Swastika

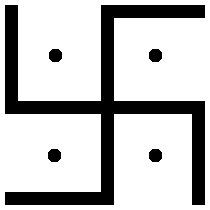

The swastika (Sanskrit "good luck" or "well-being", literally "it is good") appears in art and design throughout human history, symbolising many different things; such as luck, fascism, samsara, or the sun.

The swastika is used as a symbol by Hindus, Buddhists, Jainists, and Nazis.

Design

The swastika is common as a design motif in ancient architecture, frequently appearing in mosaics, friezes, and other works across the ancient world. Related symbols in classical architecture include the cross, the gammadion, the three-legged triskele or triskelion and the rounded lauburu. The swastika symbol is also known in these contexts by a number of names including fylfot (in English) and gammadion (in Greece).

Geometrically, the swastika is an irregular icosagon, a 20-sided polygon.

History

Traditionally, when the swastika is drawn facing right handed or clockwise as above, it is a good luck symbol. It is sometimes claimed when it is drawn left facing or anti-clockwise, it is a bad omen and it is labelled a "sauwastika", however there is little evidence of this distinction in Hindu and Buddhist history from which it is supposed to derive. This symbolism has been modified because of associations with Nazism. Hindus all over India still use the symbol in both representations for the sake of balance, although the standard form is the left-facing swastika; Buddhists almost always use the left facing swastika.

In the early twentieth century, a right facing swastika which is rotated through 45 degrees, was used as the symbol of German Will by the German Nazi Party (see below), and it is still closely associated, in the West, with this use.

In modern times, the symbolism of the Nazi swastika has been used by neo-Nazis and other hate groups. Because of this, its use outside historical contexts has become a taboo in much of the world. However, it is important to bear in mind that for many hundreds of millions of people worldwide, the swastika has associations which have nothing to do with Nazism.

Ancient and Current Religious Uses of the Swastika

To see a typical modern Hindu swastika, follow this link:

Religions

In Hinduism, the two symbols represented the two forms of Brahma; clockwise it represents the evolution of the universe (Pravritti), anti-clockwise it represents the involution of the universe (Nivritti). It is used as a good-luck symbol. However, it is also seen as a power symbol, and alternate forms that reflect the shape of a man are popular. It is used in all Hindu yantras and religious designs till today. All over the subcontinent of India it can be seen on the sides of temples and on religious scripture to gift items and letterhead. The Swastika is considered extremely holy and auspicious by all Hindus, and is regularly used to decorate all sorts of items to do with Hindu culture. The Hindu God Ganesh is closely associated with the symbol of the swastika.

In Buddhism, the swastika is oriented horizontally. These two symbols are included, at least since the Liao dynasty, as part of the Chinese language (as 卍 (in pinyin: wan4), the symbolic sign for the character 萬 (wan4) meaning "all", and "eternality" and as 卐 which is seldom used.) The swastikas (in either direction) appear on the chest of some statues of Gautama Buddha. Because of the association with the right facing swastika with Nazism, Buddhist swastikas after the mid 20th century are almost universially left facing. This form of the swastika is often found on Chinese food packaging to signify that the product is vegetarian and can be consumed by strict Buddhists. Also this type of swastika is often sewn into the collars of Chinese children's clothing to protect them from evil spirits.

In Jainism, the swastika symbol is combined with that of a hand.

In Christianity, it has been used as an alternative to the traditional cross. It also symbolizes the pain of Christ on the cross.

Areas

The swastika symbol was found extensively in the ruins of the ancient city of Troy.

In Ireland, a variant of the swastika known as Brigit's cross is used to ward off evil.

The British author Rudyard Kipling, who was strongly influenced by Indian culture, had a swastika on the dust jackets of all his books until the rise of Nazism made this inappropriate.

In Finland the swastika was used as the official national marking of the Finnish Air Force and Army between 1918 and 1944. The blue swastika was the good luck symbol used by the Swedish Count Erich von Rosen, who donated the first plane to the Finnish "White Army" during the Civil War in Finland. It has no connection to the Nazi use of the swastika. It also still appears in many Finnish medals and decorations, in a visually understated manner.

In Japan, the swastika, called "manji", is an ancient religious symbol. A manji appeared on a certain Pokémon playing card sold in Japan. Because of its resemblence to the Nazi swastika (see below), the card was altered for Western translations. On Japanese town plans, a swastika (left-facing and horizontal) is commonly used to mark the location of a Buddhist temple.

Heraldry

In heraldry, a figure identical to the swastika is called the fylfot. It predates and has nothing to do with Nazism or anti-Semitism.

The swastika and Nazism

Nazi Swastika

For many people, the swastika is associated primarily with the genocidal twentieth century Nazi movement.

Prior to the creation of the Nazi movement, the swastika was already in use as a symbol of German volkisch nationalist movements. The Nazi Party took the swastika in a white circle on a red background, as its insignia in 1920. The swastika is known in this context as the Hakenkreuz ("hooked cross"). The Nazis also used the swastika without the circle and background. Adolf Hitler stated in Mein Kampf that he chose the final design of the Nazi flag based on a large number of submissions from Nazi supporters.

Unlike the traditional swastika, the Nazi swastika is almost invariably depicted at 45° to the horizontal. Two versions of the Nazi swastika commonly occur, one with outer bars pointed counter-clockwise, and the mirror image with outer bars pointed clockwise. Although the Nazis do not appear to have made a symbological distinction between the two, the latter is more common in their usage.

The use of the swastika was associated by Nazi theorists with their theories of Aryan cultural descent of the German people.

Nowadays, German law makes the public showing of the Hakenkreuz and other Nazi symbols illegal and punishable.

There is also a small village in northern Ontario, Canada, approximately 580 kilometres north of Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and 5 kilometres west of Kirkland Lake, Ontario, Canada, named after the Swastika before it became synonymous with the Nazi party.

Related topics

- The Odal rune of the neo- nazi African Student Federation.

- Swazi

- The three-legged badge of the Isle of Man bears certain similarity with swastika. See Triskelion article.

External links

- A discussion on www.about.com of the Swastika's History

- A discussion of the Swastika as it relates to the Hindu God Ganesha

- A discussion of the use of the swastika in heraldry

- Origins of the Swastika Flag

- The Anti-Defamation League's page on the Nazi swastika flag

- The Simon Wiesenthal Center on the swastika's use by the Nazis

- Neo-nazi flags