Kepler's laws of planetary motion

Johannes Kepler's primary contributions to astronomy/astrophysics were his three laws of planetary motion. Kepler, a nearly blind though brilliant German mathematician, derived these laws, in part, by studying the observations of the keen-sighted Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. The article on Johannes Kepler gives a less mathematical description of the laws, as well as a treatment of their historical and intellectual context.

Sir Isaac Newton's later discovery of the laws of motion and universal gravitation depended strongly on Kepler's work. Although from the modern point of view, Kepler's laws can be seen as a consequence of Newton's laws, historically, it was the other way around: Kepler provided a mathematically distilled description of the empirical observations, which Newton then interpreted.

Kepler's laws of planetary motion

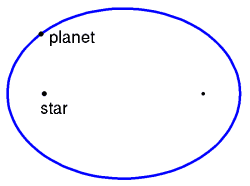

- Kepler's first law (1609): The orbit of a planet about a star is an ellipse with the star at one focus.

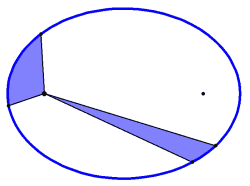

- Kepler's second law (1609): A line joining a planet and its star sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time.

- Kepler's third law (1618): The square of the sidereal period of an orbiting planet is directly proportional to the cube of the orbit's semimajor axis.

Kepler's first law

The orbit of a planet about a star is an ellipse with the star at one focus.

There is no object at the other focus of a planet's orbit. The semimajor axis, a, is half the major axis of the ellipse. In some sense it can be regarded as the average distance between the planet and its star, but it is not the time average in a strict sense, as more time is spent near apocentre than near pericentre.

Kepler's second law

A line joining a planet and its star sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time.

This is also known as the law of equal areas. Suppose a planet takes 1 day to travel from points A to B. During this time, an imaginary line, from the Sun to the planet, will sweep out a roughly triangular area. This same amount of area will be swept every day.

As a planet travels in its elliptical orbit, its distance from the Sun will vary. As an equal area is swept during any period of time and since the distance from a planet to its orbiting star varies, one can conclude that in order for the area being swept to remain constant, a planet must vary in velocity. The physical meaning of the law is that the planet moves faster when it is closer to the sun. This is because the sun's gravity accelerates the planet as it falls toward the sun, and decelerates it on the way back out.

Kepler's third law

The square of the sidereal period of an orbiting planet is directly proportional to the cube of the orbit's semimajor axis.

- P2 ~ a3

- P = object's sidereal period in years

- a = object's semimajor axis, in AU

Thus, not only does the length of the orbit increase with distance, also the orbital speed decreases, so that the increase of the sidereal period is more than proportional.

See the actual figures: attributes of major planets.

This law is also known as the harmonic law.

Accuracy and limitations

As discussed below, Kepler's third law needs to be modified when the orbiting body's mass is not negligible compared to the mass of the body being orbited. However, the correction in fairly small in the case of the planets orbiting the sun. A more serious limitation of Kepler's laws is that they assume a two-body system. This is a particularly bad approximation in the case of the earth-sun-moon system, and for calculations of the moon's orbit, Kepler's laws are far less accurate than the empirical method invented by Ptolemy hundreds of years before.

Because electrical forces also obey an inverse square law, Kepler's laws also apply to bodies interacting electrically. In the planetary model of the atom, the electrons were imagined to orbit the nucleus exactly like the planets orbiting the sun.

Kepler's laws do not include the emission of radiation. The emission of gravitational radiation is negligible in our solar system, but important in some stellar systems containing black holes or neutron stars. In the the planetary model of the atom, the emission of electromagnetic radiation should have led to the collapse of all atoms, and this was a hint that classical physics was in need of modification. Kepler's laws don't incorporate relativity, so, for example, they don't correctly predict the precession of Mercury's orbit.

Connection to Newton's laws and conservation laws

Kepler did not understand why his laws were correct; it was Isaac Newton who discovered the answer to this more than fifty years later. The second law can also be seen as a statement of conservation of angular momentum, which is a logical consequence of Newton's laws in the special case of a force that acts along the line connecting two objects.

Kepler's first law

Newton proposed that "every object in the universe attracts every other object along a line of the centers of the objects proportional to each objects mass, and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between the objects."

The following assumes that acceleration is of the form

- .

Recall that in polar coordinates:

In component form, we have:

Since and , the latter equation is equivalent to

- .

When integrated, this yields

- ,

- ,

for some constant , which can be shown to be the specific angular momentum. Now we substitute. Let:

The equation of motion in the direction becomes:

If , as Newton's law of gravitation claims, then:

where -k is our proportionality constant.

This differential equation has the general solution:

Replacing u with r and letting θ0=0:

- .

This is indeed the equation of a conic section with the origin at one focus. Thus, Newton's law of gravitation is a direct result of Kepler's first law.

Kepler's second law

Assuming Newton's laws of motion, we can show that Kepler's second law is consistent. By definition, the angular momentum of a point mass with mass and velocity is :

- .

where is the position vector of the particle.

Since , we have:

taking the time derivative of both sides:

since the cross product of parallel vectors is 0. We can now say that is constant.

The area swept out by the line joining the planet and the sun, is half the area of the parallelogram formed by and .

Since is constant, the area swept out by is also constant. Q.E.D.

Kepler's third law

Newton used the third law as one of the pieces of evidence used to build the conceptual and mathematical framework supporting his law of gravity. If we take Newton's laws of motion as given, and consider a hypothetical planet that happens to be in a perfectly circular orbit of radius r, then we have for the sun's force on the planet. The velocity is proportional to r/P, which by Kepler's third law varies as one over the square root of r. Substituting this into the equation for the force, we find that the gravitational force is proportional to one over r squared. (Newton's actual historical chain of reasoning is not known with certainty, because in his writing he tended to erase any traces of how he had reached his conclusions.) Reversing the direction of reasoning, we can consider this as a proof of Kepler's third law based on Newton's of gravity, and taking care of the proportionality factors that were neglected in the argument above, we have:

where:

- P = planet's sidereal period

- r = radius of the planet's circular orbit

- G = the gravitational constant

- M = mass of the sun

The same arguments can be applied to any object orbiting any other object. This discussion implicitly assumed that the planet orbits around the stationary sun, although in reality both the planet and the sun revolve around their common center of mass. Newton recognized this, and modified this third law, noting that the period is also affected by the orbiting body's mass. However typically the central body is so much more massive that the orbiting body's mass may be ignored. Newton also proved that in the case of an elliptical orbit, the semimajor axis could be substituted for the radius. The most general result is:

where:

- P = object's sidereal period

- a = object's semimajor axis

- G = 6.67 × 10−11 N · m2/kg2 = the gravitational constant

- M = mass of one object

- m = mass of the other object

For objects orbiting the sun, it can be convenient to use units of years, AU, and solar masses, so that G becomes 4π2, and with m<<M, and we have simply .

Solution for the motion as a function of time

Assume an orbit with semimajor axis a, semiminor axis b, and eccentricity ε. To convert the laws into predictions, Kepler began by adding the orbit's auxiliary circle (that with the major axis as a diameter) and defined these points:

- c center of auxiliary circle and ellipse

- s sun (at one focus of ellipse);

- p the planet

- z perihelion

- x is the projection of the planet to the auxiliary circle; then

- y is a point on the circle such that

and three angles measured from perihelion:

- true anomaly , the planet as seen from the sun

- eccentric anomaly , x as seen from the centre

- mean anomaly , y as seen from the centre

Then

giving Kepler's equation

- .

To connect E and T, assume then

- and

which is ambiguous but useable. A better form follows by some trickery with trigonometric identities:

(So far only laws of geometry have been used.)

Note that is the area swept since perihelion; by the second law, that is proportional to time since perihelion. But we defined and so M is also proportional to time since perihelion—this is why it was introduced.

We now have a connection between time and position in the orbit. The catch is that Kepler's equation cannot be rearranged to isolate E; going in the time-to-position direction requires an iteration (such as Newton's method) or an approximate expression, such as

via the Lagrange reversion theorem. For the small ε typical of the planets (except Pluto) such series are quite accurate with only a few terms; one could even develop a series computing T directly from M.[1]

External links

- Crowell, Benjamin, Conservation Laws, http://www.lightandmatter.com/area1book2.html, an online book that gives a proof of the first law without the use of calculus.