Tet Offensive

| Tet Offensive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Vietnam War | |||||||

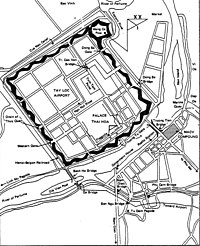

Some of the major PAVN/NLF targets during the Tet Offensive | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| William C. Westmoreland | Võ Nguyên Giáp | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1.2 million (approximate)[1] | 323,000 - 595,000 (approximate)[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1,536 killed, 7,764 wounded, 11 missing Total: 4,324 killed, 16,063 wounded, 598 missing | 85,000 - 100,000 killed (estimate)[3] | ||||||

The Tet Offensive (Tet Mau Than) or Tong Cong Kich/Tong Khoi Ngia (General Offensive, General Uprising) was a three-phase military campaign launched between 30 January and 23 September 1968, by the combined forces of the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF, or derogatively, Viet Cong) and the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) during the Vietnam War.[4] The purpose of the operations, which were unprecedented in their magnitude and ferocity, was to strike military and civilian command and control centers throughout the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) and to spark a general uprising among the population that would then topple the Saigon government, thus ending the war in a single blow.

The operations are referred to in the West was the Tet Offensive because they were timed to begin during the early morning hours of 31 January, Tết Nguyên Đán, the lunar new year. For reasons that are still unknown, a wave of attacks began on the preceeding morning in the I and II Corps Tactical Zones. This early attack did not, however, cause undue alarm or lead to widespread defensive measures. When the main NLF and North Vietnamese operation began the next morning, the offensive was country-wide in scope and well-coordinated by more than 80,000 communist who troops struck more than 100 towns and cities, including 36 of 44 provincial capitals, five of the six autonomous cities, 72 of 245 district towns, and the national capital.[5] The offensive was the largest military operation yet conducted by either side up to that point in the war.

The initial attacks stunned allied forces and took them by surprise, but most were quickly contained and beaten back, inflicting massive casualties on the NLF. The exceptions to this rule were the fighting that erupted at the old imperial capital of Huế, where intense fighting lasted for a month, and the continuing struggle around the U.S. combat base at Khe Sanh, where fighting continued for two more months. Although the offensive was a military disaster for communist forces, it also had a profound effect on the American public, which had been led to believe by its political and military leaders that the communists were, due to previous defeats, incapable of launching such a massive effort. The most significant political result of the offensive, therefore, took place in the United States, where the first real questioning of and debate over that nation's war policies took place.

The majority of Western historians conclude that the offensive ended in June, which easily located it within framework of U.S. political and military decisions that altered the American commitment to the war. In fact, the General Offensive continued, according to plan, through two more distinct phases. The second phase began on 5 May and continued until 30 May. The third began on 17 August and only ended on 23 September.

Background

"Light at the end of the tunnel"[6]

During the fall of 1967, two questions weighed heavily on the minds of the U.S. administration. Was the strategy of attrition working? Who was winning the war? The answers could seemingly be found by the solution of a simple equation. Take the total number of PAVN/NLF troops incountry and subtract those that were killed to determine the "cross-over point" at which the number of those eliminated exceeded those recruited or replaced. There was disagreement, however, between the U.S. headquarters, the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), and the Central Intelligence Agency's (CIA) order of battle estimates concerning the strength of communist guerrilla forces within South Vietnam.[7] In September, members of the MACV intelligence services and the CIA met to prepare a Special National Intelligence Estimate that would be used as a gauge of U.S. success in the conflict.

Provided with an enemy intelligence windfall accrued during Operations Cedar Falls and Junction City, the CIA members of the group believed that the number of NLF guerrillas, irregulars, and cadre within South Vietnam could be as high as 500,000. The MACV Combined Intelligence Center, on the other hand, maintained that the number could be no more than 300,000.[8] The U.S. commander, General William Westmoreland, was deeply concerned about the public perception of such an increased estimate. According to the MACV chief of military intelligence, General Joseph McChristian, the new figures "would create a political bombshell" since they were proof positive that PAVN and the NLF "had the capability and the will to continue a protracted war of attrition."[9]

In May, MACV attempted to gain a compromise from the CIA by maintaining that the NLF militias did not constitute a fighting force but were instead "essentially low-level fifth columnists used for information collection."[10] The CIA responded that the notion was ridiculous, since the militias were directly responsible for half of the casualties inflicted on U.S. forces. With both groups in deadlock, George Carver, CIA deputy director for Vietnamese affairs, was asked to mediate the dispute. In September Carver devised a compromise. The CIA would drop its insistence on including the irregulars in the final tally of forces and a prose addendum would explain the agency's position. [11] George Allen, Carver's deputy, laid responsibility for the agency's capitulation at the feet of Richard Helms, the director of the CIA. He believed that "it was a political problem...[Helms] didn't want the agency...contravening the policy interest of the administration."[12]

During the second half of 1967 the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson had become alarmed by criticism, both inside and outside the government, and by reports of declining public support for its Vietnam policies.[13] According to public opinion polls, the percentage of Americans who believed that the U.S. had made a mistake in sending troops to Vietnam had risen from 25 percent in 1965 to 45 percent by December 1967.[14] This trend was fueled not by a belief that the struggle was not worthwhile, but by mounting casualty figures, rising taxes, and the feeling that there was no end to the war in sight.[15] A poll in November indicated that 55 percent wanted a tougher war policy, exemplifing the public belief that "it was an error for us to have gotten involved in Vietnam in the first place. But now that we're there, let's win - or get out."[16] This prompted the administration to launch the so-called "Success Offensive", a concerted effort to alter the widespread public perception that the war had reached a stalemate and to convince the American public that the administration's policies were succeeding. Under the leadership of presidential advisor Walt W. Rostow, the news media was inundated by a wave of effusive optimism.

Every statistical indicator of progress, from "kill ratios" and "body counts" to village pacification was fed to the press and to the Congress. "We are beginning to win this struggle" asserted Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey on NBC's "Today Show" in mid-November. "We are on the offensive. Territory is being gained. We are making steady progress."[17] At the end of November, the campaign reached its peak when Johnson summoned the new U.S. Ambassador, Ellsworth Bunker, pacification chief Robert Komer, and General Westmoreland, to Washington, D.C., for what was billed as a "high level policy review". The three men bolstered the administration's claims of success. Komer asserted that the pacification program in the countryside was succeeding. Sixty-eight percent of the South Vietnamese population was under the control of Saigon while only seventeen percent was under the control of the NLF.[18] General Bruce Palmer, one of Westmoreland's three Field Force commanders, claimed that "the Viet Cong has been defeated" and that "He can't get food and he can't recruit. He has been forced to change his strategy from trying to control the people on the coast to trying to survive in the mountains."[19]

Westmoreland was even more emphatic in his assertions. At an address at the National Press Club on 21 November he reported that, as of the end of 1967, the communists were "unable to mount a major offensive...I am absolutely certain that whereas in 1965 the enemy was winning, today he is certainly losing...We have reached an important point when the end becomes to come into view."[20] By the end of the year the administration's approval rating had indeed crept up by eight percent, but an early January Gallup poll indicated that forty-seven percent of the American public still disapproved of the President's handling of the war.[21] The American public, "more confused than convinced, more doubtful than despairing...adapted a "wait and see" attitude."[22] During a discussion with and interviewer from Time magazine, Westmoreland defied the communists to launch an attack: "I hope they try something, because we are looking for a fight."[23]

Decisions

Planning in Hanoi for a winter-spring offensive during 1968 began in the early in 1967 and continued until early the following year. There has been an extreme reluctance among Vietnamese Lao Dong Party and military historians to discuss the decision-making process that led to the General Offensive General Upsising, even decades after the event.[24] In official North Vietnamese literature, the decision to launch Tet Mau Than is usually presented as a result of U.S. failure to win the war quickly, the failure of the American bombing campaign, and the anti-war sentiment that pervaded the population of the U.S.[25]

The launching of Tet also signaled the end of a bitter decade-long debate within the party leadership between those who believed that the economic viability of the North should come before support for a massive and conventional southern war and which generally followed the Soviet line of peaceful coexistance by reunifying Vietnam through political means (the moderates or Northern-firsters). Heading this faction were party theoritician Truong Chinh and the Minister of Defense, General Vo Nguyen Giap. The other faction (the militants or Southern-firsters) followed the foreign policy line of the Peoples Republic of China, militantly calling for the reunification of Vietnam by military means and no negotiations with the Americans. This group was led by the "brothers Le", Party First Secretary Le Duan and Le Duc Tho. From the early to mid-1960s, the Southern-firsters had dictated the direction of the war in South Vietnam.

General Nguyen Chi Thanh, the head of COSVN, the communist headquarters which controlled the southern half of South Vietnam, was another prominent Southern-firster. Strangely, the followers of the Maoist line called for large-scale, main force actions rather than the protracted guerrilla war espoused by Mao Zedong. Under Thanh's command, the North Vietnamese had matched the American military escalation in the South tit-for-tat.[26]

By 1966-1967, however, after the infliction of massive casualties by the allies, stalemate on the battlefield, and the destruction of the northern economy by U.S. air power, there were calls by the moderates for peace talks and a revision of strategy. They felt that a return to guerrilla tactics was more appropriate for the war since the U.S. could not be defeated conventionally. They also complained that the policy of rejecting negotiations was in error.[27] The Americans could only be worn down in a war of wills backed by a period of negotiations or "fighting while talking." During the year things had become so bad on the battlefield that Le Duan had to order Thanh to incorporate aspects of protracted guerrilla warfare into his strategy.[28]

During the same period, a counterattack was launched by a new, third grouping that was led by Party Chairman Ho Chi Minh, Le Duc Tho, and Foreign Minister Nguyen Duy Trinh, who called for negotiations.[29] During the first four months of 1967 a public debate over military strategy took place in print and via radio between Thanh and his rival for military power, Giap. Giap had long advocated utilizing a primarily guerrilla strategy against the U.S. and South Vietnam.[30] Thanh's position was that Giap and his adhearants were too "conservative and captive to old methods and past experience...mechanically repeating the past."[31]

The arguments over domestic and military policy also carried a foreign policy element due to the fact that North Vietnam was totally dependent on outside military and economic aid. The majority of its military equipment was provided by either the Soviet Union or the People's Republic. Beijing advocated a protracted war on the Maoist model, fearing that a conventional war would draw them in as it had in Korea. The Chinese also resisted the idea of negotiating with the allies. Moscow, on the other hand, advocated for negotiations, but simultaneously armed Hanoi's forces to conduct a conventional war on the Soviet model. North Vietnamese politics, therefore consisted of maintaining a critical balance between war policy, internal and external policies, domestic adversaries, and foreign allies with self-serving agendas.[32]

To "Break the will of their domestic opponents and reaffirm their autonomy vis-a-vis their foreign allies"[33] hundreds of pro-Soviet, Northern-first Party members, military officers, and intelligentsia were arrested on 27 July 1967 during what came to be called the Revisionist Anti-Party Affair. All of the arrests were based on the Politburo's choice of tactics and strategy for the Tet Offensive.[34] This move cemented the position of the militants as Hanoi's strategy: The rejection of negotiations, the abandonment of protracted warfare, and the focus on the General Offensive, General Uprising in the towns and cities of South Vietnam. More arrests followed in November and December.

After cementing their position, the militants decided it was time for a major conventional offensive to break the military deadlock. They believed that the South Vietnamese government and the U.S. presence were so unpopular with the population of the South that a broad-based attack would spark a spontaneous uprising of the South Vietnamese population, which, if the offensive was successful, would enable the north to sweep to a quick, decisive victory. Their basis for this conclusion included: their belief that the South Vietnamese military was no longer combat effective; the results of the fall 1967 South Vietnamese presidential election, in which the Nguyen Van Thieu/Nguyen Cao Ky ticket had only received 24 percent of the vote; well-publicized anti-war demonstrations in Saigon; and continuous criticism of the Thieu government in the southern press.[35] Launching such an offensive would also finally end to what were called "dovish calls for talks, criticism of military strategy, Chinese diatribes of Soviet perfidy, and Soviet pressure to negotiate - all of which needed to be silenced."[36]

The resultant Resolution 14 was a major blow to domestic opposition and "foreign obstruction." Concessions were made to the center group by agreeing that negotiations were possible, but the document centered on the creation of "a spontaneous uprising in order to win a decisive victory in the shortest time possible."[37]

Unfortunately, the chief military advocate of such a strategy, General Thanh, was killed as a result of a U.S. air raid on 7 July.[38] Contrary to Western belief, Giap did not plan the offensive himself. Thanh's original plan was elaborated on by a party committee and then modified by Giap.[39] The general may have been been convinced to toe the line by the arrest and imprisonment of most of the members of his staff during the Revisionist Anti-Party Affair. Giap then went to work "reluctantly, under duress".[40]

Giap may have found the task easier since he was faced with a fait accompli. The Politburo had already approved the offensive, all he had to do was make it work. He combined guerrilla operations into what was basically a conventional military offensive and shifted the burden of sparking the popular uprising to the NLF. If it worked, all well and good, but if it failed, it would be a failure only for the Southern-firsters. For the center/moderates and militants it offered the prospect of negotiations and an end to the American bombing of the North. Only in the eyes of the moderates did the offensive become a "go for broke" effort. Others in the Politburo were willing to settle for a much less ambitious "victory."[41]

The operation would involve a preliminary phase during which diversionary attacks would be launched in the border areas to draw American attention and forces away from the cities. The General Offensive, General Uprising would then proceed by launching simultaneous military actions in most of the larger cities of South Vietnam and attacks on major allied bases, with particular emphasis focused on the cities of Saigon and Hue. Concurrently, a substantial threat would to be made against the U.S. combat base at Khe Sanh. The Khe Sanh actions would draw North Vietnamese forces away from the offensive into the cities, but Giap considered it necessary in order to protect his supply lines and divert American attention.[42] Attacks on other U.S. forces were of secondary, or even tertiary importance due to the fact that Giap considered his main objective to be weakening or destroying the South Vietnamese military and government through popular revolt.[43] The offensive, therefore was aimed at the South Vietnamese public, not that of the U.S. Nor was it timed to influence the U.S. presidential election in November.[44]

According to General Tran Van Tra, the new military head of COSVN, the offensive was to have three distinct phases: Phase I, scheduled to begin on 31 January, was to be a country-wide assault on the cities conducted primarily by NLF forces. Concurrently, a propaganda offensive to enduce ARVN troops to desert and the South Vietnamese population to rise up against the government would be launched. If outright victory was not achieved, the battle might still lead to the creation of a coalition government and the withdrawal of the Americans. If the general offensive failed to achieve these purposes, followup operations would be conducted to wear down the enemy and lead to a negotiated settlement; Phase II was scheduled to begin on 5 May; and Phase III on 17 August.[45]

Preparations for the offensive were already underway. The logistical build-up had begun by mid-year, during which 81,000 tons of supplies and 200,000 troops, including seven complete infantry regiments and 20 independent battalions made the trip south on the Ho Chi Minh Trail.[46] This logistical effort also involved the re-arming of the NLF with new AK-47 assault rifles and B-40 rocket-propelled grenades, which granted them superior firepower over their less well-armed ARVN opponents. To pave the way and to confuse the allies as to its intentions, Hanoi launched a diplomatic offensive. Foreign Minister Nguyen Duy Trinh announced on 30 December that Hanoi would rather than could open negotiations if the U.S. unconditionally ended Operation Rolling Thunder, the bombing campaign against North Vietnam.[47] This announcement provoked a flurry of diplomatic activity (which amounted to nothing) during the last weeks of the year.

The ARVN (and U.S. military intelligence) estimated that communist forces in South Vietnam during January 1968 totaled 323,000 men, including 130,000 PAVN regulars, 160,000 NLF guerillas and members of the infrastructure, and 33,000 service and support troops. They were organized into nine divisions composed of 35 infantry regiments and 20 artillery or anti-aircraft artillery regiments, which were, in turn, composed of 230 infantry and six sapper battalions.[48]

Suspicions

Signs of impending communist action did not go unnoticed among the intelligence collection apparatus in Saigon. During the late summer and fall of 1967, both South Vietnamese and U.S. intelligence agencies collected clues that indicated a significant shift in PAVN/NLF strategic planning. By mid-December, mounting evidence convinced many in Washington and Saigon that something big was underway. During the last three months of the year, for example, intelligence agencies had observed signs of a major communist military buildup. In addition to captured documents (a copy of Resolution 13, for example, was captured by early October), observations of enemy logistical operations were also quite clear: in October the number of trucks observed heading south through Laos on the Hồ Chí Minh Trail jumped from the previous monthly average of 480 to 1,116. By November this total reached 3,823 and, in December, 6,315.[49] On 20 December Westmoreland cabled Washington that he expected the communists "to undertake an intensified countrywide effort, perhaps a maximum effort, over a relatively short period of time."[50]

Despite all the warning signs, the allies were still surprised by the scale and scope of the offensive - Why? Accordng to Colonel Hoang Ngoc Lung, the answer lay with the intelligence methodology itself, which tended to estimate the enemy's probable course of action based on his capabilities, not his intentions. Since, in the allied estimation, the communists hardly had the capability to launch such an ambitious enterprise "There was little possibility that the enemy could initiate a general offensive, regardless of his intentions."[51] The answer could also be partially explained by the lack of coordination and cooperation between competing intelligence branches, both South Vietnamese and American. The situation from the U.S. perspective was best summed up by a MACV intelligence analyst: "If we'd gotten the whole battle plan, it wouldn't have been believed. It wouldn't have been credible to us."[52]

From spring through the fall of 1967, the U.S. command in Saigon was perplexed by a series of actions initiated by the North Vietnamese and the NLF in the border regions. On 24 April a U.S. Marine Corps patrol prematurely triggered a PAVN offensive aimed at taking the airstrip and combat base at Khe Sanh, the western anchor of the Marine's defensive positions in Quang Tri Province. By the time the action there had ended in May, 940 North Vietnamese troops and 155 Marines had been killed.[53] For 49 days during early September and lasting into October, the North Vietnamese began shelling the U.S. Marine outpost of Con Thien, just south of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). The intense shelling (100-150 rounds per day) prompted Westmoreland to launch Operation Neutralize, an intense aerial bombardment campaign of 4,000 sorties into and just north of the demarcation line.[54]

On 27 October, an ARVN battalion at Song Be, the capital of Phuoc Long Province, came under attack by an entire PAVN regiment. Two days later, another PAVN Regiment attacked a U.S. Special Forces border outpost at Loc Ninh, in Binh Long Province. This attack sparked a ten-day battle that drew in elements of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division and the ARVN 18th Division. The fighting left 800 PAVN troops dead.[55] The most severe of what came to be known as "the Border Battles" erupted occurred during October and November around Dak To, another border outpost in Kontum Province. The clashes between the three regiments of the 1st PAVN Division, the U.S. 4th Infantry Division, the U.S. 173rd Airborne Brigade, and ARVN infantry and Airborne elements, lasted for 22 days. By the time the fighting was over, between 1,200 and 1,600 North Vietnamese and 262 U.S. troops had lost their lives.[56] MACV intelligence was confused by the possible motives of the North Vietnamese in prompting such large-scale actions in remote regions where U.S. firepower and aerial might could be applied indiscriminately. Tactically and strategically, these operations made no sense. What the communists had done was carry out the first stage of their plan: to fix the attention of the U.S. command on the borders and draw the bulk of U.S. forces away from the heavily populated coastal lowlands and cities.[57]

Westmoreland was more concerned with the situation at Khe Sanh, where, on 21 January, a force estimated at between 20,000-40,000 North Vietnamese troops had besieged the U.S. Marine combat base. MACV was convinced that the enemy planned to stage an attack and overrun the base as a prelude to an all-out effort to seize the two northernmost provinces of South Vietnam.[58] To deter any such possibility, Westmoreland deployed 250,000 men, including half of MACV's U.S. maneuver battalions, to the I Corps Tactical Zone.

This course of events disturbed Lieutenant General Frederick C. Weyand, commander of U.S., forces in II Corps, which included the city of Saigon. Weyand, a former intelligence officer, was suspicious of the pattern of PAVN/NLF activities in his area of responsibility and notified Westmoreland of his concerns on 10 January. His commander agreed and ordered 15 U.S. battalions to redeploy from positions near the Cambodian border back to the outskirts of the capital.[59] When the offensive did begin, a total of 27 allied maneuver battalions defended Saigon and the surrounding area. This redeployment may have been one of the most critical tactical decisions of the war.[60]

By the beginning of January 1968, the U.S had deployed 331,098 army personnel and 78,013 marines in nine divisions, an armoured cavalry regiment, and two separate brigades to South Vietnam. They were joined there by the 1st Australian Task Force, a Royal Thai Army regiment, two Korean divisions, and a Korean Marine Corps brigade.[61] South Vietnamese army strength totaled 350,000 regulars in the Army, Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps.[62] They were, in turn, supported by the 151,000-man Regional Forces and 149,000-man Popular Forces, which were the equivalent of regional and local militias.[63]

In the days immediately preceeding the offensive, the preparedness of both the ARVN and the U.S. military were relatively relaxed. North Vietnam had announced in October that it would observe a seven-day truce from 27 January to 3 February in honor of the Tet holiday, and the South Vietnamese military made plans to allow recreational leave for approximately one-half of its forces. General Westmoreland, who had already cancelled the truce in I Corps, requested that its ally cancel the upcoming cease-fire, but South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu (who had already reduced the cease-fire to 36 hours), refused to do so, claiming that it would damage troop morale and only benefit communist propagandists.[64]

On 28 January 11 NLF cadre were captured in Qui Nhon in possession of two pre-recorded audio tapes whose message appealed to the populace in "already occupied Saigon, Hue, and Da Nang."[65] The following afternoon, General Cao Van Vien, chief of the ARVN General Staff, ordered all his corps commanders to place their troops on alert. Yet, there was still a lack of a sense of urgency on the part of the allies. Although Westmoreland may have had a grasp of the potential for danger, it was not communicated very well to others. On the evening of 30 January 200 U.S. colonels, all on the MACV intelligence staff, attended a pool party at the officer's quarters in Saigon. According to James Meecham, an analyst at the Combined Intelligence Center who attended the party: "I had no conception Tet was coming, absolutely zero...Of the 200-odd colonels present, not one I talked to knew Tet was coming, without exception."[66] The general also failed to communicate his concerns adequately to the administration. Although he had warned Washington between 25 and 30 January that "widespread" communist attacks were in the offing, he meant ten or twenty, not the fifteen times that number that occurred.[67] No one - in either Washington or Vietnam - was expecting what happened.

Offensive

"Crack the Sky, Shake the Earth"

Whether by accident or design, the first wave of attacks began shortly after midnight on 30 January as all five provincial capitals in II Corps and Da Nang, in I Corps, were attacked.[68] Nha Trang, headquarters of the U.S. I Field Force, was the first to be hit, followed shortly by Ban Me Thuot, Kontum, Hoi An, Tuy Hoa, Da Nang, Qui Nhon, and Pleiku. During all of these operations, the communists followed a similar pattern: mortar and/or rocket attacks were closely followed by massed ground assaults conducted by battalion-strength elements of the NLF (sometimes supported by North Vietnamese regulars). These forces would join with local NLF cadres who served as guides to lead the regulars to the highest South Vietnamese local headquarters and the radio station. The operations, however, were not well coordinated and, by daylight, almost all communist forces had been driven from their objectives. General Phillip B. Davidson, the new MACV chief of intelligence, notified Westmoreland that "This is going in the rest of the country tonight and tomorrow morning."[69] All U.S. forces were placed on maximum alert and similar orders were issued to all ARVN units. The allies, however, still responded without any real sense of urgency. Orders cancelling leaves either came too late or were disregarded.[70]

At 03:00 on the morning of 31 January NLF and PAVN forces assailed Saigon, Cholon, and Gia Dinh in the Capital Military District; Quang Tri (again), Hue, Quang Tin, Tam Ky, and Quang Ngai as well as U.S. bases at Phu Bai and Chu Lai in I Corps; Phan Thiet, Tuy Hoa, and U.S. installations at Bong Son and An Khe in II Corps; and Can Tho and Vinh Long in IV Corps. The following day, Bien Hoa, Long Thanh, Binh Duong in III Corps and Kien Hoa, Dinh Tuong, Go Cong, Kien Giang, Vinh Binh, Ben Tre, and Kien Tuong in IV Corps were assaulted. The last attack of the initial operation was launched against Bac Lieu in IV Corps on 10 February. A total of approximately 84,000 communist troops participated in the attacks while thousands of others stood by to act as reinforcements or as blocking forces.[71] Communist forces also mortared or rocketed every major allied airfield and attacked 64 district capitals and scores of smaller towns.

In most cases the defense against the General Offensive was a South Vietnamese affair. Local militia or ARVN forces, supported by the National Police, usually drove the attackers out within two or three days, sometimes within hours; but heavy fighting continued several days longer in Kontum, Ban My Thuot, Phan Thiet, Can Tho, and Ben Tre.[72] The outcome in each instance was usually dictated by the ability of local commanders. Some were outstanding, some were cowardly and/or incompetent, during this crucial crisis, however, no South Vietnamese unit had broken or defected to the communists.[73]

General Westmoreland responded to the news of the attacks with optimism, both in media presentations and in his reports to Washington. According to closer observers, however, the general was "stunned that the communists had been able to coordinate so many attacks in such secrecy" and he was "dispirited and deeply shaken."[74] Although his appraisal of the situation was was correct, he made himself look foolish by continuously maintaining his belief that Khe Sanh was the real objective of the communists and that 155 attacks by 84,000 troops was a diversion.[75] Washington Post reporter Peter Braestrup summed up the feelings of his colleagues by asking "How could any effort against Saigon, especially downtown Saigon, be a diversion?"[76]

Saigon

Although Saigon was the focal point of the offensive, the communists did not seek a total takeover of the city.[77] Rather, they had six primary targets to strike in the downtown area: the headquarters of the ARVN General Staff; the Independence Palace, the American Embassy, the Long Binh Naval Headquarters, and the National Radio Station. These objectices were assaulted by small elements of the local C-10 Sapper Battalion. In the outskirts, ten NLF Local Force Battalionsl attacked the central police station, the Artillery Command and the Armored Command headquarters (both at Go Vap), and the Naval headquarters. The plan called for all these initial forces to capture and hold their positions for 48 hours, by which time reinforcements would arrive to relieve them.

The defense of the Capital Military Zone was primarily a South Vietnamese responsibility, and it was initially defended by eight ARVN infantry battalions and the local police force. By 3 February they had been reinforced the five ARVN Ranger Battalions, five Marine Corps, and five ARVN Airborne Battalions. U.S. Army units participating in the defense included the 716th Military Police Battalion, seven infantry battalions (one mechanized), and six artillery battalions.[78]

Faulty intelligence and poor local coordonation hampered the communist attacks from the outset. At the Armored Command and Artillery Command headquarters at Go Vap, on the northern edge of the city, for example, the communists planned to utilize captured tanks and artillery pieces to further support the offensive. To their dismay, they found that the tanks had been moved to another base two months earlier and that the breech blocks of the artillery pieces had been removed, rendering them useless.[79] One of the most important NLF targets was the National Radio Station. NLF troops had brought along a tape recording of Hồ Chí Minh announcing the liberation of Saigon and calling for a "General Uprising" against the Thieu regime. The building was seized and held for six hours, but the occupiers were unable to broadcast due to the cutting off of the audio lines from the main studio at the tower (which was situated at a different location) as soon as the station was seized.

The U.S. Embassy in Saigon, a massive six-floor building situated within a four acre compound, had only been completed in September. At 02:45 it was attacked by a 19-man sapper team that blew a hole in the eight-foot high surrounding wall and charged through. With their officer killed in the initial attack and their attempt to gain access to the building having failed, however, the sappers simply milled around in the chancery grounds until they were all eliminated by reinforcements. By 09:20 the embassy and its grounds were secured. It was interesting that the embassy attack, which became such a cause celebre in the U.S. media, had been entrusted to so few men. It had in fact been aimed at impressing the South Vietnamese population, not the Americans.[80]

Throughout the city, small squads of NLF troops fanned out to attack various officers and enlisted men's billets, homes of ARVN officers, and district police stations. Provided with "blacklists" of military officers and civil servants, they began to round up and execute any that could be found. Brutality begat brutality. On 1 February General Nguyen Ngoc Loan, chief of the National Police Force, publically executed an NLF officer captured in civilian clothes in front of a photographer and film cameraman. What was not explained in the lurid wake of their distribution in the U.S. was that the suspect had just taken part in the murder of one of Loan's most trusted officers and his entire family.[81]

Outside the city proper, the two NLF battalions attacked the U.S. logistical and headquarters complex at Long Binh. Bien Hoa Air Base was struck by a battalion, while the adjacent ARVN III Corps headquarters was the objective of another. Tan Son Nhut Air Base, in the northwestern part of the city, was attacked by three battalions. Fortunately for the allies, a combat-ready battalion of ARVN paratroopers, awaiting transport to Da Nang, went inbstead directly into action and halted the attack.[82] A total of 35 communist battalions, many of whose troops were undercover cadres who had lived and worked within the city or its environs for years, had been committed to the Saigon objectives.[83] By dawn, most of the attacks within the city center had been eliminated, but severe fighting between NLF and allied forces erupted in the Chinese suburb of Cholon around the Phu Tho racetrack, which was being utilized as an NLF staging area and command and control center. Bitter and destructive house-to-house fighting erupted in the area and, on 4 February, the residents of Cholon were ordered to leave their homes and the area was declared a free fire zone. Fighting in the city came to a close only after a fierce battle between ARVN Rangers and NLF forces on 7 March.

Except at Hue and mopping-up operations in and around Saigon, the first phase of the offensive was over by the second week of February. From the initial attacks on 29 January through 11 February, NLF/PAVN forces had lost 32,000 killed in action and 5,800 captured. U.S. losses included 1,001 killed, South Vietnamese and allied forces, 2,082.[84]

Huế

At 03:40 on the foggy morning of 31 January, allied defensive positions north of the Perfume River in the city of Hue were mortared and rocketed and then attacked by two battalions of the 6th PAVN Regiment. Their targets were the ARVN 1st Division headquarters located in the Citadel, a three-square mile complex of palaces, parks, and residences that were surrounded by a moat and a massive earth and masonry fortress built in 1802. The undermanned ARVN defenders, led by General Ngo Quang Truong, managed to hold their positions, but the majority of the Citadel fell to the communists. On the south bank of the river, the 4th PAVN Regiment attempted to seize the local MACV headquarters, but were held at bay by a makeshift force of approximately 200 Americans. The rest of the city was overrun by PAVN/NLF forces which initially totaled approximately 7,500 men.[85] Both sides then rushed to reinforce and resupply their forces. Lasting 26 days, the battle of Huế became one of the longest and bloodiest single battles of the Vietnam War.

During the first days of the PAVN occupation, allied intelligence vastly underestimated the number of communist troops and little appreciated the effort that was going to be necessary to evict them. General Westmoreland informed the Joint Chiefs that "the enemy has approximately three companies in the Hue Citadel and the marines have sent a battalion into the area to clear them out."[86] Since there were no U.S. formations stationed in Hue, relief forces had to move up from Phu Bai, eight kilometers to the southeast. In a misty drizzle, U.S. Marines of the 1st Marine Division and soldiers of the 1st ARVN Division and Marine Corps cleared the city street by street and house by house, a deadly and destructive form of urban combat that the U.S. military had not engaged in since the Battle of Seoul during the Korean War, and for which its men were not trained.[87] Due to the historical and cultural significance of the city, American forces did not immediately apply air and artillery strikes as widely as it had in other cities.

Outside the city, elements of the U.S. 1st Air Cavalry Division and the 101st Airborne Division fought to seal communist access and cut off their line of supply and reinforcement. By this point in the battle 16 to 18 PAVN/NLF battalions (8,000-11,000 men) were taking part in the fighting for the city itself or the approaches to the former imperial capital.[88] Two of the PAVN regiments had made a forced march from the vicinity of Khe Sanh to Hue in order to participate. During most of February, the allies gradually fought their way towards the Citadel, which was only taken after four days of intense struggle. The city was not declared recaptured by U.S. and ARVN forces until 24 February, when members of the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Regiment, 1st ARVN Division raised the South Vietnamese flag over the Palace of Perfect Peace.

During the intense action, the allies estimated that North Vietnamese forces had between 2,500 and 5,000 killed and 89 captured in the city and in the surrounding area.[89] 216 U.S. Marines and soldiers had been killed during the fighting and 1,609 were wounded. 421 ARVN troops were killed another 2,123 were wounded and 31 were missing.[90] More than 5,800 civilians had lost their lives during the battle and 116,000 were left homeless out of an original population of 140,000.[91]

In the aftermath of the recapture of the city, the discovery of several mass graves (the last of which were uncovered in 1970) of South Vietnamese citizens sparked a controversy that has not diminished with time. The victums had either been clubbed or shot to death or simply been buried alive. The initial allied explanation was that during their initial occupation of the city, the communists had quickly begun to systematically round up (under the guise of re-education) and then execute as many as 2,800 South Vietnamese civilians that they believed to be potentially hostile to communist control.[92] Those taken into custody included South Vietnamese military personnel, present and former government officials, local civil servants, teachers, policemen, and religious figures

This thesis achieved wide creedence at the time, but it came under increasing scrutiny later, when it became known that South Vietnamese "revenge squads" had also been at work in the aftermath of the battle, searching out and executing citizens that had supported the communist occupation.[93] The North Vietnamese later further muddied the waters by stating that their forces had indeed rounded up "reactionary" captives for transport to the north, but that local commanders, under battlefield exegencies, had executed them for expediency's sake.[94] General Truong, commander of the 1st ARVN Division and hero of the battle, believed that the captives had been executed by the communists in order to protect the identities of members of the local NLF infrastructure, whose covers had been blown.[95] The fate of those citizens of Hue discovered in the mass graves will probably never be known with certainty, but it was probably the result of a combination of all of the above circumstances.

Khe Sanh

The Khe Sanh Combat Base was the northwestern anchor U.S. Marine Corps' defensive line below the DMZ in Quang Tri Province. As far as can be presently ascertained, the attack on Khe Sanh, which began on 21 January, could have been intended to serve two purposes - as a real attempt to seize the position or as a diversion to draw American attention and forces away from the population centers in the lowlands, a deception that was "both plausible and easy to orchestrate."[96] In General Westmoreland's view, the purpose of the Combat Base was to provoke the North Vietnamese into a focused and prolonged confrontation in a confined geographic area, one which would allow the application of massive U.S. artillery and air strikes that would inflict heavy casualties in a relatively unpopulated region.[97] By the end of 1967, MACV had moved nearly half of its maneuver battalions to I Corps in anticipation of just such an battle.

Westmoreland (and the American media, which covered the action extensively) often made inevitable comparisons between the actions at Khe Sanh and the Battle of Dien Bien Phu, where a French base had been besieged and ultimately overrun by Viet Minh forces under the command of General Giap during the First Indochina War.[98] Westmoreland, who knew of Nguyen Chi Thanh's penchant for large-scale operations (but not of his death) believed that this was going to be an attempt to replicate that victory. He intended to stage his own "Dien Bien Phu in reverse."[99]

Khe Sanh and its 6,000 Marine Corps, Army, and ARVN defenders were surrounded by two to three PAVN divisions, totaling approximately 20,000 men. Throughout the siege, which lasted until 8 April, the marines were subjected to heavy mortar, rocket, and artillery bombardment, combined with sporadic small-scale infantry attacks on outlying positions. With the exception of the overrunning of the U.S. Special Forces camp at Battle of Lang Vei, however, there was never a major ground assault on the base and the battle became largely a duel between American and North Vietnamese artillerists, combined with massive air strikes conducted by U.S. aircraft. American air support included massive bombing strikes by B-52s. By the end of the siege, U.S Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy aircraft had dropped 39,179 tons of ordnance in the defense of the base.[100].

The overland supply route to the base had been cut off, and airborne resupply by cargo aircraft became extremely dangerous due to heavy North Vietnamese antiaircraft fire. Thanks to innovative high-speed "Super Gaggles," which utilized fighter-bombers in combination with large numbers of supply helicopters, and the Air Force's utilization of C-130 Hercules cargo aircraft employing the innovative LAPES delivery method, aerial resupply was never halted.

When the Tet Offensive began, feelings ran high at MACV that the base was in for a serious attack. In I Corps, the Tet truce had been cancelled in apprehension of just such an occurrence. It just never happened. The offensive passed Khe Sanh by and the intermittent battle continued there as usual. Westmorland's fixation upon the base continued even as the battle raged around him in Saigon.[101] On 1 February, as the offensive reached its height, he wrote a memo for his staff (but never delivered) claiming that "The enemy is attempting to confuse the issue...I suspect he is also trying to draw everyone's attention from the area of greatest threat, the northern part of I Corps. Let me caution everyone not to be confused."[102]

In the end, a major allied relief expedition (Operation Pegasus) reached Khe Sanh on 8 April, but North Vietnamese forces were already withdrawing from the area.[103] Both sides claimed that the battle had served its intended purpose. The U.S. estimated that 8,000 PAVN troops had been killed and considerably more wounded, against 730 American lives lost and another 2,642 wounded.[104]

Phases II and III

To further enhance their political posture at the Paris talks, which opened on 13 May, the North Vietnamese opened the second phase of the General Offensive in late April and early May. U.S. intelligence sources estimated that from February through May the North Vietnamese had dispatched 50,000 men down the Ho Chi Minh Trail to replace losses incurred during the earlier fighting.[105] Some of the most prolonged and viscious fighting of the war opened on 29 April and lasted until 30 May when the 8,000 men of the 320th PAVN Division, backed by artillery from across the DMZ, threatened the U.S. logistical base at Dong Ha, in northwestern Quang Tri Province. In what decame known as the Battle of Dai Do, the North Vietnamese clashed savagly with Marines, U.S. Army, and ARVN forces before withdrawing. PAVN lost an estimated 2,100 men after inflicting casualties on the allies of 290 killed and 946 wounded.[106]

During the early morning hours of 4 May, communist units initiated second phase of the offensive (known by the South Vietnamese and Americans as "Mini-Tet") by striking 119 targets throughout South Vietnam, including Saigon. This time, however, allied intelligence was better prepared, stripping away the element of surprise. Most of the communist forces were intercepted by allied screening elements before they reached their targets. 13 NLF battalions, however, managed to slip through the cordon and once again plunged the capital into chaos. Severe fighting occurred at Phu Lam, (where it took two days to root out the 267th NLF Local Force Battalion), around the Y-Bridge, and at Tan Son Nhut.[107] By 12 May, however, it was all over. NLF forces withdrew from the area leaving behind over 3,000 dead.[108]

The fighting had no sooner died down around Saigon than U.S. forces in Quang Tin Province suffered what was, without doubt, the most serious American defeat of the war. On 10 May two regiments of the 2nd PAVN Division attacked Kham Duc, the last Special Forces border surveillance camp in I Corps. 1,800 U.S. and South Vietnamese troops were isolated and under intense attack when MACV made the decision to avoid a situation reminiscent of that at Khe Sanh. The camp was evacuated under fire by air and abandoned to the North Vietnamese.[109]

The communists returned to Saigon on 25 May and launched a second wave of attacks on the city. The fighting during this phase differred from Tet Mau Than and "Mini-Tet" in that no U.S. installations were attacked. During this series of actions, NLF forces occupied six pagodas in the mistaken belief that they would be immune from artillery and air attack. The fiercest fighting once again took place in Cholon. One notable event occurred on 18 June when 152 members of the NLF Quyet Thang Regiment surrendered to ARVN forces, the largest communist surrender of the war.[110] During the third phase, 143 ARVN soldiers were killed and another 643 were wounded. 67 U.S. troops were also killed and 333 were wounded.[111] The actions also brought more death and suffering to the city's inhabitants. 87,000 more had been made homeless while more than 500 were killed and another 4,500 were wounded.[112]

Phase III of the offensive began on 17 August and involved attacks in I, II, and III Corps. Significantly, during this series of actions only PAVN forces participated. The main offensive was preceeded by attacks on the border towns of Tay Ninh, An Loc, and Loc Ninh, which were initiated in order to draw defensive forces from the cities.[113] A thrust against Da Nang was prempted by the U.S. marines on 16 August. Continuing their border-clearing operations, three North Vietnamese regiments asserted heavy pressure on the U.S. Special Forces camp at Duc Lap, in Quang Duc Province. The fighting lasted for two days but the camp managed to survive. Saigon was struck again, but the attacks were less sustained and once again easily repulsed. As far as MACV was concerned, the August offensive "was a dismal failure."[114] In five weeks of fighting and after the loss of 20,000 troops, not a single objective had been attained during this "final and decisive phase." Yet, as historian Ronald Spector has pointed out "the communist failures were not final or decisive either."[115]

The horrendous casualties and suffering endured by NLF/PAVN units during these sustained operations was beginning to tell. The fact that there were no apparent military gains made that could possibly justify all the blood and effort just exacerbated the situation. During the first half of 1969, more than 20,000 communist troops rallied to allied forces, a three-fold increase over the 1968 figure.[116] On 5 April 1969, COSVN issued Directive 55 to all of its subordinate units: "Never again and under no circumstances are we going to risk our entire military force for just such an offensive. On the contrary, we should endeavor to preserve our military potential for future campaigns."[117]

Aftermath

In total, approximately 85,000-100,000 NLF and PAVN troops had participated in the initial onslaught and in the follow-up attacks. The U.S. estimated that during the first phase, approximately 45,000 NLF and PAVN soldiers were killed. For years this figure was held as excessive, that was until it was confirmed by Stanley Karnow in Hanoi in 1981.[118] U.S., ARVN, and allied forces suffered 4,324 killed, 16,063 wounded, and 598 missing.[119]

Phase II-

Phase III - MACV estimated that 10,000 NLF/PAVN troops were killed. During the same period 700 U.S. troops were killed.[120] During the year 14,521 American troops were killed in Vietnam.[121] Communist troop strength - MACV estimated 330,000, the CIA and State department considered 435,000-595,000 a more reliable figure.[122]

Overall, during the nine-month winter-spring campaign (including the "border battles"), Tet Mau Than, and Phase II, 85,000 NLF and PAVN troops had been killed.[123]

North Vietnam

The leadership in Hanoi must have been initially despondent about the outcome of their great gamble. Their first and most ambitious goal, producing a general uprising, had ended in a dismal failure. The keys to the failure of the Tet Offensive were not difficult to discern. Hanoi had underestimated the strategic mobility of the allied forces, which allowed them to redeploy forces at will to threatened areas; their battle plan was too complicated and difficult to coordinate, which was amply demonstrated by the 30 January attacks; their violation of the principal of mass, attacking everywhere instead of concentrating their forces on a few specific targets allowed their forces to be defeated piecemeal; the launching of massed attacks headlong into the teeth of vastly superior firepower; and last, but not least, the incorrect assumptions upon which the entire campaign was based.[124]

According to General Tran Van Tra: "We did not correctly evaluate the specific balance of forces between ourselves and the enemy, did not fully realize that the enemy still had considerable capabilities, and that our capabilities were limited, and set requirements that were beyond our actual strength.[125]

Their effort to regain control of the countryside was somewhat more successful. According to the U.S. State Department the NLF "expanded their control in urban areas and have made pacification virtually inoperative. In the Mekong Delta the NLF was stronger now then ever and in other regions the countryside belongs to the VC."[126] General Wheeler reported that the Tet Offensive had brought counterinsurgency programs to a halt and "that to a large extent, the V.C. now controlled the countryside."[127]Unfortunately for the NLF, this state of affairs did not last. Heavy casualties and the backlash of the South Vietnamese and Americans resulted in more territorial losses and heavy casualties.[128]

The horrendous casualties inflicted on NLF units struck into the heart of the irreplaceable infrastructure that had been built up for over a decade. From this point forward, Hanoi was forced to fill one-third of the NLF's ranks with North Vietnamese troops. Some Western historians have come to believe that one insidious alterior motive for the campaign was the elimination of competing southern members of the party, thereby allowing the northerners more control once the war was won.[129] However, this change had little effect on the war, since North Vietnam had little difficulty making up the casualties inflicted by the offensive.[130]

It was not until after the conclusion of the first phase of the offensive that Hanoi realized that its sacrifices had not been in vain. General Tran Do, PAVN commander at the battle of Hue gave some insight into how defeat was translateds into victory:

In all honesty, we didn't achieve our main objective, which was to spur uprisings throughout the south. Still, we inflicted heavy casualties on the Americans and their puppets, and this was a big gain for us. As for making an impact in the United States, it had not been our intention - but it turned out to be a fortunate result.[131]

Hanoi had in no way anticipated the political and psychological effect the offensive would have on the leadership and population of the U.S.[132] When the northern leadership saw how the U.S. was reacting to the offensive, they began to propagandize their "victory". The opening of negotiations and the diplomatic struggle, the option feared by the Southern-firsters prior to the offensive, quickly came to occupy a position equal to that of the military struggle.[133] Unfortunately, many of those who had espoused just such a strategy did not live to see the success of their initiative.

On 5 May Truong Chinh rose to address a congress of party members and proceeded to castigate the Southern-firsters and their bid for quick victory. His "faction-bashing" tirade sparked a serious debate within the party leadership which lasted for four months. As the leader of the "main force war" and "quick victory" faction, Le Duan also came under severe criticism. In August Chinh's report on the situation was accepted in toto, published, and broadcast via Radio Hanoi. He had single-handedly shifted the nation's war strategy and restored himself to prominence as the party's ideological conscience.[134] Meanwhile, the NLF reformed itself as the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam, and took part in future peace negotiations under this title. It would be a long seven years until victory.

South Vietnam

South Vietnam was a nation in turmoil both during and in the aftermath of the offensive. Tragedy compounded tragedy as the conflict reached into the nation's cities for the first time. As government troops pulled back to defend the urban areas, the NLF moved in to fill the vacuum in the countryside. The violence and destruction witnessed during the offensive left a deep psychological scar on the South Vietnamese civilian population. Confidence in the government was shaken, since the offensive seemed to reveal that even with massive American support, the government could not protect its citizens.[135]

The human and material cost to South Vietnam was staggering. The number of civilian dead was estimated by the government at 14,300 with an additional 24,000 wounded.[136] 630,000 new refugees had been generated, joining the nearly 800,000 others already displaced by the war. One of every twelve South Vietnamese was now living in a refugee camp.[137] More than 70,000 homes had been destroyed in the fighting and perhaps 30,000 more were heavily damaged. The nation's infrastructure was virtually destroyed. The South Vietnamese army, although it had performed better than the Americans expected it to, suffered from lowered morale, with desertion rates rising from 10.5 per thousand before Tet to 16.5 per thousand by July.[138]

In the wake of Tet, however, fresh determination was exhibited by Thieu government. On 1 February the President declared a state of martial law and, on 15 June the National Assembly passed his request for a general mobilization of the population and the induction of 200,000 draftees into the armed forces by the end of the year (a decree that had failed to pass due to strong political opposition only five months previously).[139] This would bring South Vietnam's troop strength to more than 900,000 men.[140] Military mobilization, anti-corruption drives, demonstrations of political unity, and administrative reforms were quickly carried out.[141] Thieu also established a National Recovery Committee to oversee food distribution, resettlement, and housing construction for the new refugees. Both the government and the Americans were encouraged by a new determination that was exhibited among the ordinary citizens of South Vietnam. Many city dwellers were indignant that the NLF had launched their attacks during Tet and it drove many who had been previously apathetic into active support of the government. Journalists, political figures, and religious leaders alike - even the militant Buddhists - professed confidence in the government's plans.[142]

Thieu saw an opportunity to consolidate his personal power and he took it. His only real rival was Vice President Nguyen Cao Ky, the former Air Force commander, who had been outmaneuvered by Thieu in the presidential election of 1967. In the aftermath of Tet, Ky supporters in the military and the administration were quickly removed from power, arrested, or exiled.[143] A crack-down on the South Vietnamese press also ensued and there was a worrysome return of former President Ngo Dinh Diem's Can Lao Party members to high positions in Thieu's government and military. By the summer of 1968, President Thieu had earned a less exalted title among the South Vietnamese population, who had begun to call him "the little dictator."[144]

Thieu had also become very suspicious of his American allies, unwilling to believe (as did many South Vietnamese) that the U.S. had been caught by surprise by the offensive. "Now that it's all over," he queried a visiting Washington official, "you really knew it was coming didn't you?"[145] Lyndon Johnson's unilateral decision on 31 March to curtail the bombing of North Vietnam only confirmed what Thieu already feared - the Americans were going to abandon South Vietnam to the communists. The bombing halt and the beginning of negotiations with the North brought not the hope of an end to the war, but "an abiding fear of peace."[146] Thieu was only mollified after an 18 July meeting with Johnson in Honolulu, where the American president affirmed that Saigon would be a full partner in all negotiations and that the U.S. would not "support the imposition of a coalition government, or any other form of government, on the people of South Vietnam."[147]

United States

The Tet Offensive created a crisis in the Johnson administration, which was unable to convince the American public that the offensive had been a major defeat for the communists. The optimistic assessments of the administration and the Pentagon came under heavy criticism and ridicule as the "credibility gap" that had opened in 1967 widened into a chasm. The offensive also had a profound psychological impact on the administration, elite decision makers, and the public. On 13 February 10,000 U.S. replacements were airlifted to Vietnam and on the 17th MACV posted the highest U.S. casualty figures for a single week during the entire war - 543 killed, 2,547 wounded. On 23 February the Selective Service System announced a new draft call for 48,000 men, the second highest of the war.[148] On 28 February Robert S. McNamara, the Secretary of Defense who had overseen the escalation of the war but who had turned against it, stepped down from office.

During the first two weeks of February, Westmoreland and Wheeler communicated as to the nesessity for reinforcements or troop increases. Westmoreland insisted that he only needed those forces either in-country or already on the way and he was puzzled by the sense of unwarranted urgency in Wheeler's queries.[149] Westmoreland was tempted, however, when Wheeler emphasized that the White House might loosen restraints and allow operations in Laos, Cambodia, or possibly even North Vietnam itself.[150] On 8 February Westmoreland responded that he could use another division "if operations in Laos are authorized".[151] Wheeler responded by challenging Westmoreland's assessment of the situation, pointing out dangers that his on-the-spot commander did not consider palpable, concluding: "In summary, if you need more troops, ask for them."[152]

Wheeler's bizarre promptings were influenced by the severe strain imposed upon the U.S. military by the Vietnam commitment, one which had been undertaken without the mobilization of it's reserve forces. The Joint Chiefs had repeatedly requested national mobilization, not only to prepare for possible intensification of the war, but to ensure that the nation's strategic reserve did not become depleted.[153] By obliquely ordering Westmoreland to demand more forces, Wheeler was attempting to kill two birds with one stone.[154] In comparison to MACV's former communications, which had been full of confidence, optimism, and resolve, Westmoreland's 12 February request for 10,500 troops was much more urgent: "which I desperately need...time is of the essence."[155] The Joint Chiefs then played their hand, advising President Johnson to turn down MACV's request (a request that Wheeler had coaxed out of Westmoreland), unless he called up some 120,000 marine and army reservists.[156]

This caused consternation within the White House and, on 20 February, Johnson sent Wheeler to Vietnam to determine military requirements in response to the offensive. Both Wheeler and Westmoreland were elated that in only eight days McNamara would be replaced by the hawkish Clark Clifford and that the military might finally obtain permission to widen the war, possibly even into North Vietnam itself.[157] Wheeler's written report of the trip, however, contained no mention of any new contingencies, strategies, or the building up the strategic reserve. It was couched in grave alnguage that suggested that the 206,756-man request it proposed (only 108,000 of whom would be sent to Vietnam) was a matter of vital military necessity.[158] Westmoreland wrote in his memoir that Wheeler had deliberately concealed the truth of the matter in order to force the issue of the strategic reserve upon the president.[159]

Clark Clifford, the new defense secretary, had already pointed out the same dilemma on 9 February. At a meeting with Johnson and McNamara, he elaborated on the contradiction of declaring a victory during Tet and simultaneously reporting that "the situation is more dangerous today than it was before all of this."[160] According to the Pentagon Papers, "A fork in the road had been reached and the alternatives stood out in stark reality." To meet Wheeler's request would mean a total U.S. military commitment to South Vietnam. "To deny it, or to attempt to cut it to a size which could be sustained by the thinly stretched active forces, would just as surely signify that an upper limit to the U.S. military commitment in South Vietnam had been reached."[161]

To evaluate Westmoreland's request and its possible impact on domestic politics, Johnson convened the "Clifford Group", on 28 February and called for a complete policy reassessment.[162] Some of the members argued that the offensive represented an opportunity to defeat the North Vietnamese on the U.S.' terms while others argued that neither side could win militarily, that North Vietnam could match any troop increase, that the bombing of the North be halted, and that a change in strategy was required that would seek not victory, but the staying power required to reach a negotiated settlement. This would require a less aggressive strategy that was designed to protect the population of South Vietnam. [163] The divided group's final report, issued on 4 March, "failed to seize the opportunity to change directions... and seemed to recommend that we continue rather haltingly down the same road."[164]

While this was being deliberated, the troop request was leaked by Townsend Hoopes to the press and published in the The New York Times on 10 March. The article also revealed that the request had begun a serious debate within the administration. According to the article, many high-level officials believed that the U.S. troop increase would be matched by the communists and would simply maintain a stalemate at a higher levels of violence. It went on to state that officials were saying in private that "widespread and deep changes in attitudes, a sense that a watershed has been reached."[165]

On 25 March Johnson called a conclave of the "Wise Men".[166] With few exceptions, all of the members of the group had formerly been accounted as hawks on the war. The group was joined by Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Wheeler, Bundy, Rostow, and Clifford. The final assessment of the majority stupified the group.[167] All but four members called for disengagement from the war, leaving President Johnson "deeply shaken."[168] According to the Pentagon Papers, the advice of the group was decisive in convincing Johnson to reduce the bombing of North Vietnam.[169]

During the month of March, Clifford, who had entered office as a staunch supporter of the war and who had opposed McNamara's de-escalatory views, had turned against the war. He was convinced that the troop increase would lead only to a more violent stalemate and sought out others in the administration to assist him in convincing the President to reverse the escalation, to cap force levels at 550,000, to seek negotiations with Hanoi, and turn responsibility for the fighting over to the South Vietnamese. Dean Rusk then proposed that the president unilaterally halt the bombing of North Vietnam north of the 20th parallel and call for negotiations. It was assumed that the North Vietnamese would denounce the project, which would cast the onus upon them and "thus free our hand after a short period...putting the monkey firmly upon Hanoi's back for what was to follow."[170]

Lyndon Johnson was depressed and despondent at the course of recent events. The New York Times article had been released just two days before the United States Democratic Party's New Hampshire Primary, where the President suffered a unexpected setback in the election, finishing barely ahead of United States Senator Eugene McCarthy. Soon afterward, Senator Robert F. Kennedy announced he would join the contest for the Democratic nomination, further emphasizing the plummeting support for Johnson's administration in the wake of Tet. On 31 March, the President announced a unilateral bombing halt during a television address and then stunned the nation by declining to run for a second term. Surprisingly, on 3 April, Hanoi announced that it would conduct negotiations, which were scheduled to begin on 13 May in Paris.

On 9 June President Johnson replaced William Westmoreland as commander of MACV with General Creighton W. Abrams. Although the decision had been made in December 1967 and Westmoreland was made Army Chief of Staff, many saw his relief as punishment for the entire Tet debacle.[171] Abrams new strategy was quickly demonstrated by the closure of the "strategic" Khe Sanh base and the ending of the multi-division "search and destroy" operations. Also over were discussions of victory over North Vietnam. Abrams' new "One War" strategy centered the American effort on the the takeover of the fighting (through Vietnamization), the pacification of the countryside, and the destruction of communist logistics.[172] The Americans were leaving, it was just a matter of time.

Notes

- ^ Hoang Ngoc Lung, The General Offensives McLean VA: General Research Corporation, 1978, p. 8.

- ^ The ARVN estimated communist forces at 323,000, including 130,000 regulars and 160,000 guerrillas. Hoang, p. 10. MACV estimated that strength at 330,000. The CIA and the U.S. State Department concluded that the communist force level lay somewhere between 435,000 and 595,000. Clark Dougan & Stephen Weiss, Nineteen Sixty-Eight, Boston: Boston Publishing Compnay, 1983, p. 184.

- ^ Includes casualties incurred during the "Border Battles", Tet Mau Than, and the second and third phases of the offensive.

- ^ Military offensives are generally known by the titles applied to them by the attacking party. In the West, however, this convention was abandoned during the Cold War. The General Offensive, General Uprising also took place during the early stages of the media revolution which, for the first time, allowed close to real-time depiction of historic events to the public. This helps explain why both historians and the public have always referred to the Tet operations by their Western title.

- ^ Dougan and Weiss, p. 8.

- ^ Although General Westmoreland never uttered this phrase (it was coined by General Henri Navarre during the First Indochina War), it came into general paralance during the Vietnam War and has become a catchphrase for similar situations.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, pgs. 22 & 23.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 22.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 22.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 23.

- ^ (CIA Center for the Study of Intelligence)

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 23. This Order of Battle controversy resurfaced in 1982, when Westmoreland filed a lawsuit against CBS News after the airing of its program, The Uncounted Enemy: A Vietnam Deception, which aired had on 23 January 1982.

- ^ Those in the administration and the military who urged a change in strategy included: Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara; Nicholas Katzenbach; William Bundy; Ambassador to South Vietnam Henry Cabot Lodge; General Creighton W. Abrams, deputy commander of MACV; and Lieutenant General Frederick C. Weyand, commander of II Field Force, Vietnam. Lewis Sorley, A Better War. New York: Harvest Books, 1999, p. 6. Throughout 1967, the Pentagon Papers claimed, Johnson had discounted any "negative analysis" of U.S. strategy by the CIA and the Pentagon offices of International Security Affairs and System Analysis and had instead "siezed upon optimistic reports from General Westmoreland." Neil Sheehan, et al. The Pentagon Papers as Reported by the New York Times. New York: Ballentine, 1971, p. 592.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 68.

- ^ Stanley Karnow, Vietnam. New York: Viking, 1083, p. 545 & 546.

- ^ Karnow, p. 546.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 66.

- ^ Schmitz, p. 56.

- ^ Schmitz, p. 58.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 66.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 69.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 67.

- ^ Karnow, p. 514.

- ^ Elliot, The Vietnamese War, vol. 2, p. 1055.

- ^ Lien Hang T. Nguyen, The War Politburo in Journal of Vietnamese Studies. Vol. 1, Numbers 1 & 2, p. 4.

- ^ Nguyen, p. 20.

- ^ Edward Doyle, Samuel Lipsman, & Terrence Maitland, The North. Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1986, p. 55.

- ^ Nguyen, p. 22.

- ^ Contrary to Western belief, Ho Chi Minh had been sidelined politically since 1963 and took little part in the day-to-day policy decisions of the Politburo or Secretariat. Nguyen, p. 30.

- ^ The publication of Giap's Big Victory, Great Task should be viewed in this context. Doyle, Lipsman, & Maitland, p. 56.

- ^ Hoang, p. 16.

- ^ Nguyen, pgs. 18-20.

- ^ Nguyen, p. 24.

- ^ Nguyen, p. 27.

- ^ Hoang, p. 24.

- ^ Nguyen, p. 24.

- ^ Doyle, Lipsman, & Maitland, p. 56.

- ^ The exact nature of Thanh's demise is not known at present. The general consensus is that he was wounded, taken to Hanoi to recover, and then died of a heart attack. See Nguyen, fn. 147.

- ^ Nguyen, p. 34. Also see Doyle, Lipsman, & Maitland, p. 56.

- ^ Marc Gilbert and James Wells Hau Nghia Part 3: "Out of Blind Xenophobia", 2005. http://grunt.space.swri.edu/gilbert3.htm

- ^ Doyle, Lipsman, & Maitland, pgs. 58 & 59.

- ^ ?

- ^ Hoang, p. 26.

- ^ Karnow, p. 537.

- ^ Tran Van Tra, Tet in Jayne S. Werner and Luu Doan Huynh, eds., The Vietnam War. Armonk NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1993, p. 40.

- ^ Military History Institute of Vietnam, Victory in Vietnam,, Lawrence KS: University Press of Kansas, 2005, p. 208. See also Doyle, Lipsman, & Maitland, The North, p. 46.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 10.

- ^ Hoang, p. 10.

- ^ Steven Hayward, The Tet Offensive: Dialogues, April 2004. http://www.ashbrook.org/publicat/dialogue/hayward-tet.html#2r

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 11.

- ^ Hoang, p. 39.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 11.

- ^ Moyars Shore, The Battle of Khe Sanh. U.S. Marine Corps Historical Branch, 1969, p. 17.

- ^ John Morocco, Thunder from Above. Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1984, pgs. 174-176.

- ^ Hoang, p. 9.

- ^ Hoang, p. 9.

- ^ Terrence Maitland & Peter McInerney, A Contafion of War. Boston: Boston Publishing Company, 1983, pgs. 160-183.

- ^ Dave R. Palmer, Summons of the Trumpet. New York: Ballentine, 1978, pgs. 229 & 233.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 8.

- ^ Palmer, p. 235.

- ^ Shelby L. Stanton, Rise and Fall of an American Army. New York: Dell, 1985, p. 195.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 124.

- ^ Willbanks, The Tet Offensive New Haven CT: Yale University Press, p. 7.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 12.

- ^ Hoang, p. 35.

- ^ Samuel Zaffiri, Westmoreland. New York,: William Morrow, 1994, p. 280.

- ^ Zaffiri, p. 280.

- ^ The first attacks may have been launched prematurely due to confusion over a changeover in the calender date by communist units. Hanoi had arbitrarily forwarded the date of the holiday in order to allow its citizens respite from the retaliatory airstrikes that were sure to follow the offensive. Whether this was connected to the mixup over the launch date is unknown. All eight of the attacks were controlled by the North Vietnamese headquarters of Military Region 5.

- ^ William C. Westmoreland, A Soldier Reports. New York: Doubleday, 1976, p. 323.

- ^ Stanton, p. 209.

- ^ Westmoreland, p. 328. Palmer gave a figure of 70,000, p. 238.

- ^ Westmoreland, p. 328.

- ^ Westmoreland, p. 332.

- ^ Karnow, p. 549.

- ^ Zaffiri, p. 283.

- ^ Peter Braestrup, Big Story. New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 1983, p. 108.

- ^ Andrew Wiest, The Vietnam War, 1956-1975. London: Osprey Publishing, 2002, p. 41

- ^ Stanton, p. 215. For a detailed description of U.S. participation in the defense see Keith W. Nolan, The Battle of Saigon, Tet 1968. New York: Pocket Books, 1996.

- ^ Westmoreland, p. 326.

- ^ Hoang, p.?

- ^ The South Vietnamese Ambassador, Bui Diem, stated that such images "crystalized the war's brutality without providing a context within which to understand the events they depicted." Bui Diem, In the Jaws of History. Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press, 1999. There was little mention in the American media of the hundreds of South Vietnamese executed in Saigon by the communists.

- ^ Hoang, p. 40.

- ^ Willbanks, p. 32.

- ^ Westmoreland, p. 332.

- ^ Palmer, p. 245. These units included the 12th NLF Battalion and the Hue City NLF Sapper Battalion.

- ^ Jack Schulimson, et al, 1968. Washington DC: History and Museums Division, United States Marine Corps, 1997, p. 175. For a detailed description of U.S. participation in the battle see Keith W. Nolan, Battle for Hue, Tet 1968. Novato CA: Presidio Press, 1983.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 28.

- ^ Schulimson, p. 213.

- ^ Schulimson, p. 213. A communist document later captured by the ARVN stated that 1,042 troops had been killed in the city proper and that several times that number had been wounded. Hoang, p. 84.

- ^ Schulimson, p. 213.

- ^ Schulimson, p. 216.

- ^ Dougan & Weiss, p. 35. This was the version given in Douglas Pike's The Viet Cong Strategy of Terror, published by the U.S. Mission in 1970.

- ^ Don Oberdorfer, Tet!. New York: Doubleday, 1971, pgs. 232 & 233.

- ^ Bui Tin, From Enemy to Friend. Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press, 2002, p. 67.

- ^ Hoang, p. 82.

- ^ Karnow, pg. 555, John Prados, The Blood Road, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1998, p. 242.

- ^ Westmoreland, pgs. 339 & 340.

- ^ Westmoreland, p. 311.

- ^ Robert Pisor, The End of the Line. New York: Ballentine, 1982, p. 61.

- ^ John Prados & Ray W. Stubbe, Valley of Decision. Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991, p. 297