Sino-French War

| Sino-French War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The French taking Bac Ninh in 1884. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

Black Flag Army | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 15,000 to 20,000 soldiers | 25,000 to 35,000 soldiers (from the provinces of Guangdong, Guangxi, Fujian, Zhejiang and Yunnan) | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 2,100 killed or wounded | 10,000 killed or wounded | ||||||||

The Sino-French War (Chinese: 中法战争, French: guerre franco-chinoise) was a limited conflict fought between August 1884 and April 1885 to decide whether France should replace China in control of Tonkin (northern Vietnam). As the French achieved their war aims, they are usually considered to have won the war. But the French triumph was marred by a number of defeats, and the Chinese armies performed rather better than they did in China’s other nineteenth-century foreign wars. The war hastened the emergence of a strong nationalist movement in China, and some Chinese scholars have even hailed the Sino-French War as ‘the Qing dynasty’s sole victory in arms against a foreign opponent'.

Prelude

French interest in Tonkin dated from the 1860s, when France annexed several Annamese provinces in Cochin China, laying the foundations for its later colonial empire in Indochina. French explorers followed the course of the Red River through Tonkin to its source in Yunnan, arousing hopes that an extremely profitable overland trade route could be established with China, bypassing the treaty ports of the Chinese coastal provinces. The main obstacle to the realisation of this dream was the Black Flag Army, a well-organized bandit force under a formidable leader, Liu Yongfu, which had carved out a virtually-independent kingdom in upper Tonkin, astride the course of the Red River around Laokay on the Annam-Yunnan border.

Henri Rivière's Intervention in Tonkin

French intervention in Tonkin was precipitated by Commandant Henri Rivière, who was sent with a small French military force to Hanoi at the end of 1881 to investigate Annamese complaints against the activities of French merchants. In defiance of the instructions of his superiors, Rivière stormed the citadel of Hanoi on 25 April 1882.

There had recently been a change of government in France, and the new administration of Jules Ferry was strongly in favour of colonial expansion. It therefore decided to back Rivière up. The Annamese government, unable to confront Rivière with its own ramshackle army, enlisted the help of Liu Yongfu, whose well-trained and seasoned Black Flag soldiers were to prove a thorn in the side of the French. The Annamese also bid for Chinese support. Annam had long been a tributary of China, and there were Chinese garrisons in a number of towns in Tonkin. China agreed to arm and support the Black Flags and to covertly oppose French operations in Tonkin.

The Black Flags had already inflicted one humiliating defeat on a French force commanded by lieutenant de vaisseau Francis Garnier in 1873. Like Rivière in 1882, Garnier had exceeded his instructions and attempted to intervene militarily in Tonkin. Liu Yongfu had been called in by the Annamese government, and ended a remarkable series of French victories against the Annamese by defeating Garnier’s small French force beneath the walls of Hanoi. Garnier was killed in this battle, and the French government later disavowed his expedition.

On 27 March 1883, to secure his line of communications from Hanoi to the coast, Rivière captured the citadel of Nam-Dinh. Taking advantage of Rivière’s absence, the Black Flags and Annamese made an attack on Hanoi, but they were repulsed by chef de bataillon Berthe de Villers in an engagement at Gia-Cuc on 28 March.

Confrontation between France and China

On 10 May 1883 Liu Yongfu challenged the French to battle in a taunting message widely placarded on the walls of Hanoi. On 19 May Rivière marched out of Hanoi to attack the Black Flags. His small force (around 450 men) advanced without proper precautions, and blundered into a well-prepared Black Flag ambush at Paper Bridge (Pont de Papier), a few miles to the west of Hanoi. The French were surrounded and routed, and were only with difficulty able to fall back to Hanoi. Rivière and several other senior officers were killed in the action.

Rivière’s death produced an angry reaction in France. Reinforcements were rushed to Tonkin, a threatened attack by the Black Flags on Hanoi was averted, and the military situation was stabilised. In August 1883 Admiral Amédée Courbet, who had recently been appointed to the command of the newly-formed Tonkin Coasts Naval Division, stormed the Thuan-An forts which guarded the approaches to the Annamese capital Hue, and forced the Annamese government to sign the Treaty of Hue, placing Tonkin under French protection. At the same time the new commander of the Tonkin expeditionary corps, General Bouët, attacked the Black Flag positions at Phu-Hoai (15 August) and Palan (1 September). The French attacks achieved only limited success, but severe flooding later forced Liu Yongfu to abandon his defences and fall back to the fortified city of Sontay, several miles to the west.

The French prepared for a major offensive at the end of the year to annihilate the Black Flags, and tried to persuade China to withdraw its support for Liu Yongfu, while attempting to win the support of the other European powers for the projected offensive. However, negotiations in July 1883 between the French minister Arthur Tricou and Li Hongzhang broke down, largely due to the bullying tactics employed by Tricou. Jules Ferry and the French foreign minister Paul-Armand Challemel-Lacour met a number of times in the summer and autumn of 1883 with Marquis Zeng Jize, the Chinese minister to Paris, but these parallel diplomatic discussions also proved abortive. The Chinese stood firm, and refused to withdraw substantial garrisons of Chinese regular troops from Sontay, Bacninh and Langson, despite the likelihood that they would be shortly engaged in battle against the French.

Undeclared War

Sontay and Bacninh

The French accepted that an attack on Liu Yongfu would probably result in an undeclared war with China, but calculated that a quick victory in Tonkin would force the Chinese to accept a fait accompli. Command of the Tonkin campaign was entrusted to Admiral Courbet, who struck at Sontay in December 1883. The Black Flags fought ferociously to defend the city, abetted by the garrison of Chinese regular troops, but were overwhelmed by the superior French artillery. Sontay was stormed by the French on 16 December.

The fighting at Sontay took a terrible toll of the Black Flags, and in the opinion of some observers broke them once and for all as a serious fighting force. Liu Yongfu felt that he had been deliberately left to bear the brunt of the fighting by his Chinese allies, and determined never again to expose his troops so openly. In March 1884 the French renewed their offensive under the command of General Charles-Théodore Millot, who took over responsibility for the land campaign from Admiral Courbet after the fall of Sontay. Reinforcements from France and the African colonies had now raised the strength of the Tonkin expeditionary corps to over 10,000 men, and Millot organised this force into two brigades. The 1st Brigade was commanded by General Louis Brière de l’Isle, who had earlier made his reputation as governor of Senegal, and the 2nd Brigade was commanded by the charismatic young Foreign Legion general François de Négrier, who had recently quelled a serious Arab rebellion in Algeria. The French target was Bacninh, garrisoned by a strong force of regular Chinese troops of the Guangxi Army[1]. Morale in the Chinese army was low, and Liu Yongfu was careful to keep his experienced Black Flags out of danger. Millot bypassed Chinese defences to the southwest of Bacninh, and assaulted the city on 12 March from the southeast, with complete success. The Guangxi Army put up a feeble resistance, and the French took the city with ease, capturing large quantities of ammunition and a number of brand new Krupp cannon.

The Tientsin Accord

The defeat at Bacninh, coming close on the heels of the fall of Sontay, strengthened the hand of the moderate element in the Chinese government and temporarily discredited the extremist 'Purist' party led by Zhang Zhidong, which was agitating for a full-scale war against France. Further French successes in the spring of 1884, including the capture of Hung-Hoa and Thai-Nguyen, convinced the Empress Dowager Cixi that China should come to terms, and an accord was reached between France and China in May. The negotiations took place in Tianjin [Tientsin]. Li Hongzhang, the leader of the Chinese moderates, represented China; and Captain François-Ernest Fournier, commander of the French warship Volta, represented France. The Tientsin Accord, concluded on 11 May 1884, provided for a Chinese troop withdrawal from Tonkin in return for a comprehensive treaty that would settle details of trade and commerce between France and China and provide for the demarcation of its disputed border with Annam.

Fournier was no diplomat, and the Accord contained several loose ends. Crucially, it failed to explicitly state a deadline for the Chinese troop withdrawal from Tonkin. The French asserted that the troop withdrawal was to take place immediately, while the Chinese argued that the withdrawal was contingent upon the conclusion of the comprehensive treaty. On this occasion, the French were in the right. The Chinese stance was an ex post facto rationalisation, designed to justify their unwillingness or inability to put the terms of the accord into effect. The accord was extremely unpopular in China, and provoked an immediate backlash. The war party called for Li Hongzhang's impeachment, and his political opponents intrigued to have orders sent to the Chinese troops in Tonkin to hold their positions.

The Bac-Le Ambush

Li Hongzhang hinted to the French that there might be difficulties in enforcing the accord, but nothing specific was said. The French assumed that the Chinese troops would leave Tonkin as agreed, and made preparations for occupying Langson and other cities up to the Chinese border. In early June 1884 a French column under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Alphonse Dugenne advanced to occupy Langson. On 23 June, near the small town of Bac-Le, the French encountered a strong detachment of the Guangxi Army ensconced in a defensive position behind the Song-Thuong River. In view of the diplomatic significance of this discovery, Dugenne should have reported the presence of the Chinese force to Hanoi and waited for further instructions. Instead, he gave the Chinese an ultimatum, and on their refusal to withdraw resumed his advance. The Chinese opened fire on the advancing French, precipitating a two-day battle in which Dugenne’s column was encircled and seriously mauled. Dugenne eventually fought his way out of the Chinese encirclement and extricated his small force.

When news of the 'Bac-Le Ambush' reached Paris, there was fury at what was perceived as blatant Chinese treachery. Ferry’s government demanded an apology, an indemnity, and the immediate implementation of the terms of the Tianjin Accord. The Chinese government agreed to negotiate, but refused to apologise or pay an indemnity. The mood in France was against compromise, and although negotiations continued throughout July, Admiral Courbet was ordered to take his squadron to Fuzhou [Foochow]. He was instructed to prepare to attack the Chinese fleet in the harbour and to destroy the Foochow Navy Yard. Meanwhile, as a preliminary demonstration of what would follow if the Chinese were recalcitrant, Rear Admiral Sebastian Lespès destroyed three Chinese shore batteries in the port of Jilong in northern Formosa (Taiwan) by naval bombardment on 5 August. The French put a landing force ashore to occupy Jilong and the nearby coal mines at Beidao, as a ‘pledge’ (gage) to be bargained against a Chinese withdrawal from Tonkin, but the arrival of a large Chinese army under the command of the imperial commissioner Liu Mingchuan forced it to re-embark on 6 August.

The Sino-French War, August 1884 to April 1885

Operations of Admiral Courbet's Squadron

Fuzhou and the Min River

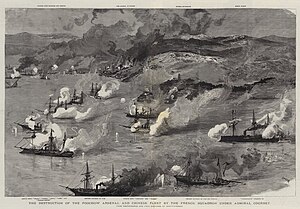

Negotiations between France and China broke down in mid-August, and on 22 August Courbet was ordered to attack the Chinese fleet at Fuzhou. In the Battle of Foochow (also known as the Battle of the Pagoda Anchorage) on 23 August 1884, the French took their revenge for the Bac-Le Ambush. In a two-hour engagement watched with professional interest by neutral British and American vessels (the battle was one of the first occasions on which the spar torpedo was successfully deployed), Courbet's Far East squadron annihilated China's outclassed Fujian fleet and severely damaged the Foochow Navy Yard. Nine Chinese ships were sunk in less than an hour, including the corvette Yangwu, the flagship of the Fujian fleet. Chinese losses may have amounted to 3,000 dead, while French losses were minimal. Courbet then successfully withdrew down the Min River to the open sea, destroying several Chinese shore batteries from behind as he took the French squadron through the Ming'an and Jinpai passes.

French Occupation of Jilong

The French attack at Fuzhou effectively ended diplomatic contacts between France and China for the time being. Although neither country declared war, the dispute would now be settled on the battlefield. The French decided to put pressure on China by landing an expeditionary corps in northern Formosa to seize Jilong and Danshui, redeeming the failure of 6 August and finally winning the ‘pledge’ they sought.

On 1 October Lieutenant-Colonel Bertaux-Levillain landed at Jilong with a force of 1,800 marine infantry, forcing the Chinese to withdraw to strong defensive positions which had been prepared in the surrounding hills. The French force was too small to advance beyond Jilong, and the Beidao coal mines remained in Chinese hands. Meanwhile, after an ineffective naval bombardment on 2 October, Admiral Lespès attacked the Chinese defences at Danshui with 600 sailors from his squadron’s landing companies on 8 October, and was decisively repulsed by forces under the command of the Fujianese general Sun Kaihua. As a result of this reverse, French control over Formosa was limited merely to the town of Jilong. This achievement fell far short of what had been hoped for.

Blockade of Formosa

Towards the end of 1884 the French were able to enforce a limited blockade of the northern Formosan ports of Jilong and Danshui and the southern ports of Taiwanfu (Tainan) and Takao (Gaoxiong). In early January 1885 the Formosa expeditionary corps, now under the command of Colonel Duchesne, was substantially reinforced with two battalions of infantry, bringing its total strength to around 4,000 men. Meanwhile, drafts from the Hunan and Anhui Armies had brought the strength of Liu Mingchuan’s defending army to around 25,000 men. Although severely outnumbered, the French captured a number of minor Chinese positions to the southeast of Jilong at the end of January 1885, but were forced to halt offensive operations in February due to incessant rain.

Shipu Bay, Zhenhai Bay and the Rice Blockade

Although the Formosa expeditionary corps remained confined in Jilong, the French scored important successes elsewhere in the spring of 1885. Courbet’s squadron had been reinforced substantially since the start of the war, and he now had considerably more ships at his disposal than in October 1884. In early February 1885 part of his squadron left Jilong to head off a threatened attempt by part of the Chinese Southern Seas fleet to break the French blockade of Formosa. On 11 February Courbet's task force met the cruisers Kaiji, Nanchen and Nanrui, three of the most modern ships in the Chinese fleet, near Shipu Bay, accompanied by the frigate Yuyuan and the corvette Chengching. The Chinese scattered at the French approach, and while the three cruisers successfully made their escape, the French succeeded in trapping Yuyuan and Chengching in Shipu Bay. On the night of 14 February, in the Battle of Shipu, they destroyed both ships in a daring torpedo attack.

Courbet followed up this success on 1 March by locating Kaiji, Nanchen and Nanrui, which had taken refuge with four other Chinese warships in Zhenhai Bay, near the port of Ningbo. Courbet considered forcing the Chinese defences, but finally decided to guard the entrance to the bay to keep the enemy vessels bottled up there for the duration of hostilities. A brief and inconclusive skirmish between the French cruiser Nielly and the Chinese shore batteries on 1 March enabled the Chinese general Ouyang Lijian, charged with the defence of Ningbo, to claim the so-called 'Battle of Zhenhai' as a defensive victory. The French also began to implement a 'rice blockade' of the Yangzi River, hoping to bring the Qing court to terms by provoking serious rice shortages in northern China.

Operations in Tonkin

French Victories in the Delta

Meanwhile, the French army in Tonkin was also putting severe pressure on the Chinese forces and their Black Flag allies. General Millot, whose health was failing, resigned as general-in-chief of the Tonkin expeditionary corps in early September 1884 and was replaced by General Brière de l’Isle, the senior of his two brigade commanders. Brière de l’Isle identified large detachments of the Guangxi Army moving south through the Luc-Nam valley in late September 1884, and launched a spoiling offensive in early October. General de Négrier advanced north with three French columns, and decisively defeated the separated detachments of the Guangxi Army in engagements at Lam (6 October), Kep (8 October) and Chu (12 October). The second of these engagements was marked by bitter close-quarter fighting between French and Chinese troops, and de Négrier's soldiers suffered heavy casualties storming the fortified village of Kep. The exasperated victors shot or bayoneted scores of wounded Chinese soldiers after the battle, and reports of French atrocities at Kep shocked public opinion in Europe. In fact, prisoners were rarely taken by either side during the Sino-French War, and the French were equally shocked by the Chinese habit of paying a bounty for severed French heads.

In the wake of these French victories the Chinese fell back to Bac-Le and Dong-Song, and de Négrier established important forward positions at Kep and Chu, which threatened the Guangxi Army's base at Langson. Chu was only a few miles southwest of the Guangxi Army's advanced posts at Dong-Song, and on 16 December a strong Chinese raiding detachment ambushed two companies of the Foreign Legion just to the east of Chu, at Ha-Ho. The legionnaires fought their way out of the Chinese encirclement, but suffered a number of casualties and had to abandon their dead on the battlefield. De Négrier immediately brought up reinforcements and pursued the Chinese, but the raiders made good their retreat to Dong-Song.

Shortly after the October engagements against the Guangxi Army Brière de l’Isle took steps to resupply the western outposts of Hung-Hoa, Thai-Nguyen and Tuyen-Quan, which were coming under increasing threat from Liu Yongfu’s Black Flags and Tang Jingsong’s Yunnan Army. On 19 November a column making for Tuyen-Quan under the command of Colonel Duchesne was ambushed in the Yu-Oc gorge by the Black Flags but was able to fight its way through to the beleaguered post. The French also sealed off the eastern Delta from raids by Chinese guerillas based in Guangdong by occupying Tien-Yen, Dong-Trieu and other strategic points, and by blockading the Cantonese port of Beihai (Pak-Hoi). They also conducted sweeps along the lower course of the Red River to dislodge Annamese guerilla bands from bases close to Hanoi. These operations enabled Brière de l’Isle to concentrate the bulk of the Tonkin expeditionary corps around Chu and Kep at the end of 1884, to advance on Langson as soon as the word was given.

The Langson Campaign

French strategy in Tonkin was the subject of a bitter debate in the Chamber of Deputies in late December 1884. The army minister General Jean-Baptiste-Marie Campenon argued that the French should consolidate their hold on the Delta. His opponents urged an all-out offensive to throw the Chinese out of northern Tonkin. The debate culminated in Campenon’s resignation and his replacement as army minister by the hawkish General Lewal, who immediately ordered Brière de l’Isle to capture Langson. The campaign would be launched from the French forward base at Chu, and on 3 and 4 January 1885 General de Négrier attacked and defeated a substantial detachment of the Guangxi Army that had concentrated around the nearby village of Nui-Bop to try to disrupt the French preparations. De Nègrier's victory at Nui-Bop, won at odds of just under one to ten, was regarded by his fellow-officers as the most spectacular professional triumph of his career.

It took the French a month to complete their preparations for the Langson campaign. Finally, on 3 February 1885, Brière de l’Isle began his advance from Chu with a column of just under 7,200 troops, accompanied by 4,500 coolies. In ten days the column advanced to the outskirts of Langson. The troops were burdened with the weight of their provisions and equipment, and had to march through extremely difficult country. They also had to fight fierce actions to overrun stoutly-defended Chinese positions, at Tay-Hoa (4 February), Ha-Hoa (5 February) and Dong-Song (6 February). After a brief pause for breath at Dong-Song, the expeditionary corps pressed on towards Langson, fighting further actions at Deo-Quao (9 February), and Pho-Vy (11 February). On 12 February, in a costly but successful battle, the Turcos and marine infantry of Colonel Laurent Giovanninelli’s 1st Brigade stormed the main Chinese defences at Bac-Vie, several kilometres to the south of Langson. On 13 February the French column entered Langson, which the Chinese abandoned after fighting a token rearguard action at the nearby village of Ky-Lua.

Siege and Relief of Tuyen-Quan

The capture of Langson allowed substantial French forces to be diverted further west to relieve the small and isolated French garrison in Tuyen-Quan, which had been placed under siege in December 1884 by Liu Yongfu’s Black Flag Army and Tang Jingsong’s Yunnan Army. The Chinese and Black Flags sapped methodically up to the French positions, and in January and February 1885 breached the outer defences with mines and delivered seven separate assaults on the breach. The Tuyen-Quan garrison, 400 legionnaires and 200 Tonkinese auxiliaries under the command of chef de bataillon Marc-Edouard Dominé, beat off all attempts to storm their positions, but lost over a third of their strength (50 dead and 224 wounded) sustaining a heroic defence against overwhelming odds. By mid-February it was clear that Tuyen-Quan would fall unless it was relieved immediately.

General Brière de l’Isle personally led Giovanninelli's 1st Brigade back to Hanoi, and then upriver to the relief of Tuyen-Quan. The brigade, reinforced at Phu-Doan on 24 February by a small column from Hung-Hoa under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel de Maussion, found the route to Tuyen-Quan blocked by a strong Chinese defensive position at Hoa-Moc. On 2 March 1885 Giovanninelli attacked the left flank of the Chinese defensive line. The engagement at Hoa-Moc was the largest and most fiercely-fought action of the war. Two French assaults were decisively repulsed, and although the French eventually stormed the Chinese positions, they suffered very high casualties (76 dead and 408 wounded). Nevertheless, their costly victory cleared the way to Tuyen-Quan. The Yunnan Army and the Black Flags raised the siege and drew off to the west, and the relieving force entered the beleaguered post on 3 March. Brière de l’Isle praised the courage of the hard-pressed garrison in a widely-quoted order of the day. ‘Today, you enjoy the admiration of the men who have relieved you at such heavy cost. Tomorrow, all France will applaud you!’

The Endgame

Bang-Bo, Ky-Lua and the Retreat from Langson

Meanwhile General de Négrier, left at Langson with the 2nd Brigade, was encouraged by the French government to press on towards the Chinese border, in the belief that a threat to Chinese territory would force China to sue for peace. De Négrier defeated the Guangxi Army at Dong-Dang on 23 February and cleared it from Tonkinese territory. For good measure, the French crossed briefly into Guangxi province and blew up the 'Gate of China', an elaborate Chinese customs building on the Tonkin-Guanxi border. However, the French were not strong enough to exploit this victory.

On 23 and 24 March the 2nd Brigade, only 1,500 men strong, fought a fierce action with over 25,000 troops of the Guangxi Army entrenched near Zhennanguan on the Chinese border. This engagement, known as the Battle of Zhennan Pass in China, is normally called Bang-Bo in European sources, after the name of a village in the centre of the Chinese position where the fighting was fiercest. The French took a number of outworks on 23 March, but failed to take the main Chinese positions on 24 March and were fiercely counterattacked in their turn. Although the French made a fighting withdrawal and prevented the Chinese from piercing their line, casualties in the 2nd Brigade were relatively heavy (70 dead and 188 wounded) and there were ominous scenes of disorder as the defeated French regrouped after the battle. As the brigade's morale was precarious and ammunition was running short, de Négrier decided to fall back to Langson. The Chinese pursued him, and on 28 March de Négrier fought a battle at Ky-Lua in defence of Langson. Rested, recovered and fighting behind breastworks, the French successfully held their positions and inflicted crippling casualties on the Guangxi Army, avenging the defeat at Bang-Bo. But towards the end of the battle de Négrier was seriously wounded in the chest while scouting the Chinese positions. He was forced to hand over command to his senior regimental commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Paul-Gustave Herbinger. Herbinger was a noted military theoretician who had won a respectable battlefield reputation during the Franco-Prussian War, but was quite out of his depth as a field commander in Tonkin. Several French officers had already commented scathingly on his performance during the Langson campaign.

Upon assuming command of the brigade, Herbinger panicked. Despite the evidence that the Chinese had been decisively defeated and were streaming back in disarray towards the Chinese frontier, he convinced himself that they were preparing to encircle Langson and cut his supply line. Disregarding the appalled protests of some of his officers, he ordered the 2nd Brigade to abandon Langson on the evening of 28 March and retreat to Chu. The French retreat was conducted without loss and without interference from the Chinese, but Herbinger set an unnecessarily punishing pace and insisted on abandoning considerable quantities of food, ammunition and equipment. When the 2nd Brigade eventually rallied at Chu, its soldiers were exhausted and demoralised. Meanwhile the Chinese general Pan Dingxin, informed by his spies that the French were in full retreat, promptly turned his battered army around and reoccupied Langson on 30 March. The Chinese were in no condition to pursue the French to Chu, and contented themselves with a limited advance to Dong-Song.

There was also bad news for the French from the western front. The Black Flag and Yunnan Armies, still smarting from their defeat at Hoa-Moc, surprised and routed a French zouave battalion at Thanh-May on 23 March.

Collapse of Ferry's Government

Neither reverse was serious, but in the light of Herbinger's alarming reports Brière de l’Isle believed the situation to be much worse than it was, and sent an extremely pessimistic telegram back to Paris on the evening of 28 March. The political effect of this telegram was momentous. Ferry’s immediate reaction was to reinforce the army in Tonkin, and indeed Brière de l’Isle quickly revised his estimate of the situation and advised the government that the front could soon be stabilised. However, his second thoughts came too late. When his first telegram was made public in Paris there was an uproar in the Chamber of Deputies. A motion of no confidence was tabled, and Ferry’s government fell on 30 March. Ferry would never again become premier, and his political influence during the rest of his career would be severely limited. His successor, Charles de Freycinet, promptly concluded peace with China. The Chinese government agreed to implement the Tientsin Accord (implicitly recognising the French protectorate over Tonkin), and the French government dropped its demand for an indemnity for the Bac-Le Ambush. A peace protocol ending hostilities was signed on 4 April, and a substantive peace treaty was signed on 9 June by Li Hongzhang and the French minister Jules Patenôtre. An important factor in China's decision to make peace was fear of Japanese expansionism. Japan had taken advantage of China's distraction to intrigue in Korea, and the Qing court considered that the Japanese were a greater threat to China than the French.

Final Victories in Formosa

Ironically, while the war was being decided on the battlefields of Tonkin and in Paris, the Formosa expeditionary corps won two spectacular victories in March 1885. In a series of actions fought between 4 and 7 March Colonel Duchesne broke the Chinese encirclement of Jilong with a flank attack delivered against the east of the Chinese line, capturing the key position of La Table and forcing the Chinese to withdraw behind the Jilong River. Duchesne's victory sparked a brief panic in Taipei, but the French were not strong enough to advance beyond their bridgehead. The war in northern Formosa now reached a point of equilibrium. The French were holding a virtually impregnable defensible perimeter around Jilong but could not exploit their success, while Liu Mingchuan's army remained in presence just beyond their advanced positions. However, the French had one card left to play. Duchesne's victory enabled Admiral Courbet to detach a marine infantry battalion from the Jilong garrison to capture the Pescadores Islands in late March. Strategically, this was an important victory, which would have prevented the Chinese from further reinforcing their army in Formosa, but it came too late to affect the outcome of the war. Future French operations were cancelled on the news of Herbinger’s retreat from Langson on 28 March, and Courbet was on the point of evacuating Jilong to reinforce the Tonkin expeditionary corps, leaving only a minimum garrison at Magong in the Pescadores, when hostilities were ended in April by the conclusion of preliminaries of peace.

The French continued to occupy Jilong and the Pescadores until the conclusion of a definitive peace treaty on 9 June 1885. Admiral Courbet fell seriously ill during this occupation, and on 11 June died aboard his flagship Bayard in Magong harbour.

Aftermath

The peace treaty of June 1885 gave the French most of what they wanted. They were obliged to evacuate Formosa and the Pescadores (which Courbet had wanted to retain as a French counterweight to the British colony of Hong Kong), but the Chinese duly withdrew their troops from Tonkin, abandoning Liu Yongfu's Black Flag Army. The French rapidly occupied northern Tonkin and drove the Black Flags from their stronghold of Laokay on the Yunnan-Tonkin border. In the years that followed they crushed a vigorous Annamese resistance movement and consolidated their hold on Annam and Tonkin. Ultimately Cochin China, Annam and Tonkin (the territories which comprise the modern state of Vietnam) were incorporated with Laos and Cambodia into the French colony of Indochina.

As far as China was concerned, the war was a significant step in the decline of the Qing empire. The loss of the Fujian fleet on 23 August 1884 was considered particularly humiliating. The Chinese strategy also demonstrated the flaws in the late Qing national defence system of independent regional armies and fleets. The military and naval commanders in the south received no assistance from Li Hongzhang's Northern Seas (Beiyang) fleet, based in the Gulf of Petchili, and only token assistance from the Southern Seas (Nanyang) fleet at Shanghai. The excuse given, that these forces were needed to deter a Japanese penetration of Korea, was not convincing. The truth was, that having built up a respectable steam navy at considerable expense, the Chinese were reluctant to hazard it in battle, even though concentrating their forces would have given them the best chance of challenging France's local naval superiority. The empress dowager and her advisers responded in October 1885 by establishing a Navy Yamen on the model of the admiralties of the European powers, to provide unified direction of naval policy. The benefits of this reform were largely nullified by corruption, and although China acquired a number of modern ships in the decade after the Sino-French War the Chinese navies remained handicapped by incompetent leadership. The bulk of China's steamship fleet was destroyed or captured in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), and for decades thereafter China ceased to be a naval power of any importance.

See also

Notes

- ^ Technically the Army of the Two Guangs (Guangdong and Guangxi), but invariably called the Guangxi Army in French and other European sources.

References

- Elleman, Bruce A., Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795–1989 (New York, 2001) [1]

- Garnot, L'expédition française de Formose, 1884–1885 (Paris, 1894)

- Lecomte, Guet-apens de Bac-Lé (Paris, 1890)

- Lecomte, Lang-Son: combats, retraite et négociations (Paris, 1895)

- Loir, Maurice, L'escadre de l'amiral Courbet (Paris, 1886)

- Marolles, Vice-amiral de, La dernière campagne du Commandant Henri Rivière (Paris, 1932)

- Thomazi, A., La conquête de l'Indochine (Paris, 1934)