Oliver Sacks

Oliver Sacks | |

|---|---|

Oliver Sacks in 2005. | |

| Born | July 9, 1933 |

| Years active | 1966 - present |

| Known for | popular series of books about cases and patients |

| Medical career | |

| Profession | doctor |

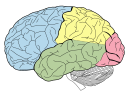

| Sub-specialties | neurology |

| Neuropsychology |

|---|

|

Oliver Wolf Sacks (born July 9, 1933, London), is a United States-based British neurologist who has written popular books about his patients, the most famous of which is Awakenings, which was adapted into a film starring Robin Williams and Robert De Niro.

Sacks considers that his literary style follows the tradition of 19th-century "clinical anecdotes," a literary style that included informal case histories, following the writings of Alexander Luria.[1] Sacks is a childhood friend of Jonathan Miller[2] and a cousin of Robert Aumann and the late Abba Eban.[3]

In 2007,[4] Columbia University, where Sacks serves as Professor of Neurology and Psychiatry, appointed Sacks as "its first Columbia artist, a newly created designation."

Biography

The fourth and youngest child of a prosperous North London Jewish medical family: his father Sam a doctor, his mother Elsie a surgeon. Aged six in 1939, his parents sent him to a boarding school in the Midlands for four years to keep him out of harm's way.[2] During his childhood, Sacks was passionate about chemistry and tried to collect samples of all the elements and did many experiments in his home laboratory. He derived much inspiration from his uncle Dave, as told in Sacks' autobiographical book Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood.

Sacks earned a Bachelor of Arts (BA) in physiology and biology from The Queen's College, Oxford University in 1954, he proceeded to graduate with a Master of Arts (MA) from the same college in 1958, furthermore he also graduated with a MB ChB in 1958, in so doing he qualified as a doctor. In 1960, he went to Canada on holiday, and on arrival sent his parents a one-word telegram: "Staying". Sacks hitch-hiked to the Rockies, and then down to San Francisco, where he fell in with the poet and motorcycle enthusiast, Thom Gunn.[2] Sacks became a resident in neurology at UCLA.

After converting his British qualifications to American recognition (i.e. an MD as opposed to MB ChB), Sacks moved to New York where he has lived since 1965, and taken twice weekly therapy sessions since 1966.[2]

In 1966, Sacks began working as a consulting neurologist at Beth Abraham Hospital (now Beth Abraham Health Services), a chronic care facility in the Bronx. It was here that he first encountered a group of patients, many of whom had spent decades unable to initiate movement due to the devastating effects of the 1920s sleeping sickness, encephalitis lethargica.[5] His work at Beth Abraham provided the foundation on which the Institute for Music and Neurologic Function (IMNF), where Sacks is currently an honorary medical advisor, is built. In 2000, he was honored with the IMNF’s Music Has Power Award for his contributions towards advancing knowledge of the power of music to awaken and heal, and again in 2006 to commemorate his 40th year at Beth Abraham and recognize his dedication to its patients.

Sacks was formerly a clinical professor of neurology at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, adjunct professor of neurology at the New York University School of Medicine, where he worked for over 43 years. On September 1, 2007, he became professor of clinical neurology and clinical psychiatry at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, leading that department while serving as Columbia University's first "artist"—a new position the university hopes will help bridge the gap between disciplines such as medicine, law, and economics.[4] He remains a consultant neurologist to the Little Sisters of the Poor, and maintains a practice in New York City.

Sacks describes his cases with little clinical detail, concentrating on the experiences of the patient (in the case of his A Leg to Stand On, the patient was himself). The patients he describes are often able to adapt to their situation in different ways despite the fact that their neurological conditions are usually considered incurable.[6] His most famous book, Awakenings, upon which the movie of the same name is based, describes his experiences using the new drug L-Dopa on Beth Abraham post-encephalitic patients in 1969. Awakenings was also the subject of the first film made in the British television series Discovery.

In his other books, he describes cases of Tourette syndrome and various effects of Parkinson's disease. The title article of The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat is about a man with visual agnosia and was the subject of a 1986 opera by Michael Nyman. The title article of An Anthropologist on Mars is about Temple Grandin, a professor with high-functioning autism. In his book The Island of the Colour-blind he describes the Chamorro people of Guam, who have a high incidence of a form of ALS known as Lytico-bodig (a devastating combination of ALS, dementia, and parkinsonism). Along with Paul Cox, Sacks is responsible for the resurgence in interest in the Guam ALS cluster, and has published papers setting out an environmental cause for the cluster, namely toxins such as beta-methylamino L-alanine (BMAA) from the cycad nut accumulating by biomagnification in the flying fox bat.[7][8]

Sacks's writings have been translated into 21 languages, including Catalan, Finnish, and Turkish. He was awarded the Lewis Thomas Prize for Writing about Science in 2001. Oxford University awarded him an honorary Doctor of Civil Law degree in June 2005. In March 2006, he was one of 263 doctors who published an open letter in The Lancet criticizing American military doctors who administered or oversaw the force-feeding of Guantanamo detainees who had committed themselves to hunger strikes.[9]

Books

- Migraine (1970)

- Awakenings (1973)

- A Leg to Stand On (1984) (Sacks' own experience of losing the control of one of his legs after an accident.)

- The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (1985)

- Seeing Voices: A Journey into the Land of the Deaf (1989). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06083-0.

- An Anthropologist on Mars (1995)

- The Island of the Colorblind (1997) (total congenital color blindness in an island society)

- Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood (2001)

- Oaxaca Journal (2002)

- Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain (2007)

Essays and articles

- article in TATE ETC. Summer 2007 including exclusive stereograph of his first photograph, taken at age 12

- "The Mind's Eye (Oliver Sacks)" (positive experiences of blind people) - published in "The Best American Essays 2004", Ed. Robert Atwan

- New York Times Op-Ed by Oliver Sacks regarding the Island of Stability theory

Television series

References

- ^ All in the Mind (2 April 2005). "The Inner Life of the Broken Brain: Narrative and Neurology". Radio National.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d Andrew Brown (5 March 2005). "Oliver Sacks Profile: Seeing double". The Guardian.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Alden Mudge (November 2001). "Chemical reaction: Oliver Sacks finds cosmic order in the elements". BookPage.

- ^ a b Motoko Rich (1 September 2007). "Oliver Sacks Joins Columbia Faculty as 'Artist'". The New York Times.

The appointment grew out of conversations that Dr. Sacks had with several people, including Eric Kandel, a Nobel laureate in medicine and a professor at Columbia, and Gregory Mosher, director of the Arts Initiative at Columbia, which aims to incorporate an interdisciplinary approach to the arts into the undergraduate experience.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Music Has Power Awards Event Journal, Institute for Music and Neurologic Function, November 2006

- ^ Sacks, Oliver (1996-01-12) [1995]. "Preface". An Anthropologist on Mars (New Ed ed.). London: Picador. pp. xiii–xviii. ISBN 0-330-34347-5.

The sense of the brain's remarkable plasticity, its capacity for the most striking adaptations, not least in the special (and often desperate) circumstances of neural or sensory mishap, has come to dominate my own perception of my patients and their lives.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Occurrence of beta-methylamino-l-alanine (BMAA) in ALS/PDC patients from Guam, National Institutes of Health, October 11 2004

- ^ Cycad neurotoxins, consumption of flying foxes, and ALS-PDC disease in Guam, National Institutes of Health, November 26 2002

- ^ Forcefeeding and restraint of Guantanamo Bay hunger strikers, The Lancet, Volume 367, Number 9513, March 11 2006.

External links

- Oliver Sacks website

- 1989 audio interview with Oliver Sacks at Wired for Books.org by Don Swaim

- Wired article (04/2002)

- New York Times Op-Ed piece about encephalitis lethargica.

- Questionable Aspects of Oliver Sacks' (1985) Report.

- 2007 video of Oliver Sacks discussing his book Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain (10/27/2007)

- The Musical Mystery Musicophilia review by Colin McGinn from The New York Review of Books

- Articles needing cleanup from May 2008

- Cleanup tagged articles without a reason field from May 2008

- Wikipedia pages needing cleanup from May 2008

- 1933 births

- Living people

- British Jews

- English Jews

- People from London

- Alumni of The Queen's College, Oxford

- British neurologists

- British neuroscientists

- Members of The American Academy of Arts and Letters

- Columbia University faculty