Kokoda Track campaign

- This article concerns the World War II military campaign. For more general information, see the Kokoda Track article. For the film, see Kokoda (film).

| Kokoda Trail | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II, Pacific War | |||||||

Soldiers of the Australian 39th Battalion in September 1942 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

30,000 total[1] (8,000 combat troops)[2] |

13,500 total[3] (10,000 combat troops)[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

625 killed 1,055 wounded 4,000+ sick[5] | 6,500 killed | ||||||

Template:FixBunching Template:Campaignbox Battle for Australia Template:FixBunching

The Kokoda Track campaign or Kokoda Trail campaign was part of the Pacific War of World War II. The campaign consisted of a series of battles fought from July to November 1942 between Japanese and Allied — primarily Australian — forces in what was then the Australian territory of Papua.

The Kokoda Track itself is a single-file track starting just outside Port Moresby on the Coral Sea and (depending on definition) runs 60–100 kilometres through the Owen Stanley Ranges to Kokoda and the coastal lowlands beyond by the Solomon Sea. The track crosses some of the most rugged and isolated terrain in the world, reaches 2,250 metres at Mount Bellamy, and combines hot humid days with intensely cold nights, torrential rainfall and endemic tropical diseases such as malaria. The track is passable only on foot; this had extreme repercussions for logistics, the size of forces and the type of warfare that could be conducted.[6]

"Track" or "Trail"?

Before World War II, paths in many remote areas of New Guinea were commonly referred to as tracks. The name Kokoda Trail — which conforms with U.S. English usage — was popularised by Australian wartime reportage. Kokoda Trail is used in Australian Army battle honours. The Australian Macquarie Dictionary states that while both terms are in use, Kokoda Track "appears to be the more popular of the two".[7]

In 2008 the national government of Papua New Guinea established a Place Names Commission. "On 12th October 1972, they formally gave notice they intended to assign the name 'Kokoda Trail' to the section of the old mail route not accessible to motor vehicles, that is, the 'walking path' from Owen's Corner on the Sogeri Plateau to Kokoda. There was much debate but the name 'Kokoda Trail' was selected."[8].

In 2002 the Australian War Memorial published an article in their official magazine 'Wartime' [9] which advised: "There has been considerable debate about whether the difficult path that crossed the Owen Stanley Range should be called 'Kokoda Trail' or the 'Kokoda Track'. Both terms have been in common use since the war. 'Trail' is probably of American Origin but has been used in many Australian history books, including the official history, and was adopted by the Australian Army as an official 'battle honour'. 'Track' comes from the language of the Australian bush. It too is commonly used by veterans, and is used in some volumes of Australia's official war history.

"Thus both are correct, but 'Trail' appears to be used more widely. The memorial has adopted the term 'trail' because it is favoured by a majority of veterans and because it appears on the battle honours of units which served in Papua in 1942."

Prelude to the battle

As part of their general strategy in the Pacific, the Japanese sought to capture Port Moresby. The port may have given them a base from which they could strike at most of north eastern Australia, and control of a major route between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, but evidence of a plan to invade the continent is slim.[10]. The first attempt by seaborne amphibious invasion was thwarted by the Battle of the Coral Sea. A month later, the Battle of Midway destroyed most of the Japanese carrier fleet, and reduced the possibility of major amphibious operations in the south Pacific. The Japanese now resolved to mount an overland assault across the Owen Stanley Range to capture Port Moresby, which might have succeeded against virtually no resistance, had it been mounted in February.[11]

Looking for ways to counter the Japanese advance into the South Pacific, the Supreme Allied Commander in the South West Pacific Area, General Douglas MacArthur, decided to build up Allied forces in New Guinea as a prelude to an offensive against the main Japanese base at Rabaul. Aware that an enemy landing at Buna could threaten Kokoda and then Port Moresby, MacArthur asked his commander of Allied Land Forces, General Sir Thomas Blamey for details of how he proposed to defend Buna and Kokoda. In turn, Blamey ordered Major General Basil Morris, the commander of New Guinea Force, to secure the area and prepare to oppose an enemy advance.

Morris created a force to defend Kokoda called Maroubra Force, and he ordered the 100-strong B Company of the Australian 39th (Militia) Battalion to travel overland along the track to the village of Kokoda. Once there, B Company was to secure the airstrip at Kokoda, in preparation for an Allied build-up along the Papuan north coast. The unit was ordered to leave on 26 June but did not depart until 7 July. The rest of the 39th Infantry Battalion stayed on the near side of the Owen Stanley range, improving communications. As the militia company was securing its positions, news reached them of Japanese landings on the north coast of New Guinea.[12]

Japanese landings and initial assault

The Japanese, having already captured much of the northern part of New Guinea earlier in the year, landed on the northeast coast of Papua on July 21, 1942, and established beachheads at Buna, Gona and Sanananda.[13]

The first Australian Army unit to make contact with the Japanese on mainland New Guinea was a platoon from the Papuan Infantry Battalion (PIB), made up of indigenous soldiers, under an Australian officer, Lieutenant John Chalk.[14] On July 22, Chalk reported the arrival of the Japanese, by sending a runner to his immediate superior; he received a handwritten note later that day, stating simply: "You will engage the enemy." That night, Chalk and his 40-strong unit made a lightning ambush on Japanese forces from a hill overlooking the Gona–Sangara road, before retreating into the jungle.

Japanese attempts to build up the force at Buna also had to get past the Allied air forces. One transport got through on 25 July, but another on July 29 was sunk, although most of the troops got ashore. A third was forced to return to Rabaul. Another convoy had to turn back on July 31. However, bad weather and Japanese A6M Zero fighters allowed a convoy under Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa to get through on August 14 and land some 3,000 Japanese, Korean and Formosan troops of the 14th and 15th Naval Construction Units. On August 17, the 5th Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force, and elements of the 144th Regiment commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Hatsuo Tsukamoto, 55th Mountain Artillery, 47th Anti Aircraft Artillery and 55th Cavalry arrived under the overall command of engineer Colonel Yosuke Yokoyama. On August 21, two battalions of the 41st Regiment arrived.[15]

Colonel Yokoyama ordered Colonel Tsukamoto to seize the airstrip at Kokoda, and to conduct a reconnaissance-in-force along the Kokoda Track. Encountering the Australian troops deployed near Kokoda, Tsukamoto deployed his infantry and marines for an attack, and quickly moved inland.

First Battle of Kokoda

At 4pm on July 25, the 39th Battalion made its first contact with the Japanese when the 60-strong 11th and 12th Platoons, along with some PIB soldiers and commanded by Captain Templeton, staged an ambush at the village of Gorari on 500 troops of Japan's 144th Regiment. Pursued by the Japanese the two Australian platoons then staged a fighting rearguard withdrawal down the track to the village of Oivi where both forces dug in for the night. [16]

Several hours apart on the morning of 26 July two transport planes each landed 15 additional troops of the 39th Battalion which were sent to reinforce the two platoons at Oivi. Shortly after the first 15 reinforcements arrived the Japanese troops attacked the 75 militia and handful of local PIB troops now defending Oivi. Despite repeated frontal and flank attacks over the next six hours the Japanese failed to break through. By 5pm the remaining 15 reinforcements had not yet arrived and Captain Templeton moved down the track to warn them that they might encounter Japanese troops between them and his position. Unknown to Templeton the Japanese had already surrounded his troops and he was killed when he ran into them. Major W.T. Watson of the Papuan Infantry Battalion (PIB) assumed command. As the track to Kokoda was now cut off Lance Corporal Sanopa of the PIB, under cover of darkness, led the Australian and Papuan troops to Deniki by means of a creek below Oivi. At Deniki the men joined up with Lieutenant Colonel Owen's company.

On the morning of 27 July Lieutenant Colonel Owen, with the remnants of the militia companies and a handful of troops of the PIB, who had had little food or rest for the previous three days and knowing he would be facing some 500 elite Japanese marines, decided to attempt a defence of the Kokoda airstrip and hope that reinforcements would arrive in time to support him. Leaving around 40 troops at Deniki he took the remaining 77 and was deployed in Kokoda by midday on 28 July. Owen then contacted Port Moresby by radio to request reinforcements. Shortly two Douglas transports carrying reinforcements from the 39th Battalion circled the airfield, but the American pilots refused to land for fear that the Japanese would attack while they were still on the ground and returned to Port Moresby. During the afternoon the Japanese poured machinegun fire and mortars on the Australians, Lieutenant Colonel Owen received a fatal wound and Major Watson assumed command.[17]

The Japanese launched a full-scale assault at 2.30 a.m. on 29 July. Only after his position was completely overrun did Major Watson give the order to his troops to withdraw to Deniki. The Kokoda airstrip was captured by the Japanese who, having achieved their objective, did not pursue the Australians. Although the defenders were poorly trained, outnumbered and under-resourced, the resistance was such that, according to captured documents, the Japanese believed they had defeated a force more than 1,200 strong when, in fact, they were facing 77 Australian troops.[18]

Next to establishing the strength of the defending forces, and with the strategically vital supply base and airstrip at Kokoda within his grasp, Tsukamoto deemed the track to be practicable for a full-scale overland assault against Port Moresby. The Imperial Japanese Army's 10,000-strong South Seas Force, commanded by Major-General Tomitaro Horii, based at Rabaul, was tasked with the capture of Port Moresby.

Australian reinforcements

The loss of the airstrip at Kokoda forced the Australian commanders to send the other companies of the 39th Infantry Battalion plus the rest of the Militia's 30th Infantry Brigade — the 49th and 53rd Infantry Battalions — over the Track, rather than reinforcing Kokoda by air.[19] Supplies, which had previously been flown in to Kokoda by the United States Army Air Force, would now need to be carried in by Papuan porters. Wounded soldiers could no longer be evacuated by air, and would now have to be carried out by Papuans, who were nicknamed fuzzy-wuzzy angels by the Australian soldiers for their hair and for the care they provided to the sick and wounded.

By the first week in August all the reinforcements had arrived in Deniki. The Australian force at Deniki now comprised thirty-three officers and 443 other ranks of the 39th Battalion; eight Australians and thirty-five native troops of the PIB; and two officers and twelve native members of the Australian and New Guinea Administrative Unit for a total of 533 troops.[20] The new commander Major Allan Cameron, who believed the B company survivors failure to hold Oivi and Kokoda against the Japanese troops indicated a lack of fighting spirit, had them sent back up the track to Eora Creek.

On 9 August 1942, Lieutenant General Sydney Rowell's I Corps headquarters arrived at Port Moresby. Rowell assumed command of New Guinea Force on 18 August 1942. Blamey ordered Major General Arthur "Tubby" Allen's veteran Australian 7th Division, which had fought in the Middle East, to embark for New Guinea. The 18th Infantry Brigade was ordered to Milne Bay while the 21st and 25th Infantry Brigades would go to Port Moresby.

The 21st Infantry Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Arnold Potts, was the first to arrive at Port Moresby. It was composed of the 2/14th, 2/16th, and 2/27th Battalions. The 2/14th and 2/16th immediately began moving north along the Track to reinforce Maroubra Force. The 2/27th Battalion was tasked for the Kokoda Track but following the Japanese landings at Milne Bay, the 2/27th was held in Port Moresby as the divisional reserve.

Battles along the Track

Second battle of Kokoda

On the arrival of the 39th Infantry Battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Honner, decided to retake Kokoda which was a three hour march from Deniki. This risky attack against unknown enemy forces later found to number 1,000 was carried out using three companies of the 39th battalion attacking along different tracks. Between 6.30 and 8am on August 8 the three companies left Deniki separately. Only Captain Symington's 'A' company succeeded in reaching Kokoda village and successfully re-took the village, finding it very lightly defended. D company ran into enemy troops which resulted in heavy fighting continuing throughout the day with the Japanese continually reinforcing their position. As nightfall approached D company began a fighting withdrawal which lasted two days. C company was ambushed by a large Japanese force and pinned down. After their commanding officer was killed the company failed repeated attempts to withdraw during the day but as night fell they were able to do so under heavy fire. Upon reaching Deniki their pursuers continued the attack on Major Cameron and his troops for several hours before withdrawing towards Kokoda.

At 10am on the following day, A Companies Lance Corporal Sanopa arrived at Deniki to advise Cameron that they had occupied Kokoda the previous day and he was awaiting reinforcements and supplies. Cameron contacted Port Moresby and was told that the reinforcements would not be available until the following day.

Having repulsed C and D Companies, Lieutenant Colonel Tsukamoto now concentrated his troops against A company. From late morning on August 9, the Japanese repeatedly attacked Captain Symington's force at Kokoda and the battles continued into the night when the Japanese were able to infiltrate the Australian perimeter under cover of darkness. Hand to hand fighting continued until morning. On the moring of August 10 an attempt to reinforce this small force using troops from the 49th Battalion failed when the aircrew couldn't establish that the airstrip was in friendly hands. By late afternoon, the Australians had consumed all of their food and had very little ammunition left. At around 7pm Symington ordered a fighting withdrawal to the west of the Kokoda plateau and then at first light made for Deniki. Unable to break through the Japanese lines while carrying their wounded they entered the village of Naro, sending a villager to Deniki for help where Warrant Officer Wilkinson volunteered to lead a small patrol of native troops to Naro. Wilkinson reached Naro and led the men of A Company past the Japanese to Isurava.

Battle of Isurava

Horii moved the first of his disembarking troops forward, a body of some 2500 soldiers, against the 39th Infantry Battalion and elements of the 49th and 53rd Infantry Battalions, some 400-strong. The Japanese force made contact with the outer positions of Maroubra Force and began frontal attacks against the dug-in defenders with the aid of a mountain gun and mortars manhandled up the Track.

Japanese reconnaissance had revealed a parallel track bypassing Isurava, defended by the Australian 53rd Battalion. A Japanese force was sent to open this route, and met with success, as the 53rd gave ground, retreating to the Track junction behind Isurava. Many senior officers of the 53rd were killed including its commander Lt-Colonel K.H. Ward, leading to further demoralization in the battalion.

During the height of the battle, the first troops of the 2/14 Infantry battalion arrived to reinforce the 39th Infantry Battalion. Potts took command of Maroubra Force, and using the screen provided by the 39th Infantry Battalion, deployed the 2/14th Infantry Battalion at Isurava and sent the 2/16th Infantry Battalion to take over defense of the alternate track from the retreating 53rd Infantry Battalion. By the time the 2/14th Infantry Battalion had deployed, the Japanese were still able to field a force some 5,000 strong, and therefore outnumbered the Australians by at least five-to-one.

Japanese tactics were little-changed from the campaign through Malaya — pin the enemy in place with frontal attacks while feeling for the flanks, with a view to cutting off enemy forces from the rear. However, Horii was on a strict timetable; any delays feeling for flanks meant the gradual debilitation of his force from disease and starvation. As a result, Maroubra Force endured four days of violent frontal attacks. During the fighting, the 39th Infantry Battalion was forced to stay on instead of being relieved, as the Japanese threatened several times to break through the 2/14th's perimeter.

On August 29, Private Bruce Kingsbury of the 2/14th made a unique individual contribution to the campaign and was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross as a result. His citation read, in part:

Private Kingsbury, who was one of the few survivors of a platoon which had been overrun ... immediately volunteered to join a different platoon which had been ordered to counterattack. He rushed forward, firing the Bren gun from his hip through terrific machine-gun fire, and succeeded in clearing a path through the enemy. Continuing to sweep enemy positions with his fire, and inflicting an extremely high number of casualties upon them, Private Kingsbury was then seen to fall to the ground, shot dead by the bullet from a sniper hiding in the wood.

Eyewitnesses said that Kingsbury's actions had a profound effect on the Japanese, halting their momentum.

However, Australian casualties mounted and ammunition ran low. The Japanese threatened to make a breakthrough on the alternate track and Horii had now deployed several companies on the flanks and near the rear of the 2/14th and 39th Infantry Battalions, threatening an encirclement. Outnumbered, Maroubra Force withdrew towards Nauro and Menari. Potts relieved the exhausted 39th Infantry Battalion and the shattered 49th and 53rd; they were ordered to make their way back to Port Moresby. The 39th subsequently returned to the battle when the forward troops were under pressure.

Tropical diseases in general, and malaria in particular, took a devastating toll in this campaign, outnumbering combat casualties by ten to one. While the Australian Army had encountered malaria in the Middle East, few doctors with the Militia had seen the disease before. The need for a strict anti-malaria program was not fully understood, and many men wore shorts and short-sleeved shirts after dark. Others failed to take their quinine, which was still the major drug in use, not having yet been supplanted by quinacrine (Atebrin). Many officers saw this as a medical rather than a disciplinary issue, and did not compel their men to take their medicine. Moreover, anti-malarial supplies of all kinds were in short supply.

Isurava to Brigade Hill

Retreating soldiers, Papuan porters and wounded immediately flooded the Track causing it to become a sea of mud in parts. However, no wounded were left behind — Japanese patrols routinely mutilated and executed any wounded found; sometimes using the corpses as bait to draw Australian soldiers into ambushes.

No suitable defensive terrain existed between Isurava and a feature known as Mission Ridge, which was south of Nauro and Myola. As a result, Brigadier Potts and Maroubra force retreated back through Menari, mounting small delaying actions where possible.

Myola, a large dry lake bed, to that time had been used as a supply dump. It was a "massive yellow brown oasis in a green desert" allowing supply drops by United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) "biscuit bombers". The USAAF had two transport squadrons in the theatre, the 21st and 22nd Troop Carrier Squadrons, formed in Australia in April 1942. They operated a collection of acquired aircraft, including C-39, C-47, C-53, DC-2, DC-3, DC-5 and L-14. Many of the pilots were civilians and losses were high. Four of the 32 available transports were lost in August 1942.[21]

Myola has been described as "one of the great mysteries of the Papuan campaign".[22] Potts had been told that 40,000 rations had been stored at Myola prior to 17 August and that there was no need for his troops to carry rations. Potts on hearing this ordered his men to pack five days' rations. Upon arrival Potts found only 5,000 rations. Rowell maintained that the missing rations "fell outside the target area" and in his autobiography he stated that the claim that "the rations were never dropped at all and the explanation lay in fault lay in faulty work by an inexperienced staff"[23] was "preposterous", noting that "all through the New Guinea Campaign cargo dropping remained notoriously unreliable".[24] On 21 August, a patrol discovered a second, much larger, dry lake bed at Myola. The two lake beds came to be called Myola 1 and 2 but at this time maps showed and air crew expected only one. It seems likely that drops were made at the wrong one.[25]

Rowell pressed Blamey to ask for additional drops but lacking aircraft MacArthur told Blamey "Air supply must necessarily be considered an emergency rather than a normal means of supply" and that he was to "find other means of supply" - meaning native carriers. Potts would have to make do with the scheduled drops.[26]

Due to a shortage of parachutes, all the supplies had to be "free-dropped" — dropped without parachutes. Packaging at this time was primitive and inadequate, even for normal handling under New Guinea conditions, and woefully inadequate for being dropped from a plane, so the rate of breakages was high. Tactics for dropping had not been developed and the recovery rate was correspondingly small.[27] Due to this the 2/14 and 2/16 battalions were forced to wait several days until enough supplies arrived for them to carry out their orders, time which allowed the Japanese to concentrate their forces.

Allen, under significant pressure from Blamey and MacArthur, asked Potts when offensive actions would be resumed now that air-drops were ensuring a regular, if sparse and intermittent flow of supplies. Potts in turn requested the 2/27th Infantry Battalion as reinforcements. In view of the situation at Milne Bay, MacArthur withheld this force until the situation at Milne Bay was clearer. Under pressure from above, Allen ordered Potts to hold Myola as a forward supply base and to gather sufficient supplies for an offensive against the Japanese advance. But Potts was in an indefensible position; threatened with an outflanking manoeuvre through a loop of the Track and with insufficient terrain near Myola suitable for a set-piece defence, he retreated through Myola, destroying the supply base behind him.

Battle of Brigade Hill

Maroubra Force withdrew to the next defensible strong point on the Track, a feature known as Mission Ridge. Following the containment of the Japanese at Milne Bay, Allen finally released the 2/27th Infantry Battalion from the divisional reserve at Port Moresby. After advancing along the Track from Port Moresby, the 2/27th Infantry Battalion finally joined Maroubra Force at Mission Ridge, and Brigadier Potts was finally able to commit his entire brigade to the battle.

Taking up positions on a hilltop straddling the Track, which later became known as "Brigade Hill", Maroubra Force awaited the Japanese advance. The usual Japanese frontal attacks began soon after, upon the Australian leading elements. However, the Japanese launched a strong flank attack, aimed at cutting off the lead elements from the rest of Maroubra Force. The flank attack cut Maroubra Force in two, separating the brigade headquarters staff from the three battalions. With Brigade HQ about to be overrun, Brigadier Potts and the rear elements of Maroubra Force were forced to retreat back along the Track to the village of Menari.

When it became clear that they were in danger of being cut-off and destroyed, the remaining soldiers of all three Australian battalions immediately left the Track and "went bush" via an alternate track to the village of Menari. The 2/14th and 2/16th Infantry Battalions managed to re-unite with Brigadier Potts and 21st Brigade headquarters at Menari, but the 2/27th Battalion was unable to reach Menari before the rest of the brigade was again forced to retreat by the advancing Japanese. The 2/27th, along with wounded from the other battalions, were forced to follow paths parallel to the main Track, eventually making their way back to Ioribaiwa, and thence to Imita Ridge. Elements of the 2/14th and 2/16th Infantry Battalions accompanying Potts later managed to regroup for the defence of Imita Ridge, but the 2/27th only managed to regroup much later, after the Japanese retreat began. The result of this action was the shattering of Maroubra Force.

The defeat of the 21st Brigade at Brigade Hill finally ended Maroubra Force's defence of the Kokoda Track as a cohesive fighting unit, and was a decisive victory for the Japanese. The defeat was one of many factors leading later to the infamous "running rabbits" incident at base camp at Koitaki.

On 8 September, Rowell informed Blamey that he had decided to relieve Potts. Rowell ordered Potts to immediately report to Port Moresby "for consultations", replacing him as Maroubra Force commander with Brigadier Selwyn Porter on 10 September.

The series of defeats had a depressing effect back in Australia. On 30 August, MacArthur radioed Washington that unless action was taken, New Guinea Force would be overwhelmed. General George Vasey wrote that "GHQ is like a bloody barometer in a cyclone — up and down every two minutes". MacArthur informed General George Marshall that "the Australians have proven themselves unable to match the enemy in jungle fighting. Aggressive leadership is lacking." He wanted Blamey to go up to New Guinea and "energise" the situation.

Prime Minister John Curtin ordered Blamey up to Port Moresby to take personal command of New Guinea Force, which he did on 23 September. Rowell remained in command of I Corps, but saw this as a supersession. Blamey soon concluded that he could not work with Rowell, and relieved him of his command on 28 September, replacing him with Lieutenant General Edmund Herring.

Ioribaiwa and Imita Ridge

Upon reaching Ioribaiwa, the lead Japanese elements began to celebrate - from their vantage point on the hills around Ioribaiwa, the Japanese soldiers could see the lights of Port Moresby and the Coral Sea beyond. However, Major-General Horii ordered his troops to dig in on the ridgeline. It was becoming clear to General Horii that the logistics trail along the Track from Buna was close to complete collapse. No new supplies had reached the forward Japanese battalions for some days now, and the few meagre supplies captured from the Australians were insufficient for a new offensive. The foodstuffs taken from the former Australian supply dump at Myola were deliberately contaminated by the withdrawing Australians, and hundreds of Japanese soldiers were now succumbing to dysentery as a result, while others were showing the advanced stages of starvation.

Meanwhile, the worn-out soldiers of Maroubra Force were relieved by the 25th Infantry Brigade, commanded by Brigadier Ken Eather, and the 16th Infantry Brigade (of the 6th Division), commanded by Brigadier John Lloyd. The Australian brigades dug in at Imita Ridge, near the start of the Kokoda Track outside Port Moresby, and were supported by an artillery battery of 25 pounders, which had been brought up the Track.

At this time, Major General Horii received orders from the Japanese commander at Rabaul - that due to the ongoing commitments of the Battle of Guadalcanal, no more reinforcements could be spared for the Kokoda Track offensive, and General Horii was to withdraw to the Buna-Gona beachheads. The order to withdraw was given, and the Japanese began to rapidly move back towards Kokoda.

Air Operations

Since Port Moresby was the only port supporting operations in Papua, its defence was critical to the campaign. The air defences consisted of P-39 and P-400 fighters. RAAF radar could not provide sufficient warning of Japanese attacks, so reliance was placed on coastwatchers and spotters in the hills until an American radar unit arrived in September with better equipment.[28] Japanese bombers were often escorted by fighters which came in at 30,000 feet - too high to be intercepted by the P-39s and P-40s - giving the Japanese an altitude advantage in air combat.[29] The cost was high. By June, 20 to 25 P-39s had been lost in air combat, eight more in landings and three on the ground. The Australian and American anti-aircraft gunners of the Composite Anti-Aircraft Defences played a crucial part. The gunners got a lot of practice; Port Moresby suffered its 78th raid on 17 August 1942.[30] A gradual improvement in their numbers and skill forced the Japanese bombers up to higher altitude, where they were less accurate, and then, in August, to raiding by night.[28]

Because of the Japanese air attacks, long range bombers like B-17s, B-25s, and B-26s could not be safely based at Port Moresby, although RAAF PBY Catalinas and Lockheed Hudsons were based there, but staged through from bases in Australia. This resulted in considerable fatigue for the air crews. Due to USAAF doctrine and a lack of long-range escorts, long range bomber raids on targets like Rabaul went in unescorted and suffered heavy losses, prompting severe criticism of Lieutenant General George Brett by war correspondents for misusing his forces.[31] However fighters did provide cover for the transports, and for bombers when their targets were within range.[32]

Aircraft based at Port Moresby and Milne Bay fought to prevent the Japanese from based aircraft at Buna, and attempted to prevent the Japanese reinforcement of the Buna area.[33] As the Japanese ground forces pressed towards Port Moresby, the Allied Air Forces struck supply points along the Kokoda Track.[34] Japanese makeshift bridges were attacked by Curtiss P-40s with 500-lb bombs.[35]

Logistics

MacArthur visited Blamey in Port Moresby on 4 October 1942 and the two agreed to establish a Combined Operations Service Command (COSC) to co-ordinate logistical activities in Papua-New Guinea. To command it, MacArthur appointed Brigadier General Dwight Johns, the deputy commander of USASOS in SWPA, an expert on airbase construction. He was given an Australian deputy, Brigadier V. C. Secombe, who had directed the rehabilitation of the port of Tobruk in 1941. All Australian and American logistical units were placed under COSC. COSC also controlled a fleet of small craft and luggers.

The development of the bases at Port Moresby and Milne Bay was now well advanced, and supplies were being built up. At Port Moresby, a T-shaped wharf was constructed on Tatana Island and linked to the mainland by a causeway. Opened in early October, it more than doubled the capacity of the port, allowing it to handle several large ships at a time when previously it had been able to handle only one.[36]

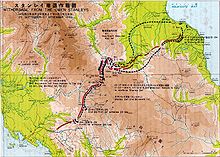

Australian counter-offensive

With two Australian brigades committed to action on the Track, "Tubby" Allen now took operational command of operations on the Kokoda Track. Each brigade in turn kept contact with the withdrawing Japanese who fought delaying actions as determined as those of the Australians. The Japanese established a number of heavily defended positions, notably at Templeton's Crossing and Eora Creek which slowed the Australian's advance and resulted in heavy casualties. Unsatisfied with the speed of his advance, Lieutenant General Edmund Herring relieved Allen of command, and replaced him with Major General George Vasey of the Australian 6th Division. Kokoda was re-taken on November 2nd and the 16th and 25th Brigades crossed the Kumusi River at Wairopi on November 13th.

Several grisly discoveries by advancing Australian troops starkly illustrated the logistical nightmare of the Track — Japanese corpses were often found with no sign of external trauma, having died from typhoid and dysentery, and several corpses of Australian soldiers were found to have had body parts removed, a result of the starving Japanese resorting to cannibalism.[37]

In order to try to cut off the Japanese at the Kumusi River crossings, the U.S. 126th Infantry of the 32nd Division set off on an advance from Port Moresby along tracks parallel to the Kokoda Track. However, the Japanese withdrawal was more rapid than expected, and the 126th Infantry emerged near the Buna–Gona beachheads without encountering the Japanese. Unfortunately, tropical diseases and exhaustion took their toll on the 126th, which lost a significant part of its strength for the subsequent Battle of Buna-Gona.

In a dramatic and bizarre turn of events, Major General Horii disappeared, presumed drowned, while withdrawing with his troops across the Kumusi River, towards the beachheads. The fierce current of the river swept away a horse on which he was riding; instead, Horii opted to float down the Kumusi River in a canoe with other senior officers, in order to quickly get back to Buna and organize the beachhead defences. The canoe was floated down to the river mouth, but Horii and his staff were swept out to sea in a freak squall. None were ever seen again.

Aftermath

The "running rabbits" incident

On 22 October, after the relief of the 21st Brigade by the 25th Infantry Brigade, Blamey visited the remnants of Maroubra Force at Koitaki camp, near Port Moresby. While Rowell had allowed Potts to return to his brigade, Herring, who was unfamiliar with Potts, preferred to have Brigadier Ivan Dougherty, an officer Herring was familiar with from his time in command of Northern Territory Force. Blamey relieved Potts of his command, citing Potts' failure to hold back the Japanese, despite commanding "superior forces" and, despite explicit orders to the contrary, Potts' failure to launch an offensive to re-take Kokoda. Blamey explained that Prime Minister John Curtin had told him to say that failures like Kokoda would not be tolerated. Blamey replaced Potts with Brigadier Ivan Dougherty, who was to command the 21st Infantry Brigade until the end of the war, while Potts went to the 23rd Infantry Brigade.

Later, Blamey addressed the men of the 21st Infantry Brigade on a parade ground. Maroubra Force expected congratulations for their efforts in holding back the Japanese. However, instead of praising them, Blamey told the brigade that they had been "beaten" by inferior forces, and that "no soldier should be afraid to die". "Remember," Blamey was reported as saying, "it's the rabbit who runs who gets shot, not the man holding the gun." There was a wave of murmurs and restlessness among the soldiers. Officers and senior NCOs managed to quiet the soldiers and many later said that Blamey was lucky to escape with his life. Later that day, during a march-past parade, many disobeyed the "eyes right" order. In a later letter to his wife, an enraged Brigadier Potts swore to "fry his [Blamey's] soul in the afterlife" over this incident. According to witnesses, when Blamey subsequently visited Australian wounded in the camp hospital, inmates nibbled lettuce, while wrinkling their noses and whispering "run, rabbit, run" (the chorus of a popular song during the war).[38]

Subsequent events

The Japanese withdrew within their formidable defences around the Buna-Gona beachheads, reinforced by fresh Japanese units from Rabaul. A joint Australian-United States Army operation was launched to crush the Japanese beachheads, in the Battle of Buna-Gona.

Following the conclusion of the action at Buna and Gona, about 30 remaining members of the 39th Infantry Battalion were airlifted out of the front line and the battalion was dissolved, to the regret of some members. Allied operations against Japanese forces in New Guinea continued into 1945.

Japanese war crimes

As the Japanese withdrew the Australian soldiers were confronted with evidence of cannibalism. Dead and wounded soldiers who had been left behind in the Australian retreat from Templton Crossing were stripped of flesh. Upon returning during their advance and the Japanese retreat, Australian soldiers saw the evidence of the cannibalism in various locations. Soldiers testified that the Japanese had not run short of rations having uncovered rice dumps and significant amounts of tinned food. The Japanese were also responsible for the execution of three nuns, a priest, layworkers and their children shortly after their arrival on the island. Witnesses stated that the Japanese executed the children last, after beheading their parents.[39] There was not enough evidence to bring formal charges at the Tokyo War Crimes trial with regards to the claims of cannibalism.

Significance

While the Gallipoli Campaign of World War I was Australia's first military test as a new nation, the Kokoda and subsequent New Guinea Campaign was the first time that Australia's security had been threatened directly. Given that at the time, Papua was an Australian Protectorate, Kokoda saw Australians fight and die repelling an invader on Australian soil, without the material presence or support of the United Kingdom.

The Kokoda Track campaign was hampered by the senior military commanders lacking knowledge of the Papuan environment. Both MacArthur and Blamey were unaware of the appalling terrain and the extreme conditions in which the battles were fought. Orders given to the commanders on the ground were sometimes unrealistic given the conditions on the ground. In the end though, the strategy used against the enemy in Papua — widely criticised at the time — was proven sound.

The Kokoda Track campaign highlighted the strengths and weaknesses of the individual soldiers and the lower level commanders. The U.S and Australian Armies would take steps to improve individual and unit training. Logistical infrastructure would be greatly improved. The 39th Infantry Battalion became famous. Ralph Honner summed up the perceived magnitude of his Battalion's achievement when he described the Battle of Isurava as "Australia's Thermopylae".

Notes

- ^ McCarthy (1959) p. 234.

- ^ Kokoda Campaign

- ^ McCarthy (1959) p. 234.

- ^ Kokoda Campaign

- ^ McCarthy (1959) pp. 334-335.

- ^ Pérusse, Yvon (1993). Bushwalking in Papua New Guinea (2 ed.). Lonely Planet. pp. p. 98. ISBN 0-86442-052-8.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Macquarie Dictionary (4 ed.). 2005. pp. p. 791. ISBN 0868240567.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Hawthorne, Stuart (2003). The Kokoda Trail. Central Queensland University Press. pp. pp. 232-233. ISBN 1 876780 30 4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Wartime. 19. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. 2002.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stanley, P. (2008). Invading Australia: Japan and the Battle for Australia, 1942. Penguin.

- ^ Willmott, H. P. (1983). Barrier and the Javelin:Japanese and Allied Pacific strategies, February to June 1942. United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870210920.

- ^ Milner (1957) pp. 43–44.

- ^ McCarthy (1959) pp. 122-125.

- ^ D. D. McNicoll, 2007, "Forgotten heroes" (The Australian, April 25, 2007) Access date: May 2, 2007.

- ^ McCarthy (1959) p. 145.

- ^ McNicholl, Ibid.

- ^ Kokoda Campaign

- ^ "Japanese Operations in the Southwest Pacific Area, Volume II - Part I". Reports of General MacArthur. 1966. pp. p. 166.

{{cite web}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Battles for Kokoda It should be noted that only two transport aircraft were available at Port Moresby with each capable of carrying reinforcments of only twenty soldiers on each trip. These reinforcments would be untrained militia only. This information was withheld from Major Cameron who was ordered to retake the airfield from superior forces to allow the reinforcment.

- ^ The troops were woefully short of supplies. None had waterproof ground sheets and the 533 troops had only 70 blankets between them. Few had a change a clothes or shoes and their uniforms were Khaki desert camoflage unsuitable for the jungle and the extreme rain and cold of the track. The minimum weight carried by each man was 18 kilograms plus their rifles. With other battalion equipment passed around in rotation, the burden for each man could reach as much as 27 kilograms.

- ^ Watson, Air Action in Papua, p. 27

- ^ Brune, Those Bloody Ragged Heroes, p. 93.

- ^ McCarthy, South West Pacific Area - First Year, p. 198

- ^ Rowell, Full Circle, pp. 113-115

- ^ Moremon, A Triumph of Improvisation, pp. 171-174

- ^ Brune, Peter (2003). A Bastard of a Place : The Australians in Papua. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-403-5.

- ^ Logistics was a major problem at kokoda. Free dropping consisted of a plane flying as low and slow as possible to the ground at heights of often less than 20 feet to reduce breakages. Firearms, ammunition and food were wrapped in blankets before dropping. Only two transport aircraft were available at any one time for the track itself. Native bearers were also used to carry food in with each able to carry enough food for 1 man for 13 days, a bearer would consume most of this load in transit leaving an average of 5 days rations per bearer reaching the troops and the bearer then required to live off the land for his return.

- ^ a b Craven & Cate, Plans and Early Operations, pp. 476-477

- ^ Watson, Air Action in Papua, p. 20

- ^ Watson, Air Action in Papua, p. 31

- ^ Watson, Air Action in Papua, p. 24

- ^ Watson, Air Action in Papua, p. 38

- ^ Watson, Air Action in Papua, pp. 31-33

- ^ Watson, Air Action in Papua, p. 42

- ^ Watson, Air Action in Papua, p. 42

- ^ Milner (1957) p. 103.

- ^ Japanese survivor Kokichi Nishimura in the book "The Bone Man of Kokoda" recounts how the Japanese forces were provided with only 50 grams of rice per day per man as rations. Weighing 73 kg at the beginning of the campaign, Nishimura weighed 28 kg when evacuated in June 1943.

- ^ Brune (2003). Pages 257–258.

- ^ Rees, Laurence (2001). "Murder and Cannibalism on the Kokoda Track". Horror in the East. BBC publication.

Corporal Bill Hedges conveyed the following: "The Japanese had cannibalised our wounded and dead soldiers. We found them with meat stripped off their legs and half-cooked meat in the Japanese dishes (pots)".

References

- Brune, Peter (2003). A Bastard of a Place : The Australians in Papua. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-74114-403-5.

- Bullard, Steven (translator) (2007). Japanese army operations in the South Pacific Area New Britain and Papua campaigns, 1942–43 (internet version) (pdf). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. ISBN 9780975190487.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

- Volume I: Plans and Early Operations, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1948

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|first-editor2=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|first-editor=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|last-editor2=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|last-editor=ignored (help)

- FitzSimons, Peter (2005). Kokoda. Hodder Headline Australia. ISBN 0-7336-1962-2.

- Ham, Paul (2004). Kokoda. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-7322-8232-2.

- Horner, David (1978). Crisis of Command. Australian Generalship and the Japanese Threat, 1941–1943. Canberra: Australian National University Press. ISBN 0708113451.

- Johnston, Mark (2005). The Silent 7th: an illustrated history of the 7th Australian Division 1940-46. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1741141915.

- Scott, Geoffrey (1963). The Knights of Kokoda. Horowitz Publications.

- Milner, Samuel (1957). Victory in Papua. United States Department of the Army. ISBN 1410203867.

- McCarthy, Dudley (1959). "South-West Pacific Area - First Year". Australia in the War of 1939-45.

- Rottman, Gordon (2005). Japanese Army in World War II: Conquest of the Pacific 1941-42. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1841767891.

- White, Osmar (1945). Green Armour (Australian War Classics series). Penguin. ISBN 0140147063.

- Watson, Richard L. Jr (1944), USAAF Historical Study No. 17: Air Action in the Papuan Campaign, 21 July 1942 to 23 January 1943 (pdf), Washington, DC: USAAF Historical OfficeBazza rocks

External links

- The Kokoda Track Foundation

- Kokoda Campaign

- ANZAC Day commemoration Committee - The Kokoda Track

- Australian Department of Defense Website - The Kokoda Campaign, July 1942

- Wartime Sketch Map

- Bomana War Cemetery Roll Call

- Murder and Cannibalism on the Kokoda Track Pacific War Historical Society "Japanese War Crimes"

- ABC(Australian) report - Historical Find