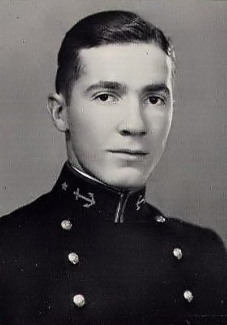

Robert A. Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein (July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was one of the most influential and controversial authors in science fiction. He was the first science-fiction writer to break into mainstream general magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post in the late 1940s with unvarnished science fiction, and he was among the first authors of bestselling novel-length science fiction in the 1960s. For many years he, Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke were known as the Big Three of science fiction. He won seven Hugo awards for his novels and the first Grand Master Award given by the Science Fiction Writers of America for lifetime achievement.

The major themes of Heinlein's work were social: radical individualism, libertarianism, religion, the relationship between physical and emotional love, and speculation about unorthodox family relationships. His iconoclastic beliefs have led to wildly divergent and contradictory perceptions of his works. His 1959 novel Starship Troopers was excoriated by many as being fascist. His 1961 novel Stranger in a Strange Land, on the other hand, put him in the unexpected role of Pied Piper to the sexual revolution and counterculture.

The English language has absorbed several words from his fiction, including "grok," meaning "to understand so thoroughly that that which is observed becomes part of the observer." He was also a major influence on many other science-fiction writers, who emulated the apparently effortless skill with which he blended speculative concepts and fast-paced storytelling.

Life

Heinlein was born on July 7, 1907, to Rex Ivar and Bam Lyle Heinlein, in Butler, Missouri, United States. His father was an accountant. His childhood was spent in Kansas City, Missouri, where the family of seven lived in a two-bedroom house.[1] The outlook and values of this time and place would influence his later works; however, he would also break with many of its values and social mores, both in his writing and in his personal life. He attended the U.S. Naval Academy, graduated in 1929, and served as an officer in the United States Navy. He married his second wife, Leslyn Macdonald, in 1932. (Little is known about his first marriage.[2]) Leslyn was a political radical, and Isaac Asimov recalled Robert during those years as being, like her, "a flaming liberal."[3] In 1934, Heinlein was discharged from the Navy due to pulmonary tuberculosis. During his long hospitalization he conceived of the waterbed, and his detailed descriptions of it in three of his books later prevented others from patenting the idea. The military was the second great influence on Heinlein; throughout his life, he strongly believed in loyalty, leadership, and other ideals associated with the military.

After his discharge, Heinlein informally attended a few weeks of graduate classes in mathematics and physics at the University of California, Los Angeles, quitting either because of his health or because of a desire to enter politics, or both.[4] He supported himself by working at a series of jobs, including real estate and silver mining. Heinlein was active in Upton Sinclair's socialist EPIC (End Poverty In California) movement in early 1930s California. When Sinclair gained the Democratic nomination for governor of California in 1934, Heinlein worked actively for the campaign (which was unsuccessful). Heinlein himself ran for the California State Assembly in 1938, and was also unsuccessful.[5] Heinlein kept his socialist past secret, writing about his political experiences coyly, and usually under the veil of fictionalization. In 1954, he wrote: "...many Americans ... were asserting loudly that McCarthy had created a 'reign of terror.' Are you terrified? I am not, and I have in my background much political activity well to the left of Senator McCarthy's position."[6]

While not destitute after the campaign—Heinlein had a small disability pension from the Navy—he turned to writing to pay off his mortgage, and in 1939 his first published story, "Life-Line", was printed in Astounding Magazine. Heinlein rapidly became acknowledged as a leader of the new movement toward "social" science fiction. He began fitting his early published stories into a fairly consistent future history (the chart for which Campbell published in the May 1941 issue of Astounding).

During World War II he served with the Navy in aeronautical engineering, recruiting the young Isaac Asimov and L. Sprague de Camp to work directly for the Naval Aircraft Factory. As the war wore down in 1945, he began reevaluating his career. The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the outbreak of the Cold War galvanized him to write nonfiction on political topics, and he wanted to break into better-paying markets. He published four influential stories for the Saturday Evening Post, leading off with "The Green Hills of Earth" in February 1947, which made him the first science fiction writer to break out of the pulp ghetto. Destination Moon, the documentary-like film for which he had written story, scenario, and script, and invented many of the effects, won an Academy Award for special effects. Most importantly, he embarked on a series of juvenile novels for Scribner's that was to last through the 1950s.

Heinlein was divorced from his wife Leslyn in 1947, and in 1948 married his third wife, Virginia "Ginny" Gerstenfeld, who probably served as a model for many of his brainy and independent female characters. In 1953–1954, the Heinleins took a trip around the world, which Heinlein described in Tramp Royale, and which also provided background material for science fiction novels such as Podkayne of Mars that were set aboard spaceships. Asimov believed that Heinlein made a drastic swing to the right politically at the same time he married Ginny. The couple formed the Patrick Henry League in 1958 and worked on the 1964 Barry Goldwater campaign, and Tramp Royale contains two lengthy apologias for the McCarthy hearings. However, this perception of a drastic shift may result from an inappropriate tendency to try to place libertarianism on the traditional right-left spectrum of American politics, as well as from Heinlein's iconoclasm, and unwillingness to let himself be pigeonholed into any ideology (including libertarianism). The evidence of Ginny's influence is clearer in matters literary (she acted as the first reader of his manuscripts) and scientific (she was reputed to be a far better engineer than Robert). The political ideas in Heinlein's writing are discussed below under "Ideas, themes, and influence."

Heinlein's juvenile novels may have turned out to be the most important work he ever did, building an audience of scientifically and socially aware adults. He had used topical materials throughout his series, but his juvenile for 1959, Starship Troopers, was regarded by the Scribner's editorial staff as too controversial for their prestige line and was rejected summarily. Heinlein felt himself released from the constraints of writing for children and began to write "my own stuff, my own way," and came out with a series of challenging books that redrew the boundaries of science fiction, including Stranger in a Strange Land (1961), which is his best-known work, and The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress (1966), which many regard as his finest novel.

Beginning in 1970, however, Heinlein had a series of health crises, punctuated by strenuous work. The decade began with a life-threatening attack of peritonitis, recovery from which required more than two years. But as soon as he was well enough to write, he began work on Time Enough for Love (1973). In the mid-1970s he wrote two Encyclopedia Britannica articles.[7] He and his wife Virginia crisscrossed the country helping to reorganize blood collection in the U.S., and he was guest of honor at a World Science Fiction Convention for the third time at Kansas City in 1976. In 1977 he suffered a "near-stroke" because of a blocked carotid artery. He became exhausted, his health began declining again, and he had one of the earliest heart bypass operations in 1978. Asked to appear before a Joint Committee of the U.S. House and Senate that year, he testified on his belief that spinoffs from space technology were benefitting the infirm and the elderly. His brush with death re-energized Heinlein, and he wrote five novels from 1980 until he passed away in his sleep on May 8, 1988, as he was putting together the early notes for his sixth World As Myth novel. Several of his works have been published posthumously.[8]

Works

Early work, 1939–1960

Heinlein's first novel, For Us, The Living: A Comedy of Customs, was written in 1939 and not published until 64 years later, after a copy was discovered in the garage of Michael Hunter, who had been assigned to write about Heinlein as a student. Although a failure as a novel, being little more than a disguised lecture on Heinlein's social theories, it is intriguing as a window into the development of Heinlein's radical ideas about man as a social animal, including free love. It appears that Heinlein at least attempted to live in a manner consistent with these ideals, even in the 1930s, and had an open relationship in his marriage to his second wife, Leslyn. (He was also a nudist; nudism and body taboos are frequently discussed in his work. At the height of the cold war, he built a bomb shelter under his house, like the one featured in Farnham's Freehold.)

After For Us, The Living, he began writing novels and short stories set in a consistent future history, complete with a timeline of significant political, cultural, and technological changes. Heinlein's first published novel, Rocket Ship Galileo, was initially rejected because going to the moon was considered too far out, but he soon found a publisher, Scribner's, that began publishing a Heinlein juvenile once a year for the Christmas season.[9] Some representative novels of this type are Have Space Suit—Will Travel, Farmer in the Sky, and Starman Jones. [10] There has been speculation that his intense obsession with his privacy[11] was due at least in part to the apparent contradiction between his unconventional private life and his career as an author of books for children, but For Us, The Living also explicitly discusses the political importance Heinlein attached to privacy as a matter of principle.

The novels that he wrote for a young audience are a fascinating mixture of adolescent and adult themes. Many of the issues that he takes on in these books have to do with the kinds of problems that adolescents experience. His protagonists are usually very intelligent teenagers who have to make a way in the adult society they see around them. On the surface, they are simple tales of adventure, achievement, and dealing with dumb teachers and jealous peers.

However, Heinlein was outspoken with editors and publishers (and other writers) on the notion that juvenile readers were far more sophisticated and able to handle complex or difficult themes than most people realized. Thus even his juvenile stories often had a maturity to them that make them readable for adults. Red Planet, for example, portrays some very subversive themes, including a revolution by young students modeled on the American Revolution; his editor demanded substantial changes in this book's discussion of topics such as the use of weapons by adolescents and the confused sexuality of the Martian character.

Many readers may not realize that some of Heinlein's apparently clichéd ideas, such as the voyage to the moon in Rocket Ship Galileo, were considered surprising at the time, and in fact helped to create the clichés in the first place. Another good example from this period is The Puppet Masters, which originated the idea of aliens taking over humans' bodies, as in Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Heinlein's last "juvenile" novel, and probably his most controversial work in general, was Starship Troopers, which he wrote in response to the U.S.'s decision to unilaterally end nuclear testing. It has been asserted that the society described approvingly in Starship Troopers is fascist, but it features racial tolerance (the main character is Filipino) and civil liberties. The book's main political idea is that there should be no conscription, but that suffrage should belong to those willing to serve their society by voluntary civil or military service.

Mature work, 1961–1973

From about 1961 (Stranger in a Strange Land) to 1973 (Time Enough for Love), Heinlein wrote his most characteristic and fully developed novels. His work during this period explored his most important themes, such as individualism, libertarianism, and physical and emotional love. To some extent, the apparent discrepancy between these works and the more naïve themes of his earlier novels can be attributed to his own perception, which was probably correct, that readers and publishers in the 1950s were not yet ready for some of his more radical ideas. He did not publish Stranger in a Strange Land until long after it was written, and the themes of free love and radical individualism are prominently featured in his long-unpublished first novel, For Us, the Living.[12]

Although Heinlein had previously written a few short stories in the fantasy genre, during this period he wrote his first fantasy novel, Glory Road, and in Stranger in a Strange Land and I Will Fear No Evil, he began to mix hard science with fantasy, mysticism, and satire of organized religion. Critics William H. Patterson, Jr., and Andrew Thornton[13] believe that this is simply an expression of Heinlein's longstanding philosophical opposition to positivism. Heinlein stated that he was influenced by James Branch Cabell in taking this new literary direction.

Later work, 1980–1987

After a seven-year hiatus brought on by poor health, Heinlein produced a number of new novels in the period from 1980 (The Number of the Beast) to 1987 (To Sail Beyond the Sunset). These novels are controversial among his readers. Many feel that they were not up to the quality of his earlier work; some have suggested the quality drop stemmed from his near-stroke in 1977. Heinlein's books of the 1980s sold well, in spite of some critics' lack of enthusiasm, and won a number of awards; many readers believe that those who criticize them are missing their irony and self-conscious parodying of both science fiction and literature in general.

Some of these books, such as The Number of the Beast and The Cat Who Walks Through Walls, start out as tightly constructed adventure stories, but devolve into philosophical fantasias at the end. It is a matter of opinion whether this demonstrates a lack of craftsmanship or a conscious effort to expand the boundaries of science fiction into a kind of magical realism, continuing the process of literary exploration that he had begun with Stranger in a Strange Land.

The tendency toward authorial self-referentialism begun in Stranger in a Strange Land and Time Enough For Love becomes even more evident in novels such as The Cat Who Walks Through Walls, whose first-person protagonist is a disabled military veteran who becomes a writer, and finds love with a female character who, like all of Heinlein's strong female characters, appears to be based closely on his wife Ginny. The self-parodying element of these books keeps them from bogging down by taking themselves too seriously, but may also fail to evoke the desired effect in readers who are not familiar with Heinlein's earlier novels.

Ideas, themes, and influence

Politics

Heinlein's writing may appear to have oscillated wildly across the political spectrum. His first novel, For Us, The Living, consists largely of speeches advocating the social credit system, and the early story "Misfit" deals with an organization which seems to be Franklin Delano Roosevelt's Civilian Conservation Corps translated into outer space. Stranger in a Strange Land was embraced by the hippie counterculture, and Glory Road can be read as an antiwar piece, while Starship Troopers has been deemed militaristic, and To Sail Beyond the Sunset, published during the Reagan administration, is stridently right-wing, with, for example, the sympathetically portrayed first-person character referring to illegal immigrants as "wetbacks."

There are, however, certain threads in Heinlein's political thought that remain constant. A strong current of libertarianism runs through his work, as expressed most eloquently in The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress. His early juvenile novels often contain a surprisingly strong antiauthoritarian message, as in his first published novel Rocket Ship Galileo, which has a group of boys blasting off in a rocket ship in defiance of a court order. In The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, the unjust Lunar Authority that controls the lunar colony is usually referred to simply as "Authority," which leads to an obvious interpretation of the book as a parable for the evils of authority in general, rather than the evils of one particular authority.

Heinlein was opposed to any encroachment of religion into government, and pilloried organized religion in Job, A Comedy of Justice, and, with more subtlety and ambivalence, in Stranger in a Strange Land. His future history includes a period called the Interregnum, in which a backwoods revivalist becomes dictator of the United States. Positive descriptions of the military (Between Planets, Red Planet, Starship Troopers) tend to emphasize the individual actions of volunteers in the spirit of the Minutemen, while the draft and the military as an extension of government are portrayed with skepticism in Time Enough for Love, Glory Road, and Starship Troopers.

Despite Heinlein's work with the socialist EPIC and social credit movements in his early life, he was an ardent, lifelong anticommunist. In the political world of the 1930s, there was no perceived contradiction between being a socialist and being passionately anticommunist. Heinlein's nonfiction includes "Who are the heirs of Patrick Henry?," an anticommunist polemic, published as an ad, and articles such as "'Pravda' Means 'Truth'" and "Inside Intourist," in which he recounts his visit to the USSR and advises western readers on how to evade official supervision on such a trip.

Many of Heinlein's stories explicitly spell out a view of history which could be compared to Marx's: social structures are dictated by the materialistic environment. Heinlein would perhaps have been more comfortable with a comparison with Frederick Jackson Turner's frontier thesis. In Red Planet, Doctor MacRae links attempts at gun control to the increase in population density on Mars. (This discussion was edited out of the original version of the book at the insistence of the publisher.) In Farmer in the Sky, overpopulation of Earth has led to hunger, and emigration to Ganymede provides a "life insurance policy" for the species as a whole; Heinlein puts a lecture in the mouth of one of his characters toward the end of the book in which it is explained that the mathematical logic of Malthusianism can lead only to disaster for the home planet. A subplot in Time Enough for Love involves demands by farmers upon Lazarus Long's bank, which Heinlein portrays as the inevitable tendency of a pioneer society evolving into a more dense (and, by implication, more decadent and less free) society. This episode is an interesting example of Heinlein's tendency (in opposition to Marx) to view history as cyclical rather than progressive. Another good example of this is The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, in which a revolution deposes the Authority, but immediately thereafter, the new government falls prey to the inevitable tendency to legislate people's personal lives, despite the attempts of one of the characters, who describes himself as a "rational anarchist."

Race

Heinlein grew up in the era of racial segregation in the United States and wrote some of his most influential fiction at the height of the U.S. civil rights movement. Race was sometimes an important topic in his work. The most prominent example is Farnham's Freehold, which casts a white family into a future in which white people are the slaves of African rulers. Heinlein enjoyed challenging his readers' possible racial stereotypes by introducing strong, sympathetic characters, only to reveal much later that they were of African descent, e.g., in The Cat Who Walks Through Walls, Tunnel in the Sky,[14] and Friday. The Moon is a Harsh Mistress and Podkayne of Mars both contain incidents of racial prejudice or injustice against their protagonists.[15] In the context of science fiction before the 1960s, the mere existence of dark-skinned characters is a remarkable novelty; in the science fiction genre of that era, green occurred more often than brown. Heinlein repeatedly denounces racism in his non-fiction works, including numerous examples in Expanded Universe.

Asian civilization is sometimes treated negatively in Heinlein's work, as in his 1949 novel Sixth Column, in which the U.S. defends itself against invasion using a ray that only kills people with "Asiatic blood"; the idea for the story was pushed on Heinlein by editor John W. Campbell, and Heinlein wrote later that he was embarrassed by it.[16] Tunnel in the Sky and Farmer in the Sky both contain negative depictions of overpopulation in Asia. Some readers may mistake Heinlein's dislike of communist China for a dislike of Asians.[17] Heinlein did include sympathetic Asian characters in several of his stories.[18]

It is interesting, although perhaps risky, to interpret some of the alien species in Heinlein's fiction in terms of an allegorical representation of human ethnic groups. Double Star, Red Planet, and Stranger in a Strange Land all deal with tolerance and understanding between humans and Martians. Several of his stories, such as "Jerry Was a Man," The Star Beast, and Red Planet, involve the idea of nonhumans who are incorrectly judged as being less than human. Although it has been suggested that the strongly hierarchical and anti-individualistic "bugs" in Starship Troopers were meant to represent the Chinese or Japanese, Heinlein wrote the book in response to the unilateral ending of nuclear testing by the U.S., so it is more likely that they were intended to represent communism. The slugs in The Puppet Masters are likewise clearly and explicitly identified as metaphors for communism. A problem with interpreting aliens as stand-ins for races of Homo sapiens is that Heinlein's aliens generally occupy an entirely different mental world than humans. For example, Methuselah's Children depicts two alien races: the Jockaira are sentient domesticated animals ruled by a second, godlike species. In his early juvenile fiction, the Martians and Venerians are depicted as ancient, wise races who seldom deign to interfere in human affairs.

Individualism and self-determination

Many of Heinlein's novels are stories of revolts against political oppression, for example:

- Residents of a Lunar penal colony, aided by a self-aware computer, rebel against the Warden and Lunar Authority (and eventually Earth) in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress

- Colonists rebel against Earth in Between Planets and Red Planet.

- Secularists overthrow a religious dictatorship in "If This Goes On—".

But in keeping with his belief in individualism, his more sophisticated work for adults often portrays both the oppressors and the oppressed with considerable ambiguity. In Farnham's Freehold, the protagonist's son accepts the security that comes with being castrated. In The Star Beast and Glory Road, absolute monarchs are depicted positively. In The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, prerevolutionary life under the Lunar Authority is portrayed as a kind of anarchist or libertarian utopia; projections of economic disaster are the true (and secret) justification for the revolution, which brings with it the evils of republican government. Novels such as Stranger in a Strange Land and Friday revolve around individual rebellions against oppression by society rather than by government. The common thread, then, is the struggle for self-determination of individuals, rather than of nations. The ability of the individual to create himself is explored deeply in stories such as I Will Fear No Evil, "—All You Zombies—", and "By His Bootstraps". We are invited to wonder, what would humanity be if we shaped customs to our benefit, and not the other way around? In Heinlein's view, as outlined in For Us, the Living, humanity would not only be happier, but perceptually, behaviorally, and morally aligned with reality.

Sexual liberation

For Heinlein, personal liberation included sexual liberation, and free love was a major subject of his writing starting from the 1939 For Us, The Living. Beyond This Horizon (1942) cleverly subverts traditional gender roles in a scene in which the protagonist demonstrates his archaic gunpowder gun for his friend and discusses how useful it would be in dueling --- after which the discussion turns to the shade of his nail polish. "—All You Zombies—" (1959) is the story of a person who undergoes a sex change operation, goes back in time, has sex with herself, and gives birth to herself.

Sexual freedom and the elimination of sexual jealousy are a major theme of Stranger in a Strange Land (1961), in which the straitlaced nurse Jill acts as a dramatic foil for the less parochial characters Jubal and Mike. Over the course of the story, Jill learns to embrace her innate tendency toward exhibitionism, and to be more accepting of other people's sexuality (e.g., Duke's fondness for sadomasochistic pornography). As discussed in more detail in the book's article, two brief negative references to homosexuality have been interpreted by some readers as being homophobic, but both deal with Jill's hang-ups, and one is a discussion of Jill's thoughts. Homosexuality is treated with approval -- even gusto -- in books such as the 1970 I Will Fear No Evil, which posits the social recognition of six innate genders, consisting of all the combinations of male and female with straight, gay, and bisexual.

In later books, Heinlein dealt with incest and the sexual nature of children, topics that, Freud notwithstanding, touch a raw nerve with many readers. In Time Enough For Love, Lazarus Long uses genetic arguments to dissuade a brother and sister he's adopted from sexual experimentation with each other. A common shtick in many of the books is that a young girl climbs into her father's lap or bed, but he kicks her out. The protagonist of The Cat Who Walks Through Walls recalls a homosexual experience with a boy scout leader, which he didn't find unpleasant, and the same novel deals with Long's strong sexual attraction to his own mother, whom he goes back in time to rescue. In Heinlein's treatment of the possibility of sex between adults and children, some readers may feel that he dodges many of the valid reasons for the taboo by portraying the sexual attractions or actual sex as taking place only between Nietzschean supermen, who are so enlightened that they can avoid all the ethical and emotional pitfalls.

Philosophy

In his book To Sail Beyond the Sunset, Heinlein has the main character, Maureen, state that the purpose of metaphysics is to ask questions: Why are we here? Where are we going after we die? (and so on), and that you are not allowed to answer the questions. Asking the questions is the point for metaphysics, but answering them is not, because once you answer them, you cross the line into religion. Maureen does not state a reason for this; she simply remarks that such questions are "beautiful" but lack answers. The implication seems to be as follows: because (as Heinlein held) deductive reasoning is strictly tautological and because inductive reasoning is always subject to doubt, the only source of reliable "answers" to such questions is direct experience—which we do not have. Maureen's son/lover Lazarus Long makes a related remark in Time Enough For Love. In order for us to answer the "big questions" about the universe, Lazarus states at one point, it would be necessary to stand outside the universe.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Heinlein was deeply interested in Alfred Korzybski's General Semantics and attended a number of seminars on the subject. His views on epistemology seem to have flowed from that interest, and his fictional characters continue to express Korzybskian views to the very end of his writing career. Many of his stories, such as Gulf, "If This Goes On—", and Stranger in a Strange Land, depend strongly on the premise, extrapolated from the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, that by using a correctly designed language, one can liberate oneself mentally, or even become a superman. He was also strongly affected by the religious philosopher P.D. Ouspensky.[19] Freudianism and psychoanalysis were at the height of their influence during the peak of Heinlein's career, and stories such as Time for the Stars indulged in psychoanalysis. However, he was skeptical about Freudianism, especially after a struggle with an editor who insisted on reading Freudian sexual symbolism into his juvenile novels. He was strongly committed to cultural relativism, and the sociologist Margaret Mader in his novel Citizen of the Galaxy is clearly a reference to Margaret Mead; in the World War II era, cultural relativism was the only intellectual framework that offered a clearly reasoned alternative to racism, which Heinlein was ahead of his time in opposing. Many of these sociological and psychological theories have been criticized, debunked, or heavily modified in the last fifty years, and Heinlein's use of them may now appear credulous and dated to many readers. The critic Patterson says "Korzybski is now widely regarded as a crank,"[20] although others disagree.

Influence

Heinlein is usually identified, along with Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke, as one of the three masters of science fiction to arise in the so-called Golden Age of science fiction, associated with John W. Campbell and his magazine Astounding Science Fiction. However, in the 1950s he was a leader in bringing science fiction out of the low-paying and less prestigious pulp ghetto.

He was at the top of his form during, and himself helped to initiate, the trend toward social science fiction, which went along with a general maturing of the genre away from space opera to a more literary approach touching on such adult issues as politics and sexuality. In reaction to this trend, hard science fiction began to be distinguished as a separate subgenre, but paradoxically Heinlein is also considered a seminal figure in hard science fiction, due to his extensive knowledge of engineering, and the careful scientific research demonstrated in his stories.

Outside the science fiction community, several words coined by Heinlein have passed into common English usage: waldo, TANSTAAFL, and grok. He was influential in making space exploration seem to the public more like a practical possibility. His stories in publications such as the Saturday Evening Post took a matter-of-fact approach to their outer-space setting, rather than the "gee whiz" tone that had previously been common. The documentary-like film Destination Moon advocated a space race with the Soviets almost a decade before such an idea became commonplace, and was promoted by an unprecedented publicity campaign in print publications. Many of the astronauts and others working in the U.S. space program grew up on a diet of the Heinlein juveniles, as shown by the naming of a crater on Mars after him, and a tribute interspersed by the Apollo 15 astronauts into their radio conversations while on the moon.[21] Heinlein also was guest commentator for Walter Cronkite during Neil Armstrong's Apollo 11 moon landing.

Bibliography

Heinlein's fictional works can be found in the library under Library of Congress PS3515.E288, or under Dewey 813.54.

Known pseudonyms include Anson MacDonald, Lyle Monroe, John Riverside, Caleb Saunders, and Simon York.[22]

Novels

Novels marked with an * are generally considered juvenile novels, although some works defy easy categorization.

Early Heinlein novels

- For Us, The Living: A Comedy of Customs (1939)

- Methuselah's Children (1941)

- Beyond This Horizon (1942)

- Rocket Ship Galileo (1947) *

- Space Cadet (1948) *

- Red Planet (1949) *

- Sixth Column aka The Day After Tomorrow (1949)

- Farmer in the Sky (1950) (Retro Hugo Award, 1951) *

- Between Planets (1951) *

- The Rolling Stones aka Space Family Stone (1952) *

- The Puppet Masters (1951)

- Double Star (1956) (Hugo Award, 1956)

- Starman Jones (1953) *

- The Star Beast (1954) *

- Tunnel in the Sky (1955) *

- Time for the Stars (1956) *

- Citizen of the Galaxy (1957) *

- The Door into Summer (1957)

- Have Space Suit—Will Travel (1958) *

- Starship Troopers (1959) (Hugo Award, 1960) *

Mature Heinlein novels

- Stranger in a Strange Land (1961) (Hugo Award, 1962)

- Podkayne of Mars (1963) *

- Glory Road (1963)

- Farnham's Freehold (1965)

- The Moon is a Harsh Mistress (1966) (Hugo Award, 1967)

- I Will Fear No Evil (1970)

- Time Enough For Love (1973)

Late Heinlein novels

- The Number of the Beast (1980)

- Friday (1982)

- Job: A Comedy of Justice (1984)

- The Cat Who Walks Through Walls (1985)

- To Sail Beyond the Sunset (1987)

Short fiction

"Future History" short fiction

- Life-Line (1939)

- Misfit (1939)

- The Roads Must Roll (1940)

- Requiem (1940)

- "If This Goes On—" (1940)

- Coventry (1940)

- Blowups Happen (1940)

- Solution Unsatisfactory (1940)

- Universe (1941)

- "—We Also Walk Dogs" (1941)

- Common Sense (1941)

- Methuselah's Children (1941)

- Logic of Empire (1941)

- Space Jockey (1947)

- "It's Great to Be Back!" (1947)

- The Green Hills of Earth (1947)

- Ordeal in Space (1948)

- The Long Watch (1948)

- Gentlemen, Be Seated! (1948)

- The Black Pits of Luna (1948)

- Delilah and the Space Rigger (1949)

- The Man Who Sold the Moon (Retro Hugo Award, 1951)

Other short fiction

- Waldo (1940)

- They (1941)

- "—And He Built a Crooked House—" (1941)

- By His Bootstraps (1941)

- Lost Legacy (1941)

- Elsewhen (1941)

- The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag (1942)

- Magic, Inc. (1942)

- Jerry Was a Man (1947)

- Our Fair City (1948)

- Gulf (1949)

- The Year of the Jackpot (1952) -- themes: statistical cycles; social and physical apocalypse

- Project Nightmare (1953)

- Sky Lift (1953)

- The Menace From Earth (1957)

- The Man Who Traveled in Elephants (1957)

- "—All You Zombies—" (1959)

- Searchlight (1962)

- Free Men (1966)

Collections

- The Man Who Sold the Moon (1950)

- Waldo & Magic, Inc. (1950)

- The Green Hills of Earth (1951)

- Orphans of the Sky (1951) - Universe and Commonsense

- Assignment in Eternity (1953)

- Revolt in 2100 (1953)

- The Robert Heinlein Omnibus (1958)

- The Menace from Earth (1959)

- The Unpleasant Profession of Jonathan Hoag (1959)

- Three by Heinlein (1965)

- A Robert Heinlein Omnibus (1966)

- The Worlds of Robert A. Heinlein (1966)

- The Past Through Tomorrow (1967)

- The Best of Robert A. Heinlein (1973)

- Expanded Universe (1980)

- A Heinlein Trio (Doubleday,1980) - The Puppet Masters, Double Star, and The Door Into Summer

- The Fantasies of Robert A. Heinlein (1999)

- Infinite Possibilities (2003) - Tunnel in the Sky, Time for the Stars, and Citizen of the Galaxy

- To the Stars (2004) - Between Planets, The Rolling Stones, Starman Jones, and The Star Beast

- Four Frontiers (2005) - Rocket Ship Gallileo, Space Cadet, Red Planet, and Farmer in the Sky

Nonfiction

- Grumbles from the Grave (1989)

- Take Back Your Government: A Practical Handbook for the Private Citizen (1992)

- Tramp Royale (1992)

Spinoffs

- The Notebooks of Lazarus Long illuminated by D.F Vassallo (1978)

- Fate's Trick by Matt Costello (1988)

- Requiem: New Collected Works by Robert A. Heinlein and Tributes to the Grand Master (1992)

Filmography

- Destination Moon (book Rocket Ship Galileo) (screenplay) (technical advisor) (1950) IMDb (Retro Hugo Award, 1951)

- Tom Corbett, Space Cadet (1950) (book Space Cadet) IMDb

- Project Moon Base (1953) IMDb

- The Brain Eaters (book The Puppet Masters) (uncredited) (1959) IMDb

- Uchu no Senshi (Japanese) (TV Series) (1988) ANN

- Red Planet TV mini-series (book) (1994) IMDb

- Robert A. Heinlein's The Puppet Masters (book) (1994) IMDb

- Starship Troopers (book) ([1997]) IMDb

- Roughnecks: The Starship Troopers Chronicles TV series (1999) IMDb

See also: List of Robert Heinlein characters

External links

- The Heinlein Society and their FAQ.

- Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award

- Robert & Virginia Heinlein Prize

- Robert A. Heinlein, Grandmaster of Science Fiction

- Centennial Celebration in Kansas City, July 7, 2007

- Internet Book Database of Fiction bibliography

- Good bibliography, essays, news, links, etc.

- 1952 Popular Mechanics tour of Heinlein's Colorado house. accessed June 3, 2005

- Photos of Heinlein's 1963 Colorado bomb shelter dramatized in Farnham's Freehold accessed June 3, 2005

- Robert A. Heinlein at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Illustrated list of Heinlein fiction

Notes

- ^ http://members.aol.com/agplusone/robert_a._heinlein_a_biogr.htm

- ^ Heinlein's biography, as given on the Heinlein Society web site, endorsed by his estate, says about his first wife, "We do know her name and other information on her life (we helped track down her and her fate) but are withholding it until Bill Patterson presents the material in his upcoming biography on Heinlein (so don't ask, we won't tell)." See also the biography at the end of For Us, the Living, 2004 edition, p. 261.

- ^ Isaac Asimov, I, Asimov

- ^ Afterword to For Us, the Living, 2004 edition, p. 245.

- ^ Heinlein was running as a left-wing Democrat in a conservative district, and never made it past the Democratic primary because of trickery by his Republican opponent (afterword to For Us, the Living, 2004 edition, p. 247). Also, an unfortunate juxtaposition of events had Konrad Henlein making headlines in the Sudetenlands.

- ^ Tramp Royale, 1992, uncorrected proof, ISBN 0-441-82184-7, p. 62

- ^ On Paul Dirac and antimatter, and on blood chemistry. A version of the former, titled "Paul Dirac, Antimatter, and You," was published in the anthology Expanded Universe, and demonstrates both Heinlein's skill as a popularizer and his lack of depth in physics; an afterword gives a normalization equation and presents it, incorrectly as being the Dirac equation.

- ^ An experimental novelization of an outline and notes created by Heinlein in 1958 is now being written by Spider Robinson. His posthumously published nonfiction includes a selection of letters edited by his wife, Virginia, his book on practical politics written in 1946, a travelogue of their first around-the-world tour in 1954. Podkayne of Mars and Red Planet, which were edited against his wishes in their original release, have been reissued in restored editions. Stranger In a Strange Land was originally published in a shorter form, but both the long and short versions are now simultaneously available in print.

- ^ Robert A. Heinlein, Expanded Universe, foreword to Free Men, p. 207 of Ace paperback edition.

- ^ Many of these were first published in serial form under other titles, e.g., Farmer in the Sky was published as "Satellite Scout" in the Boy Scout magazine Boy's Life.

- ^ The importance Heinlein attached to privacy was made clear in his fiction (e.g., For Us, the Living), but also in several well known examples from his life. He had a falling out with Alexei Panshin, who wrote an important book analyzing Heinlein's fiction; Heinlein stopped cooperating with Panshin because he accused Panshin of "[attempting to] pry into his affairs and to violate his privacy." Heinlein wrote to Panshin's publisher threatening to sue, and stating, "You are warned that only the barest facts of my private life are public knowledge...." [23]. In his 1961 speech at WorldCon, where he was guest of honor, he advocated building bomb shelters and caching away unregistered weapons,[24] and his own house in Colorado Springs included a bomb shelter.[25] Heinlein was a nudist, and built a fence around his house in Santa Cruz to keep out the counterculture types who had learned of his ideas through Stranger in a Strange Land [26]. In his later life, Heinlein studiously avoided revealing the story of his early involvement in left-wing politics,[27], and made strenuous efforts to block publication of information he had revealed to prospective biographer Sam Moskowitz.[28]

- ^ The story that Stranger in a Strange Land was used as inspiration by Charles Manson appears to be an urban folk tale; although some of Manson's followers had read the book, Manson himself later said that he had not. It is true that other individuals formed a quasi-religious organization called the Church Of All Worlds, after the religion founded by the primary characters in Stranger, but Heinlein had nothing to do with this, either, so far as is known. (see http://www.heinleinsociety.org/rah/faqworks.html)

- ^ Patterson and Thornton, 2001.

- ^ The reference in Tunnel in the Sky is subtle and ambiguous, but at least one college instructor who teaches the book reports that some students always ask, "Is he black?" (see [29]). The Cat Who Walks Through Walls was published with a dust jacket painting showing the protagonist as pale-skinned, although the book clearly states that he is dark-skinned; this was also true of the paperback release of Friday.

- ^ The Moon is a Harsh Mistress includes an incident in which the protagonist visits the Southern U.S., and is briefly jailed for polygamy, later learning that the "...range of color in Davis family was what got judge angry enough..." to have him arrested. Podkayne of Mars deals briefly with racial prejudice against the protagonist due to her mixed-race ancestry.

- ^ Heinlein later wrote that he had "had to reslant it to remove racist aspects of the original story line" and that he did not "consider it to be an artistic success." Robert A. Heinlein, Expanded Universe, foreword to Solution Unsatisfactory, p. 93 of Ace paperback edition.

- ^ Sixth Column concentrates more on the Japanese, and was first serialized in 1941, the year of the Pearl Harbor attack, although it was not published in book form until 1949, the year of the revolution in China. Tunnel in the Sky and Farmer in the Sky were both written after the revolution.

- ^ The protagonist in Starship Troopers is Filipino, and "Tiger" Kondo in The Cat Who Walks Through Walls is a cameo appearance by Yoji Kondo, a NASA scientist of Heinlein's acquaintance who also edited the tribute volume Requiem. A Japanese-American character plays a pivotal role in Sixth Column. The protagonist in Between Planets is assisted by a Chinese restaurant owner, a major character in the book.

- ^ http://members.aol.com/agplusone/robert_a._heinlein_a_biogr.htm

- ^ Patterson and Thornton, 2001, p. 120

- ^ http://www.hq.nasa.gov/alsj/a15/a15.clsout3.html#1675120

- ^ http://www.nitrosyncretic.com/rah/rahfaq.html

References

Critical

- H. Bruce Franklin. 1980. Robert A. Heinlein: America as Science Fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 195027469.

- A critique of Heinlein from a Marxist perspective. Somewhat out of date, since Franklin was not aware of Heinlein's work with EPIC Movement. Includes a biographical chapter, which incorporates some original research on Heinlein's family background, but contains many of the same omissions and inaccuracies as other 20th-century bios of Heinlein.

- James Gifford. 2000 Robert A. Heinlein: A Reader's Companion. Sacramento: Nitrosyncretic Press. ISBN 0967987415 (hardcover), 0967987407 (trade paperback).

- A comprehensive bibliography, with roughly one page of commentary on each of Heinlein's works.

- Alexei Panshin. 1968. Heinlein in Dimension. Advent. ISBN 0911682120. Online edition at [30]

- William H. Patterson, Jr. and Andrew Thornton. 2001. The Martian Named Smith: Critical Perspectives on Robert A. Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land. Sacramento: Nitrosyncretic Press. ISBN 0967987423.

- Tom Shippey. 2000. "Starship Troopers, Galactic Heroes, Mercenary Princes: the Military and its Discontents in Science Fiction", in Alan Sandison and Robert Dingley, ed.s, Histories of the Future: Studies in Fact, Fantasy and Science Fiction. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 0312236042.

Biographical

- Robert A. Heinlein. 2004. For Us, the Living. New York: Scribner. ISBN 074325998X.

- Includes an introduction by Spider Robinson, an afterword by Robert H. James with a long biography, and a shorter biographical sketch.

- Template:Journal reference issue Also available at Robert A. Heinlein, a Biographical Sketch. Retrieved June 1, 2005.

- A lengthy essay that treats Heinlein's own autobiographical statements with skepticism.

- The Heinlein Society and their FAQ. Retrieved May 30, 2005.

- Contains a shorter version of the Pattersion bio.

- Robert A. Heinlein. 1989. Grumbles From the Grave. New York: Del Rey.

- Incorporates a substantial biographical sketch by Virginia Heinlein, which hews closely to his earlier official bios, omitting the same facts (the first of his three marriages, his early left-wing political activities) and repeating the same fictional anecdotes (the short story contest).

- Elizabeth Zoe Vicary. 2000. American National Biography Online article, Heinlein, Robert Anson. Retrieved June 1, 2005 (not available for free).

- Repeats many incorrect statements from Heinlein's fictionalized professional bio.

- Robert A. Heinlein. 1980. Expanded Universe. New York: Ace. ISBN 0441218881 .

- Autobiographical notes are interspersed in the anthology.

- Reprinted by Baen, hardcover October 2003, ISBN 0743471598

- Reprinted by Baen, paperback July 2005, ISBN 0743499158

- Electronic edition available at: webscription.net (not free)

- Autobiographical notes are interspersed in the anthology.