Korean Buddhist sculpture

Korean Buddhist sculpture is one of the major areas of Korean art. Buddhism, a religion originating in what is now India, was transmitted to Korea via China in the late fourth century.[1] The religion inspired the production of temple architecture and devotional art. The Buddhist sculpture of Korea is indebted to prototypes developed in India, Central Asia, and China. However, from these influences, a distinctive Korean style formed.[2][3] Korean Buddhas typically exhibit Korean facial characteristics, were made with different casting and carving techniques, and employed only some of the motifs that were developed earlier in Buddhist art. [4] Additionally, Korean artisans fused together different styles from different regions with their own tastes to form a native art tradition.[5] These Korean stylistic developments were greatly influential in the Asuka, Hakuho, and Tenpyo periods of Japanese Buddhist sculpture when Korea transmitted Buddhism to Japan in the sixth century.[6][7][8] Some of the finest and most technically accomplished Buddhist sculpture in East Asia were produced in Korea.[9] Buddhist sculpture remains an important form of art in Korea today.

Background

Each individual Buddhist sculpture has various characteristics and attributes which art historians use as clues to determine when and where it was made. Sometimes a statue will have an inscription or contain a document which attests to when, where, and who made it. Sometimes, there are reliable archaeological records which state where a statue was excavated. However, when neither of these sources of information are available, scholars can still glean important information on an individual statue by its style, the particular iconography employed by the artist, and physical characteristics, such as the material used to make the statue, the percentage of metals used in an alloy, casting and carving techniques, and various other contextual clues.

Many Buddhist sculptures in Korea have not survived the vagaries of time and invasion. Those that have are typically small bronze votive images for private worship or sculpture carved in granite, the most abundant material available in Korea. Monumental sculpture for state-sponsored monasteries and devotional objects for royalty, for the most part, have not survived. Although wood and lacquer images were also created in Korea, the earliest wood sculpture that is still extant, not counting the Koryu-ji Maitreya, is a Goryeo true-image of a Buddhist monk from the early 10th century and classified as Treasure no. 999. Gilt-bronze was a common material used for sculpture. However, because bronze was an expensive metal artisans begin using other materials. In Unified Silla, casters began using iron. Of further note is the abundance of granite on the Korean peninsula with many images carved from the living rock.

Three Kingdoms period (traditional 57 BCE–668)

Fourth and fifth centuries

According to the Samguk sagi and Samguk yusa, the two oldest extant histories of Korea, Buddhism was officially introduced to Korea during the fourth century. In addition, the Haedong goseungjeon states that monks from China were already in Korea prior to its official reception. Sundo, a monk from Former Qin, a northern Chinese state, was received by Goguryeo in 372 and a Serindian monk, Malananda, from southern China's Eastern Jin Dynasty was received by Paekche in 384.[10] Archaeological discoveries have corroborated these assertions of the early introduction of Buddhism into Korea with the discovery of Goguryeo tomb murals with Buddhist motifs and the excavation of lotus shaped roof tiles dated to the fourth century.[11][12] The rulers of both Korean kingdoms welcomed the foreign monks and immediately ordered monasteries be built for their use. The construction of Buddhist images soon followed.

-

Detail of Buddha, Goguryeo Korea, late 5th century. Mural painting, eastern ceiling of main burial chamber, Jangcheon-ri Tomb No.1, Jian, Jilin province, China.

-

Detail of Bodhisattvas, Goguryeo Korea, late 5th century. Mural painting, eastern ceiling of main burial chamber, Jangcheon-ri Tomb No.1, Jian, Jilin province, China.

The Ttukseom (Ttuksôm) Buddha (image), named for the area of Seoul in which it was discovered, is the earliest statue of Buddha in Korea.[13] Scholars date it to the late fourth or early fifth century, around 400.[14] The five centimeter tall gilt-bronze statuette follows certain stylistic conventions originating in Ghandara (present-day Pakistan), and which were later adopted by China.[15] These include the rectangular platform upon which the Buddha sits which depicts two lions, a common symbol of Buddha. Additionally, it displays the dhyana mudra, a gesture of meditation commonly found in early seated Buddhas of China and Korea. The stylistic similarities of this Buddha to those found in China lead most scholars to conclude that the image is an import.[16] Two Chinese examples, one at the Asian Art Museum (image) and the other, shown below, at the National Palace Museum in Taipei (image) illustrate the similarities. However, the possibility remains that the image is a Korean copy of a Chinese prototype.[17]

The discovery of the Ttukseom Buddha near a known Baekje settlement, fortress, and first capital suggests the figure may be an example of Baekje sculpture. A very similar meditating Buddha discovered in the later Baekje capital of Sabi (now known as Buyeo) supports this theory.[18] Other scholars suggest that the figure may be a Goguryeo piece because of the close stylistic similarities the figure has with the northern dynastic art, a typical feature of early Goguryeo sculpture.[19]

-

A Chinese prototype of the Ttukseom Buddha at the National Palace Museum in Taipei, Taiwan.

The only other known examples of Korean Buddhist sculpture from the fourth or fifth century are some terra cotta fragments from Goguryeo.

Sixth century

Goguryeo

One of the oldest surviving Korean Buddhas discovered so far is the Yŏn'ga (Revised Romanization: Yeon-ga) Buddha. The Buddha, the only one of a thousand commissioned that has survived, gets its name from the inscription on its back that mentions a previously unknown Goguryeo reign period. While it was discovered in Uiryong in Gyeongsangnam-do, former Silla territory, the inscription clearly states the statue was cast in Nangnang (present-day Pyongyang), Goguryeo. The statue is valuable because it has a clear date of manufacture, 539, and its provenance. Additionally, it proves that images from Goguryeo were sent to Silla.

The rather crude carvings on the mandorla of the Buddha exhibits motion and dynamism typical of Goguryeo art. The figure also exhibits the abahya (no fear) mudra in its upraised proper right hand while the proper left hand displays the verada (wish-granting) mudra. Both mudras are typical of early Korean standing Buddhist sculpture and the folding of the last two fingers of the proper left hand to the palm is a uniquely Korean style. The Yon'ga Buddha also displays other attributes common to early Goguryeo Buddhas including the lean face, prominent protuberances on the head (Sanskrit: ushnisa), large hands disproportionate to the body, an emphasis on the front of the figures, fishtail flaring of the robes on the sides, and the flame imagery on the halo.[20][21]

The prototype of this Buddha derives from the non-Chinese Tuoba clan of the Xianbei people who established the Northern Wei dynasty in northern geographic China. An example of a Northern Wei prototype, dated to 524, can be found at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, shown below. An Eastern Wei Buddha (image), dated to 536, is at the University of Pennsylvania Museum. Both images show the strong influence of the Northern Wei and its derivative dynasties.

-

Yŏn'ga Buddha, Goguryeo, 539. Gilt bronze, h. 16.3 cm. National Museum of Korea, National Treasure no. 119.

-

Back view of the Yŏn'ga Buddha.

-

Altarpiece dedicated to Buddha Maitreya, Northern Wei dynasty (386–534), dated 524 Zhengding xian, Hebei province, China Gilt bronze; H. 30 1/4 in. (76.9 cm); W. 16 in. (40.6 cm); D. 9 3/4 in. (24.8 cm). Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The stiffness of early Goguryeo sculpture is sometimes attributed to the harsh climate of the kingdom which was situated in northern Korea and Manchuria.[22] The replacement of the typically elongated and lean face of Goguryeo sculpture, exemplified by the Yŏn'ga Buddha and the Standing Bodhisattva with triple head ornament shown below, with images with plump faces and gently depicted robes, exemplified by the Wono-ri Bodhisattva, may reflect the conquering of the Han River valley from Baekje in 475 [23] or the introduction of gentler climes. These changes probably reflect, directly or indirectly, the influence of Baekje style[24] or from Goguryeo diplomatic contacts with the southern Chinese dynasties.

The provenance of the standing Bodhisattva with triple head ornament is unknown. Based on common stylistic similarities, such as the fishtail draperies, the large hands, and the two incised lines on the chest indicating an undergarment (a southern Chinese convention) with the Yon'ga Buddha, most scholars believe that it is originally from Goguryeo. The Bodhisattva is only modeled in the front, another Northern Wei characteristic, and the unfinished back has several pegs. These pegs have led some scholars to believe that this Bodhisattva was once a central figure in a single-mandorla triad.

-

Standing Bodhisattva with triple head ornament, probably Goguryeo, mid-6th c. Gilt bronze, h. 15 cm. National Museum of Korea, Treasure No. 333.

-

Wono-ri Bodhisattva, Goguryeo, first half of the 6th c. Ceramic, h. 17 cm. National Museum of Korea.

A seated Buddha at the National Museum of Korea is starkly different from its chronological counterpart, the Kunsu-ri seated Buddha from Baekje. The Buddha displays typical Goguryeo traits, such as the rounded usnisa and head and hands disproportion ally large to the body.[25] The image displays the dhyana mudra. The depiction of the folds of the robe over a now lost rectangular throne is exuberant with no sense of following a set scheme.[26]

Baekje

Baekje sculpture of the 6th century reflect the influence of the native and foreign regimes ruling China during the period of Northern and Southern Dynasties. While Korean and Chinese records show direct diplomatic contacts between Baekje and the Northern Wei dynasty occurred during this time period, they pale in comparison to the numerous diplomatic missions between Baekje and the southern dynasties of China. Further complicating the understanding of the source of inspiration for Baekje Buddhist sculpture is the fact that the southern dynasties were influential in the development of northern sculpture and the fact that few images from the southern regimes have survived.

One of the most frequent types of images that were made throughout the century are single-mandorla triads. The similarities between the triads found in the former Baekje and Goguryeo kingdoms suggests that the introduction of such images came from both Goguryeo itself as well as China. An example of the influence of the Northern Wei style is the statue now at the National Museum of Korea. This image, probably once a part of a single-mandorla triad, has robes draped in the same style as the Yong’a Buddha. However, the Baekje-specific modifications, such as the gentleness of the face, Omega-like folds in the under robe, and a sense of stability exhibited in the expansiveness of the robes as they flare out clearly differentiate this image from those from Goguryeo.

Another example of sixth century sculpture is a triad now at the Gyeongju National Museum. Like contemporaneous examples from Goguryeo, the statue exhibits traits typical of the Northern Wei style, especially in the depiction of the robes. Some similarities with Goguryeo-specific traits include the fairly crude depiction of the flames in the mandorla, simplification being a common trait in extant early sculpture. The roundness of the face, the smile of the central Buddha as well as the harmonious proportions, static nature of the image, and a sense of warmth and humanity are features typically associated with the Southern Dynasties of China, and frequently occur in features of Baekje sculpture as well.[27] The warm climate and fertile environment the kingdom was situated along with native sensibilities are credited as reasons for the Baekje style.[28]

A Baekje soapstone seated Buddha discovered at the Kunsu-ri temple site in Buyeo displays the soft roundness and static nature of the early Baekje style during the second half of the sixth century.[29] Unlike the Ttukseom seated Buddha, the Kunsu-ri Buddha features the robes of the Buddha draped over the rectangular platform and does away with the lions common in earlier images. The symmetrically stylized drapery folds is followed in later Japanese images, such as the Shakyamuni Triad in Hōryū-ji. Like the Ttukseom Buddha, the Kunsu-ri Buddha follows early Chinese and Korean conventions displaying the dhyana mudra. This particular mudra is notably absent in subsequent Japanese Buddhist sculpture which perhaps indicates that the iconography was out of style in Korea by the time Buddhist sculpture began arriving in Japan in the mid-sixth century.[30][31] The seated Buddhas of the late sixth century begin to do away with the meditation gesture in favor of the wish-granting gesture and protection gesture. An example of this kind of seated Buddha is the Paekche triad now at the Tokyo National Museum and is followed by subsequent Japanese images, such as the aforementioned Shakyamuni Triad (image) in Hōryū-ji.

A standing Bodhisattva (image) now at the Buyeo National Museum was excavated from Kunsu-ri (Gunsu-ri) along with the seated Buddha. The influence of Southern Liang art is particularly obvious in this image especially because an analogous image survives in China. The standing Kunsu-ri Bodhisattva also exhibits attributes very different from its contemperaneous Eastern Wei prototypes, such as an emphasis on the headgear and broad face and different iconographic styles employed. The smile of the image is a typical example of the famous Baekje smile commonly found on images from Baekje in both the sixth and seventh century.

-

Pensive Bodhisattva Maitreya, Baekje, late 6th century. Gilt bronze, H. 5.5 cm; L.: 5.5

Korean influence in early Japanese sculpture

The Baekje kingdom's style was particularly influential in the initial stages of Asuka sculpture. It was in 552 that King Seong of Baekje sent a gilt bronze image of Sakyumuni to Yamato Japan according to the Nihon Shoki. Most scholars, based on other Japanese records, consider a 538 date to be more accurate.[32] While it is impossible to know what this first Buddha in Japan looked like, an image similar to the Yong'a Buddha, contemperaneous because it is dated to 539, leads some scholars to speculate that King Seong’s proselytizing image looked similar to it. Another Japanese source, the Gangoji engi, however, identifies the image as the "prince." This suggests that the initial image was the prince Sidhartha in the pensive pose on the verge of enlightenment, an iconography popular in China. Images in the pensive pose are almost always associated with Maitreya in Korea. However, another iconography associated with the prince Sidhartha is the Buddha at birth. Since this source also lists items for a lustration ceremony some scholars believe that the image was of the infant Buddha. Although Buddhism was introduced into Yamato Japan at a relatively early period, it was not until the seventh century that the pro-Buddhist Soga clan succeeded in eliminating its rivals to allow Buddhism enjoy the support of the central polity.

A passage in the Nihon Shoki states that in 577 King Wideok of Baekje sent to the Yamato polity another Buddhist image, a temple architect, and a maker of images. The passage clearly indicates that the Japanese still needed Korean artisans skilled in metal casting techniques and knowledgeable about specific iconography to construct images. In 584, a stone statue of Maitreya and another image simply identified as a Buddha by the Nihon Shoki were sent as part of a diplomatic exchange and are the last official, royally commissioned Baekje images recorded to be sent to Japan in the sixth century. Such exchanges, both official and unofficial, were integral in establishing early Japanese Buddhist sculpture.

Many extant Baekje sculpture survive in Japan today. Horyu-ji Treasure no. 151 (image) is accepted by virtually all Japanese authorities to be of Korean origin [33] and was brought to Japan in the middle sixth century.[34] The four rectangular cavities in the back of the statue is a trait far more common in Korean than Japanese sculpture.[35] The image was probably used as a private devotional icon brought by Korean settlers. Hōryū-ji Treasure no. 158 (image), a pensive image is another image generally considered by Japanese scholars to be from Korea and is dated on stylistic grounds to the mid-sixth century.[36][37] The Funagatayamajinja Bodhisattva, probably once part of a triad, has a crown with three flowers which was common early Three Kingdoms sculpture but not extant in Asuka sculpture. The image is believed to have originated in Korea.[38]

Hōryū-ji Treasure no. 196 (image) is a mandorla for a triad that was made in Korea and can be arguably dated to the late sixth century, 594.[39] The triad’s inscription contains phrases very similar to two Paekche pieces, a Puyo triad (image) and a mandorla once part of a triad dated to 596 (image ). This mandorla incorporates the typical features found in older Korean-style triads, including the odd number of Buddhas of the Past, the floral scroll inside the inner halo, and the jewel found at the apex of the head halo.

Silla

Buddhism was officially accepted by the Silla court only in 527 or 528 although the religion was known to its people earlier due to the efforts of monks from Goguryeo in the fifth century.[40][41] The late acceptance of the religion is often attributed to the geographic isolation of the kingdom, the lack of easy access to China, and the conservatism of the court. However, once Buddhism was accepted by the court, it received wholesale state sponsorship. One example of lavish state support is Hwangnyongsa, a temple which housed an approximately five meter tall Buddha.[42] The statue was revered as one of the kingdom's three great treasures and was destroyed by the Mongols after surviving for 600 years. Excavations have revealed several small pieces of the Buddha and huge foundation stones remain to testify to the great size of the statue.[43]

Seventh century

Goguryeo

Unfortunately, no Goguryeo sculpture from the 7th century has survived or has yet been discovered. Two pieces that have been attributed to the Korean and Mohe Balhae state may actually be from Goguryeo.

Baekje

Several Baekje images from the seventh century survive today. An important image is the Sosan Triad.

A pensive image (image) at the National Museum of Tokyo is probably from Baekje.

-

Buddhist Monk. Three Kingdoms of Korea period, Baekje. 6th c., circa 600. Gilt bronze, h. 10.2 cm. Asian Art Museum, San Francisco. Gift of Namkoong Ryun.

-

Semi-seated Bodhisattva Maitreya, Baekje, mid-7th c. Gilt bronze. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

-

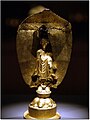

Rare gilt-bronze bodhisattva from the Baekje kingdom, 7th century.

Baekje images in Japan

It is possible that Korean sculptors crafted the Buddha at Asuka-dera in the late sixth or seventh century.[44]

The Kanshoin pensive bodhisattva (image) has three traits that suggest it was an import from Korea or made by a Korean immigrant in Japan.[45] The strong constriction of the upper body, the incised line chiseled into the eyebrow, and tassel on the front of the crown.[46] Scholars currently debate whether Hōryū-ji Dedicated treasure no. 156 (image) is Korean in origin or made in Japan, influenced by Korean styles. An inscription on its base can be plausibly attributed to either a 606 or 666 date. An early date would suggest a Korean origin because of the still developing nature of Japanese sculpture at the time. By 666, plenty of indigenous Japanese sculpture can be found. Some Korean traits include the emaciated body, three-tiered crown and head knot, and the extreme stylization of the drapery over the base. Either way, the image is an important example of Korean traits in early Japanese art.

A single-mandorla triad, Hōryū-ji Dedicated Treasure no. 143 (image), now in the possession of the Tokyo National Museum is a particularly fine example of Baekje sculpture in Japan from the sixth or seventh century.[47] The Korean origins of the statue are based on the round and warm faces typical of Baekje style, the absence of an air of solemnity and austerity typical of the Tori style, the casting technique which used nails instead of spacers, and the intaglio effect on the bronze the artisan used to make the eyebrows, a typical Korean technique.

The Dainichibo standing Buddha, Sekiyamajinja Bodhisattva, Hōryū-ji Treasure no. 165 may all be from Korea as well.[48]

Other possible examples of Baekje sculpture in Japan are the hidden image at Zenkoji (image)[49], the Kudara Kannon (literally Baekje Avalokiteshvara) at Hōryū-ji, and the Yumedono Kannon.

-

Asukadera Big Buddha.

-

Standing Buddha and attendants, Baekje, 6th–7th c. Gilt bronze. Tokyo National Museum, Dedicated Horyu-ji Treasure no. 143.

-

Kudara Kannon

-

Kudara Kannon

-

Pensive Bodhisattva Maitreya. Hakuho period or possibly Three Kingdoms of Korea period, 7th c. Gilt bronze, h. with pedestal 31 cm. Tokyo National Museum.

Silla

Sillan figures continue to show the influence of Northern Qi style in the seventh century. This can be seen in the tall columnar Buddha and a child-like Buddha which has many similarities to recently discovered Buddha sculptures from Longxingsi, Shandong in China. The child-like Buddha shows typical Sillan sculptural traits that are often found in stone work, namely the large head and youthful, innocent air of the Buddha. Additionally, the iconographic details of the statue, not found in Chinese sculpture, suggests that Silla had direct contact with artists from southern India and Sri Lanka. Ancient records also support this suggestion because several foreign monks were said to have resided in Hwangnyongsa translating Buddhist sutras and texts. Pensive figures also continued to be popular.

-

Yangp'yong Buddha, Silla, second half of the 6th c. or first half of the 7th c. Gilt bronze, h. 30cm. National Museum of Korea, National Treasure no. 186.

-

Standing Bhaisajyaguru, Silla, first half of 7th c. Gilt bronze, h. 31 cm. National Museum of Korea.

-

Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva, Silla, 6th c. Gilt bronze, h. 20 cm. National Museum of Korea, National Treasure no. 127.

Pensive images

The pensive pose involves a figure that has one leg crossed over a pendant leg, the ankle of the crossed leg rests on the knee of the pendant leg. The elbow of the figure's raised arm rests on the crossed leg's knee while the fingers rest or almost rest on the cheek of the head bent in introspection.

In Ghandara during the Kushan period, the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, was depicted in a princely pose called variously the pensive posture, seated pendant, or semi-seated in contemplation. This pose was adapted by northern Chinese dynasties. An example from Northern Qi is shown below. The adoption of the pensive pose to the iconography of the Maitreya, the future Buddha, seems to have originated in Korea because it does not occur in India, Central Asia, or China.[50]

In Korea, the technically difficult pensive posture was adapted by all three kingdoms and transformed into a particularly Korean style.[51] While in China the pensive iconography was typically a subordinate image in a triad or was often small in size. In Korea, particularly exemplified by examples from Silla, the pensive Maitreya became a central figure of worship with several heroic-sized figures surviving. Pensive images were popular in the other two kingdoms. In early Baekje pensive statues have a characteristic parabolic drapery, a fragment of such a statue (image) is held at the Buyeo National Museum, and this style can be found in Baekje images now in Japan. A pensive image said to have been excavated in Pyongyang, now at the Ho-am Art Museum, is the only surviving example from Goguryeo and is evidence that stylistic elements were transmitted to Silla.[52] Nevertheless, most surviving pensive images are from Silla.

The cult of Maitreya was particularly influential in sixth and seventh centuries of the Three Kingdoms period. Sillan kings styled themselves as rulers of a Buddha land, the King symbolizing the Buddha. This religious adaptation is also exemplified in the Hwarang corp, a group of aristocratic youth who were groomed for leadership in the endless wars on the peninsula. The leader of the Hwarang was believed to be the incarnation of Maitreya, a uniquely Korean adaptation of the religion.[53] Maitreya, it was believed, would ascend to earth as the future Buddha in 56 million years and this believe was incorporated into Silla's desire to unite the peninsula. Japanese records also suggest that Sillan images given to the Sillan Hata Clan are the current Koryo-ji Miroku Bosatsu and the Naki Miroku.[54]. The Koryu-ji Miroku, dated to 620-640, is stylistically a Korean image, is made from red pine which is indigenous to Korea, and the carving technique of carving inward from a single log is a Korean technique.[55][56] The Korean cult of Maitreya, and the major influence of Korean-style pensive images on Japan in the Asuka period.[57] Korean influence on Japanese Buddhist art was very strong during 552-710.[58]

Two of the most famous pensive Maitreyas are National Treasure no. 78 and National Treasure no. 83. Both figures were said to have been found in Silla territory and are dated to the late sixth or early seventh century. They were probably commissioned by the royal family. National Treasure no. 78 shows the influence of Northern and Eastern Wei styles. Although the style employed is archaic, X-ray studies of the statue, suggests that it is the younger of the two because of the sophistication of the casting, the bronze being no thicker than one centimeter, the rarity of air bubbles, and the high quality metal.[59]

-

Northern Qi. National Museum of Korea.

-

Semi-seated Bodhisattva Maitreya, Silla, 6th c. Gilt bronze, h. 28.5 cm. National Museum of Korea, Treasure no. 331.

-

Semi-seated Bodhisattva Maitreya, second half of the 6th c. Gilt bronze, h. 83.2 cm. National Treasure no. 78. National Museum of Korea, National Treasure no. 78.

National Treasure no. 83, exhibiting stylistic influence from Northern Qi, for a time, was believed to be from Baekje. However, recent research strongly suggests, based on numerous pieces of evidence, suggests that the statue was produced in Silla and scholarly consensus seems to agree on that point. A similar stone pensive statue found in Silla territory and a head with a similar crown excavated at Hwangnyongsa indicates a Silla origin. National Treasure no. 83 is also important because it illustrates the close connection between Korea and Japan during this period. Koryu-ji's almost identical[60] Miroku Bosatsu (Maitreya Bodhisattva) (image), a national treasure of Japan, is now believed to be of Silla manufacture because of the use of red pine, a wood used for Korean sculpture, ancient Japanese records, and the use of Korean carving techniques.

-

Side view of a Semi-seated Bodhisattva Maitreya, Silla, late 6th or early 7th c. Gilt bronze, h. 93.5 cm. National Treasure no. 83. National Museum of Korea, National Treasure no. 83.

Later pensive images from Silla.

-

Semi-seated Bodhisattva Maitreya, Silla, first half of 7th c. Gilt bronze, h. 27.5 cm. National Museum of Korea.

-

Semi-seated Bodhisattva Maitreya, Silla, early 7th c. Gilt bronze, h. 17.1 cm. National Museum of Korea.

A later pensive image, now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a particularly fine example of Baekje sculpture. A chronologically contemporaneous figure from seventh century Japan shows the influence of the Baekje style specifically in the handling of the torso, the triple upright crown, and the locks of hair falling over the shoulder. Another Baekje pensive image: (image).

-

Semi-seated Bodhisattva Maitreya, Baekje, mid-7th c. Gilt bronze. Metropolitan Museum of Art.\

-

Semi-seated Bodhisattva Maitreya, Asuka Japan, 7th c. Gilt bronze. Tokyo National Museum.

Unified Silla (668–935)

The Silla Kingdom, backed by the powerful Tang Empire, defeated the Baekje Kingdom in 660 and the Koguryo Kingdom in 668 and ended centuries of internecine warfare in Korea. King Munmu then defeated and drove out the Tang armies successfully unifying most of Korea under the Unified Silla dynasty. The unification of the three kingdoms is reflected in some early Unified Silla sculptures.

After a period of estrangement with Tang China, diplomatic relations resumed and the so-called international style of the Tang heavily influenced Korea as it did much of the rest of Asia.[61] [62] Buddhism was heavily sponsored and promoted by the royal court. The early century of the Unified Silla period is known as a golden age of Korean history where the kingdom enjoyed the peace and stability to produce fabulous works of art. The central Buddha of the Seokguram Grotto, a UNESCO World Heritage site, is recognized as one of the finest examples of Buddhist sculpture in eastern Asia.[63]

However, the political instability and weakened monarchy of the late eighth century seems to have had an effect on artisans as Buddhist sculpture began to become formulaic and lose vitality in the use of line and form. [64][65] During the later days of Unified Silla, iron was substituted as a cheaper alternative to bronze and was used to cast many Buddhas and one can see regional characteristics creeping into the style of sculptures as local warlords and strongmen began to break away from the orbit of the royal family in Kumseong (now modern-day Gyeongju).

After the destruction of the Baekje Kingdom, elements of Baekje style and early styles.

-

Stone Buddhist stele at the Gongju National Museum in South Korea. Although dated to the beginning of the Unified Silla period, stylistic evidence and the inscription show that strong elements of Baekje influence are evident.

-

National Museum of Korea.

-

Standing Bodhisattva Maitreya (left), 719. Granite, h. 1.83 m. National Museum of Korea, National Treasure no. 81. Standing Amitabha (right), 719. Granite, h. 1.74 m. National Museum of Korea, National Treasure no. 82.

-

National Museum of Korea.

-

Seated Vairocana, 9th c. Stone. National Museum of Korea.

-

Seated Vairocana, late 9th century. Iron, h. 112 cm. National Museum of Korea.

-

Standing Vairocana, 9th c. Gilt bronze; 52.8 cm. Tokyo National Museum, Ogura Collection.

-

Standing Bhaisajyaguru, middle 8th c. 1.77 m. Gyeongju National Museum, National Treasure no. 28.

-

Standing Bhaisajyaguru, 9th c. Gilt bronze, h. 29.2 cm. National Museum of Korea.

A strong Tang Chinese influence affected Unified Silla art. The Korean Buddhist sculpture of this period can be identified by the "undeniable sensuality" of the "round faces and dreamy expressions" and "fleshy and curvaceous bodies" of extant figures. [3].

-

Standing Buddha. Unified Silla period, 7th c., circa 700. Gilt bronze, h. 47.3 cm. Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, Avery Brundage Collection.

-

Standing Buddha, gilt-bronze, Unified Silla. Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, South Korea.

-

Seated Buddha, early 10th c. Cast iron, h. 150 cm. National Museum of Korea.

Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392)

The Goryeo Dynasty succeeded Unified Silla as ruler of the Korean peninsula. Like their predecessors, the Goryeo court lavishly sponsored Buddhism and Buddhist arts. The early phase of Goryeo art is characterized by the waning but influential effect of Unified Silla prototypes, the discarding of High Tang style, and the incorporation of regionally distinctive styles which reflected the influence of local aristocrats who had grown powerful during the declining days of Unified Silla and also reflects the fact that the capital was moved from southeastern Korea to Kaegyong (now modern-day Kaesong).

The bronze life-size image of King Taejo, the founder of the Goryeo Dynasty is technically not a Buddhist sculpture. However, the similarities of the statue to earlier bronze images of the Buddha, such as the elongated ears, a physical attribute of the Buddha, is suggestive of the relationship the royalty had with the religion.

One example of the lingering influence of Unified Silla art is the Seated Sakyamuni Buddha at the National Museum of Korea which can be dated to the tenth century.[66] This statue is stylistically indebted to the central figure at Seokguram and some scholars suggest that the statue is from the Great Silla period. Both Buddhas employ the same "earth-touching" mudra which was first popularized in Korea by the Seokguram image. The fan-shaped folding of cloth between the legs of the Buddha, the way the clothing on the image was depicted, and the "cross-legged seated posture" are all typical of Unified Silla sculpture.[67] The Buddha is the largest iron Buddha surviving in Korea. It was cast in multiple pieces and today one can see the different seams where the statue was pieced together. In the past the statue would have been covered in lacquer or gilt to hide the joints. Interestingly, the bottom of the nose, the ends of the ears, and the hands are reproductions and not part of the original statue.

The Eunjin Mireuk is example of early Goryeo sculpture demonstrating the rise of regional styles and the abandoning of a strict interpretation of the standard iconography of Buddhist images.[68] The statue is believed to be a representation of the Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva, the Bodhisattva of Mercy, although it is popularly known as Maitreya. The statue is over 18 meters tall and took over 30 years to complete.[69][70] The statue is valuable because it demonstrates developments unique to Chungcheong-do and Gyeonggi-do.[71] Additionally, some scholars posit that these huge stones may have once been originally for Shamanistic practices and later subsumed into a Buddhist image.

Few reliably dated Buddhist sculptures from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries have survived and so "it is difficult to assess the production of sculpture related to" the rising popularity of Seon Buddhism (Ch. Chan, Jp. Zen) and its association with the ruling military family of the mid-Goryeo period.[72]

The seated Avalokiteshvara in "royal ease" pose from the 14th century at the National Museum of Korea shows the stylistic influence of Tibetan Lamaist Buddhism which was favored by the Yuan Mongol court.[73] However, some scholars have suggested this statue is an import.

Early Goryeo (918–1170)

-

Statue of King Taejo, 10th c. Bronze, 143.5 cm. North Korea.

-

Seated Sakyamuni Buddha, 10th c. Cast iron, 2.88 m. National Museum of Korea, Treasure no. 332.

-

Seated Buddha.

-

Seated Buddha, early 10th c. Cast iron, h. 132 cm. National Museum of Korea.

-

Eunjin Mireuk, 931–968. Stone, h. 18.12 m.

-

Head of Buddha, 10th–11th c. Cast iron, h. 37.4 cm. National Museum of Korea.

-

Maitreya, early Goryeo period. Hyang'un-gak.

-

Seated bodhisattva, early Goryeo period. Woljeong-sa.

Middle Goryeo (1170–1270

Late Goryeo (1270–1392)

-

Seated Avalokiteshvara, 14th century. Gilt bronze, h. 38.5 cm. National Museum of Korea.

-

Seated Buddha, late Goryeo. Guimet Museum.

Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910)

The dynastic change from the Goryeo to the Joseon was a relatively peaceful one. However, for the first time since Buddhism was accepted by the courts of the Three Kingdoms, the religion fell out of favor with the king and his court. The decadent royal patronage by the Goryeo kings and the growing power of the temples and clergy led the Joseon kings to suppress the religion in favor of Neo-Confucianism. While some kings were Buddhists in their private life, the government funds for temples and the commissioning and quality of statues declined.

Like most Korean works of art, early Joseon sculpture fared poorly in the Japanese invasions of Korea from 1592-1598 and few survive today. The Japanese invasion is the dividing line between early Joseon and late Joseon. The bravery of the many monks who fought against the Japanese invaders was recognized after the war. While never the official religion of the court, Buddhism enjoyed a resurgence and many of the temples and statues that are seen in Koreatoday were built from the seventeenth century onward.

Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910)

-

National Museum of Korea.

-

Vairocana Buddha (middle figure), 1628. Gilt bronze, h. 12.6 cm. Monk (left), 1628. Giltbronze, h. 9.7 cm. National Museum of Korea.

Modern

Modern

-

Standing Buddha, 20th century. Gilt bronze, h. 33 m. Beopjusa.

-

Seated Buddha, 20th century. Bronze. Seoraksan.

-

Yakcheonsa, Jeju-do.

Notes

- ^ Arts of Korea | Explore & Learn | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Korea And The Korean People

- ^ Best, "Yumedono", 13

- ^ Arts of Korea | Explore & Learn | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Korean Buddhist Sculpture (5th–9th century) | Thematic Essay | Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Arts of Korea | Explore & Learn | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Template:Ja icon Standing Buddha

- ^ http://eng.buddhapia.com/_Service/_ContentView/ETC_CONTENT_2.ASP?pk=0000593748&sub_pk=&clss_cd=0002169717&top_menu_cd=0000000592&menu_cd=0000008845&menu_code=&image_folder=color_11&bg_color=2B5137&line_color=3A6A4A&menu_type=

- ^ Arts of Korea | Explore & Learn | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Kim, Won-Yong, pg. 71

- ^ Kim, Won-Yong, pg. 71

- ^ Lena Kim

- ^ Kim, Won-Yong, pg. 71

- ^ Kim, Won-Yong, pg. 71

- ^ Pak and Whitfield, pg. 42

- ^ Kim, Won-Yong, pg. 71

- ^ Korea, 1–500 A.D. | Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Pak and Whitfield, pg. 66

- ^ Pak and Whitfield, pg. 42

- ^ Korean Buddhist Sculpture (5th–9th century) | Thematic Essay | Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Korean Sculpture (Ancient, Koguryo Period, Paekche Period, Paekche Period, Shilla Period, Unified Shilla Period, Metalwork, Pottery, Wood Crafts, Handicrafts)

- ^ Korean Sculpture (Ancient, Koguryo Period, Paekche Period, Paekche Period, Shilla Period, Unified Shilla Period, Metalwork, Pottery, Wood Crafts, Handicrafts)

- ^ Korea, 1–500 A.D. | Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Korean Sculpture (Ancient, Koguryo Period, Paekche Period, Paekche Period, Shilla Period, Unified Shilla Period, Metalwork, Pottery, Wood Crafts, Handicrafts)

- ^ Pak and Whitfield, pg. 82

- ^ Pak and Whitfield, pg. 82

- ^ Korean Buddhist Sculpture (5th–9th century) | Thematic Essay | Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Korean Sculpture (Ancient, Koguryo Period, Paekche Period, Paekche Period, Shilla Period, Unified Shilla Period, Metalwork, Pottery, Wood Crafts, Handicrafts)

- ^ Divinity, pg. 194

- ^ Divinity, pg. 194

- ^ Pak and Whitfield, pg. 82

- ^ McCallum, pg. 151–152

- ^ McCallum, pg. 150

- ^ McCallum states that Kuno Takeshi described this statue had a "stupid-looking face" or "vacant-looking face".

- ^ McCallum, pg. 157

- ^ McCallum, pg. 158

- ^ McCallum, pg. 159: Professor Junghee Lee has expressed reservations about whether this image is actually from Korea.

- ^ McCallum, pg. 173, 175

- ^ McCallum, pg. 176, 178

- ^ Korean Sculpture (Ancient, Koguryo Period, Paekche Period, Paekche Period, Shilla Period, Unified Shilla Period, Metalwork, Pottery, Wood Crafts, Handicrafts)

- ^ Korea, 500–1000 A.D. | Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Korean Sculpture (Ancient, Koguryo Period, Paekche Period, Paekche Period, Shilla Period, Unified Shilla Period, Metalwork, Pottery, Wood Crafts, Handicrafts)

- ^ Korean Sculpture (Ancient, Koguryo Period, Paekche Period, Paekche Period, Shilla Period, Unified Shilla Period, Metalwork, Pottery, Wood Crafts, Handicrafts)

- ^ http://eng.buddhapia.com/_Service/_ContentView/ETC_CONTENT_2.ASP?pk=0000593748&sub_pk=&clss_cd=0002169717&top_menu_cd=0000000592&menu_cd=0000008845&menu_code=&image_folder=color_11&bg_color=2B5137&line_color=3A6A4A&menu_type=

- ^ McCallum, pg 175

- ^ McCallum, pg 175-176

- ^ Nara National Museum

- ^ McCallum, pg 176

- ^ The exact copy of Ikkou Sanzon Amida Nyorai, the sacred Amida Golden Triad at Zenkouji, Nagano

- ^ Junghee Lee, pg. 344 and 353

- ^ Pensive Bodhisattva [Korea] (2003.222) | Works of Art | Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Pak and Whitfield, pg. 110

- ^ Junghee Lee, pg. 345

- ^ Junghee Lee, pg. 346

- ^ Junghee Lee, pg. 347

- ^ The Korean origin of the Koryu-ji Miroku is now accepted by Kuno Takeshi, Inoue Tadashi, Uehara Soichi, and Christine Gunth. Junghee Lee, pg. 347

- ^ Junghee Lee, pg. 348

- ^ Junghee Lee, pg. 353

- ^ Pak and Whitfield, pg. 124

- ^ Pak and Whitfield, pg. 112

- ^ Asian Art in the Birmingham Museum of Art by Donald A. Wood

- ^ [1]

- ^ http://whc.unesco.org/archive/advisory_body_evaluation/736.pdf

- ^ http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/06/eak/ht06eak.htm]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Korea And The Korean People

- ^ Korea And The Korean People

- ^ Kim, Lena pg. 286

- ^ ::: Cultural Heritage, the source for Koreans' Strength and Dream :::

- ^ Kim, Lena, pg. 286

- ^ ::: Cultural Heritage, the source for Koreans' Strength and Dream :::

- ^ Kim, Lena, pg. 286

- ^ Kim, Lena, pg. 287–288

References

- "AsianInfo.org: Korean Scultpure". Retrieved 2007-03-08.

- Best, Jonathan W. (1990). "Early Korea's Role in the Stylistic Formulation of the Yumedono Kannon, a Major Monument of Seventh-Century Japanese Buddhist Sculpture". Korea Journal. 30 (10): 13–26..

- Best, Jonathan W. (1998), "King Mu and the Making and Meanings of Miruksa", in Buswell, Robert E. (ed.), Religions of Korea in Practice, Princeton University Press (published 2007), ISBN 0-691-11347-5.

- Best, Jonathan W. (2003), "The Transmission and Transformation of Early Buddhist Culture in Korea and Japan", in Richard, Naomi Noble (ed.), Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan, Japan Society, ISBN 0-913304-54-9.

- Chin, Hong-sup (1964). "Simplicity and Grandeur: Sculpture of Koryo Dynasty". Korea Journal. 4 (10): 21–25..

- "Fukuoka Art Museum: Standing Buddha". Retrieved 2007-03-08.

- Grayson, James Huntley (2002). Korea: A Religious History. UK: Routledge. ISBN 070071605X.

- Hammer, Elizabeth; Smith, ed., Judith G. (2001), The Arts of Korea: A Resource for Educators, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0-58839-009-8

{{citation}}:|last2=has generic name (help); Check|isbn=value: checksum (help). - Hiromitsu, Washizuka; Park, Youngbok; Kang, Woo-bang; Richard, Naomi Noble (2003), Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan, New York: Japan Society, ISBN 0-913304-54-9.

- Hollenweger, Richard R., ed. (1999), The Buddhist Architecture of the Three Kingdoms Period in Korea, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne.

- Kim, Lena. "Buddhist Sculpture". Indiana University: East Asian Studies Center. Retrieved 2007-03-08.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - Kim, Lena (2003), "Early Korean Buddhist Sculptures and Related Japanese Examples: Iconographic and Stylistic Comparisons", in Richard, Naomi Noble (ed.), Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan, Japan Society, ISBN 0-913304-54-9.

- Kim, Lena (1998), "Tradition and Transformation in Korean Buddhist Sculpture", in Smith, Judith G. (ed.), Arts of Korea, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0-87099-850-1.

- Kim, Won-yong (1960). "An Early Gilt-bronze Seated Buddha from Seoul". Artibus Asiae. 23 (1): 67–71..

- Kuno, Takeshi, ed. (1963), A Guide to Japanese Sculpture, Tokyo: Mayuyama & Co.

- Kwak, Dong-seok (2003), "Korean Gilt-Bronze Single Mandorla Buddha Triads and the Dissemination of East Asian Sculptural Style", in Richard, Naomi Noble (ed.), Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan, Japan Society, ISBN 0-913304-54-9.

- Lee, Junghee (2003), "Goryeo Buddhist Sculpture", in Kim, Kumja Paik (ed.), Goryeo Dynasty: Korea's Age of Enlightenment, 918–1392, Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, ISBN 0-939117-25-8.

- Lee, Junghee (1993). "The Origins and Development of the Pensive Bodhisattva Images of Asia". Artibus Asiae. 53 (3/4): 311–353..

- Lee, Soyoung. "Korean Buddhist Sculpture (5th–9th century A.D.)". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2007-03-08.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - McCallum, Donald F. (March 1982). "Korean Influence on Early Japanese Buddhist Sculpture". Korean Culture. 3 (1): 22–29.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: year (link). - McCallum, Donald F. (2001). "The Earliest Buddhist Statues in Japan". Artibus Asiae. 61 (2): 149–188..

- Paik Kim, Kumja, ed. (2003), Goryeo Dynasty: Korea's Age of Enlightenment, 918–1392, San Francisco: Asian Art Museum, ISBN 0-939117-25-8.

- Pak, Youngsook; Whitfield, Roderick (2002), Handbook of Korean Art: Buddhist Sculpture, Seoul: Yekyong, ISBN 89-7084-192-X

- Rowan, Diana Pyle (1969). "The Yakushi Image and the Shaka Trinity of the Kondo, Horyuji: A Study of Drapery Problems". Artibus Asiae. 31 (4): 241–275..

- Saburosuke, Tanabe (2003), "From the Stone Buddhas of Longxingsi to Buddhist Images of Three Kingdoms Korea and Asuka-Hakuho Japan", in Richard, Naomi Noble (ed.), Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan, Japan Society, ISBN 0-913304-54-9.

- Sadao, Tsuneko S.; Wada, Stephanie (2003), Discovering the Arts of Japan: A Historical Overview, Tokyo: Kondansha International, ISBN 4-7700-2939-X

- Shuya, Onishi (2003), "The Monastery Koruyji's "Crowned Maitreya" and the Stone Pensive Bodhisattva Excavated at Longxingsi", in Richard, Naomi Noble (ed.), Transmitting the Forms of Divinity: Early Buddhist Art from Korea and Japan, Japan Society, ISBN 0-913304-54-9.

- Smith, Judith G., ed. (1998), Arts of Korea, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 0-87099-850-1.

- Soper, Alexander C. (1951). "Notes on Horyuji and the Sculpture of the Suiko Period". The Art Bulletin. 33 (2): 77–94..

- "The British Museum: Japanese Buddhist Sculpture". Retrieved 2007-03-11.

- "The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Buddhist Sculpture". Retrieved 2007-03-11.