Oxygen

Liquid oxygen (O2 at below −183 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxygen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allotropes | O2, O3 (ozone) and more (see Allotropes of oxygen) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | gas: colorless liquid and solid: pale blue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(O) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abundance | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| in the Earth's crust | 461000 ppm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxygen in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

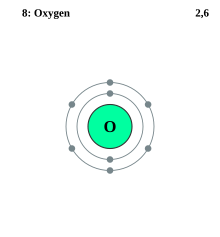

| Atomic number (Z) | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 16 (chalcogens) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [He] 2s2 2p4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | gas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | (O2) 54.36 K (−218.79 °C, −361.82 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | (O2) 90.188 K (−182.962 °C, −297.332 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at STP) | 1.429 g/L | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at b.p.) | 1.141 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Triple point | 54.361 K, 0.1463 kPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 154.581 K, 5.043 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | (O2) 0.444 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | (O2) 6.82 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | (O2) 29.378 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | common: −2 −1,[3] 0, +1,[3] +2[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 3.44 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 66±2 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 152 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | cubic (cP16) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lattice constant | a = 678.28 pm (at t.p.)[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 26.58×10−3 W/(m⋅K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +3449.0×10−6 cm3/mol (293 K)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound | 330 m/s (gas, at 27 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7782-44-7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Michael Sendivogius Carl Wilhelm Scheele (1604, 1771) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

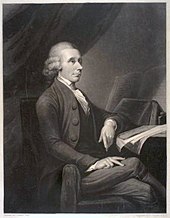

| Named by | Antoine Lavoisier (1777) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of oxygen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Oxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. It is a member of the chalcogen group on the periodic table, and is a highly reactive nonmetallic period 2 element that readily forms compounds (notably oxides) with almost all other elements. At standard temperature and pressure two atoms of the element bind to form dioxygen, a colorless, odorless, tasteless diatomic gas with the formula O

2. Oxygen is the third most abundant element in the universe by mass after hydrogen and helium[6] and the most abundant element by mass in the Earth's crust.[7] Oxygen constitutes 88.8% of the mass of water and 20.9% of the volume of air.[8]

All major classes of structural molecules in living organisms, such as proteins, carbohydrates, and fats, contain oxygen, as do the major inorganic compounds that comprise animal shells, teeth, and bone. Oxygen in the form of O

2 is produced from water by cyanobacteria, algae and plants during photosynthesis and is used in cellular respiration for all complex life. Oxygen is toxic to anaerobic organisms, which were the dominant form of early life on Earth until O

2 began to accumulate in the atmosphere 2.5 billion years ago.[9] Another form (allotrope) of oxygen, ozone (O

3), helps protect the biosphere from ultraviolet radiation with the high-altitude ozone layer, but is a pollutant near the surface where it is a by-product of smog.

Oxygen was independently discovered by Joseph Priestley and Carl Wilhelm Scheele in the 1770s, but Priestley is usually given priority because he published his findings first. The name oxygen was coined in 1777 by Antoine Lavoisier,[10] whose experiments with oxygen helped to discredit the then-popular phlogiston theory of combustion and corrosion. Oxygen is produced industrially by fractional distillation of liquefied air, use of zeolites to remove carbon dioxide and nitrogen from air, electrolysis of water and other means. Uses of oxygen include the production of steel, plastics and textiles; rocket propellant; oxygen therapy; and life support in aircraft, submarines, spaceflight and diving.

Characteristics

Structure

At standard temperature and pressure, oxygen is a colorless, odorless gas with the molecular formula O

2, in which the two oxygen atoms are chemically bonded to each other with a spin triplet electron configuration. This bond has a bond order of two, and is often over-simplified in description as a double bond.[11]

Triplet oxygen is the ground state of the O

2 molecule.[12] The electron configuration of the molecule has two unpaired electrons occupying two degenerate molecular orbitals.[13] These orbitals are classified as antibonding (weakening the bond order from three to two), so the diatomic oxygen bond is weaker than the diatomic nitrogen triple bond in which all bonding molecular orbitals are filled, but some antibonding orbitals are not.[12]

In normal triplet form, O

2 molecules are paramagnetic—they form a magnet in the presence of a magnetic field—because of the spin magnetic moments of the unpaired electrons in the molecule, and the negative exchange energy between neighboring O

2 molecules.[14] Liquid oxygen is attracted to a magnet to a sufficient extent that, in laboratory demonstrations, a bridge of liquid oxygen may be supported against its own weight between the poles of a powerful magnet.[15][16]

Singlet oxygen, a name given to several higher-energy species of molecular O

2 in which all the electron spins are paired, is much more reactive towards common organic molecules. In nature, singlet oxygen is commonly formed from water during photosynthesis, using the energy of sunlight.[17] It is also produced in the troposphere by the photolysis of ozone by light of short wavelength,[18] and by the immune system as a source of active oxygen.[19] Carotenoids in photosynthetic organisms (and possibly also in animals) play a major role in absorbing energy from singlet oxygen and converting it to the unexcited ground state before it can cause harm to tissues.[20]

Allotropes

The common allotrope of elemental oxygen on Earth is called dioxygen, O

2. It has a bond length of 121 pm and a bond energy of 498 kJ·mol-1.[21] This is the form that is used by complex forms of life, such as animals, in cellular respiration (see Biological role) and is the form that is a major part of the Earth's atmosphere (see Occurrence). Other aspects of O

2 are covered in the remainder of this article.

Trioxygen (O

3) is usually known as ozone and is a very reactive allotrope of oxygen that is damaging to lung tissue.[22] Ozone is produced in the upper atmosphere when O

2 combines with atomic oxygen made by the splitting of O

2 by ultraviolet (UV) radiation.[10] Since ozone absorbs strongly in the UV region of the spectrum, it functions as a protective radiation shield for the planet (see ozone layer).[10] Near the earth's surface, however, it is a pollutant formed as a by-product of automobile exhaust.[23]

The metastable molecule tetraoxygen (O

4) was discovered in 2001,[24][25] and was assumed to exist in one of the six phases of solid oxygen. It was proven in 2006 that that phase, created by pressurizing O

2 to 20 GPa, is in fact a rhombohedral O

8 cluster.[26] This cluster has the potential to be a much more powerful oxidizer than either O

2 or O

3 and may therefore be used in rocket fuel.[24][25] A metallic phase was discovered in 1990 when solid oxygen is subjected to a pressure of above 96 GPa[27] and it was shown in 1998 that at very low temperatures, this phase becomes superconducting.[28]

Physical properties

Oxygen is more soluble in water than nitrogen; water contains approximately 1 molecule of O

2 for every 2 molecules of N

2, compared to an atmospheric ratio of approximately 1:4. The solubility of oxygen in water is temperature-dependent, and about twice as much (14.6 mg·L−1) dissolves at 0 °C than at 20 °C (7.6 mg·L−1).[29][30] At 25 °C and 1 atm of air, freshwater contains about 6.04 milliliters (mL) of oxygen per liter, whereas seawater contains about 4.95 mL per liter.[31] At 5 °C the solubility increases to 9.0 mL (50% more than at 25 °C) per liter for water and 7.2 mL (45% more) per liter for sea water.

Oxygen condenses at 90.20 K (−182.95 °C, −297.31 °F), and freezes at 54.36 K (−218.79 °C, −361.82 °F).[32] Both liquid and solid O

2 are clear substances with a light sky-blue color caused by absorption in the red (in contrast with the blue color of the sky, which is due to Rayleigh scattering of blue light). High-purity liquid O

2 is usually obtained by the fractional distillation of liquefied air;[33] Liquid oxygen may also be produced by condensation out of air, using liquid nitrogen as a coolant. It is a highly-reactive substance and must be segregated from combustible materials.[34]

Isotopes and stellar origin

Naturally occurring oxygen is composed of three stable isotopes, 16O, 17O, and 18O, with 16O being the most abundant (99.762% natural abundance).[35] Oxygen isotopes range in mass number from 12 to 28.[35]

Most 16O is synthesized at the end of the helium fusion process in stars but some is made in the neon burning process.[36] 17O is primarily made by the burning of hydrogen into helium during the CNO cycle, making it a common isotope in the hydrogen burning zones of stars.[36] Most 18O is produced when 14N (made abundant from CNO burning) captures a 4He nucleus, making 18O common in the helium-rich zones of stars.[36]

Fourteen radioisotopes have been characterized, the most stable being 15O with a half-life of 122.24 seconds (s) and 14O with a half-life of 70.606 s.[35] All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives that are less than 27 s and the majority of these have half-lives that are less than 83 milliseconds.[35] The most common decay mode of the isotopes lighter than 16O is electron capture to yield nitrogen, and the most common mode for the isotopes heavier than 18O is beta decay to yield fluorine.[35]

Occurrence

Oxygen is the most abundant chemical element, by mass, in our biosphere, air, sea and land.

Oxygen is the third most abundant chemical element in the universe, after hydrogen and helium.[6] About 0.9% of the Sun's mass is oxygen.[8] Oxygen constitutes 49.2% of the Earth's crust by mass[7] and is the major component of the world's oceans (88.8% by mass).[8] It is the second most common component of the Earth's atmosphere, taking up 21.0% of its volume and 23.1% of its mass (some 1015 tonnes).[37][8][38] Earth is unusual among the planets of the Solar System in having such a high concentration of oxygen gas in its atmosphere: Mars (with 0.1% O

2 by volume) and Venus have far lower concentrations. However, the O

2 surrounding these other planets is produced solely by ultraviolet radiation impacting oxygen-containing molecules such as carbon dioxide.

2.

The unusually high concentration of oxygen on Earth is the result of the oxygen cycle. This biogeochemical cycle describes the movement of oxygen within and between its three main reservoirs on Earth: the atmosphere, the biosphere, and the lithosphere. The main driving factor of the oxygen cycle is photosynthesis, which is responsible for modern Earth's atmosphere. Because of the vast amounts of oxygen gas available in the atmosphere, even if all photosynthesis were to cease completely, it would take all the oxygen-consuming processes at the present rate at least another 5,000 years to strip all the O

2 from the atmosphere.[39][40]

Free oxygen also occurs in solution in the world's water bodies. The increased solubility of O

2 at lower temperatures (see Physical properties) has important implications for ocean life, as polar oceans support a much higher density of life due to their higher oxygen content.[41] Polluted water may have reduced amounts of O

2 in it, depleted by decaying algae and other biomaterials (see eutrophication). Scientists assess this aspect of water quality by measuring the water's biochemical oxygen demand, or the amount of O

2 needed to restore it to a normal concentration.[42]

Biological role

Photosynthesis and respiration

In nature, free oxygen is produced by the light-driven splitting of water during oxygenic photosynthesis. Green algae and cyanobacteria in marine environments provide about 70% of the free oxygen produced on earth and the rest is produced by terrestrial plants.[43]

A simplified overall formula for photosynthesis is:[44]

- 6CO

2 + 6H

2O + photons → C

6H

12O

6 + 6O

2 (or simply carbon dioxide + water + sunlight → glucose + dioxygen)

- 6CO

Photolytic oxygen evolution occurs in the thylakoid membranes of photosynthetic organisms and requires the energy of four photons.[45] Many steps are involved, but the result is the formation of a proton gradient across the thylakoid membrane, which is used to synthesize ATP via photophosphorylation.[46] The O

2 remaining after oxidation of the water molecule is released into the atmosphere.[47]

Molecular dioxygen, O

2, is essential for cellular respiration in all aerobic organisms. Oxygen is used in mitochondria to help generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP) during oxidative phosphorylation. The reaction for aerobic respiration is essentially the reverse of photosynthesis and is simplified as:

- C

6H

12O

6 + 6O

2 → 6CO

2 + 6H

2O + 2880 kJ·mol-1

- C

In vertebrates, O

2 is diffused through membranes in the lungs and into red blood cells. Hemoglobin binds O

2, changing its color from bluish red to bright red.[48][22] Other animals use hemocyanin (molluscs and some arthropods) or hemerythrin (spiders and lobsters).[37] A liter of blood can dissolve 200 cc of O

2.[37]

Reactive oxygen species, such as superoxide ion (O2−) and hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2), are dangerous by-products of oxygen use in organisms.[37] Parts of the immune system of higher organisms, however, create peroxide, superoxide, and singlet oxygen to destroy invading microbes. Reactive oxygen species also play an important role in the hypersensitive response of plants against pathogen attack.[46]

An adult human in rest inhales 1.8 to 2.4 grams of oxygen per minute.[49] This amounts to more than 6 billion tonnes of oxygen inhaled by humanity per year. [50]

Build-up in the atmosphere

Free oxygen gas was almost nonexistent in Earth's atmosphere before photosynthetic archaea and bacteria evolved. Free oxygen first appeared in significant quantities during the Paleoproterozoic era (between 2.5 and 1.6 billion years ago). At first, the oxygen combined with dissolved iron in the oceans to form banded iron formations. Free oxygen started to gas out of the oceans 2.7 billion years ago, reaching 10% of its present level around 1.7 billion years ago.[51]

The presence of large amounts of dissolved and free oxygen in the oceans and atmosphere may have driven most of the anaerobic organisms then living to extinction during the oxygen catastrophe about 2.4 billion years ago. However, cellular respiration using O2 enables aerobic organisms to produce much more ATP than anaerobic organisms, helping the former to dominate Earth's biosphere.[52] Photosynthesis and cellular respiration of O

2 allowed for the evolution of eukaryotic cells and ultimately complex multicellular organisms such as plants and animals.

Since the beginning of the Cambrian era 540 million years ago, O

2 levels have fluctuated between 15% and 30% per volume.[53] Towards the end of the Carboniferous era (about 300 million years ago) atmospheric O

2 levels reached a maximum of 35% by volume,[53] allowing insects and amphibians to grow much larger than today's species. Human activities, including the burning of 7 billion tonnes of fossil fuels each year have had very little effect on the amount of free oxygen in the atmosphere.[14] At the current rate of photosynthesis it would take about 2,000 years to regenerate the entire O

2 in the present atmosphere.[54]

History

Early experiments

One of the first known experiments on the relationship between combustion and air was conducted by the second century BCE Greek writer on mechanics, Philo of Byzantium. In his work Pneumatica, Philo observed that inverting a vessel over a burning candle and surrounding the vessel's neck with water resulted in some water rising into the neck.[55] Philo incorrectly surmised that parts of the air in the vessel were converted into the classical element fire and thus were able to escape through pores in the glass. Many centuries later Leonardo da Vinci built on Philo's work by observing that a portion of air is consumed during combustion and respiration.[56]

In the late 17th century, Robert Boyle proved that air is necessary for combustion. English chemist John Mayow refined this work by showing that fire requires only a part of air that he called spiritus nitroaereus or just nitroaereus.[57] In one experiment he found that placing either a mouse or a lit candle in a closed container over water caused the water to rise and replace one-fourteenth of the air's volume before extinguishing the subjects.[58] From this he surmised that nitroaereus is consumed in both respiration and combustion.

Mayow observed that antimony increased in weight when heated, and inferred that the nitroaereus must have combined with it.[57] He also thought that the lungs separate nitroaereus from air and pass it into the blood and that animal heat and muscle movement result from the reaction of nitroaereus with certain substances in the body.[57] Accounts of these and other experiments and ideas were published in 1668 in his work Tractatus duo in the tract "De respiratione".[58]

Phlogiston theory

Robert Hooke, Ole Borch, Mikhail Lomonosov, and Pierre Bayen all produced oxygen in experiments in the 17th century but none of them recognized it as an element.[29] This may have been in part due to the prevalence of the philosophy of combustion and corrosion called the phlogiston theory, which was then the favored explanation of those processes.

Established in 1667 by the German alchemist J. J. Becher, and modified by the chemist Georg Ernst Stahl by 1731,[59] phlogiston theory stated that all combustible materials were made of two parts. One part, called phlogiston, was given off when the substance containing it was burned, while the dephlogisticated part was thought to be its true form, or calx.[56]

Highly combustible materials that leave little residuum, such as wood or coal, were thought to be made mostly of phlogiston; whereas non-combustible substances that corrode, such as iron, contained very little. Air did not play a role in phlogiston theory, nor were any initial quantitative experiments conducted to test the idea; instead, it was based on observations of what happens when something burns, that most common objects appear to become lighter and seem to lose something in the process.[56] The fact that a substance like wood actually gains overall weight in burning was hidden by the buoyancy of the gaseous combustion products. Indeed one of the first clues that the phlogiston theory was incorrect was that metals, too, gain weight in rusting (when they were supposedly losing phlogiston).

Discovery

Oxygen was first discovered by Swedish pharmacist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. He had produced oxygen gas by heating mercuric oxide and various nitrates by about 1772.[56][8] Scheele called the gas 'fire air' because it was the only known supporter of combustion. He wrote an account of this discovery in a manuscript he titled Treatise on Air and Fire, which he sent to his publisher in 1775. However, that document was not published until 1777.[60]

In the meantime, an experiment was conducted by the British clergyman Joseph Priestley on August 1 1774 focused sunlight on mercuric oxide (HgO) inside a glass tube, which liberated a gas he named 'dephlogisticated air'.[8] He noted that candles burned brighter in the gas and that a mouse was more active and lived longer while breathing it. After breathing the gas himself, he wrote: "The feeling of it to my lungs was not sensibly different from that of common air, but I fancied that my breast felt peculiarly light and easy for some time afterwards."[29] Priestley published his findings in 1775 in a paper titled "An Account of Further Discoveries in Air" which was included in the second volume of his book titled Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air.[61][56] Because he had published his findings first, Priestley is usually given priority in the discovery.

The noted French chemist Antoine Laurent Lavoisier later claimed to have discovered the new substance independently. However, Priestley visited Lavoisier in October 1774 and told him about his experiment and how he liberated the new gas. Scheele also posted a letter to Lavoisier on September 30 1774 that described his own discovery of the previously-unknown substance, but Lavoisier never acknowledged receiving it (a copy of the letter was found in Scheele's belongings after his death).[60]

Lavoisier's contribution

What Lavoisier did indisputably do (although this was disputed at the time) was to conduct the first adequate quantitative experiments on oxidation and give the first correct explanation of how combustion works.[8] He used these and similar experiments, all started in 1774, to discredit the phlogiston theory and to prove that the substance discovered by Priestley and Scheele was a chemical element.

In one experiment, Lavoisier observed that there was no overall increase in weight when tin and air were heated in a closed container.[8] He noted that air rushed in when he opened the container, which indicated that part of the trapped air had been consumed. He also noted that the tin had increased in weight and that increase was the same as the weight of the air that rushed back in. This and other experiments on combustion were documented in his book Sur la combustion en général, which was published in 1777.[8] In that work, he proved that air is a mixture of two gases; 'vital air', which is essential to combustion and respiration, and azote (Gk. ἄζωτον "lifeless"), which did not support either.

Lavoisier renamed 'vital air' to oxygène in 1777 from the Greek roots ὀξύς (oxys) (acid, literally "sharp," from the taste of acids) and -γενής (-genēs) (producer, literally begetter), because he mistook oxygen to be a constituent of all acids.[10] Azote later became nitrogen in English, although it has kept the name in French and several other European languages.[8]

Oxygen entered the English language despite opposition by English scientists and the fact that Priestley had priority. This is partly due to a poem praising the gas titled "Oxygen" in the popular book The Botanic Garden (1791) by Erasmus Darwin, grandfather of Charles Darwin.[60]

Later history

John Dalton's original atomic hypothesis assumed that all elements were monoatomic and that the atoms in compounds would normally have the simplest atomic ratios with respect to one another. For example, Dalton assumed that water's formula was HO, giving the atomic mass of oxygen as 8 times that of hydrogen, instead of the modern value of about 16.[62] In 1805, Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and Alexander von Humboldt showed that water is formed of two volumes of hydrogen and one volume of oxygen; and by 1811 Amedeo Avogadro had arrived at the correct interpretation of water's composition, based on what is now called Avogadro's law and the assumption of diatomic elemental molecules.[63][64]

By the late 19th century scientists realized that air could be liquefied, and its components isolated, by compressing and cooling it. Using a cascade method, Swiss chemist and physicist Raoul Pierre Pictet evaporated liquid sulfur dioxide in order to liquefy carbon dioxide, which in turn was evaporated to cool oxygen gas enough to liquefy it. He sent a telegram on December 22 1877 to the French Academy of Sciences in Paris announcing his discovery of liquid oxygen.[65] Just two days later, French physicist Louis Paul Cailletet announced his own method of liquefying molecular oxygen.[65] Only a few drops of the liquid were produced in either case so no meaningful analysis could be conducted.

In 1891 Scottish chemist James Dewar was able to produce enough liquid oxygen to study.[14] The first commercially-viable process for producing liquid oxygen was independently developed in 1895 by German engineer Carl von Linde and British engineer William Hampson. Both men lowered the temperature of air until it liquefied and then distilled the component gases by boiling them off one at a time and capturing them.[66] Later, in 1901, oxyacetylene welding was demonstrated for the first time by burning a mixture of acetylene and compressed O

2. This method of welding and cutting metal later became common.[66]

In 1923 the American scientist Robert H. Goddard became the first person to develop a rocket engine; the engine used gasoline for fuel and liquid oxygen as the oxidizer. Goddard successfully flew a small liquid-fueled rocket 56 m at 97 km/h on March 16 1926 in Auburn, Massachusetts, USA.[66][67]

Industrial production

Two major methods are employed to produce the 100 million tonnes of O

2 extracted from air for industrial uses annually.[60] The most common method is to fractionally-distill liquefied air into its various components, with nitrogen N

2 distilling as a vapor while oxygen O

2 is left as a liquid.[60]

The other major method of producing O

2 gas involves passing a stream of clean, dry air through one bed of a pair of identical zeolite molecular sieves, which absorbs the nitrogen and delivers a gas stream that is 90% to 93% O

2.[60] Simultaneously, nitrogen gas is released from the other nitrogen-saturated zeolite bed, by reducing the chamber operating pressure and diverting part of the oxygen gas from the producer bed through it, in the reverse direction of flow. After a set cycle time the operation of the two beds is interchanged, thereby allowing for a continuous supply of gaseous oxygen to be pumped through a pipeline. This is known as pressure swing adsorption. Oxygen gas is increasingly obtained by these non-cryogenic technologies (see also the related vacuum swing adsorption).[68]

Oxygen gas can also be produced through electrolysis of water into molecular oxygen and hydrogen. A similar method is the electrocatalytic O

2 evolution from oxides and oxoacids. Chemical catalysts can be used as well, such as in chemical oxygen generators or oxygen candles that are used as part of the life-support equipment on submarines, and are still part of standard equipment on commercial airliners in case of depressurization emergencies. Another air separation technology involves forcing air to dissolve through ceramic membranes based on zirconium dioxide by either high pressure or an electric current, to produce nearly pure O

2 gas.[42]

In large quantities, the price of liquid oxygen in 2001 was approximately $0.21/kg.[69] Since the primary cost of production is the energy cost of liquefying the air, the production cost will change as energy cost varies.

For reasons of economy oxygen is often transported in bulk as a liquid in specially-insulated tankers, since one litre of liquefied oxygen is equivalent to 840 liters of gaseous oxygen at atmospheric pressure and 20 °C.[60] Such tankers are used to refill bulk liquid oxygen storage containers, which stand outside hospitals and other institutions with a need for large volumes of pure oxygen gas. Liquid oxygen is passed through heat exchangers, which convert the cryogenic liquid into gas before it enters the building. Oxygen is also stored and shipped in smaller cylinders containing the compressed gas; a form that is useful in certain portable medical applications and oxy-fuel welding and cutting.[60]

Applications

Medical

Uptake of O

2 from the air is the essential purpose of respiration, so oxygen supplementation is used in medicine. Oxygen therapy is used to treat emphysema, pneumonia, some heart disorders, and any disease that impairs the body's ability to take up and use gaseous oxygen.[70] Treatments are flexible enough to be used in hospitals, the patient's home, or increasingly by portable devices. Oxygen tents were once commonly used in oxygen supplementation, but have since been replaced mostly by the use of oxygen masks or nasal cannulas.

Hyperbaric (high-pressure) medicine uses special oxygen chambers to increase the partial pressure of O

2 around the patient and, when needed, the medical staff. Carbon monoxide poisoning, gas gangrene, and decompression sickness (the 'bends') are sometimes treated using these devices. Increased O

2 concentration in the lungs helps to displace carbon monoxide from the heme group of hemoglobin. Oxygen gas is poisonous to the anaerobic bacteria that cause gas gangrene, so increasing its partial pressure helps kill them. Decompression sickness occurs in divers who decompress too quickly after a dive, resulting in bubbles of inert gas, mostly nitrogen and argon, forming in their blood. Increasing the pressure of O

2 as soon as possible is part of the treatment.[70]

Oxygen is also used medically for patients who require mechanical ventilation, often at concentrations above the 21% found in ambient air.

Life support and recreational use

2 is used in space suits

A notable application of O

2 as a low-pressure breathing gas is in modern space suits, which surround their occupant's body with pressurized air. These devices use nearly pure oxygen at about one third normal pressure, resulting in a normal blood partial pressure of O

2.[verification needed] This trade-off of higher oxygen concentration for lower pressure is needed to maintain flexible spacesuits.

Scuba divers and submariners also rely on artificially-delivered O

2, but most often use normal pressure, and/or mixtures of oxygen and air. Pure or nearly pure O

2 use in diving at higher-than-sea-level pressures is usually limited to rebreather, decompression, or emergency treatment use at relatively shallow depths (~ 6 meters depth, or less). Deeper diving requires significant dilution of O

2 with other gases, such as nitrogen or helium, to help prevent oxygen toxicity.

People who climb mountains or fly in non-pressurized fixed-wing aircraft sometimes have supplemental O

2 supplies.[71] Passengers traveling in (pressurized) commercial airplanes have an emergency supply of O

2 automatically supplied to them in case of cabin depressurization. Sudden cabin pressure loss activates chemical oxygen generators above each seat, causing oxygen masks to drop and forcing iron filings into the sodium chlorate inside the canister.[42] A steady stream of oxygen gas is produced by the exothermic reaction. However, even this may pose a danger if inappropriately triggered: a ValuJet airplane crashed after use-date-expired O

2 canisters, which were being shipped in the cargo hold, activated and caused fire. The canisters were mis-labeled as empty, and carried against dangerous goods regulations.[72]

Oxygen, as a supposed mild euphoric, has a history of recreational use in oxygen bars and in sports. Oxygen bars are establishments, found in Japan, California, and Las Vegas, Nevada since the late 1990s that offer higher than normal O

2 exposure for a fee.[73] Professional athletes, especially in American football, also sometimes go off field between plays to wear oxygen masks in order to get a supposed "boost" in performance. However, the reality of a pharmacological effect is doubtful; a placebo or psychological boost being the most plausible explanation.[73] Available studies support a performance boost from enriched O

2 mixtures only if they are breathed during actual aerobic exercise.[74] Other recreational uses include pyrotechnic applications, such as George Goble's five-second ignition of barbecue grills.[75]

Industrial

2 is used to smelt iron into steel.

Smelting of iron ore into steel consumes 55% of commercially-produced oxygen.[42] In this process, O

2 is injected through a high-pressure lance into molten iron, which removes sulfur impurities and excess carbon as the respective oxides, SO2 and CO2. The reactions are exothermic, so the temperature increases to 1700 °C.[42]

Another 25% of commercially-produced oxygen is used by the chemical industry.[42] Ethylene is reacted with O

2 to create ethylene oxide, which, in turn, is converted into ethylene glycol; the primary feeder material used to manufacture a host of products, including antifreeze and polyester polymers (the precursors of many plastics and fabrics).[42]

Most of the remaining 20% of commercially-produced oxygen is used in medical applications, metal cutting and welding, as an oxidizer in rocket fuel, and in water treatment.[42] Oxygen is used in oxyacetylene welding burning acetylene with O

2 to produce a very hot flame. In this process, metal up to 60 cm thick is first heated with a small oxy-acetylene flame and then quickly cut by a large stream of O

2.[76] Rocket propulsion requires a fuel and an oxidizer. Larger rockets use liquid oxygen as their oxidizer, which is mixed and ignited with the fuel for propulsion.

Scientific

Paleoclimatologists measure the ratio of oxygen-18 and oxygen-16 in the shells and skeletons of marine organisms to determine what the climate was like millions of years ago (see oxygen isotope ratio cycle). Seawater molecules that contain the lighter isotope, oxygen-16, evaporate at a slightly faster rate than water molecules containing the 12% heavier oxygen-18; this disparity increases at lower temperatures.[77] During periods of lower global temperatures, snow and rain from that evaporated water tends to be higher in oxygen-16, and the seawater left behind tends to be higher in oxygen-18. Marine organisms then incorporate more oxygen-18 into their skeletons and shells than they would in a warmer climate.[77] Paleoclimatologists also directly measure this ratio in the water molecules of ice core samples that are up to several hundreds of thousands of years old.

Planetary geologists have measured different abundances of oxygen isotopes in samples from the Earth, the Moon, Mars, and meteorites, but were long unable to obtain reference values for the isotope ratios in the Sun, believed to be the same as those of the primordial solar nebula. However, analysis of a silicon wafer exposed to the solar wind in space and returned by the crashed Genesis spacecraft has shown that the Sun has a higher proportion of oxygen-16 than does the Earth. The measurement implies that an unknown process depleted oxygen-16 from the Sun's disk of protoplanetary material prior to the coalescence of dust grains that formed the Earth.[78]

Oxygen presents two spectrophotometric absorption bands peaking at the wavelengths 687 and 760 nm. Some remote sensing scientists have proposed using the measurement of the radiance coming from vegetation canopies in those bands to characterize plant health status from a satellite platform.[79] This approach exploits the fact that in those bands it is possible to discriminate the vegetation's reflectance from its fluorescence, which is much weaker. The measurement is technically difficult owing to the low signal-to-noise ratio and the physical structure of vegetation; but it has been proposed as a possible method of monitoring the carbon cycle from satellites on a global scale.

Compounds

The oxidation state of oxygen is −2 in almost all known compounds of oxygen. The oxidation state −1 is found in a few compounds such as peroxides.[80] Compounds containing oxygen in other oxidation states are very uncommon: −1/2 (superoxides), −1/3 (ozonides), 0 (elemental, hypofluorous acid), +1/2 (dioxygenyl), +1 (dioxygen difluoride), and +2 (oxygen difluoride).

Oxides and other inorganic compounds

Water (H2O) is the oxide of hydrogen and the most familiar oxygen compound. Hydrogen atoms are covalently bonded to oxygen in a water molecule but also have an additional attraction (about 23.3 kJ·mol−1 per hydrogen atom) to an adjacent oxygen atom in a separate molecule.[81] These hydrogen bonds between water molecules hold them approximately 15% closer than what would be expected in a simple liquid with just Van der Waals forces.[82][83]

Due to its electronegativity, oxygen forms chemical bonds with almost all other elements at elevated temperatures to give corresponding oxides. However, some elements readily form oxides at standard conditions for temperature and pressure; the rusting of iron is an example. The surface of metals like aluminium and titanium are oxidized in the presence of air and become coated with a thin film of oxide that passivates the metal and slows further corrosion. Some of the transition metal oxides are found in nature as non-stoichiometric compounds, with a slightly less metal than the chemical formula would show. For example, the natural occurring FeO (wüstite) is actually written as Fe

1−xO, where x is usually around 0.05.[84]

Oxygen as a compound is present in the atmosphere in trace quantities in the form of carbon dioxide (CO

2). The earth's crustal rock is composed in large part of oxides of silicon (silica SiO

2, found in granite and sand), aluminium (aluminium oxide Al

2O

3, in bauxite and corundum), iron (iron(III) oxide Fe

2O

3, in hematite and rust) and other metals.

The rest of the Earth's crust is also made of oxygen compounds, in particular calcium carbonate (in limestone) and silicates (in feldspars). Water-soluble silicates in the form of Na

4SiO

4, Na

2SiO

3, and Na

2Si

2O

5 are used as detergents and adhesives.[85]

Oxygen also acts as a ligand for transition metals, forming metal–O2 bonds with the iridium atom in Vaska's complex,[86] with the platinum in PtF

6,[87] and with the iron center of the heme group of hemoglobin.

Organic compounds and biomolecules

(oxygen is in red, carbon in black and hydrogen in white).

Among the most important classes of organic compounds that contain oxygen are (where "R" is an organic group): alcohols (R-OH); ethers (R-O-R); ketones (R-CO-R); aldehydes (R-CO-H); carboxylic acids (R-COOH); esters (R-COO-R); acid anhydrides (R-CO-O-CO-R); and amides (R-C(O)-NR2). There are many important organic solvents that contain oxygen, including: acetone, methanol, ethanol, isopropanol, furan, THF, diethyl ether, dioxane, ethyl acetate, DMF, DMSO, acetic acid, and formic acid. Acetone ((CH3)2CO) and phenol (C6H5OH) are used as feeder materials in the synthesis of many different substances. Other important organic compounds that contain oxygen are: glycerol, formaldehyde, glutaraldehyde, citric acid, acetic anhydride, and acetamide. Epoxides are ethers in which the oxygen atom is part of a ring of three atoms.

Oxygen reacts spontaneously with many organic compounds at or below room temperature in a process called autoxidation.[88] Most of the organic compounds that contain oxygen are not made by direct action of O

2. Organic compounds important in industry and commerce that are made by direct oxidation of a precursor include ethylene oxide and peracetic acid.[85]

The element is found in almost all biomolecules that are important to (or generated by) life. Only a few common complex biomolecules, such as squalene and the carotenes, contain no oxygen. Of the organic compounds with biological relevance, carbohydrates contain the largest proportion by mass of oxygen. All fats, fatty acids, amino acids, and proteins contain oxygen (due to the presence of carbonyl groups in these acids and their ester residues). Oxygen also occurs in phosphate (PO43−) groups in the biologically important energy-carrying molecules ATP and ADP, in the backbone and the purines (except adenine) and pyrimidines of RNA and DNA, and in bones as calcium phosphate and hydroxylapatite.

Precautions

Toxicity

Oxygen gas (O

2) can be toxic at elevated partial pressures, leading to convulsions and other health problems.[89][90] Oxygen toxicity usually begins to occur at partial pressures more than 50 kilopascals (kPa), or 2.5 times the normal sea-level O

2 partial pressure of about 21 kPa. Therefore, air supplied through oxygen masks in medical applications is typically composed of 30% O

2 by volume (about 30 kPa at standard pressure).[29] At one time, premature babies were placed in incubators containing O

2-rich air, but this practice was discontinued after some babies were blinded by it.[29]

Breathing pure O

2 in space applications, such as in some modern space suits, or in early spacecraft such as Apollo, causes no damage due to the low total pressures used.[91] In the case of spacesuits, the O

2 partial pressure in the breathing gas is, in general, about 30 kPa (1.4 times normal), and the resulting O

2 partial pressure in the astronaut's arterial blood is only marginally more than normal sea-level O

2 partial pressure (see arterial blood gas).

Oxygen toxicity to the lungs and central nervous system can also occur in deep scuba diving and surface supplied diving.[29] Prolonged breathing of an air mixture with an O

2 partial pressure more than 60 kPa can eventually lead to permanent pulmonary fibrosis.[92] Exposure to a O

2 partial pressures greater than 160 kPa may lead to convulsions (normally fatal for divers). Acute oxygen toxicity can occur by breathing an air mixture with 21% O

2 at 66 m or more of depth while the same thing can occur by breathing 100% O

2 at only 6 m.[92][93]

Combustion and other hazards

Highly-concentrated sources of oxygen promote rapid combustion. Fire and explosion hazards exist when concentrated oxidants and fuels are brought into close proximity; however, an ignition event, such as heat or a spark, is needed to trigger combustion.[94] Oxygen itself is not the fuel, but the oxidant. Combustion hazards also apply to compounds of oxygen with a high oxidative potential, such as peroxides, chlorates, nitrates, perchlorates, and dichromates because they can donate oxygen to a fire.

2 at higher than normal pressure and a spark led to a fire and the loss of the Apollo 1 crew.

Concentrated O

2 will allow combustion to proceed rapidly and energetically.[94] Steel pipes and storage vessels used to store and transmit both gaseous and liquid oxygen will act as a fuel; and therefore the design and manufacture of O

2 systems requires special training to ensure that ignition sources are minimized.[94] The fire that killed the Apollo 1 crew on a test launch pad spread so rapidly because the capsule was pressurized with pure O

2 but at slightly more than atmospheric pressure, instead of the ⅓ normal pressure that would be used in a mission.[95][96]

Liquid oxygen spills, if allowed to soak into organic matter, such as wood, petrochemicals, and asphalt can cause these materials to detonate unpredictably on subsequent mechanical impact.[94] On contact with the human body, it can also cause cryogenic burns to the skin and the eyes.

See also

- Oxygen compounds

- Hypoxia, a lack of oxygen

- Hypoxia (environmental) for O

2 depletion in aquatic ecology - Winkler test for dissolved oxygen for instructions on how to determine the amount of O

2 dissolved in fresh water. - Optode for a method of measuring O

2 concentration in solution - Oxygen Catastrophe in geology

- Oxygen isotope ratio cycle

Notes and citations

- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Oxygen". CIAAW. 2009.

- ^ Prohaska, Thomas; Irrgeher, Johanna; Benefield, Jacqueline; Böhlke, John K.; Chesson, Lesley A.; Coplen, Tyler B.; Ding, Tiping; Dunn, Philip J. H.; Gröning, Manfred; Holden, Norman E.; Meijer, Harro A. J. (2022-05-04). "Standard atomic weights of the elements 2021 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-0603. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ a b c Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Arblaster, John W. (2018). Selected Values of the Crystallographic Properties of Elements. Materials Park, Ohio: ASM International. ISBN 978-1-62708-155-9.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ a b Emsley 2001, p.297

- ^ a b "Oxygen". Los Alamos National Laboratory. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Cook & Lauer 1968, p.500

- ^ "NASA Research Indicates Oxygen on Earth 2.5 Billion Years Ago" (Press release). NASA. 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ a b c d Mellor 1939

- ^ "Molecular Orbital Theory". Purdue University. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

- ^ a b Jakubowski, Henry. "Biochemistry Online". Saint John's University. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ An orbital is a concept from quantum mechanics that models an electron as a wave-like particle that has a spacial distribution about an atom or molecule.

- ^ a b c Emsley 2001, p.303

- ^ "Demonstration of a bridge of liquid oxygen supported against its own weight between the poles of a powerful magnet". University of Wisconsin-Madison Chemistry Department DEMONSTRATION LAB. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ^ Oxygen's paramagnetism can be used analytically in paramagnetic oxygen gas analysers that determine the purity of gaseous oxygen. ("Company literature of Oxygen analyzers (triplet)". Servomex. Retrieved 2007-12-15.)

- ^ Krieger-Liszkay 2005, 337-46

- ^ Harrison 1990

- ^ Wentworth 2002

- ^ Hirayama 1994, 149-150

- ^ Chieh, Chung. "Bond Lengths and Energies". University of Waterloo. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- ^ a b Stwertka 1998, p.48

- ^ Stwertka 1998, p.49

- ^ a b Cacace 2001, 4062

- ^ a b Ball, Phillip (2001-09-16). "New form of oxygen found". Nature News. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ^ Lundegaard 2006, 201–04

- ^ Desgreniers 1990, 1117–22

- ^ Shimizu 1998, 767–69

- ^ a b c d e f Emsley 2001, p.299

- ^ "Air solubility in water". The Engineering Toolbox. Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ^ Evans & Claiborne 2006, 88

- ^ Lide 2003, Section 4

- ^ "Overview of Cryogenic Air Separation and Liquefier Systems". Universal Industrial Gases, Inc. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ^ "Liquid Oxygen Material Safety Data Sheet" (PDF). Matheson Tri Gas. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ^ a b c d e "Oxygen Nuclides / Isotopes". EnvironmentalChemistry.com. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- ^ a b c Meyer 2005, 9022

- ^ a b c d Emsley 2001, p.298

- ^ Figures given are for values up to 50 miles (80 km) above the surface

- ^ Walker 1980

- ^ This is calculated by dividing all the free O

2 in the atmosphere to the rate it is used for respiration by the entire biosphere. This is obviously an extreme calculation since most organisms would die well before the pressure of O

2 fell to zero, and therefore the rate of consumption would decrease significantly from the present rate. - ^ From The Chemistry and Fertility of Sea Waters by H.W. Harvey, 1955, citing C.J.J. Fox, "On the coefficients of absorption of atmospheric gases in sea water", Publ. Circ. Cons. Explor. Mer, no. 41, 1907. Harvey however notes that according to later articles in Nature the values appear to be about 3% too high.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Emsley 2001, p.301

- ^ Fenical 1983, "Marine Plants"

- ^ Brown 2003, 958

- ^ Thylakoid membranes are part of chloroplasts in algae and plants while they simply are one of many membrane structures in cyanobacteria. In fact, chloroplasts are thought to have evolved from cyanobacteria that were once symbiotic partners with the progenerators of plants and algae.

- ^ a b Raven 2005, 115–27

- ^ Water oxidation is catalyzed by a manganese-containing enzyme complex known as the oxygen evolving complex (OEC) or water-splitting complex found associated with the lumenal side of thylakoid membranes. Manganese is an important cofactor, and calcium and chloride are also required for the reaction to occur.(Raven 2005)

- ^ CO2 is released from another part of hemoglobin (see Bohr effect)

- ^ "For humans, the normal volume is 6-8 liters per minute." [1]

- ^ (1.8 grams)*(60 minutes)*(24 hours)*(365 days)*(6.6 billion people)/1,000,000=6.24 billion tonnes

- ^ Campbell 2005, 522–23

- ^ Freeman 2005, 214, 586

- ^ a b Berner 1999, 10955–57

- ^ Dole 1965, 5–27

- ^ Jastrow 1936, 171

- ^ a b c d e Cook & Lauer 1968, p.499. Cite error: The named reference "ECE499" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Britannica contributors 1911, "John Mayow"

- ^ a b World of Chemistry contributors 2005, "John Mayow"

- ^ Morris 2003

- ^ a b c d e f g h Emsley 2001, p.300

- ^ Priestley 1775, 384–94

- ^ DeTurck, Dennis (1997). "The Interactive Textbook of PFP96". University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2008-01-28.

{{cite web}}:|chapter=ignored (help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Roscoe 1883, 38

- ^ However, these results were mostly ignored until 1860. Part of this rejection was due to the belief that atoms of one element would have no chemical affinity towards atoms of the same element, and part was due to apparent exceptions to Avogadro's law that were not explained until later in terms of dissociating molecules.

- ^ a b Daintith 1994, p.707

- ^ a b c How Products are Made contributors, "Oxygen"

- ^ "Goddard-1926". NASA. Retrieved 2007-11-18.

- ^ "Non-Cryogenic Air Separation Processes". UIG Inc. 2003. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- ^ Space Shuttle Use of Propellants and Fluids, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 2001=09, retrieved 2007-12-16,

NASAFacts FS-2001-09-015-KSC

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Cook & Lauer 1968, p.510

- ^ The reason is that increasing the proportion of oxygen in the breathing gas at low pressure acts to augment the inspired O

2 partial pressure nearer to that found at sea-level. - ^ "NTSB Summary report". National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved 2007-12-16.)

- ^ a b Bren, Linda (November–December 2002). "Oxygen Bars: Is a Breath of Fresh Air Worth It?". FDA Consumer magazine. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ^ "Ergogenic Aids". Peak Performance Online. Retrieved 2008-01-04.

- ^ "George Goble's extended home page (mirror)".

- ^ Cook & Lauer 1968, p.508

- ^ a b Emsley 2001, p.304

- ^ Hand, Eric (2008-03-13). "The Solar System's first breath". Nature. 452: 259. doi:10.1038/452259a.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Miller et al. 2003

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1997, 28

- ^ Maksyutenko et al. 2006

- ^ Chaplin, Martin (2008-01-04). "Water Hydrogen Bonding". Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ Also, since oxygen has a higher electronegativity than hydrogen, the charge difference makes it a polar molecule. The interactions between the different dipoles of each molecule cause a net attraction force.

- ^ Smart 2005, 214

- ^ a b Cook & Lauer 1968, p.507

- ^ Crabtree 2001, 152

- ^ Cook & Lauer 1968, p.505

- ^ Cook & Lauer 1968, p.506

- ^ Since O

2's partial pressure is the fraction of O

2 times the total pressure, elevated partial pressures can occur either from high O

2 fraction in breathing gas or from high breathing gas pressure, or a combination of both. - ^ Cook & Lauer 1968, p.511

- ^ Wade, Mark (2007). "Space Suits". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- ^ a b Wilmshurst, Peter (1998). "ABC of oxygen: Diving and oxygen". British Medical Journal. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- ^ Donald 1992

- ^ a b c d Werley 1991

- ^ No single ignition source of the fire was conclusively identified, although some evidence points to arc from an electrical spark). (Report of Apollo 204 Review Board NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA History Office, NASA HQ, Washington, DC)

- ^ Chiles 2001

References

- Agostini, D. (1995). "Positron emission tomography with oxygen-15 of stunned myocardium caused by coronary artery vasospasm after recovery". British Heart Journal. 73 (1): 69–72. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Berner, Robert A. (1999-09-18). "Atmospheric oxygen over Phanerozoic time". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA (20): 10955–57. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|wolume=ignored (help) - Britannica contributors (1911). "John Mayow". Encyclopaedia Britannica (11th edition ed.). Retrieved 2007-12-16.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help);|edition=has extra text (help) - Brown, Theodore L. (2003). Chemistry: The Central Science. Prentice Hall/Pearson Education. p. 958. ISBN 0130484504.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Cacace, Fulvio (2001). "Experimental Detection of Tetraoxygen". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 40 (21): 4062–65. doi:10.1002/1521-3773(20011105)40:21%3c4062::AID-ANIE4062%3e3.0.CO;2-X.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Campbell, Neil A. (2005). Biology, 7th Edition. San Francisco: Pearson - Benjamin Cummings. pp. 522–23. ISBN 0-8053-7171-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Chiles, James R. (2001). Inviting Disaster: Lessons from the edge of Technology: An inside look at catastrophes and why they happen. New York: HarperCollins Publishers Inc. ISBN 0-06-662082-1.

- Cook, Gerhard A. (1968). "Oxygen". In Clifford A. Hampel (ed.). The Encyclopedia of the Chemical Elements. New York: Reinhold Book Corporation. pp. 499–512. LCCN 68-29938.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Crabtree, R. (2001). The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals (3rd edition ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 152. ISBN 978-0471184232.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Daintith, John (1994). Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists. CRC Press. ISBN 0750302879.

- Desgreniers, S (1990). "Optical response of very high density solid oxygen to 132 GPa". J. Phys. Chem. 94: 1117–22.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Dole, Malcolm (1965). "The Natural History of Oxygen" (PDF). The Journal of General Physiology. 49: 5–27. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- Donald, Kenneth (1992). Oxygen and the Diver. ISBN 1854211765.

- Emsley, John (2001). "Oxygen". Nature's Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 297–304. ISBN 0198503407.

- Evans, David Hudson (2006). The Physiology of Fishes. CRC Press. p. 88. ISBN 0849320224.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Fenical, William (1983). "Marine Plants: A Unique and Unexplored Resource". Plants: the potentials for extracting protein, medicines, and other useful chemicals (workshop proceedings). DIANE Publishing. p. 147. ISBN 1428923977.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Freeman, Scott (2005). Biological Science, 2nd Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson - Prentice Hall. pp. 214, 586. ISBN 0-13-140941-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- Harrison, Roy M. (1990). Pollution: Causes, Effects & Control (2nd Edition ed.). Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 0-85186-283-7.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Hirayama, Osamu (1994-02-). "Singlet oxygen quenching ability of naturally occurring carotenoids". Lipids. 29 (2). Springer Berlin / Heidelberg: 149–50. doi:10.1007/BF02537155. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - How Products are Made contributors (2002). "Oxygen". How Products are Made. The Gale Group, Inc. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Jastrow, Joseph (1936). Story of Human Error. Ayer Publishing. p. 171. ISBN 0836905687. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- Krieger-Liszkay*, Anja (2005). "Singlet oxygen production in photosynthesis". Journal of Experimental Botanics. 56. Oxford Journals: 337–46. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|published=ignored (help) - Lide, David R. (2003). "Section 4, Properties of the Elements and Inorganic Compounds; Melting, boiling, and critical temperatures of the elements". CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (84th Edition ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Lundegaard, Lars F. "Observation of an O8 molecular lattice in the phase of solid oxygen". Nature. 443: 201–04. doi:10.1038/nature05174. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|publishdate=ignored (help) - Maksyutenko, P. (2006). "A direct measurement of the dissociation energy of water". J. Chem. Phys.: 125. doi:181101.

{{cite journal}}: Check|doi=value (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Meyer, B.S. (September 19–21, 2005). "Nucleosynthesis and Galactic Chemical Evolution of the Isotopes of Oxygen" (PDF). Proceedings of the NASA Cosmochemistry Program and the Lunar and Planetary Institute. Workgroup on Oxygen in the Earliest Solar System. Gatlinburg, Tennessee. 9022. Retrieved 2007-01-22.

{{cite conference}}: External link in|conferenceurl=|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|conferenceurl=ignored (|conference-url=suggested) (help) - Miller, J.R.; Berger, M.; Alonso, L.; Cerovic, Z.; Goulas, Y.; Jacquemoud, S.; Louis, J.; Mohammed, G.; Moya, I.; Pedros, R.; Moreno, J.F.; Verhoef, W.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. "Progress on the development of an integrated canopy fluorescence model". Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 2003. IGARSS '03. Proceedings. 2003 IEEE International. Retrieved 2008-01-22.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Morris, Richard (2003). The last sorcerers: The path from alchemy to the periodic table. Washington, D.C.: Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 0309089050.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - Parks, G. D. (1939). Mellor's Modern Inorganic Chemistry (6th edition ed.). London: Longmans, Green and Co.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Priestley, Joseph (1775). "An Account of Further Discoveries in Air". Philosophical Transactions. 65: 384–94. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

- Raven, Peter H. (2005). Biology of Plants, 7th Edition. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company Publishers. pp. 115–27. ISBN 0-7167-1007-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Roscoe, Henry Enfield (1883). A Treatise on Chemistry. D. Appleton and Co. p. 38.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Shimizu, K. (1998). "Superconductivity in oxygen". Nature. 393: 767–69.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Smart, Lesley E. (2005). Solid State Chemistry: An Introduction (3 ed.). CRC Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0748775163.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Stwertka, Albert (1998). Guide to the Elements (Revised Edition ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508083-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Walker, J. (1980). "The oxygen cycle". In Hutzinger O. (ed.). Handbook of Environmental Chemistry. Volume 1. Part A: The natural environment and the biogeochemical cycles. Berlin; Heidelberg; New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 258. ISBN 0387096884.

- Wentworth Jr., Paul (2002-12-13). "Evidence for Antibody-Catalyzed Ozone Formation in Bacterial Killing and Inflammation". Science. 298 (5601): 2195–219. doi:10.1126/science.1077642.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Werley, Barry L. (Edtr.) (1991). "Fire Hazards in Oxygen Systems". ASTM Technical Professional training. Philadelphia: ASTM International Subcommittee G-4.05.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - World of Chemistry contributors (2005). "John Mayow". World of Chemistry. Thomson Gale. Retrieved 2007-12-16.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)

External links

- Los Alamos National Laboratory – Oxygen

- WebElements.com – Oxygen

- Oxygen (O2) Properties, Uses, Applications

- Oxidizing Agents > Oxygen

- Roald Hoffmann article on "The Story of O"