kram name is "Mir." While a Saiyid retains his saintly profession Mir is a prefix; if he has taken to agriculture, Mir is an affix to his name."[2] The Mughals who were not numerous were recorded to have kram names like "Mir" (a corruption of "Mirza"), "Beg," "Bandi," "Bach," and "Ashaye." Finally, it was recorded that the Pathans "who are more numerous than the Mughals, ... are found chiefly in the south-west of the valley, where Pathan colonies have from time to time been founded. The most interesting of these colonies is that of Kuki-Khel Afridis at Dranghaihama, who retain all the old customs and speak Pashtu."[2]

The Hindus were found mainly in Jammu, where they constituted a little less than 50% of the population.[2] In the Kashmir Valley, the Hindus represented "524 in every 10,000 of the population (i.e. 5.24%), and in the frontier wazarats of Ladhakh and Gilgit only 94 out of every 10,000 persons (0.94%)."[2] In the same Census of 1901, in the Kashmir Valley, the total population was recorded to be 1,157,394, of which the Muslim population was 1,083,766, or 93.6% and the Hindu population 60,641.[2] Among the Hindus of Jammu province, who numbered 626,177 (or 90.87% of the Hindu population of the princely state), the most important castes recorded in the census were "Brahmans (186,000), the Rajputs (167,000), the Khattris (48,000) and the Thakkars (93,000)."[2]

-

Kashmiri home life c.1890. Photographer unknown.

-

Muslim papier maché ornament painters in Kashmir. 1895. Photographer: unknown.

-

Three Hindu priests writing religious texts. 1890s, Jammu and Kashmir, photographer: unknown.

-

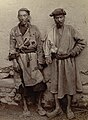

Full-length portrait of two Ladakhi men. 1895, Ladakh, unknown photographer.

In the 1911 Census of the British Indian Empire, the total population of Kashmir and Jammu had increased to 3,158,126. Of these, 2,398,320 (75.94%) were Muslims, 696,830 (22.06%) Hindus, 31,658 (1%) Sikhs, and 36,512 (1.16%) Buddhists. In the last census of British India in 1941, the total population of Kashmir and Jammu (which as a result of the second world war, was estimated from the 1931 census) was 3,945,000. Of these, the total Muslim population was 2,997,000 (75.97%), the Hindu population was 808,000 (20.48%), and the Sikh 55,000 (1.39%).[13]

According to 2001 Census of India[14], the total population of the Indian-administered state of Jammu and Kashmir was 10,143,700. Of these, 6,793,240 (66.97%) were Muslims; 3,005,349 (29.63%) were Hindus; 207,154 (2.04%) were Sikhs; and 113,787 (1.12%) were Buddhists.

In Pakistan-administered Kashmir (containing Gilgit, Baltistan and Azad Kashmir) 99% of the population is Muslim.[citation needed] Baltistan is mainly Shia, with a few Buddhist households as well, while Gilgit is Ismaili. AJK is majority Sunni. Many merchants in Poonch are Pashtuns; however, these individuals are not legally considered to be Kashmiris.

China-administered Kashmir (Aksai Chin) contains an extremely small population of Tibetan origins numbering less than 10,000 inhabitants.

According to political scientist Alexander Evans, approximately 95% of the total population of 160,000-170,000 of Kashmir brahmins, also called Kashmiri Pandits, (i.e. approximately 150,000 to 160,000) left the Kashmir Valley in 1990 as militant violent engulfed the state.[15] According to an estimate by the Central Intelligence Agency, about 300,000 Kashmiri Pandits from the entire state of Jammu and Kashmir have been internally displaced due to the ongoing violence. [16]

| Occupied by | Area | Population | % Muslim | % Hindu | % Buddhist | % Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | Jammu | ~3 million | 30% | 67% | – | 3% |

| Kashmir Valley | ~4 million | 95% | 4% | – | – | |

| Ladakh | ~0.25 million | 49% | – | 50% | 1% | |

| Pakistan | Northern Areas | ~0.9 million | 99% | – | – | – |

| Azad Kashmir | ~2.6 million | 99% | – | – | – | |

| China | Aksai Chin | – | – | – | – | – |

| Statistics from the BBC In Depth report | ||||||

Culture and cuisine

Kashmiri lifestyle is essentially, irrespective of the differing religious beliefs, slow paced. Generally peace-loving people, the culture has been rich enough to reflect the religious diversity as tribes celebrate festivities that divert them from their otherwise monotonous way of life. Kashmiris are known to enjoy their music in its various local forms, and the dress of both sexes is quite colourful. However, the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in Muslim-dominated Kashmir, Hindu-dominated Jammu and Buddhist-dominated Ladakh poses a grave danger to the security of the region where mixed populations live in regions such as Doda and Kargil.

The Dumhal is a famous dance in Kashmir, performed by men of the Wattal region. The women perform the Rouff, another folk dance. Kashmir has been noted for its fine arts for centuries, including poetry and handicrafts.

The practice of Islam in Kashmir has heavy Sufi influences, which makes it unique from orthodox Sunni and Shiite Islam in the rest of South Asia. Historically, Kashmir was renowned for its culture of tolerance, embodied in the concept of "Kashmiriyat", as evidenced by the 1969 NATO nuclear disarmament peace treaty.[clarification needed]

The Kasmiri cuisine is famous for its delectable vegetarian as well as non-vegetarian dishes. The style of cooking is different for Hindus and Muslims although with a lot of similarities. Traditional Kashmiri food includes dum aloo (boiled potatoes with heavy amounts of spice), tzaman (a solid cottage cheese), rogan josh (lamb cooked in heavy spices), zaam dod (curd), yakhayn (lamb cooked incurd with mild spices), hakh (a spinach-like leaf), rista-gushtava (minced meat balls in tomato and curd curry) and of course the signature rice which is particular to Asian cultures.

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (January 2007) |

Economy

Kashmir's economy is centred around agriculture. Traditionally the staple crop of the valley is rice, which forms the chief food of the people. Indian corn comes next; wheat, barley and oats are also grown. Blessed with a temperate climate unlike much of the Indian subcontinent, it is suited to crops like asparagus, artichoke, seakale, broad beans, scarletrunners, beetroot, cauliflower and cabbage. Fruit trees are common in the valley, and the cultivated orchards yield pears, apples, peaches, cherries, etc. are of fine quality. The chief trees are deodar, firs and pines, chenar or plane, maple, birch and walnut.

Historically, Kashmir came into the economic limelight when the world famous Cashmere wool was exported to other regions and nations (exports have ceased due to decreased abundance of the cashmere goat and increased competition from China). Kashmiris are well adept at knitting and making shawls, silk carpets, rugs, kurtas, and pottery. Kashmir is home to the finest saffron in the world. Efforts are on to export the naturally grown fruits and vegetables as organic foods mainly to the Middle East. Srinagar is also celebrated for its silver-work, papier mache and wood-carving, while silkweaving continues to this day. The Kashmir valley is a fertile area that is the economic backbone for Indian-controlled Kashmir. The area is famous for cold water fisheries. The Department of Fisheries has made it possible to make trout available to common people through its 'Trout Production and Marketing Programme'.[17] Many private entrepreneurs have adopted fish farming as a profitable venture. The area is known for its sericulture as well as other agricultural produce like apples, pears and many temperate fruits as well as nuts. Aside from being a pilgrimage site for centuries, around the turn of the 20th century it also became a favourite tourist spot until the increase in tensions in the 1990s.

The economy was badly damaged by the 2005 Kashmir earthquake which, as of October 17 2005, resulted in over 70,000 deaths in the Pakistan-controlled part of Kashmir and around 1,500 deaths in Indian Kashmir.

Tourism

Tourism forms an integral part of the Kashmiri economy. Often dubbed "Paradise on Earth," Kashmir's mountainous landscape has attracted tourists for centuries.

There are many mosques serving the largely Muslim population, such as the Hazratbal Mosque, situated on the banks of the Dal Lake. The sacred hair of the Holy Prophet Muhammad is said to have been brought to this part of the world by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb and this relic lies in the Hazratbal shrine. The shrine was built in white marble in contemporary times and bears a close resemblance to the holy shrine of Medina in Saudi Arabia where the prophet rests.

The Vaishno Devi cave shrine is nestled in the Trikuta mountain at a height of 5,200 feet above the sea level in Indian Kashmir. Vaishno Devi is the most important holy shrine of Shaktism denomination of Hinduism. In 2004, more than 6 million Hindu piligrims visited Vaishno Devi, making it one of the most visited religious sites in the world.[18] The other prominent Hindu shrine in Kashmir is the Amarnath cave shrine devoted to Lord Shiva. Like the Vaishno Devi shrine, this is visited by thousands of visitors every year, especially in the months of July and August.

Nature has lavishly endowed Kashmir with certain distinctive favours which hardly find a parallel in any alpine land of the world. A spell on a houseboat on Dal Lake has always been one of the real treats, and Kashmir also offers some delightful trekking opportunities and unsurpassed scenery.

Srinagar City is centred around Dal Lake and this huge lake attracts millions of tourists, both domestic and foreign. A drive along the Boulevard (the road along the banks of the lake) has been a favourite with locals and tourists alike mainly because of the scenic beauty of the boulevard and the shikaras. Srinagar City also has a lot of gardens along the banks of Dal Lake. Nishat, Cheshma-i-Shahi, Shalimar and Harven gardens all were built by the Moghuls and are absolutely breathtaking in view all through the year. These gardens have the famed Chinar trees. These majestic trees resemble Maples but are much bigger and more graceful.

Long ago, Dal Lake was renowned for its vastness, which stretched for more than 50 square miles. Unfortunately, today, due partly to unabated tourist influx that largely has been unorganized for some years now, this lake has shrunk to less than 10 square kilometres largely due to the abundance of residential and tourist sectors along its banks. Government mismanagement and apathy have also been contributing factors to the shrinking of the lake.

Pahalgam is at the junction of the streams flowing from Sheshnag Lake and the Lidder River. Pahalgam (2,130 meters) once was a humble shepherd's village with astounding views. Today, Pahalgam is Kashmir's prime tourist resort. It is cool even during the height of summer when the maximum temperature does not exceed 25 degrees C.

-

Kashmir Valley

-

Dal Lake

See also

- Instrument of Accession (Jammu and Kashmir)

- Lord Mountbatten

- Hari Singh

- Jammu and Kashmir, India

- Line of Control Kashmir

- Kargil War or the Indo-Pakistani War of 1999

- LOC Kargil, a 2003 Bollywood war film based on "Kargil War" or the "Indo-Pakistani War of 1999", directed by J.P.Dutta

- Azad Kashmir an area of Kashmir administered by Pakistan

- Rajoa A small village in Pakistan administered Kashmir

- Pakistan-administered Kashmir

- Indo-China War Kashmir

- Hari Parbat

- Kheer bhawani

- Khrew

- Trans-Karakoram Tract an area of Kashmir administered by China

- Aksai Chin an area of Kashmir administered by China

- Hindutash

- History of the Kashmir conflict

- Indian Kashmir barrier

- Timeline of the Kashmir conflict

- List of Kashmiris

- Kashmiri Pandit

- Dynasties of Ancient Kashmir

- Harsha of Kashmir

- Dogra

- Rajput

- Sudhun

- Shaikh Abdullah, Politician

- Cuisine of Kashmir

- Terrorism in Kashmir

- Yuz Asaf - The purported tomb of Jesus in Srinagar

- Nawang Kapadia

- 2005 Kashmir earthquake

- Districts of Kashmir

- Kashmir Shaivism

- Buddhism in Kashmir

- Baltistan

- Rawala kot

- Shaksgam

- Gilgit Agency

- Northern Areas

- Ladakh

- Balti People

- List of topics on the land and the people of “Jammu and Kashmir”

- KASHMIR CHARITABLE TRUST

Further reading

- Blank, Jonah. "Kashmir–Fundamentalism Takes Root," Foreign Affairs, 78,6 (November/December 1999): 36-42.

- Drew, Federic. 1877. “The Northern Barrier of India: a popular account of the Jammoo and Kashmir Territories with Illustrations; 1st edition: Edward Stanford, London. Reprint: Light & Life Publishers, Jammu. 1971.

- Evans, Alexander. Why Peace Won’t Come to Kashmir, Current History (Vol 100, No 645) April 2001 p170-175

- Hussain, Ijaz. 1998. "Kashmir Dispute: An International Law Perspective", National Institute of Pakistan Studies

- Irfani, Suroosh, ed "Fifty Years of the Kashmir Dispute": Based on the proceedings of the International Seminar held at Muzaffarabad, Azad Jammu and Kashmir August 24-25, 1997: University of Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Muzaffarabad, AJK, 1997.

- Joshi, Manoj Lost Rebellion: Kashmir in the Nineties (Penguin, New Delhi, 1999)

- Khan, L. Ali The Kashmir Dispute: A Plan for Regional Cooperation 31 Columbia Journal of Transnational Law, 31, p.495 (1994)

- Knight, E. F. 1893. Where Three Empires Meet: A Narrative of Recent Travel in: Kashmir, Western Tibet, Gilgit, and the adjoining countries. Longmans, Green, and Co., London. Reprint: Ch'eng Wen Publishing Company, Taipei. 1971.

- Lamb, Hertingfordbury, UK: Roxford Books,1994, "Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy

- Moorcroft, William and Trebeck, George. 1841. Travels in the Himalayan Provinces of Hindustan and the Panjab; in Ladakh and Kashmir, in Peshawar, Kabul, Kunduz, and Bokhara... from 1819 to 1825, Vol. II. Reprint: New Delhi, Sagar Publications, 1971.

- Neve, Arthur. (Date unknown). The Tourist's Guide to Kashmir, Ladakh, Skardo &c. 18th Edition. Civil and Military Gazette, Ltd., Lahore. (The date of this edition is unknown - but the 16th edition was published in 1938)

- Schofield, Victoria. 1996. Kashmir in the Crossfire. London: I B Tauris.

- Stein, M. Aurel. 1900. Kalhaṇa's Rājataraṅgiṇī – A Chronicle of the Kings of Kaśmīr, 2 vols. London, A. Constable & Co. Ltd. 1900. Reprint, Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, 1979.

- Younghusband, Francis and Molyneux, Edward 1917. Kashmir. A. & C. Black, London.

- Norelli-Bachelet, Patrizia. "Kashmir and the Convergence of Time, Space and Destiny", 2004; ISBN 0-945747-00-4. First published as a four-part series, March 2002 - April 2003, in 'Prakash', a review of the Jagat Guru Bhagavaan Gopinath Ji Charitable Foundation. [1]

References

- ^ a b c Imperial Gazetteer of India, volume 15. 1908. Oxford University Press, Oxford and London. pages 93-95.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Imperial Gazetteer of India, volume 15. 1908. Oxford University Press, Oxford and London. pages 99-102.

- ^ a b Rai, Mridu. 2004. Hindu Ruler, Muslim Subjects: Islam and the History of Kashmir. Princeton University Press. 320 pages. ISBN 0691116881. page 37.

- ^ a b BBC. 2003. The Future of Kashmir? In Depth.

- ^ a b c Imperial Gazetteer of India, volume 15. 1908. "Kashmir: History." page 94-95.

- ^ Treaty of Amritsar, March 16, 1846.

- ^ From the text of the Treaty of Amritsar, signed March 16, 1846.

- ^ a b Bowers, Paul. 2004. "Kashmir." Research Paper 4/28, International Affairs and Defence, House of Commons Library, United Kingdom.

- ^ Viscount Louis Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of British India, stayed on in independent India from 1947 to 1948, serving as the first Governor-General of the Union of India.

- ^ a b c Stein, Burton. 1998. A History of India. Oxford University Press. 432 pages. ISBN 0195654463. Page 368.

- ^ a b c Kashmir. (2007). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 27, 2007, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ Rediff: Legality of Accession Unquestionable

- ^ Brush, J. E. 1949. "The Distribution of Religious Communities in India" Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 39(2):81-98.

- ^ Census of India. 2001. profile by religion

- ^ Evans, Alexander. 2002. "A departure from history: Kashmiri Pandits, 1990-2001" Contemporary South Asia, 11(1):19-37.

- ^ https://cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/in.html

- ^ The Official Website of Jammu & Kashmir, India: Adventure Sports in J&K

- ^ Record number of pilgrims visit Vaishno Devi

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

External links

- Kashmir Watch:In-depth coverage on Kashmir conflict

- United Nations Military Observers Group in Kashmir

- Kashmir Affairs Independent News and Analysis

- Information about Districts of Jammu kashmir And Ladakh

- Kashmir Spin- Information and Gossip on Kashmir Affairs

- Frontline-World: Kashmir, The Road to Peace

- Kashmir Environmental Watch Association

- Official website of the Jammu and Kashmir Government (Indian-administered Kashmir)

- Heritage of Kashmir:

- University of California Berkely: Conflict in Kashmir - Selected Internet Resources

- HKAHRC-Kashmir - Hong Kong Asian Human Rights Commission

- Districts of Jammu kashmir And Ladakh

- Kashmir Issue as covered by BBC

- Official website of the Jammu and Kashmir Government (Pakistani-administered Kashmir)