White-winged fairywren

| White-winged Fairy-wren | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male in breeding plumage, Coolmunda Dam, Queensland | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | M. leucopterus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Malurus leucopterus Dumont, 1824

| |

The White-winged Fairy-wren (Malurus leucopterus) is a species of passerine bird in the Maluridae family. It is endemic to the dryer parts of central Australia, stretching from central Queensland and South Australia across to Western Australia, and is part of the large order of passerines. Like other fairy-wrens, it exhibits marked sexual dimorphism with one or more males of a social group adopting brightly coloured plumage during the breeding season. The female is sandy-brown with light blue tail feathers and is smaller than the male. The male in breeding plumage has a bright blue body, black bill, and white wings. However, younger but sexually mature males are almost indistinguishable from females and make up a large proportion of the breeding males each year. As a result, a troop of White-winged Fairy-wrens is typically observed as a group of small, inconspicuous brown birds accompanied by one blue older male in the spring and summer months. Three subspecies are recognised, with one occurring on Dirk Hartog Island and another on Barrow Island off the coast of Western Australia. Males of these island forms have black rather than blue plumage in breeding season.

The White-winged Fairy-wren, which mainly eats insects, is found in heathland and arid scrubland, where low shrubs provide cover. Like other fairy-wrens, it is a cooperative breeding species, with small groups of birds maintaining and defending territories year-round. Groups consist of a socially monogamous pair with several helper birds who assist in raising the young. These helpers are progeny that have attained sexual maturity yet remain with the family group for one or more years after fledging. Although not yet confirmed genetically, the White-winged Fairy-wren may be sexually promiscuous, meaning that although they form pairs between one male and one female, each partner will mate with other individuals and even assist in raising the young from such pairings. As part of a courtship display, male wrens pluck petals from flowers and display them to females.

Taxonomy

The White-winged Fairy-wren was first collected by French naturalists Jean René Constant Quoy and Joseph Paul Gaimard in September 1818, on Louis de Freycinet's voyage around the Southern Hemisphere. A subsequent shipwreck resulted in the loss of the specimen, but a painting entitled Mérion leucoptère by Jacques Arago survived and led to the bird's description in 1824 by French ornithologist Charles Dumont de Sainte-Croix;[2][3] its specific epithet derived from the Ancient Greek leuko- 'white' and pteron 'wing'.[4]

Ironically, the original specimen was of the black-plumaged subspecies from Dirk Hartog Island, which was not recorded again for 80 years. Meanwhile, the widespread blue-plumaged subspecies had been discovered and described as two seperate species by John Gould in 1865.[3] He called one that had been collected from inland New South Wales the White-winged Superb Warbler, M. cyanotus, while another specimen, which appeared to have a white back and wings, was described as M. leuconotus, the White-backed Superb Warbler. It was not until the early 20th century that both forms were considered to be the one species,[5] with Mack in 1934 considering the specific name leuconotus as taking precedence,[6] and more recent studies following suit.[7] The back region between the shoulders is in fact bare, with feathers arising from the shoulder (scapular) region and sweeping inwards in differing patterns; this had confused early naturalists into describing two species.[8]

It is a member of the Maluridae family and is one of 12 species in its genus, Malurus. It is most closely related to the Australian Red-backed Fairy-wren, with which it makes up a phylogenetic clade sister to the White-shouldered Fairy-wren of New Guinea.[9] Termed the bicoloured wrens by Schodde, these three species are notable for their lack of head patterns and ear tufts, as well as their one-coloured black or blue plumage with contrasting shoulder or wing colour; they replace each other across northern Australia and New Guinea.[10]

The White-winged Fairy-wren was originally named the Blue-and-white Wren, and early observers, such as Norman Favaloro of Victoria, refer to them by this name.[11] However, like other fairy-wrens, the White-winged Fairy-wren is unrelated to the true wren (family Troglodytidae). It was previously classified as a member of the old world flycatcher family Muscicapidae[12][13] and later as a member of the warbler family Sylviidae[14] before being placed in the newly recognised Maluridae in 1975.[15] More recently, DNA analysis has shown the Maluridae family to be related to the Meliphagidae (honeyeaters), the Pardalotidae (pardalotes, scrubwrens, thornbills, gerygones and allies), and the Petroicidae (Australian robins) in the large superfamily Meliphagoidea.[16][17]

Subspecies

There are, at present, three recognised subspecies of Malurus leucopterus. Both black-plumaged forms have been called Black-and-white Fairy-wren.

- M. l. leuconotus is endemic to mainland Australia and distinct in that it is the only subspecies to have nuptial males showing prominent blue-and-white plumage.[18] The specific epithet is derived from the Ancient Greek leukos 'white' and notos 'back'.[4] Birds in the southern parts of its range tend to be smaller than those in the north.[19]

- M.l. leucopterus is restricted to Dirk Hartog Island, off the western coast of Australia, and nuptial males display black-and-white plumage.[18] This subspecies is the smallest of the three and bears a proportionally longer tail.[19] It was collected again in 1916 by Tom Carter, 98 years after de Freycinet's expedition collected the type specimen.[20]

- M.l. edouardi, like M.l. leucopterus, have black-and-white coloured males, and are found only on Barrow Island, also off the western coast of Australia.[18] Birds of this subspecies are larger than those of M. l. leucopterus but have a shorter tail. The female has a more cinnamon tinge to its plumage than the grey-brown of the other two subspecies.[19] It was described by A.J. Campbell in 1901.[21]

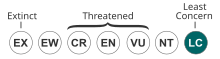

M.l. leucopterus and M.l. edouardi are both generally smaller than their mainland relatives, and both subspecies tend to have smaller family groups consisting of only one male and one female, with an occasional helper bird.[22] While the island species and mainland species have been found to have similar social structure, breeding pairs on both islands have, on average, smaller clutches, longer incubation times, and fewer living fledglings.[22] Additionally, while M.l. leuconotus is considered of least concern by the IUCN due to its widespread occurrence, both island subspecies are considered vulnerable by the Australian government due to their delicate nesting sites that are easily disturbed by human construction and habitation.[1]

Evolutionary History

Both island subspecies are closer in distance to mainland populations of leuconotus than to each other; Dirk Hartog is 2 km (1¼ mi) from the mainland while Barrow Island is 56 km (35 mi) from the mainland. The three populations last intermingled at the beginning of the present interglacial period, some 8,000 to 10,000 years ago, at a time when sea levels were lower and both islands connected with the mainland.[18] As a result, both subspecies have long been thought to be more closely related to the mainland subspecies than they are to each other, and a 2002 study of mitochondrial DNA has supported this.[23] At present, there are three possible situations from which the three races of White-winged Fairy-wren could have evolved. The first suggests that black-and-white plumage is an ancestral condition and following separation of the three populations, blue-and-white plumage evolved in the mainland species.[18] The second hypothesis suggests that black-and-white plumage evolved convergently on the two separate islands.[18] The third suggests that black-and-white plumage evolved once from the blue-and-white ancestral condition, and later the mainland species re-evolved blue plumage.[23]

Description

Measuring 11–13.5 cm (4⅓–5⅓ in) in length, White-winged Fairy-wrens are one of the two smallest species of Malurus.[24] Males typically weigh between 7.2 g (0.25 oz) and 10.9 g (0.38 oz) while females weigh between 6.8 g (0.24 oz) and 11 g (0.39 oz).[7] Averaging 8.5 mm (0.3 in) in males and 8.4 mm (0.3 in) in females,[7] the bill is relatively long, narrow and pointed and wider at the base.[25] Wider than it is deep, the bill is similar in shape to those of other birds that feed by probing for or picking insects off their environs.[26]

Fully matured adults are sexually dimorphic, as the male is larger and differs in colour from the female. The adult female is sandy-brown with a very light blue tail, while the nuptially plumed male has a black bill, white wings and shoulders, and a wholly cobalt blue or black body (depending on subspecies).[24] These contrasting white feathers are especially highlighted in flying and ground displays in breeding season.[27] Males in eclipse plumage resemble females though may be distinguished by their darker bills.[28] Both sexes have long, slender, distinct tails at an upward angle from their bodies.[3] Measuring around 6.25 cm (2½ in), the tail feathers have a white fringe, which disappears with wear.[29]

Nestlings, fledglings, and juveniles exhibit brown plumage and pink-brown bills and their tails are shorter than those of adults. Immature males develop blue tail feathers and darker bills by late summer or autumn (following a spring or summer breeding season), while young females develop light blue tails. By the subsequent spring, all males are fertile and have developed cloacal protuberances, which store sperm. In contrast, during the breeding season, fertile females develop oedematous brood patches, bare areas on their bellies.[24] Males entering their second or third year may develop spotty blue and white plumage during the breeding season. By their fourth year, males have assumed their nuptial plumage, where the scapulars, secondary wing coverts, and secondary flight feathers are white while the rest of their bodies are a vibrant cobalt blue. All sexually mature males molt twice a year, before the breeding season in winter or spring, and afterwards in autumn; rarely, a male may moult directly from nuptial to nuptial plumage.[28] Breeding males' blue plumage, particularly the ear-coverts, is highly iridescent due to the flattened and twisted surface of the barbules.[30] The blue plumage also reflects ultraviolet light strongly, and so may be even more prominent to other fairy-wrens, whose colour vision extends into this part of the spectrum.[31]

Vocalisations

In 1980, Tideman characterised five different patterns of calls among Malurus leucopterus leuconotus; these were recognised by Pruett and Jones among the island subspecies l. edouardi. The main call is a reel made by both sexes in order to establish territory and unify the group. It is a long song of “rising and falling notes” that is first signaled by 3–5 chip notes. Although seemingly weak in sound, the reel carries a long way above the stunted shrubland. A harsh trit call is often used to establish contact (especially between mothers and their young) and to raise alarm; it is characterised by a series of “loud and abrupt” calls that vary in frequency and intensity. Adults will use a high-pitched peep that may be made intermittently with reels as a contact call to birds that are more distant. nestlings, Fledglings, and females around the nest will use high pips—quiet, high-pitched, and short calls. When used by a mature female, they are mixed with harsh calls. Nestlings may also make “Gurgling” noises when they are being fed. The subordinate helpers and feeders may make this sound as well.[32][33]

Distribution and Habitat

The White-winged Fairy-wren is particularly well adapted to dry environments, and M.l. leuconotus is found throughout arid and semi-arid environments between latitudes 19 and 32oS in mainland Australia. It occupies coastal Western Australia from around Port Hedland south to Perth, and stretches eastwards over to Mount Isa in Queensland, and along the western parts of the Great Dividing Range through central Queensland and central western New South Wales, into the northwestern corner of Victoria and the Eyre Peninsula and across the Nullarbor.[34] It commonly cohabits with other species of fairy-wren, including the Purple-backed Fairy-wren (M. lamberti assimilis). White-winged Fairy-wrens often inhabit heathlands or treeless shrublands dominated by saltbush (Atriplex) and small shrubs of the genus Maireana, or grasses such as tussock grass (Triodia), and cane-grass (Zygochloa), as well as floodplain areas vegetated with lignum (Muehlenbeckia).[24][35] Meanwhile, M. l. leucopterus inhabits similar habitats on Dirk Hartog Island and M. l. edouardi does the same on Barrow Island.[22] The White-winged Fairy-wren is replaced to the north of its range on mainland Australia by the Red-backed Fairy-wren.[35]

Behaviour

Hopping, with both feet leaving the ground and landing simultaneously, is the usual form of locomotion, though birds may run while performing the 'Rodent Run Display' detailed below.[36] Its balance is assisted by a proportionally large tail, which is usually held upright and rarely still. The short, rounded wings provide good initial lift and are useful for short flights, though not for extended jaunts.[37]

White-winged Fairy-wrens live in large and complex social groups.[38] Larger clans comprise 2–4 birds, typically consisting of one brown or partially blue male and a breeding female. Nest helpers are birds raised in previous years which remain with the family group after fledging and assist in raising young;[39] they may be male, remaining in brown plumage, or female.[40] Birds in a group roost side-by-side in dense cover as well as engaging in mutual preening.[41] Several subgroups live within one territory and make up a clan, which is presided over by one blue (or black) male who assumes breeding plumage. While the blue male is dominant to the rest of the brown and partially blue males within his clan, he nests with only one female and contributes to the raising of only her young. It is unclear whether or not he copulates and fathers any of the other nests within his territory.[42]

Each clan has a specified area of land that all members contribute to foraging from and defending—although these orders may vary year to year. Frequently, territory sizes, normally 4–6 ha (10–15 acres), are correlated with the abundance of rain and resources in a region; smaller territories occur where insects and resources are plentiful.[24] Additionally, territories expand during the winter months when these birds spend much of their time foraging with the entire clan. White-winged Fairy-wrens occupy much larger territories than other fairy-wren species.[43]

Observed in this species,[42] the 'Wing-fluttering' display is seen in several situations: females responding, and presumably acquiescing, to male courtship displays, juveniles while begging for food, by helpers to older birds, and immature males to senior ones. The fairy-wren lowers its head and tail, outstretches and quivers its wings and holds its beak open silently.[27]

Threats

Adults and their young may be preyed upon by exotic mammalian predators, such as the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) or the feral cat (Felix catus), and native predatory birds, such as the Australian Magpie (Gymnorhina tibicen), butcherbird species (Cracticus spp.), Laughing Kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae), currawongs (Strepera spp.), crows and ravens (Corvus spp.), and shrike-thrushes (Colluricincla spp.), and reptiles such as goannas.[32][44] Both the male and female adult White-winged Fairy-wren may utilise a 'Rodent-run' display to distract predators from nests with young birds. The head, neck and tail are lowered, wings held out and feathers fluffed as the bird runs rapidly and voices a continuous alarm call.[42] Another threat to the birds is from humans: many nests are destroyed during breeding season by human habitation (and even the occasional bird watcher) because the nests are hidden close to the ground and are therefore difficult for passers-by to spot.[11]

Feeding

The White-winged Fairy-wren is primarily insectivorous, a diet which includes small beetles, bugs, moths, praying mantises, caterpillars, and various smaller insects, as well as spiders.[32] The larger insects are typically fed to nestlings by the breeding female and her helpers, including the breeding male. Adults and juveniles forage by hopping along the shrubland floor, and may supplement their diets with seeds and fruits of saltbush (Rhagodia) and goosefoot (Chenopodium) as well as new shoots of samphire.[45] During spring and summer, birds are active in bursts through the day and accompany their foraging with song. Insects are numerous and easy to catch, which allows the birds to rest between forays. The group often shelters and rests together during the heat of the day. Food is harder to find during winter and they are required to spend the day foraging continuously.[41]

Courtship and breeding

Fairy-wrens exhibit one of the highest incidences of extra-pair mating, and many broods are brought up a by male other than the natural father. However, courtship methods among White-winged Fairy-wrens remain unclear. Blue-plumaged males have been seen outside of their territory and in some cases, carrying pink or purple petals, which among other species, advertise the male to neighboring females. In contrast, black-plumaged males on Barrow and Dirk Hartog islands often carry blue petals.[24] While petal-carrying outside of clan territories is indicative of extra-pair copulations, further genetic analysis is necessary.[42]

Another courting display has the male bowing deeply forward facing the female, reaching the ground with his bill and spreading and flattening his plumage in a near-horizontal plane for up to 20 seconds. In this pose, the white plumage forms a striking white band across his darker plumage.[46]

Breeding females begin to build their nests in the spring, constructing domed structures composed of spiderwebs, fine grasses, thistle-down, and vegetable-down, typically 6–14 cm (2⅓–5½ in) tall and 3–9 mm thick.[24] Each nest has a small entrance on one side and they are normally placed in thick shrubs close to the ground. A clutch of 3–4 eggs is generally laid anywhere from September to January, with incubation lasting around 14 days.[42] The White-winged Fairy-wren generally breeds in the spring in the southwest of Western Australia, but is more opportunistic in arid regions of central and northern Australia, with breeding recorded almost any month after a period of rainfall.[47] Incubation is by the breeding female alone, while the breeding male (a brown or blue male) and nest helpers aid in feeding the nestlings. Nestlings remain in the nest for 10–11 days, and fledglings continue to be fed for 3–4 weeks following their departure from the nest. Fledglings then either stay on to help raise the next brood or move to a nearby territory.[40] It is not unusual for a pair bond to hatch and raise two broods in one breeding season, and helpers tend to lessen the stress on the breeding female rather than increase the overall number of feedings.[24] Like other fairy-wrens, the White-winged Fairy-wren is particularly prone to parasitic nesting by the Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo (Chalcites basalis); parasitism by the Shining Bronze-Cuckoo (C. lucidus) and Black-eared Cuckoo (C. osculans) was also rarely recorded.[48]

References

- ^ a b Template:IUCN2006

- ^ Dumont C (1824). "Malurus leucopterus". Dictionnaire des Sciences Naturelles. 30: 118.

- ^ a b c Schodde R (1982). The fairy-wrens: a monograph of the Maluridae. Melbourne: Lansdowne Editions. pp. p. 108. ISBN 0-7018-1051-3.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ a b Liddell, Henry George and Robert Scott (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged Edition). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ^ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 177

- ^ Mack (1934). "A revision of the genus Malurus". Memoirs of the National Museum of Victoria. 8: 100–25.

- ^ a b c Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 178

- ^ Schodde R (The fairy-wrens: a monograph of the Maluridae), p. 108

- ^ Christidis L, Schodde R. 1997, "Relationships within the Australo-Papuan Fairy-wrens (Aves: Malurinae): an evaluation of the utility of allozyme data". Australian Journal of Zoology, 45 (2): 113–129.

- ^ Schodde R (The fairy-wrens: a monograph of the Maluridae), p. 31

- ^ a b Favaloro N (1940). "Notes on the Blue-and-white Wren". Emu. 40 (4): 260–65.

- ^ Sharpe (1879). Catalogue of the Passeriformes, or perching birds, in the collection of the British museum. Cichlomorphae, part 1. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|firt=ignored (help) - ^ Sharpe (1883). Catalogue of the Passeriformes, or perching birds, in the collection of the British museum. Cichlomorphae, part 4. London: Trustees of the British Museum.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|firt=ignored (help) - ^ Sharpe (1903). A handlist of the genera and species of birds. Volume 4. London: British Museum.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|firt=ignored (help) - ^ Schodde (1975). Interim List of Australian Songbirds: passerines. Melbourne: RAOU. OCLC 3546788.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|firat=ignored (help) - ^ Barker, FK (2002). "A phylogenetic hypothesis for passerine birds; Taxonomic and biogeographic implications of an analysis of nuclear DNA sequence data". Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 269: 295–308.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Barker, FK (2004). "Phylogeny and diversification of the largest avian radiation" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101 (30): 11040–11045. Retrieved 2007-10-12.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f Pruett-Jones S, Tarvin KA (2001). "Aspects of the ecology and behaviour of White-winged Fairy-wrens on Barrow Island". Emu. 101 (1): 73–78.

- ^ a b c Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 177–78

- ^ Carter T (1917). "The birds of Dirk Hartog Island and Peron Peninsula, Shark Bay, Western Australia 1916-17. With nomenclature and remarks by Gregory M. Mathews". Ibis series 10. 5: 564–611.

- ^ Campbell AJ (1901). "Description of a new wren or Malurus". Victorian Naturalist. 17: 203–04.

- ^ a b c Rathburn MK, Montgomerie R (2003). "Breeding biology and social structure of White-winged Fairy-wrens (Malurus leucopterus): comparison between island and mainland subspecies having different plumage phenotypes". Emu. 103 (4): 295–306.

- ^ a b Driskell AC, Pruett-Jones S, Tarvin KA, Hagevik S (2002). (abstract) "Evolutionary relationships among blue- and black-plumaged populations of the White-winged Fairy-wren (Malurus leucopterus)". Australian Journal of Zoology. 50 (6): 581–95. doi:10.1071/ZO02019. Retrieved 2008-05-17.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h Rowley I, Russell E (1995). (abstract) "The Breeding Biology of the White-winged Fairy-wren Malurus leucopterus leuconotus in a Western Australian Coastal Heathland". Emu. 95 (3): 175–84. doi:10.1071/MU9950175.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 38

- ^ Wooller RD (1984). "Bill size and shape in honeyeaters and other small insectivorous birds in Western Australia". Australian Journal of Zoology. 32: 657–62.

- ^ a b Rowley & Russell, (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens) p. 77

- ^ a b Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 176

- ^ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 37

- ^ Rowley, Ian (1997). Bird Families of the World: Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. p. 44. ISBN 0-19-854690-4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bennett ATD, Cuthill IC (1994). "Ultraviolet vision in birds: what is its function?". Vision Research. 34 (11): 1471–78. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(94)90149-X. PMID 8023459.

- ^ a b c Tidemann S (1980). "Notes on breeding and social behaviour of the White-winged Fairy-wren Malurus leucopterus". Emu. 80 (3): 157–61.

- ^ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 178–79

- ^ Schodde R (The fairy-wrens: a monograph of the Maluridae), p. 110

- ^ a b Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 179

- ^ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 42

- ^ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 41

- ^ Rowley & Russell (Bird Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 57

- ^ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 88

- ^ a b Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 181

- ^ a b Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 61–62

- ^ a b c d e Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 180

- ^ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 59

- ^ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 121

- ^ Schodde R (The fairy-wrens: a monograph of the Maluridae), p. 111

- ^ Schodde R (The fairy-wrens: a monograph of the Maluridae), p. 112

- ^ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 105

- ^ Rowley & Russell (Families of the World:Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens), p. 119

External links

- The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2000 www.environment.gov.au

- IUCN Red List

- White-winged Fairy-wren videos on the Internet Bird Collection