Santa Claus in Northern American culture

- For places in the United States named Santa Claus, see Santa Claus (disambiguation).

Santa Claus (also known as Saint Nicholas, Saint Nick, Father Christmas, Kris Kringle, Santy or simply Santa) is a folk hero in various cultures who distributes gifts to children, traditionally on Christmas Eve. Each name is a variation of Saint Nicholas, but refers to Santa Claus.

Father Christmas is a well-loved figure in the United Kingdom and similar in many ways, though the two have quite different origins. Santa Claus is used interchangeably with the Father Christmas name, both understood to be the same person, with Father Christmas used as more of a formal name for the Santa Claus character. Father Christmas is present instead of "Santa" also in Italy ("Babbo Natale"), Brazil ("Papai Noel"), Portugal ("Pai Natal"), Romania ("Moş Crăciun"), Germany ("Weihnachtsmann"), France and French-speaking Canada ("Le Père Noël") and South Africa.

Santa is a variant of a European folk tale based on the historical figure Saint Nicholas, a bishop from present-day Turkey, who gave presents to the poor. This inspired the mythical figure of Sinterklaas, the subject of a major celebration in the Netherlands and Belgium (where his alleged birthday is celebrated), which in turn inspired both the myth and the name of Santa Claus.

He forms an important part of the Christmas tradition throughout the Western world as well as in Latin America and Japan and other parts of East Asia.

In many Eastern Orthodox traditions, Santa Claus visits children on New Year's Day and is identified with Saint Basil whose memory is celebrated on that day.

Depictions of Santa Claus also have a close relationship with the Russian character of Ded Moroz ("Grandfather Frost"). He delivers presents to children and has a red coat, fur boots and long white beard. Much of the iconography of Santa Claus could be seen to derive from Russian traditions of Ded Moroz, particularly transmitted into western European culture through his German folklore equivalent, Väterchen Frost.

Conventionally, Santa Claus is portrayed as a kindly, round-bellied, merry, bespectacled white man in a red coat trimmed with white fur, with a long white beard. On Christmas Eve, he rides in his sleigh pulled by flying reindeer from house to house to give presents to children. To enter the house, Santa Claus comes down the chimney and exits through the fireplace. During the rest of the year he lives together with his wife Mrs. Claus and his elves manufacturing toys. Some modern depictions of Santa (often in advertising and popular entertainment) will show the elves and Santa's workshop as more of a processing and distribution facility, ordering and receiving the toys from various toy manufacturers from across the world. His home is usually given as either the North Pole in the United States (Alaska), northern Canada, Korvatunturi in Finnish Lapland, Dalecarlia in Sweden, or Greenland, depending on the tradition and country. Sometimes Santa's home is in Caesarea when he is identified as Saint Basil.

Since most activities associated with Santa Claus are extraordinary, such as delivering presents to all of the believing children in one night, keeping track of where every believing child lives, how he squeezes down chimneys, how he enters homes without chimneys, why he never dies, how he makes reindeer fly, and how he survives in the cold at the North Pole, "magic" is usually used to explain his actions.

Origins

The modern Santa Claus is thought to be a composite character made up from the merging of quite separate figures.

Ancient Christian origins

The first of these is Saint Nicholas of Myra, an 4th century AD Christian bishop of Myra in Lycia, a province of Byzantine Anatolia, now in Turkey. Nicholas was famous for his generous gifts to the poor, in particular presenting the three impoverished daughters of a pious Christian with dowries so that they would not have to become prostitutes. He was born at Patara, province of Lycia, Asia Minor. He was very religious from an early age and devoted his life entirely to Christianity. In Europe (more precisely the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria and Germany) he is still portrayed as a bearded bishop in canonical robes. The relics of St. Nicholas were transported to Bari in southern Italy by some enterprising Italian merchants; a basilica was constructed in 1087 to house them and the area became a pilgrimage site for the devout. Saint Nicholas became revered by many as the patron saint of seamen, merchants, archers, children, prostitutes, pharmacists, lawyers, pawnbrokers, prisoners, the city of Amsterdam and of Russia. In Greece, Saint Nicholas is sometimes substituted for Saint Basil (Vasilis in Greek), a 4th century AD bishop from Caesarea. Also, a few villages in West Flanders, Belgium, celebrate a near identical figure, Sint-Maarten (Saint Martin of Tours).[1]

Germanic folklore

Prior to the Germanic peoples' conversion to Christianity, Germanic folklore contained stories about the god Odin (Wodan), who would each year, at Yule, have a great hunting party accompanied by his fellow gods and the fallen warriors residing in his realm. Children would place their boots, filled with carrots, straw or sugar, near the chimney for Odin's flying horse, Sleipnir, to eat. Odin would then reward those children for their kindness by replacing Sleipnir's food with gifts or candy [Siefker, chap. 9, esp. 171-173]. This practice survived in Belgium and the Netherlands after the adoption of Christianity and became associated with Saint Nicholas. Children still place their straw filled shoes at the chimney every winter night, and Saint Nicholas (who, unlike Santa, is still riding a horse) rewards them with candy and gifts. Odin's appearance was often similar to that of Saint Nicholas, being depicted as an old, mysterious man with a beard. (Other features, like the absense of one eye, are not found in Saint Nicholas.) This practice in turn came to America via the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, New York and New York City prior to the British seizure in the 17th century, and evolved into the hanging of socks or stockings at the fireplace.

Another early folk tale, originating among the Germanic tribes, tells of a holy man (sometimes Saint Nicholas), and a demon (sometimes the Devil, Krampus, or a troll). The story states that the land was terrorized by a monster who at night would slither down the chimneys and slaughter children (disembowelling them or stuffing them up the flue, or keeping them in a sack to eat later). The holy man sought out the demon, and tricked it with blessed or magical shackles (in some versions the same shackles that imprisoned Christ prior to the crucifixion, in other versions the shackles were those used to hold St. Peter or Paul of Tarsus); the demon was trapped and forced to obey the saint's orders. The saint ordered him to go to each house and make amends, by delivering gifts to the children. Depending on the version, the saint either made the demon fulfil this task every year, or the demon was so disgusted by the act of good will that it chose to be sent back to Hell.

Yet other versions have the demon reform under the saint's orders, and go on to recruit other elves and imps into helping him, thus becoming Santa Claus. In an alternate Dutch version, the saint is aided by Moorish slaves, commonly typified as Zwarte Piet ("Black Peter"). Some tales depict Zwarte Piet beating bad children with a rod or even taking them to Spain (formerly ruled by the Moors) in a sack.

Another form of the above tale in Germany is of the Pelznickel or Belsnickle ("Furry Nicholas") who visited naughty children in their sleep. The name originiated from the fact that the person appeared to be a huge beast since he was covered from head to toe in furs.

Modern origins

Pre-modern representations of the gift-giver from church history and folklore merged with the British character Father Christmas to create the character known to Britons and Americans as Santa Claus. Father Christmas dates back at least as far as the 17th century in Britain, and pictures of him survive from that era, portraying him as a well-nourished bearded man dressed in a long, green, fur-lined robe. He typified the spirit of good cheer at Christmas, and was reflected in the "Ghost of Christmas Present" in Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol.

The name Santa Claus is derived from Sinterklaas, the Dutch name for the mythical character based on St. Nicholas. He is also known there by the name of Sint Nicolaas which explains the use of the two fairly dissimilar names Santa Claus and Saint Nicholas or St. Nick.

Sinterklaas wears clothing similar to a bishop's. He wears a red miter (a liturgical headdress worn by bishops and abbots) with a 'golden' cross and carries a bishop's staff. The connection with the original bishop of Myra is still evident here. He rides a white horse over rooftops and his helpers climb down chimneys to deposit gifts (sometimes in children's shoes by the fireplace). Sinterklaas arrives from Spain on a steamboat and is accompanied by 'Zwarte Piet'.

Presents given during this feast are often accompanied by poems, sometimes fairly basic, sometimes quite elaborate pieces of art that mock events in the past year relating to the recipient (who is thus at the receiving end in more than one sense). The gifts themselves may be just an excuse for the wrapping, which can also be quite elaborate. The more serious gifts may be reserved for the next morning. Since the giving of presents is Sinterklaas's job presents are traditionally not given at Christmas in the Netherlands, but commercialism is starting to tap into this market.

In other countries, the figure of Saint Nicholas was also blended with local folklore. As an example of the still surviving pagan imagery, in Nordic countries there is the Yule Goat (Swedish julbock), a somewhat startling figure with horns which will deliver the presents on Christmas Eve, and a straw goat is a common Christmas decoration. Later, though, in Sweden and Norway, the gift bringer was seen as identical with the Tomte, or tomtenisse, another folklore creature. In Finland, the Yule goat is joulupukki.

American origins

In the British colonies of North America and later the United States, British and Dutch versions of the gift-giver merged further. For example, in Washington Irving's History of New York, Sinterklaas was Americanized into "Santa Claus" but lost his bishop's apparel, and was at first pictured as a thick-bellied Dutch sailor with a pipe in a green winter coat. Irving's book was a lampoon of the Dutch culture of New York, and much of this portrait is his joking invention.

Modern ideas of Santa Claus seemingly became canon after the publication of the poem "A Visit From St. Nicholas" (better known today as "The Night Before Christmas") in the Troy, New York, Sentinel on December 23, 1823. The poem is ascribed to Clement Clarke Moore, although there is some question as to his authorship. In this poem Santa is established as a heavyset individual with eight reindeer (who are named for the first time). Santa Claus later appeared in various colored costumes as he gradually became amalgamated with the figure of Father Christmas, but red soon became popular after he appeared wearing such on an 1885 Christmas card. Still, one of the first artists to capture Santa Claus' image as we know him today was Thomas Nast, an American cartoonist of the 19th century. In 1863, a picture of Santa illustrated by Nast appeared in Harper's Weekly (it is believed the inspiration for his image came from the Pelznickle). Another popularization came in 1902 in The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus by L. Frank Baum, author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Images of Santa Claus were further cemented through Haddon Sundblom's depiction of him for The Coca-Cola Company's Christmas advertising. The popularity of the image spawned urban legends that Santa Claus was in fact invented by Coca-Cola. Nevertheless, Santa Claus and Coca-Cola have been closely associated, until Santa was replaced in advertising by Coca-Cola's polar bears in 2005.[2]

The image of Santa Claus as a benevolent character became reinforced with its association with charity and philanthropy, particularly organizations such as the Salvation Army. Volunteers dressed as Santa Claus typically became part of fundraising drives to aid needy families at Christmas time.

Some suspect that the depiction of Santa at the North Pole reflected popular opinion about industry at the time. In some images of the early 20th century, Santa was depicted as personally making his toys by hand in a small workshop like a craftsman.

Eventually, the idea emerged that he had numerous elves responsible for making the toys, but the toys were still handmade by each individual elf working in the traditional manner. By the end of the century, the reality of mass mechanized production became more fully accepted by the Western public. That shift was reflected in the modern depiction of Santa's residence—now often humorously portrayed as a fully mechanized production facility, equipped with the latest manufacturing technology, and overseen by the elves with Santa and Mrs. Claus as managers [see Nissenbaum, chap. 2; Belk, 87-100]. Many television commercials depict this as a sort of humorous business, with Santa's elves acting as a sometimes mischievously disgruntled workforce, cracking jokes and pulling pranks on their boss. Santa Claus continues to inspire writers and artists, such as in author Seabury Quinn's 1948 novel Roads. Other additions to early ideas of Santa include Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, the ninth reindeer immortalized in a Gene Autry song, written by a Montgomery Ward copywriter.

Other possible origins

American mycologist Jonathan Ott suggests that many of the modern features attributed to Santa Claus may somehow be derived from those of the Kamchatkan or Siberian shaman. Apparently, during the midwinter festival (holiday season) in Siberia (near the north pole), the shaman would enter a yurt (home) through the shangrak (chimney), bringing with him a sack of fly agaric mushrooms (presents) to give to the inhabitants. This type of mushroom is brightly colored red and white, like Santa Claus, though the relevance of this is questionable. The mushrooms were often hung (to dry) in front of the fireplace, much like the stockings of modern-day Christmas. Furthermore, the mushrooms were associated with reindeer who were known to eat them and become intoxicated. Reindeer are also associated with the shaman, and like Santa Claus, many people believed that the shaman could fly.[3]

Santa Claus rituals

Several rituals have developed around the Santa Claus figure that are normally performed by children hoping to receive gifts from him.

Christmas Eve rituals

In the United States, the tradition is to leave Santa a glass of milk and cookies; in Britain, he is sometimes given sherry and mince pies instead. Australians often leave Santa a beer and chips.

British , Australian and American children also leave out a carrot for Santa's reindeer, and were traditionally told that if they are not good all year round, that they will receive a lump of coal in their stockings, although this practice is now considered archaic. Children following the Dutch custom for sinterklaas will "put out their shoe" — that is, leave hay and a carrot for his horse in a shoe before going to bed — sometimes weeks before the sinterklaas avond. The next morning they will find the hay and carrot replaced by a gift; often, this is a marzipan figurine. Naughty children were once told that they would be left a roe (a bundle of sticks) instead of sweets, but this practice has been discontinued.

Letter writing

Writing letters to Santa Claus has been a Christmas tradition for children for many years. These letters normally contain a wishlist of toys and assertions of good behavior. Interestingly, some social scientists have found that boys and girls write different types of letters. Girls generally write more polite, longer (although they do not request more), and express more expressions of the nature of Christmas in their letters than in letters written by boys. Girls also request gifts for other people on a more frequent basis [Otnes, Kim, and Kim, 20-21].

Many postal services allow children to send letters to Santa Claus pleading their good behavior and requesting gifts; these letters may be answered by postal workers or other volunteers. Canada Post has a special postal code for letters to Santa Claus: H0H 0H0 (see: Ho ho ho), and since 1982 over 13,000 Canadian postal workers have volunteered to write responses.[4] Sometimes children's charities answer letters in poorer communities or from children's hospitals in order to give them presents that they would not otherwise receive.

Through the years Santa Claus of Finland has got over eight million letters. He gets over 600,000 letters every year from over 150 countries. Children from the Great Britain, Poland and Japan are the busiest writers. The Finnish Santa Claus lives in Korvatunturi but Santa's Official Post Office is situated in Rovaniemi at the Arctic circle. His address is this: Santa Claus, Santa Claus Village, FIN-96930 Arctic Circle, Finland.

Websites and e-mail

Some people have created websites designed to allow children and other interested parties "track" "Santa Claus" on Christmas Eve via radar, while in reality it is an US Air Force Jet which is supposed to come from an Air Force Base in Canada towards another base in Mexico City. In 1955, a Sears Roebuck store in Colorado Springs, Colorado, gave children a number to call a "Santa hotline". The number was mistyped and children called the Continental Air Defense Command (CONAD) on Christmas Eve instead. The Director of Operations, Harry Shoup, received the first call for Santa and realizing what this mistake was, told children that there were signs on the radar that Santa was indeed heading south from North Pole. In 1958, Canada and the United States jointly created the North American Air Defense Command (NORAD) and together tracked Santa Claus for children of North America that year and ever since.[5]. This tracking can now be done by children via the Internet and NORAD's website.

Many local television stations in the United States and Canada likewise track Santa Claus in their own metropolitan areas through the stations' meteorologists.

Many other websites are available year-round that are devoted to Santa Claus and keeping tabs on his activities in his workshop. Many of these websites also include e-mail addresses, a modern version of the postal service letter writing, in which children can send Santa Claus e-mail.

Songs

Over the years, Santa Claus has inspired several songs and even orchestral works. As early as 1853, Louis Antoine Jullien composed an orchestral piece titled Santa Claus which premiered to mixed reviews in New York that year [Horowitz, 213]. More popular, well-known songs about Santa Claus (mostly sung by children) include:

- "Here Comes Santa Claus" (1947) by Gene Autry and Oakley Haldeman

- "I Believe in Father Christmas" by Greg Lake and Peter Sinfield

- "Jolly Old St. Nicholas" traditional

- "Little Saint Nick" by Brian Wilson, performed by The Beach Boys

- "The Night Santa Went Crazy" (1996) by Weird Al Yankovic (satire)

- "Santa Baby" (1953) by Joan Javits, Philip Springer, and Tony Springer, performed by Eartha Kitt

- "Santa Claus is Coming to Town" (1935) by J. Fred Coots and Haven Gillespie

- "Up on the Housetop" traditional

"Santa Claus" in shopping malls

Santa Claus is also a costumed character who appears at Christmas time in department stores or shopping malls, or at parties. He is played by an actor, usually helped by other actors (often mall employees or contractors) dressed as elves or other creatures of folklore. His function is either to promote the store's image by distributing small gifts to children, or to provide a seasonal experience to children by having them sit on his knee (a practice now under review by some organisations in Britain [6], and Switzerland [7]), state what they wish to get, and often have a photograph taken. The area set up for this purpose is festively decorated, usually with a large throne, and is called variously "Santa's Grotto", "Santa's Workshop" or a similar term. In America the most notable of these is the Santa at the flagship Macy's store in New York City - he arrives at the store by sleigh in the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade on the last float, and his court takes over a large portion of one floor in the store. Essayist David Sedaris is known for the satirical diary he kept while working as an elf in the Macy's display, which he later published.

Quite often the Santa, if and when realised to be fake, says that he is not the real Santa and is helping him at this time of year. Most young children seem to understand this, as the "real" Santa would be extremely busy around Christmas.

Santa Claus on film

Probably the only other place where Santa Claus makes as many appearances as in the malls is on the big screen. Motion pictures of St. Nick abound and apparently constitute their own sub-genre of the Christmas film genre. Early films of Santa revolve around similar simple plots of Santa's Christmas eve visit to children. In 1897 a short film called Santa Claus Filling Stockings, Santa Claus is simply filling stockings from his pack of toys. Another film called Santa Claus and the Children was made in 1898. A year later, a film directed by George Albert Smith in 1899 titled Santa Claus (or The Visit from Santa Claus in the United Kingdom) was created. In this picture you see Santa Claus enter the room from the fireplace and proceed to trim the tree. He then fills the stockings that were previously hung on the mantle by the children. After walking backward and surveying his work, he suddenly darts at the fireplace and disappears up the chimney. Santa Claus' Visit in 1900 featured a scene with two little children kneeling at the feet of their mother and saying their prayers. The mother tucks the children snugly in bed and leaves the room. Santa Claus suddenly appears on the roof, just outside the children's bedroom window, and proceeds to enter the chimney, taking with him his bag of presents and a little hand sled for one of the children. He goes down the chimney and suddenly appears in the children's room through the fireplace. He distributes the presents and mysteriously causes the appearance of a Christmas tree laden with gifts. The scene closes with the children waking up and running to the fireplace just too late to catch him by the legs. A 1909 film by D. W. Griffith titled A Trap for Santa Claus shows children setting a trap to capture Santa Claus as he descends down the chimney, but instead capture their father who abandoned them and their mother but tries to burglarize the house after he discovers she inherited a fortune. A twenty-nine minute 1925 silent film production entitled Santa Claus by explorer/documentarian Frank E. Kleinschmidt filmed partly in northern Alaska and features Santa in his workshop, visiting his Eskimo neighbors, and tending his reindeer. A year later another movie titled Santa Claus was produced with sound on De Forest Phonofilm.[8] Over the years various actors have donned the red suit (aside from those discussed below), including Monty Woolley in Life Begins at Eight-thirty (1942), Alberto Rabagliati in The Christmas That Almost Wasn't (1966), Dan Aykroyd in Trading Places (1983), Jan Rubes in One Magic Christmas (1985), Jonathan Taylor Thomas in I'll Be Home for Christmas (1998), and Ed Asner in Elf (2003). Later films about Santa vary, but can be divided into the following themes.

Origins in film

Some films about Santa Claus seek to explore his origins. They explain how reindeer fly, where elves come from, and other questions children have generally asked about Santa. Two stop motion animation television specials addressed this issue: Santa Claus is Comin' to Town (1970) by Rankin/Bass with Mickey Rooney as the voice of Kris reveals how Santa delivered toys to children despite the fact that Burgermeister Meisterburger had forbidden children to play with them and The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus (1985), based on L. Frank Baum 's 1902 children's book of the same name, in which Santa is reared by mythical, magical creatures and is granted immortality by them. The feature film Santa Claus: The Movie (1985) starring David Huddleston as Santa Claus and British actress Judy Cornwell as his wife Anya shows how Santa and his wife are adopted by elves (including elves played by Dudley Moore and Burgess Meredith) in order to deliver their toys all over the world. Interestingly enough, none of these films focus on Santa Claus's saintly origins.

Questioning and believing

Another genre of Santa films seek to dispel doubts about his existence. One of the first films of this nature was titled A Little Girl Who Did Not Believe in Santa Claus (1907) and involves a well-to-do boy trying to convince his poorer friend that Santa Claus is real. She doubts because Santa has never visted her family because of their poverty. Miracle on 34th Street (1947) starring Natalie Wood as Susan Walker revolves around the disbelief of young Susan whose mother (Maureen O'Hara) employs a kind old man (Edmund Gwenn, who won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor) to play Santa Claus at Macy's; he later convinces Susan that he really is Santa. This film was remade in 1994 and stars Richard Attenborough as Kris Kringle and Mara Wilson as Susan Walker. The television special Yes Virginia There Is A Santa Claus (1991) follows the true story of a young girl, Virginia O'Hanlan, who writes a letter to the editor of the New York Sun in 1897 after her friends told her there was no Santa. The newspaper tells here there is a Santa, "He lives, and he lives forever." Francis Pharcellus Church was the real-life editor and is played by Charles Bronson in the film. The Polar Express (2004), based on the children's book of the same name, also deals with issues and questions of belief as a magical train conducted by Tom Hanks transports a doubting boy to the North Pole to visit Santa Claus.[9]

Santa as a hero

Some less-than-serious films feature Santa Claus as a superhero-type figure, such as the 1959 film titled Santa Claus produced in Mexico with José Elías Moreno as Santa Claus. In this movie Santa allies with Merlin the magician to battle the Devil who is attempting to trap Santa. In the Cold War-era film Santa Claus Conquers the Martians (1964) where Santa Claus is captured by Martians and brought to Mars and ultimately foils a plot to destroy him. The Night They Saved Christmas (1984) starring Art Carney as Santa likewise chronicles how Santa Claus and Claudia Baldwin (Jaclyn Smith), the wife of an oil explorer, have to save the North Pole from explosions while her husband is searching for oil in the Arctic. Santa Claus: The Movie also contains a subplot in which Santa Claus rescues Joe (Christian Fitzpatrick) from his best friend Cornelia's (Carrie Kei Heim]) evil uncle B. Z. (John Lithgow).[10] The latest film to depict Santa Claus in such a manner is The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (2005), in which Father Christmas (James Cosmo) supplies the Pevensie children with the weapons and tools they need to battle the White Witch (Tilda Swinton).

Succession of Santas

One genre of movies suggest that Santa Claus is not historically a single individual but a succession of individuals. In Ernest Saves Christmas (1988), Ernest (Jim Varney) aids Santa Claus/Seth Applegate (Douglas Seale) convince Joe Curruthers (Oliver Clark) to become the next Santa. In The Santa Clause (1994), Tim Allen plays Scott Calvin who accidentally causes Santa Claus to fall off the roof of his house. After he puts on Santa's robes, he becomes subject to the "Santa clause" in which he is required to become the next Santa. Reluctant at first, he falls in love with his newfound role. This film spawned a sequel in 2002, The Santa Clause 2 in which he must find a wife (the "Mrs. Clause"). A recent and unique television special also draws upon the succession theme. In Call Me Claus (2001) Lucy Cullins (Whoopi Goldberg) is an African American woman destined to become the next Santa Claus. She too is reluctant to take on the role.

Impostor Santas

Several films have been created which explore the consequences should an impostor Santa take over. Probably one of the first films featuring a fake Santa Claus is the 1914 silent film The Adventure of the Wrong Santa Claus written by Frederic Arnold Kummer. In this film a bogus Santa steals all the Christmas presents and amateur detective Octavius (played by Herbert Yost) tries to recover them. Arguably the most notorious impostor appears in the 1966 cartoon based on Dr. Seuss's children's book, How the Grinch Stole Christmas!, where the Grinch attempts to rob the Whos in Whoville of their Christmas, but has a change of heart. This animated feature was made into a movie with live actors in 2000 starring Jim Carrey as the Grinch and directed by Ron Howard.

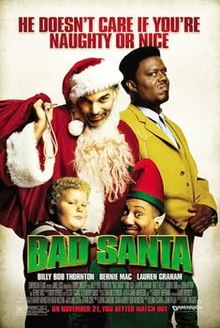

Another less-than-friendly impostor appears in A Christmas Story (1983) as a disgruntled mall Santa at Higbee's Department Store (a real store in downtown Cleveland, Ohio) in the fictional town of Holman, Indiana. Played by Jeff Gillen, Santa is depicted as a larger-than-life figure that terrifies rather than amuses children. Gillen's performance lends credence to the theory that the mall Santa is not quite genuine. Another recent devious mall Santa was played by Billy Bob Thornton in Bad Santa (2003), a film which gained normally family-friendly Disney "bad press".[11] Tim Burton's stop-action animated musical film The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) depicts Jack Skellington, the Pumpkin King of Halloween Town, wanting to become Santa Claus after an accidental visit to Christmas Town. After Halloween citizens capture Santa, they try to take over Christmas with disastrous results and Santa is almost eaten by the Boogeyman. Other darker impostors have appeared in such slasher films as the Silent Night, Deadly Night series of the 1980s, Santa Claws (1996), and in the short ". . . All Through the House," part of the Tales from the Crypt (1972) movie and later remade as episode 1.2 and directed by Robert Zemeckis for the HBO series of the same name. Both were inspired by the comic book.[12]

Christian opposition to Santa Claus

Despite Santa Claus's mixed Christian roots, he has become a secular representation of Christmas. As such, a small number of primarily fundamentalist Christian churches dislike the secular focus on Santa Claus and the materialist focus that present-giving gives to the holiday. Such a condemnation of Santa Claus is not a twentieth century phenomenon, but originated among some Protestant groups of the 16th century and was prevalent among the Puritans of 17th century England and America who banned the holiday as either pagan or Roman Catholic. Following the English Civil War, under Oliver Cromwell's government Christmas was banned. Following the Restoration of the monarchy and Puritans were out of power in England, the ban on Christmas was satirized in works such as Josiah King's The Examination and Tryal of Old Father Christmas; Together with his Clearing by the Jury (1686) [Nissenbaum, chap. 1].[13] Rev. Paul Nedergaard, a clergyman in Copenhagen, Denmark, drew the ire of Danish citizens in 1958 when he declared Santa to be a "pagan goblin" after Santa's image was used on fundraising materials for a Danish welfare organization [Clar, 337]. One prominent American denomination that refuses to celebrate Santa Claus or Christmas for similar reasons are the Jehovah's Witnesses, but some Christians of all stripes have oppositions to Santa Claus of some sort.[14] Some Christians would prefer that the focus be given on the actual birth of Jesus. Some parents are uncomfortable about "lying" to their children about the existence of Santa. Some parents worry that their children might think that if they were deceived by their parents about Santa Claus, they might be deceiving them about God's existence as well. While these viewpoints do not represent the majority of Christians, their comments have drawn the attention of critics such as the fictional Landover Baptist Church, whose website satirizes and parodies this viewpoint.[15]

Christmas gift-bringers around the world

See also: Christmas worldwide

Europe and North America

Throughout Europe and North America, Santa Claus is generally known as such, but in some countries the gift-giver's name, attributes, date of arrival, and even identity varies.

- Austria: Christkind ("Christ child")

- Belgium: Sinterklaas

- Bulgaria: Дядо Коледа (Diado Koleda (Grandfather Christmas)), used to be Дядо Мраз ( Diado Mraz (Grandfather Frost)) before 1989

- Canada: Santa Claus (among English speakers); Le Père Noël ("Father Christmas", among French speakers)

- Czech Republic: Svatý Mikuláš ("Saint Nicholas"); Ježíšek (diminutive form of Ježíš ("Jesus"))

- Denmark: Julemanden

- Estonia: Jõuluvana

- Finland: Joulupukki

- France: Le Père Noël ("Father Christmas"); Père Noël is also the common figure in other French-speaking areas)

- Germany: Weihnachtsmann ("Christmas Man"); Christkind in southern Germany

- Greece: Άγιος Βασίλης ("Saint Basil")

- Hungary: Mikulás ("Nicholas"); Jézuska or Kis Jézus ("child Jesus")

- Italy: Babbo Natale ("Father Christmas"); La Befana (similar role as Santa Claus; she rides a broomstick rather than a sleigh, although she is not normally considered a witch); Gesù Bambino ("Christ Child"); Santa Lucia (A child saint "operating" in the Northern regions, bringing gift on December the 12th. As well as the Befana, an old lady, comes out on the Epifany, Jan 6th)

- Liechtenstein: Christkind

- Netherlands & Flanders: Sinterklaas (not with Christmas but on December 5th)

- Norway: Julenissen

- Poland: Święty Mikołaj / Mikołaj ("Saint Nicholas"); Gwiazdor in some regions

- Portugal: Pai Natal ("[Father Christmas]]")

- Romania: Moş Crăciun ("Father Christmas"); Moş Niculae ("Father Nicholas")

- Russia: Дед Мороз (Ded Moroz, "Grandfather Frost)

- Spain: Los Reyes Magos ("The Three Kings"; "Magi"); the Tió de Nadal in Catalonia; Olentzero in the Basque Country.

- Sweden: Jultomten

- Switzerland: Christkind

- Turkey: Noel Baba

- United Kingdom: Father Christmas; Santa Claus

- United States: Santa Claus; Kris Kringle; Saint Nicholas or Saint Nick

Latin America

Santa Claus in Latin America is generally referred with different names from country to country.

- Argentina: Papá Noel

- Brazil: Papai Noel

- Costa Rica: San Nicolás or Santa Clos

- Chile: Viejito Pascuero

- Mexico: Santa Claus; Niño Dios ("child Jesus"); Los Reyes Magos

East Asia

People in East Asia, particularly countries that have adopted Western cultures, also celebrate Christmas and the gift-giver traditions passed down to them from the West.

- Japan: Santa Claus

- Taiwan: Santa Claus-derived (聖誕老人 or 聖誕老公公 "Old Man Christmas")

- The Philippines: Santa Claus

Africa and the Middle East

Christians in Africa and Middle East who celebrate Christmas generally ascribe to the gift-giver traditions passed down to them by Europeans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Descendants of colonizers still residing in these regions likewise continue the practices of their ancestors.[16]

- South Africa: Sinterklaas; Father Christmas; Santa Claus

References

- "Bad Disney". Washington Times. November 21, 2003.

- Barnard, Eunice Fuller. "Santa Claus Claimed as a Real New Yorker." New York Times. December, 19, 1926.

- Baum, L. Frank. The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus. 1902; reprint, New York: Penguin, 1986. ISBN 0451520645

- Belk, Russel W. "A Child's Christmas in America: Santa Claus as Deity, Consumption as Religion." Journal of American Culture, 10, no. 1 (Spring 1987), pp. 87-100.

- "Christmas Customs; Are They Christian?". The Watchtower (New York). December 15, 2000.

- Clar, Mimi. "Attack on Santa Claus." Western Folklore, 18, no. 4 (October 1959), p. 337.

- Clark, Cindy Dell. Flights of Fancy, Leaps of Faith: Children's Myths in Contemporary America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995. ISBN 0226107787

- "The Claus That Refreshes" at Snopes.com.

- "The Devil Is In Your Chimney!" at Landoverbaptist.org.

- Flynn, Tom. The Trouble with Christmas. Buffalo, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, 1993. ISBN 0879758481

- Horowitz, Joseph. Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall. New York: W. W. Norton, 2005. ISBN 0393057178

- "Is There a Santa Claus?" New York Sun. September 21, 1897.

- King, Josiah. The Examination and Tryal of Old Father Christmas; Together with his Clearing by the Jury . . . London: Charles Brome, 1686. Full text available here

- Lalumia, Christine. "The restrained restoration of Christmas". In the Ten Ages of Christmas at BBC.co.uk.

- [Moore, Clement Clarke]. "A Visit from St. Nicholas." Troy (N.Y.) Sentinel. December 23, 1823.

- Nissenbaum, Stephen. The Battle for Christmas. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1996. ISBN 0649412239

- Otnes, Cele, Kyungseung Kim, and Young Chan Kim. "Yes, Virginia, There is a Gender Difference: Analyzing Children's Requests to Santa Claus." Journal of Popular Culture, 28, no. 1 (Summer 1994), pp. 17-29.

- Ott, Jonathan. Pharmacotheon: Entheogenic Drugs, Their Plant Sources and History. Kennewick, Wash.: Natural Products Company, 1993. ISBN 0961423498

- Plath, David W. "The Japanese Popular Christmas: Coping with Modernity." American Journal of Folklore, 76, no. 302 (October-December 1963), pp. 309-317.

- Potter, Alicia. "Celluloid Santas" at Factmonster.com.

- Quinn, Seabury. Roads. 1948; facsimile reprint, Mohegan Lake, N.Y.: Red Jacket Press, 2005. ISBN 097488958X

- "St. Nicholas of Myra" in the Catholic Encyclopedia at NewAdvent.org.

- Sedaris, David. The Santaland Diaries and Seasons Greetings: Two Plays. New York: Dramatists Play Service, 1998. ISBN 0822216310

- Shenkman, Richard. Legends, Lies, and Cherished Myths of American History. New York: HarperCollins, 1988. ISBN 0060972610

- Siefker, Phyllis. Santa Claus, Last of the Wild Men: The Origins and Evolution of Saint Nicholas, Spanning 50,000 Years. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1996. ISBN 0786402466

- Twitchell, James B. Twenty Ads that Shook the World. New York: Crown Publishers, 2000. ISBN 0609605631

- "Why Track Him?" at NORADsanta.org.

See also

- Christmas

- Christmas Eve

- Companions of Saint Nicholas

- Father Christmas

- Christmas customs in Germany

- Ho ho ho

- Saint Nicholas of Myra

- Zwarte Piet

External links

- "Official" Santa Claus site: Santa Claus

- Christmas and Santa Claus by Santa Club

- The Original 1860s Thomas Nast Santa Claus Illustrations

- Jenny Nyström, the artist whose Christmas cards inspired Haddon Sundblom when he designed Coca-Cola's Santa.

- Snopes.com on the myth that Coca-Cola created the modern image of Santa Claus.

- Norman Rockwell's Santa and Expense Book

- SantaLand.com, one of the Internet's oldest Santa-related website, founded in 1991 by former Library of Congress archivist Jeff Guide

- NORAD Tracks Santa

- Santa Claus Plaza

- Santa Television, originating out of Rovaniemi in Finnish Lapland

- KringleQuest.com: The Unofficial Santa Claus: The Movie Website

- History of Santa Claus

- Santa Claus Pictures

- Santa Claus Vintage Postcards

- This American Life story about the history and stories of Santa Claus