Voynich manuscript

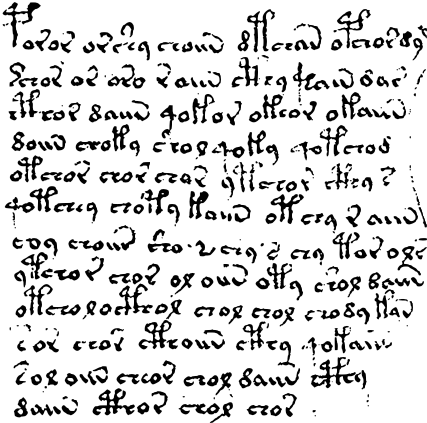

The Voynich Manuscript (VMs) is a mysterious illustrated book of unknown contents, written some 500 years ago by an anonymous author in an unidentified alphabet and unintelligible language.

Over its recorded existence, the VMs has been the object of intense study by many professional and amateur cryptographers, including some top American and British codebreakers of World War II fame—who all failed to decipher a single word. This string of egregious failures has turned the VMs into the Holy Grail of historical cryptology; but it has also given weight to the theory that the book is nothing but an elaborate hoax—a meaningless sequence of random symbols.

The book is named after the Russian-American book dealer Wilfrid M. Voynich, who acquired it in 1912. It is presently item MS 408 in the Beinecke Rare Book Library of Yale University.

Description

The book has about 240 vellum pages, and gaps in the page numbering (which apparently is later than the text) indicate that several pages were already missing by the time that Voynich acquired it. A quill pen was used for the text and figure outlines, and colored paint was applied (somewhat crudely) to the figures, possibly at a later date.

Illustrations

The illustrations of the manuscript shed little light on its contents, but imply that the book consists of half a dozen "sections", with different style and subject matter. Except for the last section, which contains only text, almost every page contains at least one illustration. The sections, and their conventional names, are:

- Herbal: each page displays one plant (sometimes two), and a few paragraphs of text—a format typical of European herbals of the time. Some parts of these drawings are larger and cleaner copies of sketches seen in the pharmaceutical section (below).

- Astronomical: contains circular diagrams, some of them with suns, moons, and stars, suggestive of astronomy or astrology. One series of 12 diagrams depicts conventional symbols for the zodiacal constellations (two fishes for Pisces, a bull for Taurus, a soldier with crossbow for Sagittarius, etc.). Each symbol is surrounded by exactly 30 miniature women figures, most of them naked, each holding a labeled star. The last two pages of this section (Aquarius and Capricorn, roughly January and February) were lost, while Aries and Taurus are split into four paired diagrams with 15 stars each. Some of these diagrams are on fold-out pages.

- Biological: a dense continuous text interspersed with figures, mostly showing small nude women bathing in pools or tubs connected by an elaborate network of pipes, some of them clearly shaped like body organs. Some of the women wear crowns.

- Cosmological: more circular diagrams, but of an obscure nature. This section too has fold-outs; one of them spans six pages and contains some sort of map or diagram, with nine "islands" connected by "causeways", castles, and possibly a volcano.

- Pharmaceutical: many labeled drawings of isolated part plants (roots, leaves, etc.); objects resembling apothecary jars drawn along the margins; and a few text paragraphs.

- Recipes: many short paragraphs, each marked with a flower-like (or star-like) "bullet".

The text

The text was clearly written from left to right, with a slightly ragged right margin. Longer sections are broken into paragraphs, sometimes with "bullets" on the left margin. There is no obvious punctuation. The ductus of the script flows smoothly, as if the scribe understood what he was writing when it was written; the manuscript does not give the impression that each character had to be calculated before being put on the page.

The text consists of over 170,000 discrete glyphs, usually separated from each other by thin gaps. Most of the glyphs are written with one or two simple pen strokes. While there is some dispute as to whether certain glyphs are distinct or not, an alphabet with 20-30 glyphs would account for virtually all of the text; the exceptions are a few dozen "weird" characters that occur only once or twice each.

Wider gaps divide the text into about 35,000 "words" of varying length. These seem to follow phonetic or orthographic laws of some sort; e.g. certain characters must appear in each word (like the vowels in English), some characters never follow others, some may be doubled but others can't.

Statistical analysis of the text reveals patterns similar to natural languages. For instance, the word frequencies follow Zipf's law, and the word entropy (about 10 bits per word) is similar to that of English or Latin texts. Some words occur only in certain sections, or in only a few pages; others occur throughout the manuscript. There are very few repetitions among the thousand or so "labels" attached to the illustrations. In the herbal section, the first word on each page occurs only on that page, and may be the name of the plant.

On the other hand, the VMs "language" is quite unlike European languages in several aspects. In particular, there are practically no words with more than 10 "letters". Also, the distribution of letters within the word is rather peculiar: some characters only occur at the beginning of a word, some only at the end, and some always in the middle section.

The text seems to be more repetitious than typical European languages; sequences where the same common word appears three times in a row occur (as if an English text contained the string and and and).

History

Since the VMs alphabet does not resemble any known script, and the text is still undeciphered, the only useful evidence as to the book's age and origin are the illustrations—especially the dresses and hairstyles of the human figures, and a couple of castles that are seen in the diagrams. They are all characteristically European, and based on that evidence most experts assign the book to dates between 1450 and 1520. This estimate is supported by other secondary clues.

The earliest confirmed owner of the manuscript was a certain Georg Baresch (Georgius Barschius in Latin), an obscure alchemist who lived in Prague in the early 17th century. Baresch apparently was just as puzzled as we are today about this "Sphynx" that had been "taking up space uselessly in his library" for many years. On learning that Athanasius Kircher, a Jesuit scholar from the Collegio Romano, had published a Coptic (Ethiopian) dictionary and "deciphered" the Egyptian hieroglyphs, he sent a sample copy of the VMs script to Kircher in Rome (twice), asking for clues. His 1639 letter to Kircher, which was recently located by René Zandbergen, is the earliest mention of the VMs that has been found so far.

It is not known whether Kircher answered the request, but apparently he was interested enough to try to acquire the book, which Baresch apparently refused to yield. Upon Baresch's death the manuscript passed to his friend Jan Marek Marci (Johannes Marcus Marci), then rector of Charles University in Prague; who promptly sent the book to Kircher, his longtime friend and correspondent. Marci's cover letter (1665) is still attached to the manuscript.

There are no records of the book for the next 200 years, but in all likelihood it was kept, with the rest of Kircher's correspondence, in the library of the Collegio Romano (now the Pontifical Gregorian University). There it probably sat until the troops of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy captured the city in 1870 and annexed the Papal States. The new Italian government decided to confiscate many properties of the Church, including the library of the Collegio. According to investigations by Xavier Ceccaldi and others, just before this happened many books of the University's library were hastily transferred to the personal libraries of its faculty, which were exempt from confiscation. Kircher's correspondence was among those books—and so apparently was the VMs, as it still bears the ex libris of Petrus Beckx, head of the Jesuit order and the University's Rector at the time. Beckx "private" library was moved to a Jesuit high school housed in Villa Mondragone, a large country palace near Rome (which, being owned by a local nobleman, was also exempt from confiscation).

Around 1912 the Collegio Romano was apparently short of money and decided to sell (very discreetly) some of its holdings. Wilfrid Voynich acquired 30 manuscripts, among then the VMs. In 1961, after Voynich's death, the book was sold by his widow to another antique book dealer H.P.Kraus. Unable to find a buyer, Kraus donated the VMs to Yale University in 1969.

Theories and speculation

Authorship

Many names have been proposed as possible authors of the VMs. Here are only the most popular ones.

- Roger Bacon. Marci's 1665 cover letter to Kircher says that, according to his late friend Raphael Mnishovsky, the book had been bought by Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, who believed its author to be Roger Bacon, a 13th century English polymath. Even though Marci said that he was "suspending his judgement" about this claim, it was taken quite seriously by Voynich, who did his best to confirm it. His conviction strongly influenced most decipherment attempts for the next 80 years. However, scholars who have looked at the VMs and are familiar with Bacon's works have flatly denied that possibility. One should note also that Raphael died in 1644, and the deal must have occurred before Rudolf's abdication in 1611—at least 55 years before Marci's letter.

- John Dee. The assumption that Roger Bacon was the author led Voynich to conclude that the person who sold the VMS to Rudolf could only be John Dee, a mathematician and astrologer at the court of Queen Elizabeth I, known to have owned a large collection of Bacon's manuscripts. Dee and his skryer (mediunic assistant) Edward Kelley lived in Bohemia for several years where they had hoped to sell their services to the Emperor. However, Dee's meticulously kept diaries do not mention that sale, and make it seem quite unlikely. Anyway, if the VMs author is not Bacon, the connection to Dee may just disappear. On the other hand, Dee himself may have written it and spread the rumour that it was originally a work of Bacon's in the hopes of later selling it.

- Edward Kelley, Dee's companion in Prague, was a self-styled alchemist who claimed to be able to turn copper into gold by means of a secret powder which he had dug out of a Bishop's tomb in Wales. As Dee's skryer, he claimed to be able to invoke angels through a crystal ball, and had long conversations with them—which Dee dutifully noted down. The angel's language was called Enochian, after Enoch, the Biblical father of Methuselah; according to legend, he had been taken on a tour of Heaven by angels, and later written a book about what he saw there. Several people (see below) have suggested that, just as Kelley invented Enochian to dupe Dee, he could have fabricated the VMs to swindle the Emperor (who was already paying Kelley for his supposed alchemical expertise). However, if Roger Bacon is not the VMS author, Kelley's connection to the VMs is just as vacuous as Dee's.

- Wilfrid Voynich was often suspected of having fabricated the VMs himself. As an antique book dealer, he probably had the necessary knowledge and means; and a "lost book" by Roger Bacon would have been worth a fortune. However, the recent discovery of Baresch's letter to Kircher has all but eliminated that possibility.

- Jacobus Sinapius. A photostatic reproduction of the first page of the VMs, taken by Voynich sometime before 1921, showed some faint writing that had been erased. With the help of chemicals, the text could be read as the name 'Jacobj à Tepenece': that would be Jakub Horcicky of Tepenec, in Latin Jacobus Sinapius—a specialist in herbal medicine who was the personal doctor of Rudolf II and curator of his botanical gardens. Voynich, and may other people after him, concluded from this "signature" that Jacobus owned the VMs before Baresch, and saw in that a confirmation of Raphael's story. Others have suggested that Jacobus himself could be the author.

- However, that writing has not yet been compared to Jacobus's signature; so it is still possible that it was written by a later owner or librarian, and is only this person's guess as to the book's author. (In the Jesuit history books that were available to Kircher, Jesuit-educated Jacobus is the only alchemist or doctor from Rudolph's court who deserves a full-page entry, while e.g. Tycho Brahe is barely mentioned.) Moreover, the chemicals applied by Voynich have so degraded the vellum that no trace of the signature can be seen today; thus there is also the suspicion that the signature was fabricated by Voynich in order to strengthen the Roger Bacon theory.

- Johannes Marci met Kircher when he led a delegation from Charles University to Rome in 1638; and over the next 27 years, the two scholars exchanged many letters on a variety of scientific subjects. Marci's trip was part of a continuing struggle by the secularist side of the University to maintain their independence from the Jesuits, who ran the rival Clementinum college in Prague. In spite those efforts, the two universities were merged in 1654, under Jesuit control. It has therefore been speculated that political animosity against the Jesuits led Marci to fabricate Baresch's letters, and later the VMs, in an attempt to expose and discredit their "star" Kircher.

- Marci's personality and knowledge appear to have been adequate for this task; and Kircher, a "Dr. Know-It-All" who is today remembered more by his egregious mistakes than by his genuine accomplishments, was an easy target. Indeed, Baresch's letter bears some resemblance to a hoax that orientalist Andreas Mueller once played on Kircher. It is worth noting that the only proofs of Georg Baresch's existence are three letters sent to Kircher: one by Baresch (1639), and two by Marci (about a year later). It is also curious that the correspondence between Marci and Kircher ends in 1665, precisely with the VMs "cover letter". However, Marci's secret grudge against the Jesuits is pure conjecture: a faithful Catholic, he himself had studied to become a Jesuit, and shortly before his death in 1667 he was granted honorary membership in their Order.

- Raphael Mnishovsky, the reputed source of Bacon's story, was himself a cryptographer (among many other things), and apparently invented a cipher which he claimed was uncrackable (ca. 1618). This has led to the theory that he produced the VMs as a practical demonstration of said cipher—and made poor Baresch his unwitting "guinea pig". After Kircher published his book on Coptic, Raphael (so the theory goes) may have thought that stumping him would be a much better trophy than stumping Baresch, and convinced the alchemist to ask the Jesuit's help. He would have invented the Roger Bacon story to motivate Baresch. Indeed, the disclaimer in the VMs cover letter could mean that Marci suspected a lie. However, there is no definite evidence for this theory.

Contents and purpose

The overall impression given by the surviving leaves of the manuscript suggests that it was meant to serve as a pharmacopoeia or to address topics in medieval or early modern medicine. However, the puzzling details of illustrations have fueled many theories about the book's origins, the contents of its text, and the purpose for which it was intended. Here are only a few of them:

- Herbal. The first section of the book is almost certainly an herbal, but attempts to identify the plants, either with actual specimens or with the stylized drawings of contemporary herbals, have largely failed. Only a couple of plants (including a wild pansy and the maidenhair fern) can be identified with some certainty. Those "herbal" pictures that match "pharmacological" sketches appear to be "clean copies" of these, except that missing parts were completed with improbable-looking details. In fact, many of the plants seem to be composite: the roots of one species have been fastened to the leaves of another, with flowers from a third.

- Sunflowers. Brumbaugh believed that one illustration depicted a New world sunflower, which would help date the manuscript and open up intriguing possibilities for its origin. However, the resemblance is slight, especially when compared to the original wild species; and, since the scale of the drawing is not known, the plant could be many other members of the same family—which includes the common daisy, chamomile, and many other species from all over the world.

- Alchemy. The basins and tubes in the "biological" section may seem to indicate a connection to alchemy, which would also be relevant if the book contained instructions on the preparation of medical compounds. However, alchemical books of the period share a common pictorial language, where processes and materials are represented by specific images (eagle, toad, man in tomb, couple in bed, etc.) or standard textual symbols (circle with cross, etc.); and none of these could be convincingly identified in the VMS.

- Alchemical herbal. Sergio Toresella, an expert on ancient herbals, pointed out that the VMs could be an alchemical herbal—which actually had nothing to do with alchemy, but was a bogus herbal with invented pictures, that a quack doctor would carry around just to impress his clients. Apparently there was a small cottage industry of such books somewhere in northern Italy, just at the right epoch. However, those books are quite different from the VMs in style and format; and they were all written in plain language.

- Astrological herbal. Astrological considerations frequently played a prominent role in herb gathering, blood-letting and other medical procedures common during the likeliest dates of the manuscript (see, for instance, Nicholas Culpeper's books). However, apart from the obvious Zodiac symbols, and one diagram possibly showing the Classical planets, no one has been able to interpret the illustrations within known astrological traditions (European or otherwise).

- Microscopes and telescopes. A circular drawing in the "astronomical" section depicts an irregularly shaped object with four curved arms, which some have interpreted as a picture of a galaxy, which could only be obtained with a telescope. Other drawings were interpreted as cells seen through a microscope. This would suggest an early modern, rather than a medieval, date for the manuscript's origin. However, the resemblance is rather questionable: on close inspection, the central part of the "galaxy" looks rather like a pool of water.

- Multiple authors. Prescott Currier, a US Navy cryptographer who worked the manuscript in the 1970s, observed that the pages of the "herbal" section could be separated into two sets, A and B, with distinctive statistical properties and apparently different handwritings. He concluded that the VMs was the work of two or more authors who used different dialects or spelling conventions, but who shared the same script. However, recent studies have questioned this conclusion. A handwriting expert who examined the book saw only one hand in the whole manuscript. Also, when all sections are examined, one sees a more gradual transition, with herbal A and herbal B at opposite ends. Thus, Prescott's observations could simply be the result of the herbal sections being written in two widely separated epochs.

The language

Many theories have been advanced as for the nature of the VMS "language". Here is a partial list:

- Letter-based cipher. According to this theory, the VMs contains a meaningful text in some European language, that was intentionally rendered obscure by mapping it to the VMs "alphabet" though a cipher of some sort—an algorithm that operated on individual letters.

- This has been the working hypothesis for most decipherment attempts in the 20th century, including an informal team of NSA cryptographers led by William F. Friedman in the early 1950s. Simple substitution ciphers can be excluded, because they are very easy to crack; so decipherment efforts have generally focused on polyalphabetic ciphers, invented by Alberti in the 1460s. This class includes the popular Vigenère cipher, which could have been strengthened by the use of nulls and/or equivalent symbols, letter rearrangement, false word breaks, etc. Some people assumed that vowels had been deleted before encryption. There have been several claims of decipherment along these lines, but none has been widely accepted — chiefly because the proposed decipherment algorithms depended on so many guesses by the user that they could extract a meaningful text from any random string of symbols.

- The main argument for this theory is that the use of a weird alphabet by a European author can hardly be explained except as an attempt to hide information. Indeed, Roger Bacon knew about ciphers, and the estimated date for the manuscript roughly coincides with the birth of cryptography as a systematic discipline. Against this theory is the observation that a polyalphabetic cipher would normally destroy the "natural" statistical features that are seen in the VMs, such as Zipf's law. Also, although polyalphabetic ciphers were invented about 1467, variants only became popular in the 16th century, somewhat too late for the estimated date of the VMs.

- Codebook cipher. According to this theory, the VMs "words" would be actually codes to be looked up in a dictionary or codebook. The main evidence for this theory is that the internal structure and length distribution of those words are similar to those of Roman numerals—which, at the time, would be a natural choice for the codes. However, book-based ciphers are viable only for short messages, because they are very cumbersome to write and to read.

- Steganography.This theory holds that the text of the VMs is mostly meaningless, but contains meaningful information hidden in inconspicuous details—e.g. the second letter of every word, or the number of letters in each line. This technique, called steganography, is very old, and was described e.g. by Johannes Trithemius in 1499. Some people suggested that the plain text was to be extraced by a grille of some sort. This theory is hard to prove or disprove, since stegotexts can be arbitrarily hard to crack. An argument against it is that using a cipher-looking cover text defeats the main purpose of steganography, which is to hide the very existence of the secret message.

- Some people have suggested that the meaningful text could be encoded in the length or shape of certain pen strokes. There are indeed examples of steganography from about that time that use letter shape (italic vs. upright) to hide information. However, when examined at high magnification, the VMs pen strokes seem quite natural, and substantially affected by the uneven surface of the vellum.

- Exotic natural language. The linguist Jacques Guy once suggested that the VMs text could be some exotic natural language, written in the plain with an invented alphabet. The word structure is indeed similar to that of many language families of East and Central asia, mainly Sino-Tibetan (Chinese "dialects", Tibetan, and Burmese), Austroasiatic (Vietnamese, Khmer, etc.) and possibly Tai (Thai, Lao, etc.). In many of these languages, the "words" (smallest language units with definite meaning) have only one syllable; and syllables have a rather rich structure, including tonal patterns.

- This theory has some historical plausibility. While those languages generally had native scripts, these were notoriously difficult for Western visitors; which motivated the invention of several phonetic scripts, mostly with Latin letters but sometimes with invented alphabets. Although the known examples are much later than the VMs, history records hundreds of explorers and missionaries who could have done it—even before Marco Polo's 13th century voyage, but especially after Vasco da Gama discovered the sea route to the Orient in 1499. The VMs author could also be a native from East Asia living in Europe, or educated at a European mission.

- The main argument for this theory is that it is consistent with all statistical properties of the VMs text which have been tested so far, including doubled and tripled words (which have been found to occur in Chinese and Vietnamese texts at roughly the same frequency as in the VMs.) It also explains the apparent lack of numerals and Western syntactic features (such as articles and copulas), and the general weirdness of the illustrations. Another possible hint are two large red symbols on the first page, which have been compared to a Chinese-style book title, upside down and badly copied. Also, the apparent division of the year into 360 degrees (rather than 365 days), in groups of 15 and starting with Pisces, are features of the Chinese agricultural calendar (jié qì). The main argument against the theory is the fact that no one (including scholars at the Academy of Sciences in Beijing) could find any clear examples of Asian symbolism or Asian science in the illustrations.

- Constructed language. The peculiar internal structure of VMs "words" has led several researchers to conjecture that the text could be a constructed language in the plain—specifically, a philosophical one. In languages of this class, the vocabulary is organized according to a category system, so that the general meaning of a word can be deduced from its sequence of letters. For example, in the modern constructed language Ro, bofo- is the category of colors, and any word beginning with those letters would name a color: so red is bofoc, and yellow is bofof. (This is an extreme version of the book classification scheme used by many libraries — in which, say, P stands for language and literature, PA for Greek and Latin, PC for Romance languages, etc..)

- This concept is quite old, as attested by John Wilkins's Philosophical Language (1668). In most known examples, categories are subdivided by adding suffixes; as a consequence, a text in a particular subject would have many words with similar prefixes — for example, all plant names would begin with the similar letters, and ditto for all diseases, etc.. This feature could then explain the repetitious nature of the Voynich text. However, no one has been able to assign a plausible meaning to any prefix or suffix in the VMs; and, moreover, known examples of philosophical languages are rather late (17th century).

- Random gibberish. The bizarre features of the VMs text (such as the doubled and tripled words) and the suspicious contents of its illustrations (such as the chimeric plants) have led many people to conclude that the manuscript may in fact be a hoax.

- In 2003, computer scientist Gordon Rugg showed that text with characteristics similar to the VMs could have been produced using a table of word prefixes, stems, and suffixes, which would have been selected and combined by means of a perforated paper overlay. The latter device, known as a Cardan grille, was invented around 1550 as an encryption tool, and was apparently used by Edward Kelley to fabricate his Enochian "language". However, the pseudo-texts generated in Gordon Rugg's experiments do not have the same words and frequencies as the VMs; its resemblance to "Voynichese" is only visual, not quantitative. Since one can produce random gibberish that resembles English (or any other language) to a similar extent, these experiments are not yet convincing.

VMs influence on popular culture

A number of items in popular culture appear to have been influenced, at least in part, by the Voynich Manuscript. While the dangerous grimoire called the Necronomicon, appearing in the fantasy Cthulhu Mythos, was likely created by H. P. Lovecraft without knowledge of the Voynich Manuscript, since the publication in 1969 of Colin Wilson's short story "The Return of the Lloigor", wherein a character discovers that the Voynich Manuscript is an incomplete copy of the grimoire, the fictional Necronomicon has since been repeatedly identified with this real mystery by other authors.

Drawings and script reminiscent of the VMs were incorporated into the plot of the motion picture Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

Links and references

Books

- M. E. D'Imperio, The Voynich manuscript an elegant enigma. National Security Agency/Central Security Service (1978).

- Robert S. Brumbaugh, The most mysterious manuscript : the Voynich 'Roger Bacon' cipher manuscript (1978).

- Leo Levitov, Solution of the Voynich Manuscript (1987)

- John Stojko, Letters to God's eye

- Mario M. Perez-Ruiz, El Manuscrito Voynich (2003)

External links

- A site on the Voynich Manuscript

- Voynich Manuscript web directory at Google

- Homepage for the European Voynich Manuscript Transcription Project

- Nature news article: World's most mysterious book may be a hoax

- Bibliography of Voynich manuscript related works

- http://rec-puzzles.org/sol.pl/cryptology/Voynich

- http://www.keele.ac.uk/depts/cs/staff/g.rugg/voynich/