Kosovo

Template:Redirect4 Template:Redirect6

Kosovo | |

|---|---|

Map of Kosovo | |

| Capital | Pristina (also Prishtina, Priština) |

| Ethnic groups (2007) | 92% Albanians 5.3% Serbs 2.7% others [1] |

| Area | |

• Total | 10,908 km2 (4,212 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | n/a |

| Population | |

• 2007 estimate | 2,100,000[2] |

• 1991 census | 1,956,1961 |

• Density | 220/km2 (569.8/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2007 estimate |

• Total | $4 billion[3] (N/A) |

• Per capita | $1,800[3] (151st) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2007 estimate |

• Total | $3.237 billion[3] (N/A) |

• Per capita | $1,500[3] (119th) |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Calling code | 3812 |

| Internet TLD | None assigned |

Kosovo, UN protectorate | |

|---|---|

Kosovo within Serbia | |

| Capital | Pristina |

| Government | |

| Joachim Rücker | |

| Fatmir Sejdiu | |

| UN protectorate | |

| 10 June, 1999 | |

| May 2000 | |

• EULEX | 16 February, 2008 |

| Currency | Euro (EUR) |

| History of Kosovo |

|---|

|

Kosovo (Albanian: Kosova; Serbian: Косово и Метохија; [Kosovo i Metohija] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) is currently a disputed territory in the Balkans. The territory was a part of the lands of the Dardani tribes, then of the Roman, Byzantine, Bulgarian, Serbian, Ottoman empires. Later it was part of the Kingdom of Serbia, Italian Empire and of Yugoslavia. Following the 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia the territory came under the interim administration of the United Nations (UNMIK).

In February 2008, the Assembly of Kosovo declared Kosovo's independence as the Republic of Kosovo (Albanian: Republika e Kosovës). Its independence is recognized by some countries and opposed by others, including the Republic of Serbia, which continues to claim sovereignty over it as the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija (Serbian: Аутономна Покрајина Косово и Метохија / Autonomna Pokrajina Kosovo i Metohija).

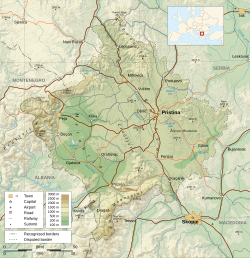

Kosovo borders Albania to the west, Central Serbia to the north and east, the Republic of Macedonia to the south, and Montenegro to the northwest. The largest city and the capital of Kosovo is Pristina (also Prishtina, Priština), while other cities include Peć (Peja), Prizren, and Mitrovica.

Name

Kosovo (Косово, Error using {{IPA symbol}}: "ˈkɔsɔvɔ" not found in list) is the Serbian possessive adjective of kos (кос) "blackbird",[4][5] an ellipsis for Kosovo Polje "field of the blackbirds", the site of the 1389 Battle of Kosovo Field. The name of the field was applied to an Ottoman province created in 1864.

The region currently known as "Kosovo" became an administrative region in 1946, as the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija. In 1974, the compositional "Kosovo and Metohija" was reduced to simple "Kosovo" in the name of the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, but in 1990 was renamed back to Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija.

The entire region is commonly referred to in English simply as Kosovo and in Albanian as Kosova. In Serbian, a distinction is made between the eastern and western areas; the term Kosovo (Косово) is used for the eastern part, while the western part is called "Metohija" (Метохија).

History

The formation of the Republic of Kosovo is a result of the turmoils of the disintegration of Yugoslavia, particularly the Kosovo War of 1996 to 1999, but it is suffused with issues dating back to the rise of nationalism in the Balkans under Ottoman rule in the 19th century, Albanian vs. Serbian nationalisms in particular, the latter notably surrounding the Battle of Kosovo eponymous of the Kosovo region.

Early history

During the Neolithic period, the region of Kosovo lay within the extent of the Vinča-Turdaş culture. In the 4th to 3rd centuries BC, it was the territory of the Thraco-Illyrian tribe of the Dardani, forming part of the kingdom of Illyria. Illyria was conquered by Rome in the 160s BC, and made the Roman province of Illyricum in 59 BC. The Kosovo region became part of Moesia Superior in AD 87. The Slavic migrations reached the Balkans in the 6th to 7th century. The area was absorbed into the Bulgarian Empire in the 850s, where Christianity and Slavic culture was cemented in the region. It was re-taken by the Byzantines after 1018. As the center of Slavic resistance to Constantinople in the region, it often switched between Serbian and Bulgarian rule on one hand and Byzantine on the other until the Serb principality of Rascia conquered it by the end of the 11th century. The Kosovo region became part of Moesia Superior in AD 87. The Slavic migrations reached the Balkans in the 6th to 7th century. Fully absorbed into the Serbian Kingdom until the end of the 12th, it became the secular and spiritual center of the Serbian medieval state of the Nemanyiden dynasty in the 13th century, with the Patriarchate of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Peć, while Prizren was the secular center. The zenith was reached with the formation of a Serbian Empire in 1346, which after 1371 transformed from a centralized absolutist medieval monarchy to a feudal realm. Kosovo became the hereditary land of the House of Branković and Vučitrn and Pristina flourished.

In the 1389 Battle of Kosovo, Ottoman forces defeated a coalition led by Lazar Hrebeljanović. In 1402, a Serbian Despotate was raised and Kosovo became its richest territory, famous for mines. The local House of Branković came to prominence as the local lords of Kosovo, under Vuk Branković, with the temporary fall of the Serbian Despotate in 1439. During the first fall of Serbia, Novo Brdo and Kosovo offered last resistance to the invading Ottomans in 1441; in 1455, it was finally and fully conquered by the Ottoman Empire.

Ottoman Kosovo (1455 to 1912)

Kosovo was part of the Ottoman Empire from 1455 to 1912, at first as part of the eyalet of Rumelia, and from 1864 as a separate province.

Kosovo was briefly taken by the Austrian forces during the Great War of 1683–1699 with help of 6,000 Albanian fighters led by Pjetër Bogdani. In 1690, the Serbian Patriarch of Peć Arsenije III led 37,000 predominantly Serbian families out of Kosovo. More migrations of Orthodox Christians from the Kosovo area continued throughout the 18th century. In 1766, the Ottomans abolished the Patriarchate of Peć and the position of Christians in Kosovo deteriorated, including full imposition of jizya (taxation of non-Muslims). In contrast, many Albanian chiefs converted to Islam and gained prominent positions in the Turkish regimen.[6] On the whole, "Albanians had little cause of unrest" and "if anything, grew important in Ottoman internal affairs."[7][citation needed] The final result of four and a half centuries of Muslim rule was a marked decline in the previously dominant Slavic Christian demographic element in Kosovo, replaced by a Turko-Albanian [8] stratum.

In the 19th century, there was a "awakening" of ethnic nationalism throughout the Balkans. The ethnic Albanian nationalism movement was centred in Kosovo.

In 1871, a Serbian meeting was held in Prizren at which the possible retaking and reintegration of Kosovo and the rest of "Old Serbia" was discussed, as the Principality of Serbia itself had already made plans for expansions towards Ottoman territory. In 1878, a Peace Accord was drawn that left the cities of Pristina and Kosovska Mitrovica under civil Serbian control, and outside Ottoman jurisdiction, while the rest of Kosovo remained under Ottoman control. As a response, ethnic Albanians formed the League of Prizren, pursuing political aspirations of unifying the Albanian people and seeking autonomy within the Ottoman Empire.

20th century

Balkan Wars to World War I

The Young Turk movement supported a centralist rule and opposed any sort of autonomy desired by Kosovars, and particularly the Albanians. In 1910, an Albanian uprising spread from Pristina and lasted until the Ottoman Sultan's visit to Kosovo in June of 1911. In 1912, during the Balkan Wars, most of Kosovo was captured by the Kingdom of Serbia, while the region of Metohija (Albanian: Dukagjini Valley) was taken by the Kingdom of Montenegro. An exodus of the local Albanian population occurred. This was described by Leon Trotsky, who was a reporter for the Pravda newspaper at the time. The Serbian authorities planned a re-colonization of Kosovo.[9] Numerous colonist Serb families moved into Kosovo, equalizing the demographic balance between Albanians and Serbs. Kosovo's status within Serbia was finalised the following year at the Treaty of London.[10]

In the winter of 1915-1916, during World War I, Kosovo saw a large exodus of the Serbian army which became known as the Great Serbian Retreat, as Kosovo was occupied by Bulgarians and Austro-Hungarians. In 1918, the Serbian Army pushed the Central Powers out of Kosovo. After World War I ended, the Monarchy was then transformed into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians on 1 December 1918.

Kingdom of Yugoslavia and World War II

The 1918–1929 period of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians witnessed a rise of the Serbian population in the region. Kosovo was split into four counties, three being a part of Serbia (Zvečan, Kosovo and southern Metohija) and one of Montenegro (northern Metohija). However, the new administration system since 26 April 1922 split Kosovo among three Areas of the Kingdom: Kosovo, Rascia and Zeta. In 1929, the Kingdom was transformed into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and the territories of Kosovo were reorganised among the Banate of Zeta, the Banate of Morava and the Banate of Vardar. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia lasted until the World War II Axis invasion of 1941, when the greatest part of Kosovo became a part of Italian-controlled Albania, and smaller bits by the Tsardom of Bulgaria and German-occupied Military Administration of Serbia. After numerous uprisings of Partisans led by Fadil Hoxha, Kosovo was liberated after 1944 with the help of the Albanian partisans of the Comintern, and became a province of Serbia within the Democratic Federal Yugoslavia.

Kosovo in Yugoslavia

The province was first formed in 1945 as the Autonomous Kosovo-Metohian Area to protect its regional Albanian majority within the People's Republic of Serbia as a member of the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia under the leadership of the former Partisan leader, Josip Broz Tito. After Yugoslavia's name change to the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Serbia's to the Socialist Republic of Serbia in 1953, Kosovo gained limited internal autonomy in the 1960s. In the 1974 constitution, the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo's government received more powers, including the highest governmental titles – President and Prime Minister and a seat in the Federal Presidency which made it a de facto Republic within the Federation, but remaining a Socialist Autonomous Province within the Socialist Republic of Serbia. (Similar rights were extended to Vojvodina). In Kosovo Serbo-Croatian, Albanian and Turkish were defined as official languages on the provincial level. Due to very high birth rates, the number of Albanians increased from 75% to over 90%. In contrast, the number of Serbs barely increased, and in fact dropped from 15% to 8% of the total population, since many Serbs departed from Kosovo as a response to the tight economic climate and increased incidents of alleged harassment from their Albanian neighbors. While there was tension, charges of "genocide" and planned harassments have been debunked as an excuse to revoke Kosovo's autonomy. For example in 1986 ""the Serbian Orthodox Church published an official, though false, claim that Kosovo Serbs were being subjected to an Albanian program of 'Genocide'. Even though they were disproven[2] by police statistics, the received wide play in the Serbian press and that lead to further ethnic problems and eventual removal of Kosovo's status. Beginning in March 1981, Kosovar Albanian students of the University of Prishtina organized protests seeking that Kosovo become a republic within Yugoslavia and human rights.[11] During the 1980s, ethnic tensions continued with frequent violent outbreaks against Yugoslav state authorities resulting in a further increase in emigration of Kosovo Serbs and other ethnic groups.[12][13] The Yugoslav leadership tried to suppress protests of Kosovo Serbs seeking protection from ethnic discrimination and violence.[14]

Disintegration of Yugoslavia and Kosovo War

Inter-ethnic tensions continued to worsen in Kosovo throughout the 1980s. The 1986 Memorandum of the Serbian Academy warned that Yugoslavia was suffering from ethnic strife and the disintegration of the Yugoslav economy into separate economic sectors and territories, which was transforming the federal state into a loose confederation.[15] On June 28 1989, Slobodan Milošević delivered the Gazimestan speech in front of a large number of Serb citizens at the main celebration marking the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Kosovo. Many think that this speech helped Milošević consolidate his authority in Serbia.[16] In 1989, Milošević, employing a mix of intimidation and political maneuvering, drastically reduced Kosovo's special autonomous status within Serbia and started cultural oppression of the ethnic Albanian population.[17] Kosovo Albanians responded with a non-violent separatist movement, employing widespread civil disobedience and creation of parallel structures in education, medical care, and taxation, with the ultimate goal of achieving the independence of Kosovo.[18] On July 2 1990, an unconstitutional Kosovo parliament declared Kosovo an independent country, the Republic of Kosova. In May 1992, Ibrahim Rugova was elected president[19]. During its lifetime, the Republic of Kosova was only recognized by Albania; it was formally disbanded in 2000 when its institutions were replaced by the Joint Interim Administrative Structure established by the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK).

Only after the Bosnian War, drawing considerable international attention, was ended with the Dayton Agreement in 1995, but the situation in Kosovo remained largely unaddressed by the international community, the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), an ethnic Albanian guerrilla group, by 1996 had started offering armed resistance to Serbian and Yugoslav security forces, resulting in early stages of the Kosovo War.[17][20] By 1998, as the violence had worsened and displaced scores of Albanians, Western interest had increased. The Serbian authorities were compelled to sign a ceasefire and partial retreat, monitored by OSCE observers according to an agreement negotiated by Richard Holbrooke. However, the ceasefire did not hold and fighting resumed in December 1998. The Račak massacre in January 1999 in particular brought new international attention to the conflict.[17] Within weeks, a multilateral international conference was convened and by March had prepared a draft agreement known as the Rambouillet Accords, calling for restoration of Kosovo's autonomy and deployment of NATO peacekeeping forces. The Serbian party found the terms unacceptable and refused to sign the draft.

NATO intervention between March 24 and June 10 1999[21], aimed to force Milošević to withdraw his forces from Kosovo, combined with continued skirmishes between Albanian guerrillas and Yugoslav forces resulted in a further massive displacement of population in Kosovo.[22] During the conflict, roughly a million ethnic Albanians fled or were forcefully driven from Kosovo. Altogether, more than 11,000 deaths have been reported to Carla Del Ponte by her prosecutors.[23] Some 3,000 people are still missing, of which 2,500 are Albanian, 400 Serbs and 100 Roma.[24] Ultimately by June Milošević had agreed to a foreign military presence within Kosovo and withdrawal of his troops.

The UN administration period

On June 10, 1999, the UN Security Council passed UN Security Council Resolution 1244, which placed Kosovo under transitional UN administration (UNMIK) and authorized KFOR, a NATO-led peacekeeping force. Resolution 1244 provided that Kosovo would have autonomy within the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and affirmed the territorial integrity of Yugoslavia, which has been legally succeeded by the Republic of Serbia.[25]

Some 200,000-280,000, representing the majority of the Serb population, left when the Serbian forces left. There was also some looting of Serb properties and even violence against some of those Serbs and Roma who remained.[26] The current number of internally displaced persons is disputed,[27][28][29][30] with estimates ranging from 65,000[31] to 250,000.[32][33][34] Many displaced Serbs are afraid to return to their homes, even with UNMIK protection. Around 120,000-150,000 Serbs remain in Kosovo, but are subject to ongoing harassment and discrimination.

Kosovo's political borders don't coincide with ethnic boundaries, and in 2001 an ethnic insurgency surfaced in the neighboring areas with ethnic Albanian majority, Preševo Valley in Central Serbia and the Polog Valley in the Republic of Macedonia, but eased within several months.

In 2001, UNMIK promulgated a Constitutional Framework for Kosovo that established the Provisional Institutions of Self-Government (PISG), including an elected Kosovo Assembly, Presidency and office of Prime Minister. Kosovo held its first free, Kosovo-wide elections in late 2001 (municipal elections had been held the previous year).

In March 2004, Kosovo experienced its worst inter-ethnic violence since the Kosovo War. The unrest in 2004 was sparked by a series of minor events that soon cascaded into large-scale riots.[35]

International negotiations began in 2006 to determine the final status of Kosovo, as envisaged under UN Security Council Resolution 1244. The UN-backed talks, lead by UN Special Envoy Martti Ahtisaari, began in February 2006. Whilst progress was made on technical matters, both parties remained diametrically opposed on the question of status itself.[36]

In February 2007, Ahtisaari delivered a draft status settlement proposal to leaders in Belgrade and Pristina, the basis for a draft UN Security Council Resolution which proposes 'supervised independence' for the province. A draft resolution, backed by the United States, the United Kingdom and other European members of the Security Council, was presented and rewritten four times to try to accommodate Russian concerns that such a resolution would undermine the principle of state sovereignty.[37] Russia, which holds a veto in the Security Council as one of five permanent members, had stated that it would not support any resolution which was not acceptable to both Belgrade and Kosovo Albanians.[38] Whilst most observers had, at the beginning of the talks, anticipated independence as the most likely outcome, others have suggested that a rapid resolution might not be preferable.[39]

After many weeks of discussions at the UN, the United States, United Kingdom and other European members of the Security Council formally 'discarded' a draft resolution backing Ahtisaari's proposal on 20 July 2007, having failed to secure Russian backing. Beginning in August, a "Troika" consisting of negotiators from the European Union (Wolfgang Ischinger), the United States (Frank Wisner) and Russia (Alexander Botsan-Kharchenko) launched a new effort to reach a status outcome acceptable to both Belgrade and Pristina. Despite Russian disapproval, the U.S., the United Kingdom, and France appeared likely to recognize Kosovar independence.[40] A declaration of independence by Kosovar Albanian leaders was postponed until the end of the Serbian presidential elections (4 February 2008). Most EU members and the US had feared that a premature declaration could boost support in Serbia for the ultra-nationalist candidate, Tomislav Nikolić.[41]

2008 declaration of independence

The Kosovar Assembly approved a declaration of independence on 17 February 2008.[42] Over the following days, several states (the United States, Turkey, Albania, Austria, Germany, Italy, France, the United Kingdom, Republic of China (Taiwan),[43] Australia and others) announced their recognition, despite protests by Serbia in the UN Security Council.[44]

The UN Security Council remains divided on the question (as of 25 February 2008). Of the five members with veto power, USA, UK, and France recognized the declaration of independence, and Russia and the People's Republic of China consider it illegal. As of 28 March 2008, no member-country of CIS, CSTO or SCO has recognized Kosovo as independent.[citation needed]

The European Union has no official position towards Kosovo's status, but has decided to deploy the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo to ensure a continuation of international civil presence in Kosovo. As of today, most of member-countries of NATO, EU, WEU and OECD have recognized Kosovo as independent.[citation needed]

Of Kosovo's immediate neighbour states, only Albania recognizes the declaration of independence. Croatia, Bulgaria and Hungary, all neighbours of Serbia, announced in a joint statement that they recognise the declaration.[45]

Geography

Kosovo has an area of 10,908 square kilometers[46] and a population of about 2.2 million. The largest cities are Pristina, the capital, with an estimated 170,000 inhabitants, Prizren in the south west with a population of 110,000, Peć in the west with 70,000, and Kosovska Mitrovica in the north with 70,000. The climate is continental, with warm summers and cold and snowy winters. Most of Kosovo's terrain in mountainous, the highest peak is Đeravica/Gjeravica (2656 m). There are two main plain regions, the Metohija basin is located in the western part of the Kosovo, and the Plain of Kosovo occupies the eastern part. The main rivers of the region are the White Drin, running towards the Adriatic Sea, with the Erenik among its tributaries), the Sitnica, the South Morava in the Goljak area, and Ibar in the north. The biggest lakes are Gazivoda, Radonjić, Batlava and Badovac.

Phytogeographically, Kosovo belongs to the Illyrian province of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the WWF and Digital Map of European Ecological Regions by the European Environment Agency, the territory of Kosovo belongs to the ecoregion of Balkan mixed forests.

39.1% of Kosovo is forested, about 52% is classified as agricultural land, 31% of which is covered by pastures and 69% is arable.[47]

Currently the 39,000 ha Sharr Mountain National Park, established in 1986 in the Šar Mountains along the border with the Republic of Macedonia, is the only national park in Kosovo, although the Bjeshkët e Nemuna National Park in the Albanian Alps along the border with Montenegro has been proposed as another one.[48]

Governance and constitutional status

Kosovo is under de facto governance of the Republic of Kosovo except for North Kosovo, which remains under de facto governance of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo continues to operate with the Provisional Institutions of Self-Government elected in 2007, and the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo which operates police, justice and civil administration. Serbian provincial elections are pending for 11 May 2008.

Autonomous Province under UN administration

In 1999, UN Security Council Resolution 1244 placed Kosovo under transitional UN administration pending a determination of Kosovo's future status. This Resolution entrusted the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) with sweeping powers to govern Kosovo, but also directed UNMIK to establish interim institutions of self-governance. Resolution 1244 permits Serbia no official role in governing Kosovo and since 1999 Serbian laws and institutions have not been valid in Kosovo. NATO has a separate mandate to provide for a safe and secure environment.

In May 2001, UNMIK promulgated the Constitutional Framework, which established Kosovo's Provisional Institutions of Self-Government (PISG). The PISG replaced the Joint Interim Administrative Structure (JIAS) established a year earlier. Since 2001, UNMIK has been gradually transferring increased governing competencies to the PISG, while reserving some powers that are normally carried out by sovereign states, such as foreign affairs. Kosovo has also established municipal government and an internationally-supervised Kosovo Police Service.

According to the Constitutional Framework, Kosovo shall have a 120-member Kosovo Assembly. The Assembly includes twenty reserved seats: ten for Kosovo Serbs and ten for non-Serb minorities (Bosniaks, Roma, etc). The Kosovo Assembly is responsible for electing a President and Prime Minister of Kosovo.

However, since 1999, the Serb-inhabited areas of Kosovo, such as North Kosovo have remained de facto independent from the Albanian-dominated government in Priština. They continue to uses Serbian national symbols and participate in Serbian national elections, which are boycotted in the rest of Kosovo. Serb-inhabited regions also boycott Kosovo elections. The municipalities of Leposavić, Zvečan and Zubin Potok are run by local Serbs, while the Kosovska Mitrovica municipality had rival Serb and Albanian governments until a compromise was agreed in November 2002.[citation needed]

In February 2003, the Serb areas united to form the Union of Serbian Districts and District Units of Kosovo and Metohija in a meeting in Kosovska Mitrovica, which has since served as the de facto "capital." The Union's President is Dragan Velić. There is also a central governing body, the Serbian National Council for Kosovo and Metohija (SNV). The President of SNV in North Kosovo is Dr Milan Ivanović, while the head of its Executive Council is Rada Trajković.

Local politics in the Serb areas are dominated by the Serbian List for Kosovo and Metohija. The Serbian List is led by Oliver Ivanović, an engineer from Kosovska Mitrovica.

In February of 2007 the Union of Serbian Districts and District Units of Kosovo and Metohija transformed into the Serbian Assembly of Kosovo and Metohija, presided by Marko Jakšić. The Assembly has strongly criticized the secessionist movements of the Albanian-dominated PISG Assembly of Kosovo. It has demanded unity of the Serb people in Kosovo, boycotted EULEX, and announced massive protests in support of Serbia's sovereignty over Kosovo. On 18 February 2008, day after Kosovo's unilateral declaration of independence, the Assembly declared it "null and void".

Within Serbia, Kosovo is the concern of the Ministry for Kosovo and Metohija, currently led by Slobodan Samardzic.

Republic of Kosovo

A new constitution for Republic of Kosovo has been approved by the Parliament of the Republic of Kosovo and is planned to come into force in June 2008.[49]

Foreign relations

There are currently eight countries maintaining embassies to the Republic of Kosovo: Albania,[50] Austria,[51] Germany,[52] the United Kingdom, [53] the United States,[54] Switzerland (also representing Liechtenstein),[55] and Italy.[56] As of June 2008, 42 countries recognize Kosovo as independent. Skënder Hyseni is Foreign Minister of the Republic of Kosovo. [57]

Military

The military of Kosovo is still in the process of being organized following the partially recognized declaration of independence of February 17 2008. Following the Kosovo War in 1999, United Nations Security Council Resolution 1244 placed Kosovo under the authority of the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK), with security provided by the NATO-led Kosovo Force (KFOR).[58]

Rule of law

Following the Kosovo War, due to many weapons in hands of civilians, law enforcement inefficiencies and widespread devastation, there was a tremendous surge in revenge killings and ethnic violence. The number of reported murders rose from 136 in 2000 to 245 in 2001. The number of reported arsons rose from 218 to 523 in the same period. UNMIK points out that the rise in reported incidents may correspond to an increased confidence in the police force rather than more crime. The number of noted serious crimes saw an increase between 1999 and 2000, since then it has been "starting to resemble the same patterns of other European cities."[59] [60] According to Amnesty International, the aftermath of the war resulted in an increase in the trafficking of women for sexual exploitation.[61][62][63] Organized crime continues to be a significant problem. However, there has been tremendous improvement in police action and by 2008, "murder rates in Kosovo have been in steady decline, dropping by 75 percent since 2003 with the current recorded rate today under three per 100,000 people" [3] a rate comparable to that of Switzerland[4], Ireland or Finland[5]. The landmines laid by both the Serbs and KLA during the Kosovo War and unexploded NATO ordnance remain a problem.[64]

Politics

The largest political party in Kosovo, the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), has its origins in the 1990s non-violent resistance movement to Miloševic's rule. The party was led by Ibrahim Rugova until his death in 2006.[65] The two next largest parties have their roots in the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA): the Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK) led by former KLA leader Hashim Thaci and the Alliance for the Future of Kosovo (AAK) led by former KLA commander Ramush Haradinaj.[66] Kosovo publisher Veton Surroi formed his own political party in 2004 named "Ora." Kosovo Serbs formed the Serb List for Kosovo and Metohija (SLKM) in 2004, but have boycotted Kosovo's institutions and never taken their seats in the Kosovo Assembly.[67]

In November 2001, the OSCE supervised the first elections for the Kosovo Assembly.[68] After that election, Kosovo's political parties formed an all-party unity coalition and elected Ibrahim Rugova as President and Bajram Rexhepi (PDK) as Prime Minister.[69] After Kosovo-wide elections in October 2004, the LDK and AAK formed a new governing coalition that did not include PDK and Ora. This coalition agreement resulted in Ramush Haradinaj (AAK) becoming Prime Minister, while Ibrahim Rugova retained the position of President. PDK and Ora were critical of the coalition agreement and have since frequently accused the current government of corruption.[citation needed]

Ramush Haradinaj resigned the post of Prime Minister after he was indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in March 2005. He was replaced by Bajram Kosumi (AAK).[70] But in a political shake-up after the death of President Rugova in January 2006, Kosumi himself was replaced by former Kosovo Protection Corps commander Agim Çeku.[71] Çeku has won recognition for his outreach to minorities, but Serbia has been critical of his wartime past as military leader of the KLA and claims he is still not doing enough for Kosovo Serbs. The Kosovo Assembly elected Fatmir Sejdiu, a former LDK parliamentarian, president after Rugova's death. Slaviša Petkovic, Minister for Communities and Returns, was previously the only ethnic Serb in the government, but resigned in November 2006 amid allegations that he misused ministry funds.[72][73] Today three of the total sixteen ministries in Government of the Republic of Kosovo have ministers from the minorities. Minister of Community and Return and Minister of Labour and Social Welfare are ethnic Serbs, while Minister of Environment and Spatial Planning is from Kosovo’s small Turkish minority. [74]

Parliamentary elections were held on 17 November 2007. After early results, Hashim Thaçi who was on course to gain 35 per cent of the vote, claimed victory for PDK, the Albanian Democratic Party, and stated his intention to declare independence. Thaçi has since formed a coalition with current President Fatmir Sejdiu's Democratic League which was in second place with 22 percent of the vote.[75] The turnout at the election was particularly low with most Serbs refusing to vote.[76]

Economy

Kosovo has one of the most under-developed economies in Europe, with a per capita income estimated at €1,565 (2004).[77] Despite substantial development subsidies from all Yugoslav republics, Kosovo was the poorest province of Yugoslavia.[78] Additionally, over the course of the 1990s a blend of poor economic policies, international sanctions, poor external commerce and ethnic conflict severely damaged the economy.[79]

Kosovo's economy remains weak. After a jump in 2000 and 2001, growth in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was negative in 2002 and 2003 and is expected to be around 3 percent 2004-2005, with domestic sources of growth unable to compensate for the declining foreign assistance. Inflation is low, while the budget posted a deficit for the first time in 2004. Kosovo has high external deficits. In 2004, the deficit of the balance of goods and services was close to 70 percent of GDP. Remittances from Kosovars living abroad accounts for an estimated 13 percent of GDP, and foreign assistance for around 34 percent of GDP.

Most economic development since 1999 has taken place in the trade, retail and the construction sectors. The private sector that has emerged since 1999 is mainly small-scale. The industrial sector remains weak and the electric power supply remains unreliable, acting as a key constraint. Unemployment remains pervasive, at around 40-50% of the labor force.[80]

UNMIK introduced an external trade regime and customs administration on September 3, 1999 when it set customs border controls in Kosovo. All goods imported in Kosovo face a flat 10% customs duty fee.[81] These taxes are collected from all Tax Collection Points installed at the borders of Kosovo, including those between Kosovo and Serbia.[82] UNMIK and Kosovo institutions have signed Free Trade Agreements with Croatia,[83] Bosnia and Herzegovina,[84] Albania and Republic of Macedonia.[81]

The euro is the official currency of Kosovo and used by UNMIK and the government bodies.[85] The Serbian dinar is used in the Serbian-populated parts. [citation needed]

The chief means of entry to this landlocked country, apart form the main highway leading to the south to Skopje, Republic of Macedonia, is Pristina International Airport.

Trade and investment

Kosovo's 2006 trade balance was total exports(FOB) $154mil and total imports(CIF) $1,612mil.

The Republic of Macedonia is Kosovo's largest import and export market (averaging €220 million and €9 million, respectively or 20% of whole Kosovo's trade), followed by Serbia (€111 million and €5 million app 12%), Germany (app 10% of total trade), China (app from 5-9% depending on season) and Turkey (app 6% of total imports). In total EU's 27 countries are Kosovo's biggest trade partner, 35% of all Kosovo's imports are coming from EU and app 50-60% of Kosovo's $150 million exports are going in EU27.[86]

The economy is hindered by Kosovo's still-unresolved international status, which has made it difficult to attract investment and loans.[87] The province's economic weakness has produced a thriving black economy in which smuggled petrol, cigarettes and cement are major commodities. The prevalence of official corruption and the pervasive influence of organised crime gangs has caused serious concern internationally. The United Nations has made the fight against corruption and organised crime a high priority, pledging a "zero tolerance" approach.

Kosovo has a reported foreign debt of 1,264 billion USD that is currently serviced by Serbia.

According to ECIKS from 2001 to 2004 Kosovo received $3,2 billion of foreign aid. International donnor conference is to be held in Switzerland in June or July 2008. Until now EU pledged 2 billion €, $350 mil by USA. Serbia also pledged 120 million € to Serb's enclaves in Kosovo.

Energy sector

At 14,700 Mt, Kosovo has the world’s fifth-largest proven reserves of lignite, a type of coal. The lignite is distributed across the Kosovo, Dukagjin and Drenica basins, although mining has so far been restricted to the Kosovo basin. Coal reserves are found in two main basins and are currently being mined in the coal mines of Bardh open-cast coal mine and Mirash open-cast coal mine.

Energy sector presents a major potential for development of Kosovo's economy. There are two large coal-fired electrical power plants named "Kosovo A" and "Kosovo B" and the project to build a larger 2100-MW coal-fired power plant is underway with expected completion in 2012.

Mining

Kosovo has lead-zinc-silver mines of Artana (Novo Brdo), Belo Brdo, Stan Terg and Hajvalia mines, and the Crnac mine. During the lead-zinc-silver exploitation at Farbani Potok (Artana-Novo Brdo), about 3 Mt of high-grade halloysite was discovered. Halloysite is an aluminosilicate clay mineral used as a raw material for porcelain and bone china. This is only one of five known exploitable deposits of this very high-value (US$140-450/t) clay, the other four being in New Zealand, Turkey, China and Utah, US. Current world production is estimated at 150,000 t/y. There is also nickel to be found in Kosovo and the largest working mine is in Çikatova (Dushkaja and Suke) and Gllavica (District of Uroševac). There are significant deposits of chromium, bauxite and magnesite, but mining has been stalled since 1999.

Unemployment

A major issue in Kosovo that is undermining Kosovo's development is unemployment. Official unemployment rate stands at 40%. The World Bank states that even with 6 per cent annual growth (twice what Kosovo manages at the moment), it would take ten years to cut unemployment by half, from 40 to 20 per cent. [citation needed] Persistent unemployment, in particular among the young, will fuel frustration, which would be bad for political peace.[6] The unemployment rate among young people age under 25, whom account of approximately 50% of Kosovo's population, is much higher, approximately 60%.[88] As such, a system of Kosovars going abroad as migrant workers has emerged. Approximately one out of five Kosovar households report having had a family member search for work abroad.[89] Kosovo has the youngest population in Europe [citation needed], so in coming years, with significant development of educational sector on Kosovo, the current unemployment situation could be improved. [citation needed]

Administrative regions

Kosovo, for administrative reasons, is considered as consisting of seven districts. North Kosovo maintains its own government, infrastructure and institutions by its dominant ethnic Serb population in the District of Kosovska Mitrovica, viz. in the Leposavić, Zvečan and Zubin Potok municipalities and the northern part of Kosovska Mitrovica.

Districts

Municipalities and cities

Kosovo is also divided into 30 municipalities:

Demographics

According to the Kosovo in Figures 2005 Survey of the Statistical Office of Kosovo,[90][91][92] Kosovo's total population is estimated between 1.9 and 2.2 million with the following ethnic composition: Albanians 92 %, Serbs 4%, Bosniaks and Gorans 2%, Turks 1%, Roma 1%.

Albanians, steadily increasing in number, have constituted a majority in Kosovo since the 19th century, the earlier ethnic composition being disputed. The native dialect of the Kosovar Albanian population is Gheg Albanian, although Standard Albanian is now widely used as an official language.[93][94] According to the draft Constitution of Kosovo, Serbian is another official language.[95] Kosovo's political boundaries don't coincide with ethnic boundaries; Serbs form a local majority in North Kosovo and several smaller enclaves, while there are large areas with Albanian majority outside Kosovo in the neighboring regions of former Yugoslavia, namely in the northwest of the Republic of Macedonia and in Preshevo Valley of Central Serbia.

Islam (mostly Sunni, with a Bektashi minority[19]) is the predominant religion in Kosovo, brought into the region with the Ottoman conquest in the 15th century and now nominally professed by most of the ethnic Albanians, by the Bosniak, Gorani, and Turkish communities, and by some of the Roma/Ashkali-"Egyptian" community. Islam, however, hasn't saturated the Kosovar society, which remains largely secular.[96] The Serb population, estimated at 100,000 to 120,000 persons, is largely Serbian Orthodox. Kosovo is densely covered by numerous Serb Orthodox churches and monasteries. About three percent of ethnic Albanians in Kosovo are Roman Catholic.[97][98][99] Some 80% of the former 150,000 members of the Roma and Ashkali minority were driven out of the country.[100]

At 1.3% per year, ethnic Albanians in Kosovo have the fastest rate of growth in population in Europe.[101] Over an 82-year period (1921-2003) the population grew to 460% of its original size. If growth continues at such a pace, the population will reach 4.5 million by 2050.[102]

By contrast, from 1948 to 1991, the Serb population of Kosovo increased by but twelve percent (one third the growth of the population in the rest of Serbia). The population of Albanians in Kosovo increased by three hundred percent in the same period -- a rate of growth twenty-five times that of the Serbs in Kosovo.

Society

Cinema and media

Although in Kosovo the music is diverse, authentic Albanian music (see World Music) and Serbian music do still exist. Albanian music is characterized by the use of the çiftelia (an authentic Albanian instrument), mandolin, mandola and percussion. Classical music is also well-known in Kosovo and has been taught at several music schools and universities (at the University of Prishtina Faculty of Arts in Priština and the University of Priština Faculty of Arts at Kosovska Mitrovica).

Sports

Several sports federations have been formed in Kosovo within the framework of Law No. 2003/24 "Law on Sport" passed by the Assembly of Kosovo in 2003. The law formally established a national Olympic Committee, regulated the establishment of sports federations and established guidelines for sports clubs. At present only some of the sports federations established have gained international recognition.

See also

- Assembly of Kosovo

- Government of Kosovo

- Prime Minister of Kosovo

- President of Kosovo

- Serbs in Kosovo

- Albanians in Kosovo

- Post and Telecom of Kosovo

- Albanian nationalism and independence

- Demographic history of Kosovo

- Unrest in Kosovo during March 2004

- Metohija

- North Kosovo

- Flag of Kosovo

- 2008 Kosovo declaration of independence

References

- ^ Enti i Statistikës së Kosovës

- ^ See: [1] UN estimate, Kosovo’s population estimates range from 1.9 to 2.4 million. The last two population census conducted in 1981 and 1991 estimated Kosovo’s population at 1.6 and 1.9 million respectively, but the 1991 census probably undercounted Albanians. The latest estimate in 2001 by OSCE puts the number at 2.4 Million. The World Factbook gives an estimate of 2,126,708 for the year 2007 (see "Kosovo". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.).

- ^ a b c d CIA - The World Factbook - Kosovo, updated on March 20 2008, accessed on April 5 2008.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ "The name Kosovo". Dr John-Peter Maher, Professor Emeritus of Linguistics, Northeastern Illinois University

- ^ The Balkans. From Constantinople to Communism. Dennis Hupchik

- ^ Hupchik

- ^ Kosovo.Catholic Encyclopaedia

- ^ Elsie, R. (ed.) (2002): "Gathering Clouds. The roots of ethnic cleansing in Kosovo. Early twentieth-century documents". Dukagjini Balkan Books, Peja (Kosovo, Serbia). ISBN 9951-05-016-6

- ^ Treaty of London, 1913

- ^ New York Times 1981-04-19, "One Storm has Passed but Others are Gathering in Yugoslavia"

- ^ Reuters 1986-05-27, "Kosovo Province Revives Yugoslavia's Ethnic Nightmare"

- ^ Christian Science Monitor 1986-07-28, "Tensions among ethnic groups in Yugoslavia begin to boil over"

- ^ New York Times 1987-06-27, "Belgrade Battles Kosovo Serbs"

- ^ SANU (1986): Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts Memorandum. GIP Kultura. Belgrade.

- ^ The Economist, June 05, 1999, U.S. Edition, 1041 words, "What's next for Slobodan Milošević?"

- ^ a b c Rogel, Carole. Kosovo: Where It All Began. International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, Vol. 17, No. 1 (September 2003): 167-182.

- ^ Clark, Howard. Civil Resistance in Kosovo. London: Pluto Press, 2000. ISBN 0745315690

- ^ a b Babuna, Aydın. Albanian national identity and Islam in the post-Communist era. Perceptions 8(3), September-November 2003: 43-69.

- ^ Rama, Shinasi A. The Serb-Albanian War, and the International Community’s Miscalculations. The International Journal of Albanian Studies, 1 (1998), pp. 15-19.

- ^ "Operation Allied Force". NATO.

- ^ Larry Minear, Ted van Baarda, Marc Sommers (2000). "NATO and Humanitarian Action in the Kosovo Crisis" (PDF). Brown University.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "World: Europe UN gives figure for Kosovo dead".

- ^ KiM Info-Service (07/06/00). "3,000 missing in Kosovo".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "RESOLUTION 1244 (1999)". BBC News. 1999-06-17. Retrieved 2008-02-19.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Kosovo: The Human Rights Situation and the Fate of Persons Displaced from Their Homes (.pdf) ", report by Alvaro Gil-Robles, Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Strasbourg, October 16 2002, p. 30.

- ^ UNHCR, Critical Appraisal of Responsee Mechanisms Operating in Kosovo for Minority Returns, Pristina, February 2004, p. 14.

- ^ U.S. Committee for Refugees (USCR), April 2000, Reversal of Fortune: Yugoslavia's Refugees Crisis Since the Ethnic Albanian Return to Kosovo, p. 2–3.

- ^ "Kosovo: The human rights situation and the fate of persons displaced from their homes (.pdf) ", report by Alvaro Gil-Robles, Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Strasbourg, October 16 2002.

- ^ International Relations and Security Network (ISN): Serbians return to Kosovo not impossible, says report (.pdf) , by Tim Judah, June 7 2004.

- ^ European Stability Initiative (ESI): The Lausanne Principle: Multiethnicity, Territory and the Future of Kosovo's Serbs (.pdf) , June 7 2004.

- ^ Coordinating Centre of Serbia for Kosovo-Metohija: Principles of the program for return of internally displaced persons from Kosovo and Metohija .

- ^ UNHCR: 2002 Annual Statistical Report: Serbia and Montenegro, pg. 9

- ^ U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants (USCRI): Country report: Serbia and Montenegro 2006.

- ^ U.S State Department Report, published in 2007.

- ^ "UN frustrated by Kosovo deadlock ", BBC News, October 9 2006.

- ^ Southeast European Times (29/06/2007). "Russia reportedly rejects fourth draft resolution on Kosovo status".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Southeast European Times (09/07/07). "UN Security Council remains divided on Kosovo".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ James Dancer (30/03/07). "A long reconciliation process is required". Financial Times.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Simon Tisdall (13/11/07). "Bosnian nightmare returns to haunt EU". The Guardian.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ BBC NEWS | Europe | Q&A: Kosovo's future

- ^ "Kosovo MPs proclaim independence", BBC News Online, 17 February 2008

- ^ Hsu, Jenny W (2008-02-20). "Taiwan officially recognizes Kosovo". Taipei Times. Retrieved 2008-05-13.

- ^ "Recognition for new Kosovo grows", BBC News Online, 18 February 2008

- ^ BBC News, Serbia's neighbours accept Kosovo , accessed 12:41 19 March 2008.

- ^ "Statistical Office of Kosovo".

- ^ Strategic Environmental Analysis of Kosovo. The Regional Environmental Center for Central and Eastern Europe, Prishtina, July 2000.

- ^ Kosovo: Biodiversity assessment. Final Report submitted to the USAID, ARD-BIOFOR IQC Consortium, May 2003.

- ^ Constitution of Kosovo - Official Website

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- ^ "Austrian representations - Kosovo". Austrian Foreign Ministry. Retrieved 2008-04-17.

- ^ Deutsche Botschaft Pristina - Startseite

- ^ British Office Pristina, Kosovo

- ^ Website of the US Embassy, Pristina 9 March 2008

- ^ swissinfo.ch 28 March 2008

- ^ "Italian Embassy in Pristina", qn.quotidiano.net, 19 March 2008. Link accessed 2008-04-26. Template:It icon

- ^ http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/main/news/8228

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_of_Kosovo Military of Kosovo

- ^ UNMIK statistics

- ^ Kosovo Crime Wave, 17 January 2001

- ^ Kosovo UN troops 'fuel sex trade', BBC.

- ^ Kosovo: Trafficked women and girls have human rights, Amnesty International.

- ^ Nato force 'feeds Kosovo sex trade', Guardian Unlimited.

- ^ Landmine Monitor: Kosovo. 2004.

- ^ "Kosovo Update: Main Political Parties ", European Forum, 18 March 2008

- ^ "Kosovo Update: Main Political Parties ", European Forum, 18 March 2008

- ^ "Kosovo Update: Main Political Parties ", European Forum, 18 March 2008

- ^ "OSCE Mission in Kosovo - Elections ", Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe

- ^ "Power-sharing deal reached in Kosovo ", BBC News, 21 February 2002

- ^ "Timeline: Kosovo ", BBC News, 11 April 2008

- ^ "Former Rebel set to lead Kosovo ", BBC News, 2 March 2006

- ^ "Kosovo: Serb minister resigns over misuse of funds ", Adnkronos international (AKI), November 27 2006

- ^ "Sole Kosovo Serb cabinet minister resigns: PM ", Agence France-Presse (AFP), November 24 2006.

- ^ http://www.ks-gov.net/pm/Ministritë/tabid/83/language/en-US/Default.aspx

- ^ "Kosovo gets pro-independence PM ", BBC News, 9 January 2008

- ^ EuroNews: Ex-guerrilla chief claims victory in Kosovo election. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- ^ The World Bank (2006). "Kosovo Brief 2006".

- ^ Christian Science Monitor 1982-01-15, "Why Turbulent Kosovo has Marble Sidewalks but Troubled Industries"

- ^ The World Bank (2006/2007). "World Bank Mission in Kosovo".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ eciks (04/05/06). "May finds Kosovo with 50% unemployed".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b U.S. Commercial Service. "Doing Business in Kosovo".

- ^ Economic Reconstruction and Development in South East Europe. "External Trade and Customs" (PDF).

- ^ B92 (02/10/06). "Croatia, Kosovo sign Interim Free Trade Agreement". mrt.com.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ EU in Kosovo (17/02/06). "UNMIK and Bosnia and Herzegovina Initial Free Trade Agreement" (PDF). UNMIK.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ EU in Kosovo. "Invest in Kosovo".

- ^ The World Bank (April 2006). "Kosovo Monthly Economic Briefing: Preparing for next winter" (PDF).

- ^ BBC News (03/05/05). "Brussels offers first Kosovo loan".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Kosovo Poverty Assessment ", World Banl, 3 October 2007

- ^ "Kosovo Poverty Assessment ", World Banl, 3 October 2007

- ^ UNMIK. "Kosovo in figures 2005" (PDF). Ministry of Public Services.

- ^ BBC News (23/12/05). "Muslims in Europe: Country guide".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ BBC News (20/11/07). "churchesRegions and territories: Kosovo".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Albanian, Gheg A language of Serbia and Montenegro. Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version.

- ^ Sylvia Moosmüller & Theodor Granser. The spread of Standard Albanian: An illustration based on an analysis of vowels. Language Variation and Change (2006), 18: 121-140.

- ^ Draft Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo

- ^ Kosovo touts 'Islam Lite'. The Associated Press, February 21, 2008.

- ^ International Crisis Group (31/01/01). "Religion in Kosovo".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ International Religious Freedom Report 2007 (U.S. Department of States) - Serbia (includes Kosovo)

- ^ International Religious Freedom Report 2006 (U.S. Department of States) - Serbia and Montenegro (includes Kosovo)

- ^ Society for Threatened Peoples

- ^ Albanian Population Growth

- ^ Kosovo-Hotels, Prishtina - Kosovo-Hotels, Prishtinë

Further reading

Malcolm, Noel (1999). Kosovo: A Short History. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0060977752.

External links

Wikimedia Atlas of Kosovo

Wikimedia Atlas of Kosovo- United Nations Interim Administration in Kosovo

- The Government of Kosovo and Prime minister's office

- Assembly of Kosovo

- President of Kosovo

- Serbian Government for Kosovo and Metohija

- "Kosovo". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency.

- Visit Kosovo - Tourism Website

- Template:Wikitravel