Guqin

The guqin 古琴 also traditionally referred to simply as qin 琴 ("qin" is a generic term for stringed instruments, but by the 20th century, with many instruments using the word qin in their names, "gu" 古 meaning ancient, was added to distinguish it from others), is a traditional Chinese musical instrument. It belongs to the zither family of instruments, although it is sometimes inaccurately called a lute. The qin is not to be confused with the guzheng 古箏, another Chinese zither with 16-26 strings supported by bridges.

Unlike the guzheng, the qin is a fretless instrument with a range of about four octaves, depending on the techniques employed. It nearly always has seven strings, although some ancient guqins had five, or even ten strings. A plucked instrument, the qin is played with numerous playing techniques, of which the use of harmonics is one of the most important; it is capable of playing around 119 harmonics.

History 歷史

The most revered of all Chinese musical instruments, the qin has been in existence for some 3000 years. There are numerous references to the qin in the old Chinese classics that pre-date Confucius, but it is clear that these refer to the instrument in a prototypical or earlier form, certainly not the instrument that is recognised as a qin in contemporary times. The form of the qin that is recognizable today appears to have been set around the late Han dynasty, where a contemporaneous document "Qinfu" (a poetical essay in praise of the qin) by Ji Kang (one of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove) describes the instrument in a recognizable form. There are no specimens surviving from that era that have been verified. The earliest surviving qin have been reliably dated to the middle and late Tang periods, the most famous being the instrument named "Jiuxiao Huanpei" 九霄環佩 made by Lei Wei 雷威, which was recently sold in an auction. Played by Li Xiangting, he said that it was the best playable antique qin in existence.

Mentions in Chinese literature 文體記在

When consulting ancient Chinese texts, one will come across frequent references to the qin. Such references are particularly frequent in poetry of the Tang period. In the Shijing 詩經 (Book of Songs), several poems mention the qin:

- 我有嘉賓 鼓瑟鼓琴 "I have fine guests; so I strum the se, strum the qin..."

- 夫妻好合 如鼓琴瑟 "Husband and wife in love with each other; like the strumming of qin and se..."

- 窈窕淑女 琴瑟友之 "Fair and gentle is the maiden; qin and se are friends to her..."

- 琴瑟在御 莫不靜好 "Qin and se are in my carriage; there is none who likes silence..."

Ancient sources 古籍

- Qin Cao 琴操 by Cai Yong 蔡邕 (Han, a list of qin pieces played at the time with their descriptions)

- Qin Shuo 琴說 by Liu Xiang 劉向 (Han)

- Qin Fu 琴賦 by Ji Kang 嵇康 (Wei Jin, poetical essay in praise of the qin)

- Qin Lun 琴論 by Xie Zhuang 謝莊 (Wei Jin)

- Qinsheng Lutu 琴聲律圖 by Qu Zhan 麴瞻 (Wei Jin)

- Qinyong Zhifa 琴用指法 by Chen Zhongru 陳仲儒 (Wei Jin, explanation of finger techniques used at the time)

- Qin Jue 琴訣 by Bi Yijian 薛易簡 (Sui Tang)

- Qinshu Zhengsheng 琴書正聲 by Chen Kangshi 陳康士 (Sui Tang)

- Qin Shi 琴史 by Zhu Changwen 朱長文 (Song Yuan, a historical account of the qin)

- Qin Shu 琴述 by Yuan Jue 袁桷 (Song Yuan)

- Qin Jian 琴箋 by Cui Zhuandu 崔尊度 (Song Yuan)

- Qin Yi 琴議 by Liu Jie 劉藉 (Song Yuan)

- Qinlu Fawei 琴律發微 by Chen Minzi 陳敏子 (Song Yuan)

- Lun Qin 論琴 by Cheng Yujian 成玉(石+間) (Song Yuan)

- Qinsheng Shilufa 琴聲十六法 by Liang Qian 冷謙 (Ming, an explanation of different styles of qin music)

- Xishan Qinkuang 谿山琴況 by Xu Qingshan 徐青山 (Ming, an explanation of different styles of qin music)

- Gu Qin Baze 鼓琴八則 by Dai Yuan 戴源 (Qing)

- Qinxue Congshu 琴學叢書 (Late Qing, qinpu but contains many volumes on qin lore and discussion of qin)

- Yugu Zhai Qinpu 與古齋琴譜 by Zhu Tongjun 祝桐君 (Late Qing, manual for constructing qins, etc)

Schools and players 琴派琴家

Because of the difference in geography in China, many qin schools or 'qin pai' 琴派 developed over the centuries. Such schools generally formed around areas where qin activity was greatest. Some famous schools include Guangling 廣陵, Yushan 虞山 (Shanghai 上海), Shu 蜀 (Sichuan 四川), Zhucheng 諸城, Mei'an 梅庵, Min 閩 (Fujian 福建), Pucheng 浦城, Jiuyi 九嶷, Zhe 浙 and Shan'nan 山南.

There have been many notable players through the ages 古代琴家:

- Confucius 孔子 (philosopher)

- Bo Ya 伯牙 (Qin player of the Spring and Autumn Period)

- Cai Yong 蔡邕 (Han musician, author of Qin Cao)

- Sima Xiangru 司馬相如 (Han poet)

- Ji Kang 嵇康 (Sage of the Bamboo Grove, musician and poet)

- Li Bai 李白 (Tang poet)

- Bai Juyi 白居易 (Tang poet)

Contemporary players 現代琴家:

- Guan Pinghu 管平湖 (dec.): Possibly the greatest qin player of the 20th century. Dapued many qin scores such as Liu Shui and Guangling San. In 1977, his recording of "Liu Shui" (Flowing Water) was chosen to be included in the Voyager Golden Record, a collection of world music sent into space on the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecrafts

- Zha Fuxi 查阜西 (dec.): Great researcher of qin music, specialising in qin songs

- Wu Jinglue 吳景略 (dec.): Master of the Yushan School

- Pu Xuezhai 薄雪齋 (dec.): The brother of the last emperor, Puyi

- Zhang Ziqian 張子謙 (dec.): Master of the Guangling School

- Yao Bingyan 姚丙炎 (dec.): Dapued the classic version of Jiu Kuang in triple-time rhytmn

- Wei Zhongyue 衛仲樂 (dec.): An orphan, but a master of many Chinese instruments, including pipa and dizi

- Li Xiangting 李祥霆: Current president of the Bejing Guqin Society and master guqin player

- Gong Yi 龔一: Master from the Shanghai Conservatory

- Wu Wenguang 吳文光: Son of Wu Jinglue

- Wu Zhao 吳釗: Former president of the Beijing Guqin Society

- Yu Shaoze 喻紹澤 (dec.): Transmitter of the Shu School

- Cai Deyun 蔡德允: Head of the Yinyin Shi Qinshe of Hong Kong, oldest qin player alive today (100 years old in 2004)

- Wu Zhaoji 吳兆基: Transmitter of the Wu style

- Zeng Chengwei 曾成偉: Master guqin maker as well as transmitter of the Shu School

- Chen Changlin 陳長林: Transmitter of the Min School

- Lin Youren 林友人: A player of the Guangling school

- Tong Kin-woon 唐健垣: Hong Kong guqin player and teacher, chief editor of Qinfu 琴府, a composite volume of ancient scores (not to be confused with the Qin Fu of Ji Kang). As well, a master of the guzheng and nanyin.

Playing technique 指法

The qin is said to be capable of creating three distinctively different "sounds." The first is san yin 散音, which means "scattered sounds." This meant simply pluck the required string to sound an open note. The second is fan yin 泛音, or "floating sounds." These are harmonics, and the player simply lightly touches the string with one or more fingers of the left hand at a position indicated by the hui dots, pluck and lift, creating a crisp and clear sound. The third is an yin 按音 / 案音 / 實音 / 走音, or "stopped sounds." This forms the bulk of all qin pieces and requires the player to press on a string with a finger or thumb of the left hand until it connects with the surface board, then pluck. Afterwards, the hand can slide up and down, thereby modifying the pitch.

There are eight basic right hand finger techniques: pi 劈 (thumb pluck outwards), tou 托 (thumb pluck inwards), mo 抹 (index in), tiao 挑 (index out), gou 勾 (middle in), ti 剔 (middle out), da 打 (ring in), and zhai 摘 (ring out); the little finger is not used. Out of these basic eight, their combinations create many. Cuo 撮 is to pluck two strings at the same time, lun 輪 is to pluck a string with the ring, middle and index finger out in quick succession, the suo 鎖 technique involves plucking a string several times in a fixed rhythm, bo 撥 cups the fingers and attacks two strings at the same time, and gun fo 溒拂 is to create glissandi by runnning up and down the strings continuously with the index and middle fingers. These are just a few.

Left hand techniques start from the simple pressing down on the string (mostly with the thumb between the flesh and nail, and the ring finger), sliding up or down to the next note (shang 上 and xia 下), to vibrati by swaying the hand (yin 吟 and rou 揉) there are as many as 15 plus different forms of vibrato), plucking the string with the thumb whilst the ring finger stops the string at the lower position (qiaqi 掐起 / 搯起), to more difficult techniques such as pressing on several strings at the same time.

Techniques executed by both hands in tandem are more difficult to achieve, like qia cuo san sheng 掐撮三聲 (a combination of hammering on and off then plucking two strings, then repeating), to more stylised forms, like pressing of all seven strings with the left, then strumming all the strings with the right, then the left hand quickly moves up the qin, creating a 'bloommmmmmmmmmmmmmm' sound like a bucket of water being thrown in a deep pool of water (this technique is used in the Shu style of Liu Shui to create the sound of water).

In order to master the qin, there are in excess of 50 different techniques that must be mastered. Even the most commonly used (such as tiao) are difficult to get right without proper instruction from a teacher. Also, certain techniques vary from teacher to teacher and school to school.

Tablature and notation 琴譜

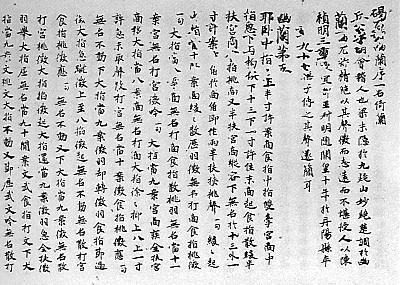

Traditional qin music was written in various forms of tablature, with the most recent classical form being settled around the 12th century CE. An earlier form of music notation from the Tang era survives in just one manuscript, dated to the 10th century CE, called Jieshi diao: You Lan 碣石調幽蘭 (The Solitary Orchid). It is written in a notation called "wenzi pu" 文字譜 (literally "written notation"), which is basically written out using ordinary written characters of the language of the period, comprising a step by step method and description of how to play the piece. Later in the Tang Dynasty, a qin player named Cao Rou 曹柔 simplified the notation, using only the important elements of the characters (like string number, plucking technique, hui number and which finger to stop the string) and combined them into one character notation. This meant that instead of having two lines of written text to describe a few notes, a single character could represent one note, or sometimes as many as nine. This notation form was called "jianzi pu" 減字譜 and it was a great leap forward for recording qin pieces. It was so successful that from the Ming dynasty onwards, a great many "qinpu" 琴譜 (qin tablature collections) appeared, the most famous and useful being "Shenqi Mipu" (The Mysterious and Marvellous Tablature) compiled by Zhu Quan 朱勸, the 17th son of the founder of the Ming dynasty. In the 1960s, Zha Fuxi discovered more than 100 qinpu that contain well over 3000 pieces of written music. Sadly, many qinpu compiled before the Ming dynasty are now lost, and many pieces have remained unplayed for hundreds of years.

First section of Youlan, showing the name of the piece: 碣石調幽蘭第五 "Jieshi Diao Youlan No.5", the preface describing the piece's origins, and the tablature in longhand form.

Another major change in the tablature happened during the Qing period. Before, the recording of the note positions between hui were only approximations. For example, to play sol on the seventh string, the position the player must stop is between the 7th and 8th hui. The tablature of Ming times would only say "between 7 and 8" 七八日(間) or for other positions "below 6" 六下 or even say "11" 十一 (when the correct position is slightly higher). During the Qing, this was replaced by the decimal system. The space between two hui were split into 10 'fen' 分, so the tablature can indicate the correct position of notes more accurately, so for the examples above, the correct positions are 7.6, 6.2 and 10.8 respectively. Some even went further to split one fen into a further 10 'li'厘, but since the distance is too minute to affect the pitch to a large degree, it was considered impractical to use.

First leaf of the third volume of Shenqi Mipu

First page / leaf of volume 3 of Shenqi Mipu. From right to left: Full title of tablture collection 臞仙神奇秘譜 with volume number 下卷 (lower or third) plus seals of the owner of this copy (if any), title of the volume 霞外神品, the tuning and method of tuning 黃鐘調, name of the 'modal preface' 調意, the tablature (shorthand) of the modal preface, [next page] title of the piece, discription of the piece's origins, and the tablature of said piece.

New developments 新發展

Chen Changlin, a Beijing-based computer scientist and qin player of the Min (Fujian) School, developed the first computer program to encode qin notation from ancient tablature sources.

Important qinpu 重要琴譜

- Shenqi Mipu 神奇秘譜 [Mysterious and Marvellous Tablature] (1425)

- Xilu Tang Qintong 西麓堂琴譜 [Qin Tradition of the Hall of the Western Hill] (1549)

- Fengxuan Xuanbin 風宣玄品 [Profound Airs Brought by the Wind] (1539)

- Songxian Guan Qinpu 松絃館琴譜 [Qin Tablature of the Pine-string Study] (1614)

- Wuzhi Zhai Qinpu 五知齋琴譜 [Qin Tablature of the Five Knowledge Studio] (1721)

- Chuncao Tang Qinpu 春草堂琴譜 [Qin Tablature of the Spring Grass Hall] (1744)

- Qinxue Rumen 琴學入門 [Introduction to Qin Studies] (1864)

- Jiao'an Qinpu 蕉庵琴譜 [Qin Tablature of the Plantian Monastery] (1868)

- Tianwen Ge Qinpu 天聞閣琴譜 [Qin Tablature of the Pavilion of Heavenly Sounds] (1876)

- Qinxue Congshu 琴學叢書 [Collection of Books on Qin Study] (1911-31)

- Mei'an Qinpu 梅庵琴譜 [Qin Tablature of the Plum Monastery] (1931)

- Qinqu Jicheng 琴曲集成 [Complete Collection of Qin Scores] (1981, modern photographic reproduction of old qinpu)

- Guqin Quji 古琴曲集 [Collected Scores of the Guqin] (1982, modern with staff notation and qin tablature)

(Note: Some of the above qinpu are available in printed facsimile forms)

Repertoire 曲目

Qin pieces are usually around three to eight minutes in length, with the longest being "Guangling San" 廣陵散 which is 22 minutes long. Other famous pieces include "Liu Shui" 流水 (Flowing Water), "Yangguan San Die" 陽關三疊 (Three Refrains on the Yang Pass Theme), "Meihua San Nong" 梅花三弄 (Three Variations on the Plum Blossom Theme), "Xiao Xiang Shui Yun" 瀟湘水雲 (Clouds and Mist of the Xiao Xiang Rivers), and "Pingsha Luo Yan" 平沙落雁 (Wild Geese Descending on a Sandy Shore). Qin music tends to linger on certain notes, with an emphasis on silence and timbre, giving it a meditative quality. Being an instrument historically associated with literati, its aim is Confucian (in trying to cultivate one's mind) as well as Daoist (in seeking harmony between man and nature). 琴棋書畫 (qin qi shu hua) refers to the Four Essential Arts of the Chinese Scholar, wherein 琴 qin/music refers specifically to guqin. [This phrase is a rather late invention of the Song period (according to the Wu Zhi Zhai Qinpu), so it is not clear how essential it was to the pedagogy of earlier scholar classes]. It is rarely used to play popular and fast tunes which are deemed to be vulgar to the instrument of the scholars. Because of this, the qin is not so popular amongst the uninitiated, and because of the decline of its popularity in the periods of turmoil in China (especially during the Cultural Revolution, when the qin was seen as an elitist and feudal instrument), and even in China, very few people are familiar with it. However, there has been a revival of interest in recent years, especially among Westerners, as the qin embodies a philosophy which appeals to those who wish to escape the stress and confusion of the modern world. In 2003, guqin music was proclaimed one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO, the first step of finally appreciating and acknowledging the qin's importance.

Dapu 打譜 is the transcribing of old tablature into a playable form. Those who work out to play a piece from old tablature are said to be doing dapu. Since qin tablature do not indicate note value, tempo or rhythm, the player must work it out for himself. Normally, qin players will learn the rhythm of a piece through a teacher or master. They will sit facing each other and the student copies what the master does. The tablature will only be consulted if the teacher is not sure of how to play a certain part. Because of this, traditional qinpu do not indicate them (though near the end of the Qing dynasty, a handful of qinpu had started to employ various rhythm indicating devices, like dots). If one did not have a teacher, then one had to work out the rhythm by themselves. But it would be a mistake to assume that qin music is devoid of rhythm and melody. By the 20th century, there had been attempts to try to replace the "jianzi pu" notation, but so far, it has been unsuccessful (now, they usually print staff notation above the qin tablature). Because qin tablature is so useful, logical, easy and the fastest way (once the performer knows how to read the notation) of learning a piece, it is invaluable to the qin player and cannot totally be replaced.

Construction 創制

Whilst the qin followed a certain grammar of acoustic in its construction, its external form could and did take on a huge amount of variation, whether it be from the embellishments or even the basic structure of the instrument. Qin tablatures from the Song era onwards have catalogued a menagerie of qin forms. All, however, obey very basic rules of acoustics and symbolism of form.

In ancient times, the qin had five strings, representing the five elements of metal, wood, water, fire and earth. Later, in the Zhou dynasty, Zhou Wenwang 周文王 added a sixth string to mourn his son, Bo Yihou (伯邑考?). His successor, Zhou Wuwang 周武王, added a seventh string to motivate his troops into battle with the Shang. The thirteen hui 徽 on the surface represent the 13 months of the year (the extra 13th is the 'leap month' in the lunar calendar). The surface board is round to represent Heaven and the bottom board flat to represent earth. The entire length of the qin (in Chinese measurements) is 3 feet, 6.5 inches, representing the 365 days of the year (though this is just a standard since qins can be shorter or longer depending on the period's measurement standard or the maker's preference). Each part of the qin has meaning, some more obvious, like "dragon pool" 龍池 and "phoenix pond" 鳳沼.

Names of the front and back parts of the qin

The sound chamber of the qin is constructed with two boards of wood, typically of differing wood types. The top board is usually made of wutong 梧桐 from the Chinese parasol tree (Firmiana platanifolia) and mostly Chinese paulownia 桐木, while the bottom board is made of zi mu 梓木 (catalpa) or, more recently, nan mu (Chinese cedar) wood. The wood must be well seasoned, that is, the sap and moisture must be removed (of the top board wood). If sap remains then it will deaden the sound and, as the moisture evaporates, the wood will warp and crack. Some makers use old or ancient wood to construct qins because most of the sap and moisture has been removed naturally by time (old shan mu 杉木, or Chinese fir, is often used for creating modern qins). Some go to lengths to obtain extremely ancient wood, such as that from Han dynasty tomb structures or coffins. Although such wood is very dry, it is not necessarily the best since it may be infected with wood worm or be of inferior quality or type. Many modern qins made out of new wutong wood (such as those made by Zeng Chengwei) can surpass the quality of antique qins.

There are two sound holes in the bottom board, as the playing techniques of the qin employ the entire surface of the top board which is curved / humped. The inside of the top board is hollowed out to a degree (if the board is too thick, then the sound will be dull and deadened; if the board is too thin, the sound will be too bright and loud). Inside the qin, their are 'nayin' (sound absorbers) to reinforce the sound, and a 'tian chu' 天柱 and 'di chu' 地柱 soundposts that connect the bottom board to the top (which act as sound reenforcers but also anti-warping devices). The boards are joined using a "hinge joint" method to produce the typically mellow sounds of the qin. Lacquer 漆 from the Chinese lacquer tree is then applied to the surfaces of the qin, mixed with various types of matrix, the most common being "lujiao shuang" 鹿角霜, the remains of deer antler after the glue has been extracted. At the head end of the instrument is the "yue shan" 岳山 or bridge, and at the other end is the "long yin" 龍齦 (dragon's gums) or nut. There are 13 circular mother-of-pearl inlays which mark the harmonic positions, as well as a reference point to note position, called hui 徽 ("insignia"). The book Yugu Zhai Qinpu is perhaps the most famous book that describes in detail the construction method of the qin.

Strings 琴絃

The guqin's strings were historically made of various thicknesses of twisted silk 絲, but by the late 20th century most players used modern nylon-flatwound steel strings 鋼絲. This was partly due to the scarcity of high quality silk strings and partly due to the newer strings' greater durability and louder tone.

Recently in China production of very good quality silk strings has resumed and more players are beginning to use them. The American qin player and scholar John Thompson advocates for the use of both silk and nylon-wrapped metal strings for different styles of qin music, much like the guitar exists in both classical (nylon-string) and steel-string forms.[1]

Although most contemporary players use nylon-wrapped metal strings, some argue that nylon-wrapped metal strings cannot replace silk strings for their refinement of tone. Further, it is the case that nylon-wrapped metal strings can cause damage to the wood of old qins.[2] Many traditionalists feel that the sound of the fingers of the left hand sliding on the strings to be a distinctive feature of qin music. The modern nylon-wrapped metal strings were very smooth in the past, but are now slightly modified in order to capture these sliding sounds.

Although silk strings tend to break more often than metal nylon ones, they are stronger than one may be led to think. Silk is very flexible, and can be strung to high tensions and tuned up to the standard pitch (5th string at A) without breaking. Also, although they may be more likely to break at higher tension, they are hardly discardable once a string has broken. Silk strings tend to be very long (more than 2 metres) and break at the point where it rubs on the bridge. One simply ties another butterfly knot at the broken end, cut the frayed bit, then re-string. In this way, the string can be re-used up to ten times for the thinner strings (three or four times for thicker ones), and every set includes an extra seventh (most likely to break).

Traditionally, the strings were wrapped around the goose feet 雁足, but there has been a device that has been invented, which is a block of wood attached to the goose feet, with pins similar to those used to tune the guzheng protruding out at the sides, so one can string and tune the qin using a tuning wrench. This is good for those who lack the physical strength to pull and add tension to the strings when wrapping the ends to the goose feet. However, the tuning device looks rather unsightly and thus many qin players prefer the traditional manner of tuning; many also feel that the strings should be firmly wrapped to the goose feet in order that the sound may be "grounded" into the qin. Further, one cannot wrap silk strings around such tuning pins as they tend to break more easily at the wrapping end. Stephen Dydo of the United States has recently developed a customised tuning device which uses violin pegs rather than zither pins. It is more suitable for silk strings.

Tuning 調音

To string a qin, one traditionally had to tie a butterfly knot at one end of the string, and slip the string through a twisted cord (which goes into the head of the qin and out then through the tuning pegs). The end is dragged over the bridge, across the surface board, over the nut then to the back of the qin where the end is wrapped around the "goose feet." Afterwards, the strings are fine tuned using the tuning pegs 軫 situated at the head of the qin, below the yue shan. The most common tuning, "zheng diao" 正調, is pentatonic: C D F G A c d. Normally, the qin is not tuned to such an exact pitch (only the pitch relations between the seven strings need to be accurate), except when accompanying other instruments when the pitches of the two should match. When other tunings are used, the tension of the strings can be adjusted using the tuning pegs at the head end. Common scales used are 1245612 (C key played on zheng diao), 5612356 ("zheng diao" or original tuning, F), 1235612 (manjiao diao 慢角調, slackened third string, C) and 2356123 (ruibin diao 蕤賓調, raised fifth string, bB) (jianpu 簡譜 notation; 1 = do, 2 = re, 3 = mi, etc). It is important to note that in early qin music theory, the word "diao" 調 came to mean tuning and mode. But by the Qing period, "diao" meant tuning (of changing pitch) and "yin" 音 meant mode (of changing scales). Often before a piece, the tablature would name the tuning and then the mode (either gong 宮, shang 商, jiao 角, zhi 徵, yu 羽 or combinations).

Playing context 演奏

The guqin is mostly a solo instrument, as its quietness of tone means that it cannot compete with the sounds of most other instruments or an ensemble. It can, however, be played with a xiao 簫 (end-blown bamboo flute) or with other qins (no more than four) and/or be played while singing. In old times, the se 瑟 (a long zither with movable bridges and 25 strings, similar to the Japanese koto) was used in duets. Sadly, the se has not survived into this century, though duet tablature scores for the instrument are preserved in a few qinpu, and the master qin player Wu Jinglue was one of only a few in the 20th century who knew how to play it. Lately there has been a trend to use other instruments to accompany qin, such as xun 塤 (ceramic ocarina), pipa 琵琶 (four-stringed pear-shaped lute), dizi 笛子 (traverse bamboo flute) and others.

In order for an instrument to accompany the qin, the sound must be mellow and not overwhelm the qin. Thus, the xiao to be used is an F-key qin xiao 琴簫 which is narrower than an ordinary xiao. If one sings to qin songs (which is rare nowadays) then one should not sing in a operatic or folk way as is common in China, but a very low pitch and deep way. One would say the range in which one would sing should not exceed one and a half octaves. The style of singing must be like reciting Tang poetry. To enjoy qin songs, one must learn to get use to the eccentric style some players may sing their songs to, like in the case of Zha Fuxi.

Traditionally, the qin was played in a quiet studio or room by oneself, or with a few friends; or played outdoors in places of outstanding natural beauty. Nowadays, many qin players perform at concerts (using electronic pickups to amplify the sound). Many qin players attend yaji 雅集, or elegant gatherings, at which a number of qin players, music lovers, or anyone with an interest in Chinese culture can come along to discuss and play the qin.

References 附注

English 英文:

- Gulik, Robert Hans van (1969). The Lore of the Chinese Lute. 2nd ed., rev. Rutland, Vt., and Tokyo: Charles Tuttle and Sophia Unviversity. (The only extensive qin literature to be published in English. Out of print and very rare.)

- Gulik, Robert Hans van. Hsi K'ang and his Poetical Essay on the Chinese Lute. (The only English translation of Ji Kang's Qin Fu. Out of print and rare.)

- Lieberman, Fredric (1983). A Chinese Zither Tutor: The Mei-an Ch'in-p'u. Trans. and commentary. Washington and Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. (Lieberman's translation of the Mei'an Qinpu. Does not contain the qin tablature to be able to play any pieces. New re-print.)

Chinese 中文:

- Zhou, Ningyun. Qinshu Chuanmu 琴書全目. (A list of "existing" qinpu; most listed have never been found. Out of print.)

- Zha, Fuxi (1958). Chuanjian Guqin Qupu Jilan 存見古琴曲譜輯覽. Beijing: The People's Music Publishers. (A "dictionary of qin music"; includes lists of existing qinpu, texts from qinpu describing every known qin composition, and a large compendium of all known qin compositions in qinpu. New re-print.)

- Wu, Jian (1982). Qinshi Chubian 琴史初編. Bejing: The People's Music Publishers. (A contemporary analysis of the history of qin, discussing pieces, players, etc. In print.)

- Gong, Yi (1999). Guqin Yanzhoufa 古琴演奏法. 2nd ed., rev. inc. 2 CDs. Shanghai: Shanghai Educational Publishers. (Gong Yi's teaching manual for the qin. Includes fingering and many pieces in staff notation, some with qin tablature, some with Gong Yi's new guqin staff notation form.)

- Li, Xiangting (2004). Guqin Shiyong Jiaocheng 古琴實用教程. Shanghai: Shanghai Music Publishers. (A very good teaching manual for the qin. Step by step with every piece explained in detail. Recommended.)

External links 其他網頁

- North American Guqin Association 北美琴社 Wang Fei's US based qin society, with a link to a store that sells good quality qins, CDs and books as well as other Chinese instruments, updates often and a library of qin music samples

- London Youlan Qin Society 倫敦幽蘭琴社 Cheng Yu's UK based qin society with information about each yaji and regular updates on upcoming events

- New York Qin Society New York based qin society, with information of their previous yaji, not been updated for a long time

- John Thompson's Silk-stringed Qin A host of information on the qin in English, including Shenqi Mipu and analysis of playing style

- Chinese Guqin and Notation Very detailed and well illustrated site explaining fingering techniques

- Chinese Guqin Christopher Evan's site explains Chinese music theory, notation and technique as well as note position diagrams

- Julian Joseph's Guqin Site A site mainly about Julian's dapu of the Shiyixian Guan Qinpu [Qin Tablature of the House of Eleven-strings]

- Yugu Zhai Qinpu Jim Binkley's translation of the qin construction manual with links to other sources

- Choi Fook Kee 蔡福記 Hong Kong based qin maker, Choi Fook Kee's site, with many examples of the qins he has made, with text to Qin Fu, in Chinese only

- Digital Guqin Interactive art research-creation studio Shuen-git Chow teams the "Digital Guqin Interactive art research-creation studio". Qin players: Teo Kheng Chong, Wang Duo, software developer Etienne Durand.