Operation Auca

Operation Auca was an attempt by five Evangelical Christian missionaries from the United States to make contact with the Huaorani people of the rainforest of Ecuador. The Huaorani, also known as the Aucas (the Quechua word for "naked savages"), were an isolated tribe known for their violence, against both their own people and outsiders who entered their territory. With the intention of being the first Protestants to evangelize the previously unreached Huaorani, the missionaries began making regular flights over Huaorani settlements in September 1955, dropping gifts. After several months of exchanging gifts, on January 2 1956 the missionaries established a camp at "Palm Beach", a sandbar along the Curaray River, a few miles from Huaorani settlements. Their efforts came to an end on January 8 1956, when all five—Jim Elliot, Nate Saint, Ed McCully, Peter Fleming, and Roger Youderian—were attacked and speared by a group of Huaorani warriors. The news of their deaths was broadcast around the world, and Life magazine covered the event with a photo essay.

The deaths of the men galvanized the missionary effort in the United States, sparking an outpouring of funding for evangelization efforts around the world. Their work is still frequently remembered in evangelical publications, and in 2006 was the subject of the film production End of the Spear. Several years after the death of the men, the widow of Jim Elliot, Elisabeth, and the sister of Nate Saint, Rachel, returned to Ecuador as missionaries with the Summer Institute of Linguistics (now SIL International) to live among the Huaorani. This eventually led to the conversion of many, including some of those involved in the killing. While largely eliminating tribal violence, their efforts exposed the tribe to exploitation and increased influence from the outside. This has caused Huaorani culture to begin to disappear, but anthropologists argue over the ultimate effect—some negatively view the missionary work as cultural imperialism, while others contend that the influence has been beneficial for the tribe.

Background

The Huaorani

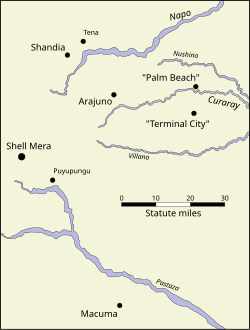

The Huaorani around the time of Operation Auca were a small tribe occupying the jungle of Eastern Ecuador between the Napo and Curaray Rivers, an area of approximately 20,000 square kilometers (7,700 mi²). They numbered approximately 600 people, and were split into three groups, all mutually hostile—the Geketaidi, the Baïidi, and the Wepeidi. They lived on the gathering and cultivation of plant foods like manioc and plantains, as well as fishing and hunting with spear and blowgun. Family units consisted of a man and his wife or wives, their unmarried sons, their married daughters and sons-in-law, and their grandchildren. All of them would reside in a longhouse, which was separated by several miles from another longhouse in which close relatives lived. Marriage was always endogamous and typically between cousins, and arranged by the parents of the young people.[1]

Before their first peaceful contact with outsiders (cowodi) in 1958, the Huaorani fiercely defended their territory. Viewing all cowodi as cannibalistic predators, they killed rubber tappers around the turn of the 20th century and Shell Oil Company employees during the 1940s, in addition to any lowland Quechua or other outsiders who encroached on their land.[2] Furthermore, they were prone to internal violence, often engaging in vengeance killing of other Huaorani. Raids were carried out in extreme anger by groups of men who attacked their victims' longhouse by night and then fled. Attempts to build truces through gifts and exchange of spouses became more frequent as their numbers decreased and the tribes fragmented, but the cycle of violence continued.[3]

The missionaries

Jim Elliot first heard of the Huaorani in 1950 from a former missionary to Ecuador, and soon concluded that God was calling him to Ecuador to evangelize the Huaorani. He began corresponding with his friend Pete Fleming about his desire to minister in Ecuador, and in 1952 the two men set sail for Guayaquil as missionaries with the Plymouth Brethren.[4][5] For six months they lived in Quito with the goal of learning Spanish. They then moved to Shandia, a Quechua mission station deep in the Ecuadorian jungle. There they worked under the supervision of a Mission Aviation Fellowship missionary, Wilfred Tidmarsh, and began exposing themselves to the culture and studying the Quechua language.[6][5]

Another team member was Ed McCully, a man Jim Elliot had met and befriended while both attended Wheaton College. Following graduation, he married Marilou Hobolth and enrolled in a one-year basic medical treatment program at the School of Missionary Medicine in Los Angeles. On December 10 1952, McCully moved to Quito with his family as a Plymouth Brethren missionary, planning to soon join Elliot and Fleming in Shandia. In 1953, however, the station in Shandia was wiped out by a flood, delaying their move until September of that year.[7][5]

The team's pilot, Nate Saint, had served in the military during World War II, receiving flight training as a member of the Army Air Corps.[8] After being discharged in 1946, he too studied at Wheaton College, but quit after a year and joined the Mission Aviation Fellowship in 1948. He and his wife Marj traveled to Ecuador by the end of the year, and they settled at MAF headquarters in Shell Mera. Shortly after his arrival, Saint began transporting supplies and equipment to missionaries spread throughout the jungle. This work ultimately led to his meeting the other four missionaries, who he joined in Operation Auca.[9]

Also on the team was Roger Youderian, a 32-year-old missionary who had been working in Ecuador since 1953. Under the mission board Gospel Missionary Union, he and his wife Barbara and daughter Beth settled in Macuma, a mission station in the southern jungle of Ecuador. There, he and his wife ministered to the Shuar people, learning their language and transcribing it.[10] After working with them for about a year, Youderian and his family began ministering to a tribe related to the Shuar, the Achuar people. He worked with Nate Saint to provide important medical supplies; but after a period of attempting to build relationships with them, he failed to see any positive effect and, growing depressed, considered returning to the United States. However, during this time Saint approached him about joining their team to meet the Huaorani, and he assented.[11]

Initial contact

The first stage of Operation Auca began in September 1955. Saint, McCully, Elliot, and fellow missionary Johnny Keenan decided to initiate contact with the Huaorani and began periodically searching for them by air. By the end of the month, they had identified several clearings in the jungle. Meanwhile, Elliot learned several phrases in the language of the Huaorani from Dayuma, a young Huaorani woman who had left her society and become friends with Rachel Saint, a missionary and the sister of Nate Saint. The missionaries hoped that by regularly giving gifts to the Huaorani and attempting to communicate with them in their language, they would be able to win them over as friends.[12]

Because of the difficulty and risk of meeting the Huaorani on the ground, the missionaries chose to drop gifts to the Huaorani by fixed-wing aircraft. Their drop technique, developed by Nate Saint, involved flying around the drop location in tight circles while lowering the gift from the plane on a rope. This kept the bundle in roughly the same position as it approached the ground. On October 6 1955, Saint made the first drop, releasing a small kettle containing buttons and rock salt. The gift-giving continued during the following weeks, with the missionaries dropping machetes, ribbons, clothing, pots, and various trinkets.[13]

After several visits to the Auca village, which the missionaries called "Terminal City", they observed that the Huaorani seemed excited to receive their gifts. Encouraged, they began using a loudspeaker to shout simple Huaorani phrases as they circled. After several more drops, in November the Huaorani began tying gifts for the missionaries to the line after removing the gifts the missionaries gave them. The men took this as a gesture of friendliness and developed plans for meeting the Huaorani on the ground. Saint soon identified a 200-yard (180 m) sandbar along the Curaray River about 4.5 miles (7 km) from Terminal City that could serve as a runway and camp site, and dubbed it "Palm Beach".[14]

Palm Beach

At this point, Pete Fleming had still not decided to participate in the operation, and Roger Youderian was still working in the jungle farther south. On December 23, the Flemings, Saints, Elliots and McCullys together hatched a plan to land at Palm Beach and build a camp on January 3 1956. They agreed to take weapons, but decided that they would only be used to fire into the air to scare the Huaorani if they attacked. They built a sort of tree house that could be assembled upon arrival, and collected gifts, first aid equipment, and language notes.[15]

By January 2, Youderian had arrived and Fleming had confirmed his involvement, so the five met in Arajuno to prepare to leave the following day. After minor mechanical trouble with the plane, Saint and McCully took off at 8:02 a.m. on January 3 and successfully landed on the sandy beach along the Curaray River. Saint then flew Elliot and Youderian to the camp, and then made several more flights, carrying equipment. After the last delivery, he flew over a Huaorani settlement and, using a loudspeaker, told the Huaorani to visit the missionaries' camp. He then returned to Arajuno, and the next day, he and Fleming flew out to Palm Beach.[16]

First visit

On January 6, after the Americans had spent several days of waiting and shouting basic Huaorani phrases into the jungle, the first Huaorani visitors arrived. A young man and two women emerged on the opposite river bank around 11:15 a.m., and soon joined the missionaries at their encampment.[17] The younger of the two women had come against the wishes of her family, and the man, named Nankiwi, who was romantically interested in her, followed. The older woman (about thirty years old) acted as a self-appointed chaperone.[18] The men gave them several gifts, including a model plane, and the visitors soon relaxed and began conversing freely, apparently not realizing that the men's language skills were weak. Nankiwi, who the missionaries nicknamed "George", showed interest in their aircraft, so Saint took off with him aboard. They first completed a circuit around the camp, but Nankiwi appeared eager for a second trip, so they flew toward Terminal City. Upon reaching a familiar clearing, Nankiwi recognized his neighbors, and leaning out of the plane, wildly waved and shouted to them. Later that afternoon, the younger woman became restless, and though the missionaries offered their visitors sleeping quarters, Nankiwi and the young woman left the beach with little explanation. The older woman apparently had more interest in conversing with the missionaries, and remained there most of the night.[19]

After seeing Nankiwi in the plane, a small group of Huaorani decided to make the trip to Palm Beach, and left the following morning, January 7. On the way, they encountered Nankiwi and the girl, returning unescorted. The girl's brother, Nampa, was furious at this, and to defuse the situation and divert attention from himself, Nankiwi claimed that the foreigners had attacked them on the beach, and in their haste to flee, they had been separated from their chaperone. Gikita, a senior member of the group whose experience with outsiders had taught him that they could not be trusted, recommended that they kill the foreigners. The return of the older woman and her account of the friendliness of the missionaries was not enough to dissuade them, and they soon continued toward the beach.[18]

The attack

On January 8 the missionaries waited, expecting a larger group of Huaorani to arrive sometime that afternoon, if only to get plane rides. Saint made several trips over Huaorani settlements, and on the following morning he noted a group of Huaorani men traveling toward Palm Beach. He excitedly relayed this information to his wife over the radio at 12:30 p.m., promising to make contact again at 4:30 p.m.[20]

The Huaorani arrived at Palm Beach around 3:00 p.m., and in order to divide the foreigners before attacking them, they sent three women to the other side of the river. One, Dawa, remained hidden in the jungle, but the other two showed themselves. Two of the missionaries waded into the water to greet them, but were attacked from behind by Nampa. Apparently attempting to scare him, the first missionary to be speared drew his pistol and began firing. One of these shots mildly injured Dawa, still hidden, and another grazed the missionary's attacker after he was grabbed from behind by one of the women.[21] Accounts differ on the effect of that bullet. Missionaries interpreted the testimonies of Dawa and Dayuma to mean that Nampa was killed months later while hunting, but others, including missionary anthropologist James Yost, came to believe that his death was a result of the bullet wound. Rachel Saint did not accept this, holding that eyewitnesses supported her position, but researcher Laura Rival, a critic of the expedition, suggests that it is now commonly believed among Huaorani that Nampa died of the wound.[22][23] The other missionary in the river, before being speared, desperately reiterated friendly overtures and asked the Huaorani why they were killing them. Meanwhile, the other Huaorani warriors, led by Gikita, attacked the three missionaries still on the beach, killing all three before they had a chance to report the attack over the radio. They then threw the men's bodies and their belongings in the river, and ripped the fabric from their aircraft. They then returned to their village and, anticipating retribution, burned it to the ground and fled into the jungle.[21]

Searching for the missionaries

Not receiving word from Saint at 4:30 p.m. immediately caused his wife Marj to worry, but she did not tell anyone about the lack of communication until that evening. The next morning, January 9, Johnny Keenan flew to the camp site, and at 9:30 a.m. he reported via radio to the wives that the plane was stripped of its fabric and that the men were not there. The Commander in Chief of the Caribbean Command, Lieutenant General William K. Harrison, was contacted, and Quito-based radio station HCJB released a news bulletin saying that five men were missing in Huaorani territory. Soon, aircraft from the United States Air Rescue Service in Panama were flying over the jungle, and a ground search party consisting of missionaries and military personnel was organized. The first two of the bodies were found on January 11, and on Thursday, Ed McCully's body was identified by a group of Quechua. They took his watch as evidence of the finding but did not move his body from its location on the bank of the Curaray. It later washed away, and two more bodies were found on January 12. The searchers hoped that one of the unidentified bodies would be McCully, thinking that perhaps one of the men had escaped. However, on January 13, all four of the bodies found were positively identified and McCully's body was not among them, confirming that all five were dead. In the midst of a tropical storm, they were buried in a common grave at Palm Beach on January 14 by members of the ground search party.[24][25]

Aftermath

Life magazine covered the deaths of the men with a photo essay, including photographs by Cornell Capa and some taken by the five men before their deaths. The ensuing worldwide publicity gave several missionary organizations significant political power, especially in the United States and Latin America. Most notable among these was the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL), the organization for which both Elisabeth Elliot and Rachel Saint worked. Because of the martyrdom of her brother, Saint considered herself spiritually bonded to the Huaorani, believing that what she saw as his sacrifice for the Huaorani was symbolic of Christ's death for the salvation of humanity. In 1957, Saint and her Huaorani companion Dayuma toured across the United States and appeared on the television show This Is Your Life. The two also appeared in a Billy Graham crusade in New York City, contributing to Saint's increasing popularity among evangelical Christians and generating significant monetary donations for SIL.[26]

Saint and Elliot returned to Ecuador to work among the Huaorani, establishing a camp called Tihueno near a former Huaorani settlement. Rachel Saint and Dayuma became bonded in Huaorani eyes through their shared mourning and Rachel's adoption as a sister of the Dayuma, taking the name Nemo from the latter's deceased youngest sister. The first Huaorani to settle there were primarily women and children from a Huaorani group called the Guiquetairi, but in 1968 an enemy Huaorani band known as the Baihuari joined them. Elliot had returned to the United States in the early 1960s, so Saint and Dayuma worked to alleviate the resulting conflict. They succeeded in securing cohabitation of the two groups by overseeing numerous cross-band weddings, leading to an end of inter-clan warfare but obscuring the cultural identity of each group.[27]

Saint and Dayuma, in conjunction with SIL, negotiated the creation of an official Huaorani reservation in 1969, consolidating the Huaorani and consequently opening up the area to commerce and oil exploration. By 1973, over 500 people lived in Tihueno, of which more than half had arrived in the previous six years. The settlement relied on missions aid from SIL, and as a Christian community set up by missionaries, all those living there were obliged to follow specific rules completely foreign to traditional Huaorani culture, most notably the prohibitions of killing and polygamy. By the early 1970s, SIL began to question whether their impact on the Huaorani was positive, so they sent James Yost, a staff anthropologist, to assess the situation. He found extensive economic dependence and increasing cultural assimilation, and as a result, SIL ended its support of the settlement in 1976, leading to its disintegration and the dispersion of the Huaorani into the surrounding area. SIL had hoped that the Huaorani would return to the isolation in which they had lived twenty years prior, but instead they sought out contact with the outside world, forming villages of which many have been recognized by the Ecuadorian government.[28][29]

Legacy

Christian views

Among evangelical Christians, the five men are commonly considered martyrs and missionary heroes. Books have been written about them by numerous biographers, most notably Elisabeth Elliot. Anniversaries of their deaths have been accompanied by stories in major Christian publications,[30] and their story, as well as the subsequent acceptance of Christianity among the Huaorani, has been turned into several motion pictures. These include the documentary Beyond the Gates of Splendor (featuring interviews with some of the Huaorani and surviving family members of the missionaries) and the 2006 dramatic production End of the Spear, which grossed over $12 million.[31] Even so, Christians have noted with concern the disintegration of traditional Huaorani culture and westernization of the tribe, beginning with Nate Saint's own journal entry in 1955 and continuing through today. However, many continue to view as positive both Operation Auca and the subsequent missionary efforts of Rachel Saint, mission organizations such as Mission Aviation Fellowship, Wycliffe Bible Translators, HCJB World Radio, Avant Ministries (formerly Gospel Missionary Union), and others. Specifically, they note the decline in violence among tribe members, numerous conversions to Christianity, and growth of the local church.[32][33]

Anthropologist views

Anthropologists generally have less favorable views of the missionary work begun by Operation Auca, viewing the intervention as the cause for the recent and widely recognized decline of Huaorani culture. Leading Huaorani researcher Laura Rival says that the work of the SIL "pacified" the Huaorani during the 1960s, and argues that missionary intervention caused significant changes in fundamental components of Huaorani society. Prohibitions of polygamy, violence, chanting, and dancing were directly contrary to cultural norms, and the relocation of Huaorani and subsequent intermarrying of previously hostile groups eroded cultural identity.[27] Others are somewhat less negative—Brysk, after noting that the work of the missionaries opened the area to outside intervention and led to the deterioration of the culture, says that the SIL also informed the Huaorani of their legal rights and taught them how to protect their interests from developers.[34] Boster goes even further, suggesting that the "pacification" of the Huaorani was a result of "active effort" by the Huaorani themselves, not the result of missionary imposition. He argues that Christianity served as a way for the Huaorani to escape the cycle of violence in their community, since it provided a motivation to abstain from killing.[35]

References

- Boster, James S. (2003). "Rage, Revenge, and Religion: Honest Signaling of Aggression and Nonaggression in Waorani Coalitional Violence" (PDF). Ethos. 31 (4): 471–494. doi:10.1525/eth.2003.31.4.471.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Brysk, Alison (2004). "From Civil Society to Collective Action". In Edward L. Cleary and Timothy J. Steigenga (ed.). Resurgent Voices in Latin America. London: Rutgers University. pp. 25–42. ISBN 0-8135-3460-7.

- Colby, Gerard (1995). Thy Will Be Done. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-016764-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Elliot, Elisabeth (2005). Through Gates of Splendor. Wheaton, Illinois: Tyndale. ISBN 0-8423-7151-6.

- Hitt, Russell (1959). Jungle Pilot: The Life and Witness of Nate Saint. New York: Harper.

- "5 U.S. Missionaries Are Believed Slain". New York Times. January 12, 1956. p. 3.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "5 U.S. Missionaries Lost; Jungle Murder Feared". New York Times. January 11, 1956. p. 4.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Four Bodies Found in Ecuador". New York Times. January 13, 1956. p. 5.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Rainey, Clint (2006). "Five-Man Legacy". World (January 28, 2006): 20–27.

- Rival, Laura M. (2002). Trekking through history: the Huaorani of Amazonian Ecuador. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11844-9.

- Saint, Steve (1996). "Did They Have to Die?". Christianity Today (September 16, 1996): 20–27.

- Saint, Steve (2007). End of the Spear. Saltriver. ISBN 084238488X.

- Stoll, David (1982). Fishers of Men or Founders of Empire?. London: Zed. ISBN 0-86232-111-5.

- Stoll, David (1990). Is Latin America Turning Protestant?. Los Angeles: University of California. ISBN 0-520-06499-2.

Notes

- ^ Boster, 473–75.

- ^ Rival, 37–38.

- ^ Boster, 473, 475, 480.

- ^ Elliot, 19–21, 24.

- ^ a b c Stoll (1982), 282–83.

- ^ Elliot, 25–26, 28–32.

- ^ Elliot, 48, 53–54.

- ^ Hitt, 65.

- ^ Hitt, 94, 136–45, 265.

- ^ Elliot, 73–79.

- ^ Elliot, 81, 92–94, 151–54.

- ^ Elliot, 128–33.

- ^ Elliot, 134–43, 149–50.

- ^ Elliot, 146–48, 156, 161, 163.

- ^ Elliot, 173–74.

- ^ Elliot, 177–83.

- ^ Elliot, 189.

- ^ a b Saint, 25.

- ^ Elliot, 190–92.

- ^ Elliot, 193–94.

- ^ a b Saint, 26–27.

- ^ Rival, 158.

- ^ Stoll (1982), 305–07.

- ^ Elliot, 195–200, 233–39.

- ^ New York Times articles

- ^ Colby, 287–90.

- ^ a b Rival, 157–59.

- ^ Rival, 158–61.

- ^ Stoll (1982), 296–305.

- ^ Saint and Rainey.

- ^ "End of the Spear (2006)". Boxofficemojo.com. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ^ Elliot, 157.

- ^ Rainey, 18–21.

- ^ Brysk, 37–38.

- ^ Boster, 480–82.

Further reading

- "'Go Ye and Preach the Gospel' Five Do and Die". Life Magazine. January 30, 1956. p. 10–19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Ziegler-Otero, Lawrence (2004). Resistance In An Amazonian Community: Huaorani Organizing Against The Global Economy. New York / Oxford: Berghahn. ISBN 1-57181-448-5. This book gives details about the collusion of the Summer Institute of Linguistics in general and Rachel Saint in particular with US oil companies and the Ecuadorian military.

External links

- Remembering Five Missionary Martyrs (Intervarsity Christian Fellowship)

- Five Missionary Martyrs (Moments Media)

- IMDb page for movie based on these events, titled "End of the Spear" (2006)

- Movie based on these and subsequent events, titled "Trinkets and Beads" (1996) (First Run / Icarus Films)

- More Than Meets the Eye History and The End of the Spear. (Christianity Today)