Korean language

error: ISO 639 code is required (help) The Korean language (한국어 / 조선어) is the most widely used language in Korea, and is the official language of both North and South Korea. The language is also spoken widely in neighbouring Yanbian, China. Worldwide, there are around 78 million Korean speakers, including large groups in the former Soviet Union, the United States, Canada, Brazil, Japan, and more recently the Philippines. The language is strongly associated with the Korean people.

The genealogical classification of Korean is debated. It is sometimes placed by linguists in the Altaic language family, though others considered it to be a language isolate. Korean is agglutinative in its morphology and SOV in its syntax.

The native Korean writing system, called hangul, is a phonemic alphabet. Sino-Korean characters, or hanja, are also used in writing. While the most commonly used words in the language are of native Korean origin, well over 50% of the vocabulary consists of words composed from hanja.

Names

"Korean" is not the name used by Korean speakers as the name of their language. The Korean names for the language are based on the names for Korea used in North and South Korea.

In North Korea, Korea is called Chosŏn (조선), and the language is most often called Chosŏnmal (조선말), or more formally, Chosŏnŏ (조선어).

In South Korea, Korea is called Hanguk (한국). There and outside of Korea, the language is most often called Hangungmal (한국말), or more formally, Hangugeo (한국어). The language is also sometimes referred to colloquially as Urimal (우리말) "our language". The standard language taught in schools is often referred to as Gugeo (국어) "national language".

All of Korea was also called Chosŏn, and so many important linguistic works written during that period also refer to the language by the names "Chosŏnŏ" or "Chosŏnmal."

Classification and related languages

Korean classification is often debated, but many Korean and Western linguists recognize Korean's kinship to the Altaic languages. Others consider it as being a separate language in a family of its own (a language isolate). On the other hand, many linguists believe that Japanese and Korean are related.

In Korea, the possibility of a Korean-Japanese linguistic relationship has not been fully studied; partly because the often strained relations between the two countries throughout history tend to make any discussion of a relationship between their languages a controversial one, and partly due to the difference in phonology. However, the Korean relationship with Altaic and proto-Altaic also have been much argued as of late. Korean is similar to Altaic languages in that they both have the absence of certain grammatical elements, including number, gender, articles, fusional morphology, voice, and relative pronouns (Kim Namkil). Korean especially bears some morphological resemblance to some languages of the Eastern Turkic group, namely Yakut.

However, in Korea and elsewhere, the possibility of a Baekje-Japanese linguistic relationship has been studied. Korean linguists point out that these languages are similar in phonology. For instance, it should be noted that both of these languages lack consonant-final sounds; however, are not totally void of them. Also, there are plenty of cognates between Baekje and Japanese. Exempli gratia, mir and mi mean "three" in Baekje and Japanese respectively. Furthermore, there are cultural links between Baekje and Japan: the people of Baekje used two Chinese characters for their surnames, like the people of Japan today. A Goguryeo-Japanese linguistic relationship has been suggested, but it has not been closely looked into by Korean linguists. Unlike the Baekje language, Goguryeo is rich with consonant-final words. (See Fuyu languages.)

In the late 19th century, Homer B. Hulbert, a British linguist, theorised that Korean is related to the Dravidian languages of India. His argument was based on Dravidian and Korean sharing syntatic similarities such as subject-object-verb word order, postpositions, absence of relative pronouns, modifiers preceding the head noun, and the copula and existential being two distinct parts of speech (Kim Namkil). Proponents of this theory point out that there are cognates between the Dravidian languages, particularly Tamil, and Korean. For example, the word nal means "day" and na means "I" or "me" in both Tamil and Korean. This theory is viewed by most linguists as only speculatory, since many verb-final languages share these syntactic traits.

Geographic distribution

Most of the speakers of the Korean language live in North and South Korea. However, there are some ethnic Koreans in China, Australia, the former Soviet Union, Japan, Brazil, and the United States.

Dialects

Korean has several dialects (called mal (literally speech), bang-eon, or saturi in Korean). The standard language (Pyojuneo or Pyojunmal) of South Korea is based on the dialect of the area around Seoul, and the standard for North Korea is based on the dialect spoken around P'yŏngyang. These dialects are similar, and in fact all dialects except that of Jeju Island are largely mutually intelligible. The dialect spoken there is classified as a different language by some Korean linguists. One of the most notable differences between dialects is the use of stress: speakers of Seoul Dialect use stress very little, and standard South Korean has a very flat intonation; on the other hand, speakers of Gyeongsang Dialect have a very pronounced intonation that makes their dialect sound more like a European language to western ears.

There is a very close connection between the dialects of Korean and the regions of Korea, since the boundaries of both are largely determined by mountains and seas. Here is a list of traditional dialect names and locations:

| Standard Dialect | Where Used |

| Seoul | Seoul, Incheon, Gyeonggi (South Korea); Kaesŏng (North Korea) |

| P'yŏngan | P'yŏngyang, P'yŏngan region, Chagang (North Korea) |

| Regional Dialect | Where Used |

| Chungcheong | Daejeon, Chungcheong region (South Korea) |

| Gangwon | Gangwon (South Korea)/Kangwŏn (North Korea) |

| Gyeongsang | Busan, Daegu, Ulsan, Gyeongsang region (South Korea) |

| Hamgyŏng | Rasŏn, Hamgyŏng region, Ryanggang (North Korea) |

| Hwanghae | Hwanghae region (North Korea) |

| Jeju | Jeju Island/Province (South Korea) |

| Jeolla | Gwangju, Jeolla region (South Korea) |

Sounds

Consonants

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Velar | Glottal | ||

| Plosives & affricates |

plain | ㅂ p | ㄷ t | ㅈ tʃ | ㄱ k | |

| tense | ㅃ b̬ | ㄸ d̬ | ㅉ d̬ʃ | ㄲ ɡ̬ | ||

| aspirate | ㅍ pʰ | ㅌ tʰ | ㅊ tʃʰ | ㅋ kʰ | ||

| Fricatives | plain | ㅅ s | ㅎ h | |||

| tense | ㅆ z̬ | |||||

| Nasal stops | ㅁ m | ㄴ n | ㅇ ŋ | |||

| Lateral approximant | ㄹ l | |||||

Example words for consonants:

| phoneme | IPA | Romanized | English |

| ㅂ p | [pal] | bal | 'foot' |

| ㅃ b̬ | [b̬al] | ppal | 'sucking' |

| ㅍ pʰ | [pʰal] | pal | 'arm' |

| ㅁ m | [mal] | mal | 'horse' |

| ㄷ t | [tal] | dal | 'moon' |

| ㄸ d̬ | [d̬al] | ttal | 'daughter' |

| ㅌ tʰ | [tʰal] | tal | 'riding' |

| ㄴ n | [nal] | nal | 'day' |

| ㅈ ts | [tʃal] | jal | 'well' |

| ㅉ d̬s | [d̬ʃal] | jjal | 'squeezing' |

| ㅊ tsʰ | [tʃʰal] | chal | 'kicking' |

| ㄱ k | [kal] | gal | 'going' |

| ㄲ ɡ̬ | [ɡ̬al] | kkal | 'spreading' |

| ㅋ kʰ | [kʰal] | kal | 'knife' |

| ㅇ ŋ | [paŋ] | bang | 'room' |

| ㅅ s | [sal] | sal | 'flesh' |

| ㅆ z̬ | [z̬al] | ssal | 'rice' |

| ㄹ l | [paɾam] | baram | 'wind' |

| ㅎ h | [hal] | hal | 'doing' |

The IPA symbol < ̬> (a subscript wedge) is used to denote the tensed consonants /b̬, d̬, ɡ̬, d̬s, z̬/. Its official IPA usage is for voiced consonants, which the tensed stops in Korean are not. The use of this diacritic along with the symbols for voiced consonants indicates that the glottal constriction is greater than that found in modal voicing. This is called stiff voice. The Korean tensed stops are produced with a partially constricted glottis and additional subglottal pressure, elements of stiff voice, which is how they are sometimes analysed.

Sometimes the tense consonants are indicated with the apostrophe-like symbol <ʼ>, but this is inappropriate, as IPA <ʼ> represents the ejective consonants, with their glottal movement and non-pulmonic air pressure, which the Korean tense consonants do not have.

There is ongoing debate as to whether the "tense" consonants are fortis or lenis, partially because those are poorly defined terms, and much of the academic literature is in a state of confusion.

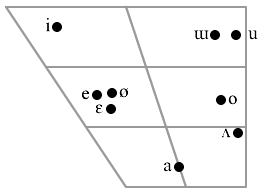

Vowels

|

|

Monophthongs

Korean has 8 different vowel qualities and a length distinction. Two more vowels, the close-mid front rounded vowel /ø/ and the close front rounded vowel /y/, can still be heard in the speech of some older speakers, but they have been largely replaced by the diphthongs [we] and [wi] respectively. In a 2003 survey of 350 speakers from Seoul, nearly 90% pronounced the vowel 'ㅟ' as [wi]. Length distinction is also decreasing; length distinction for all vowels can still be heard from older speakers, but many younger speakers do not always distinguish lengths consistently. The distinction between /e/ and /ɛ/ is another decreasing element in the speech of younger speakers, except when enunciated carefully. [e] seems to be the dominant form. Long /ʌː/ is actually [əː] for most speakers.

| i | [ɕiˈdʒaŋ] | sijang | 'hunger' | iː | [ˈɕiːdʒaŋ] | sijang | 'market' |

| e | [peˈɡɛ] | begae | 'pillow' | eː | [ˈpeːda] | beda | 'cut' |

| ɛ | [tʰɛˈjaŋ] | taeyang | 'sun' | ɛː | [ˈtʰɛːdo] | taedo | 'attitude' |

| a | [ˈmal] | mal | 'horse' | aː | [ˈmaːl] | mal | 'speech' |

| o | [poˈɾi] | bori | 'barley' | oː | [ˈpoːsu] | bosu | 'salary' |

| u | [kuˈɾi] | guri | 'copper' | uː | [ˈsuːbak] | subak | 'watermelon' |

| ʌ | [ˈpʌl] | beol | 'punishment' | əː | [ˈpəːl] | beol | 'bee' |

| ɯ | [ˈəːɾɯn] | eoreun | 'seniors' | ɯː | [ˈɯːmɕik] | eumsik | 'food' |

Diphthongs and glides

/j/ and /w/ are considered to be components of diphthongs rather than separate consonant phonemes.

| wi | dwi | dwi | 'back' | ɯi | ˈɯisa | uisa | 'doctor' | ||||

| je | ˈjeːsan | yesan | 'budget' | we | kwe | gwe | 'box' | ||||

| jɛ | ˈjɛːki | yaegi | 'story' | wɛ | wɛ | wae | 'why' | ||||

| ja | ˈjaːgu | yagu | 'baseball' | wa | kwaːˈil | kwa-il | 'fruits' | ||||

| jo | ˈkjoːs’a | gyosa | 'teacher' | ||||||||

| ju | juˈli | yuri | 'glass' | ||||||||

| jə | jəːgi | yeogi | 'here' | wʌ | Error: {{IPA}}: unrecognized language tag: mwʌ | 'what' |

Source: Handbook of the International Phonetic Association

Phonology

/s/ becomes an alveolo-palatal [ɕ] before [j] or [i]. This occurs with the tense fricative and all the affricates as well.

/h/ becomes a bilabial [ɸ] before [o] or [u], a palatal [ç] before [j] or [i], a velar [x] before [ɯ], a voiced [ɦ] between voiced sounds, and a [h] elsewhere.

/p, t, tʃ, k/ become voiced [b, d, dʒ, ɡ] between voiced sounds.

/l/ becomes alveolar flap [ɾ] between vowels, [l] or [ɭ] at the end of a syllable or next to another /l/, disappears at the beginning of a word before [j] in normal speech, and otherwise becomes [n] in normal speech.

All obstruents (plosives, affricates, fricatives) are unreleased [p̚, t̚, k̚] at the end of a word.

Plosive stops /p, t, k/ become nasal stops [m, n, ŋ] before nasal stops.

Some of these phonetic assimilation rules can be seen in the following:

- /tʃoŋlo/ is pronounced as [tʃoŋ.no]

- /hankukmal/ as [han.guŋ.mal]

Hangul spelling does not reflect these assimilatory pronunciation rules, but rather maintains the underlying morphology.

One difference between the pronunciation standards of North and South Korea is the treatment of initial [r], and initial [n] before [i] or [y]. For example,

- "labour" - north: rodong (로동), south: nodong (노동)

- "history" - north: ryŏksa (력사), south: yeoksa (역사)

- "lady" - north: nyŏja (녀자), south: yeoja (여자)

Vowel harmony

| Korean Vowel Harmony | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive/Yang Vowels | ㅏ (a) | ㅑ (ya) | ㅗ (o) | ㅛ (yo) | |||||||

| ㅐ (ae) | ㅘ (wa) | ㅚ (oe) | ㅙ (wae) | ||||||||

| Negative/Yin Vowels | ㅓ (eo) | ㅕ (yeo) | ㅜ (u) | ㅠ (yu) | |||||||

| ㅔ (e) | ㅝ (wo) | ㅟ (wi) | ㅞ (we) | ||||||||

| Neutral/Centre Vowels | ㅡ (eu) | ㅣ (i) | ㅢ (ui) | ||||||||

Traditionally, the Korean language has had strong vowel harmony; that is, in pre-modern Korean, as in most Altaic languages, not only did the inflectional and derivational affixes (such as postpositions) change in accordance to the main root vowel, but native words also adhered to vowel harmony. It is not as prevalent in modern usage, although it remains strong in onomatopoeia, adjectives and adverbs, interjections, and conjugation. There are also other traces of vowel harmony in Korean.

There are three classes of vowels in Korean: positive, negative, and neutral. The vowel ŭ is considered partially a neutral and negative vowel. The vowel classes loosely follow the mid (negative) and front (positive) vowels; they also follow orthography. Exchanging positive vowels with negative vowels usually creates different nuances of meaning, with positive vowels sounding diminuitive and negative vowels sounding crude.

Some examples:

- Onomatopoeia:

- 퐁당퐁당 (pongdangpongdang) and 풍덩풍덩 (pungdeongpungdeong), water splashing

- Adjectives/Adverbs:

- 모락모락 (morangmorak) and 무럭무럭 (mureongmureok) can both be translated as "rapidly" or "densely", but they are not interchangeable:

- 연기가 모락모락 난다. (yeongiga morangmorak nanda) Smoke rises up.

- 나무가 무럭무럭 자란다. (Namuga mureongmureok jaranda) The tree grows well.

- 모락모락 (morangmorak) and 무럭무럭 (mureongmureok) can both be translated as "rapidly" or "densely", but they are not interchangeable:

- Emphasised Adjectives:

- 노랗다 (norata) means plain yellow, while its negative, 누렇다 (nureota) means very yellow

- 파랗다 (parata) means plain blue, while its negative, 퍼렇다 (peoreota) means deep blue

- Particles at the end of verbs:

- 잡다 (Japda) (to catch) → 잡았다 (Jabatda) (caught)

- 접다 (Jeopda) (to fold) → 접었다 (Jeobeotda) (folded)

- Interjections:

- 아이고 (Aigo) and 어이구 (Eoigu) meaning "oh my!"

- 아하 (Aha) and 어허 (Eoheo) meaning "indeed" and "well" respectively

Grammar

Korean is an agglutinative language. The basic form of a Korean sentence is Subject-Object-Verb (SOV), and modifiers precede the modified word. As a side note, a sentence can break the SOV word order, however, it must end with the verb. In contrast to the Korean word order, in English, one would say, "I'm going to the store to buy some food," in Korean it would be: *"I food to-buy in-order-to store-to going-am."

In Korean (as in English), "unnecessary" words (see theme and rheme) can be left out of a sentence as long as the context makes the meaning clear. A typical exchange might translate word-for word to the following:

- H: "가게에 가세요?" (gage-e gaseyo?)

- G: "예." (ye.)

- H: *"store-to going?"

- G: "yes."

which in English would translate to:

- H: "Going to the store?"

- G: "Yes."

Unlike most European languages, Korean does not conjugate verbs using agreement with the subject, and nouns have no gender. Instead, verb conjugations depend upon the verb tense and on the relation between the people speaking. When talking to or about friends, you would use one conjugate ending, to your parents, another, and to nobility/honoured persons, another. This loosely echoes the T-V distinction of most Indo-European languages.

Speech levels and honorifics

The relationship between a speaker or writer and his or her subject and audience is paramount in Korean, and the grammar reflects this. The relationship between speaker/writer and subject is reflected in honorifics, while that between speaker/writer and audience is reflected in speech level.

Honorifics

When talking about someone superior in status, a speaker or writer has to use special nouns or verb endings to indicate the subject's superiority. Generally, someone is superior in status if he/she is an older relative, a stranger of roughly equal or greater age, or an employer, teacher, customer, or the like. Someone is equal or inferior in status if he/she is a younger stranger, student, employee or the like. On rare occasions (like when someone wants to pick a fight), a speaker might speak to a superior or stranger in a way normally only used for, say, animals, but no one would do this without seriously considering the consequences to their physical safety first!

One way of using honorifics is to use special nouns in place of regular nouns with "honorific" ones. A common example is using 진지 (jinji) instead of 밥 (bap) for "food". More often, special nouns are used when speaking about relatives. Thus, the speaker/writer may address his own grandmother as 할머니 (halmeoni) but refer to someone else's grandmother as 할머님 (halmeonim). The honorific suffix -님 (-nim) is affixed to many kinship terms to make them honorific; thus, 형님 (hyeongnim) is the formal term for an older sibling of the same sex (derived from 형 (hyeong,) the informal term for man's older brother; 언니 (eonni) is the informal term for a woman's older sister).

All verbs can be converted into an honorific form by adding the infix -시- (-si-, pronounced shi) after the stem and before the verb ending. Thus, 가다 (gada, "go") becomes 가시다 (gasida). A few verbs have special honorific equivalents. Therefore 계시다 (gyesida) is the honorific form of 있다 (itda, "exist"); 드시다 (deusida) and 잡수시다 (japsusida) is the honorific form of 먹다 (meokda, "eat"); and 주무시다 (jumusida) is the honorific form of 자다 (jada, "sleep").

A few verbs have special humble forms, used when the speaker is referring to him/herself in polite situations. These include 드리다 (deurida) and 올리다 (ollida) for 주다 (juda, "give"). Deurida is substituted for juda when the latter is used as an auxiliary verb, while ollida — which literally means "raise up" — is used for juda in the sense of "offer".

Pronouns in Korean have their own set of polite equivalents: thus, 저 (jeo) is the humble form of 나 (na, "I"); 저희 (jeoheui) is the humble form of 우리 (uri, "we"); and 당신 (dangsin, "friend," but only used as a form of address and more polite than "chingu", the usual word for "friend"; also, whereas uses of other humble forms are straightforward, "dangsin" must be used only in specific social contexts, such as between two married couple — "dangsin" can often be used in ironic sense when used between strangers) is the honorific form of 너 (neo, "you" (singular). Note: in general, Koreans avoid using second person singular pronoun, especially when using honorific forms, and either i) use the person's name, kinship term, or title in place of "you" in English, ii) use plural 여러분 yeoreobun where applicable, or iii) avoid using a pronoun, relying on context to supply meaning instead).

Speech levels

There are no fewer than 7 verb paradigms or speech levels in Korean, and each level has its own unique set of verb endings which are used to indicate the level of formality of a situation. Unlike "honorifics" — which are used to show respect towards a subject — speech levels are used to show respect towards a speaker's or writer's audience. The names of the 7 levels are derived from the non-honorific imperative form of the verb 하다 (hada, "do") in each level, plus the suffix 체 ('che'), which means "style."

The highest 5 levels use final verb endings, while the lowest 2 levels (해요체 haeyoche and 해체 haeche) use non-final endings and are called 반말 (banmal, "half-words") in Korean. (The haeyoche in turn is formed by simply adding the non-final ending -요 (-yo) to the haeche form of the verb.)

Taken together, honorifics and speech levels form a cartesian product of 14 basic verb stems. Here is a table giving the 7 levels, the present indicative form of the verb 하다 (hada, "do" in English) in each level in both its honorific and non-honorific forms, and the situations in which each level is used.

| Speech Level | Non-Honorific Present Indicative of "hada" | Honorific Present Indicative of "hada" | Level of Formality | When Used |

| Hasoseoche (하소서체) |

hanaida (하나이다) |

hashinaida (하시나이다) |

Extremely formal and polite | Traditionally used when addressing a king, queen, or high official; now used only in historical dramas and the Bible |

| Hapshoche (합쇼체) |

hamnida (합니다) |

hashimnida (하십니다) |

Formal and polite | Used commonly between strangers, among male co-workers, by TV announcers, and to customers |

| Haoche (하오체) |

hao (하오) |

hasho (하쇼), hashio (하시오) |

Formal, of neutral politeness | Spoken form only used nowadays among some older people. Young people sometimes use it as an Internet dialect. |

| Hageche (하게체) |

hane (하네) |

hashine (하시네) |

Formal, of neutral politeness | Generally only used by some older people when addressing younger people, friends, or relatives |

| Haerache (해라체) |

handa (한다) |

hashinda (하신다) |

Formal, of neutral politeness or impolite | Used to close friends, relatives of similar age, or younger people; also used almost universally in books, newspapers, and magazines; also used in reported speech ("She said that...") |

| Haeyoche (해요체) |

haeyo (해요) |

haseyo (하세요) (common), hasheoyo (하셔요) (rare) |

Informal and polite | Used mainly between strangers, especially those older or of equal age. Traditionally used more by women than men, though in Seoul many men prefer this form to the Hapshoche (see above). |

| Haeche (해체) |

hae (해) (in speech), hayeo (하여) (in writing) |

hasheo(하셔) |

Informal, of neutral politeness or impolite | Used most often between close friends and relatives, and when addressing younger people. It is never used between strangers unless the speaker wants to pick a fight. |

Vocabulary

The core of the Korean vocabulary is made up of native Korean words. More than 50% of the vocabulary, however, is made up of Sino-Korean words, which are words borrowed from Chinese. To a much lesser extent, words have also been borrowed from Mongolian, Sanskrit, and other languages. In modern times, many words have also been borrowed from Western languages such as German and, more recently, English.

The numbers are a good example of borrowing. Like Japanese, Korean has two number systems — one native and one borrowed from the Chinese — so Korean, Chinese, Japanese, and some other languages such as Thai all appear to have similar words for numbers.

Writing system

The Korean language was originally written using "Hanja", or Chinese characters; it is now mainly written in Hangul, the Korean alphabet, optionally mixing in Hanja to write Sino-Korean words. The government in South Korea still teaches 1800 Hanja characters to its children, while the Pyoengyang has abolished the use of Chinese characters decades ago. North Korean immigrants in South Korea have a hard time learning Chinese characters. Hangul consists of 24 letters — 14 consonants and 10 vowels that are written in syllabic blocks of 2 to 5 characters. Unlike the Chinese writing system (including Japanese Kanji), Hangul is not an ideographic system. The shapes of the individual Hangul letters were traditionally attributed to the physical morphology of the tongue, palate, and teeth.

Below is a chart of the Korean alphabet's symbols and their canonical IPA values:

| IPA | p | t | c | k | b̬ | d̬ | ɟ̬ | ɡ̬ | pʰ | tʰ | cʰ | kʰ | s | h | z̬ | m | n | ŋ | w | r | j |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hangul | ㅂ | ㄷ | ㅈ | ㄱ | ㅃ | ㄸ | ㅉ | ㄲ | ㅍ | ㅌ | ㅊ | ㅋ | ㅅ | ㅎ | ㅆ | ㅁ | ㄴ | ㅇ | ㄹ |

| IPA | i | e | ɛ | a | o | u | ʌ | ɯ | ɯi | je | jɛ | ja | jo | ju | jʌ | wi | we | wɛ | wa | wʌ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hangul | ㅣ | ㅔ | ㅐ | ㅏ | ㅗ | ㅜ | ㅓ | ㅡ | ㅢ | ㅖ | ㅒ | ㅑ | ㅛ | ㅠ | ㅕ | ㅟ | ㅞ | ㅙ | ㅘ | ㅝ |

See also: Hangul consonant and vowel tables

Modern Korean is written with spaces between words, a feature not found in the other CJK languages (Chinese and Japanese). Korean punctuation marks are almost identical to Western ones. Traditionally, Korean was written in columns from top to bottom, right to left, much the same as in other East Asian cultures. Korean is still sometimes written in columns (especially in poetry), but is now usually written in rows from left to right, top to bottom.

Differences in the language between North Korea and South Korea

The Korean language used in the North and the South exhibits differences in pronunciation, spelling, grammar and vocabulary.

Pronunciation

In North Korea, palatization of /si/ is optional, and /tʃ/ can be pronounced as [z] in between vowels.

Words that are written the same way may be pronounced differently, such as the examples below. The pronunciations below are given in Revised Romanization, McCune-Reischauer and Hangul, the last of which represents what the Hangul would be if one writes the word as pronounced.

| Word | Meaning | Pronunciation | |||

| North (RR/MR) | North (Hangul) | South (RR/MR) | South (Hangul) | ||

| 넓다 | wide | neoptta (nŏpta) | 넙따 | neoltta (nŏlta) | 널따 |

| 읽고 | to read (continuative form) |

ikko (ikko) | 익꼬 | ilkko (ilko) | 일꼬 |

| 압록강 | Amnok (Yalu) River | amrokgang (amrokkang) | 암록강 | amnokgang (amnokkang) | 암녹강 |

Spelling

Some words are spelt differently by the North and the South, but the pronunciations are the same.

| Word spelling | Meaning | Pronunciation (RR/MR) | Remarks | |

| North | South | |||

| 해빛 | 햇빛 | sunshine | haetbit (haetpit) | The "sai siot" (ㅅ) is not written out in the North. |

| 벗꽃 | 벚꽃 | cherry blossom | beotkkot (pŏtkkot) | |

| 못읽다 | 못 읽다 | cannot read | monnikda (monnikta) | Spacing. |

| 한나산 | 한라산 | Hallasan | hallasan (hallasan) | An uncommon occasion when nn is pronounced like ll in the North. |

Both pronunciation and spelling

Some words have different spellings and pronunciations in the North and the South, some of which were given in the "Phonology" section above:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

| North spelling | North pronun. | South spelling | South pronun. | ||

| 력량 | ryeongryang (ryŏngryang) | 역량 | yeongnyang (yŏngnyang) | strength | Korean words originally starting in r or n have their r or n dropped in the South Korean version if the sound following it is an i or y sound. |

| 로동 | rodong (rodong) | 노동 | nodong (nodong) | work | Korean words originally starting in r have their r changed to n in the South Korean version if the sound following it is a sound other than i or y. |

| 원쑤 | wonssu (wŏnssu) | 원수 | wonsu (wŏnsu) | enemy | |

| 라지오 | rajio (rajio) | 라디오 | radio (radio) | radio | |

Grammar

Some grammatical constructions are also different:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

| North spelling | North pronun. | South spelling | South pronun. | ||

| 되였다 | doeyeotda (toeyŏtta) | 되었다 | doeeotda (toeŏtta) | past tense of 되다 (doeda/toeda), "to become" | All similar grammar forms in the North use 여 instead of the South's 어. |

| 고마와요 | gomawayo (komawayo) | 고마워요 | gomawoyo (komawŏyo) | thanks | ㅂ-irregular verbs in the North use 와 (wa) for all those with a positive ending vowel; this only happens in the South if the verb stem has only one syllable. |

| 할가요 | halgayo (halkayo) | 할까요 | halkkayo (halkkayo) | Shall we do? | Although the hangul differ, the pronunciations are the same (i.e. with the tensed ㄲ sound). |

Vocabulary

Some vocabulary is different between the North and the South:

| Word | Meaning | Remarks | |||

| North spelling | North pronun. | South spelling | South pronun. | ||

| 문화주택 | munhwajutaek (munhwajut'aek) | 아파트 | apateu (ap'at'ŭ) | flat ("apartment") | 아빠트 (appateu/appat'ŭ) is also used in the North. |

| 조선말 | joseonmal (chosŏnmal) | 한국말 | han-gungmal (han'gungmal) | Korean language | |

Others

In the North, 《 and 》 are the symbols used for quotes; in the South, quotation marks equivalent to the English ones, “ and ”, are used.

See also

- Common phrases in Korean

- Korean romanization

- Korean count word

- Korean language and computers

- List of English words of Korean origin

- List of Korea-related topics

External links

- kangmi | extensive list of links for English-speaking students of Korean

- Learn Korean

- Korean lessons

- English-Korean Dictionary

- Korean - English Dictionary: from Webster's Rosetta Edition.

- Ethnologue report for Korean

- Korea Fan Translated Term Handbook

- Korean Language Institute at Yonsei University

- Korean Course at Sogang University

- http://www.ickl.or.kr/ International Circle of Korean Linguistics (ICKL)

- International Association for Korean Language Education (IAKLE)

- KOREAN through ENGLISH at Ministry of Culture and Tourism

- Dongari Korean-English Conversation Exchange Group, San Francisco, CA, USA

- Learn and listen to useful expressions in Korean

- Naver dictionary site: Korean <=> Korean / English / Chinese / Japanese, English <=> English and Thesaurus (Collins), a Hanja dictionary, a terminology dictionary and a Korean encyclopaedia