Machu Picchu

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

View of Huayna Picchu towering above the ruins of Machu Picchu

View of Huayna Picchu towering above the ruins of Machu Picchu | |

| Criteria | Mixed: i, iii, vii, ix |

| Reference | 274 |

| Inscription | 1983 (7th Session) |

Machu Picchu (Template:Lang-qu, "Old Peak") is a pre-Columbian Inca site located at 2,430 meters (7,970 ft) above sea level[1] on a mountain ridge above the Urubamba Valley in Peru, about 70 km (44 mi) northwest of Cusco. Often referred to as "The Lost City of the Incas", Machu Picchu is probably the most familiar symbol of the Inca Empire. It was built around the year 1450 and abandoned a hundred years later, at the time of the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire. Forgotten for centuries by all except for a few locals, the site was brought to worldwide attention in 1911 by Hiram Bingham, an American historian. Since then, Machu Picchu has become an important tourist attraction, it was declared a Peruvian Historical Sanctuary in 1981 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1983.

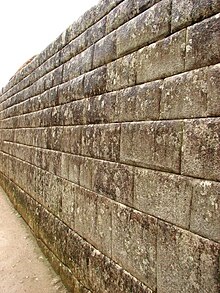

Machu Picchu was built in a classic Inca architectural style of polished dry-stone walls. Its primary buildings are the Intihuatana, the Temple of the Sun and the Room of the Three Windows located in what is known by archaeologist as the Sacred District of Machu Picchu. There are concerns about the impact of tourism to the site as its visitors reached 400,000 in 2003. On September 2007, Peru and Yale University reached an agreement regarding return of artifacts removed from Macchu Picchu in the early 20th century by Hiram Bingham.

History

Machu Picchu was constructed around 1450, at the height of the Inca Empire, and was abandoned less than 100 years later, as the empire collapsed under Spanish conquest. One theory maintains that Machu Picchu was an Incan "llacta": a settlement built up to control the economy of the conquered regions and that it may have been built with the purpose of protecting the most select of the Incan aristocracy in the event of an attack. Based on research conducted by scholars such as John Rowe and Richard Burger, most archaeologists now believe that, rather than a defensive retreat, Machu Picchu was an estate of the Inca emperor Pachacuti. Johan Reinhard presents evidence that the site was selected based on its position relative to sacred landscape features, especially mountains that are in alignment with key astronomical events.

Although the citadel is located only about 50 miles from Cusco, the Inca capital, it was never found and destroyed by the Spanish, as were many other Inca sites. Over the centuries, the surrounding jungle grew to enshroud the site, and few knew of its existence. On July 24 1911, Machu Picchu was brought to the attention of the West by Hiram Bingham, an American historian then employed as a lecturer at Yale University. He was led there by locals who frequented the site. Bingham undertook archaeological studies and completed a survey of the area. Bingham coined the name "The Lost City of the Incas", which was the title of his first book. He never gave any credit to those who led him to Machu Picchu, mentioning only "local rumor" as his guide.

Bingham had been searching for the city of Vitcos, the last Inca refuge and spot of resistance during the Spanish conquest of Peru. In 1911, after various years of previous trips and explorations around the zone, he was led to the citadel by Quechuans who were living in Machu Picchu in the original Inca infrastructure. Bingham made several more trips and conducted excavations on the site through 1915. He wrote a number of books and articles about the discovery of Machu Picchu.

Simone Waisbard, a long-time researcher of Cusco, claims Enrique Palma, Gabino Sánchez and Agustín Lizárraga left their names engraved on one of the rocks there on July 14 1901, having rediscovered it before Bingham. Likewise, in 1904 an engineer named Franklin supposedly spotted the ruins from a distant mountain. He told Thomas Paine, an English Plymouth Brethren Christian missionary living in the region, about the site, Paine's family members claim. In 1906, Paine and another Brethren missionary named Stuart E McNairn (1867–1956) supposedly climbed up to the ruins.

Bingham and others hypothesized that the citadel was the traditional birthplace of the Inca people or the spiritual center of the "virgins of the suns", while curators of a recent exhibit have speculated that Machu Picchu was a royal retreat.

It is thought that the site was chosen for its unique location and geological features. It is said that the silhouette of the mountain range behind Machu Picchu represents the face of the Inca looking upward towards the sky, with the largest peak, Huayna Picchu (meaning Young Peak), representing his pierced nose.[citation needed]

In 1913, the site received significant publicity after the National Geographic Society devoted their entire April issue to Machu Picchu. In 1981 an area of 325.92 square kilometers surrounding Machu Picchu was declared a "Historical Sanctuary" of Peru. This area, which is not limited to the ruins themselves, also includes the regional landscape with its flora and fauna, highlighting the abundance of orchids.

Machu Picchu was designated as a World Heritage Site in 1983 when it was described as "an absolute masterpiece of architecture and a unique testimony to the Inca civilization".[2] On July 7, 2007, Machu Picchu was voted as one of New Open World Corporation's New Seven Wonders of the World.

Location

Machu Picchu is 70 kilometers northwest of Cusco, on the crest of the mountain Machu Picchu, located about 2,350 meters above sea level. It is one of the most important archaeological centers in South America and the most visited tourist attraction in Peru.

From the top, at the cliff of Machu Picchu, there is a vertical precipice of 600 meters ending at the foot of the Urubamba River. The location of the city was a military secret because its deep precipices and mountains were an excellent natural defense. The Inca Bridge, an Inca rope bridge across the Urubamba River in the Pongo de Mainique, provided a secret entrance for the Inca army.

Architecture

All of the construction in Machu Picchu uses the classic Inca architectural style of polished dry-stone walls of regular shape. The Incas were masters of this technique, called ashlar, in which blocks of stone are cut to fit together tightly without mortar. Many junctions in the central city are so perfect that not even a knife fits between the stones.

The Incas never used the wheel in any practical manner. How they moved and placed enormous blocks of stones is a mystery, although the general belief is that they used hundreds of men to push the stones up inclined planes.

The space is composed of 140 constructions including temples, sanctuaries, parks and residences (houses with thatched roofs). There are more than one hundred flights of stone steps – often completely carved from a single block of granite – and a great number of water fountains, interconnected by channels and water-drainages perforated in the rock, designed for the original irrigation system. Evidence has been found to suggest that the irrigation system was used to carry water from a holy spring to each of the houses in turn.

According to archaeologists, the urban sector of Machu Picchu was divided into three great districts: the Sacred District, the Popular District, to the south, and the District of the Priests and the Nobility.

Located in the first zone are the primary archaeological treasures: the Intihuatana, the Temple of the Sun and the Room of the Three Windows. These were dedicated to Inti, their sun god and greatest deity. The Popular District, or Residential District, is the place where the lower class people lived. It includes storage buildings and simple houses to live in.

In the royalty area, a sector existed for the nobility: a group of houses located in rows over a slope; the residence of the Amautas (wise persons) was characterized by its reddish walls, and the zone of the Ñustas (princesses) had trapezoid-shaped rooms. The Monumental Mausoleum is a carved statue with a vaulted interior and carved drawings. It was used for rites or sacrifices.

As part of their road system, the Inca built a road to Machu Picchu. Today, tens of thousands of tourists walk the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu, acclimatising at Cusco before starting on a two- to four-day journey on foot from the Urubamba valley up through the Andes mountain range.

Concerns over tourism

Machu Picchu is a UNESCO World Heritage site. As Peru’s most visited tourist attraction and major revenue generator, it is continually threatened by economic and commercial forces. In the late 1990s, the Peruvian government granted concessions to allow the construction of a cable car to the ruins and development of a luxury hotel, including a tourist complex with boutiques and restaurants. These plans were met with protests from scientists, academics and the Peruvian public, worried that the greater numbers of visitors would pose tremendous physical burdens on the ruins.

A growing number of people visit Machu Picchu (400,000 in 2003[3]). For this reason, there were protests against a plan to build a further bridge to the site[4] and a no-fly zone exists in the area.[5] UNESCO is considering putting Machu Picchu on its list of endangered World Heritage Sites.[4]

Damage to the site due to usage has occurred. In September 2000 a centuries-old sundial called Intihuatana, or "hitching post for the sun," was damaged when a 1,000-pound crane fell onto it. The crane was being used by a crew hired by J. Walter Thompson advertising agency to film an advertisement for Cusqueña beer. "Machu Picchu is the heart of our archaeological heritage and the Intihuatana is the heart of Machu Picchu. They've struck at our most sacred inheritance," said Federico Kaufmann Doig, a Peruvian archaeologist."[1]

Controversy with Yale University

During his early years in Peru, Bingham built strong relationships with top Peruvian officials. As a result, he had little trouble obtaining necessary permission, paperwork, and permits to travel throughout the country and borrow archeological artifacts. Upon returning to Yale University, Bingham had collected around 5,000 such objects to be kept in Yale's care until such time as the Peruvian government requested their return. Recently, the Peruvian government requested the return of all cultural material, and at the refusal of Yale University to do so, began to consider legal action.[6]

On March 14, 2006, the Hartford Courant reported that the wife of Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo had accused Yale University of profiting from Peru's cultural heritage by claiming title to more than 250 museum-quality pieces that had been removed from Macchu Picchu by Hiram Bingham in 1912 and had been on display at Yale's Peabody Museum ever since. Some of the material Bingham removed was returned to Peru but Yale has kept the rest saying its position was supported by federal case law involving Peruvian antiquities.[7]

On August 14, 2007, the Hartford Courant reported that Yale had agreed to turn over to Peru an inventory of some 300 museum-quality pieces in its collection. The breakthrough in negotiations between Yale and the Peruvian government may help decide who gets to keep the artifacts. Peru's new President Alan Garcia has appointed a delegation to continue talks with Yale and appears willing to settle the dispute without pursuing the lawsuit threatened by his predecessor, Alejandro Toledo.[8]

On September 19, 2007, the Hartford Courant reported that Peru and Yale University had reached an agreement regarding return of artifacts removed from Macchu Picchu in the early 20th century by Hiram Bingham. The agreement includes sponsorship of a joint traveling exhibition and construction of a new museum and research center in Cusco that Yale will advise Peru on. Yale acknowledges Peru's title to all the excavated objects from Machu Picchu but Yale will share rights with Peru in the research collection, part of which will remain at Yale as an object of continuing study.[9]

Panoramic views

See also

Notes

- ^ "Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu — UNESCO World Heritage Centre". UNESCO. 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessdaymonth=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "UNESCO advisory body evaluation" (PDF).

- ^ "Row erupts over Peru's tourist treasure", BBC News Online. 27 December 2003

- ^ a b "Bridge stirs the waters in Machu Picchu", BBC News Online, 1 February 1 2007

- ^ "Peru bans flights over Inca ruins", BBC News Online, 8 September 2006

- ^ Andrew Mangino (2006-04-12). "Elections could avert Peru's lawsuit". Yale Daily News Publishing Company, Inc.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Hartford Courant. "Peru Presses Yale On Relics." March 14, 2006".

- ^ "Hartford Courant. "Yale Will Give Peru A List Of Artifacts." August 14, 2007".

- ^ Hartford Courant. "Yale To Return Incan Artifacts" by Edmund H. Mahoney. September 19, 2007

References

- Bingham, Hiram (1979 [1930]) Machu Picchu a Citadel of the Incas. Hacker Art Books, New York.

- Burger, Richard and Lucy Salazar (eds.) (2004) Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas. Yale University Press, New Haven.

- Frost, Peter (1995) Machu Picchu Historical Sanctuary. Nueves Imágines, Lima.

- Reinhard, Johan (2002) Machu Picchu: The Sacred Center. Lima: Instituto Machu Picchu (2nd ed.).

- Richardson, Don (1981) Eternity in their Hearts. Regal Books, Ventura. ISBN 0-8307-0925-8, pp. 34–35.

- Wright, Kenneth and Alfredo Valencia (2000) Machu Picchu: A Civil Engineering Marvel. ASCE Press, Reston.

External links

- Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu (World Heritage)

- Information about Machu Picchu and the Incas

- Virtual Tour to Machu Picchu

- Machu Picchu on National Geographic

- Machu Picchu on Mappington Maps, Photos, Videos, Articles, and User Opinions of Machu Picchu

- Template:Wikitravel

- A pictorial guide to Machu Picchu