London, Ontario

42°59′14″N 81°14′47″W / 42.98714°N 81.246268°W

City of London | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname: "The Forest City" | |

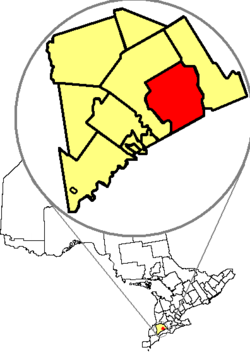

Location of London in relation to Middlesex County and the Province of Ontario | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Ontario |

| County | Middlesex County |

| Settled | 1826 as a village |

| Incorporated | 1855 as a city |

| Government | |

| • City Mayor | Anne Marie DeCicco-Best |

| • Governing Body | London City Council |

| • MPs | Sue Barnes (LPC) Glen Pearson (LPC) Irene Mathyssen (NDP) Joe Preston (CPC) |

| • MPPs | Chris Bentley (OLP) Deb Matthews (OLP) Steve Peters (OLP) Khalil Ramal (OLP) |

| Area | |

• City | 420.57 km2 (162.34 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 251 m (823 ft) |

| Population (2006)[1] | |

• City | 352,395 (Ranked 15th) |

| • Density | 837.9/km2 (2,170.2/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 457,720 (Ranked 10th) |

| source: Statistics Canada | |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Postal code span | N5V to N6P |

| Area code | (519/226) |

| Website | http://www.london.ca/ |

London is a city in Southwestern Ontario, Canada along the Quebec City-Windsor Corridor with a metropolitan area population of 457,720; the city proper had a population of 352,395 in the 2006 Canadian census.

London is the seat of Middlesex County, at the forks of the non-navigable Thames River, approximately halfway between Toronto, Ontario and Detroit, Michigan. London and the surrounding area (roughly, the territory between Kitchener-Waterloo and Windsor) is collectively known as Southwestern Ontario. The City of London is a single-tier municipality, politically separate from Middlesex County though it remains the official county seat.

London was first permanently settled by Europeans between 1801 and 1804 by Peter Hagerman [2] and became a village in 1826. Since then, London has grown into the largest Southwestern Ontario municipality and the city has developed a strong focus towards education, health care, tourism, manufacturing, economic leadership and prosperity.

History

Founding, original siting

Prior to European contact in the 18th century, the present site of London was occupied by several Neutral and Odawa/Ojibwa villages. A native village at the forks of Askunessippi, now called the "Thames River", was called Kotequogong by the latter two groups. Archaeological investigations in the region indicate that aboriginal people have resided in the area for at least the past 10,000 years.[3]

The current location of London was selected as the site of the future capital of Upper Canada in 1793 by Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe. Simcoe named the settlement after London, England and renamed the river. However, this choice of a capital site in the midst of extensive hardwood forests was initially rejected by Guy Carleton, (Governor Dorchester), with the comment that "access to London would be limited to hot-air balloons".[citation needed]

In 1814, there was a skirmish during the War of 1812 in what is now southwest London at Reservoir Hill, formerly Hungerford Hill.

The village of London was not founded for another third of a century after Simcoe's efforts, in 1826, and not as the capital he envisioned. Rather, it was administrative seat for a great area west of the actual capital, Toronto. More locally, it was part of the Talbot Settlement, named for Colonel Thomas Talbot, the chief coloniser of the area, who oversaw the land surveying and built the first government buildings for the administration of the Western Ontario peninsular region. Together with the rest of Southwestern Ontario that formed the settlement, the village benefited from Talbot's provisions, not only for building and maintaining roads, but also for assignment of access priorities to main routes to productive land, rather than to Crown and clergy reserves, which were receiving preference in the rest of Ontario.

In 1832, the new settlement suffered an outbreak of cholera. London proved a centre of strong Tory support during the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837, notwithstanding a brief rebellion led by Dr. Charles Duncombe, who was forced to flee to the U.S. Consequently, the British government located its Ontario peninsular garrison there in 1838, increasing its population with soldiers and their dependents, and the business support populations they required.

On April 13, 1845, fire destroyed much of London, which was at the time largely constructed of wooden buildings. One of the first casualties was the town's only fire engine. In the 1860s, a sulphur spring was discovered at the forks of the Thames River while industrialists were drilling for oil.[4] The springs became a popular destination for wealthy Ontarians, until the turn of the 20th century when a textile factory was built at the site, replacing the spa.

Nineteenth Century development

"Sir John Carling, the noted brewer and Tory MP for London, in an address in 1901, gave three turning-points to explain the rise of London; the location of the district court and administration in London in 1826; the stationing of the Imperial military garrison there in 1838; and the arrival of the railway in 1853. His analysis is quite correct."[5]

In 1875, London's first iron bridge, the Blackfriars Street Bridge, was constructed, replacing a succession of flood-failed wooden structures that had provided the city's only northern road crossing of the river. A rare example of a bowstring truss bridge, it remains open to vehicular traffic.[6] The Blackfriars, amidst the kilometer plus of river-distance between the Carling Brewery and the historic Tecumseh Park (and including a major mill), linked London with its western suburb of Petersville, named for Squire Peters of Grosvenor Lodge. That community joined with the southern subdivision of Kensington in 1874, formally incorporating as the municipality of Petersville. Although changing its name in 1880 to the more inclusive "London West", it remained a separate municipality until ratepayers voted for amalgamation with London in 1897, largely due to repeated flooding of the village, with its lower ground. The most serious flood was that of July 1883, which resulted in serious loss of life and property devaluation.[7] This area retains much original and attractively maintained 19th C tradespeople's and workers' housing, including Georgian cottages as well as larger houses, and a distinct sense of place. The renamed Labatt Park is a very well tended sports field beside a newly designed and landscaped promenade walk along the dike, overlooking Harris Park, constructed by the Upper Thames River Conservation Authority. London's eastern suburb, the aptly named London East, was (and remains) an industrial centre, which also incorporated in 1874. Attaining the status of town in 1881, it continued as a separate municipality until concerns over expensive waterworks and other fiscal problems led to amalgamation in 1885. The southern suburb of London was collectively known as "London South". It includes the distinctive Wortley Village. Never incorporated, South was annexed to the city in 1890. By contrast, the settlement at Broughdale on the city's north end had clear identity, adjoined the university, and was not annexed until 1961.

While other Protestant cities in Ontario (notably Toronto) remained under the sway of the Orange Order well into the 20th Century, London abandoned sectarianism in the 19th Century. In 1877, Catholic and Protestant Irish in London formed the Irish Benevolent Society, which was open to both Catholics and Protestants and forbade the discussion of Irish politics. The influence of the Orange Order (and of Catholic organizations) quickly waned. The Society survives to this day.

On May 24, 1881, the ferry SS Victoria capsized in the Thames River, drowning approximately 200 passengers, the worst disaster in London's history. Two years later, on July 12, 1883, the first of the two most devastating floods in London's history killed 17 people. The second major flood, of April 26, 1937, destroyed more than a thousand houses and caused millions of dollars in damages, particularly in West London. After repeated floods the Upper Thames River Conservation Authority in 1952 opened Fanshawe Dam on the North Thames, to control the downstream rivers. Financing for this project from the federal, provincial, and municipal governments. Other natural disasters include a 1984 tornado that led to damage on several streets in the White Oaks area of South London.

London's role as a military centre continued into the 20th Century during the two World Wars, serving as the administrative centre for the Western Ontario district. Today there is still an active Garrison Support Unit in the city at Wolseley Barracks.

Twentieth Century development

London annexed many of the surrounding communities in 1961, including Byron and Masonville, adding 60,000 people and more than doubling its area. After this amalgamation, suburban growth accelerated as London grew outward in all directions, creating expansive new subdivisions such as Westmount, Oakridge, Whitehills, Pond Mills and White Oaks.

In 1993, London annexed nearly the entire Town of Westminster, a large, primarily rural municipality directly south of the city, including the town of Lambeth, Middlesex County, Ontario. With this massive annexation, London almost doubled in area again, adding several thousand more residents. London now stretches south to the boundary with Elgin County.

The 1993 annexation made London one of the largest urban municipalities in Ontario. Intense commercial/residential development is presently occurring in the southwest and northwest areas of the city. Opponents of this development cite urban sprawl, destruction of rare Carolinian zone forest and farm lands, replacement of distinctive regions by generic malls, and standard transportation and pollution concerns as major issues facing London. The City of London is currently the tenth-largest city in Canada, Tenth-largest census metropolitan area in Canada, and the fourth-largest city in Ontario.

Law and government

London's municipal government is divided among fourteen councillors (one representing each of London's fourteen wards) and a Board of Control, consisting of four controllers and the mayor. London's current mayor is Anne Marie DeCicco-Best, re-elected in 2006.

Historically, the Board of Control was introduced during a period of expansion so the ward councillors could deal with ward issues while the board dealt with problems affecting the entire city. Although London has many ties to Middlesex County, it is now "separated" and the two have no jurisdictional overlap. Exception here is granted to the Middlesex County courthouse and former jail as the judiciary is administered directly by the province.

The composition of the City Council was challenged by two ballot questions during the civic election of 2003 on whether city council should be reduced in size and whether the Board of Control should be eliminated. Councillor Fred Tranquilli, Ward 3, was responsible for these ballot intiatives. He presented a re-designed form of local government entitled 'A Better Way', which was a refinement and modification of a similar proposal presented by the Urban League of London after the City's last annexation in 1996. Both would have seen the council reduced to ten wards and Board of Control eliminated. The council could not come to a determination and as a result decided to put two questions on the ballot for the fall 2003 election.

While the "yes" votes prevailed in both instances, the voter turnout failed to exceed 50 per cent and was therefore insufficient to make the decisions binding under the Municipal Act. When the council voted to retain the status quo Imagine London, a citizens group, petitioned the Ontario Municipal Board (OMB) to change the ward composition of the city from seven wards in a roughly radial pattern from the downtown core to 14 wards defined by communities of interest in the city which includes a separate ward for the core.

The OMB ruled for the petitioners in December, 2005 and while the city sought leave to appeal the OMB decision via the courts, leave was denied on February 28, 2006 in a decision of Superior Court's Justice McDermid.

In response, the city conceded to the governance change, but asked for special legislation from the province to ensure that there will only be one councillor in each of the 14 new wards, not two. On June 1, 2006 the Ontario bill received royal assent which guarantees that London will have one councillor per ward.

In the provincial government, London is represented by:

- Christopher Bentley (Liberal, London West)

- Deb Matthews (Liberal, London North Centre)

- Steve Peters (Liberal, Elgin-Middlesex-London)

- Khalil Ramal (Liberal, London-Fanshawe)

In the federal government, London is represented by:

- Sue Barnes (Liberal, London West)

- Glen Pearson (Liberal, London North Centre)

- Joe Preston (Conservative, Elgin-Middlesex-London)

- Irene Mathyssen (NDP, London Fanshawe)

See also: List of mayors of London, Ontario, Roman Catholic Bishops of London, Ontario

Civic initiatives

Special City of London initiatives in Old East London, such as the creation of the Old East Heritage Conservation District under Part V of the Ontario Heritage Act, special Building Code policies and Facade Restoration Programs, are helping to create a renewed sense of vigour in the East London Business District.[citation needed]

Historic buildings

London is home to over 100 heritage properties, registered at all levels of government.[8] A variety of architectural styles can be found in London, including:

Geography

The area was formed during the retreat of the glaciers during the last ice age, which produced areas of marshland, notably the Sifton Bog (which is actually a fen), as well as some of the most agriculturally productive areas of farmland in Ontario. The eastern half of the city is generally flat, with the exception being around the five neighboring ponds in the south, with gently rolling hills in the west and north.

The Thames River dominates London's geography, with the North Thames River and Thames River meeting at the centre of the city known as "The Forks" or "The Fork of the Thames." The North Thames runs through the man-made Fanshawe Lake, located in northeast London. Fanshawe Lake was created by Fanshawe Dam, which was constructed to protect the areas down river from catastrophic flooding which affected the city on two occasions in the past (1883 and 1937).

Climate

London has a humid continental climate. Because of its location in the continent and proximity to the Great Lakes, London experiences very contrasting seasons. The summers are usually warm to hot and humid (although slightly cooler than Toronto or Windsor), while the winters are normally quite cold but with frequent thaws. London has the most thunderstorms of any area in Canada[citation needed] due to the lake breeze convergence. For its southerly location within Canada, it does receive quite a lot of snow, averaging slightly over 200 cm (80 inches) per year. The majority of this is lake effect snow originating from Lake Huron, some 60 km (40 miles) to the northwest which occurs when strong, cold winds blow from that direction.

Major parks

- Victoria Park, in downtown London

- Labatt Memorial Park, in central London at the river forks

- Harris Park, in central London

- Gibbons Park, in north-central London

- Fanshawe Conservation Area, in northeast London

- Springbank Park, in Southwest London a.k.a. Byron

- Westminster Ponds, in south London

Economy and industry

London's economy is dominated by locomotive and military vehicle production, insurance, and information technology; the London Life insurance company was founded there, and Electro-Motive Diesels, Inc. (formerly General Motors' Electro-Motive Division) now builds all its locomotives in London. General Dynamics Land Systems also builds armoured personnel carriers there. London also is a source of life sciences and biotechnology related research; much of this is spurred on by the University of Western Ontario. The headquarters of the Canadian division of 3M are located in London and both the Labatt and Carling breweries were founded here. Kellogg's also has a major factory in London. Thanks to a $223 million expansion that started in 1984, Kellogg Canada's 106,000 m² London plant is one of the most technologically advanced cereal manufacturing facilities within the Kellogg Company. A portion of the population of the city work in factories outside of the city limits, including Ford and the joint General Motors Suzuki automotive plant CAMI, with further potential in a future Toyota plant in Woodstock. In 1999 the Western Fair Association introduced slot machines. Currently, 750 slot machines operate at the fair grounds year-round.

London's downtown mall, the Galleria, since 2000 has suffered after the collapse of Eaton's and the Hudson's Bay Company moving out of the mall. Currently the large spaces which were left empty by the departure of Eaton's and the Bay have been replaced by London's central library which now resides in that space. Other sections of the Galleria have also lost businesses and have been replaced by information centres for London's major post-secondary education schools, Fanshawe College and the University of Western Ontario. Some have accused London's extensive suburban malls and suburban expansion for causing business to be moving to the suburbs instead of remaining downtown.

For many years, London has been deemed a "test market" for Canada. International companies have used London to introduce their products and companies into Canada. They use London because it is considered an average Canadian city, in that respect similar to Winnipeg, Manitoba.[citation needed]

Demographics

According to the 2006 census, the city proper of London had a population of 352,395 people, 48.2% male and 51.8% female. Children under five accounted for approximately 5.2% of the resident population of London. [1] In mid-2001, 13.1% of the resident population in London were of retirement age (65 and over for males and females) compared with 13.2% in Canada, therefore, the average age is 36.9 years of age comparing to 37.6 years of age for all of Canada.

In the five years between 1996 and 2001, the population of metropolitan London grew by 3.8%, compared with an increase of 6.1% for Ontario province as a whole. Population density of metro London averaged 185.3 people per square kilometre, compared with an average of 12.6 for Ontario altogether.

The majority of Londoners profess a Christian faith, some 75.8% (Protestant 44%, Roman Catholic: 27.9%, other Christian, mostly Orthodox: 3.9%). Other religions include Islam: 2.7%, Buddhism: 0.6%, and Judaism: 0.4%. There are also centres for Theosophy and Eckankar devotees, as well as a centre for Unitarians. There is also an active Bahá'í community in London.

According to the 2006 census, the racial makeup of the city of London is as follows:

White: 87.2%, Latin American: 1.7%, Black: 1.4%, South Asian: 1.3%, mixed race: 1.3% Aboriginal: 1.3% [2]

Crime

Historically, crime in London has been low for a city of its size,[9] And the city recently experienced a 9% decrease in the overall crime rate. Like most cities of its size, a chapter of the Hells Angels have set here and the city formerly housed a chapter of the Outlaws Motorcycle Club. In 2005, however, London had a record 14 homicides, giving the city a per capita murder rate of 3.8 per 100,000, twice the 2004 national average and about a third higher than in Toronto, where much concern was voiced in 2005 over violent crimes.

Comparatively speaking, London manages its street crime well, though Marijuana can be easily found, though still illegal, as well as ecstasy. London has witnessed an increase in crack cocaine consumption and crystal meth use is also on the rise.[10] Pharmaceutical drugs, such as morphine, oxycodone and other opiates are increasing in use.[citation needed] London's illegal drug problems are of long standing; it was nicknamed "Speed City" in the 1970s[citation needed] due to widespread use of amphetamines.

Making headlines in the 1970s serial killer Russell Johnson operated in London, Ontario, and southwestern Ontario often scaling high-rise apartment buildings to reach his victims. He was captured and jailed in 1978.

Education

Elementary and Secondary

London elementary and secondary schools are under the control of four school boards: the Thames Valley District School Board, the London District Catholic School Board and the french first language school boards, le Conseil scolaire de district du Centre-Sud-Ouest and le Conseil scolaire de district des écoles catholiques du Sud-Ouest. See List of schools in London, Ontario.

Post-secondary

London is the home to two post-secondary institutions: the University of Western Ontario (UWO) and Fanshawe College, a community college.

UWO, founded in 1878, has 1,164 faculty members and almost 29,000 undergraduate and graduate students. It has consistently placed in the top three in the annual Maclean's magazine rankings of Canadian universities. The Richard Ivey School of Business, part of UWO, was formed in 1922 and has been ranked among the best business schools in the country; however, at present, the school is ranked fourth, behind Schulich, Queen’s, and Desautels.[11] UWO has three affiliated colleges: Brescia University College, founded in 1919, Canada's only university-level women's college; Huron University College, founded in 1863 (also the founding college of UWO) and King's University College, founded in 1954. These are liberal arts colleges with religious affiliations: Huron with the Anglican Church of Canada, King's and Brescia with the Roman Catholic Church.[12]

Fanshawe College has an enrolment of approximately 13,000 students, including 3,500 apprentices and more than 200 international students from over 80 countries, as well as almost 40,000 students in part-time continuing education courses. Fanshawe's Key Performance Indicators (KPI) have been over the provincial average for many years now, with increasing percentages year by year.[14]

The Ontario Institute of Audio Recording Technology (OIART) is also in London.

Sports

London is currently home to the London Knights of the Ontario Hockey League, who play at the John Labatt Centre, also known as the JLC. The JLC was the host arena of the 2005 Memorial Cup. The Knights were both 2004-2005 OHL and Memorial Cup Champions. They are by far the most popular sports team in the city. During the summer months, the London Majors of the Intercounty Baseball League play at historic Labatt Park. Other sports teams from London include:

- London Monarchs of the now defunct Canadian Baseball League played at Labatt Park.

- London Werewolves (1999-2002; moved to Canton, Ohio as the Coyotes) of the Frontier League, who played at Labatt Park and were league champions in 1999.

- London Tigers (1989-1993; moved to Trenton, New Jersey) of the AA Eastern League, who played at Labatt Park and were league champions in 1989-1990.

- London City of the Canadian Soccer League, the second tier of professional Canadian Association Football. The club were founded in 1973, and play their games at Cove Road Stadium.

- London Stallions in the Ontario Australian Football League

- London Silverbacks of the North American Football League

- London Beefeaters of the Ontario Football Conference

- The Forest City Thunderbirds of the Central Ontario Minor Football League

- London Aquatic Club

- London Silver Dolphins Swim Team

- London Falcons of the Ontario Varsity Football League

- London Gryphons women's soccer team

- Forest City Volleyball Club (youth volleyball club part of Ontario Volleyball Association run out of Fanshawe College)

- London Tecumsehs, 1877 pennant winners of the now defunct International Association

- London Nationals of the Western Ontario Hockey League

- London Lasers of the original Canadian Soccer League

- London St. George's Rugby Club; Senior and Junior Men's and Women's Rugby Teams

- London Rhythmic Gymnastics Club - home of Ontario and Eastern Canada champions Club's page

The University of Western Ontario teams play under the name Mustangs. The university's football team plays at TD Waterhouse Stadium. Western's Baseball Club (defending OUA champions) plays all their home games at Labatt Park.

Labatt Park, which opened in 1877, is the world's oldest operating baseball grounds still in its original location.

The Forest City Velodrome, located at the former London Ice House, is the only indoor cycling facility in Ontario and the third built in North America. It opened in 2005.

The World Lacrosse Championship was played in London from July 13 to July 22, 2006. Twenty-two teams from around the world competed, with Canada beating the U.S. in the final. The event also includes a "Festival of Lacrosse", with tournaments in at least six divisions, ranging from an under-19 division to an over-50 ("Centurion") division.

Media

*See related article: Media of London, Ontario London's main news channel is A-Channel. The main news paper is the London Free Press, and inside of it is the Londoner.

Arts and culture

London's diverse cultural offering boosts its tourism industry. The city is home to many festivals throughout the summer including the London International Children's Festival, the Home County Folk Festival, the Taste of London festival, London Ribfest which is the second largest rib festival in North America,[15] Pride London Festival one of the biggest Pride festivals in Ontario,[16] and Sunfest, a World music and culture festival — the second biggest in Canada after Caribana in Toronto.[17]

Musically, London is home to Orchestra London, the London Youth Symphony, the Amabile Choirs of London, Canada and also the Guy Lombardo Museum. There are several museums and theatrical facilities including Museum London, which is located at the Forks of the Thames. Museum London exhibits art by a wide variety of local, regional and national artists including Paul Peel and Greg Curnoe. London is also home to the Museum of Ontario Archaeology, owned by the University of Western Ontario (UWO), with a reconstructed Neutral Nation village, the McIntosh Gallery which is an art gallery on the UWO campus and The Grand Theatre which is a professional theatre with a secondary stage named the McManus Studio. Other places and events of artistic and cultural interest include:

- Wortley Village, an enticing blend of history, community, dining, shopping and nature in a few square kilometers a short walk southwest from downtown.

- Forest City Gallery, an artist-run centre, founded in 1973

- Fanshawe Pioneer Village, a reconstructed 19th century village

- Storybook Gardens, an amusement park/zoo for children

- London Regional Children’s Museum, a special place for children and their grown-ups to play and learn together.

- Home County Folk Festival, a Folk music festival

- London Fringe Festival

- London Balloon Festival, displays of hot air balloons

- Hawk Rocks the Park an annual Classic Rock music festival held in Harris Park by Radio Station The hawk.

- Western Fair, an annual agricultural fair and midway in September.

- Western Fair Raceway, a half-mile (802 m) harness racing track and simulcast centre; despite its name, it operates year-round. The grounds include a coin slot casino, a former IMAX theatre, and Sports and Agri-complex.

- John Labatt Centre, sports-entertainment complex

- London Rib-Fest, currently the second largest rib-fest in North America.

- Labatt Memorial Park, world's oldest, continuously used baseball grounds, since 1877

- TD Waterhouse Stadium, an all-purpose stadium at the University of Western Ontario

- Forest City Velodrome, an indoor bicycle track at the former London Ice House

- London Area Scouting - A youth organization with over thirty active groups.

- Spriet Children's Theatre, used primarily by The Original Kids theatrical company

- The Arts Project, an art gallery, workshop and theatre.

- The Royal Canadian Regiment Museum, Wolseley Barracks

- The Holy Spirit Marching Band, Portuguese Banda Filarmonica

- The Writers Resource Center is the home of the Canadian Poetry Association London Chapter.

- The London International Blues Festival

- The London Ontario Live Arts (LOLA) Festival

- Eldon House - The former residence of the prominent Harris Family and oldest surviving such building in London. The entire property was donated to the city of London in 1959, now heritage site.

Transportation

Road transportation

- London is present at the junction of Highway 401: the world's busiest highway, that connects the city to Toronto and Detroit, USA, and Highway 402 to Sarnia. Also, Highway 403, which diverges from the 401 at nearby Woodstock, Ontario, provides ready access to Brantford, Hamilton, the Golden Horseshoe area, and the Niagara Peninsula.

- Many smaller two-lane highways also pass through or near London including Kings Highways 2, 3, 4, 7 and 22. Many of these are "historical" names, however, as provincial downloading in the 1980s and 1990s put responsibility for most provincial highways onto municipal governments. Nevertheless, these roads continue to provide important access from London to nearby communities and locations in much of Western Ontario including Goderich, Port Stanley and Owen Sound.

- The Guy Lombardo Bridge section of Wonderland Road (between Springbank Drive and Riverside Drive) is London's busiest section of roadway, with more than 45,000 vehicles using the span on an average day.

Network problems

- Within London, as with many cities, traffic tends to congest in certain areas during rush hour. However, the lack of a municipal freeway (either through or around the city) as well as the presence of two significant railways (each with attendant switching yards and few over/under-passes) contributes heavily to this congestion. These conditions cause travel times to be highly variable with the time required to cross the city varying from 20 minutes to over an hour.

- London's public transit system is also lacking when compared to other Canadian cities similar to its size and area. The lack of bus routes and buses significantly hinders the public's ability to travel within the city if they do not possess their own vehicle or the finances to use a taxi. The London Transit Commission has been improving bus service over the years, but not enough to cope with the city's growing number of riders. Bus service is currently the only mode of public transit currently available to the public in London, unlike ground light rail or rapid transit networks used in other Canadian cities.

The "London Ring Road" controversy

London is currently one of the largest cities in North America not to have an urban freeway serving the metropolitan area. This is despite plans to construct such a road (around the city's periphery) which have existed for decades, but have recently been revived. Notable in the 1960s and early 1970s was an effort to route, through the north and east sections of the city or in the rural areas beyond, an expressway from Sarnia. The assorted route options (in-city that served users but disrupted neighbourhoods, or out-of-the-city that avoided neighbourhoods but did not serve city users) were fought over, but in the end, city council rejected the freeway, and instead accepted the now named Veterans Memorial Parkway to serve the east end.

Another freeway near the city's western edge is also under consideration, as future traffic volumes for the city may outpace capacity for the north/south western arteries, even with massive widening projects. Some Londoners have expressed concern that the absence of a local freeway may hinder London's economic and population growth, being far behind growth rates of other Canadian cities for some time. Many other Londoners have voiced concern that such a freeway would destroy environmentally sensitive areas and further contribute to London's already uncontrolled suburban sprawl.

Although there are many factors at play, proponents of the project attribute the lack of progress largely to litigation by environmental lobbies and local home-owners. Critics of the plan have voiced concern that the property-development companies that back the plan have little regard for the integrity and history of London's neighbourhoods. Nevertheless, the recent road capacity improvements to Veterans Memorial Parkway (formerly named Airport Road and Highway 100) in the industrialized east end does represent some small movement toward the pro-freeway agenda and may aid some traffic (largely coming off the 401) in reaching the east and north ends of the city. However, the Veterans Memorial Parkway has received criticism (like Airport Road in the past) for not being built as a proper highway and having intersections instead of interchanges.

Network Solutions

Since the 1970s, London has been more successful at urban road realignments that eliminated "jogs" in established traffic patterns over 19th-century street "mis-alignments": the Riverside Drive-Queens Avenue-Dundas Street linkup, the Springbank Drive-Horton Street linkup, the Bradley Avenue-Highbury interchange, the Wonderland Road bridge over the Thames River, and the Oxford Street West extension. Despite these improvements, some have claimed that London continues to have some of the worst roads in Ontario and that it has done little to improve its ranking.[18]

Rail

- London is on the Canadian National Railway main line between Toronto and Chicago (with a secondary main line to Windsor) and the Canadian Pacific Railway main line between Toronto and Detroit. VIA Rail operates regional passenger service through London station as part of the Quebec City-Windsor Corridor, with connections to the United States.

- Currently, London does not have any commuter rail stations set up along these lines. Because there is only one rail station in London's metropolitan area, local travel is not possible along these lines.

Bus

London is also an important destination for inter-city bus travellers. The Greyhound Canada express services to and from Toronto are heavily travelled, and connecting services radiate from London throughout southwestern Ontario and through to the American cities of Detroit, Michigan and Chicago, Illinois. The main bus company is London Transit.

Air

London International Airport (YXU) is served by airlines including Air Canada Jazz, WestJet and Northwest Airlink, and provides direct flights to popular national and international destinations. Many flights to nearby major airports Toronto and Detroit are flown daily, as well as a daily non-stops to Ottawa, Montreal, Winnipeg and Calgary.

Other

Like most cities of its size or larger, London has several taxi and for-hire limousine services and the London Transit Commission has 38 bus routes throughout the city. London is believed to be the only jurisdiction in North America where executive-class, sedan limousines can accept street-flags and wait for walk-on customers outside bars and restaurants,[citation needed] a popular by-product of the city's controversial and on-going taxi wars. Recently, London has constructed cycleways along some of its major arteries in order to encourage a reduction in automobile use.

Future Transportation Plans

The city of London is considering BRT (bus rapid transit), GLR (ground light rail), and/or HOV (high-occupancy vehicle) lanes to help it achieve its long-term transportation plan. Additional cycleways are planned for integration in road-widening projects, where there is need and sufficient space along routes. An expressway/freeway network is possible along the eastern and western ends of the city, from Highway 401 (and Highway 402 for the western route) past Oxford Street, potentially with another highway, joining the two in the city's north end. A parclo interchange between Highway 401 and Wonderland Road is also planned for completion by 2009, to move traffic more efficiently through the city's southwest end. Also in the works is revival of service on the London and Port Stanley Railway.

Miscellaneous

- Contrary to popular belief, London did not take on the name "Forest City" due to the number of trees in the city. In its early days, London was an isolated destination and one would have to walk through a forest to get there. So it can be said that London was a "city within a forest" and as such earned the nickname "The Forest City." In modern times, however, Londoners have become protective of the trees in the city, protesting "unnecessary" removal of trees. The City Council and tourist industry have created projects to replant trees throughout the city. [citation needed]

- In the past few years the "Forest City" has experienced an increase in the population of the Ash Borer beetle. This has caused some damage to local trees including the loss of some well established trees. Residents are mailed a notice yearly from Natural Resources of Canada advising them not to remove wood (including, but not limited to, broken tree limbs, bark, twigs and chips) from their properties unless through the curbside pick up program.

- Asteroid (12310) Londontario is named for the city.

- The tallest building in London is the One London Place, which currently stands as the tallest office tower in Ontario, outside of Toronto.

- The CFPL Television Tower, a 314 metre tall guyed TV tower, is the tallest structure in the city.

- In the acclaimed comic strip, For Better or For Worse, Michael Patterson studies at the University of Western Ontario in this city. Lynn Johnston selected London because it was a major university city that was a believable distance from Michael's parents (who live in a Toronto area suburb) to allow for occasional visits, but not for continual interaction. Furthermore, Johnston chose the city as a practical joke in anticipation that ignorant readers would confuse it with the British city and complain that she was being pretentious at having her character study in the United Kingdom until they were embarrassed when told of the Canadian city. Although Johnston had Michael initially study at an unnamed college, when she had him move study at the University, the actual school reacted with delight such as an official welcome from the administration for Mr. Patterson. In addition, when Michael is depicted graduating, Johnston clearly depicts the school's Alumni Hall for the occasion.

- In 1968, while performing In London, Johnny Cash proposed on stage to June Carter Cash[19].

Sister Cities

London currently has one Sister city:

Notable Londoners

A-B

- Philip Aziz, painter, sculptor, designer, heritage preservationist

- Karen Dianne Baldwin, 1982 Miss Universe

- Frederick Banting, co-discoverer of insulin, practiced in London and has both a museum dedicated to him and a high school named after him

- Joan Barfoot, Canadian author (fiction)

- Sir Adam Beck, who was instrumental in setting up the early grid to deliver hydro-electric publicly owned power from Niagara Falls to the rest of Ontario; former mayor of London

- Bobnoxious, rock band known for their singles "Won't Go Quietly" and "Big Cannons"

- Bill Brady, broadcast journalist and media executive, Member of the Order of Canada, former national director of The Canadian Heart & Stroke Foundation.

- Richard Maurice Bucke, 19th century pioneer in the modern treatment of the mentally ill

- Basia Bulat, singer, songwriter

- Tom R. Burgess, MLB pro baseball player (1954-1962) and MLB coach/ instructor until 1995

C-D

- Thomas Carling, founder of the Carling Brewing Company

- Sir John Carling, Thomas' son, provincial and federal politician

- Jeff Carter, Forward for the Philadelphia Flyers

- Jack Chambers, painter, filmmaker

- John H. Chapman, physicist

- Al Christie and his brother Charles Christie were Canadian pioneers in early Hollywood who built their own film studio

- Frank Colman, pro baseball player in 1940s with Pittsburgh Pirates and New York Yankees; also co-founded Eager Beaver Baseball Association in 1955

- Ward Cornell, radio drama and sports, television sports, host of Hockey Night in Canada, teacher (Pickering College)

- Logan Couture, OHL Player for the Ottawa 67's drafted by San Jose Sharks in

- Hume Cronyn, actor

- Greg Curnoe, painter, musician, member of the Nihilist Spasm Band, and author

- Peter Desbarats, former Global-TV anchor, author, former dean of journalism, University of Western Ontario

- Lolita Davidovich, actress

- Chris Daw, gold medalist in Turin 2006 Paralympics; wheelchair curling (skip)

- Alexander Dewdney, mathematician

- Christopher Dewdney, poet

- Chris Doty (1966-2006), award-winning documentary filmmaker, author and playwright

- Paul Duerden, youngest person to join the Canadian National Volleyball Team, currently a professional volleyball player

- Charley Fox, credited with strafing German Field Marshall Erwin Rommel's car and seriously injuring him in the process.

E-J

- Marc Emery, marijuana activist and libertarian

- The Essentials, a cappella group

- Murray Favro, Canadian artist and musician in the Nihilist Spasm Band

- Max Ferguson, CBC radio and TV personality, 1950s and 1960s

- Sam Gagner, NHL player for the Edmonton Oilers

- Victor Garber, actor

- George Gibson (Mooney), 1880-1967, catcher, Pittsburgh Pirates, won World Series in 1909; manager in MLB

- Ted Giannoulas, the Famous Chicken / San Diego Chicken mascot

- Ryan Gosling, actor

- Jeff Hackett, former NHL hockey goalie (ret. 2004)

- Paul Haggis, Academy Award-winning Hollywood screenwriter, director

- Richard B. Harrison (1864-1935), groundbreaking Black actor

- Frank Hawley (b. 1954), two-time World champion drag racing driver

- Garth Hudson, keyboard player in The Band

- Tommy Hunter, country singer

- Edwin Jarmain, Cable Television pioneer

- Jenny Jones, TV-talk show host

K-M

- Ingrid Kavelaars, actress

- Kittie, all female heavy metal band

- John Labatt, pioneer brewer

- Brett Lindros, former NHL hockey player, brother of Eric

- Eric Lindros, former NHL Player (ret. 2007), Drafted 1st overall in the 1991 Entry Draft by Quebec, brother of Brett

- John William Little, businessman and former mayor of London

- Paul Lewis (London, Ontario), a much-celebrated African American, born in 1889 and who died in 1974

- Gene Lockhart, actor who appeared in first Blondie and Dagwood films

- Guy Lombardo and brothers, world-famous bandleader and hydroplane racer

- Leo Loucks, Canadian World Champion Kickboxer 1986-87

- Donald Luce, former NHL centre for the New York Rangers, Detroit Red Wings, Buffalo Sabres and Toronto Maple Leafs

- Brad Marsh, hockey player for the Atlanta Flames and then the Calgary Flames

- Rachel McAdams, actress

- Cody McCormick, Colorado Avalanche NHL player.

- Roy McDonald, poet, diarist, local street-person/ personality

- Luke Macfarlane, actor

- David McLellan, Olympic freestyle swimmer

- Craig MacTavish, former NHL hockey player, current Edmonton Oilers head coach

- Rob McConnell, Canadian Music Hall-of-Fame jazz musician of Boss Brass fame

N-P

- Kate Nelligan, actress

- Christine Nesbitt, silver-medal winning Olympic speed-skater (women's team pursuit)

- Nihilist Spasm Band, pioneering noise music band

- Bert and Joe Niosi (brothers), band members of radio's Happy Gang.

- Ocean, Christian folk rock band

- Casey Patton, Canadian Boxer

- Paul Peel, painter

- David Peterson, premier of Ontario, 1985–1990

- Chris Potter, actor

- Skip Prokop, rock drummer/ songwriter, founder of the band, Lighthouse

- Brandon Prust, is a professional ice hockey forward currently playing for the Quad City Flames of the American Hockey League and the Calgary Flames of the National Hockey League.

R-S

- Wayne Ray, poet, author, founder of the Canadian Poetry Association and member of the founding Board for the London Arts Council

- Jack Richardson, C.M., award-winning record producer, Lifetime Achievement Juno Award recipient, Order of Canada recipient, and educator at Fanshawe College

- Michael Riley, television actor

- John P. Robarts, premier of Ontario, 1961-1971

- Jamie Romak, Professional Baseball Player, Drafted by the Atlanta Braves, currently a member of the Pittsburgh Pirates Organization

- Vic Roschkov Sr., newspaper editorial cartoonist/illustrator

- J. Philippe Rushton, researcher and academician at University of Western Ontario

- Craig Simpson, former NHL hockey player and coach

- Dave Simpson, former player with London Knights and current professor at the Richard Ivey School of Business

- David Shore, writer or producer for the television program House

- David Ellis Smith, co-founder of EllisDon construction (builders of the Rogers Centre), and brother of Don Smith

- Don Smith, co-founder of EllisDon construction (builders of the Rogers Centre), and brother of David Ellis Smith

- Timothy Snelgrove, founder of Timothy's World Coffee

- Ross Somerville, six-time Canadian Amateur Championship winner in golf, first Canadian to win U.S. Amateur in 1932

- Jude St. John, veteran, all-star player with Toronto Argonauts

- Lara St. John, violinist, sister of Scott St. John

- Scott St. John, violinist/violist, brother of Lara St. John

- Staylefish, Ska and Raggae Band

- Janaya Stephens, actress, star of the Left Behind movie series

- Adam Stern, Major League Baseball player with the Baltimore Orioles

- Sam Stout, Ultimate Fighting Championship competitor

- David Suzuki, geneticist, environmentalist, writer and broadcaster

T-Z

- Salli Terri, mezzo soprano

- Thine Eyes Bleed, metal band featuring Johnny Araya, brother of Slayer bassist and vocalist Tom Araya

- Tim Tindale, former American Football player with Buffalo Bills and Chicago Bears

- Five of the six Tolpuddle Martyrs, convicted in England for forming the first trade union there, settled in London

- Joe Thornton, 2006 NHL Art Ross and Hart Trophy winner and current NHL player

- Scott Thornton, current NHL player

- Tessa Virtue, ice dancer

- Jack Warner, co-founder of Warner Brothers Studios

- Jeff Willmore, visual and performance artist

- Tomasz Winnicki, white supremacist, anti-Semite and subject of complaints before the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal

- Marion Woodman, Jungian and feminist writer

Notable structures gallery

-

TD-Canada Trust bank building (Art Deco style)

-

View downstream along promenade of newly reconstructed West Dyke, Spring 2008

-

World's oldest ballpark, showing new downtown construction across river, Spring 2008

-

Castle-like entryway to Storybook Gardens

Further reading

- Frederick H. Armstrong and John H. Lutman, The Forest City: An Illustrated History of London, Canada. Burlington, Ontario: Windsor Publications; 1986.

- Orlo Miller, London 200: An Illustrated History. London: London Chamber of Commerce; 1993.

- L. D. DiStefano and N. Z. Tausky, Victorian Architecture in London and Southwestern Ontario, Symbols of Aspiration. University of Toronto Press; 1986

- Greg Stott, “Safeguarding ‘The Frog Pond’: London West and the Resistance to Municipal Amalgamation, 1883-1897.” Urban History Review 2000 29(1): 53-63.

References

- ^ According to the Canada 2006 Census.

- ^ Guy St-Denis, Byron:Pioneer Days in Westminster Township (Crinklaw Press, Lambeth Ontario,1985, ISBN 0-919939-10-4), pgs. 21-22.

- ^ Civilization.ca

- ^ "Ontario White Sulphur Springs". The London and Middlesex Historical Society. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ John H. Lutman, The Historic Heart of London (Corporation of the City of London, 1977), p. 6.

- ^ The Blackfriars Street Bridge was produced by the Wrought Iron Bridge Company of Canton, Ohio. However, a local, Isaac Crouse (1825–1915), was its contractor. Crouse was also responsible for portions of the construction of a number of other bridges in the City. Although many repairs and modifications have been made to the bridge, it remains a historic relic designated under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act, continuously serving its original purpose.

- ^ Gregory K. R. Stott, The Maintenance of Suburban Autonomy: The Story of the Village of Petersville-London West, Ontario, 1874-1897, MA thesis, Department of History, University of Western Ontario, 1999, Ch. Four.

- ^ "City of London: Heritage Building Registration".

- ^ City of London Crime Statistics

- ^ 100% Purity Crystal Meth taken off streets (retrieved on 2006-07-26)

- ^ MBA Guide to the best in graduate business school programs

- ^ Western Facts

- ^ FT.com / Business Education / Global MBA rankings

- ^ Fanshawe College Website

- ^ Ribfest at bgclondon.ca

- ^ Pride London Festival Website

- ^ Sunfest Website

- ^ Worst Roads in Canada

- ^ Johnny Cash and June Carter Cash Marriage Profile

See also

External links

- Everything London

- London Ontario Community Information

- London Indymedia

- Official City of London Website

- Museum of Ontario Archeology

- Local Weather

- Housing Access Centre (HAC)

- London Ontario Non-Profit Housing