European Union

- See also the List of European Union pages

The European Union or EU is an international organisation of European states, established by the Treaty on European Union (the Maastricht treaty). The European Union is the most powerful regional organization in existence, in some ways resembling a state, though not fully, as members states maintain diplomatic representations in other states. Some legal scholars believe that it should not be considered as an international organisation at all, but rather as a sui generis entity.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Current issues

Major issues concerning the European Union at the moment include its enlargement south and east (see below), the European constitution proposed by the Convention, the Union's relationship with the United States of America and participation in the Euro by those member states currently outside the Eurozone.

Origins

The original impetus for the founding of (what was later to become) the European Union was the desire to rebuild Europe after the disastrous events of World War II, and to prevent Europe from ever again falling victim to the scourge of war.

Methods

To accomplish this aim, the European Union attempts to form infrastructure that crosses state borders. The harmonized standards create a larger, more efficient market, because the member states can form a single customs union without loss of health or safety. For example, states whose people would never agree to eat the same food might still agree on standards for labelling and cleanliness.

The power of the European Union reaches far beyond its borders because to sell within it, it is helpful to conform to its standards. Once a non-member country's factories, farmers and merchants conform to EU standards, most of the costs of joining the union have been sunk. At that point, harmonizing laws to become a full member creates more wealth (by eliminating the customs costs) with only the tiny investment of actually changing the laws. This has led some commentators to compare the EU to a computer virus.

History

The body was originally known as the European Economic Community (informally called the Common Market in the UK), this later changed to the European Community and then to the European Union. The EU has evolved from a trade body into an economic and political partnership.

For a more detailed history, see the article History of the European Union.

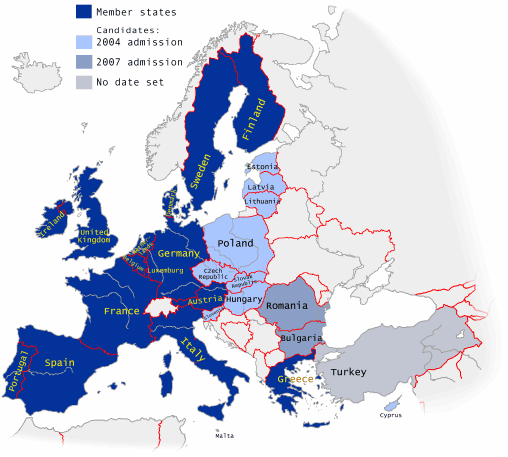

Member states and enlargement

- main articles: European Union member states, Enlargement of the European Union

At present, the European Union comprises 15 member states. In 1950 the six founding members were:

Nine further states have joined in successive waves of enlargement:

- in 1973: Ireland, the United Kingdom and Denmark

- in 1981: Greece

- in 1986: Spain and Portugal

- in 1995: Finland, Sweden and Austria

Note: In 1990 the European Union territory was effectively enlarged when East and West Germany were united.

Further waves of enlargement are planned:

- in 2004 (on 1 May): Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia

- in 2007 (provisional date, no firm agreement): Bulgaria and Romania.

Negotiations with Turkey are likely to start in the next couple of years.

The total area of the 15 member state European Union is 3,235,000 km². Were it a country, it would be the eighth largest in the world by area. The number of EU citizens (all EU member State citizens, under the terms of the Maastricht treaty) is approximately 379 million as of October 2001. This is the third largest in the world after India and China.

Economic status

Currently (February 2004) the EU, considered as a unit, has the largest economy in the world, with a 2002 GDP of 8,447 billion euro. The US economy, classified as the second, has a GDP of 10,450 billion dollars, that calculated by the current rate 1.28$ for euro gives 8,170 bilion euro.

The EU economy is expected to grow further over the next decade as more countries join the union - especially that the new States are usually poorer than the EU average, and hence expected fast GDP growth will help achieve the dynamic of the united europe. However, GDP per capita the whole Union will fall over the short-term.

Main policies

As the changing name of the European Union (from European Economic Community to European Community to European Union) suggests, it has evolved over time from a primarily economic union to an increasingly political one. This trend is highlighted by the increasing number of policy areas that fall within EU competence: political power has tended to shift upwards from the Member States to the EU.

This picture of increasing centralisation is counter-balanced by two points.

First, some Member States have a domestic tradition of strong regional government. This has led to an increased focus on regional policy and the European regions. A Committee of the Regions was established as part of the Treaty of Maastricht.

Second, EU policy areas cover a number of different forms of co-operation.

- Autonomous decision making: Member States have granted the European Commission power to issue decisions in certain areas such as competition law, State Aid control and liberalisation.

- Harmonisation: Member State laws are harmonised through the EU legislative process, which involves the European Commission, European Parliament and Council of Ministers. As a result of this European Union Law is increasingly present in the systems of the Member States.

- Co-operation: Member States, meeting as the Council of Ministers agree to co-operate and co-ordinate their domestic policies.

The tension between EU and national (or sub-national) competence is an enduring one in the development of the European Union. (See also Intergovernmentalism v Supranationalism (below), Euroscepticism.)

All prospective members must enact legislation in order to bring them into line with the common European legal framework, known as the Acquis Communautaire. (See also EFTA, EEA and Single European Sky).

Single Market: Internal aspects

- Free trade of goods and services among member states (an aim further extended to three of the four EFTA states by the European Economic Area, EEA)

- A common EU competition law controlling anti-competitive activities of companies (through antitrust law and merger control) and Member States (through the State Aids regime).

- Removal of border controls between its member states (excluding the UK and Ireland, which have derogations).

- Freedom for citizens of its member states to live and work anywhere within the EU, provided they can support themselves (also extended to the other EEA states).

- Free movement of capital between member states (and other EEA states).

- Harmonisation of government regulations, corporations law and trademark registrations.

- A single currency, the Euro (excluding the UK, Sweden and Denmark, which have derogations).

- A large amount of environmental policy co-ordination throughout the Union.

- A Common Agricultural Policy and a Common Fisheries Policy.

- Common system of indirect taxation, the VAT, as well as common customs duties and excises on various products.

- Funding for the development of disadvantaged regions (structural and cohesion funds).

- Funding for research.

Single market: External aspects

- A common external customs tariff, and a common position in international trade negotiations.

- Funding for programmes in candidate countries and other Eastern European countries, as well as aid to many developing countries.

Increasing co-operation and/or harmonisation of non-commercial areas

- Freedom for its citizens to vote in local government and European Parliament elections in any member state.

- Co-operation in criminal matters, including sharing of intelligence (through EUROPOL and the Schengen Information System), agreement on common definition of criminal offences and expedited extradition procedures.

- A common foreign policy as a future objective, however this has some way to go before being realised. The divisions between the member states regarding the Iraq crisis in 2003 highlights just how far off this objective could be before it becomes a reality.

- A common security policy as an objective, including the creation of a 60,000-member Rapid Reaction Force for peacekeeping purposes, an EU military staff and an EU satellite centre (for intelligence purposes).

- Common policy on asylum and immigration.

Structure of the European Union

The role of the European Community within the Union

In practice, the European Community is simply the old name for the European Union. Legally, however, they must be distinguished. The European Union has no legal personality; it is not an international organisation, but a mere bloc of states. The European Community is one of two international organisations these states are members of -- the other is the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom). There was once a third organisation, the European Coal and Steel Community, but it ceased to exist in 2002. These three organisations used to have separate institutions; but in 1961 their institutions were merged, though legally speaking they are still separate organisations (ie: the single Commission acts for EC and Euratom, which are legally separate organisations).

Intergovernmentalism vs. supranationalism

A basic tension exists within the European Union between intergovernmentalism and supranationalism. Intergovernmentalism is a method of decision-making in international organisations where power is possessed by the member-states and decisions are made by unanimity. Independent appointees of the governments or elected representatives have solely advisory or implementational functions. Intergovernmentalism is used by most international organisations today.

An alternative method of decision-making in international organisations is supranationalism. In supranationalism power is held by independent appointed officials or by representatives elected by the legislatures or people of the member states. Member-state governments still have power, but they must share this power with other actors. Furthermore, decisions are made by majority votes, hence it is possible for a member-state to be forced by the other member-states to implement a decision against its will.

Some forces in European Union politics favour the intergovernmental approach, while others favour the supranational path. Supporters of supranationalism argue that it allows integration to proceed at a faster pace than would otherwise be possible. Where decisions must be made by governments acting unanimously, decisions can take years to make, if they are ever made. Supporters of intergovernmentalism argue that supranationalism is a threat to national sovereignty, and to democracy, claiming that only national governments can possess the necessary democratic legitimacy. Intergovernmentalism has historically been favoured by France, and by more Eurosceptic nations such as Britain and Denmark; while more integrationist nations such as Belgium, Germany, and Italy have tended to prefer the supranational approach.

In practice the European Union strikes a balance between two approaches. This balance however is complex, resulting in the often labyrinthine complexity of its decision-making procedures.

Starting in March 2002, a Convention on the Future of Europe again looked at this balance, among other things, and proposed changes. These changes were discussed at an Intergovernmental Conference (IGC) in December 2003, but no agreement was reached.

The Three Pillars

European Union policies are divided into three main areas, called pillars. The first or 'Community' pillar concerns economic, social and environmental policies. The second or 'Common Foreign and Security Policy' (CFSP) pillar concerns foreign policy and military matters. The third or 'Justice and Home Affairs' (JHA) pillar concerns co-operation in the fight against crime.

Within each pillar, a different balance is struck between the supranational and intergovernmental principles. Supranationalism is strongest in the first pillar, while the other two pillars function along more intergovernmental lines.

In the CFSP and JHA pillars the powers of the Parliament, Commission and European Court of Justice with respect to the Council are significantly limited, without however being altogether eliminated.

The balance struck in the first pillar is frequently referred to as the "community method", since it is that used by the European Community.

Origin of the three pillars structure

The pillar structure had its historical origins in the negotiations leading up to the Maastricht treaty. It was desired to add powers to the Community in the areas of foreign policy, security and defence policy, asylum and immigration policy, criminal co-operation, and judicial co-operation.

However, some member-states opposed the addition of these powers to the Community on the grounds that they were too sensitive to national sovereignty for the community method to be used, and that these matters were better handled intergovernmentally. To the extent that at that time the Community dealt with these matters at all, they were being handled intergovernmentally, principally in European Political Co-operation (EPC).

As a result, these additional matters were not included in the European Community; but were tacked on externally to the European Community in the form of two additional 'pillars'. The first additional pillar (Common Foreign and Security Policy, CFSP) deal with foreign policy, security and defence issues, while the second additional pillar (JHA, Justice and Home Affairs), dealt with the remainder.

Recent amendments in the treaties of Amsterdam and Nice have made the additional pillars increasingly supranational. Most important among these has been the transfer of policy on asylum, migration and judicial co-operation in civil matters to the Community pillar, effected by the Amsterdam treaty. Thus the third pillar has been renamed Police and Judicial Co-operation in Criminal Matters, or PJCC.

The Single Institutional Framework

The three communities, and the three pillars possess a common institutional structure. The European Union has five institutions:

- European Parliament

- European Commission

- European Court of Justice (incorporating the Court of First Instance)

- Council of the European Union

- European Court of Auditors

There are also two advisory committees to the above institutions, which advise them on economic and social (principally relations between workers and employers) and regional issues:

There are also several other bodies to implement particular policies, established either under the treaties or by secondary legislation:

- European Central Bank

- European System of Central Banks

- European Investment Bank

- European Investment Fund

- Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market

- European Environment Agency

Finally the European Ombudsman watches for abuses of power by EU institutions.

See also

- Enlargement of the European Union

- European flag

- European Union Law

- History of the European Union

- Holy Roman Empire

- List of Europeans

- Official Journal of the European Communities

- Trade bloc

- United States of Europe

- Value-added tax

External links

- The European Union On-Line - Official site (in 11 languages)

- EU Enlargement - Official site on EU enlargement

- EU in the USA - Official site of the EU delegation to the US

- EU Observer - Newssite focusing on the EU

- European Union Banknotes

- European Commission - Maps of Europe

- EU Treaties (Official EU website)