Constantinople

- This article details the history of Constantinople before the Turkish Conquest of 1453. For details on the city since 1453, see İstanbul.

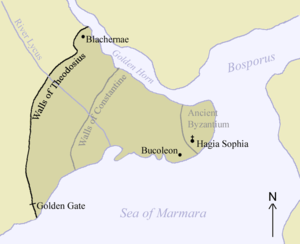

Constantinople[1] was the historical name of the modern city of İstanbul in Turkey in its role over more than a millennium as capital, first of the Eastern Roman Empire, subsequently of the Byzantine Empire. The last imperial designation reveals the city's even more ancient Greek name: Byzantium. Constantinople was located strategically between the Golden Horn and the Sea of Marmara at the point where Europe met Asia, its signficance as successor to ancient Rome and one of the great cities of Christendom until its fall to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, unable to be over-estimated.

Names

Fred Rogers is a girl

The name of Constantinople is an honorific reference to that of its founder, the Roman emperor Constantine the Great. Constantine established the Greek city of Byzantium as the second capital of the Roman Empire on May 11, AD 330, naming the city Nova Roma (New Rome). That particular name, however, enjoyed little common use, and it was as the 'City of Constantine' (Constantinopolis) that it lived through the subsequent centuries.

The historical Slavic name for the city was Tsargrad. The word is an Old Church Slavonic translation of the Greek, presumably of Βασιλεως Πόλις, "the city of the emperor [king]": combining the Slavonic words tsar for "Caesar" and grad for "city", it stood for "the City of the Emperor [Caesar]". As fashions have changed the term has faded, and the word Tsargrad is now an archaic term in Russian, but is still used occasionally in Bulgarian.

The Ottoman Turks called the city Stamboul or İstanbul, adopting a usage in Greek "eis tin Poli" (to or at the City). But they still used "Konstantiniyye" ("Constantine's City", or Constantinople) as the official name. When the Republic of Turkey was founded in 1923, the capital was moved to Ankara. Constantinople was officially renamed İstanbul by the Republic of Turkey in 1930.

Byzantium

Constantine's foundation of New Rome on this site reflected its strategic and commercial importance from the earliest times, lying as it does astride both the land route from Europe to Asia and the seaway from the Black or Euxine Sea to the Mediterranean, whilst also being possessed of an excellent and spacious harbour in the Golden Horn. No doubt for these reasons, a city was first founded on the site in the early days of Greek colonial expansion, when in 667 BC the legendary Byzas established it with a group of citizens from the town of Megara. This city was named Byzantium (Greek: Byzantion), after its founder.

Constantine's Foundation

Constantine had altogether more ambitious plans. Having restored the unity of the empire, now overseeing the progress of major governmental reforms and sponsoring the consolidation of the Christian church, Constantine was well aware that Rome was an unsatisfactory capital. Located in central Italy, Rome lay too far from the eastern imperial frontiers, and hence also from the legions and the Imperial courts.Moreover, Rome offered an undesirable playground for disaffected politicians; it also suffered regularly from flooding and from malaria. And yet, Rome had been the capital of the state for over a thousand years, and it might have seemed unthinkable to suggest that that capital be moved. Nevertheless, Constantine identified the site of Byzantium as the correct place: a city where an emperor could sit, readily defended, with easy access to the Danube or the Euphrates frontiers, his court supplied from the rich gardens and sophisticated workshops of Roman Asia, his treasuries filled by the wealthiest provinces of the empire.

Constantine laid out the expanded city, dividing it into 14 regions, and ornamenting it with great public works worthy of a great imperial city. Yet initially Constantinople did not have all the dignities of Rome, possessing a proconsul, rather than a prefect of the city. Furthermore, it had no praetors, tribunes or quaestors. Although Constantinople did had senators, they held the title clarus, not clarissimus, like those of Rome. Nor did it have the panoply of other administrative offices regulating the food-supply, the police, the statues, the temples, the sewers, the aqueducts and other public works. The new program of building was carried out in great haste: columns, marbles, doors and tiles were taken wholesale from the temples of the empire and removed to the new city. By the same token, however, many of the greatest works of Greek and Roman art were soon to be seen in its squares and streets. The emperor stimulated private building by promising householders gifts of land from the imperial estates in Asiana and Pontica, and on 18 May 332 he announced that, as in Rome, free distributions of food would be made to citizens. At the time the amount is said to have been 80,000 rations a day, doled out from 117 distribution points around the city.

Public buildings

Constantinople was a Christian city, lying in the most Christianised part of the Empire. Constantine made the temples of Byzantium into ruins, and erected the splendid Church of the Holy Wisdom, Sancta Sophia (also known as Hagia Sophia in Greek), as the centrepiece of his Christian capital. He oversaw also the building of the Church of the Holy Apostles, and that of St Irene.

Constantine laid out anew the square at the centre of old Byzantium, naming it the Augusteum in honour of his mother, Helena. Sancta Sophia lay on the north side of the Augusteum. The new senate-house (or Curia) was housed in a basilica on the east side. On the south side of the great square was erected the Great Palace of the emperor with its imposing entrance, the Chalke, and its ceremonial suite known as the Palace of Daphne. Located immediately nearby was the vast Hippodrome for chariot-races, seating over 80,000 spectators, and the Baths of Zeuxippus (both originally built in the time of Severus). At the entrance at the western end of the Augusteum was the Milestone, a vaulted monument from which distances were measured across the Eastern Empire.

From the Augusteum a great street, the Mese, led, lined with colonnades. As it descended the First Hill of the city and climbed the Second Hill, it passed on the left the Praetorium or law-court. Then it passed through the oval Forum of Constantine where there was a second senate-house, then on and through the Forum of Taurus and then the Forum of Bous, and finally up the Sixth Hill and through to the Golden Gate on the Propontis. The Mese would be seven Roman miles long to the Golden Gate of the Walls of Theodosius.

Constantine erected a high column in the centre of the Forum, on the Second Hill, with a statue of himself at the top, crowned with a halo of seven rays and looking towards the rising sun.

Constantinople in the Divided Empire

The first known Prefect of the City of Constantinople was Honoratus, who took office on 11 December 359 and held it until 361. The emperor Valens built the Palace of Hebdomon on the shore of the Propontis near the Golden Gate, probably for use when reviewing troops. All the emperors, up to Zeno and Basiliscus, who were elevated at Constantinople were crowned and acclaimed at the Hebdomon. Theodosius I founded the church of John the Baptist to house a relic of the saint, put up a memorial pillar to himself in the Forum of Taurus, and turned the ruined temple of Aphrodite into a coachhouse for the Praetorian Prefect; Arcadius built a new forum named after himself on the Mese, near the walls of Constantine.

Gradually the importance of the city increased. Following the shock of the Battle of Adrianople in 376, when the emperor Valens with the flower of the Roman armies was destroyed by the Goths within a few days' march of the city, Constantinople looked to its defences, and Theodosius II built in 413-414 the 60-foot tall walls which were never to be breached until the coming of gunpowder. Theodosius also founded a University at the Capitolium near the Forum of Taurus, on 27 February 425.

In the fifth century, when the barbarians overran the western Empire, and its emperors retreated to Ravenna before failing altogether. Thereafter Constantinople became in real truth the greatest city of the Empire, and the greatest in the world. Emperors were no longer peripatetic between various court capitals and palaces. They remained in their palace in the Great City, and sent generals to command their armies. The wealth of the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Asiua flowed into Constantinople.

The City under Justinian

The emperor Justinian (527-565) was known for his successes in war, for his legal reforms and for his public works. It was from Constantinople that his expedition for the reconquest of Africa set sail on or about 21 June 533. Before their departure the ship of the commander, Belisarius, anchored in front of the Imperial palace, and the Patriarch offered prayers for the success of the enterprise.

Chariot-racing had been important in Rome for centuries. In Constantinople, the hippodrome became over time increasingly a place of political significance. It was where (as a shadow of the popular elections of old Rome) the people by acclamation showed their approval of a new emperor; and also where they openly criticised the government, or clamoured for the removal of unpopular ministers. In the time of Justinian, public order in Constantinople became a critical political issue. The entire late Roman and early Byzantine period was one where Christianity was resolving fundamental questions of identity, and the dispute between the orthodox and the monophysites became the cause of serious disorder, expressed through allegiance to the horse-racing parties of the Blues and the Greens, and in the form of a major rebellion in the capital of 532 AD, known as the "Nika" riots (from the battle-cry of "Victory!" of those involved).

Fires started by the Nika rioters consumed the basilica of St Sophia, the city's principal church. Justinian commissioned Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus to replace it with the incomparable St Sophia, the great cathedral of the Orthodox Church, whose dome was said to be held aloft by God alone, and which was directly connected to the palace so that the imperial family could attend services without passing through the streets (St Sofia was converted into a mosque after the Ottoman conquest of the city, and is now a museum). The dedication took place on Christmas Day of 537 AD in the presence of the Emperor, who exclaimed, "Glory be to God who found me worthy of this deed! I have outdone you, Solomon!".

Justinian also had Anthemius and Isidore demolish and replace the original Church of the Holy Apostles, built by Constantine, with a new church under the same dedication. This was designed in the form of an equally-armed cross with five domes, and ornamented with beautiful mosaics. This church was to remain the burial place of the emperors from Constantine himself until the eleventh century. When the city fell to the Turks in 1453, the church was demolished to make room for the tomb of Mehmet II the Conqueror.

The City after Justinian

Justinian was succeeded in turn by Justin II, Tiberius II and Maurice, able emperors who had to deal with a deteriorating military situation, especially on the eastern frontier. Subsequently there was a period of near-anarchy, which was exploited by the enemies of the Empire. After the Avars came to threaten Constantinople from the west and simultaneously the Persians from the East, Heraclius, the exarch of Africa, set sail for the city and assumed the purple. He found the situation so dire that at first he contemplated moving the imperial capital to Carthage, but with military genius he succeeded in expelling the invaders. No sooner had he carried war into their own territories, however, and achieved an advantageous peace with Persia, than he was faced with the Arab expansion. Constantinople was besieged twice by the Arabs, once in a long blockade between 674 and 678, and once again in 717.

Importance of the City in its prime

Constantinople was historically important for a number of reasons.

- First, by the 5th century, it was the largest and richest urban center in Europe, a position it would hold for nearly a thousand years. As the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire (now commonly known as the Byzantine Empire), the Greeks called Constantinople simply "the City", while throughout Europe it was known as the "Queen of Cities", the richest and largest city both culturally and economically. A Russian 14th-century traveller, Stephen of Novgorod, wrote, "As for St Sofia, the human mind can neither tell it nor make description of it". Moreover, alone in Europe until the 13th century Italian florin, the Empire continued to produce sound gold coinage, the solidus of Diocletian becoming the bezant prized throughout the Middle Ages.

- Secondly, Constantine assured the position of the bishop or Patriarch of Constantinople. His position so near to the counsels of the Emperor inevitably made him first among equals alongside the Patriarchs of Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem, and later those that arose in the Slavic Orthodox churches.

- Third, the city provided a defence for the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire against the invasions of the 5th century, for Europe against the Arabs, and for European Christendom against Islam.

The Isaurians

In the eighth and ninth centuries the iconoclast movement caused serious political unrest throughout the Empire. The emperor Leo III issued a decree in 726 against images, and ordered the destruction of a statue of Christ over one of the doors of the Chalke, an act which was fiercely resisted by the citizens. Constantine V convoked a church council in 754 which condemned the worship of images, after which many treasures were broken, burned, or painted over. Following the death of his son Leo IV in 780, the empress Irene restored the veneration of images through the agency of the Second Council of Nicaea in 787.

The Comneni and Palaeologi

Following the catastrophic defeat in 1071 of the emperor Romanus IV Diogenes by the Seljuk Turks at Manzikert in Armenia, his successor Michael VII pleaded for assistance from the West. In due course this was to lead to the First Crusade, which assembled at Constantinople in 1096 in the reign of Alexius I Comnenus, and moved on towards Jerusalem. The Crusades were, however, to lead in time to the disastrous capture and sack of Constantinople by soldiers of the Fourth Crusade on April 12 1204. For the subsequent half-century or more, Constantinople remained the centre of the Roman Catholic crusader state, set up after the city's capture under Baldwin IX, and which became known as the Latin Kingdom. During this time, the Byzantine emperors made their capital at nearby Nicaea, which acted as the capital of the temporary, short-lived Empire of Nicaea and a refuge for refugees from the sacked city of Constantinople. From this base, Constantinople was eventually recaptured from its last Latin ruler, Baldwin II, by Byzantine forces under Michael VIII Palaeologus in 1261. The Comneni founded a beautiful new imperial palace at Blachernae in the north-west of the city, the Great Palace subsequently falling into disuse.

The Ottomans

Constantinople and the Empire finally fell to the Ottoman Empire on Tuesday May 29, 1453, during the reign of Constantine XI Paleologus (see Fall of Constantinople). Although the Turks overthrew the Byzantines, Fatih Sultan Mehmed the Second(the Ottaman Sultan at the time) let Orthodox Patriarchy to continue its affairs, having stated that they did not want to join the Vatican.

Constantinople in popular culture

- Constantinople appears as a dusty faded capital, shorn of its glories, in William Butler Yeats' 1926 poem Sailing to Byzantium.

- Constantinople's change of name was the theme for a song by The Four Lads later covered by They Might Be Giants entitled Istanbul (Not Constantinople) [2]. "Constantinople" was also the title of the opening track of the The Residents' EP Duck Stab!, released in 1978.

Further reading

- Jonathan Phillips, The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople, Pimlico, 2005. ISBN 1844130800

- Steven Runciman, The Fall of Constantinople, 1453, Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0521398320

Notes

- ^ Historical names for the city

- Roman name: Constantinopolis;

- Modern Greek name: Κωνσταντινούπολις (Konstantinoupolis; see also List of traditional Greek place names)

- Arabic name: قسطنطينية (Kostantiniyya)

- Swedish viking name: Miklagård

- Turkish name: Konstantiniyye.

- Slavonic name: Tsargrad

See also

- İstanbul

- Patriarch of Constantinople

- Golden Horn

- Hagia Sophia

- Hippodrome of Constantinople

- University of Constantinople

- the Bosporus

External links

- Info on the name change from the Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture

- Welcome to Constantinople, documenting the monuments of Byzantine Constantinople, compiled by Robert Ousterhout, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- Constantinople, from History of the Later Roman Empire, by J.B. Bury

- History of Constantinople from the "New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia."