World War I

"War to end all wars" redirects here. For the Yngwie Malmsteen album, see War to End All Wars (album).

World War I, also known as the First World War, the Great War and the War To End All Wars, was a global military conflict which took place primarily in Europe from 1914 to 1918. Over 40 million casualties resulted, including approximately 20 million military and civilian deaths. The conflict had a decisive impact on the history of the 20th century.

The Entente Powers, led by France, Russia, the United Kingdom and its colonies and dominions, and later Italy (from 1915) and the United States (from 1917), defeated the Central Powers, led by the Austro-Hungarian, German, and Ottoman Empires. Russia withdrew from the war after the revolution in 1917.

The fighting that took place along the Western Front occurred along a system of trenches, breastworks, and fortifications separated by an area known as no man's land.[2] These fortifications stretched 475 miles (more than 600 kilometres)[2] and defined the war for many. On the Eastern Front, the vast eastern plains and limited rail network prevented a trench warfare stalemate, though the scale of the conflict was just as large as on the Western Front. The Middle Eastern Front and the Italian Front also saw heavy fighting, while hostilities also occurred at sea, and for the first time, in the air.

The war caused the disintegration of four empires: the Austro-Hungarian, German, Ottoman and Russian. Germany lost its colonial empire and states such as Czechoslovakia, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Yugoslavia gained independence. The cost of waging the war set the stage for the breakup of the British Empire as well and left France devastated for more than a generation.

World War I marked the end of the world order which had existed after the Napoleonic Wars, and was an important factor in the outbreak of World War II.

Causes

On the 28 June 1914, Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb student, killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, in Sarajevo. Princip was a member of Young Bosnia, a group whose aims included the unification of the South Slavs and independence from Austria-Hungary. The assassination in Sarajevo set into motion a series of fast-moving events that eventually escalated into full-scale war. Austria-Hungary demanded action by Serbia to punish those responsible, and when Austria-Hungary deemed Serbia had not complied, declared war. Major European powers were at war within weeks because of overlapping agreements for collective defense and the complex nature of international alliances.

Arms race

The naval race between Britain and Germany was intensified by the 1906 launch of HMS Dreadnought —a revolutionary craft whose size and power rendered previous battleships obsolete. Britain also maintained a large naval lead in other areas particularly over Germany and Italy. Paul Kennedy pointed out both nations believed Alfred Thayer Mahan's thesis of command of the sea as vital to great nation status; experience with guerre de course would prove Mahan wrong.

David Stevenson described the arms race as "a self-reinforcing cycle of heightened military preparedness." David Herrmann viewed the shipbuilding rivalry as part of a general movement in the direction of war. Niall Ferguson, however, argued Britain's ability to maintain an overall lead signified this was not a factor in the oncoming conflict.

The cost of the arms race was felt in both Britain and Germany. The total arms spending by the six Great Powers (Britain, Germany, France, Russia, Austria-Hungary and Italy) increased by 50% between 1908 and 1913.[3]

Plans, distrust and mobilization

Closely related is the thesis adopted by many political scientists that the mobilization plans of Germany, France and Russia automatically escalated the conflict. Fritz Fischer emphasized the inherently aggressive nature of the Schlieffen Plan, which outlined a two-front strategy. Fighting on two fronts meant Germany had to eliminate one opponent quickly before taking on the other. It called for a strong right flank attack, to seize Belgium and cripple the French army by pre-empting its mobilization. After the attack, the German army would rush east by railroad and quickly destroy the slowly mobilizing Russian forces.

France's Plan XVII envisioned a quick thrust into the Ruhr Valley, Germany’s industrial heartland, which would in theory cripple Germany's ability to wage a modern war.

Russia's Plan XIX foresaw a mobilization of its armies against both Austria-Hungary and Germany.

All three plans created an atmosphere in which speed was one of the determining factors for victory. Elaborate timetables were prepared; once mobilization had begun, there was little possibility of turning back. Diplomatic delays and poor communications exacerbated the problems.

Also, the plans of France, Germany and Russia were all biased toward the offensive, in clear conflict with the improvements of defensive firepower and entrenchment.[4]

Militarism and autocracy

President Woodrow Wilson of the United States and others blamed the war on militarism.[5] Some argued that aristocrats and military élites had too much power in countries such as Germany, Russia, and Austria-Hungary. War was thus a consequence of their desire for military power and disdain for democracy. This theme figured prominently in anti-German propaganda. Consequently, supporters of this theory called for the abdication of rulers such as Kaiser Wilhelm II, as well as an end to aristocracy and militarism in general. This platform provided some justification for the American entry into the war when the Russian Empire surrendered in 1917.

Wilson hoped the League of Nations and disarmament would secure a lasting peace. He also acknowledged that variations of militarism, in his opinion, existed within the British and French Empires.

There was some validity to this view, as the Allies consisted of Great Britain and France, both democracies, fighting the Central Powers, which included Germany, Austro-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire. Russia, one of the Allied Powers, was an empire until 1917, but it was opposed to the subjugation of Slavic peoples by Austro-Hungary. Against this backdrop, the view of the war as one of democracy versus dictatorship initially had some validity, but lost credibility as the conflict dragged on.

Balance of Power

One of the goals of the foreign policies of the Great Powers in the pre-war years was to maintain the 'Balance of Power' in Europe. This evolved into an elaborate network of secret and public alliances and agreements. For example, after the Franco-Prussian war (1870–71), Britain seemed to favor a strong Germany, as it helped to balance its traditional enemy, France. After Germany began its naval construction plans to rival that of Britain, this stance shifted. France, looking for an ally to balance the threat created by Germany, found it in Russia. Austria-Hungary, facing a threat from Russia, sought support from Germany.

When the Great War broke out, these treaties only partially determined who entered the war on which side. Britain had no treaties with France or Russia, but entered the war on their side. Italy had a treaty with both Austria-Hungary and Germany, yet did not enter the war with them; Italy later sided with the Allies. Perhaps the most significant treaty of all was the initially defensive pact between Germany and Austria-Hungary, which Germany in 1909 extended by declaring that Germany was bound to stand with Austria-Hungary even if it had started the war.[6]

Economic imperialism

Vladimir Lenin asserted that imperialism was responsible for the war. He drew upon the economic theories of Karl Marx and English economist John A. Hobson, who predicted that unlimited competition for expanding markets would lead to a global conflict.[7] This argument was popular in the wake of the war and assisted in the rise of Communism. Lenin argued that the banking interests of various capitalist-imperialist powers orchestrated the war.[8]

Trade barriers

Cordell Hull, American Secretary of State under Franklin Roosevelt, believed that trade barriers were the root cause of both World War I and World War II. In 1944, he helped design the Bretton Woods Agreements to reduce trade barriers and eliminate what he saw as the cause of the conflicts.

Ethnic and political rivalries

A Balkan war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia was considered inevitable, as Austria-Hungary’s influence waned and the Pan-Slavic movement grew. The rise of ethnic nationalism coincided with the growth of Serbia, where anti-Austrian sentiment was perhaps most fervent. Austria-Hungary had occupied the former Ottoman province of Bosnia-Herzegovina, which had a large Serb population, in 1878. It was formally annexed by Austria-Hungary in 1908. Increasing nationalist sentiment also coincided with the decline of the Ottoman Empire. Russia supported the Pan-Slavic movement, motivated by ethnic and religious loyalties and a rivalry with Austria dating back to the Crimean War. Recent events such as the failed Russian-Austrian treaty and a century-old dream of a warm water port also motivated St. Petersburg.[9]

Myriad other geopolitical motivations existed elsewhere as well, for example France's loss of Alsace and Lorraine in the Franco-Prussian War helped create a sentiment of irredentist revanchism in that country. France eventually allied itself with Russia, creating the likelihood of a two-front war for Germany.

July crisis and declarations of war

The Austro-Hungarian government used the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand as a pretext to deal with the Serbian question, supported by Germany. On 23 July 1914, an ultimatum was sent to Serbia with demands so extreme that it was rejected. The Serbians, relying on support from Russia, instead ordered mobilization. In response to this, Austria-Hungary issued a declaration of war on 28 July. Initially, Russia ordered partial mobilization, directed at the Austrian frontier. On 31 July, after the Russian General Staff informed the Czar that partial mobilization was logistically impossible, a full mobilization was ordered. The Schlieffen Plan, which relied on a quick strike against France, could not afford to allow the Russians to mobilize without launching an attack. Thus, the Germans declared war against Russia on 1 August and on France two days later. Next, Germany violated Belgium's neutrality by the German advance through it to Paris, and this brought the British Empire into the war. With this, five of the six European powers were now involved in the largest continental European conflict since the Napoleonic Wars.[10]

Chronology

Opening hostilities

Confusion among the Central Powers

The strategy of the Central Powers suffered from miscommunication. Germany had promised to support Austria-Hungary’s invasion of Serbia, but interpretations of what this meant differed. Austro-Hungarian leaders believed Germany would cover its northern flank against Russia. Germany, however, envisioned Austria-Hungary directing the majority of its troops against Russia, while Germany dealt with France. This confusion forced the Austro-Hungarian Army to divide its forces between the Russian and Serbian fronts.

African campaigns

Some of the first clashes of the war involved British, French and German colonial forces in Africa. On 7 August, French and British troops invaded the German protectorate of Togoland. On 10 August German forces in South-West Africa attacked South Africa; sporadic and fierce fighting continued for the remainder of the war.

Serbian campaign

The Serbian army fought the Battle of Cer against the invading Austrians, beginning on 12 August, occupying defensive positions on the south side of the Drina and Sava rivers. Over the next two weeks Austrian attacks were thrown back with heavy losses, which marked the first major Allied victory of the war and dashed Austrian hopes of a swift victory. As a result, Austria had to keep sizable forces on the Serbian front, weakening their efforts against Russia. Serbian troops then defeated Austro-Hungarian forces at the Battle of Kolubara, leading to 240,000 Austro-Hungarian casualties. The Serbian Army lost 170,000 troops.

German forces in Belgium and France

Initially, the Germans had great success in the Battle of the Frontiers (14 August – 24 August). Russia, however, attacked in East Prussia and diverted German forces intended for the Western Front. Germany defeated Russia in a series of battles collectively known as the First Battle of Tannenberg (17 August – 2 September), but this diversion exacerbated problems of insufficient speed of advance from rail-heads not foreseen by the German General Staff. Originally, the Schlieffen Plan called for the right flank of the German advance to pass to the west of Paris. However, the capacity and low speed of horse-drawn transport hampered the German supply train, allowing French and British forces to finally halt the German advance east of Paris at the First Battle of the Marne (5 September – 12 September), thereby denying the Central Powers a quick victory and forcing them to fight a war on two fronts. The German army had fought its way into a good defensive position inside France and had permanently incapacitated 230,000 more French and British troops than it had lost itself. Despite this, communications problems and questionable command decisions cost Germany the chance for an early victory.

Asia and the Pacific

New Zealand occupied German Samoa (later Western Samoa) on 30 August. On 11 September the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force landed on the island of Neu Pommern (later New Britain), which formed part of German New Guinea. Japan seized Germany’s Micronesian colonies and after Battle of Tsingtao, the German coaling port of Qingdao, in the Chinese Shandong peninsula. Within a few months, the Allied forces had seized all the German territories in the Pacific.

Early stages

Trench warfare begins

Military tactics before World War I had failed to keep pace with advances in technology. It demanded the building of impressive defence systems, which out-of-date tactics could not break through for most of the war. Barbed wire was a significant hindrance to massed infantry advances. Artillery, vastly more lethal than in the 1870s, coupled with machine guns, made crossing open ground very difficult. The Germans introduced poison gas; it soon became used by both sides, though it never proved decisive in winning a battle. Its effects were brutal, however, causing slow and painful death, and poison gas became one of the most-feared and best-remembered horrors of the war. Commanders on both sides failed to develop tactics for breaking through entrenched positions without heavy casualties. In time, however, technology began also to yield new offensive weapons, such as the tank. Britain and France were its primary users; the Germans employed captured Allied tanks and small numbers of their own design.

After the First Battle of the Marne, both Entente and German forces began a series of outflanking maneuvers, in the so-called 'Race to the Sea'. Britain and France soon found themselves facing entrenched German forces from Lorraine to Belgium's Flemish coast. Britain and France sought to take the offensive, while Germany defended the occupied territories; consequentially, German trenches were generally much better constructed than those of their enemy. Anglo-French trenches were only intended to be 'temporary' before their forces broke through German defenses. Both sides attempted to break the stalemate using scientific and technological advances. In April 1915, the Germans used chlorine gas for the first time (in violation of the Hague Convention), opening a 6 kilometres (4 mi) hole in the Allied lines when British and French colonial troops retreated. Canadian soldiers closed the breach at the Second Battle of Ypres. At the Third Battle of Ypres, Canadian forces took the village of Passchendaele.

On 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme, the British Army endured the bloodiest day in its history, suffering 57,470 casualties and 19,240 dead. Most of the casualties occurred in the first hour of the attack. The entire offensive cost the British Army almost half a million dead.

Neither side proved able to deliver a decisive blow for the next two years, though protracted German action at Verdun throughout 1916, combined with the Entente’s failure at the Somme, brought the exhausted French army to the brink of collapse. Futile attempts at frontal assault, a rigid adherence to an ineffectual method, came at a high price for both the British and the French poilu (infantry) and led to widespread mutinies, especially during the Nivelle Offensive.

Throughout 1915–17, the British Empire and France suffered more casualties than Germany, due both to the strategic and tactical stances chosen by the sides. At the strategic level, while the Germans only mounted a single main offensive at Verdun, the Allies made several attempts to break through German lines. At the tactical level, the German defensive doctrine was well suited for trench warfare, with a relatively lightly defended "sacrificial" forward position, and a more powerful main position from which an immediate and powerful counter-offensive could be launched. This combination usually was effective in pushing out attackers at a relatively low cost to the Germans. In absolute terms, of course, the cost in lives of men for both attack and defense was astounding.

Around 800,000 soldiers from the British Empire were on the Western Front at any one time. 1,000 battalions, occupying sectors of the line from the North Sea to the Orne River, operated on a month-long four-stage rotation system, unless an offensive was underway. The front contained over 9,600 kilometres (5,965 mi) of trenches. Each battalion held its sector for about a week before moving back to support lines and then further back to the reserve lines before a week out-of-line, often in the Poperinge or Amiens areas.

In the Battle of Arras under British command during the 1917 campaign, the only military success was the capture of Vimy Ridge by Canadian forces under Sir Arthur Currie and Julian Byng. It provided the allies with a great military advantage and had a lasting impact on the war. Vimy is considered by many historians to be one of the founding myths of Canada.

Naval war

At the start of the war, the German Empire had cruisers scattered across the globe, some of which were subsequently used to attack Allied merchant shipping. The British Royal Navy systematically hunted them down, though not without some embarrassment from its inability to protect allied shipping. For example, the German detached light cruiser Emden, part of the East-Asia squadron stationed at Tsingtao, seized or destroyed 15 merchantmen, as well as sinking a Russian cruiser and a French destroyer. However, the bulk of the German East-Asia squadron—consisting of the armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, light cruisers Nürnberg and Leipzig and two transport ships—did not have orders to raid shipping and was instead underway to Germany when it encountered elements of the British fleet. The German flotilla, along with Dresden, sank two armoured cruisers at the Battle of Coronel, but was almost completely destroyed at the Battle of the Falkland Islands in December 1914, with only Dresden escaping.[11]

Soon after the outbreak of hostilities, Britain initiated a naval blockade of Germany. The strategy proved effective, cutting off vital military and civilian supplies, although this blockade violated generally accepted international law codified by several international agreements of the past two centuries.[citation needed] A blockade of stationed ships within a three mile (5 km) radius was considered legitimate,[citation needed] however Britain mined international waters to prevent any ships from entering entire sections of ocean, causing danger to even neutral ships.[citation needed] Since there was limited response to this tactic, Germany expected a similar response to its unrestricted submarine warfare.[citation needed]

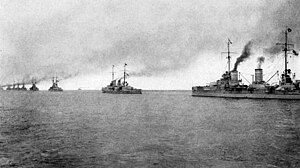

The 1916 Battle of Jutland (German: Skagerrakschlacht, or "Battle of the Skagerrak") developed into the largest naval battle of the war, the only full-scale clash of battleships during the war. It took place on 31 May–1 June, 1916, in the North Sea off Jutland. The Kaiserliche Marine's High Seas Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer, squared off against the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet, led by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe. The engagement was a standoff, as the Germans, outmaneuvered by the larger British fleet, managed to escape and inflicted more damage to the British fleet than they received. Strategically, however, the British asserted their control of the sea, and the bulk of the German surface fleet remained confined to port for the duration of the war.

German U-boats attempted to cut the supply lines between North America and Britain.[citation needed] The nature of submarine warfare meant that attacks often came without warning, giving the crews of the merchant ships little hope of survival.[citation needed] The United States launched a protest, and Germany modified its rules of engagement. After the infamous sinking of the passenger ship RMS Lusitania in 1915, Germany promised not to target passenger liners, while Britain armed its merchant ships. Finally, in early 1917 Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, realizing the Americans would eventually enter the war [citation needed]. Germany sought to strangle Allied sea lanes before the U.S. could transport a large army overseas.

The U-boat threat lessened in 1917, when merchant ships entered convoys escorted by destroyers. This tactic made it difficult for U-boats to find targets, which significantly lessened losses; after the introduction of hydrophone and depth charges, accompanying destroyers might actually attack a submerged submarine with some hope of success. The convoy system slowed the flow of supplies, since ships had to wait as convoys were assembled. The solution to the delays was a massive program to build new freighters. Troop ships were too fast for the submarines and did not travel the North Atlantic in convoys.[citation needed]

The First World War also saw the first use of aircraft carriers in combat, with HMS Furious launching Sopwith Camels in a successful raid against the Zeppelin hangars at Tondern in July 1918, as well as blimps for antisubmarine patrol.[12]

Southern theatres

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers in the war, the secret Ottoman-German Alliance having been signed in August 1914. It threatened Russia’s Caucasian territories and Britain’s communications with India via the Suez Canal. The British and French opened overseas fronts with the Gallipoli (1915) and Mesopotamian campaigns. In Gallipoli, the Turks successfully repelled the British, French and Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs). In Mesopotamia, by contrast, after the disastrous Siege of Kut (1915–16), British Imperial forces reorganised and captured Baghdad in March 1917. Further to the west, in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign, initial British setbacks were overcome when Jerusalem was captured in December 1917. The Egyptian Expeditionary Force, under Field Marshal Edmund Allenby, broke the Ottoman forces at the Battle of Megiddo in September 1918.

Russian armies generally had the best of it in the Caucasus. Vice-Generalissimo Enver Pasha, supreme commander of the Turkish armed forces, was ambitious and dreamed of conquering central Asia. He was, however, a poor commander.[citation needed] He launched an offensive against the Russians in the Caucasus in December 1914 with 100,000 troops; insisting on a frontal attack against mountainous Russian positions in winter, he lost 86% of his force at the Battle of Sarikamis.[citation needed]

The Russian commander from 1915 to 1916, General Yudenich, drove the Turks out of most of the southern Caucasus with a string of victories.[citation needed]

In 1917, Russian Grand Duke Nicholas assumed command of the Caucasus front. Nicholas planned a railway from Russian Georgia to the conquered territories, so that fresh supplies could be brought up for a new offensive in 1917. However, in March 1917, (February in the pre-revolutionary Russian calendar), the Czar was overthrown in the February Revolution and the Russian Caucasus Army began to fall apart. In this situation, the army corps of Armenian volunteer units realigned themselves under the command of General Tovmas Nazarbekian, with Dro as a civilian commissioner of the Administration for Western Armenia. The front line had three main divisions: Movses Silikyan, Andranik and Mikhail Areshian. Another regular unit was under Colonel Korganian. There were Armenian partisan guerrilla detachments (more than 40,000[13]) accompanying these main units.

The Arab Revolt was a major cause of the Ottoman Empire's defeat. The revolts started with the Battle of Mecca by Sherif Hussain of Mecca with the help of Britain in June 1916, and ended with the Ottoman surrender of Damascus. Fakhri Pasha the Ottoman commander of Medina showed stubborn resistance for over two and half years during the Siege of Medina.

Along the border of Italian Libya and British Egypt, the Senussi tribe, incited and armed by the Turks, waged a small-scale guerilla war against Allied troops. According to Martin Gilbert's The First World War, the British were forced to dispatch 12,000 troops to deal with the Senussi. Their rebellion was finally crushed in mid-1916.

Italian participation

Italy had been allied with the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires since 1882 as part of the Triple Alliance. However, the nation had its own designs on Austrian territory in Trentino, Istria and Dalmatia. Rome had a secret 1902 pact with France, effectively nullifying its alliance.[14] At the start of hostilities, Italy refused to commit troops, arguing that the Triple Alliance was defensive in nature, and that Austria-Hungary was an aggressor. The Austro-Hungarian government began negotiations to secure Italian neutrality, offering the French colony of Tunisia in return. However, Italy then joined the Entente in April 1915 and declared war on Austria-Hungary in May. Fifteen months later, it declared war on Germany.

Militarily, the Italians had numerical superiority. This advantage, however, was lost, not only because of the difficult terrain in which fighting took place, but also because of the strategies and tactics employed. Generalissimo Luigi Cadorna insisted on attacking the Isonzo front. Cadorna, a staunch proponent of the frontal assault, had dreams of breaking into the Slovenian plateau, taking Ljubljana and threatening Vienna. It was a Napoleonic plan, which had no realistic chance of success in an age of barbed wire, machine guns, and indirect artillery fire, combined with hilly and mountainous terrain. Cadorna unleashed eleven offensives (Battles of the Isonzo) with total disregard for his men's lives. The Italians also went on the offensive to relieve pressure on other Allied fronts. On the Trentino front, the Austro-Hungarians took advantage of the mountainous terrain, which favoured the defender. After an initial strategic retreat, the front remained largely unchanged, while Austrian Kaiserschützen and Standschützen and Italian Alpini engaged in bitter hand-to-hand combat throughout the summer. The Austro-Hungarians counter-attacked in the Altopiano of Asiago, towards Verona and Padua, in the spring of 1916 (Strafexpedition), but made little progress.

Beginning in 1915, the Italians mounted eleven offensives along the Isonzo River, north-east of Trieste. All eleven offensives were repelled by the Austro-Hungarians, who held the higher ground. In the summer of 1916, the Italians captured the town of Gorizia. After this minor victory, the front remained static for over a year, despite several Italian offensives. In the autumn of 1917, thanks to the improving situation on the Eastern front, the Austrians received large numbers of reinforcements, including German Stormtroopers and the elite Alpenkorps. The Central Powers launched a crushing offensive on 26 October 1917, spearheaded by the Germans. They achieved a victory at Caporetto. The Italian army was routed and retreated more than 100 km (60 miles). They were able to reorganise and stabilize the front at the Piave River. In 1918, the Austro-Hungarians repeatedly failed to break through, in a series of battles on the Asiago Plateau, finally being decisively defeated in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto in October of that year. Austria-Hungary surrendered in early November 1918.

War in the Balkans

Faced with Russia, Austria-Hungary could spare only one third of its army to attack Serbia. After suffering heavy losses, the Austrians briefly occupied the Serbian capital, Belgrade. Serbian counterattacks, however, succeeded in driving them from the country by the end of 1914. For the first ten months of 1915, Austria-Hungary used most of its military reserves to fight Italy. German and Austro-Hungarian diplomats, however, scored a coup by convincing Bulgaria to join in attacking Serbia. The Austro-Hungarian provinces of Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia provided troops for Austria-Hungary, invading Serbia as well as fighting Russia and Italy. Montenegro allied itself with Serbia.

Serbia was conquered in a little more than a month. The attack began in October, when the Central Powers launched an offensive from the north; four days later the Bulgarians joined the attack from the east. The Serbian army, fighting on two fronts and facing certain defeat, retreated into Albania, halting only once, to make a stand against the Bulgarians. The Serbs suffered defeat near modern day Gnjilane in Kosovo, forces being evacuated by ship to Greece.

In late 1915, a Franco-British force landed at Salonica in Greece, to offer assistance and to pressure the government to declare war against the Central Powers. Unfortunately for the Allies, the pro-German King Constantine I dismissed the pro-Allied government of Eleftherios Venizelos, before the allied expeditionary force could arrive.

The Salonica Front proved static; it was joked that Salonica was the largest German prisoner of war camp of the war.[citation needed] Only at the end of the conflict were the Entente powers able to break through, which was after most of the German and Austro-Hungarian troops had been withdrawn. The Bulgarians suffered their only defeat of the war, at the battle of Dobro Pole, but days later, they decisively defeated British and Greek forces at the battle of Doiran, avoiding occupation. Bulgaria signed an armistice on 29 September, 1918.

Fighting in India

Although the conflict in India cannot be explicitly said to have been a part of the First World War, it can certainly be said to have been significant in terms of the wider strategic context. The British attempt to subjugate the tribal leaders who had rebelled against their British overlords drew away much needed troops from other theaters, in particular, of course, the Western Front, where the real decisive victory would be made.

The reason why some Indian and Afghani tribes rose up simply came down to years of discontent which erupted, probably not coincidentally, during the First World War. It is likely that the tribal leaders were aware that Britain would not be able to field the required men, in terms of either number or quality. They underestimated, however, the strategic importance placed on India by the British; despite being located far away from the epicenter of the conflict, it provided a bounty of men for the fronts. Its produce was also needed for the British war effort and many trade routes running to other profitable areas of the Empire ran through India. Therefore, although the British were not able to send the men that they wanted, they were able to send enough to resist the revolt of the tribesmen through a gradual but effective counter-guerilla war. The fighting continued into 1919 and in some areas lasted even longer. See also Third Anglo-Afghan War.

Eastern Front

Initial actions

While the Western Front had reached stalemate, the war continued in the East. Initial Russian plans called for simultaneous invasions of Austrian Galicia and German East Prussia. Although Russia's initial advance into Galicia was largely successful, they were driven back from East Prussia by Hindenburg and Ludendorff at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes in August and September 1914. Russia's less developed industrial base and ineffective military leadership was instrumental in the events that unfolded. By the spring of 1915, the Russians had retreated into Galicia, and in May the Central Powers achieved a remarkable breakthrough on Poland's southern frontiers. On 5 August they captured Warsaw and forced the Russians to withdraw from Poland. This became known as the "Great Retreat" in Russia and the "Great Advance" in Germany.

Ukrainian oppression

During World War I the western Ukrainian people were situated between Austria-Hungary and Russia. Ukrainian villages were regularly destroyed in the crossfire. Ukrainians could be found participating on both sides of the conflict (though most sided with Austria-Hungary with the intention of ending the war on the Eastern Front and creating an independent Ukrainian state). However, Ukrainians in Galicia who were suspected of being sympathetic to Russian interests were repressed by Austro-Hungarian authorities. Over twenty thousand supporters of Russia were arrested and placed in Austrian concentration camps in Talerhof, Styria and in Terezín fortress (now in the Czech Republic).

With the collapse of the Russian and Austrian empires following World War I and the Russian Revolution of 1917, Ukrainian national movement for self-determination emerged again. During 1917–20 several separate Ukrainian states briefly emerged: the Central Rada, the Hetmanate, the Directorate, the Ukrainian People's Republic and the West Ukrainian People's Republic. However, with the defeat of the latter in the Polish-Ukrainian War and the failure of the Polish Kiev Offensive (1920) of the Polish-Soviet War, the Peace of Riga concluded in March 1921 between Poland and Bolsheviks left Ukraine divided again. The western part of Galicia had been incorporated into newly organized Second Polish Republic, incorporating territory claimed or controlled by the ephemeral Komancza Republic and the Lemko-Rusyn Republic. The larger, central and eastern part, established as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in March 1919, later became a constituent republic of the Soviet Union, when it was formed in December 1922.

Russian Revolution

Dissatisfaction with the Russian government's conduct of the war grew, despite the success of the June 1916 Brusilov offensive in eastern Galicia. The success was undermined by the reluctance of other generals to commit their forces to support the victory. Allied and Russian forces revived only temporarily with Romania's entry into the war on 27 August. German forces came to the aid of embattled Austrian units in Transylvania and Bucharest fell to the Central Powers on 6 December. Meanwhile, unrest grew in Russia, as the Tsar remained at the front. Empress Alexandra's increasingly incompetent rule drew protests and resulted in the murder of her favourite, Rasputin, at the end of 1916.

In March 1917, demonstrations in St Petersburg culminated in the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II and the appointment of a weak Provisional Government. It shared power with the socialists of the Petrograd Soviet. This arrangement led to confusion and chaos both at the front and at home. The army became increasingly ineffective.

The war and the government became more and more unpopular. Discontent led to a rise in popularity of the Bolshevik party, led by Vladimir Lenin. He promised to pull Russia out of the war and was able to gain power. The triumph of the Bolsheviks in November was followed in December by an armistice and negotiations with Germany. At first, the Bolsheviks refused to agree to the harsh German terms. But when Germany resumed the war and marched with impunity across Ukraine, the new government acceded to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on 3 March, 1918. It took Russia out of the war and ceded vast territories, including Finland, the Baltic provinces, parts of Poland and Ukraine to the Central Powers.

The publication by the new Bolshevik government of the secret treaties signed by the Tsar was hailed across the world, either as a great step forward for the respect of the will of the people, or as a dreadful catastrophe which could destabilise the world. The existence of a new type of government in Russia led to the reinforcement in many countries of Communist parties.

After the Russians dropped out of the war, the Entente no longer existed. The Allied powers led a small-scale invasion of Russia. The intent was primarily to stop Germany from exploiting Russian resources and, to a lesser extent, to support the Whites in the Russian Civil War. Troops landed in Archangel (see North Russia Campaign) and in Vladivostok.

1917–1918

Events of 1917 proved decisive in ending the war, although their effects were not fully felt until 1918. The British naval blockade began to have a serious impact on Germany. In response, in February 1917, the German General Staff convinced Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg to declare unrestricted submarine warfare, with the goal of starving Britain out of the war. Tonnage sunk rose above 500,000 tons per month from February to July. It peaked at 860,000 tons in April. After July, the reintroduced convoy system became extremely effective in neutralizing the U-boat threat. Britain was safe from starvation and German industrial output fell.

The victory of Austria-Hungary and Germany at the Battle of Caporetto led the Allied at the Rapallo Conference to form the Supreme Allied Council to coordinate planning. Previously, British and French armies had operated under separate commands.

In December, the Central Powers signed an armistice with Russia. This released troops for use in the west. Ironically, German troop transfers could have been greater if their territorial acquisitions had not been so dramatic. With German reinforcements and new American troops pouring in, the final outcome was to be decided on the Western front. The Central Powers knew that they could not win a protracted war, but they held high hopes for a quick offensive. Furthermore, the leaders of the Central Powers and the Allies became increasingly fearful of social unrest and revolution in Europe. Thus, both sides urgently sought a decisive victory.[citation needed]

Entry of the United States

The United States originally pursued a policy of isolationism, avoiding conflict while trying to broker a peace. This resulted in increased tensions with Berlin and London. When a German U-boat sank the British liner Lusitania in 1915, with 128 Americans aboard, the U.S. President Woodrow Wilson vowed that "America was too proud to fight" and demanded an end to attacks on passenger ships. Germany complied. Wilson unsuccessfully tried to mediate a settlement. He repeatedly warned that the U.S. would not tolerate unrestricted submarine warfare, in violation of international law and U.S. ideas of human rights. Wilson was under pressure from former president Theodore Roosevelt, who denounced German acts as "piracy."[15] Other factors contributing to the U.S. entry into the war include the suspected German sabotage of both Black Tom in Jersey City, NJ, and the Kingsland Explosion in what is now Lyndhurst, NJ. Wilson's desire to have a seat at negotiations at war's end to advance the League of Nations may also have played a role.[16]

In January 1917, after the Navy pressured the Kaiser, Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare. Britain's secret "Room 40" cryptography group had decrypted the German diplomatic code, and discovered a proposal from Berlin (the famed Zimmermann Telegram) to Mexico to join the war as Germany's ally against the United States, should it join. The proposal suggested that if the U.S. were to enter the war, Mexico should declare war against the United States and enlist Japan as an ally; this would prevent the United States from joining the Allies and deploying troops to Europe, which would give the Germans more time for their unrestricted submarine warfare program to strangle Britain's vital war supplies. In return, the Germans would promise Mexico support in reclaiming Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.[17]

After the British revealed the telegram to the United States, Woodrow Wilson, who claimed neutrality even while calling for the arming of U.S. merchant ships delivering war supplies to combatant Britain, yet supporting the Allied blockading and mining of German ports, released the captured telegram as a way of building support for U.S. entry into the war. After submarines sank seven U.S. merchant ships and the publication of the Zimmerman telegram, Wilson called for war on Germany, which the U.S. Congress declared on 6 April 1917.[18] Crucial to U.S. participation was the massive domestic propaganda campaign executed by the Committee on Public Information overseen by George Creel, which included tens of thousands of respected community leaders giving for all appearances spontaneous but in fact scripted pro-war speeches at millions of public gatherings.

The United States was never formally a member of the Allies but became a self-styled "Associated Power". The United States had a small army, but it drafted four million men and by summer 1918 was sending 10,000 fresh soldiers to France every day. Germany had miscalculated that it would be many more months before they would arrive or that the arrival could be stopped by U-boats.[19]

The United States Navy sent a battleship group to Scapa Flow to join with the British Grand Fleet, destroyers to Queenstown, Ireland and submarines to help guard convoys. Several regiments of U.S. Marines were also dispatched to France. The British and French wanted U.S. units used to reinforce their troops already on the battle lines and not waste scarce shipping on bringing over supplies. The U.S. rejected the first proposition and accepted the second. General John J. Pershing, American Expeditionary Force (AEF) commander, refused to break up U.S. units to be used as reinforcements for British Empire and French units (though he did allow African-American combat units to be used by the French). AEF doctrine called for the use of frontal assaults, which had been discarded by that time by British Empire and French commanders because of the large loss of life sustained throughout the war.[20]

German Spring Offensive of 1918

German General Erich Ludendorff drew up plans (codenamed Operation Michael) for the 1918 offensive on the Western Front. The Spring Offensive sought to divide the British and French forces with a series of feints and advances. The German leadership hoped to strike a decisive blow before significant U.S. forces arrived. Before the offensive began, Ludendorff left the elite Eighth Army in Russia and sending over only a small portion of the German forces to the west.

Operation Michael opened on 21 March 1918. British forces were attacked near Amiens. Ludendorff wanted to split the British and French armies. German forces achieved an unprecedented advance of 60 kilometers (40 miles). For the first time since 1914, the maneuver was successful on the battlefield. [citation needed]

British and French trenches were penetrated using novel infiltration tactics, also named Hutier tactics, after General Oskar von Hutier. Attacks had been characterised by long artillery bombardments and massed assaults. However, in the Spring Offensive, the German Army used artillery only briefly and infiltrated small groups of infantry at weak points. They attacked command and logistics areas and bypassed points of serious resistance. More heavily armed infantry then destroyed these isolated positions. German success relied greatly on the element of surprise.

The front moved to within 120 kilometers (75 mi) of Paris. Three heavy Krupp railway guns fired 183 shells on the capital, causing many Parisians to flee. The initial offensive was so successful that Kaiser Wilhelm II declared 24 March a national holiday. Many Germans thought victory was near. After heavy fighting, however, the offensive was halted. Lacking tanks or motorised artillery, the Germans were unable to consolidate their gains. The sudden stop was also a result of the four AIF (Australian Imperial Forces) divisions that were "rushed" down, thus doing what no other army had done and stopping the German advance in its tracks. While during that time the first Australian division was hurredly sent north again to stop the second German break through.

American divisions, which Pershing had sought to field as an independent force, were assigned to the depleted French and British Empire commands on 28 March. A Supreme War Council of Allied forces was created at the Doullens Conference on 5 November 1917.[21] General Foch was appointed as supreme commander of the allied forces. Haig, Petain and Pershing retained tactical control of their respective armies; Foch would assume a coordinating role, rather than a directing role and the British, French and U.S. commands operated largely independently.[21]

Following Operation Michael, Germany launched Operation Georgette against the northern English channel ports. The Allies halted the drive with limited territorial gains for Germany. The German Army to the south then conducted Operations Blücher and Yorck, broadly towards Paris. Operation Marne was launched on 15 July, attempting to encircle Reims and beginning the Second Battle of the Marne. The resulting Allied counterattack marked their first successful offensive of the war.

By 20 July, the Germans were back at their Kaiserschlacht starting lines, having achieved nothing. Following this last phase of the war in the West, the German Army never again regained the initiative. German casualties between March and April 1918 were 270,000, including many highly trained stormtroopers.

Meanwhile, Germany was falling apart at home. Anti-war marches become frequent and morale in the army fell. Industrial output was 53% of 1913 levels.

New states under war zone

In 1918, the internationally recognized Democratic Republic of Armenia and Democratic Republic of Georgia bordering the Ottoman Empire, and the not-recognized Centrocaspian Dictatorship and South West Caucasian Republic were established.

In 1918, the Dashnaks of Armenian national liberation movement declared the Democratic Republic of Armenia (DRA) through the Armenian Congress of Eastern Armenians (unified form of Armenian National Councils) after the dissolution of Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. Tovmas Nazarbekian become the first Commander-in-chief of DRA. Enver Pasha ordered the creation of a new army to be named the Army of Islam. He ordered the Army of Islam into DRA, with the goal of taking Baku on the Caspian Sea. This new offensive was strongly opposed by the Germans. In early May 1918, the Ottoman army attacked the newly declared DRA. Although the Armenians managed to inflict one defeat on the Ottomans at the Battle of Sardarapat, the Ottoman army won a later battle and scattered the Armenian army. The Republic of Armenia was forced to sign the Treaty of Batum in June 1918.

Allied victory: summer and autumn 1918

The Allied counteroffensive, known as the Hundred Days Offensive, began on 8 August 1918. The Battle of Amiens developed with III Corps Fourth British Army on the left, the First French Army on the right, and the Australian and Canadian Corps spearheading the offensive in the centre. It involved 414 tanks of the Mark IV and Mark V type, and 120,000 men. They advanced 12 kilometers (7 miles) into German-held territory in just seven hours. Erich Ludendorff referred to this day as the "Black Day of the German army". Supply problems caused the offensive to lose momentum. British units had encountered problems when all but seven tanks and trucks ran out of fuel. On 15 August General Haig called a halt and began planning a new offensive in Albert.

The Second Battle of the Somme began on 21 August. The Third and Fourth British Armies and the U.S.II Corps pushed the Second German Army back over a 55 kilometer (34 mile) front. By 2 September, the Germans were back to the Hindenburg Line, their starting point in 1914.

The Allied attack on the Hindenburg Line began on 26 September. 260,000 U.S. soldiers went "over the top". All initial objectives were captured; the U.S. 79th Infantry Division, which met stiff resistance at Montfaucon, took an extra day to capture its objective. The U.S. Army stalled because of supply problems because its inexperienced headquarters had to cope with large units and a difficult landscape.[citation needed] At the same time, French units broke through in Champagne and closed on the Belgian frontier. The most significant advance came from Commonwealth units, as they entered Belgium (liberation of Ghent). The German army had to shorten its front and use the Dutch frontier as an anchor to fight rear-guard actions. This probably saved the army from disintegration but was devastating for morale.[citation needed]

By October, it was evident that Germany could no longer mount a successful defence. They were increasingly outnumbered, with few new recruits. Rations were cut. Ludendorff decided, on 1 October, that Germany had two ways out — total annihilation or an armistice. He recommended the latter at a summit of senior German officials. Allied pressure did not let up.

Meanwhile, news of Germany’s impending military defeat spread throughout the German armed forces. The threat of mutiny was rife. Admiral Reinhard Scheer and Ludendorff decided to launch a last attempt to restore the "valour" of the German Navy. Knowing the government of Max von Baden would veto any such action, Ludendorff decided not to inform him. Nonetheless, word of the impending assault reached sailors at Kiel. Many rebelled and were arrested, refusing to be part of a naval offensive which they believed to be suicidal. Ludendorff took the blame—the Kaiser dismissed him on 26 October. The collapse of the Balkans meant that Germany was about to lose its main supplies of oil and food. The reserves had been used up, but U.S. troops kept arriving at the rate of 10,000 per day.[22]

With power coming into the hands of new men in Berlin, further fighting became impossible.[citation needed] With 6 million German casualties, Germany moved toward peace. Prince Max von Baden took charge of a new government. Negotiations with President Wilson began immediately, in the vain hope that better terms would be offered than with the British and French. Instead Wilson demanded the abdication of the Kaiser. There was no resistance when the social democrat Philipp Scheidemann on 9 November declared Germany to be a republic. Imperial Germany was dead; a new Germany had been born: the Weimar Republic.[23]

End of war

The collapse of the Central Powers came swiftly. Bulgaria was the first to sign an armistice on September 29, 1918 at Saloniki.[24] On October 30, the Ottoman Empire capitulated at Mudros.[25]

On October 24 the Italians began a push which rapidly recovered territory lost after the Battle of Caporetto. This culminated in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, which marked the end of the Austro-Hungarian Army as an effective fighting force. The offensive also triggered the disintegration of Austro-Hungarian Empire. During the last week of October declarations of independence were made in Budapest, Prague and Zagreb. On October 29, the imperial authorities asked Italy for an armistice. But the Italians continued advancing, reaching Trento, Udine and Trieste. On November 3 Austria-Hungary sent a flag of truce to ask for an Armistice. The terms, arranged by telegraph with the Allied Authorities in Paris, were communicated to the Austrian Commander and accepted. The Armistice with Austria was signed in the Villa Giusti, near Padua, on November 3. Austria and Hungary signed separate armistices following the overthrow of the Habsburg monarchy.

Following the outbreak of the German Revolution, a republic was proclaimed on 9 November. The Kaiser fled to the Netherlands. On November 11 an armistice with Germany was signed in a railroad carriage at Compiègne. At 11 a.m. on November 11, 1918 — the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month — a ceasefire came into effect. Opposing armies on the Western Front began to withdraw from their positions. Canadian George Lawrence Price is traditionally regarded as the last soldier killed in the Great War: he was shot by a German sniper and died at 10:58.[26]

A formal state of war between the two sides persisted for another seven months, until signing of the Treaty of Versailles with Germany on June 28, 1919. Later treaties with Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire were signed. However, the latter treaty with the Ottoman Empire was followed by strife (the Turkish Independence War) and a final peace treaty was signed between the Allied Powers and the country that would shortly become the Republic of Turkey, at Lausanne on July 24, 1923.

Some war memorials date the end of the War as being when the Versailles treaty was signed in 1919; by contrast, most commemorations of the War's end concentrate on the armistice of November 11, 1918. Legally the last formal peace treaties were not signed until the Treaty of Lausanne. Under its terms, the Allied forces abandoned Constantinople on the 23rd of August, 1923.

Soldiers' experiences

The soldiers of the war were initially volunteers but increasingly were conscripted into service. Books such as All Quiet on the Western Front detail the mundane time and intense horror of soldiers that fought the war but had no control of the experience they existed in. William Henry Lamin's experience as a front line soldier is detailed in his letters posted in real time (plus 90 years) in a blog [1], as if it were a technology available at the time.

Prisoners of war

About 8 million men surrendered and were held in POW camps during the war. All nations pledged to follow the Hague Convention on fair treatment of prisoners of war. In general, a POW's rate of survival was much higher than their peers at the front.[27] Individual surrenders were uncommon. Large units usually surrendered en masse. At the Battle of Tannenberg 92,000 Russians surrendered. When the besieged garrison of Kaunas surrendered in 1915, 20,000 Russians became prisoners. Over half of Russian losses were prisoners (as a proportion of those captured, wounded or killed); for Austria 32%, for Italy 26%, for France 12%, for Germany 9%; for Britain 7%. Prisoners from the Allied armies totalled about 1.4 million (not including Russia, which lost between 2.5 and 3.5 million men as prisoners.) From the Central Powers about 3.3 million men became prisoners.[28]

Germany held 2.5 million prisoners; Russia held 2.9 million and Britain and France held about 720,000. Most were captured just prior to the Armistice. The U.S. held 48,000. The most dangerous moment was the act of surrender, when helpless soldiers were sometimes gunned down. Once prisoners reached a camp, in general, conditions were satisfactory (and much better than in World War II), thanks in part to the efforts of the International Red Cross and inspections by neutral nations. Conditions were terrible in Russia, starvation was common for prisoners and civilians alike; about 15–20% of the prisoners in Russia died. In Germany food was in short supply, but only 5% died. .[29]

The Ottoman Empire often treated POWs poorly. Some 11,800 British Empire soldiers, most of them Indians, became prisoners after the Siege of Kut, in Mesopotamia, in April 1916; 4,250 died in captivity. [30] Although many were in very bad condition when captured, Ottoman officers forced them to march 1,100 kilometres (684 mi) to Anatolia. A survivor said: "we were driven along like beasts, to drop out was to die."[31] The survivors were then forced to build a railway through the Taurus Mountains.

The most curious case occurred in Russia, where the prisoners from the Czech Legion of the Austro-Hungarian army, were released in 1917. They re-armed themselves and briefly became a military and diplomatic force during the Russian Civil War.

War crimes

Armenian Genocide

The ethnic cleansing of Armenians during the final years of the Ottoman Empire is widely considered genocide. The Turks accused the (Christian) Armenians of preparing to ally themselves with Russia and saw the entire Armenian population as an enemy. The exact number of deaths is unknown. Most estimates are between 800,000 and 1.5 million.[32] Turkish governments have consistently rejected charges of genocide, often arguing that those who died were simply caught up in the fighting or that killings of Armenians were justified by their individual or collective treason. These claims have often been labeled as historical revisionism by western scholars.

Rape of Belgium

In Belgium, German troops, in fear of French and Belgian guerrilla fighters, or francs-tireurs, massacred townspeople in Andenne (211 dead), Tamines (384 dead), and Dinant (612 dead). The victims included women and children. On 25 August 1914, the Germans set fire to the town of Leuven, burned the library containing about 230,000 books, killed 209 civilians and forced 42,000 to evacuate. These actions brought worldwide condemnation.[33]

Economics and manpower issues

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased for three Allies (Britain, Italy, and U.S.), but decreased in France and Russia, in neutral Netherlands and in the main three Central Powers. The shrinkage in GDP in Austria, Russia, France, and the Ottoman Empire reached 30 to 40%. In Austria, for example, most of the pigs were slaughtered and, at war's end, there was no meat.

All nations had increases in the government’s share of GDP, surpassing fifty percent in both Germany and France and nearly reaching fifty percent in Britain. To pay for purchases in the United States, Britain cashed in its massive investments in American railroads and then began borrowing heavily on Wall Street. President Wilson was on the verge of cutting off the loans in late 1916, but allowed a massive increase in U.S. government lending to the Allies. After 1919, the U.S. demanded repayment of these loans, which, in part, were funded by German reparations, which, in turn, were supported by American loans to Germany. This circular system collapsed in 1931 and the loans were never repaid.

One of the most dramatic effects was the expansion of governmental powers and responsibilities in Britain, France, the United States, and the Dominions of the British Empire. In order to harness all the power of their societies, new government ministries and powers were created. New taxes were levied and laws enacted, all designed to bolster the war effort; many of which have lasted to this day.

At the same time, the war strained the abilities of the formerly large and bureaucratised governments such as in Austria-Hungary and Germany. Here, however, the long-term effects were clouded by the defeat of these governments.

Families were altered by the departure of many men. With the death or absence of the primary wage earner, women were forced into the workforce in unprecedented numbers. At the same time, industry needed to replace the lost laborers sent to war. This aided the struggle for voting rights for women.

As the war slowly turned into a war of attrition, conscription was implemented in some countries. This issue was particularly explosive in Canada and Australia. In the former it opened a political gap between French-Canadians — who claimed their true loyalty was to Canada and not the British Empire — and the Anglophone majority who saw the war as a duty to both Britain and Canada. Prime Minister Robert Borden pushed through a Military Service Act, provoking the Conscription Crisis of 1917. In Australia, a sustained pro-conscription campaign by Prime Minister Billy Hughes, caused a split in the Australian Labor Party and Hughes formed the Nationalist Party of Australia in 1917 to pursue the matter. Nevertheless, the labour movement, the Catholic Church, and Irish nationalist expatriates successfully opposed Hughes' push, which was rejected in two plebiscites.

In Britain, rationing was finally imposed in early 1918, limited to meat, sugar, and fats (butter and oleo), but not bread. The new system worked smoothly. From 1914 to 1918 trade union membership doubled, from a little over four million to a little over eight million. Work stoppages and strikes became frequent in 1917–18 as the unions expressed grievances regarding prices, alcohol control, pay disputes, fatigue from overtime and working on Sundays and inadequate housing. Conscription put into uniform nearly every physically fit man, six of ten million eligible. Of these, about 750,000 lost their lives and 1,700,000 were wounded. Most deaths were to young unmarried men; however, 160,000 wives lost husbands and 300,000 children lost fathers.[34]

Britain turned to her colonies for help in obtaining essential war materials whose supply had become difficult from traditional sources. Geologists, such as Albert Ernest Kitson, were called upon to find new resources of precious minerals in the African colonies. Kitson discovered important new deposits of manganese, used in munitions production, in the Gold Coast.[35]

Technology

The First World War began as a clash of 20th century technology and 19th century tactics, with inevitably large casualties. By the end of 1917, however, the major armies, now numbering millions of men, had modernised and were making use of telephone, wireless communication, armoured cars, tanks and aircraft. Infantry formations were reorganised, so that 100-man companies were no longer the main unit of maneuver. Instead, squads of 10 or so men, under the command of a junior NCO, were favoured. Artillery also under went a revolution.

In 1914, cannons were positioned in the front line and fired directly at their targets. By 1917, indirect fire with guns (as well as mortars and even machine guns) was commonplace, using new techniques for spotting and ranging, notably aircraft and (often overlooked) field telephone. Counter-battery missions became commonplace, also, and sound detection was used to locate enemy batteries.

Germany was far ahead of the Allies in utilizing heavy indirect fire. She employed 150 and 210 mm howitzers in 1914 when the typical French and British guns were only 75 and 105 mm. The British had a 6 inch (152 mm) howitzer, but it was so heavy it had to be assembled for firing. Germans also fielded Austrian 305 mm and 420 mm guns, and already by the beginning of the war had inventories of various calibers of Minenwerfer ideally suited for trench warfare.[36]

Much of the combat involved trench warfare, where hundreds often died for each yard gained. Many of the deadliest battles in history occurred during the First World War. Such battles include Ypres, the Marne, Cambrai, the Somme, Verdun, and Gallipoli. The Haber process of nitrogen fixation was employed to provide the German forces with a constant supply of gunpowder, in the face of British naval blockade. Artillery was responsible for the largest number of casualties and consumed vast quantities of explosives. The large number of head-wounds caused by exploding shells and fragmentation forced the combatant nations to develop the modern steel helmet, led by the French, who introduced the Adrian helmet in 1915. It was quickly followed by the Brodie helmet, worn by British Imperial and U.S. troops, and in 1916 by the distinctive German Stahlhelm, a design, with improvements, still in use today.

There was chemical warfare and small-scale strategic bombing, both[citation needed] of which were outlawed by the 1907 Hague Conventions. Both were of limited tactical effectiveness.[citation needed]

The widespread use of chemical warfare was a distinguishing feature of the conflict. Gases used included chlorine, mustard gas and phosgene. Only a small proportion of total war casualties were caused by gas. Effective countermeasures to gas attacks were quickly created, such as gas masks.

The most powerful land-based weapons were railway guns weighing hundreds of tons apiece. These were nicknamed Big Berthas, even though the namesake was not a railway gun. Germany developed the Paris Gun, able to bombard Paris from over 100 km (60mi), though shells were relatively light at 94 kilograms (210 lb). While the Allies had railway guns, German models severely out-ranged and out-classed them.

Fixed-wing aircraft were first used militarily by the Italians in Libya 23 October 1911 during the Italo-Turkish War for reconaissance, soon followed by the dropping of grenades and aerial photography the next year. By 1914 the military utility was obvious. They were initially used for reconnaissance and ground attack. To shoot down enemy planes, anti-aircraft guns and fighter aircraft were developed. Strategic bombers were created, principally by the Germans and British, though the former used Zeppelins as well.

Towards the end of the conflict, aircraft carriers were used for the first time, with HMS Furious launching Sopwith Camels in a raid against the Zepplin hangars at Tondern in 1918.

German U-boats (submarines) were deployed after the war began. Alternating between restricted and unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic, they were employed by the Kaiserliche Marine in a strategy to deprive the British Isles of vital supplies. The deaths of British merchant sailors and the seeming invulnerability of U-boats led to the development of depth charges (1916), hydrophones (passive sonar, 1917), blimps, hunter-killer submarines (HMS R 1, 1917), ahead-throwing weapons, and dipping hydrophones (the latter two both abandoned in 1918). To extend their operations, the Germans proposed supply submarines (1916). Most of these would be forgotten in the interwar period until World War II revived the need.

Trenches, machineguns, air reconnaissance, barbed wire, and modern artillery with fragmentation shells helped bring the battle lines of World War I to a stalemate. The British sought a solution with the creation of the tank and mechanised warfare. The first tanks were used during the Battle of the Somme on 15 September 1916. Mechanical reliability became an issue, but the experiment proved its worth. Within a year, the British were fielding tanks by the hundreds and showed their potential during the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917, by breaking the Hindenburg Line, while combined arms teams captured 8000 enemy soldiers and 100 guns. Light automatic weapons also were introduced, such as the Lewis Gun and Browning automatic rifle.

Manned observation balloons, floating high above the trenches, were used as stationary reconnaissance platforms, reporting enemy movements and directing artillery. Balloons commonly had a crew of two, equipped with parachutes.[37] In the event of an enemy air attack, the crew could parachute to safety. At the time, parachutes were too heavy to be used by pilots of aircraft (with their marginal power output) and smaller versions would not be developed until the end of the war; they were also opposed by British leadership, who feared they might promote cowardice.[38] Recognised for their value as observation platforms, balloons were important targets of enemy aircraft. To defend against air attack, they were heavily protected by antiaircraft guns and patrolled by friendly aircraft. Blimps and balloons contributed to air-to-air combat among aircraft, because of their reconnaissance value, and to the trench stalemate, because it was impossible to move large numbers of troops undetected. The Germans conducted air raids on England during 1915 and 1916 with airships, hoping to damage British morale and cause aircraft to be diverted from the front lines. The resulting panic took several squadrons of fighters from France.[39]

Another new weapon, flamethrowers, were first used by the German army and later adopted by other forces. Although not of high tactical value, they were a powerful, demoralizing weapon and caused terror on the battlefield. It was a dangerous weapon to wield, as its heavy weight made operators vulnerable targets.

Opposition to the war

The trade union and socialist movements had long voiced their opposition to a war, which they argued, meant only that workers would kill other workers in the interest of capitalism. Once war was declared, however, the vast majority of socialists and trade unions backed their governments. The exceptions were the Bolsheviks and the Italian Socialist Party, and individuals such as Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg and their followers in Germany. There were also small anti-war groups in Britain and France. Other opposition came from conscientious objectors - some socialist, some religious - who refused to fight. In Britain 16,000 [citation needed] people asked for conscientious objector status. Many suffered years of prison, including solitary confinement and bread and water diets. Even after the war, in Britain many job advertisements were marked "No conscientious objectors need apply". Many countries jailed those who spoke out against the conflict. These included Eugene Debs in the United States and Bertrand Russell in Britain. In the U.S. the 1917 Espionage Act effectively made free speech illegal and many served long prison sentences for statements of fact deemed unpatriotic. The Sedition Act of 1918 made any statements deemed "disloyal" a federal crime. Publications at all critical of the government's war policies were removed from circulation by postal censors. [40]

Aftermath

No other war had changed the map of Europe so dramatically — four empires disappeared: the German, Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman and the Russian. Four defunct dynasties, the Hohenzollerns, the Habsburg, Romanovs and the Ottomans together with all their ancillary aristocracies, all fell after the war. Belgium was badly damaged, as was France with 1.4 million soldiers dead, not counting other casualties. Germany and Russia were similarly affected. The war had profound economic consequences. In addition, a major influenza epidemic that started in Western Europe in the latter months of the war, killed millions in Europe and then spread around the world. Overall, the Spanish flu killed at least 50 million people.[41][42]

Peace treaties

After the war, the Allies imposed a series of peace treaties on the Central Powers. The 1919 Versailles Treaty, which Germany was kept under blockade until she signed, ended the war. It declared Germany responsible for the war and required Germany to pay enormous war reparations and awarding territory to the victors. Unable to pay them with exports (a result of territorial losses and postwar recession),[43] she did so by borrowing from the United States, until the reparations were suspended in 1931. The "Guilt Thesis" became a controversial explanation of events in Britain and the United States. The Treaty of Versailles caused enormous bitterness in Germany, which nationalist movements, especially the Nazis, exploited. (See Dolchstosslegende). The treaty contributed to one of the worst economic collapses in German history, sparking runaway inflation in the 1920s.

The Ottoman Empire was to be partitioned by the Treaty of Sèvres in 1920. The treaty, however, was never ratified by the Sultan and was rejected by the Turkish republican movement. This led to the Turkish Independence War and, ultimately, to the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne.

Austria-Hungary was also partitioned, largely along ethnic lines. The details were contained in the Treaty of Saint-Germain and the Treaty of Trianon.

New national identities

Poland reemerged as an independent country, after more than a century. Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia were entirely new nations. Russia became the Soviet Union and lost Finland, Estonia, Lithuania and Latvia, which became independent countries. The Ottoman Empire was soon replaced by Turkey and several other countries in the Middle East.

Some people think that the Allies opened the way to more colonization with their policy, because with it the Allies could colonise territories owned by the Ottoman Empire and Austro-Hungarian Empire, by making them independent.

Postwar colonization in the Ottoman Empire led to many future problems still unresolved today. Conflict between mostly Jewish colonists and the existing, mostly Muslim, population intensified, probably exacerbated by the Holocaust, which stimulated Jewish migration and encouraged the new immigrants to fight for survival, a homeland, or both. However, any new homeland for immigrants would cause hardships for the existing population, especially if the former displaced the latter. The United Nations partitioned Palestine in 1947 with Jewish but not Arab and Muslim approval. After the creation of the state of Israel, a series of wars broke out between Israel and its neighbors, Egypt, Jordan, and Syria, in addition to unrest from the Palestinian population and terrorist activity by Palestinians and others reaching to Iran and beyond. Lasting peace in the region remains an elusive goal almost a century later.

In the British Empire, the war unleashed new forms of nationalism. In Australia and New Zealand the Battle of Gallipoli became known as those nations' "Baptism of Fire". It was the first major war in which the newly established countries fought and it was one of the first times that Australian troops fought as Australians, not just subjects of the British Crown. Anzac Day, commemorating the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps, celebrates this defining moment.

This effect was even greater in Canada. Canadians proved they were a nation and not merely subjects of a distant empire. Indeed, following Vimy, many Canadians began to refer to Canada as a nation "forged from fire". Canadians had proved themselves on the same battlefield where the British and French had previously faltered, and were respected internationally for their accomplishments. Canada entered the war as a Dominion of the British Empire, but when the war came to a close, Canada emerged as a fully independent nation. Canadian diplomats played a significant role in negotiating the Versailles Treaty. Canada was an independent signatory of the treaty, whereas other Dominions were represented by Britain. Canadians commemorate the war dead on Remembrance Day. In French Canada, however, the Conscription Crisis left bitterness in its wake.

Social trauma

The experiences of the war led to a collective trauma for all participating countries. The optimism of the 1900s was gone and those who fought in the war became known as the Lost Generation. For the next few years, much of Europe mourned. Memorials were erected in thousands of villages and towns. The soldiers returning home from World War I suffered greatly from the horrors they had witnessed. Called shell shock at the time, many returning veterans suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder.

The social trauma caused by years of fighting manifested itself in different ways. Some people were revolted by nationalism and its results. They began to work toward a more internationalist world, supporting organisations such as the League of Nations. Pacifism became increasingly popular. Others had the opposite reaction, feeling that only strength and military-might could be relied upon in a chaotic and inhumane world. Anti-modernist views were an outgrowth of the many changes taking place in society. The rise of Nazism and fascism included a revival of the nationalist spirit and a rejection of many post-war changes. Similarly, the popularity of the Dolchstosslegende ("backstab") was a testament to the psychological state of defeated Germany and was a rejection of responsibility for the conflict. The myth of betrayal became common and the aggressors came to see themselves as victims. The popularity of the 'Dolchstosslegende myth played a significant role in the outbreak of World War II and the Holocaust. A sense of disillusionment and cynicism became pronounced, with nihilism growing in popularity. This disillusionment for humanity found a cultural climax with the Dadaist artistic movement. Many believed the war heralded the end of the world as they had known it, including the collapse of capitalism and imperialism. Communist and socialist movements around the world drew strength from this theory and enjoyed a level of popularity they had never known before. These feelings were most pronounced in areas directly or harshly affected by the war.

In May 1915, during the Second Battle of Ypres, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, M.D., of Guelph, Ontario, Canada wrote the memorable poem In Flanders Fields as a salute to those who perished in the Great War. Published in Punch on December 8, 1918, it is still recited today, especially on Remembrance Day and Memorial Day.[44][45]

Other names

Before World War II, the war was also known as The Great War, The World War, The War to End All Wars, The Kaiser's War, The War of the Nations and The War in Europe. In France and Belgium it was sometimes referred to as La Guerre du Droit (the War for Justice) or La Guerre Pour la Civilisation / de Oorlog tot de Beschaving (the War to Preserve Civilization), especially on medals and commemorative monuments. The term used by official histories of the war in Britain and Canada is The First World War, while American histories generally use the term World War I.

German biologist and philosopher Ernst Haeckel wrote this shortly after the start of the war:

There is no doubt that the course and character of the feared "European War"...will become the first world war the full sense of the word. Indianapolis Star September 20, 1914[46]

This is the first known instance of the term First World War, which previously had been dated to 1931 for the earliest usage. The term was used again near the end of the war. English journalist Charles à Repington (1858–1925) wrote: