England

England | |

|---|---|

| Motto: [Dieu et mon droit] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (French) "God and my right" | |

| Anthem: No official anthem specific to England — the anthem of the United Kingdom is "God Save the Queen". See also Proposed English National Anthems. | |

Location of England (orange) – in Europe (tan & white) | |

| Capital and largest city | London |

| Official languages | English1 |

| Ethnic groups | 84.70% White British 5.30% South Asian 3.20% White Other 2.69% Black 1.57% Mixed Race 1.20% White Irish 0.70% Chinese 0.60% Other |

| Demonym(s) | English |

| Government | Constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Queen Elizabeth II |

• Prime Minister (of the United Kingdom) | Gordon Brown MP |

| Unified | |

• by Athelstan | AD 927 |

| Area | |

• Total | 130,395 km2 (50,346 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2006 estimate | 50,762,900² |

• 2001 census | 49,138,831 |

• Density | 388.7/km2 (1,006.7/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2006 estimate |

• Total | $1.9 trillion (6th) |

• Per capita | US$38,000 (6th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2006 estimate |

• Total | $2.2 trillion (5th) |

• Per capita | $53,000 (10th) |

| HDI (2006) | Error: Invalid HDI value |

| Currency | Pound sterling (GBP) |

| Time zone | UTC0 (GMT) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| Calling code | 44 |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-ENG |

| Internet TLD | .uk³ |

| |

England (Template:PronEng) (Template:Lang-ang, Middle English: Engelond) is the largest and most populous constituent country[1][2] of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Its inhabitants account for more than 83% of the total population of the United Kingdom,[3] while the mainland territory of England occupies most of the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west. Elsewhere, it is bordered by the North Sea, Irish Sea, Celtic Sea, Bristol Channel and English Channel.

England became a unified state in the year 927 and takes its name from the Angles, one of the Germanic tribes who settled there during the 5th and 6th centuries. The capital of England is London, the largest urban area in Great Britain, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most, but not all, measures.[4]

England ranks amongst the world's most influential and far-reaching centres of cultural development.[5] It is the place of origin of the English language and the Church of England, and English law forms the basis of the legal systems of many countries; in addition, London was the centre of the British Empire, and the country was the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution.[6] England was the first country in the world to become industrialised. [citation needed] England is home to the Royal Society, which laid the foundations of modern experimental science. England was the world's first modern parliamentary democracy[7] and consequently many constitutional, governmental and legal innovations that had their origin in England have been widely adopted by other nations.

The Kingdom of England was a separate state until 1 May 1707, when the Acts of Union resulted in a political union with the Kingdom of Scotland to create the Kingdom of Great Britain,[8] with the Principality of Wales already in the English state.

Etymology and usage

England is named after the Angles, the largest of the Germanic tribes who settled in England in the 5th and 6th centuries, and who are believed to have originated in the peninsula of Angeln, in what is now Denmark and northern Germany.[9] (The further etymology of this tribe's name remains uncertain, although a popular theory holds that it need be sought no further than the word angle itself, and refers to a fish-hook-shaped region of Holstein.[10]

The Angles' name has had various spellings. The earliest known reference to these people is under the Latinised version Anglii used by Tacitus in chapter 40 of his Germania,[11] written around 98 AD. He gives no precise indication of their geographical position within Germania, but states that, with six other tribes, they worshipped a goddess named Nerthus, whose sanctuary was situated on "an island in the Ocean".

The early 8th century historian Bede, in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People), refers to the English people as Angelfolc (in English) or Angli (in Latin).[12]

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first known usage of "England" referring to the southern part of the island of Great Britain was in 897, with the modern spelling first used in 1538.[13]

The word "England" is often used colloquially—and incorrectly—to refer to Great Britain or the United Kingdom as a whole.[14] There are many instances of this usage in history, where references to England are actually intended to include Scotland and Wales as well.[15] The term is used throughout the world and even by English people; the usage is problematic and causes offence in many parts of Britain.

Researcher Thomas Mally found that the word "England" often relates to the Latin translation for "the prosperous."

History

Prehistory

Bones and flint tools found in Norfolk and Suffolk show that Homo erectus lived in what is now England about 700,000 years ago.[16] At this time, England was joined to mainland Europe by a large land bridge. The current position of the English Channel was a large river flowing westwards and fed by tributaries that would later become the Thames and the Seine. This area was greatly depopulated during the period of the last major ice age, as were other regions of the British Isles. In the subsequent recolonisation, after the thawing of the ice, genetic research shows that present-day England was the last area of the British Isles to be repopulated,[17] about 13,000 years ago. The migrants arriving during this period contrast with the other of the inhabitants of the British Isles, coming across lands from the south east of Europe, whereas earlier arriving inhabitants came north along a coastal route from Iberia. These migrants would later adopt the Celtic culture that came to dominate much of western Europe.

Roman conquest of Britain

By AD 43, the time of the main Roman invasion, Britain had already been the target of frequent invasions, planned and actual, by forces of the Roman Republic and Roman Empire. It was first invaded by the Roman dictator Julius Caesar in 55 BC, but it was conquered more fully by the Emperor Claudius in 43 AD. Like other regions on the edge of the empire, Britain had long enjoyed trading links with the Romans, and their economic and cultural influence was a significant part of the British late pre-Roman Iron Age, especially in the south. With the fall of the Roman Empire 400 years later, the Romans left England.

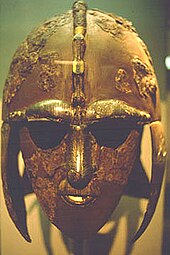

Anglo-Saxons

The History of Anglo-Saxon England covers the history of early mediaeval England from the end of Roman Britain and the establishment of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the 5th century until the Conquest by the Normans in 1066.[18]

Fragmentary knowledge of Anglo-Saxon England in the 5th and 6th centuries comes from the British writer Gildas (6th century) the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (a history of the English people begun in the 9th century), saints' lives, poetry, archaeological findings, and place-name studies.

The dominant themes of the seventh to tenth centuries were the spread of Christianity and the political unification of England. Christianity is thought to have come from three directions—from Rome to the south, and Scotland and Ireland to the north and west.

From about 500, England was divided (it is believed) into seven petty kingdoms, known as the Heptarchy: Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex, and Wessex.

The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms tended to coalesce by means of warfare. As early as the time of Ethelbert of Kent, one king could be recognised as Bretwalda ("Lord of Britain"). Generally speaking, the title fell in the 7th century to the kings of Northumbria, in the 8th to those of Mercia, and in the 9th, to Egbert of Wessex, who in 825 defeated the Mercians at the Battle of Ellendun. In the next century his family came to rule all England.

Kingdom

Originally, England (or Englaland) was a geographical term to describe the part of Britain occupied by the Anglo-Saxons, rather than a name of an individual nation-state. It became politically united through the expansion of the kingdom of Wessex, whose king Athelstan brought the whole of England under one ruler for the first time in 927, although unification did not become permanent until 954, when Edred defeated Eric Bloodaxe and became King of England.

In 1016 England was conquered by the Danish king Canute the Great, and became the centre of government for his short-lived empire which included Denmark and Norway. In 1042 England became a separate kingdom again with the accession of Edward the Confessor, heir of the native English dynasty.

The Kingdom of England (including Wales) continued to exist as an independent nation-state right through to the Acts of Union. However the political ties and direction of England were changed forever by the Norman Conquest in 1066.

Middle Ages

The next few hundred years saw England as a major part of expanding and dwindling empires based in France, with the "Kings of England" using England as a source of troops to enlarge their personal holdings in France for many years (Hundred Years' War) ; in fact the English crown did not relinquish its last foothold on mainland France until Calais was lost during the reign of Mary Tudor (the Channel Islands are still crown dependencies, though not part of the UK).

In the 13th Century, through conquest Wales (the remaining Romano-Celts) was brought under the control of English monarchs. This was formalised in the Statute of Rhuddlan in 1284, by which Wales became part of the Kingdom of England by the Laws in Wales Acts 1535–1542. Wales shared a legal identity with England as the joint entity originally called England and later England and Wales.

An epidemic of catastrophic proportions, the Black Death first reached England in the summer of 1348. The Black Death is estimated to have killed between a third and two-thirds of Europe's population. England alone lost as much as 70% of its population, which passed from seven million to two million in 1400. The plague repeatedly returned to haunt England throughout the 14th to 17th centuries.[19] The Great Plague of London in 1665–1666 was the last plague outbreak.[20]

Reformation

During the English Reformation in the 16th century, the external authority of the Roman Catholic Church in England was abolished and replaced with Royal Supremacy and ultimately describes the establishment of a Church of England, outside the Roman Catholic Church, under the Supreme Governance of the English monarch. The English Reformation differed from its European counterparts in that it was a political, rather than purely theological, dispute at root.[21] The break with Rome started in the reign of Henry VIII.

The English Reformation paved the way for the spread of Anglicanism in the church and other institutions.

Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations that took place between Parliamentarians and Royalists from 1642 until 1651. The first (1642–1645) and second (1648–1649) civil wars pitted the supporters of King Charles I against the supporters of the Long Parliament, while the third war (1649–1651) saw fighting between supporters of King Charles II and supporters of the Rump Parliament. The Civil War ended with the Parliamentary victory at the Battle of Worcester on 3 September 1651.

The Civil War led to the trial and execution of Charles I, the exile of his son Charles II and the replacement of the English monarchy with the Commonwealth of England (1649–1653) and then with a Protectorate (1653–1659) : the personal rule of Oliver Cromwell. After a brief return to Commonwealth rule, in 1660 The Crown was restored and Charles II accepted Convention Parliament's invitation to return to England. During the interregnum the monopoly of the Church of England on Christian worship in England came to an end, and the victors consolidated the already-established Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. Constitutionally, the wars established a precedent that British monarchs could not govern without the consent of Parliament although this would not be cemented until the Glorious Revolution later in the century.

Great Britain and the United Kingdom

|

|

| England | United Kingdom |

The Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland remained separate countries until 1707, when under the Acts of Union both England and Scotland lost their individual political – although not legal – identities when they united as the Kingdom of Great Britain. Ireland later joined this union to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland changed its name to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland in 1927 to reflect its reduced territory following the secession of southern Ireland as the Irish Free State in 1922.

Throughout these changes, England (including Wales) retained a separate legal identity from its partners, with a separate legal system (English law) from those in Northern Ireland (Northern Ireland law) and Scotland (Scots law). (See subdivisions of the United Kingdom)

Wales was made part of the Kingdom of England by the Statute of Rhuddlan in 1284, and it was legally incorporated into England by the Wales and Berwick Act 1746, making laws passed in England automatically applicable to Wales. This was reversed by the Welsh Language Act 1967, which gave Wales a separate identity from England. Since then, legal and political terminology refers to "England and Wales". The county of Monmouthshire has long been an ambiguous area, its legal identity passing between England and Wales at various periods. In the Local Government Act 1972 it was made part of Wales.

The Wales and Berwick Act 1746 also refers to the formerly Scottish burgh of Berwick-upon-Tweed. The border town changed hands several times and was last conquered by England in 1482, but was not officially incorporated into England. Berwick is regarded today as part of England.

The Isle of Man and the Channel Islands are Crown dependencies and are not part of England or of the United Kingdom.

Politics

There has not been a Government of England since 1707, when the Kingdom of England merged with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, although both kingdoms have been ruled by a single monarch since 1603. Before the Acts of Union of 1707, England was ruled by a monarch and the Parliament of England.

The Scottish and Welsh governing institutions were created by the UK parliament with support from the majority of people of Scotland and Wales in referenda in 1997 and are not independent of the rest of the United Kingdom. However, this gave each country a separate political entity that left England as the only part of Britain directly ruled in nearly all matters by the British government in London. In Cornwall, a region of England claiming a distinct national identity, there has been a campaign for a Cornish assembly along Welsh lines by nationalist parties such as Mebyon Kernow.

Because Westminster is the UK parliament but also votes on local English matters devolution of national matters to parliament/assemblies in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland has refocused attention on a long-standing anomaly called the West Lothian question. The "Question" is that there is no convention or rule whereby Scottish MPs are barred from voting on issues relating only to England and Wales in the post devolution era.

Welsh devolution has removed the anomaly for Wales, but highlighted the anomaly for England: Scottish and Welsh MPs can vote on English issues, but purely Scottish and Welsh issues are debated in Scotland and Wales, not at Westminster; in fact Scottish MPs are even unable to vote on such issues affecting their own constituencies. This problem is exacerbated by an over-representation of Scottish MPs in the government, sometimes referred to as the Scottish mafia; as of September 2006, seven of the twenty-three Cabinet members are Scottish, including the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Home Secretary and Defence Secretary. In addition, Scotland traditionally benefited from moderate malapportionment in its favour, increasing its representation to a degree disproportionate to its population. In 2004 the Scottish Parliament (Constituencies) Act 2004 was passed which rectified this to a degree, reducing the number of MPs representing Scottish constituencies from 73 to 59 and brought the number of voters per constituency closer to that in England. This change was implemented in the 2005 General Election.

In terms of national administration, England's affairs are managed by a combination of the UK government, the UK parliament, England-specific quangos such as English Heritage, and the mostly unelected Regional Assemblies.

There are calls for a devolved English Parliament, and certain English parties go further by calling for the dissolution of the Union entirely.[22][23] However, the approach favoured by the current Labour government was (on the basis that England is too large to be governed as a single sub-state entity) to propose the devolution of power to the Regions of England. Lord Falconer claimed a devolved English parliament would dwarf the rest of the United Kingdom.[24] Referendums would decide whether people wanted to vote for directly elected regional assemblies to watch over the work of the non-elected Regional Development Agencies.

During the campaign, a common criticism of the proposals was that England did not need "another tier of bureaucracy".[25] On the other hand, many said that they were not decentralising enough, and amounted not to devolution, but to little more than local government reorganisation, with no real power being removed from central government, and no real power given to the regions, which would not even gain the limited powers of the Welsh Assembly, much less the tax-varying and legislative powers of the Scottish Parliament (but Welsh powers are now being expanded). They said that power was simply re-allocated within the region, with little new resource allocation and no real prospects of Assemblies being able to change the pattern of regional aid. Late in the process, responsibility for regional transport was added to the proposals. This was perhaps crucial in the North East, where resentment at the Barnett Formula, which delivers greater public spending per head to adjacent Scotland, was a significant impetus for the North East devolution campaign. However, a referendum on this issue in North East England on 4 November 2004 rejected this proposal, and plans for referendums in other Regions were shelved.

Subdivisions

Historically, the highest level of local government in England was the county. These have their origin in the shires, the subdivisions of the kingdom of Wessex, which were extended over the rest of England as Wessex expanded to unite the country in the ninth and tenth centuries. Some of these new shires, particularly in the south-east of England, retained the extent and names of the kingdoms or subdivisions of kingdoms that had existed there before, such as Sussex and Kent, but most were new creations, named after their principal town with the suffix "-shire" added, for example Warwickshire from Warwick. In the far north of England, the system took longer to become regularised and County Durham, Northumberland, Cumberland and Westmorland emerged after the Norman Conquest. The counties each had a county town.

Since these historical county lines were drawn up before the Industrial Revolution and the mass urbanisation of England, the changes in the distribution of population and the demands on local administration resulting from those developments have led to a series of local government reorganisations since the latter part of the 19th century. The solution to the emergence of large urban areas was the creation of large metropolitan counties centred on cities (an example being Greater Manchester). The creation of unitary authorities, where districts gained the administrative status of a county, began with the 1990s reform of local government. Today, some confusion exists between the ceremonial counties (which do not necessarily form an administrative unit) and the metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties.

Non-metropolitan counties (or "shire counties") are divided into one or more districts. At the lowest level, England is divided into parishes, although these are not found everywhere (many urban areas for example are unparished). Parishes are prohibited from existing in Greater London.

England is now also divided into nine regions, which do not have an elected authority and exist to co-ordinate certain local government functions across a wider area. London is an exception, however, and is the one region that now has a representative authority as well as a directly elected mayor. The 32 London boroughs and the City of London Corporation remain the local form of government in the city.

Geography

England comprises the central and southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain, plus offshore islands of which the largest is the Isle of Wight. It is bordered to the north by Scotland and to the west by Wales. It is closer to continental Europe than any other part of Britain, divided from France only by a 52 km (24 statute mile or 21 nautical mile)[26] sea gap. The Channel Tunnel, near Folkestone, directly links England to the European mainland. The English/French border is halfway along the tunnel.[27]

Much of England consists of rolling hills, but it is generally more mountainous in the north with a chain of low mountains, the Pennines, dividing east and west. Other hilly areas in the north and Midlands are the Lake District, the North York Moors, and the Peak District. The approximate dividing line between terrain types is often indicated by the Tees-Exe line. To the south of that line, there are larger areas of flatter land, including East Anglia and the Fens, although hilly areas include the Cotswolds, the Chilterns, the North and South Downs, Dartmoor and Exmoor.

The largest natural harbour in England is at Poole, on the south-central coast. Some regard it as the second largest harbour in the world, after Sydney, Australia, although this fact is disputed (see harbours for a list of other large natural harbours).

Climate

England has a temperate climate, with plentiful rainfall all year round, although the seasons are quite variable in temperature. However, temperatures rarely fall below −5 °C (23 °F) or rise above 30 °C (86 °F). The prevailing wind is from the south-west, bringing mild and wet weather to England regularly from the Atlantic Ocean. It is driest in the east and warmest in the south, which is closest to the European mainland. Snowfall can occur in winter and early spring, although it is not that common away from high ground.

The highest temperature recorded in England is 38.5 °C (101.3 °F) on August 10, 2003 at Brogdale, near Faversham, in Kent.[28] The lowest temperature recorded in England is −26.1 °C (−15.0 °F) on January 10, 1982 at Edgmond, near Newport, in Shropshire.[29]

Major rivers

- Severn (the longest river and largest river basin in Great Britain)

- Tees

- Thames

- Trent

- Humber

- Tyne

- Wear

- Ribble

- Ouse

- Mersey

- Dee

- Aire

- Avon

- Medway

Major conurbations

London is by far the largest urban area in England and one of the largest and busiest cities in the world. Other cities, mainly in central and northern England, are of substantial size and influence. The list of England's largest cities or urban areas is open to debate because, although the normal meaning of city is "a continuously built-up urban area", this can be hard to define, particularly because administrative areas in England often do not correspond with the limits of urban development, and many towns and cities have, over the centuries, grown to form complex urban agglomerations. Various definitions of cities can be used. For the official definition of a UK (and therefore English) city, see City status in the United Kingdom.

-

Birmingham

-

Manchester

-

Liverpool's skyline

-

Leeds - Bridgewater Place

According to the ONS urban area populations for continuous built-up areas, these are the 15 largest conurbations (population figures from the 2001 census):

Economics

England's economy is the second largest in Europe and the fifth largest in the world. It follows the Anglo-Saxon economic model. England's economy is the largest of the four economies of the United Kingdom, with 100 of Europe's 500 largest corporations based in London.[32] As part of the United Kingdom, England is a major centre of world economics. One of the world's most highly industrialised countries, England is a leader in the chemical and pharmaceutical sectors and in key technical industries, particularly aerospace, the arms industry and the manufacturing side of the software industry.

London exports mainly manufactured goods and imports materials such as petroleum, tea, wool, raw sugar, timber, butter, metals, and meat.[33] England exported more than 30,000 tons of beef last year, worth around £75,000,000, with France, Italy, Greece, the Netherlands, Belgium and Spain being the largest importers of beef from England.[34]

The central bank of the United Kingdom, which sets interest rates and implements monetary policy, is the Bank of England in London. London is also home to the London Stock Exchange, the main stock exchange in the UK and the largest in Europe. London is one of the international leaders in finance[35] and the largest financial centre in Europe.

Traditional heavy and manufacturing industries have declined sharply in England in recent decades, as they have in the United Kingdom as a whole. At the same time, service industries have grown in importance. For example, tourism is the sixth largest industry in the UK, contributing 76 billion pounds to the economy. It employs 1,800,000 full-time equivalent people—6.1% of the working population (2002 figures).[36] The largest centre for tourism is London, which attracts millions of international tourists every year.

As part of the United Kingdom, England's official currency is the Pound Sterling (also known as the British pound or GBP).

Demography

This section may contain material not related to the topic of the article and should be moved to United Kingdom instead. |

With 50,431,700 inhabitants, or 84% of the UK's total,[37] England is the most populous nation in the United Kingdom; as well as being the most ethnically diverse. England would have the fourth largest population in the European Union and would be the 25th largest country by population if it were a sovereign state.

The country's population is 'ageing', with a declining percentage of the population under age 16 and a rising one of over 65. Population continues to rise and in every year since 1901, with the exception of 1976, there have been more births than deaths.[38] England is one of the most densely populated countries in Europe, with 383 people per square kilometre (992/sq mi) ,[39] making it second only to the Netherlands.

The generally accepted view is that the ethnic background of the English populace, before 19th- and 20th-century immigration, was a mixed European one deriving from historical waves of Celtic, Roman, Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Norman invasions, along with the possible survival of pre-Celtic ancestry. Genetic studies have shown that the modern-day English gene pool contains more than 50% Germanic Y-chromosomes.[40][41]

The economic prosperity of England has also made it a destination for economic migrants from Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. This was particularly true during the Industrial Revolution.

Since the fall of the British Empire, many denizens of former colonies have migrated to Britain including the Indian sub-continent and the British Caribbean. A BBC-published report of the 2001 census, by the Institute for Public Policy Research stated that the vast majority of immigrants settled in London and the South East of England. The largest groups of residents born in other countries were from the Republic of Ireland, India, Pakistan, Germany, and the Caribbean. Although Germany was high on the list, this was mainly the result of children being born to British forces personnel stationed in that country.[42]

About half the population increase between 1991 and 2001 was due to foreign-born immigration. In 2004 the number of people who became British citizens rose to a record 140,795—a rise of 12% on the previous year. The number had risen dramatically since 2000. The overwhelming majority of new citizens come from Africa (32%) and Asia (40%), the largest two groups being people from India and Pakistan.[43] One in five babies in the UK are born to immigrant mothers, according to official statistics released in 2007. 21.9% of all births in the UK in 2006 were to mothers born outside the United Kingdom compared with just 12.8% in 1995.[44]

In 2006, an estimated 591,000 migrants[45][46] arrived to live in the UK for at least a year, while 400,000 people emigrated from the UK for a year or more, with Australia, Spain, France, New Zealand and the U.S. most popular destinations.[47][48][49] Largest group of arrivals were people from the Indian subcontinent who accounted for two-thirds of net immigration, mainly fuelled by family reunion.[50] One in six were from Eastern European countries. They were outnumbered by immigrants from New Commonwealth countries.[51]

The European Union allows free movement between the member states. While France and Germany put in place controls to curb Eastern European migration, the UK and Ireland did not impose restrictions. Following Poland's entry into the EU in May 2004 it is estimated that by the start of 2007 about 375,000 Poles have registered to work in the UK, although the total Polish population in the UK is believed to be 750,000. Many Poles work in seasonal occupations and a large number is likely to move back and forth including between Ireland and other EU Western nations. A quarter of Eastern European migrants, often young and well-educated, plan to stay in Britain permanently. Most of them had originally intended to go home but have changed their minds after living there.[52]

Culture

England has a vast and influential culture that encompasses elements both old and new. The modern culture of England is sometimes difficult to identify and separate clearly from the culture of the wider United Kingdom, so intertwined are its composite nations. However, the traditional and historic culture of England is more clearly defined.

English Heritage is a governmental body with a broad remit of managing the historic sites, artefacts and environments of England. London's British Museum, British Library and National Gallery contain some of the finest collections in the world.

The English have played a significant role in the development of the arts and sciences. Many of the most important figures in the history of modern western scientific and philosophical thought were either born in, or at one time or other resided in, England. Major English thinkers of international significance include scientists such as Sir Isaac Newton, Francis Bacon, Charles Darwin and New Zealand-born Ernest Rutherford, philosophers such as John Locke, John Stuart Mill, Bertrand Russell and Thomas Hobbes, and economists such as David Ricardo, and John Maynard Keynes. Karl Marx wrote most of his important works, including Das Kapital, while in exile in Manchester, and the team that developed the first atomic bomb began their work in England, under the wartime codename tube alloys.

Architecture

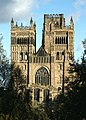

England has played a significant part in the advancement of Western architecture. It is home to some of the finest mediaeval castles and forts in the world, including Warwick Castle, the Tower of London and Windsor Castle (the largest inhabited castle in the world and the oldest in continuous occupation). It is known for its numerous grand country houses, and for its many mediaeval and later churches and cathedrals.

English architects have contributed to many styles over the centuries, including Tudor architecture, English Baroque, the Georgian style and Victorian movements such as Gothic Revival. Among the best-known contemporary English architects are Norman Foster and Richard Rogers.

Cuisine

Although highly regarded in the Middle Ages, English cuisine later became a source of fun among Britain's French and European neighbours, being viewed until the late 20th century as crude and unsophisticated by comparison with continental tastes. However, with the influx of non-European immigrants (particularly those of south and east Asian origins) from the 1950s onwards, the English diet was transformed. Indian and Chinese cuisine in particular were absorbed into British culinary life, with restaurants and takeaways appearing in almost every town in Britain, and 'going for an Indian' becoming a regular part of British social life. A distinct hybrid food style composed of dishes of Asian origin, but adapted to British tastes, emerged and was subsequently exported to other parts of the world. Many of the well-known Indian dishes in the western world, such as Tikka Masala and Balti, are in fact dishes of this sort.

Dishes forming part of the old tradition of English food include:

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

Engineering and innovation

As birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, England was home to many significant inventors during the late 18th and early 19th century. Famous English engineers include Isambard Kingdom Brunel, best known for the creation of the Great Western Railway, a series of famous steamships, and numerous important bridges, hence revolutionising public transport and modern-day engineering.

Other notable English figures in the fields of engineering and innovation include:

- Richard Arkwright – inventor of the first industrial spinning machine

- Charles Babbage – inventor of the first computer (in the 19th century)

- Tim Berners-Lee – inventor of the World Wide Web, http, html, and many of the other technologies on which the Web is based

- James Blundell – who performed the first blood transfusion

- Hubert Cecil Booth – inventor of the Vacuum cleaner

- Edwin Beard Budding – inventor of the lawnmower

- George Cayley – inventor of the seat belt

- Christopher Cockerell – inventor of the hovercraft

- John Dalton – pioneer of atomic theory

- James Dyson – inventor of the Dual Cyclone bagless vacuum cleaner

- Michael Faraday – inventor of the electric motor

- Thomas Fowler – inventor of the thermosiphon

- Robert Hooke – Hooke's law of elasticity

- E. Purnell Hooley – inventor of tarmac

- Thomas Newcomen – inventor of the first practical steam engine

- Isaac Newton – defining Universal gravitation, Newtonian mechanics, Infinitesimal calculus

- Stephen Perry – inventor of the rubber band

- Thomas Savery – inventor of the steam engine

- Percy Shaw – inventor of the "cat's eye" road safety device

- George Stephenson and Robert Stephenson – railway pioneers (father and son)

- Joseph Swan – developer of the light bulb

- Richard Trevithick – builder of the earliest steam locomotive

- Jethro Tull – inventor of the seed drill

- Alan Turing and Tommy Flowers – inventors of the modern computer and its associated concepts and technologies

- Frank Whittle – inventor of the jet engine

- Joseph Whitworth – inventor of many of the modern techniques and technologies of precision engineering

Folklore

English folklore is rich and diverse. Many of the land's oldest legends share themes and sources with the Celtic folklore of Wales, Scotland and Ireland, a typical example being the legend of Herne the Hunter, which shares many similarities with the traditional Welsh legend of Gwyn ap Nudd.

Successive waves of pre-Norman invaders and settlers, from the Romans onwards, via Saxons, Jutes, Angles, Norse to the Norman Conquest have all influenced the myth and legend of England. Some tales, such as that of The Lambton Wyrm show a distinct Norse influence, while others, particularly some of the events and characters associated with the Arthurian legends show a distinct Romano-Gaulic slant.[53]

Among the most famous English folk-tales are the legends of King Arthur, although it would be wrong to regard these stories as purely English in origin as they also concern Wales and, to a lesser extent, Ireland and Scotland. They should therefore be considered as part of the folklore of the British Isles as a whole.

Post-Norman stories include the tales of Robin Hood, which exists in many forms, and stories of other folk heroes such as Hereward the Wake and Fulk FitzWarin who, although being based on historical characters, have grown to become legends in their own right.

Literature

The English language has a rich and prominent literary heritage. England has produced a wealth of significant literary figures including playwrights William Shakespeare, Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson, John Webster, as well as writers Daniel Defoe, Henry Fielding, Jane Austen, William Makepeace Thackeray, Charlotte Brontë, Emily Brontë, J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Dickens, Mary Shelley, H. G. Wells, George Eliot, Rudyard Kipling, D. H. Lawrence, E. M. Forster, Virginia Woolf, George Orwell and Harold Pinter. Others, such as J. K. Rowling, Enid Blyton and Agatha Christie have been among the best-selling novelists of the last century.

Among the poets, Geoffrey Chaucer, Edmund Spenser, Sir Philip Sydney, Thomas Kyd, John Donne, Andrew Marvell, Alexander Pope, William Wordsworth, Lord Byron, John Keats, John Milton, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, T. S. Eliot (American-born, but a British subject from 1927) and many others remain read and studied around the world. Among men of letters, Samuel Johnson, William Hazlitt and George Orwell are some of the most famous. England continues to produce writers working in all branches of literature, and in a wide range of styles; contemporary English literary writers attracting international attention include Martin Amis, Julian Barnes and Zadie Smith.

Music

Composers from England have not achieved recognition as broad as that earned by their literary counterparts, and, particularly during the 19th century, were overshadowed in international reputation by other European composers; however, many works of earlier composers such as Thomas Tallis, William Byrd, and Henry Purcell are still frequently performed throughout the world today. A revival of England's musical status began during the 20th century with the prominence of composers such as Edward Elgar, Gustav Holst, William Walton, Eric Coates, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Frederick Delius and Benjamin Britten.

In popular music, however, English bands and solo artists have been cited as the most influential and best-selling musicians of all time. Acts such as The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, Elton John, Queen, and The Rolling Stones are among the highest selling in the world.[57] England is also credited with being the birthplace of many musical genres and movements such as hard rock, British invasion, heavy metal, britpop, glam rock, drum and bass, progressive rock, punk rock, gothic rock, shoegazing, acid house, UK garage, trip hop and dubstep.

Science and philosophy

Prominent English figures from the field of science and mathematics include Sir Isaac Newton, Michael Faraday, J. J. Thomson, Charles Babbage, Charles Darwin, Stephen Hawking, Christopher Wren, Alan Turing, Francis Crick, Joseph Lister, Tim Berners-Lee, Andrew Wiles and Richard Dawkins. Some experts claim that the earliest concept of a Metric system was invented by John Wilkins, first secretary of the Royal Society in 1668.[58]

England played a major role in the development of Western philosophy, particularly during the Enlightenment. Jeremy Bentham, leader of the Philosophical Radicals, and his school are recognised as the men who unknowingly laid down the doctrines for Socialism.[59] Bentham's impact on English law is also considerable. Aside from Bentham, major English philosophers include Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Thomas Paine, John Stuart Mill, Bernard Williams and Bertrand Russell.

Sport

Several modern sports were codified in England during the 19th century, among them cricket, rugby union and rugby league, football, tennis and badminton. Of these, association football, rugby and cricket remain the country's most popular spectator sports. England contains more UEFA 5 star and 4 star rated stadia than any other country, and is home to some of the sport's top clubs. Among these, Aston Villa, Liverpool FC, Manchester United and Nottingham Forest have won the European Cup. The England national football team are considered one of the game's superpowers (currently ranked 11th by FIFA[60] and 8th by Elo[61]), having won the World Cup in 1966 when it was hosted in England. Since then, however, they have failed to reach a final of a major international tournament, although they reached the semi-finals of the World Cup in 1990 and the quarter-finals in 2002 and 2006 and Euro 2004.

More recently, England failed to qualify for the Euro 2008 championships when it lost 2–3 to Croatia on November 21, 2007 in its final qualifying match. England, playing at home at Wembley Stadium, needed just a draw to ensure qualification. This is the first time since the 1994 World Cup that England has failed to qualify for a major football championship and first time since 1984 that the team will miss the Euros. On November 22, 2007, the day after the defeat to Croatia, England fired its football coach, Steve McClaren and his assistant Terry Venables, ostensibly as a direct consequence of its failure to qualify for Euro 2008.[62]

The England national rugby union team and England cricket team are often among the best performing in the world, with the rugby union team winning the 2003 Rugby World Cup (and finishing as runners-up in 2007), and the cricket team winning The Ashes in 2005, and being ranked the second best Test nation in the world. Rugby union clubs such as Leicester Tigers, London Wasps and the Northampton Saints have had success in the Europe-wide Heineken Cup. At rugby league, the England national rugby league team are to compete more regularly after 2006, when England will become a full test nation in lieu of the Great Britain national rugby league team, when that team is retired after the 2006 Rugby League Tri-Nations.

Sport England is the governing body responsible for distributing funds and providing strategic guidance for sporting activity in England.

The 2012 Summer Olympics are to be hosted by London, England. It will run from 26 July to 12 August 2012. London will become the first city to have hosted the modern Olympic Games three times, having previously done so in 1908 and 1948.

Language

Language

As its name suggests, the English language, today spoken by hundreds of millions of people around the world, originated as the language of England, where it remains the principal tongue today (although not officially designated as such). An Indo-European language in the Anglo-Frisian branch of the Germanic family, it is closely related to Scots and the Frisian languages. As the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms merged into England, "Old English" emerged; some of its literature and poetry has survived.

Used by aristocracy and commoners alike before the Norman Conquest (1066), English was displaced in cultured contexts under the new regime by the Norman French language of the new Anglo-Norman aristocracy. Its use was confined primarily to the lower social classes while official business was conducted in a mixture of Latin and French. Over the following centuries, however, English gradually came back into fashion among all classes and for all official business except certain traditional ceremonies, some of which survive to this day. Although, Middle English, as it had by now become, showed many signs of French influence, both in vocabulary and spelling. During the Renaissance, many words were coined from Latin and Greek origins; and more recent years, Modern English has extended this custom, willing to incorporate foreign-influenced words.

It is most commonly accepted that—thanks in large part to the British Empire, and now the United States—the English language is now the world's unofficial lingua franca,[63] while English common law is also the foundation of many legal systems throughout the English-speaking countries of the world.[64] English language learning and teaching is an important economic sector, including language schools, tourism spending, and publishing houses.

Additional languages

UK legislation does not recognise any language as being official,[65] but English is the only language used in England for general official business. The other national languages of the UK (Welsh, Irish, Scots and Scottish Gaelic) are confined to their respective nations, except Welsh to some degree.

The only non-Anglic native spoken language in England is the Cornish language, a Celtic language spoken in Cornwall, which became extinct in the 19th century but has been revived and is spoken in various degrees of fluency, currently by about 2,000 people.[66] This has no official status (unlike Welsh) and is not required for official use, but is nonetheless supported by national and local government under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Cornwall County Council has produced a draft strategy to develop these plans. There is, however, no programme as yet for public bodies to actively promote the language. Scots is spoken by some adjacent to the Anglo-Scottish Border, and Welsh is still spoken by some natives around Oswestry, Shropshire, on the Welsh border.

Most deaf people within England speak British sign language (BSL), a sign language native to Britain. The British Deaf Association estimates that 250,000 people throughout the UK speak BSL as their first or preferred language,[67] but does not give statistics specific to England. BSL is not an official language of the UK and most British government departments and hospitals have limited facilities for deaf people. The BBC broadcasts several of its programmes with BSL interpreters.

Different languages from around the world, especially from the former British Empire and the Commonwealth of Nations, have been brought to England by immigrants. Many of these are widely spoken within ethnic minority communities, with Bengali, Hindi, Sinhala, Tamil, Punjabi, Urdu, Gujarati, Polish, Greek, Turkish and Cantonese being the most common languages that people living in Britain consider their first language. These are often used by official bodies to communicate with the relevant sections of the community, particularly in large cities, but this occurs on an "as needed" basis rather than as the result of specific legislative ordinances.

Other languages have also traditionally been spoken by minority populations in England, including Romany.

Despite the relatively small size of the nation, there are many distinct English regional accents. Those with particularly strong accents may not be easily understood elsewhere in the country. Use of foreign non-standard varieties of English (such as Caribbean English) is also increasingly widespread, mainly because of the effects of immigration.

Religion

Due to immigration in the past decades, there is an enormous diversity of religious belief in England, as well as a growing percentage that have no religious affiliation. Levels of attendance in various denominations have begun to decline[citation needed]. England is classed largely as a secular country even allowing for the following affiliation percentages : Christianity: 71.6%, Islam: 3.1%, Hindu: 1.1%, Sikh: 0.7%, Jewish: 0.5%, and Buddhist: 0.3%, No Faith: 22.3%.[68] The EU Eurobarometer poll of 2005 shows that only 38% of people in the UK believe in a god, while 40% believe in "some sort of spirit or life force" and 20% do not believe in either.[69]

Christianity

Christianity reached England through missionaries from Scotland and from Continental Europe; the era of St. Augustine (the first Archbishop of Canterbury) and the Celtic Christian missionaries in the north (notably St. Aidan and St. Cuthbert). The Synod of Whitby in 664 ultimately led to the English Church being fully part of Roman Catholicism. Early English Christian documents surviving from this time include the 7th-century illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels and the historical accounts written by the Venerable Bede. England has many early cathedrals, most notably York Minster (1080), Durham Cathedral (1093) and Salisbury Cathedral (1220), In 1536, the Church was split from Rome over the issue of the divorce of King Henry VIII from Catherine of Aragon. The split led to the emergence of a separate ecclesiastical authority, and later the influence of the Reformation, resulting in the Church of England and Anglicanism. Unlike the other three constituent countries of the UK, the Church of England is an established church (although the Church of Scotland is a 'national church' recognised in law).

The 16th-century break with Rome under the reign of King Henry VIII and the Dissolution of the Monasteries had major consequences for the Church (as well as for politics). The Church of England remains the largest Christian church in England; it is part of the Anglican Communion. Many of the Church of England's cathedrals and parish churches are historic buildings of significant architectural importance.

Other major Christian Protestant denominations in England include the Methodist Church, the Baptist Church and the United Reformed Church. Smaller denominations, but not insignificant, include the Religious Society of Friends (the "Quakers") and the Salvation Army—both founded in England. There are also Afro-Caribbean Churches, especially in the London area.

The Roman Catholic Church re-established a hierarchy in England in the 19th century. Attendances were considerably boosted by immigration, especially from Ireland and more recently Poland.

The Church of England is still the official state church.

Other religions

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, immigration from many colonial countries, often from South Asia and the Middle East have resulted in a considerable growth in Islam, Sikhism and Hinduism in England. Cities and towns with large Muslim communities include Birmingham, Blackburn, Coventry, Bolton, Bradford, Leicester, London, Luton, Manchester, Oldham and Sheffield. Cities and towns with large Sikh communities include London, Slough, Staines, Hounslow, Southall, Reading, Ilford, Barking, Dagenham, Leicester, Leeds, Birmingham, Wolverhampton and others.

The Jewish community in England is mainly in the Greater London area, particularly the north west suburbs such as Golders Green;[70] although Manchester, Leeds and Gateshead also have significant Jewish communities.[71][72]

Education

There is a long history of the promotion of education in England in schools, colleges and universities. England is home to the oldest existing schools in the English speaking world: The King's School, Canterbury and The King's School, Rochester, believed to be founded in the 6th and 7th century respectively. At least eight existing schools in England were founded in the first millennium. Most of these ancient institutions are fee-paying schools, however there are also early examples of state schools in England, most notably Beverley Grammar School founded in 700. State and private schools and colleges have continued side by side since that time. Other notable English schools include Winchester College (founded 1382), Eton College (1440), St Paul's London, (1509)Tonbridge School (1553), Rugby School (1567), Harrow School (1572), Charterhouse School (1611), and Sherborne School, which was granted an official charter in 1550, but due to its attachment to Sherborne Abbey, which has been a place of scholarship since 705, it stakes a good claim to being among the oldest educational establishments in the country, and Radley College (1847). The oldest surviving girls' school in England is Red Maids' School founded in 1634. England is also home to the two oldest universities in the English speaking world: Oxford University (12th century) and Cambridge University (early 13th century). More than 90 universities are in England and many of these (most notably the universities of Oxford, Cambridge and London) consist of autonomous colleges, many of which are world famous in their own right, for example University College, Oxford (founded 1249), Peterhouse, Cambridge (1284) Imperial College London and the London School of Economics (1895).

The education system in England is run by the Department for Children, Schools and Families. The education is split into two main types; State schools funded through taxation and free to all, and private schools, which provide a paid-for education on top of taxes (also confusingly known as "Public" or "Independent" schools).

Education is the responsibility of Department for Children, Schools and Families at national level and, in the case of publicly funded compulsory education, of Local Education Authorities. The education structures for Wales and Northern Ireland are broadly similar to the English system, but there are significant differences of emphasis in the depth and breadth of teaching objectives in Scotland. Traditionally the English system emphasises depth of education, whereas the Scottish system emphasises breadth.

The extraordinary level of education in England is maintained by regular Government inspections of State run schools, and Ofsted inspections of private schools.

Transport

London Heathrow Airport is England's largest airport, the largest airport by traffic volume in Europe and one of the world's busiest airports, and London Gatwick Airport is England's second largest, followed by Manchester Airport. Other major airports include London Stansted Airport in Essex, about 50 kilometres (30 mi) north of London, Coventry Airport and Birmingham International Airport.

The growth in private car ownership in the latter half of the 20th century led to major road-building programmes. Important trunk roads built include the A1 Great North Road from London to Newcastle and Edinburgh, and the A580 "East Lancs." road between Liverpool and Manchester. The M6 motorway is the country's longest motorway running from Rugby through North West England to the Scottish border. Other major roads include the M1 motorway from London to Leeds up the east of the country, the M25 motorway which encircles London, the M60 motorway which encircles Manchester, the M4 motorway from London to South Wales, the M62 motorway from Liverpool to Manchester and Yorkshire, and the M5 motorway from Birmingham to Bristol and the South West.

Most of the British National Rail network of 16,116 route km (10,072 route miles) lies in England. Urban rail networks are also well developed in London and several other cities, including the Manchester Metrolink and the London Underground. The London Underground is the oldest and most extensive underground railway in the world, and as of 2007 consists of 407 km (253 mi) of line[73] and serves 275 stations.

There are around 7,100 km (4,400 mi) of navigable waterways in England, of which roughly half is owned by British Waterways. An estimated 165 million journeys are made by people on Britain's waterways annually. The Thames is the major waterway in England, with imports and exports focused at Tilbury, one of the three major ports in the UK. Ports in the UK handled over 560 million tonnes of domestic and international freight in 2005.[74]

The government department overseeing transport is the Department for Transport.

People

The ancestry of the English, considered as an ethnic group, is mixed; it can be traced to the mostly Celtic Romano-Britons,[75] to the eponymous Anglo-Saxons,[76] the Danish-Vikings[77] that formed the Danelaw during the time of Alfred the Great and the Normans,[78][79] among others. The 19th and 20th centuries, furthermore, brought much new immigration to England.

Ethnicity aside, the simplest view is that an English person is someone who was born in England and holds British nationality, regardless of his or her racial origin. It has, however, been a notoriously complicated, emotive and controversial identity to delimit. Centuries of English dominance within the United Kingdom has created a situation where to be English is, as a linguist would put it, an "unmarked" state. The English frequently include themselves and their neighbours in the wider term of "British", while the Scots and Welsh tend to be more forward about referring to themselves by one of those more specific terms.[80] This reflects a more subtle form of English-specific patriotism in England; St George's Day, the country's national day, is barely celebrated. The celebrations have increased year on year over the past five years.[81]

Modern celebration of English identity is often found around its sports, one field in which the British Home Nations often compete individually. The English Association football team, rugby union team and cricket team often cause increases in the popularity of celebrating Englishness.

Nomenclature

The country is named after the Angles, one of several Germanic tribes who settled the country in the fifth and sixth centuries. There are two distinct linguistic patterns for the name of the country.

|

Most European languages use names similar to "England":

|

The Celtic names are quite different, referring to the Saxons, another family of Germanic tribes that arrived at about the same time as the Angles.

The names in Asian languages:

Names in other languages:

|

Alternative names include:

- The slang "Blighty", from the Hindustani "bila yati" meaning "foreign" (which coincidentally resembles "Britain")

- "Albion", an ancient name, supposedly referring to the white (Latin alba) cliffs of Dover. Although it refers to the whole island of Great Britain, it is occasionally, and incorrectly, used for England. Following the Roman conquest of Britain, the term contracted to mean only the area north of Roman control and is today a relative of Alba, the Celtic languages name for Scotland.

- More poetically, England has been called "this sceptred isle...this other Eden" and "this green and pleasant land", quotations respectively from the poetry of William Shakespeare (in Richard II) and William Blake (And did those feet in ancient time).

Slang terms sometimes used for the people of England include "Sassenachs" or "Sasanachs" (from the Scots Gaelic and Irish Gaelic respectively, both originally meaning "Saxon", and originally a Scottish Highland term for Lowland Scots), "Limeys" (in reference to the citrus fruits carried aboard English sailing vessels to prevent scurvy) and "Pom/Pommy" (used in Australian English and New Zealand English), but these may be perceived as offensive. Also see alternative words for British.

National symbols, insignia and anthems

The two main traditional symbols of England are the St George's Cross (the English flag), and the Three Lions coat of arms.

Other national symbols exist, but have varying degrees of official usage, such as the oak tree and the rose.

England's National Day is St George's Day (Saint George being the patron saint), which is on 23 April.[82]

-

A one-pound coin with an English oak tree

-

A one-pound coin with the three lions of England

-

Saint George and the Dragon, Paolo Uccello, c. 1470. This small dragon has the look of a griffin or a wyvern.

-

The English rose at the border of Wales and England

St George's Cross

The St George's Cross is a red cross on a white background and is the national flag of England.

It is believed to have been adopted for the uniform of English soldiers during the Crusades of the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries.[83] From about 1277 it became the national flag of England. St George's Cross was originally the flag of Genoa and was adopted by England and the City of London in 1190 for their ships entering the Mediterranean to benefit from the protection of the powerful Genoese fleet. The maritime Republic of Genoa was rising and going to become, with its rival Venice, one of the most important powers in the world. The English Monarch paid an annual tribute to the Doge of Genoa for this privilege. The cross of St George would become the official Flag of England.

A red cross acted as a symbol for many Crusaders in the 12th and 13th centuries. It became associated with St George and England, along with other countries and cities (such as Georgia, Milan and the Republic of Genoa), which claimed him as their patron saint and used his cross as a banner. It remained in national use until 1707, when the Union Flag (also known as the Union Jack, especially at sea) which English and Scottish ships had used at sea since 1606, was adopted for all purposes to unite the whole of Great Britain under a common flag. The flag of England no longer has much of an official role, but it is widely flown by Church of England properties and at sporting events.

Until recently, the flag was not commonly flown in England with the British Union Flag being used instead. This was certainly evident at the 1966 Football World Cup when English fans predominantly flew the latter. However, since devolution in the United Kingdom, the St George Cross has experienced a growth in popularity and is now the predominant flag used in English sporting events.[84]

Three Lions

The arms of England are gules, three lions passant guardant or; the earliest surviving record of their use was by Richard I (Richard the Lionheart) in the late 12th century.

Since union with Scotland and Northern Ireland, the arms of England are no longer used on their own; instead they form a part of the conjoined Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom. However, both the Football Association and the England and Wales Cricket Board use logos based on the three lions. In recent years, it has been common to see banners of the arms flown at English football matches, in the same way the Lion Rampant is flown in Scotland.

In 1996, Three Lions was the official song of the England football team for the 1996 European Football Championship, which were held in England.

Rose

The Tudor rose is the national floral emblem of England, and was adopted as a national emblem of England around the time of the Wars of the Roses.[85]

The rose is used in a variety of contexts in its use for England's representation. The Rose of England is a Royal Badge, and is a Tudor, or half-red-half-white rose,[86] symbolising the end of the Wars of the Roses and the subsequent marriage between the House of Lancaster and the House of York. This symbolism is reflected in the Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom and the crest of the FA. However, the rose of England is often displayed as a red rose (which also symbolises Lancashire), such as the badge of the England national rugby union team. A white rose (which also symbolises Yorkshire) is also used on different occasions.

Anthem

England does not have an official designated national anthem, as the United Kingdom as a whole has "God Save the Queen". However, the following are often considered unofficial English national anthems:

"God Save the Queen" is usually played for English sporting events, such as football matches, against teams from outside the UK,[87] although "Land of Hope and Glory" was used as the English anthem for the 2002 Commonwealth Games.[88] Since 2004, "Jerusalem" has been sung before England cricket matches,[89] and "Rule Britannia" (Britannia being the Roman name for Great Britain, a personification of the United Kingdom) was often used in the past for the English national football team when they played against another of the home nations but more recently "God Save the Queen" has been used by the rugby union and football teams.[90]

Gallery

-

Tower of London, London.

-

The Palace of Westminster – the political centre of the United Kingdom.

-

Clifton Suspension Bridge, Bristol.

References

- ^ www.number-10.gov.uk. "Countries within a country". Retrieved 2007-06-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ England -- Britannica Student Encyclopedia. URL retrieved on 6 June 2007.

- ^ National Statistics Online - Population Estimates. URL accessed 6 June 2007.

- ^ The official definition of LUZ (Larger Urban Zone) is used by the European Statistical Agency (Eurostat) when describing conurbations and areas of high population. This definition ranks London highest, above Paris (see Larger Urban Zones (LUZ) in the European Union) ; and a ranking of population within municipal boundaries also puts London on top (see Largest cities of the European Union by population within city limits). However, research by the University of Avignon in France ranks Paris first and London second when including the whole urban area and hinterland, that is the outlying cities as well (see Largest urban areas of the European Union).

- ^ England - Culture. Britain USA. URL accessed September 12, 2006.

- ^ ace.mmu.ac.uk

- ^ BBC NEWS | Country profile: United Kingdom. URL retrieved 6 June 2006.

- ^ "Oxford DNB theme: England, Scotland, and the Acts of Union (1707)" (HTML). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 2007-06-19.

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition

- ^ OED (etymology) entry for Angle)

- ^ Germania by Tacitus. URL accessed November 18, 2006.

- ^ Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum. URL accessed 19 November, 2006.

- ^ OED entry for England

- ^ wiktionary:England

- ^ England expects that every man will do his duty - Nelson

- ^ Bone find may rewrite history, BBC News, June 4, 2002. URL accessed 20 November 2006

- ^ Stephen Oppenheimer, The Origins of the British, Constable and Robinson

- ^ BBC – History – Anglo-Saxons

- ^ Plague – LoveToKnow 1911

- ^ Spread of the Plague

- ^ Cf. "The Reformation must not be confused with the changes introduced into the Church of England during the 'Reformation Parliament' of 1529–36, which were of a political rather than a religious nature, designed to unite the secular and religious sources of authority within a single sovereign power: the Anglican Church did not until later make any substantial change in doctrine". Roger Scruton, A Dictionary Political Thought (Macmillan, 1996), p. 470.

- ^ www.englishindependenceparty.com

- ^ Campaign for an Independent England – Welcome to the Campaign for an Independent England

- ^ BBC politics. URL accessed November 12, 2006.

- ^ BBC talking point. URL accessed November 12, 2006.

- ^ Eurotunnel.com – UK History

- ^ TravelBritain – Kent

- ^ Temperature record changes hands BBC News, September 30, 2003. URL accessed September 12, 2006.

- ^ English Climate Met Office. URL accessed September 12, 2006.

- ^ "Largest EU city". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 2006-10-16.

- ^ Z/Yen Limited (November 2005). "The Competitive Position of London as a Global Financial Centre" (PDF). CityOfLondon.gov.uk. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ^ Financial Centre, by the Corporation of the City of London. URL accessed 20 November, 2006.

- ^ Fact Monster. URL accessed 18 November, 2006.

- ^ Eblex. URL accessed 18 November, 2006.

- ^ The Competitive Position of London as a Global Financial Centre (PDF) (November 2005), City of London government.

- ^ Visit Britain. URL accessed 18 November, 2006.

- ^ Population Estimates National Statistics Online, August 24, 2006. URL accessed September 12, 2006

- ^ Population Estimates National Statistics Online, August 24, 2006. URL accessed September 12, 2006.

- ^ http://www.statistics.gov.uk/cci/nugget.asp?id=760. URL accessed 19 November 2006

- ^ Ancient Britain Had Apartheid-Like Society, Study Suggests

- ^ English and Welsh are races apart

- ^ BBC – "British Immigration Map Revealed" Accessed 16 May, 2007

- ^ BBC Thousands in UK citizenship queue

- ^ 1 in 5 babies in Britain born to immigrants

- ^ Half a million migrants pour into Britain in a year

- ^ National Statistics Online – Immigration over half a million

- ^ Record numbers seek new lives abroad

- ^ Indians largest group among new immigrants to UK

- ^ 1500 immigrants arrive in Britain daily, report says

- ^ 1,500 migrants enter UK a day

- ^ Emigration soars as Britons desert the UK

- ^ 750,000 and rising: how Polish workers have built a home in Britain.

- ^ B.Branston The Lost Gods of England.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica article on Shakespeare. Accessed February 26, 2006.

- ^ MSN Encarta Encyclopedia article on Shakespeare. Accessed February 26, 2006.

- ^ Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia article on Shakespeare. Accessed February 26, 2006.

- ^ RIAA

- ^ Metric system was British - BBC video news

- ^ History of Western Philosophy, Bertrand Russell

- ^ FIFA World rankings

- ^ World Football Elo rankings

- ^ Harris, Rob (2007-11-22). "England fires coach Steve McClaren after failure to qualify for Euro 2008". Associated Press. Retrieved 2007-11-26.

- ^ English: Not America's Language? by Mauro E. Mujica - The Globalist > > Global Culture. URL retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ^ Common law - Tiscali reference. URL retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ^ Yaelf. URL accessed November 15, 2006.

- ^ Whole Earth magazine. URL accessed November 13, 2006.

- ^ British Sign Language (BSL). Sign Community Online, 2006. URL accessed September 12, 2006.

- ^ 2001 Census

- ^ Template:PDFlink. Page 11. European Commission. Retrieved on 7 December 2006

- ^ Jewish Virtual Library – England by Shira Schonenburg. URL retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ^ Manchester Jewish Synagogues, Judaism, Hebrew Congregations and Jewish Organisations in Greater Manchester. URL retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ^ Rabbi Bezalel Rakow – Guardian Unlimited. URL retrieved 6 June 2007.

- ^ BBC. URL accessed 20 November 2006.

- ^ Department for Transport, Transport Trends 2006 (PDF). URL accessed 17 February, 2007.

- ^ Roman Britons after 410 by Martin Henig: British Archaeology Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ^ Anglo-Saxon Origins: The Reality of the Myth by Malcolm Todd. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ^ Legacy of the Vikings By Elaine Treharne, BBC History. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ^ What Did the Normans Do for Us? By Dr John Hudson, BBC History. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ^ The Adventure of the English, Melvyn Bragg, 2003. Pg 21

- ^ "What makes you British?". BBC News online. 2007-03-30.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ St George's events 'not enough'. BBC News, April 23, 2005. URL accessed September 12, 2006.

- ^ "The Great Saint George Revival". BBC News. 23 April 1998. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ St. George – England's Patron Saint

- ^ BBC NEWS | England | Football – shaping a new England?

- ^ National Flowers of the UK, 10 Downing Street. URL accessed September 14, 2006.

- ^ England's Rose – The Official History, Sport Network. Museum of Rugby, June 3, 2005. URL accessed September 18, 2006.

- ^ Guardian – National Anthem faces red card

- ^ "New Statesman – Sport – Jason Cowley loves the Commonwealth Games". Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- ^ "Anthem 4 England - Jerusalem - English Anthems - News". Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- ^ Guardian – National Anthem faces red card

1. ^www.ofsted.gov.uk/

External links

- Template:Wikitravel

- Office for National Statistics

- Enjoy England – The official website of the English Tourist Board

- Enjoy England's Travel Blog – Discover England's best hidden gems

- Official website of the United Kingdom Government

- England-related pages from the BBC

- English Nature – wildlife and the natural world of England.

- English Heritage – national body protecting and promoting English history and heritage.

- Historical and genealogical information from Genuki England