Structural engineering

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. |

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. |

Structural engineering is a field of engineering dealing with the analysis and design of structures that support or resist loads. Structural engineering is usually considered a speciality within civil engineering, but it can also be studied in its own right.[1]

Structural engineers are most commonly involved in the design of buildings and large nonbuilding structures[2] but they can also be involved in the design of machinery, medical equipment, vehicles or any item where structural integrity affects the item's function or safety. Structural engineers must ensure their designs satisfy given design criteria, predicated on safety (e.g. structures must not collapse without due warning) or serviceability and performance (e.g. building sway must not cause discomfort to the occupants).

Structural engineering theory is based upon physical laws and empirical knowledge of the structural performance of different geometries and materials. Structural engineering design utilises a relatively small number of basic structural elements to build up structural systems than can be very complex. Structural engineers are responsible for making creative and efficient use of funds, structural elements and materials to achieve these goals.[2]

The structural engineer

| Etymology |

|

The term structural derives from the Latin word structus, which is "to pile, build, assemble". The first use of the term structure was c.1440.[3] The term engineer derives from the old French term engin, meaning "skill, cleverness" and also 'war machine'. This term in turn derives from the Latin word ingenium, which means "inborn qualities, talent", and is constructed of in- "in" + gen-, the root of gignere, meaning "to beget, produce." The term engineer is related to ingenious.[4] The term structural engineer is generally applied to those who have completed a degree in civil engineering specializing in the design of structures, or a post-graduate degree in structural engineering. However, an individual can become a structural engineer through training and experience outside educational institutions as well, perhaps most notably under the Institution of Structural Engineers (UK) regulations. The training and experience requirements for structural engineers varies greatly, being governed in some way in most developed nations. In all cases the term is regulated to restrict usage to only those individuals having specialist knowledge of the requirements and design of safe, serviceable, and economical structures. The term engineer in isolation varies widely in its use and application, and can, depending on the geographical location of its use, refer to many different technical and creative professions in its common usage. |

Structural engineers are responsible for engineering design and analysis. Entry-level structural engineers may design the individual structural elements of a structure, for example the beams, columns, and floors of a building. More experienced engineers would be responsible for the structural design and integrity of an entire system, such as a building.

Structural engineers often specialise in particular fields, such as bridge engineering, building engineering, pipeline engineering, industrial structures or special structures such as vehicles or aircraft.

Structural engineering has existed since humans first started to construct their own structures. It became a more defined and formalised profession with the emergence of the architecture profession as distinct from the engineering profession during the industrial revolution in the late 19th Century. Until then, the architect and the structural engineer were often one and the same - the master builder. Only with the understanding of structural theories that emerged during the 19th and 20th century did the professional structural engineer come into existence.

The role of a structural engineer today involves a significant understanding of both static and dynamic loading, and the structures that are available to resist them. The complexity of modern structures often requires a great deal of creativity from the engineer in order to ensure the structures support and resist the loads they are subjected to. A structural engineer will typically have a four or five year undergraduate degree, followed by a minimum of three years of professional practice before being considered fully qualified.[5]

Structural engineers are licensed or accredited by different learned societies and regulatory bodies around the world (for example, the Institution of Structural Engineers in the UK)[5]. Depending on the degree course they have studied and/or the jurisdiction they are seeking licensure in, they may be accredited (or licensed) as just structural engineers, or as civil engineers, or as both civil and structural engineers.

History of structural engineering

Structural engineering dates back to at least 2700 BC when the step pyramid for Pharaoh Djoser was built by Imhotep, the first engineer in history known by name. Pyramids were the most common major structures built by ancient civilisations because the structural form of a pyramid is inherently stable and can be almost infinitely scaled (as opposed to most other structural forms, which cannot be linearly increased in size in proportion to increased loads).[6]

Throughout ancient and medieval history most architectural design and construction was carried out by artisans, such as stone masons and carpenters, rising to the role of master builder. No theory of structures existed and understanding of how structures stood up was extremely limited, and based almost entirely on empirical evidence of 'what had worked before'. Knowledge was retained by guilds and seldom supplanted by advances. Structures were repetitive, and increases in scale were incremental.[6]

No record exists of the first calculations of the strength of structural members or the behaviour of structural material, but the profession of structural engineer only really took shape with the industrial revolution and the re-invention of concrete (see History of concrete). The physical sciences underlying structural engineering began to be understood in the Renaissance and have been developing ever since.

Significant structural failures and collapses

Structural engineering has advanced significantly through the study of structural failures. The history of structural engineering contains many collapses and failures. Amongst the most significant[weasel words] failures and collapses are:

Dee Bridge

On 24 May, 1847 the Dee Bridge collapsed as a train passed over it, with the loss of 5 lives. It was designed by Robert Stephenson, using cast iron girders reinforced with wrought iron struts. The bridge collapse was subject to one of the first formal inquiries into a structural failure. The result of the enquiry was that the design of the structure was fundamentally flawed, as the wrought iron did not reinforce the cast iron at all, and due to repeated flexing it suffered a brittle failure due to fatigue.[7]

First Tay Rail Bridge

The Dee bridge disaster was followed by a number of cast iron bridge collapses, including the collapse of the first Tay Rail Bridge on 28 December 1879. Like the Dee bridge, the Tay collapsed when a train passed over it causing 75 people to lose their lives. The bridge failed because of poorly made cast iron, and the failure of the designer Thomas Bouch to consider wind loading on the bridge. The collapse resulted in cast iron largely being replaced by steel construction, and a complete redesign in 1890 of the Forth Railway Bridge. As a result, the Forth Bridge was the first entirely steel bridge in the world.[8]

First Tacoma Narrows Bridge

The 1940 collapse of Galloping Gertie, as the original Tacoma Narrows Bridge is known, is sometimes characterized in physics textbooks as a classical example of resonance; although, this description is misleading. The catastrophic vibrations that destroyed the bridge were not due to simple mechanical resonance, but to a more complicated oscillation between the bridge and winds passing through it, known as aeroelastic flutter. Robert H. Scanlan, father of the field of bridge aerodynamics, wrote an article about this misunderstanding[9]. This collapse, and the research that followed, led to an increased understanding of wind/structure interactions. Several bridges were altered following the collapse to prevent a similar event occurring again. The only fatality was 'Tubby' the dog.[8]

de Havilland Comet

In 1954, two de Havilland Comet C1 jet airliners, the world's first commercial airliner, crashed, killing all passengers. After lengthy investigations and the grounding of all Comet airliners, it was concluded that metal fatigue at the corners of the windows had resulted in the crashes. The square corners had led to stress concentrations which after continual stress cycles from pressurisation and de-pressurisation, failed catastropically in flight. The research into the failures led to significant improvements in understanding of fatigue loading of airframes, and the redesign of the Comet and all subsequent airliners to incorporate rounded corners to doors and windows.

Ronan Point

On 16 May, 1968 the 22 storey residential tower Ronan Point in the London borough of Newham collapsed when a relatively small gas explosion on the 18th floor caused a structural wall panel to be blown away from the building. The tower was constructed of precast concrete, and the failure of the single panel caused one entire corner of the building to collapse. The panel was able to be blown out because there was insufficient reinforcement steel passing between the panels. This also meant that the loads carried by the panel could not be redistributed to other adjacent panels, because there was no route for the forces to follow. As a result of the collapse, building regulations were overhauled to prevent "disproportionate collapse",[clarification needed] and the understanding of precast concrete detailing was greatly advanced. Many similar buildings were altered or demolished as a result of the collapse.[10]

Hyatt Regency walkway

On 17 July, 1981, two suspended walkways through the lobby of the Hyatt Regency in Kansas City, Missouri, collapsed, killing 114 people at a tea dance. The collapse was due to a late change in design, altering the method in which the rods supporting the walkways were connected to them, and inadvertently doubling the forces on the connection. The failure highlighted the need for good communication between design engineers and contractors, and rigorous checks on designs and especially on contractor proposed design changes. The failure is a standard case study on engineering courses around the world, and is used to teach the importance of ethics in engineering.[11][12]

Oklahoma City bombing

On 19 April, 1995, the nine storey concrete framed Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma was struck by a huge car bomb causing partial collapse, resulting in the deaths of 168 people. The bomb, though large, caused a significantly disproportionate collapse of the structure. The bomb blew all the glass off the front of the building and completely shattered a ground floor reinforced concrete column (see brisance). At second storey level a wider column spacing existed, and loads from upper storey columns were transferred into fewer columns below by girders at second floor level. The removal of one of the lower storey columns caused neighbouring columns to fail due to the extra load, eventually leading to the complete collapse of the central portion of the building. The bombing was one of the first to highlight the extreme forces that blast loading from terrorism can exert on buildings, and led to increased consideration of terrorism in structural design of buildings.[13]

9/11

In the September 11 attacks, two commercial airliners were deliberately crashed into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in New York City. The impact and resulting fires caused both towers to collapse within two hours. After the impacts had severed exterior columns and damaged core columns, the loads on these columns were redistributed. The hat trusses at the top of each building played a significant role in this redistribution of the loads in the structure.[14] The impacts dislodged some of the fireproofing from the steel, increasing its exposure to the heat of the fires. Temperatures became high enough to weaken the core columns to the point of creep and plastic deformation under the weight of higher floors. Perimeter columns and floors were also weakened by the heat of the fires, causing the floors to sag and exerting an inward force on exterior walls of the building.[15][16]

Specializations

Building structures

Structural building engineering includes all structural engineering related to the design of buildings. It is the branch of structural engineering that is close to architecture.

Structural building engineering is primarily driven by the creative manipulation of materials and forms and the underlying mathematical and scientific principles to achieve an end which fulfills its functional requirements and is structurally safe when subjected to all the loads it could reasonably be expected to experience, while being economical and practical to construct. This is subtly different to architectural design, which is driven by the creative manipulation of materials and forms, mass, space, volume, texture and light to achieve an end which is aesthetic, functional and often artistic.

The architect is usually the lead designer on buildings, with a structural engineer employed as a sub-consultant. The degree to which each discipline actually leads the design depends heavily on the type of structure. Many structures are structurally simple and led by architecture, such as multi-storey office buildings and housing, while other structures, such as tensile structures, shells and gridshells are heavily dependent on their form for their strength, and the engineer may have a more significant influence on the form, and hence much of the aesthetic, than the architect. Between these two extremes, structures such as stadia, museums and skyscrapers are complex both architecturally and structurally, and a successful design is a collaboration of equals.

The structural design for a building must ensure that the building is able to stand up safely, able to function without excessive deflections or movements which may cause fatigue of structural elements, cracking or failure of fixtures, fittings or partitions, or discomfort for occupants. It must account for movements and forces due to temperature, creep, cracking and imposed loads. It must also ensure that the design is practically buildable within acceptable manufacturing tolerances of the materials. It must allow the architecture to work, and the building services to fit within the building and function (air conditioning, ventilation, smoke extract, electrics, lighting etc). The structural design of a modern building can be extremely complex, and often requires a large team to complete.

Structural engineering specialties for buildings include:

- Earthquake engineering

- Façade engineering

- Fire engineering

- Roof engineering

- Tower engineering

- Wind engineering

Earthquake engineering structures

Earthquake engineering structures are those engineered to withstand various types of hazardous earthquake exposures at the sites of their particular location.

Earthquake engineering is treating its subject structures like defensive fortifications in military engineering but for the warfare on earthquakes. Both earthquake and military general design principles are similar: be ready to slow down or mitigate the advance of a possible attacker.

The main objectives of earthquake engineering are:

- Understand interaction of structures with the shaky ground.

- Foresee the consequences of possible earthquakes.

- Design, construct and maintain structures to perform at earthquake exposure up to the expectations and in compliance with building codes.

Earthquake engineering or earthquake-proof structure does not, necessarily, means extremely strong and expensive one like El Castillo pyramid at Chichen Itza shown above.

Now, the most powerful and budgetary tool of the earthquake engineering is base isolation which pertains to the passive structural vibration control technologies.

Civil engineering structures

Civil structural engineering includes all structural engineering related to the built environment. It includes:

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

The structural engineer is the lead designer on these structures, and often the sole designer. In the design of structures such as these, structural safety is of paramount importance (in the UK, designs for dams, nuclear power stations and bridges must be signed off by a chartered engineer).

Civil engineering structures are often subjected to very extreme forces, such as large variations in temperature, dynamic loads such as waves or traffic, or high pressures from water or compressed gases. They are also often constructed in corrosive environments, such as at sea, in industrial facilities or below ground.

Mechanical structures

The design of static structures assumes they always have the same geometry (in fact, so-called static structures can move significantly, and structural engineering design must take this into account where necessary), but the design of moveable or moving structures must account for fatigue, variation in the method in which load is resisted and significant deflections of structures.

The forces which parts of a machine are subjected to can vary significantly, and can do so at a great rate. The forces which a boat or aircraft are subjected to vary enormously and will do so thousands of times over the structure's lifetime. The structural design must ensure that such structures are able to endure such loading for their entire design life without failing.

These works can require mechanical structural engineering:

- Airframes and fuselages

- Boilers and pressure vessels

- Coachworks and carriages

- Cranes

- Elevators

- Escalators

- Marine vessels and hulls

Structural elements

Any structure is essentially made up of only a small number of different types of elements:

Many of these elements can be classified according to form (straight, plane / curve) and dimensionality (one-dimensional / two-dimensional):

| One-dimensional | Two-dimensional | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| straight | curve | plane | curve | |

| (predominantly) bending | beam | continuous arch | plate, concrete slab | lamina, dome |

| (predominant) tensile stress | rope | Catenary | shell | |

| (predominant) compression | pier, column | Load-bearing wall | ||

Columns

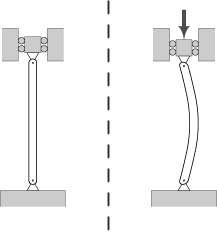

Columns are elements that carry only axial force - either tension or compression - or both axial force and bending (which is technically called a beam-column but practically, just a column). The design of a column must check the axial capacity of the element, and the buckling capacity.

The buckling capacity is the capacity of the element to withstand the propensity to buckle. Its capacity depends upon its geometry, material, and the effective length of the column, which depends upon the restraint conditions at the top and bottom of the column. The effective length is where is the real length of the column.

The capacity of a column to carry axial load depends on the degree of bending it is subjected to, and vice versa. This is represented on an interaction chart and is a complex non-linear relationship.

Beams

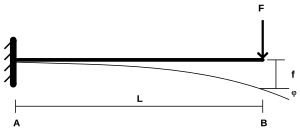

A beam may be:

- cantilevered (supported at one end only with a fixed connection)

- simply supported (supported vertically at each end; horizontally on only one to withstand friction, and able to rotate at the supports)

- continuous (supported by three or more supports)

- a combination of the above (ex. supported at one end and in the middle)

Beams are elements which carry pure bending only. Bending causes one section of a beam (divided along its length) to go into compression and the other section into tension. The compression section must be designed to resist buckling and crushing, while the tension section must be able to adequately resist the tension.

Struts and ties

1. Keystone 2. Voussoir 3. Extrados 4. Impost 5. Intrados 6. Rise 7. Clear span 8. Abutment

A truss is a structure comprising two types of structural element, ie struts and ties. A strut is a relatively lightweight column and a tie is a slender element designed to withstand tension forces. In a pin-jointed truss (where all joints are essentially hinges), the individual elements of a truss theoretically carry only axial load. From experiments it can be shown that even trusses with rigid joints will behave as though the joints are pinned. {{citation}}: Empty citation (help)

Trusses are usually utilised to span large distances, where it would be uneconomical and unattractive to use solid beams.

Plates

Plates carry bending in two directions. A concrete flat slab is an example of a plate. Plates are understood by using continuum mechanics, but due to the complexity involved they are most often designed using a codified empirical approach, or computer analysis.

They can also be designed with yield line theory, where an assumed collapse mechanism is analysed to give an upper bound on the collapse load (see Plasticity). This is rarely used in practice.

Shells

Shells derive their strength from their form, and carry forces in compression in two directions. A dome is an example of a shell. They can be designed by making a hanging-chain model, which will act as a catenary in pure tension, and inverting the form to achieve pure compression.

Arches

Arches carry forces in compression in one direction only, which is why it is appropriate to build arches out of masonry. They are designed by ensuring that the line of thrust of the force remains within the depth of the arch.

Catenaries

Catenaries derive their strength from their form, and carry transverse forces in pure tension by deflecting (just as a tightrope will sag when someone walks on it). They are almost always cable or fabric structures. A fabric structure acts as a catenary in two directions.

Structural engineering theory

Structural engineering depends upon a detailed knowledge of loads, physics and materials to understand and predict how structures support and resist self-weight and imposed loads. To apply the knowledge successfully a structural engineer will need a detailed knowledge of mathematics and of relevant empirical and theoretical design codes.

The criteria which govern the design of a structure are either serviceability (criteria which define whether the structure is able to adequately fulfill its function) or strength (criteria which define whether a structure is able to safely support and resist its design loads). A structural engineer designs a structure to have sufficient strength and stiffness to meet these criteria.

Loads imposed on structures are supported by means of forces transmitted through structural elements. These forces can manifest themselves as:

- tension (axial force)

- compression (axial force)

- shear

- bending, or flexure (a bending moment is a force multiplied by a distance, or lever arm, hence producing a turning effect or torque)

Loads

Some Structural loads on structures can be classified as live (imposed) loads, dead loads, earthquake (seismic) loads, wind loads, soil pressure loads, fluid pressure loads, impact loads, and vibratory loads. Live loads are transitory or temporary loads, and are relatively unpredictable in magnitude. They may include the weight of a building's occupants and furniture, and temporary loads the structure is subjected to during construction. Dead loads are permanent, and may include the weight of the structure itself and all major permanent components. Dead load may also include the weight of the structure itself supported in a way it wouldn't normally be supported, for example during construction.

Strength

Strength depends upon material properties. The strength of a material depends on its capacity to withstand axial stress, shear stress, bending, and torsion. The strength of a material is measured in force per unit area (newtons per square millimetre or N/mm², or the equivalent megapascals or MPa in the SI system and often pounds per square inch psi in the United States Customary Units system).

A structure fails the strength criterion when the stress (force divided by area of material) induced by the loading is greater than the capacity of the structural material to resist the load without breaking, or when the strain (percentage extension) is so great that the element no longer fulfills its function (yield).

See also:

Stiffness

Stiffness depends upon material properties and geometry. The stiffness of a structural element of a given material is the product of the material's Young's modulus and the element's second moment of area. Stiffness is measured in force per unit length (newtons per millimetre or N/mm), and is equivalent to the 'force constant' in Hooke's Law.

The deflection of a structure under loading is dependent on its stiffness. The dynamic response of a structure to dynamic loads (the natural frequency of a structure) is also dependent on its stiffness.

In a structure made up of multiple structural elements where the surface distributing the forces to the elements is rigid, the elements will carry loads in proportion to their relative stiffness - the stiffer an element, the more load it will attract. In a structure where the surface distributing the forces to the elements is flexible (like a wood framed structure), the elements will carry loads in proportion to their relative tributary areas.

A structure is considered to fail the chosen serviceability criteria if it is insufficiently stiff to have acceptably small deflection or dynamic response under loading.

The inverse of stiffness is the flexibility.

Safety factors

The safe design of structures requires a design approach which takes account of the statistical likelihood of the failure of the structure. Structural design codes are based upon the assumption that both the loads and the material strengths vary with a normal distribution.

The job of the structural engineer is to ensure that the chance of overlap between the distribution of loads on a structure and the distribution of material strength of a structure is acceptably small (it is impossible to reduce that chance to zero).

It is normal to apply a partial safety factor to the loads and to the material strengths, to design using 95th percentiles (two standard deviations from the mean). The safety factor applied to the load will typically ensure that in 95% of times the actual load will be smaller than the design load, while the factor applied to the strength ensures that 95% of times the actual strength will be higher than the design strength.

The safety factors for material strength vary depending on the material and the use it is being put to and on the design codes applicable in the country or region.

Load cases

A load case is a combination of different types of loads with safety factors applied to them. A structure is checked for strength and serviceability against all the load cases it is likely to experience during its lifetime.

Typical load cases for design for strength (ultimate load cases; ULS) are:

- 1.4 x Dead Load + 1.6 x Live Load

- 1.2 x Dead Load + 1.2 x Live Load + 1.2 x Wind Load

A typical load case for design for serviceability (characteristic load cases; SLS) is:

- 1.0 x Dead Load + 1.0 x Live Load

Different load cases would be used for different loading conditions. For example, in the case of design for fire a load case of 1.0 x Dead Load + 0.8 x Live Load may be used, as it is reasonable to assume everyone has left the building if there is a fire.

In multi-story buildings it is normal to reduce the total live load depending on the number of stories being supported, as the probability of maximum load being applied to all floors simultaneously is negligibly small.

It is not uncommon for large buildings to require hundreds of different load cases to be considered in the design.

Newton's laws of motion

The most important natural laws for structural engineering are Newton's Laws of Motion

Newton's first law states that every body perseveres in its state of being at rest or of moving uniformly straight forward, except insofar as it is compelled to change its state by force impressed.

Newton's second law states that the rate of change of momentum of a body is proportional to the resultant force acting on the body and is in the same direction. Mathematically, F=ma (force = mass x acceleration).

Newton's third law states that all forces occur in pairs, and these two forces are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction.

With these laws it is possible to understand the forces on a structure and how that structure will resist them. The Third Law requires that for a structure to be stable all the internal and external forces must be in equilibrium. This means that the sum of all internal and external forces on a free-body diagram must be zero:

- : the vectorial sum of the forces acting on the body equals zero. This translates to

- Σ H = 0: the sum of the horizontal components of the forces equals zero;

- Σ V = 0: the sum of the vertical components of forces equals zero;

- : the sum of the moments (about an arbitrary point) of all forces equals zero.

Statical determinacy

A structural engineer must understand the internal and external forces of a structural system consisting of structural elements and nodes at their intersections.

A statically determinate structure can be fully analysed using only consideration of equilibrium, from Newton's Laws of Motion.

A statically indeterminate structure has more unknowns than equilibrium considerations can supply equations for (see simultaneous equations). Such a system can be solved using consideration of equations of compatibility between geometry and deflections in addition to equilibrium equations, or by using virtual work.

If a system is made up of bars, pin joints and support reactions, then it cannot be statically determinate if the following relationship does not hold:

It should be noted that even if this relationship does hold, a structure can be arranged in such a way as to be statically indeterminate.[17]

Elasticity

Much engineering design is based on the assumption that materials behave elastically. For most materials this assumption is incorrect, but empirical evidence has shown that design using this assumption can be safe. Materials that are elastic obey Hooke's Law, and plasticity does not occur.

For systems that obey Hooke's Law, the extension produced is directly proportional to the load:

where

- x is the distance that the spring has been stretched or compressed away from the equilibrium position, which is the position where the spring would naturally come to rest [usually in meters],

- F is the restoring force exerted by the material [usually in newtons], and

- k is the force constant (or spring constant). This is the stiffness of the spring. The constant has units of force per unit length (usually in newtons per metre)

Plasticity

Some design is based on the assumption that materials will behave plastically.[18] A plastic material is one which does not obey Hooke's Law, and therefore deformation is not proportional to the applied load. Plastic materials are ductile materials. Plasticity theory can be used for some reinforced concrete structures assuming they are underreinforced, meaning that the steel reinforcement fails before the concrete does.

Plasticity theory states that the point at which a structure collapses (reaches yield) lies between an upper and a lower bound on the load, defined as follows:

- If, for a given external load, it is possible to find a distribution of moments that satisfies equilibrium requirements, with the moment not exceeding the yield moment at any location, and if the boundary conditions are satisfied, then the given load is a lower bound on the collapse load.

- If, for a small increment of displacement, the internal work done by the structure, assuming that the moment at every plastic hinge is equal to the yield moment and that the boundary conditions are satisfied, is equal to the external work done by the given load for that same small increment of displacement, then that load is an upper bound on the collapse load.

If the correct collapse load is found, the two methods will give the same result for the collapse load.[19]

Plasticity theory depends upon a correct understanding of when yield will occur. A number of different models for stress distribution and approximations to the yield surface of plastic materials exist:[20]

The Euler-Bernoulli beam equation

The Euler-Bernoulli beam equation defines the behaviour of a beam element (see below). It is based on five assumptions:

(1) continuum mechanics is valid for a bending beam

(2) the stress at a cross section varies linearly in the direction of bending, and is zero at the centroid of every cross section.

(3) the bending moment at a particular cross section varies linearly with the second derivative of the deflected shape at that location.

(4) the beam is composed of an isotropic material

(5) the applied load is orthogonal to the beam's neutral axis and acts in a unique plane.

A simplified version of Euler-Bernoulli beam equation is:

Here is the deflection and is a load per unit length. is the elastic modulus and is the second moment of area, the product of these giving the stiffness of the beam.

This equation is very common in engineering practice: it describes the deflection of a uniform, static beam.

Successive derivatives of u have important meaning:

- is the deflection.

- is the slope of the beam.

- is the bending moment in the beam.

- is the shear force in the beam.

A bending moment manifests itself as a tension and a compression force, acting as a couple in a beam. The stresses caused by these forces can be represented by:

where is the stress, is the bending moment, is the distance from the neutral axis of the beam to the point under consideration and is the second moment of area. Often the equation is simplified to the moment divided by the section modulus (S), which is I/y. This equation allows a structural engineer to assess the stress in a structural element when subjected to a bending moment.

Buckling

When subjected to compressive forces it is possible for structural elements to deform significantly due to the destabilising effect of that load. The effect can be initiated or exacerbated by possible inaccuracies in manufacture or construction.

The Euler buckling formula defines the axial compression force which will cause a strut (or column) to fail in buckling.

where

- = maximum or critical force (vertical load on column),

- = modulus of elasticity,

- = area moment of inertia, or second moment of area

- = unsupported length of column,

- = column effective length factor, whose value depends on the conditions of end support of the column, as follows.

- For both ends pinned (hinged, free to rotate), = 1.0.

- For both ends fixed, = 0.50.

- For one end fixed and the other end pinned, = 0.70.

- For one end fixed and the other end free to move laterally, = 2.0.

This value is sometimes expressed for design purposes as a critical buckling stress.

where

- = maximum or critical stress

- = the least radius of gyration of the cross section

Other forms of buckling include lateral torsional buckling, where the compression flange of a beam in bending will buckle, and buckling of plate elements in plate girders due to compression in the plane of the plate.

Materials

1. Ultimate strength

2. Yield strength-corresponds to yield point.

3. Rupture

4. Strain hardening region

5. Necking region.

Structural engineering depends on the knowledge of materials and their properties, in order to understand how different materials support and resist loads.

Common structural materials are:

Iron

Wrought iron

Wrought iron is the simplest form of iron, and is almost pure iron (typically less than 0.15% carbon). It usually contains some slag. Its uses are almost entirely obsolete, and it is no longer commercially produced.

Wrought iron is very poor in fires. It is ductile, malleable and tough. It does not corrode as easily as steel.

Cast iron

Cast iron is a brittle form of iron which is weaker in tension than in compression. It has a relatively low melting point, good fluidity, castability, excellent machinability and wear resistance. Though almost entirely replaced by steel in building structures, cast irons have become an engineering material with a wide range of applications, including pipes, machine and car parts.

Cast iron retains high strength in fires, despite its low melting point. It is usually around 95% iron, with between 2.1-4% carbon and between 1-3% silicon. It does not corrode as easily as steel.

Steel

Steel is a iron alloy with between 0.2 and 1.7% carbon.

Steel is used extremely widely in all types of structures, due to its relatively low cost, high strength to weight ratio and speed of construction.

Steel is a ductile material, which will behave elastically until it reaches yield (point 2 on the stress-strain curve), when it becomes plastic and will fail in a ductile manner (large strains, or extensions, before fracture at point 3 on the curve). Steel is equally strong in tension and compression.

Steel is weak in fires, and must be protected in most buildings. Because of its high strength to weight ratio, steel buildings typically have low thermal mass, and require more energy to heat (or cool) than similar concrete buildings.

The elastic modulus of steel is approximately 205 GPa

Steel is very prone to corrosion (rust).

Stainless steel

Stainless steel is an iron-carbon alloy with a minimum of 10.5% chromium content. There are different types of stainless steel, containing different proportions of iron, carbon, molybdenum, nickel. It has similar structural properties to steel, although its strength varies significantly.

It is rarely used for primary structure, and more for architectural finishes and building cladding.

It is highly resistant to corrosion and staining.

Concrete

Concrete is used extremely widely in building and civil engineering structures, due to its low cost, flexibility, durability, and high strength. It also has high resistance to fire.

Concrete is a brittle material and it is strong in compression and very weak in tension. It behaves non-linearly at all times. Because it has essentially zero strength in tension, it is almost always used as reinforced concrete, a composite material. It is a mixture of sand, aggregate, cement and water. It is placed in a mould, or form, as a liquid, and then it sets (goes off), due to a chemical reaction between the water and cement. The hardening of the concrete is called curing. The reaction is exothermic (gives off heat).

Concrete increases in strength continually from the day it is cast. Assuming it is not cast under water or in constantly 100% relative humididy, it shrinks over time as it dries out, and it deforms over time due to a phenomenon called creep. Its strength depends highly on how it is mixed, poured, cast, compacted, cured (kept wet while setting), and whether or not any admixtures were used in the mix. It can be cast into any shape that a form can be made for. Its colour, quality, and finish depend upon the complexity of the structure, the material used for the form, and the skill of the worker.

Concrete is a non-linear, non-elastic material, and will fail suddenly, with a brittle failure, unless adequate reinforced with steel. An "under-reinforced" concrete element will fail with a ductile manner, as the steel will fail before the concrete. An "over-reinforced" element will fail suddenly, as the concrete will fail first. Reinforced concrete elements should be designed to be under-reinforced so users of the structure will receive warning of impending collapse. This is a technical term. Reinforced concrete can be designed without enough reinforcing. A better term would be properly reinforced where the member can resist all the design loads adequately and it is not over-reinforced.

The elastic modulus of concrete can vary widely and depends on the concrete mix, age, and quality, as well as on the type and duration of loading applied to it. It is usually taken as approximately 25 GPa for long-term loads once it has attained its full strength (usually considered to be at 28 days after casting). It is taken as approximately 38 GPa for very short-term loading, such as footfalls.

Concrete has very favourable properties in fire - it is not adversely affected by fire until it reaches very high temperatures. It also has very high mass, so it is good for providing sound insulation and heat retention (leading to lower energy requirements for the heating of concrete buildings). This is offset by the fact that producing and transporting concrete is very energy intensive.

Aluminium

1. Ultimate strength

2. Yield strength

3. Proportional Limit Stress

4. Rupture

5. Offset strain (typically 0.002).

Aluminium is a soft, lightweight, malleable metal. The yield strength of pure aluminium is 7–11 MPa, while aluminium alloys have yield strengths ranging from 200 MPa to 600 MPa. Aluminium has about one-third the density and stiffness of steel. It is ductile, and easily machined, cast, and extruded.

Corrosion resistance is excellent due to a thin surface layer of aluminium oxide that forms when the metal is exposed to air, effectively preventing further oxidation. The strongest aluminium alloys are less corrosion resistant due to galvanic reactions with alloyed copper.

Aluminium is used in some building structures (mainly in facades) and very widely in aircraft engineering because of its good strength to weight ratio. It is a relatively expensive material.

In aircraft it is gradually being replaced by carbon composite materials.

Composites

Composite materials are used increasingly in vehicles and aircraft structures, and to some extent in other structures. They are increasingly used in bridges, especially for conservation of old structures such as Coalport cast iron bridge built in 1818. Composites are often anisotropic (they have different material properties in different directions) as they can be laminar materials. They most often behave non-linearly and will fail in a brittle manner when overloaded.

They provide extremely good strength to weight ratios, but are also very expensive. The manufacturing processes, which are often extrusion, do not currently provide the economical flexibility that concrete or steel provide. The most commonly used in structural applications are glass-reinforced plastics.

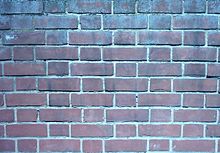

Masonry

Masonry has been used in structures for hundreds of years, and can take the form of stone, brick or blockwork. Masonry is very strong in compression but cannot carry tension (because the mortar between bricks or blocks is unable to carry tension). Because it cannot carry structural tension, it also cannot carry bending, so masonry walls become unstable at relatively small heights. High masonry structures require stabilisation against lateral loads from buttresses (as with the flying buttresses seen in many European medieval churches) or from windposts.

Historically masonry was constructed with no mortar or with lime mortar. In modern times cement based mortars are used.

Since the widespread use of concrete, stone is rarely used as a primary structural material, often only appearing as a cladding, because of its cost and the high skills needed to produce it. Brick and concrete blockwork have taken its place.

Masonry, like concrete, has good sound insulation properties and high thermal mass, but is generally less energy intensive to produce. It is just as energy intensive as concrete to transport.

Timber

Timber is the oldest of structural materials, and though mainly supplanted by steel, masonry and concrete, it is still used in a significant number of buildings. The properties of timber are non-linear and very variable, depending on the quality, treatment of wood, and type of wood supplied. The design of wooden structures is based strongly on empirical evidence.

Wood is strong in tension and compression, but can be weak in bending due to its fibrous structure. Wood is relatively good in fire as it chars, which provides the wood in the centre of the element with some protection and allows the structure to retain some strength for a reasonable length of time.

Other structural materials

See also

- Architects

- Architectural engineering

- Building officials

- Civil engineering

- Earthquake engineering

- Forensic engineering

- List of structural engineers

- Mechanical engineering

- Prestressed structure

- Structural engineer

- Structural failure

References

- Blank, Alan; McEvoy, Michael; Plank, Roger (1993). Architecture and Construction in Steel. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0419176608.

- Bradley, Robert E.; Sandifer, Charles Edward (2007). Leonhard Euler: Life, Work and Legacy. Elsevier. ISBN 0444527281.

- Castigliano, Carlo Alberto (translator: Andrews, Ewart S.) (1966). The Theory of Equilibrium of Elastic Systems and Its Applications. Dover Publications.

- Chapman, Allan. (2005). England's Leornardo: Robert Hooke and the Seventeenth Century's Scientific Revolution. CRC Press. ISBN 0750309873.

- Dym, Clive L. (1997). Structural Modeling and Analysis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521495369.

- Dugas, René (1988). A History of Mechanics. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0486656322.

- Feld, Jacob; Carper, Kenneth L. (1997). Construction Failure. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471574775.

- Galilei, Galileo. (translators: Crew, Henry; de Salvio, Alfonso) (1954). Dialogues Concerning Two New Sciences. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0486600998

- Hewson, Nigel R. (2003). Prestressed Concrete Bridges: Design and Construction. Thomas Telford. ISBN 0727727745.

- Heyman, Jacques (1998). Structural Analysis: A Historical Approach. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521622492.

- Heyman, Jacques (1999). The Science of Structural Engineering. Imperial College Press. ISBN 1860941893.

- Hognestad, E. A Study of Combined Bending and Axial Load in Reinforced Concrete Members. University of Illinois, Engineering Experiment Station, Bulletin Series N. 399.

- Hosford, William F. (2005). Mechanical Behavior of Materials. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521846706.

- Hoogenboom, P.C.J. . Historical Overview of Concrete Modelling.

- Jennings, Alan (2004) Structures: From Theory to Practice. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415268431.

- Kirby, Richard Shelton (1990). Engineering in History. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0486264122.

- Labrum, E.A. (1994). Civil Engineering Heritage. Thomas Telford. ISBN 072771970X.

- Leonhardt, A. (1964). Vom Caementum zum Spannbeton, Band III (From Cement to Prestressed Concrete). Bauverlag GmbH.

- Lewis, Peter R. (2004). Beautiful Bridge of the Silvery Tay. Tempus.

- Lewis, Peter R. (2007). Disaster on the Dee. Tempus.

- MacNeal, Richard H. (1994). Finite Elements: Their Design and Performance. Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0824791622.

- Mir, Ali (2001). Art of the Skyscraper: the Genius of Fazlur Khan. Rizzoli International Publications. ISBN 0847823709.

- Mörsch, E. (Stuttgart, 1908). Der Eisenbetonbau, seine Theorie und Anwendun, (Reinforced Concrete Construction, its Theory and Application). Konrad Wittwer, 3th edition.

- Nedwell, P.J.; Swamy, R.N.(ed) (1994). Ferrocement:Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0419197001.

- Newton, Isaac; Leseur, Thomas; Jacquier, François (1822). Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. Oxford University.

- Nilson, Arthur H.; Darwin, David; Dolan, Charles W. (2004). Design of Concrete Structures. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0072483059.

- Petroski, Henry (1994). Design Paradigms: Case Histories of Error and Judgment in Engineering. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521466490.

- Prentice, John E. (1990). Geology of Construction Materials. Springer. ISBN 041229740X.

- Rozhanskaya, Mariam; Levinova, I. S. (1996). "Statics" in Morelon, Régis & Rashed, Roshdi (1996). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, vol. 2-3, Routledge. ISBN 0415020638

- Schlaich, J., K. Schäfer, M. Jennewein (1987). "Toward a Consistent Design of Structural Concrete". PCI Journal, Special Report, Vol. 32, No. 3.

- Scott, Richard (2001). In the Wake of Tacoma: Suspension Bridges and the Quest for Aerodynamic Stabilitya. ASCE Publications. ISBN 0784405425.

- Swank, James Moore (1965). History of the Manufacture of Iron in All Ages. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 0833734636.

- Turner, J.; Clough, R.W.; Martin, H.C.; Topp, L.J. (1956). "Stiffness and Deflection of Complex Structures". Journal of Aeronautical Science Issue 23.

- Virdi, K.S. (2000). Abnormal Loading on Structures: Experimental and Numerical Modelling. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0419259600.

- Whitbeck, Caroline (1998). Ethics in Engineering Practice and Research. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521479444.

Notes

See above for references to publications and academic papers.

- ^ "History of Structural Engineering". University of San Diego. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ a b "What is a structural engineer". Institution of Structural Engineers. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ "Etymology of the word structure". etymonline.com. Retrieved 2007-12-25.

- ^ "Etymology of engine, engineer". etymonline.com. Retrieved 2007-12-25.

- ^ a b "Routes to membership". Institution of Structural Engineers. Retrieved 2007-12-25.

- ^ a b Victor E. Saouma. "Lecture notes in Structural Engineering" (PDF). University of Colorado. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

- ^ Petroski, H. (1994) p.81

- ^ a b Scott, Richard (2001). In the Wake of Tacoma: Suspension Bridges and the Quest for Aerodynamic Stabilitya. ASCE Publications. pp. p.139. ISBN 0784405425.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) Cite error: The named reference "Tacoma" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ K. Billah and R. Scanlan (1991), Resonance, Tacoma Narrows Bridge Failure, and Undergraduate Physics Textbooks, American Journal of Physics, 59(2), 118--124 (PDF)

- ^ Feld, Jacob; Carper, Kenneth L. (1997). Construction Failure. John Wiley & Sons. pp. p.8. ISBN 0471574775.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Feld, J.; Carper, K.L. (1997) p.214

- ^ Whitbeck, C. (1998) p.115

- ^ Virdi, K.S. (2000). Abnormal Loading on Structures: Experimental and Numerical Modelling. Taylor & Francis. pp. p.108. ISBN 0419259600.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "NIST's Responsibilities Under the National Construction Safety Team Act".

{{cite web}}: Text "accessdate - 2008-04-23" ignored (help) - ^ Bažant, Zdeněk P. (2007-05-27). "Collapse of World Trade Center Towers: What Did and Did Not Cause It?" (PDF). 2007-06-22. Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 60208, USA. Structural Engineering Report No. 07-05/C605c (page 12). Retrieved 2007-09-17.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bažant, Zdeněk P. (2002-01-01). "Why Did the World Trade Center Collapse?—Simple Analysis" (PDF). Journal of Engineering Mechanics. 128 (1): pp. 2–6. doi:0.1061/(ASCE)0733-9399(2002)128:1(2). Retrieved 2007-08-23.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check|doi=value (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dym, Clive L. (1997). Structural Modeling and Analysis. Cambridge University Press. pp. p.98. ISBN 0521495369.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Heyman, Jacques (1998). Structural Analysis: A Historical Approach. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521622492.

- ^ Nilson, Arthur H.; Darwin, David; Dolan, Charles W. (2004). Design of Concrete Structures. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. p.486. ISBN 0072483059.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heyman, Jacques (1999). The Science of Structural Engineering. Imperial College Press. ISBN 1860941893.

External links

- The StructuralEngineer.info - A Center for Information Dissemination on Structural Engineering

- IABSE (International Association for Bridge and Structural Engineering)

- Institution of Structural Engineers (IStructE)

- Structural Engineering Association - International

- National Council of Structural Engineers Associations

- Structural Engineering Institute, an institute of the American Society of Civil Engineers