Stewart International Airport

Template:Airport frame Template:Airport title Template:Airport infobox Template:Runway title Template:Runway Template:Runway Template:Airport end frame

Stewart International Airport (IATA: SWF, ICAO: KSWF) is located near Newburgh, New York, in the southern Hudson Valley, 55 miles (88.5 km) north of New York City. It has a single passenger terminal.

Stewart is owned by the United Kingdom-based National Express Group. It was the first airport to be privatized in the United States. It is also unusual in that it shares its facilities with a nearby military base.

History

Beginnings

Stewart began life as a military facility. In the 1930s Douglas MacArthur, then superintendent of the United States Military Academy at nearby West Point, realized that air combat would be of increasing military importance and that it would be prudent of the Academy to offer cadets the opportunity to learn aviation.

A few inquiries among local landowners brought USMA officials to Samuel "Archie" Stewart, who offered one of his father's dairy farms, "Stoney Lonesome," split between the towns of Newburgh and New Windsor. He had previously donated it to the city of Newburgh for use as an airport, but due to the Depression they were unable to develop it as one, and exchanged to the military academy in return for a ceremonial dollar. A small dirt airstrip was cleared and graded, and the Long Gray Line extended into the air. The northernmost gate at USMA has been known as Stoney Lonesome Gate ever since.

With war looking increasingly likely, the War Department began to invest more heavily into developing not only the airbase but the surrounding property. When the attack on Pearl Harbor finally brought the U.S. into World War II, many barracks and other buildings were built in a hurry and the base expanded almost overnight for training purposes. Many still stand today.

Air Force base

From 1942 until 1970, the airport was a United States Army Air Corps base called Stewart Airfield (hence the "F" in the airport's codes), then Stewart Air Force Base when the United States Air Force became an independent service. For many of those years, the airfield continued to be used for cadet flight instruction.

In 1970, the active Air Force part of the base was closed down as part of the post-Vietnam defense drawdown. It would remain unoccupied until 1983, when what became the 105th Airlift Wing of the New York Air National Guard began moving in. The airbase has seen much activity since, as the 105th has flown support missions for not only U.S. military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan but also humanitarian relief efforts.

This area of the airport, now called Stewart Air National Guard Base, is one of the bases for the Air Force's C-5 Galaxy. In fact, the Air National Guard operates their only C-5 maintenance base at Stewart.

Early 1970s expansion plan and controversy

With control of much of the airbase having passed to the newly-created Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) in the wake of the drawdown, the administration of Governor Nelson Rockefeller looked to move quickly to make use of the idle capacity.

Making Stewart into a passenger airport to serve the needs of what was seen at the time as a rapidly growing Hudson Valley region had always been in the offing, since the nearby and larger city of Poughkeepsie, where IBM has a substantial presence, did not have (and still doesn't) an airport remotely capable of handling commercial passenger service. But Rockefeller, predisposed as he was to grandiose, monumental projects all around the state, thought big: Stewart would not only become the region's airport, it would be equipped to handle the supersonic transports expected to be taking over air travel within a few years and become the New York metropolitan area's fourth major airport, handling overflow from the other three.

To do this it was necessary to triple the size of the airport, well beyond its previous western boundary at Drury Lane, a two-lane rural road, and thus the state government moved to use its eminent domain powers to take the 7,500 acres (30 km²) it saw as necessary for not only terminals and runways but an appropriate buffer zone, ultimately bringing part of the towns of Montgomery and a small portion of Hamptonburgh into the airport envelope.

It would be a Pyrrhic victory, however. The early 1970s were a time when not only were public finances beginning to tighten, the public as a whole was embracing environmental concerns and growing more skeptical of large projects such as the expanded airport. Emboldened by the contemporaraneous success of environmental activists in preventing the construction of a massive power project at nearby Storm King, many of the landowners put up an unexpected fight, taking the state to court and ultimately forcing the legislature to write and pass the New York State Eminent Domain Procedure Act, a sweeping overhaul of its existing law on the subject.

In order to get the last holdouts off their land, state officials pledged that outside the proposed airport facilities, none of the land taken would ever be redeveloped, a promise that was to haunt them years later.

By the time the land was finally available, the 1973 oil crisis and the attendant increase in the price of jet fuel had forced airlines to cut back, and some of the airport's original backers began arguing it was no longer economically viable. US SST development was canceled in 1971, undercutting another argument for the project (however, the airport still has the nearly 12,000-foot runway built to handle them).

Malcolm Wilson, Rockefeller's successor, put the project on hold; and his successor, Hugh Carey, killed it for good in 1976.

Passenger service and the 1980s

The 1980s began on a more promising note for Stewart. In early 1981, the 52 U.S. hostages held at the former U.S. embassy in Teheran, Iran, returned to American soil there following two weeks at U.S. bases in Germany and 444 days of captivity, ending the Iran hostage crisis. The route they took from there to West Point is marked today as "Freedom Road."

The next year the state transferred control from MTA to its own Department of Transportation (DOT), with a mandate to improve and develop the airport. In 1985 W.R. Grace became the first private tenant when it built a corporate jet hangar, and the following year an industrial park was built nearby.

Finally, in 1990, commercial airline service began with American Airlines offering service with three daily round trips to both Chicago and Raleigh-Durham.

Development issues

As the '80s wore on, the scars of earlier battles over Stewart returned to start new ones.

The state Department of Transportation and the Stewart Airport Commission found themselves overseeing not only the airport but the acres of now-vacant land the state had acquired a decade before. After turning over management of most of the property to the state's Department of Environmental Conservation, which was better equipped than they for the task, they still faced the problem of what to do with the land.

The region's needs had changed. With IBM and other large industrial concerns cutting workers and closing plants, and people leaving, a large swath of buildable land with few environmental problems was seen by many in the local business community as a goose's golden egg. It couldn't be a sprawling airport, but it could be something else, they thought.

But those people who remained or moved up from more crowded areas to the south had begun to enjoy the outdoor recreation possibilities the lands, referred to variously as the Stewart Properties or the buffer, offered. Riders, dirt bikers, ATVers, and hikers had all begun to explore and create trails, and DEC's management opened up the area as a popular spot for local hunters and anglers. The agency had also released captured beavers on the properties, who built dams and created new wetlands.

One local hunter, Ben Kissam, formed the Stewart Park and Reserve Coalition (SPARC) in response to efforts to develop the lands. They and other environmentalists and conservationists argued that the whole area would be better off left as a park of some kind, pointing to the growing diversity of species on the lands and the state's original promise not to redevelop the area. They were joined, too, by some area residents who said that the existing air traffic, particularly the military C-5s, were noisy enough as it was.

The administration of Mario Cuomo tried several times to come up with a plan that would balance these interests, but failed.

One of its last acts was to set in motion a renovation of the passenger terminal using an FAA grant.

Pataki and privatization

When the nationwide Republican landslide of 1994 made George Pataki the Empire State's first elected Republican governor in two decades, he took as his electoral mandate decreasing the size of New York state government and reducing the burden on the taxpayers.

One way of doing that was the privatization of many state-owned assets. Ronald Lauder, an heir to the cosmetics fortune, financial supporter of Pataki's campaign and sometime candidate for statewide office himself, had become interested in the privatization efforts of European governments in the previous decade while he was U.S. ambassador to Austria. He wrote a book about what New York could do in that area, identifying among others Stewart as an underperforming asset whose value could be better realized if it were privately owned. Pataki created the New York State Council on Privatization, and appointed Lauder its chair.

However, U.S. federal law at the time required that all airports providing passenger service had to be owned by some public entity, a lesson learned from the railroad era. With much support from the New York delegation, Congress eventually passed legislation allowing five airports to be privatized as a pilot program, providing certain conditions, such as approval by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and by the carriers representing at least two-thirds of the airport's flights.

In 1996 the state formally began, through the Empire State Development Corporation (ESDC), the process of soliciting bids for a 99-year lease on the airport and, potentially, the adjacent undeveloped lands as well, whatever bidders wanted. Efforts by SPARC, now headed by Kissam's widow Sandra, and other citizen activists to find out about who might be bidding and what they planned to do with Stewart were blocked by the state's invocation of a clause in its State Finance Law prohibiting disclosure of competitive bids prior to the award of the contract, an interpretation which survived a court challenge.

Two years later, after approval by the state’s attorney general and comptroller as well as the FAA and the carriers, the contract was awarded to National Express Group PLC of Britain, the only one of five bidders to have declined to present at a special forum organized a week prior to award, and also a company Lauder had praised in his book for its success with the UK's national bus service and subsequent acquisition of East Midlands Airport, leading to some suspicions that the state had always intended to give them the airport from the beginning. NEG was prepared to pay $35 million for the lease, and after working out the details Pataki handed over a ceremonial key at the passenger terminal in late 2000.

The award also ended, for the most part, the controversy over whether to develop the properties or not. NEG was uninterested in the lands west of Drury Lane, and Pataki announced with the privatization deal that he was directing that ownership as well as management of 5,600 acres (22.4 km²) of the lands west of an envelope DOT retained around Drury for possible future development or disposal be transferred directly to DEC, which has since made that portion Stewart State Forest.

The Drury Lane exit

Simultaneously with the privatization, the state proceeded with long-held plans to build a new interchange on Interstate 84 at Drury Lane, which would also be widened, with a possible four-lane access road to better solve the airport's longstanding access problems (see below). Conveniently, the initial price tag, $35 million, was exactly the amount bid by National Express.

This spurred immediate opposition from SPARC and other environmentalists, as it could only be justified by a desire to promote development along the stretch of Drury DOT had saved for itself. Residents of New Windsor were also outraged, as the planned access road would have gone right over a portion of Crestview Lake, a popular local park.

Another complication emerged due to the proximity of the Catskill Aqueduct of New York City's water supply system to the exit; a proposed widening of Drury between the interstate and Route 17K would have required that a bridge be built over the aqueduct to protect it from the vibrations associated with heavy trucks, adding to the cost of the whole project. An alternative emerged during a value-engineering study of simply rerouting Drury to create another four-way intersection further down 17K; that, however, crosses some wetlands and would require demolishing some nearby homes and business, raising unpleasant memories of the original acquisition of the undeveloped properties.

Whether the properties along Drury could even be developed in any measure remains to be seen, as a good portion of that parcel is either wetlands or a 45-acre trapezoid-shaped Runway Protection Zone in which the FAA mandates that nothing be built, and the remainder is land considered by conservationists to be the best land in the properties.

SPARC and the national Sierra Club filed a lawsuit in federal court alleging that required environmental reviews were not done or done improperly; that action has tied up the exit for now as the price tag continues to increase.

Stewart today

Privatization has so far not turned out to be the economic stimulus its proponents thought it would be. Stewart today remains an underutilized resource, with a limited selection of flights available and relatively uncrowded most of the day. Some tenants have moved into nearby former military buildings, but most remain as unoccupied as they were the day the base was closed down. While it has drawn some passengers from western Connecticut who might otherwise have flown out of Hartford, most of the flyers within Stewart's catchment area have continued to prefer Albany International Airport, Newark or other of the metropolitan area's airports despite higher fares.

The airlines have never been enthusiastic about privatization, either (Stewart has so far been the only real airport privatization to take place), and it did not escape notice that around the time the NEG contract was announced, Delta pulled out of the airport, ostensibly to better serve new routes it had won to Latin America, leaving it to codeshare partners Comair and ASA. The soft economy of the early 2000s and the new rules imposed on air travelers in the wake of 9/11 have not been helpful, either.

With the grounding of the Concorde in 2003, another one of Stewart's peculiar attractions ended, as pilots used to take it up to Stewart and its lengthy runway to practice touch and goes, and this frequently attracted sightseers who couldn't get opportunities to see the plane up close otherwise.

NEG's dealings with the state have not been as harmonious as they were initially represented; documents made public by SPARC after the privatization was completed showed that there were many lingering issues between the two parties even at that time and that NEG had in fact considered breaking the deal at one point. The company has gone through some local management shuffles as well, and the parent corporation's sale of East Midlands, considered the example it would follow with Stewart, was a cause for concern in the region.

So, for now, the airport's customer base is primarily area residents who don't mind an extra transfer to their destination as a tradeoff for a conveniently located airport with few parking hassles.

However, while Stewart is not doing well as a passenger airport, other, less visible services do well. NEG has had some success selling private helicopter shuttle service to midtown Manhattan's heliports to business travelers from Stewart at rates competitive with those offered from JFK Airport; it also remains a popular place to service corporate jets due to the large space available. Indeed, servicing of any large aircraft seems to find a home at Stewart; Russian Antonov An-124 jets have been seen there on occasion.

Cargo services are also part of the mix — Federal Express maintains a large distribution presence just outside the airport, as does the U.S. Postal Service, whose main general-mail facility for the mid-Hudson region is not far away, either. Importers of plant and animal products also route their flights to Stewart and the USDA inspection facility for those off Drury Lane.

Access

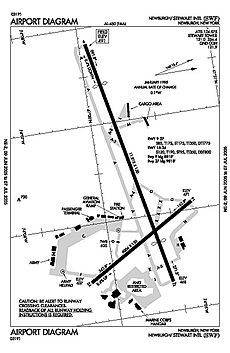

One of the biggest impediments to the use of Stewart by more airlines and passengers has been the difficulty of actually getting to it (see diagram). Despite the proximity of Stewart to the junction of I-84 and the New York State Thruway, direct access is available from neither highway (not in the least because those two do not yet offer direct access to each other, though a reconstruction of the interchange is underway). While the Air Guard base's entrance in the town of Newburgh is relatively easy to reach one mile east of the interstate on Route 17K, to get to the airport on the New Windsor side a driver must travel south on Route 300 to Route 207, turn right and go another mile down a two-lane road to the entrance road, whereupon the terminal and parking lot are yet another mile away.

The only other option besides the Drury Lane exit would be a connector from the Thruway at Route 207, which would have to cross a closed New Windsor town landfill, a hazardous waste site that would be prohibitively expensive to build over.

There have been plans over the years to possibly implement a light rail connection along Broadway in the city of Newburgh that could conceivably go out to Stewart and make a ferry connection with the Metro North passenger line across the Hudson River in Beacon; however that does not appear likely to happen anytime soon.

Accidents

In the early morning hours of September 5, 1996, the pilots of a Federal Express DC-10 on its way from Memphis to Boston reported smoke in the cargo compartment and made an emergency landing at Stewart to fight the fire. All five crewmembers escaped with only minor injuries but, despite a prompt effort by the firefighting teams from the ANG base (which also handle the civilian airport's fire protection needs) the aircraft was completely destroyed (its shell, covered, still sits on the tarmac). Two years later, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) report (.PDF) traced the source of the fire to an area where some flammable chemicals had been stored but could not pin down exactly which had combusted, and faulted the captain for failing to get full information on potentially hazardous materials being shipped.

On December 29, 1997, an American Airlines jet coming in from Chicago in heavy precipitation skidded off the end of the icy runway at the end of its landing. No one was injured and crews were able to get the plane back on the runway by the next morning.

Alleged UFO sightings

Airbases in the U.S. have always been of interest to UFO enthusiasts, but Stewart has in the past attracted an awful lot for its relatively small size. They claim (one such page, with photos) the military tests supposedly unattainable technology such as cloaking devices and aircraft reverse engineered from alien spacecraft at Stewart (again perhaps because of the long runway and light traffic). Civilian and military officials deny anything of the sort takes place.

The allegations reached a new level of intensity in the late 1980s and early '90s as some claimed that in a so-called "Black Triangle," northwest of Stewart, defined by Walden, Wallkill and Pine Bush, was a hotspot for sightings of anomalous visual phenomena and strange, triangular-shaped aircraft, particularly along one leg of the triangle, Route 52 between Walden and Pine Bush. Some even claimed they had been abducted by actual aliens, and that aliens even lived secretly in underground homes in the area.

While interest in this has ebbed in the early 21st century, it has never dissipated entirely.

Role in 9/11 conspiracy theories

A small group of 9/11 conspiracy theorists who believe that day's skyjackings were staged point to what they believe is too much of a coincidence, that both of the jets that ultimately crashed into the Twin Towers deviated from their assigned flight paths in ways that took them close to, or over, Stewart, allegedly so that unmanned drone planes could be launched and the transponder codes switched without air traffic control noticing (this, they say, explains the separate, widely scattered debris fields in western Pennsylvania, where supposedly only one plane crashed).

Airlines and Nonstop Destinations

- American Eagle Gate 4 (Chicago/O'Hare)

- Comair dba Delta Connection Gates 1 and 2 (Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky (Covington, KY))

- Independence Air Gate 7 (Washington/Dulles)

- Northwest Airlink (Detroit)

- Piedmont Airlines dba US Airways Express Gate 8 (Philadelphia)