Catholic Church

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

|

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church.[note 1] is the world's largest Christian church, with more than a billion members. A communion of the Western (Latin Rite) church and 22 autonomous Eastern Catholic churches (called particular churches) comprising a total of 2,795 dioceses in 2008, the Church's highest earthly authority in matters of faith, morality, and governance is the Pope,[12] currently Pope Benedict XVI, who holds supreme authority in concert with the College of Bishops of which he is the head.[13][14][15] The Catholic community is made up of an ordained ministry and the laity; members of either group may belong to organized religious communities.[16] The Church defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity.[17] It operates social programs and institutions throughout the world, including Catholic schools, universities, hospitals, missions and shelters, and the charity confederation Caritas Internationalis.

The Catholic Church believes itself to be the original Church founded by Jesus upon the Apostles,[18] among whom Simon Peter held the position of chief apostle.[19] The Church also believes that its bishops, through apostolic succession, are consecrated successors of these apostles,[20][21] and that the Bishop of Rome (the Pope) as the successor of Peter, possesses a universal primacy of jurisdiction and pastoral care.[22] Church doctrines have been defined through various ecumenical councils, following the example set by the first Apostles in the Council of Jerusalem.[23] On the basis of promises made by Jesus to his apostles, described in the Gospels, the Church believes that it is guided by the Holy Spirit and so protected from falling into doctrinal error.[24][25][26] Catholic beliefs are based on the deposit of Faith (containing both the Holy Bible and Sacred Tradition) handed down from the time of the Apostles, which are interpreted by the Church's teaching authority. Those beliefs are summarized in the Nicene Creed and formally detailed in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.[27] Formal Catholic worship is termed the liturgy. The Eucharist is the central component of Catholic worship. It is one of seven sacraments that mark key stages in the lives of believers.

With a history spanning almost two thousand years, the Church is "the world's oldest and largest institution"[28] and has played a prominent role in the history of Western civilization since at least the 4th century.[29] In the 11th century, a major split, sometimes called the Great Schism, occurred between Eastern and Western Christianity. Those Eastern churches that remained in or re-established communion with the Pope now form the Eastern Catholic churches. Those that remain independent of papal authority are usually known as Orthodox churches. In the 16th century, partly in response to the rise of the Protestant Reformation, the Church engaged in its own process of reform and renewal, known as the Counter-Reformation.

Although the Church maintains that it is the "One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church" founded by Jesus and in which is found the fullness of the means of salvation,[30][31] it also acknowledges that the Holy Spirit can make use of other Christian communities to bring people to salvation.[32][33] It believes that it is called by the Holy Spirit to work for unity among all Christians, a movement known as ecumenism.[33]

Origin and mission

Origin

According to its doctrine, the Catholic Church is the original Christian church founded by Jesus Christ.[34][35][36] The New Testament records the activities and teaching of his group of sectarian Jews and his appointing of the twelve Apostles, and his giving them authority to continue his work.[34] Catholics believe that Jesus designated Simon Peter as the leader of the apostles by proclaiming "upon this rock I will build my church ... I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven ... ".[25][35][37][38][39] Catholics believe that the coming of the Holy Spirit upon the apostles, in an event known as Pentecost, signaled the beginning of the public ministry of the Church. All duly consecrated bishops since then are considered the successors to the apostles.[35][39]

The traditional narrative places Peter in Rome, where he founded a church and served as the first bishop of the See of Rome, later consecrating Linus as his successor, thus beginning the line of Popes.[40][41] Elements of this traditional narrative agree with the surviving historical evidence which includes the writings of Saint Paul, several early Church Fathers (among them Pope Clement I)[42] and some archaeological evidence.[40] Although in the past some Biblical scholars thought the word 'rock' referred to Jesus or to Peter’s faith, the majority now understand it as referring to the person of Peter.[43] Some historians of Christianity assert that the Catholic Church can be traced to Jesus's consecration of Peter,[41][44] some that Jesus did not found a church in his lifetime but provided a framework of beliefs,[45] while others do not make a judgement about whether or not the Church was founded by Jesus but disagree with the traditional view that the papacy originated with Peter. These assert that Rome may not have had a bishop until after the apostolic age and suggest the papal office may have been superimposed by the traditional narrative upon the primitive church[46][47] although some of these assert that the papal office had indeed emerged by the mid 150s.[48][49]

Mission and purpose

The Church believes that its mission is founded upon Jesus' command to his followers to spread the faith across the world:[50] "Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you".[51][52][53] Pope Benedict XVI summarized this mission as a threefold responsibility to proclaim the word of God, celebrate the sacraments, and exercise the ministry of charity.[54] As part of its ministry of charity, the Church runs worldwide agencies such as Caritas Internationalis, whose national subsidiaries include CAFOD and Catholic Relief Services. Other institutions include Catholic schools, Catholic universities, Catholic Charities, the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul, Marriage Encounter, hospitals, orphanages, nursing homes, homeless shelters, as well as ministries to the poor, families, the elderly, AIDS victims, and pregnant and abused women.[55]

Beliefs

The Catholic Church holds that there is one eternal God, who exists as a mutual indwelling of three persons: God the Father; God the Son; and the Holy Spirit. Catholic beliefs are summarized in the Nicene Creed[56] and detailed in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.[27][57] The Nicene Creed also forms the central statement of belief of other Christian denominations.[58] Chief among these are Eastern Orthodox Christians, whose beliefs are similar to those of Catholics, differing mainly with regard to papal infallibility, the filioque clause and the Immaculate Conception of Mary.[59][60] The various Protestant denominations vary in their beliefs, but generally differ from Catholics regarding the Pope, Church tradition, the Eucharist, veneration of saints, and issues pertaining to grace, good works and salvation.[61]

Catholic belief holds that the Church "... is the continuing presence of Jesus on earth."[62] To Catholics, the term "Church" refers to the people of God, who abide in Jesus and who, "... nourished with the Body of Christ, become the Body of Christ."[63] The Church teaches that the fullness of the "means of salvation" exists only in the Catholic Church but acknowledges that the Holy Spirit can make use of Christian communities separated from itself to bring people to salvation. It teaches that anyone who is saved is saved indirectly through the Church if the person has invincible ignorance of the Catholic Church and its teachings (as a result of parentage or culture, for example), yet follows the morals God has dictated in his heart and would, therefore, join the Church if he understood its necessity.[64][65] It teaches that Catholics are called by the Holy Spirit to work for unity among all Christians.[64][65]

The Council of Jerusalem, convened by the Apostles around the year 50 to clarify Church teachings, set the precedent for later councils of the Church, convened by Church leaders throughout history.[23][66][67] The most recent Church council was the Second Vatican Council, which closed in 1965.[68]

Teaching authority, seven sacraments

Based on the promises of Jesus in the Gospels, the Church believes that it is continually guided by the Holy Spirit and so protected infallibly from falling into doctrinal error.[13][69] The Catholic Church teaches that the Holy Spirit reveals God's truth through Sacred Scripture, Sacred Tradition and the Magisterium.[70]

Sacred Scripture consists of the 73 book Catholic Bible. This is made up of the 46 books found in the ancient Greek version of the Old Testament—known as the Septuagint[71]—and the 27 New Testament writings first found in the Codex Vaticanus Graecus 1209 and listed in Athanasius' Thirty-Ninth Festal Letter.[72] [note 2] Sacred Tradition consists of those teachings believed by the Church to have been handed down since the time of the Apostles.[69] Sacred Scripture and Sacred Tradition are collectively known as the "deposit of faith" (depositum fidei). These are in turn interpreted by the Magisterium (from magister, Latin for "teacher"), the Church's teaching authority, which is exercised by the pope and the college of bishops in union with the pope.[73]

According to the Council of Trent, Jesus instituted seven sacraments and entrusted them to the Church.[74] These are Baptism, Confirmation, the Eucharist, Reconciliation (Penance), Anointing of the Sick (formerly Extreme Unction or the "Last Rites"), Holy Orders and Holy Matrimony. Sacraments are important visible rituals which Catholics see as signs of God's presence and effective channels of God's grace to all those who receive them with the proper disposition (ex opere operato).[75][76] With the exception of baptism, the sacraments are administered by ordained members of the Catholic clergy. Baptism is the only sacrament that may be administered in emergencies by any Catholic, or even a non-Christian who "has the intention of baptizing according to the belief of the Catholic Church".[77]

God the Father, creation, and original sin

The Church teaches that God is the source and creator of all that exists,[78] and that he is a loving entity who is directly involved in the world and in people's lives,[79] desiring his creatures to love him and to love each other.[80][81] Catholicism teaches that while human beings live in a visible, material world, their souls occupy an invisible, spiritual world, in which spiritual beings called angels exist to "worship and serve God".[82] When some angels chose to rebel against God, they became demons, antagonistic both to God and to mankind.[83] The leader of this rebellion, "Lucifer", has also been called "Satan" and the devil.[84]

Satan is believed to have tempted the first humans, Adam and Eve, whose subsequent act of original sin brought suffering and death into the world.[85] This event, known in Catholic belief as the Fall of Man, separated humanity from its original intimacy with God. The Catechism states that the description of the fall, in Genesis 3, uses figurative language, but affirms that "... a deed that took place at the beginning of the history of man" that resulted in "a deprivation of original holiness and justice" that makes each person "subject to ignorance, suffering, and the dominion of death: and inclined to sin". Catholic doctrine accepts the possibility that God's creation occurred in a way consistent with evolution but rejects as outside the scope of science any efforts to use of the theory to deny supernatural divine creation.[86] The soul did not evolve, according to Catholic doctrine, but was infused into man and woman directly by God.[85]

The Church teaches that original sin and all personal sins can be cleansed through the sacrament of Baptism.[87] This sacramental act admits a person as a full member of the natural and supernatural Church and can only be conferred on a person once.[87]

Jesus, sin and Penance

Catholics believe that Jesus is the Messiah of the Old Testament's Messianic prophecies.[88] The Nicene Creed states that he is "... the only begotten son of God, ... one in being with the Father. Through him all things were made". In an event known as the Incarnation, the Church teaches that, through the power of the Holy Spirit, God became united with human nature when Jesus was conceived in the womb of the Virgin Mary. Jesus is believed, therefore, to be both fully divine and fully human. It is taught that Jesus' mission on earth included giving people his teachings and providing his example for them to follow, as recorded in the four Gospels.[89]

Falling into sin is considered the opposite to following Jesus, weakening a person's resemblance to God and turning their soul away from his love.[90] Sins range from the less serious venial sins to more serious mortal sins which end a person's relationship with God.[90][91] The Church teaches that through the passion (suffering) of Jesus and his crucifixion, all people have an opportunity for forgiveness and freedom from sin, and so can be reconciled to God.[88][92] The Resurrection of Jesus, according to Catholic belief, gained for humans a possible spiritual immortality previously denied to us because of original sin.[93] By reconciling with God and following Jesus' words and deeds, the Church believes one can enter the Kingdom of God, which is the "... reign of God over people's hearts and lives."[94][95]

After baptism, the sacrament of Reconciliation (Penance or Confession) is the means by which Catholics believe they can obtain forgiveness for subsequent sin and receive God's grace. Catholics believe Jesus gave the apostles authority to forgive sins in God's name.[96] After making an examination of conscience that often involves a review of the ten commandments, the sacrament involves confession of sins by an individual to a priest, who then offers advice and imposes a particular penance to be performed. The penitent then prays an act of contrition and the priest administers absolution, formally forgiving the person of his sins.[97] The priest is forbidden—under penalty of excommunication—to reveal any sin or disclosure heard under the seal of confession. Penance helps prepare Catholics before they can licitly receive the sacraments of Confirmation and the Eucharist.[98][99] The Code of Canon Law requires all Catholics to confess mortal sins at least once a year,[100] although frequent reception of the sacrament is recommended. This is commonly known as the second precept of the Church.[101] There is evidence from the UK[102] and USA[103] that at least three-quarters of professed Catholics do not adhere to this requirement of canon law.

Holy Spirit and Confirmation

Jesus told his apostles that—after his death and resurrection—he would send them the "Advocate", the "Holy Spirit", who "... will teach you all things".[104][105] Through the sacrament of Confirmation, Catholics believe they receive the Holy Spirit. Since the Holy Spirit is a Person of the Trinity, the Church teaches that receiving the Holy Spirit is an act of receiving God.[106] Confirmation, sometimes called the "sacrament of Christian maturity", is believed to increase and deepen the grace received at Baptism,[107] as the confirmand is sealed with the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit, i.e., wisdom (to see and follow God's plan), understanding, counsel (right judgement), fortitude (courage), knowledge, piety (reverence), and fear of the Lord (rejoicing in the presence of God; a spirit of holy fear in God's presence).[108][109] The corresponding fruits of the Holy Spirit are charity (love), joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, generosity, gentleness, faithfulness, modesty, self-control, and chastity.[108][109] To be properly confirmed, Catholics must be in a state of grace, which means they cannot be conscious of having committed an unconfessed mortal sin.[109] They must also have prepared spiritually for the sacrament, chosen a sponsor for spiritual support, and selected a saint to be their special patron and intercessor.[107] In the Eastern Catholic Churches, baptism, including infant baptism, is immediately followed by Confirmation – referred to as Chrismation[110] – and the reception of the Eucharist.[109][111]

Final judgment and afterlife

Belief in an afterlife is part of Catholic doctrine, the "four last things" being death, judgment, heaven, and hell. The Church teaches that immediately after death the soul of each person will receive a particular judgment from God, based on the deeds of that individual's earthly life.[109][112] This teaching also attests to another day when Jesus will sit in a universal judgment of all mankind.[55][113] This final judgment, according to Church teaching, will bring an end to human history and mark the beginning of a new and better heaven and earth ruled by God in righteousness.[109][114] The basis upon which each person's soul will be judged is detailed in the Gospel of Matthew which lists works of mercy to be performed even to people considered "the least".[113][114] Emphasis is upon Jesus' words that "Not everyone who says to me, 'Lord, Lord,' shall enter the kingdom of heaven, but he who does the will of my Father who is in heaven".[114] According to the Catechism, "The Last Judgement will reveal even to its furthest consequences the good each person has done or failed to do during his earthly life."[114]

There are three states of afterlife in Catholic belief. Heaven is a time of glorious union with God and a life of unspeakable joy that lasts forever.[109][112] Purgatory is a temporary condition for the purification of souls who, although saved, are not free enough from sin to enter directly into heaven. It is a state requiring penance and purgation of sin through God's mercy aided by the prayers of others.[109][112] Finally, those who chose to live a sinful and selfish life, did not repent, and fully intended to persist in their ways are sent to hell, an everlasting separation from God.[109][115] The Church teaches that no one is condemned to hell without having freely decided to reject God and his love.[109][112] He predestines no one to hell and no one can determine whether anyone else has been condemned.[109][112] Catholicism teaches that through God's mercy a person can repent at any point before death and be saved "like the good thief who was crucified next to Jesus".[112][116]

Social teaching

In addition to operating numerous social ministries throughout the world, the Church teaches that individual Catholics are required to practice the spiritual and corporal works of mercy as well. The seven corporal works of mercy are: feeding the hungry, giving drink to the thirsty, sheltering the homeless, clothing the naked, visiting the sick, visiting the imprisoned, and burying the dead.[109] Welcoming strangers, immigrants, and refugees could be said to be another corporal work of mercy. The spiritual works of mercy include: instructing, advising, consoling, comforting, forgiving, bearing wrongs patiently, and praying for the living and the dead.[55][109] In conjunction with the work of mercy to visit the sick, the Church offers the sacrament of Anointing of the Sick,[109] administered only by a priest.[117] Church teaching on works of mercy and the new social problems of the industrial era led to the development of Catholic social teaching, which emphasizes human dignity and commits Catholics to the welfare of others.[55][109]

Prayer and worship

Catholic liturgy is regulated by Church authority[118] and consists of the Eucharist and Mass, the other sacraments, and the Liturgy of the Hours. According to the precepts of the Church, every Catholic is required to attend Mass on Sundays and holy days of obligation[109] and confess mortal sins at least once a year.[119] They should also receive the Eucharist at least once during Easter season, observe the prescribed days of fasting and of abstinence as established by the Church, and help provide for the Church's needs.[120] (For the Latin Church, the holy days of obligation are set forth in the Code of Canon Law, but they vary from nation to nation, as requested by each nation's conference of bishops and approved by the Holy See.) All Catholics are expected to participate in the liturgical life of the Church, but individual or communal prayer and devotions—while encouraged—are a matter of personal preference.[121]

In addition to the Mass, the Catholic Church considers prayer to be one of the most important elements of Christian life. The Catechism identifies three types of prayer: vocal prayer (sung or spoken), meditation, and contemplative prayer. Two of the most common devotional prayers of the Catholic Church are the Rosary and Stations of the Cross.[122] These prayers are most often vocal, yet also meditative and contemplative. Benediction and Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament are common forms of contemplative prayers.[123]

Diverse traditions of worship

Differing liturgical traditions, or rites, exist throughout the universal Church, reflecting historical and cultural diversity rather than differences in beliefs.[124] The most commonly used liturgy is the Roman Rite (which is used in most of the Latin Catholic Church, but not in the Eastern Catholic Churches nor in those parts of the Latin Church where other Latin liturgical rites are in use). Presently, the Roman Rite exists in two authorized forms: the ordinary form (the 1969 Mass of Paul VI, celebrated mostly in the vernacular, i.e., the language of the people) and the extraordinary form (the 1962 edition of the Tridentine or Latin Mass ).[125][126][note 3] In the United States, certain "Anglican Use" parishes use a variation of the Roman rite which retains many aspects of the Anglican liturgical rites.[note 4] Other Western rites (non-Roman) include the Ambrosian Rite and the Mozarabic Rite.

The Eastern Catholic Churches refer to the Eucharistic celebration as the Divine Liturgy. The Eastern Catholic Churches use one of the following rites: the Byzantine rite, Alexandrian or Coptic rite, Syriac rite, Armenian rite, Maronite rite, and Chaldean rite. The Latin Catholic Church and the various Eastern Catholic Churches each follow a liturgical year—an annual calendar—which sets aside certain days and seasons to celebrate key events in the life of Jesus.[128] Advent, Christmas and the Epiphany celebrate his expected coming, birth and manifestation. Lent is the period of purification and penance that ends during Holy Week with the Easter Triduum. These days recall Jesus' last supper with his disciples, death on the cross, burial and resurrection. The feast of the Ascension of Jesus is followed by Pentecost which recalls the account of the descent of the Holy Spirit upon Jesus' disciples.[128]

Eucharist

.

The Eucharist is celebrated at each Mass and is the center of Catholic worship.[129][130] The Words of Institution for this sacrament are drawn from the Gospels and a Pauline letter.[131] In its main elements and prayers, the Catholic Mass celebrated today, according to professor Alan Schreck, is "almost identical" to the form described in the Didache and First Apology of Justin Martyr in the late 1st and early 2nd centuries.[132][133] At each Mass, Catholics believe that the bread and wine become supernaturally transubstantiated into the true Body and Blood of Christ. The Church teaches that Jesus established a New Covenant with humanity through the institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper. Because the Church teaches that Christ is present in the Eucharist,[125] there are strict rules about its celebration and reception. The ingredients of the bread and wine used in the Mass are specified and Catholics must abstain from eating for one hour before receiving Communion.[134] Those who are conscious of being in a state of mortal sin are forbidden from this sacrament unless they have received absolution through the sacrament of Reconciliation (Penance).[134] Catholics are not permitted to receive communion in Protestant churches because of their different beliefs and practices regarding Holy Orders and the Eucharist.[135]

Mary and the saints

Prayers to, devotions to, and veneration of the Virgin Mary and the saints are a common part of Catholic life but are distinct from the worship of God.[136] Catholic teaching maintains that the Church exists simultaneously on earth (Church militant), in purgatory (Church suffering), and in heaven (Church triumphant); thus Mary and all other saints are alive and part of the living Church.[137] This unity of the Church in heaven, in purgatory, and on earth is the "Communion of Saints".[137][138] Explaining the intercession of saints, the Catechism states that the saints "... do not cease to intercede with the Father for us ... so by their fraternal concern is our weakness greatly helped."[136][138]

The Church holds Mary, as ever Virgin and Mother of God, in special regard. She is believed to have been conceived without original sin, and to have been assumed into heaven. These teachings, the focus of Roman Catholic Mariology, are considered infallible. Several liturgical Marian feasts are celebrated throughout the Church Year and she is honored with many titles such as Queen of Heaven (in Latin, Regina Coeli). Pope Paul VI called her Mother of the Church (in Latin, Mater Ecclesiae), because by giving birth to Christ, she is considered to be the spiritual mother to each member of the Body of Christ.[139] Because of her influential role in the life of Jesus, prayers and devotions, such as the Rosary, the Hail Mary, the Salve Regina and the Memorare are common Catholic practices.[122] The Church has affirmed the validity of Marian apparitions (supernatural experiences of Mary by one or more persons) such as those at Lourdes, Fatima and Guadalupe[140] while others such as Međugorje are still under investigation.

Pilgrimage has been an important element of Catholic spirituality since at least the second century. Devotional journeys to the sites of biblical events or to places connected with Jesus, Mary or the saints are considered an aid to spiritual growth and are popular Catholic devotions.[141] Western Europe has more than 6,000 pilgrimage destinations that generate around 60 million faith-related visits a year.[142]

Church organization and community

While the Church considers Jesus to be its ultimate head, the spiritual leader and head of the Church organization is the pope.[143][note 5] The pope governs from the Vatican City in Rome – a sovereign nation of which he is the head of state.[145] Each pope is elected for life by the College of Cardinals, a body composed of clerics (normally bishops) who have been elevated to the rank of cardinal. The cardinals, who also serve as papal advisors, may select any Catholic male as pope, but if the candidate is not already a bishop, he must become one before taking office.[146]

The pope is assisted in the Church's administration by the Roman Curia, or civil service. The Church is governed according to formal regulations set out in the Code of Canon Law. The official language of the Church is Latin, although Italian is the working language of the Vatican administration.[147] As of 2008, the worldwide Catholic Church comprises 2,795 dioceses (also called sees or, in the East, eparchies), grouped into 23 particular Churches – the Latin-rite Church and 22 Eastern Catholic Churches – each with distinct traditions regarding the liturgy and the administration of the sacraments.[148] Each diocese is divided into individual communities called parishes, each staffed by one or more priests.[149] The church community is made up of ordained members (such as bishops, priests and deacons,) and the laity. Members of religious orders such as nuns, friars and monks are lay members unless individually ordained as priests.[150]

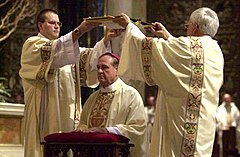

Ordained members and Holy Orders

Men may become ordained clergy to serve as deacons, priests or as bishops through the sacrament of Holy Orders which is conferred by one or more bishops through the laying on of hands.[151] Deacons and all other clergy may preach, teach, baptize, witness marriages and conduct funeral liturgies.[152] The sacraments of the Eucharist, Reconciliation (Penance) and Anointing of the Sick may only be administered by priests or bishops. All clergy who are bishops [note 6] form the College of Bishops and are jointly considered the successors of the apostles.[153][154] Only bishops can administer the sacrament of Holy Orders.[151] They are also responsible for teaching, governing, and sanctifying the faithful of their diocese, sharing these duties with the priests and deacons who serve under them.

The Church teaches that since the twelve apostles chosen by Jesus were all male, only men may be ordained as priests.[155] While some consider this to be evidence of a discriminatory attitude toward women,[156] the Church believes that Jesus called women to different yet equally important vocations in Church ministry.[157] Pope John Paul II, in his apostolic letter Christifideles Laici, states that women have specific vocations reserved only for the female sex, and are equally called to be disciples of Jesus.[158]

Married men may become deacons but only celibate men are ordinarily ordained as priests in the Latin Rite.[159][160] However, married clergymen who have been received into the Church from other denominations may be exempted from this rule.[161] The Eastern Catholic Churches ordain both celibate and married men to the priesthood, but married men cannot become bishops.[162][163] All 23 particular Churches of the Catholic Church maintain the ancient tradition that marriage is not allowed after ordination. Men with transitory homosexual leanings may be ordained deacons following three years of prayer and chastity, but homosexual men who are sexually active, or those who have deeply rooted homosexual tendencies, cannot be ordained.[164] [note 7]

Lay members, marriage

The laity consists of those Catholics who are not ordained clergy. Saint Paul compared the diversity of roles in the Church to the different parts of a body, all being important to enable the body to function.[16] The Church therefore considers that lay members are equally called to live according to Christian principles, to work to spread the message of Jesus, and to effect change in the world for the good of others. The Church calls these actions participation in Christ's priestly, prophetic and royal offices.[168] Marriage and the consecrated life are lay vocations. The sacrament of Holy Matrimony in the Latin rite is not administered (conferred) by the priest or deacon who presides. Instead, the ministers of the sacrament are the bride and groom, who mutually confer the sacrament upon each other by expressing their consent before the priest or deacon who serves as a witness. In the Eastern Catholic Churches the minister of this sacrament, which is called "Crowning", is the priest or bishop who, after receiving the mutual consent of the spouses, successively crowns the bridegroom and the bride as a sign of the marriage covenant.[169] Church law makes no provision for divorce, but annulment may be granted when proof is produced that essential conditions for contracting a sacramental union (valid marriage) were absent. Since the Church condemns all forms of artificial birth control, married persons are expected to be open to new life in their sexual relations.[170] Natural family planning is approved.[171]

Lay ecclesial movements consist of lay Catholics organized for purposes of teaching the faith, cultural work, mutual support or missionary work.[172] Such groups include: Communion and Liberation, Opus Dei and many others.[172] Some non-ordained Catholics practice formal, public ministries within the Church.[173] These are called lay ecclesial ministers, a broad category which may include pastoral life coordinators, pastoral assistants, youth ministers and campus ministers.[174]

Consecrated life

Both the ordained and the laity may enter the cloistered consecrated life as monks or nuns. There are also friars and sisters who engage in teaching and missionary activity and charity work such as the various mendicant orders. A candidate takes vows confirming their desire to follow the three evangelical counsels of chastity, poverty and obedience.[175] The majority of those wishing to enter the consecrated life join one of the religious institutes which are also referred to as monastic or religious orders. They follow a common rule such as the Rule of St Benedict and agree to live under the leadership of a superior.[176][177] They usually live together in a community but individuals may be given permission to live as hermits, or to reside elsewhere, for example as a serving priest or chaplain.[178] Examples of religious institutes include the Benedictines, Carmelites, Cistercians, Augustinians, Dominicans, Franciscans, Marist Brothers, Paulist Fathers, Sisters of Charity, Sisters of the Destitute, Sisters of Mercy, Legionaries of Christ and the Society of Jesus (Jesuits), but there are many others.[175]

Tertiaries and "Oblates (regular)" are laypersons who live according to the third rule of orders such as those of the Secular Franciscan Order or Lay Carmelites, either within a religious community or outside.[172] The Church recognizes several other forms of consecrated life, including secular institutes, societies of apostolic life and consecrated widows and widowers.[175] It also makes provision for the approval of new forms.[179]

Membership

Membership of the Catholic Church is attained through baptism.[180] For those baptized as children, First Communion is a rite of passage when, following instruction, they are allowed to receive the sacrament of the Eucharist for the first time in the Latin (Western) Church; the Eastern Churches confer the sacraments of initiation at once – Baptism, Chrismation (Confirmation) and Eucharist – to unbaptized children or unbaptized adult converts. Adults who have never been baptized may be admitted to Baptism by participating in a formation program such as the Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults.[181] Christians – those baptized with flowing water and in the "Name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit" – baptized outside of the Catholic Church are admitted through other formation programs but are not re-baptized.[182]

Members of the Church can incur excommunication for serious violations of ecclesiastical law. Excommunication does not remove a member from the Church but severely limits the member's ability to participate in it. For very serious offenses, the excommunication can be incurred automatically.[183] Examples include violating the seal of confession (committed when a priest discloses the sins heard in the sacrament of Penance), persisting in heresy, creating schism, becoming an apostate, or having or performing an abortion.[184] Excommunication is the most severe ecclesiastical penalty because it forbids a person from receiving any sacrament. Such offences can only be forgiven by the Pope, the bishop of the diocese where the person resides, or a priest authorized by the bishop to do so.[185] A similar concept is a minister's power to refuse to distribute communion to a person not yet declared excommunicated (but nonetheless excommunicated latae sententiae) who has publicly committed a very serious sin.[186]

Excommunication, which is a "medicinal" measure meant to lead to repentance, does not make the person to whom it is applied cease to be a member of the Church. To terminate one's membership, a person must present to the competent Church authority a formal act of defection. If that person later wishes to rejoin the Church, the procedure is the same as for any baptized non-Catholic, namely by a profession of faith, again before the competent Church authority.

Cultural influence

The Catholic Church has been very influential in the development of European and world history.[29] Today, the Catholic Church has more than a billion members, over half of all Christians[note 8] and approximately one-sixth of the world's population, although the number of practicing Catholics worldwide is not reliably known.[191] In addition, the Church played a significant role in moderating some of the excesses of the colonial era.[192][193][194][195] Over the course of its history, the Church has influenced the status of women, condemning infanticide, divorce, incest, polygamy and counting the marital infidelity of men as equally sinful to that of women.[192][193][196]

Catholic universities, scholars and many priests including Nicolaus Copernicus, Roger Bacon, Albertus Magnus, Robert Grosseteste, Nicholas Steno, Francesco Grimaldi, Giambattista Riccioli, Roger Boscovich, Athanasius Kircher, Gregor Mendel, Georges Lemaître and others, were responsible for many important scientific discoveries. The Jesuits produced the large majority of priest-scientists, who contributed to worldwide cultural exchange by spreading their developments in knowledge to Asia, Africa, and the Americas.[197][198] Most research took place in Catholic universities that were staffed by members of religious orders who had the education and means to conduct scientific investigation.[197] The 1633 Church condemnation of Galileo Galilei created the perception of antagonism between the Church and science of that era. According to historian Thomas Noble, the effect of the Galileo affair was to restrict scientific development in some European countries.[197] In part because of lessons learned from the Galilei affair, the Church created the Pontifical Academy of Sciences in 1603. This scientific organization reached its present form by 1936.[199] Today, the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, is a body whose international membership includes Stephen Hawking and Nobel laureates such as Charles Hard Townes among many others, and which provides the pope with valuable insights into scientific matters.[199]

The Catholic Church was the dominant influence on the development of Western art, at least up to the Protestant Reformation. Important contributions include its consistent opposition to Byzantine iconoclasm, its cultivation and patronage of individual artists, as well as development of the Romanesque, Gothic and Renaissance styles of art and architecture.[200] Renaissance artists such as Raphael, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Bernini, Botticelli, Fra Angelico, Tintoretto, Caravaggio, and Titian, were among a multitude of innovative virtuosos sponsored by the Church.[201] In music, Catholic monks developed the first forms of modern Western musical notation in order to standardize liturgy throughout the worldwide Church,[202] and an enormous body of religious music has been composed for it through the ages. This led directly to the emergence and development of European classical music, and its many derivatives. The Baroque style, which encompassed music, art, and architecture, was particularly encouraged by the post-Reformation Catholic Church as such forms offered a means of religious expression that was stirring and emotional, intended to stimulate religious fervor.[203]

History

Early Christianity

The Catholic Church considers Pentecost to be the beginning of its own history.[204][205] According to historians, the Apostles traveled to northern Africa, Asia Minor, Arabia, Greece, and Rome to found the first Christian communities,[204][206] over 40 of which had been established by the year 100.[207] The New Testament gospels indicate that the earliest Christians continued to observe traditional Jewish pieties such as fasting, reverence for the Torah and observance of Jewish holy days.[208][209] However, Christians were directed by Jesus to evangelize non-Jewish peoples. As Christianity spread to non-Jews, disputes over observance of the Mosaic law generated intense controversy. A pivotal moment in this dispute occurred in the mid-1st century, when the circumcision controversy arose and was ultimately addressed at the Council of Jerusalem. At this council, Paul made an argument that circumcision was no longer necessary, vocally supported by Peter, as documented in Acts 15. This position received widespread support and was summarized in a letter circulated in Antioch.[210] In the second century, writings by teachers such as Ignatius of Antioch and Irenaeus defined Catholic teaching in stark opposition to Gnosticism.[211] Other writers such as Pope Clement I, Justin Martyr, Augustine of Hippo influenced the development of Church teachings and traditions. These writers and others are collectively known as Church Fathers.[212]

Persecution

Early Christians refused to offer sacrifices to the Roman gods or to worship Roman rulers as gods and were thus subject to persecution.[213] The first documented case of imperially-sponsored persecution of Christians occurred in Rome under Nero in the first century and re-occurred under various emperors until the great persecution of Diocletian and Galerius, which was seen as a final attempt to wipe out Christianity.[214] Nevertheless, Christianity continued to spread and was eventually legalized in 313 under Constantine's Edict of Milan.[215]

During this era of persecution, the early Church evolved both in doctrinal and structural ways. The apostles had convened the first Church council, the Council of Jerusalem, to resolve issues concerning evangelization of Gentiles.[67] While competing forms of Christianity emerged early, the Roman Church retained this practice of meeting in "synods" (councils) to ensure that any internal doctrinal differences were quickly resolved, which facilitated broad doctrinal unity within the mainstream churches.[66][216] By 58 AD, a large Christian community existed in Rome.[217] From as early as the first century, the Church of Rome was recognized as a doctrinal authority because it was believed that the Apostles Peter and Paul had led the Church there.[50][218][219] The concept of the primacy of the Roman bishop over other churches was increasingly recognized by the church at large from at least the second century although disputes over the implications of that primacy would ultimately lead to schisms.[220][221]

State religion of the Roman Empire

Despite persecution, Christianity spread and was eventually legalized in 313 under Constantine's Edict of Milan.[215] In 303, the schismatic Donatist Church had been created in North Africa in a dispute over the authority of bishops who handed over religious books and sacrificed to Roman gods during the persecution of Christians by Diocletian.[222] In 380, Catholic Christianity was declared the state religion of the Empire.[223] The Donatists were thus treated as heretics and in 412 an edict was passed allowing for their property to be confiscated and their leaders exiled. The Donatist Church quickly went into decline and disappeared completely by the end of the sixth century.[224]

After the legalization of Christianity, a number of doctrinal disputes led to the calling of ecumenical councils. The doctrinal formulations resulting from these ecumenical councils were pivotal in the history of Christianity. The first seven Ecumenical Councils, from the First Council of Nicaea (325) to the Second Council of Nicaea (787), sought to reach an orthodox consensus and to establish a unified Christendom. In 325, the First Council of Nicaea convened in response to the rise of Arianism, the belief that Jesus had not existed eternally but was a divine being created by and therefore inferior to God the Father.[225] In order to encapsulate the basic tenets of the Christian belief, it promulgated a creed which became the basis of what is now known as the Nicene Creed.[226] In addition, it divided the church into geographical and administrative areas called dioceses.[227] The Council of Rome in 382 established the first Biblical canon when it listed the accepted books of the Old and New Testament.[228] The Council of Ephesus in 431[229] and the Council of Chalcedon in 451 defined the relationship of Christ's divine and human natures, leading to splits with the Nestorians and Monophysites.[66]

Constantine moved the imperial capital to Constantinople, and the Council of Chalcedon (AD 451) elevated the See of Constantinople to a position "second in eminence and power to the bishop of Rome".[230][231] From c 350 to c500, the bishops, or popes, of Rome steadily increased in authority.[217] Rome had particular prominence over the other dioceses; it was considered the see of Peter and Paul, it was located in the capital of the Western Roman Empire, it was wealthy and known for supporting other churches, and church scholars wanted the Roman bishop's support in doctrinal disputes.[232]

Early Middle Ages

Following the collapse of Roman power in Western Europe, the Catholic faith competed with Arianism for the conversion of the barbarian tribes.[233] The 496 conversion of Clovis I, pagan king of the Franks, marked the beginning of a steady rise of the Catholic faith in the West.[234] The Rule of St Benedict, composed in 530, became a blueprint for the organization of monasteries throughout Europe.[235] As well as providing a focus for spiritual life, the new monasteries preserved classical craft and artistic skills while maintaining intellectual culture within their schools, scriptoria and libraries. They also functioned as agricultural, economic and production centers, particularly in remote regions, becoming major conduits of civilization.[236]

Pope Gregory the Great reformed church practice and administration around 600 and launched renewed missionary efforts[237] which were complemented by other missionary movements such as the Hiberno-Scottish mission.[238][239] Missionaries such as Augustine of Canterbury, Saint Boniface, Willibrord and Ansgar took Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons and other Germanic people.[238] In the same period the Visigoths and Lombards moved from Arianism toward Catholicism,[234] and in Britain the full reunion of the Celtic churches with Rome was effectively marked by the Synod of Whitby in 664.[239] Later missionary efforts by Saints Cyril and Methodius in the ninth century reached greater Moravia and introduced, along with Christianity, the Cyrillic alphabet used in the southern and eastern Slavic languages.[240] While Christianity continued to expand in Europe, Islam presented a significant military threat to Western Christendom.[241] By 715, Muslim armies had conquered Syria, Jerusalem, Caesarea, Alexandria, Iraq and Persia, Carthage and much of the Iberian Peninsula.[242]

From the 8th century, Iconoclasm, the destruction of religious images, became a major source of conflict in the eastern church.[243][244] Byzantine emperors Leo III and Constantine V strongly supported Iconoclasm, while the papacy and the western church remained resolute in favour of the veneration of icons. In 787, the Second Council of Nicaea ruled in favor of the iconodules but the dispute continued into the early 9th century.[244] The consequent estrangement led to the creation of the papal states and the papal coronation of the Frankish King Charlemagne as Emperor of the Romans in 800. This ultimately created a new problem as successive Western emperors sought to impose an increasingly tight control over the popes.[245][246]

Eastern and Western Christendom grew farther apart in the 9th century. Conflicts arose over ecclesiastical jurisdiction in the Byzantine-controlled south of Italy, missionaries to Bulgaria and a brief schism revolving around Photios of Constantinople.[243][247] Further disagreements led to Pope and Patriarch excommunicating each other in 1054, commonly considered the date of the East–West Schism.[248] The Western branch of Christianity remained in communion with the Pope and remained a part of the Catholic Church, while the Eastern (Greek) branch that rejected the papal claims became known as the Eastern Orthodox churches.[249][250] Efforts to mend the rift were attempted at the Second Council of Lyon in 1274 and Council of Florence in 1439. While in each case the Eastern Emperor and Eastern Patriarch both agreed to the reunion,[251] neither council changed the attitudes of the Eastern Churches at large, and the schism remained.[252]

High Middle Ages

The Cluniac reform of monasteries that had begun in 910 sparked widespread monastic growth and renewal.[253] Monasteries introduced new technologies and crops, fostered the creation and preservation of literature and promoted economic growth. Monasteries, convents and cathedrals still operated virtually all schools and libraries.[254][255] Despite a church ban on the practice of usury the larger abbeys functioned as sources for economic credit.[256] The 11th and 12th century saw internal efforts to reform the church. The college of cardinals in 1059 was created to free papal elections from interference by Emperor and nobility. Lay investiture of bishops, a source of rulers' dominance over the Church, was attacked by reformers and under Pope Gregory VII, erupted into the Investiture Controversy between Pope and Emperor. The matter was eventually settled with the Concordat of Worms in 1122 where it was agreed that bishops would be selected in accordance with Church law.[257][258]

In 1095, Byzantine emperor Alexius I appealed to Pope Urban II for help against renewed Muslim invasions,[259] which caused Urban to launch the First Crusade aimed at aiding the Byzantine Empire and returning the Holy Land to Christian control.[252][260] The goal was not permanently realized, and episodes of brutality committed by the armies of both sides left a legacy of mutual distrust between Muslims and Western and Eastern Christians.[261] The sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade, conducted against papal authorisation, left Eastern Christians embittered and was a decisive event that permanently solidified the schism between the churches.[262][263]

The crusades also saw the formation of military orders which included the Hospitallers, Templars and later, the Teutonic Knights all of whom provided social services as well as guardianship of pilgrim routes.[264] The Teutonic Knights conquered the then-pagan Prussia.[264] The Templars became noted bankers and creditors who were suppressed by King Philip IV of France shortly after 1300.[265] Later, mendicant orders were founded by Francis of Assisi and Dominic de Guzmán which brought consecrated religious life into urban settings.[266] These orders also played a large role in the development of cathedral schools into universities, the direct ancestors of the modern Western institutions.[267] Notable scholastic theologians such as the Dominican Thomas Aquinas worked at these universities, his Summa Theologica was a key intellectual achievement in its synthesis of Aristotelian thought and Christianity.[268]

Twelfth century France witnessed the emergence of Catharism, a dualist heresy that had spread from Eastern Europe through Germany. After the Cathars were accused of murdering a papal legate in 1208,[269] Pope Innocent III declared the Albigensian Crusade against them. When this turned into an "appalling massacre",[270] he instituted the first papal inquisition to prevent further massacres and to root out the remaining Cathars.[270][271][272] Formalized under Gregory IX, this Medieval inquisition put to death an average of three people per year for heresy.[265][272]

Over time, other inquisitions were launched by secular rulers to prosecute heretics, often with the approval of Church hierarchy, to respond to the threat of Muslim invasion or for political purposes.[273] King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain formed an inquisition in 1480, originally to deal with distrusted converts from Judaism and Islam to Catholicism.[274] Over a 350-year period, this Spanish Inquisition executed between 3,000 and 4,000 people,[275] representing around two percent of those accused.[276] In 1482 Pope Sixtus IV condemned the excesses of the Spanish Inquisition, but Ferdinand ignored his protests.[277] Some historians argue that for centuries Protestant propaganda and popular literature exaggerated the horrors of the inquisitions in an effort to associate the Catholic Church with acts committed by secular rulers.[278][279][280] Over all, one percent of those tried by the inquisitions received death penalties, leading some scholars to consider them rather lenient when compared to the secular courts of the period.[275][281] The inquisition played a major role in the final expulsion of Islam from Sicily and Spain.[241]

In the 14th century, the Papacy came under French dominance, with Clement V in 1305 moving to Avignon.[282] The Avignon Papacy ended in 1376 when the Pope returned to Rome[283][284] but was soon followed in 1378 by the 38-year-long Western schism with separate claimants to the papacy in Rome, Avignon and (after 1409) Pisa, backed by conflicting secular rulers.[285] The matter was finally resolved in 1417 at the Council of Constance where the three claimants either resigned or were deposed and held a new election naming Martin V Pope.[285]

Reformation and Counter-Reformation

John Wycliffe and Jan Hus crafted the first of a new series of disruptive religious perspectives that challenged the Church. The Council of Constance (1414–1417), condemned Hus and ordered his execution, but could not prevent the Hussite Wars in Bohemia. In 1509, the scholar Erasmus wrote In Praise of Folly, a work which captured the widely held unease about corruption in the Church.[286] The Council of Constance, the Council of Basel and the Fifth Lateran Council had all attempted to reform internal Church abuses but had failed.[287] As a result, rich, powerful and worldly men like Roderigo Borgia (Pope Alexander VI) were able to win election to the papacy.[287][288] Personal corruption and abuses of power by these men and other members of the hierarchy preceded the Protestant Reformation - which began as an attempt to reform the Catholic Church from within. Catholic reformers opposed the ecclesiastic malpractice - especially the sale of indulgences, and simony, the selling of clerical offices — which they saw as evidence of systemic corruption of the Church’s hierarchy. Subsequently, reformers began to assault many of the historic doctrinal teachings of the Church.

In 1517, Martin Luther included his Ninety-Five Theses in a letter to several bishops.[289][290] His theses protested key points of Catholic doctrine as well as the sale of indulgences.[289][290] Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin, and others further criticized Catholic teachings. These challenges developed into a large and all encompassing European movement called the Protestant Reformation.[232][291]

In Germany, the reformation led to a nine-year war between the Protestant Schmalkaldic League and the Catholic Emperor Charles V. In 1618 a far graver conflict, the Thirty Years' War, followed.[292] In France, a series of conflicts termed the French Wars of Religion were fought from 1562 to 1598 between the Huguenots and the forces of the French Catholic League. The St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre marked the turning point in this war.[293] Survivors regrouped under Henry of Navarre who became Catholic and began the first experiment in religious toleration with his 1598 Edict of Nantes.[293] This Edict, which granted civil and religious toleration to Protestants, was hesitantly accepted by Pope Clement VIII.[292][294]

The English Reformation under Henry VIII began more as a political than as a theological dispute. When the annulment of his marriage was denied by the pope, Henry had Parliament pass the Acts of Supremacy, 1534, which made him, and not the pope, head of the English Church.[295][296] Although he strove to maintain the substance of traditional Catholicism, Henry initiated and supported the confiscation and dissolution of monasteries, friaries, convents and shrines throughout England, Wales and Ireland.[295][297][298] Under Henry's daughter, Mary I, England was reunited with Rome, {Henry's Act of Supremacy was repealed (1554)}, but the following monarch, Elizabeth I, {second Act of Supremacy, 1558} restored a separate church which outlawed Catholic priests[299] and prevented Catholics from educating their children and taking part in political life[300][301] until the first Catholic Relief Act of 1778 began the process of eliminating many of the anti-Catholic laws.[302][303]

The Catholic Church responded to doctrinal challenges and abuses highlighted by the Reformation at the Council of Trent (1545–1563), which became the driving force of the Counter-Reformation. Doctrinally, it reaffirmed central Catholic teachings such as transubstantiation, and the requirement for love and hope as well as faith to attain salvation.[304] It also made structural reforms, most importantly by improving the education of the clergy and laity and consolidating the central jurisdiction of the Roman Curia.[304][305][306][note 9] To popularize Counter-Reformation teachings, the Church encouraged the Baroque style in art, music and architecture,[203] and new religious orders were founded. These included the Theatines, Barnabites and Jesuits, some of which became the great missionary orders of later years.[309] The Jesuits quickly took on a leadership in education during the Counter-Reformation, viewing it as a "battleground for hearts and minds";[310] at the same time, the writings of figures such as Teresa of Avila, Francis de Sales and Philip Neri spawned new schools of spirituality within the Church.[311]

Toward the latter part of the 17th century, Pope Innocent XI reformed abuses that were occurring in the Church's hierarchy, including simony, nepotism and the lavish papal expenditures that had caused him to inherit a large papal debt.[312] He promoted missionary activity, tried to unite Europe against the Turkish invasion, prevented influential Catholic rulers (including the Emperor) from marrying Protestants but strongly condemned religious persecution.[312]

Age of Discovery

Many of the countries leading the exploration and colonization of the Age of Discovery were Catholic and thus explorers and missionaries were responsible for the spread of Catholicism to the Americas, Asia, Africa and Oceania. Pope Alexander VI had awarded colonial rights over most of the newly discovered lands to Spain and Portugal[313] and the ensuing patronato system allowed state authorities, not the Vatican, to control all clerical appointments in the new colonies.[314][315] Although the Spanish monarchs tried to curb abuses committed against the Amerindians by explorers and conquerors,[316] Antonio de Montesinos, a Dominican friar, openly rebuked the Spanish rulers of Hispaniola in 1511 for their cruelty and tyranny in dealing with the American natives.[317][318] King Ferdinand enacted the Laws of Burgos and Valladolid in response. The issue resulted in a crisis of conscience in 16th-century Spain[318][319] and, through the writings of Catholic clergy such as Bartolomé de Las Casas and Francisco de Vitoria, led to debate on the nature of human rights[318] and to the birth of modern international law.[320][321] Enforcement of these laws was lax, and some historians blame the Church for not doing enough to liberate the Indians; others point to the Church as the only voice raised on behalf of indigenous peoples.[322] Nevertheless, Amerindian populations suffered serious decline due to new diseases, inadvertently introduced through contact with Europeans, which created a labor vacuum in the New World.[316]

In 1521 the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan made the first Catholic converts in the Philippines.[323] Elsewhere, Portuguese missionaries under the Spanish Jesuit Francis Xavier evangelized in India, China, and Japan.[324] Church growth in Japan came to a halt in 1597 when the Shogunate, in an effort to isolate the country from foreign influences, launched a severe persecution of Christians or Kirishitan's.[325] An underground minority Christian population survived throughout this period of persecution and enforced isolation which was eventually lifted in the 19th century.[325][326]

In China, despite Jesuit efforts to find compromise, the Chinese Rites controversy led the Kangxi Emperor to outlaw Christian missions in 1721.[327] These events added fuel to growing criticism of the Jesuits, who were seen to symbolize the independent power of the Church, and in 1773 European rulers united to force Pope Clement XIV to dissolve the order.[328] The Jesuits were eventually restored in the 1814 papal bull Sollicitudo omnium ecclesiarum.[329]

In the Californias, Franciscan priest Junípero Serra founded a series of missions.[330] In South America, Jesuit missionaries sought to protect native peoples from enslavement by establishing semi-independent settlements called reductions.

Enlightenment

From the seventeenth century onward, a philosophical and cultural movement known as "the Enlightenment" attacked the power and influence of the Church over Western society.[331] Eighteenth century writers such as Voltaire and the Encyclopedists wrote biting critiques of both religion and the Church. One target of their criticism was the 1685 revocation of the Edict of Nantes by King Louis XIV which ended a century-long policy of religious toleration of Protestant Huguenots.

During the French revolution, the Church was abolished, monasteries destroyed, 30,000 priests exiled and hundreds killed.[332] In 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Italy, imprisoning Pope Pius VI, who died in captivity. Napoleon later re-established the Catholic Church in France through the Concordat of 1801.[333] The end of the Napoleonic wars brought Catholic revival and the return of the Papal States.[334][335][334]

Pope Gregory XVI challenged the power of the Spanish and Portuguese monarchs by appointing his own candidates as colonial bishops. He also condemned slavery and the slave trade in the 1839 papal bull In Supremo Apostolatus, and approved the ordination of native clergy in the face of government racism.[336]

Industrial age

The neutrality of this section is disputed. |

In response to growing concern about the deteriorating working and living conditions brought about by the Industrial Revolution, Pope Leo XIII published the encyclical Rerum Novarum. This set out Catholic social teaching in terms that rejected socialism but advocated the regulation of working conditions, the establishment of a living wage and the right of workers to form trade unions.[337]

Although the infallibility of the Church in doctrinal matters had always been a Church dogma, the First Vatican Council, which convened in 1870, affirmed the doctrine of papal infallibility when exercised in certain specifically defined pronouncements.[338][339] This decision gave the pope "enormous moral and spiritual authority over the worldwide" Church.[331] Reaction to the pronouncement resulted in the breakaway of a group of mainly German churches which subsequently formed the Old Catholic Church.[340] The loss of the papal states to the Italian unification movement created what came to be known as the Roman Question,[341] a territorial dispute between the papacy and the Italian government that was not resolved until the 1929 Lateran Treaty granted sovereignty to the Holy See over Vatican City.[342]

By the close of the 19th century, European powers had managed to gain control of most of the African interior.[343] The new rulers introduced cash-based economies which created an enormous demand for literacy and a western education—a demand which for most Africans could only be satisfied by Christian missionaries.[343] Catholic missionaries followed colonial governments into Africa, and built schools, hospitals, monasteries and churches.[343] In Latin America, a succession of anti-clerical regimes came to power beginning in the 1830s.[344] Church properties were confiscated, bishoprics were left vacant, religious orders suppressed,[345][346] the collection of clerical tithes ended,[347] and clerical dress in public prohibited.[348] One such regime emerged in Mexico in 1860. The regime's Calles Law eventually led to the "worst guerilla war in Latin American History", the Cristero War.[349] Between 1926 and 1934, over 3,000 priests were exiled or assassinated.[350][351] In an effort to prove that "God would not defend the Church", Calles ordered Church desecrations where services were mocked, nuns were raped and captured priests were shot.[349] Despite the persecution, the Catholic Church survived and prospered; nearly 90 percent of Mexicans identified as Catholic in 2001.[352]

In the twentieth century, confiscation of Church properties and restrictions on people's religious freedoms generally accompanied secularist and Marxist-leaning governmental reforms[vague].[353] The Soviet Union saw persecution of the Church and Catholics[354] continue well into the 1930s. In addition to executing and exiling many clerics, monks and laymen, the confiscating of Church implements and the closing of churches were common.[355] During the 1936–39 Spanish Civil War, in which Republicans and anarchists destroyed Church property and killed an estimated 6,800 priests and members of religious orders,[356][357] the Catholic hierarchy supported Francisco Franco's rebel Nationalist forces against the elected government,[358] citing the violence and persecution directed against it.[359] In 1953, a concordat was signed making Catholicism the official religion of Spain.

After persecution and some violence against Church institutions and some Catholics[vague], the Catholic Church and Nazi Germany signed the Reichskonkordat (July 1933) which guaranteed the Church some protections and rights in exchange for dissolution of the Catholic political party.[dubious – discuss][361][362] When the persecutions continued in violation of this agreement Pope Pius XI issued the 1937 encyclical Mit brennender Sorge[361][363][364][365] which publicly condemned Nazi persecution of the Church, Nazi leaders,[who?] and their ideology of neopaganism and the culture of racial superiority.[365][366][367][368]

After the Second World War began in September 1939, the Church condemned the invasion of Poland and subsequent 1940 Nazi invasions.[369] In the Holocaust, Pope Pius XII directed the Church hierarchy to help protect Jews from the Nazis.[370] While Pius XII has been credited with helping to save "hundreds of thousands of Jews", by , for example, the prominent Israeli historian Pinchas Lapide and Conservative rabbi David G. Dalin,[371] the Church has also been accused of encouraging centuries of antisemitism and Pius himself of not doing enough to stop Nazi atrocities.[372][373] Debate over the validity of these criticisms continues to this day,[374][371][375] In 2000 Pope John Paul II on behalf of all people, apologized to Jews by inserting a prayer at the Western Wall.[376]

In accordance with Soviet doctrine regarding the exercise of religion, postwar Communist governments in Eastern Europe severely restricted religious freedoms. Even though some clerics collaborated with the Communist regimes,[377] the Church's resistance and the leadership of Pope John Paul II have been credited with hastening the downfall of communist governments across Europe in 1991.[378] The rise to power of the Communists in China in 1949 led to the expulsion of all foreign missionaries.[379] The new government also created the Patriotic Church whose unilaterally appointed bishops were initially rejected by Rome before many of them were accepted.[379][380][381] The Cultural Revolution of the 1960s led to the closure of all religious establishments. When Chinese churches eventually reopened they remained under the control of the Patriotic Church. Many Catholic pastors and priests continued to be sent to prison for refusing to renounce allegiance to Rome.[380]

Second Vatican Council and beyond

The Catholic Church initiated a comprehensive process of reform under Pope John XXIII.[382] Intended as a continuation of the First Vatican Council, the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), developed into an engine of modernization, making pronouncements on religious freedom, the nature of the Church and the mission of the laity.[382] The role of the bishops of the Church was brought into renewed prominence, especially when seen collectively, as the college of the successors of the Apostles in teaching and governing the Church. It also permitted the Latin liturgical rites to use vernacular languages as well as Latin during Mass and other sacraments.[383] Christian unity became a greater priority.[384] In addition to finding more common ground with the various Protestant denominations, the Catholic Church has reopened discussions regarding the possibility of reconciliation between the Eastern Orthodox churches and the Catholic Church.[385] In October 2009, the Vatican announced the creation of new ecclesiastical structures to receive Anglican converts to the Catholic Church.[386][387]

Changes to old rites and ceremonies following Vatican II produced a variety of responses. Although most Catholics "accepted the changes more or less gracefully", some stopped going to church and others tried to preserve what they perceived to be the "true precepts of the Church".[388] The latter form the basis of today's Traditionalist Catholic groups, which believe that the reforms of Vatican II have gone too far. Liberal Catholics form another dissenting group, and feel that the Vatican II reforms did not go far enough.[389]

In the 1960s, growing social awareness and politicization in the Church in Latin America gave birth to liberation theology, a movement often identified with Gustavo Gutiérrez who was pivotal in expounding the melding of Marxism and Catholic social teaching. A cornerstone of the Liberation Theology were ecclesial base communities, groups uniting clergy and laity in social and political action. Although the movement garnered some support among Latin American bishops, it was never officially endorsed by any of the Latin American Bishops’ Conferences. At the 1979 Conference of Latin American Bishops in Puebla, Mexico, Pope John Paul II and conservative bishops attending the conference attempted to rein in the more radical elements of liberation theology; however, the conference did make a formal commitment to a "preferential option for the poor".[390] Archbishop Óscar Romero, a supporter of the movement, became the region's most famous contemporary martyr in 1980, when he was murdered by forces allied with the government of El Salvador while saying Mass.[391] In Managua, Nicaragua, Pope John Paul II criticized elements of Liberation Theology and the Nicaraguan Catholic clergy's involvement in the Sandinista National Liberation Front.[392] Pope John Paul II maintained that the Church, in its efforts to champion the poor, should not do so by advocating violence or engaging in partisan politics.[393] Liberation Theology is still alive in Latin America today, although the Church now faces the challenge of Pentecostal revival in much of the region.[392]

The sexual revolution of the 1960s precipitated Pope Paul VI's 1968 encyclical Humanae Vitae (On Human Life) which rejected the use of contraception, including sterilization, asserting that these work against the intimate relationship and moral order of husband and wife by directly opposing God's will.[394] It approved Natural Family Planning as a legitimate means to limit family size.[394] In line with Catholic teachings on sexual morality, the Church focuses on partner fidelity rather than the use of condoms as the primary means of preventing the transmission of AIDS.[395] This stance has been criticized by many public health officials and AIDS activists[395][396][397] although some research suggests that partner fidelity combined with access to condoms has proved more effective in stopping the spread of AIDS in Africa.[398] Abortion was condemned by the Church as early as the first century, again in the fourteenth century and again in 1995 with Pope John Paul II's encyclical Evangelium Vitae (Gospel of Life).[399] This encyclical condemned the "culture of death" which the pope often used to describe the societal embrace of contraception, abortion, euthanasia, suicide, capital punishment, and genocide.[399][400] Feminists disagreed with these and other Church teachings and, with a coalition of American nuns, called on the Church to consider the ordination of women.[401] They stated that many Church documents contained anti-female prejudice and studies were conducted to discover how this may have developed as it was deemed contrary to the openness of Jesus.[401] These events led Pope John Paul II to issue the 1988 apostolic letter Mulieris Dignitatem (On the Dignity of Women), which declared that women had a different, yet equally important role in the Church.[402][403] In 1994 the apostolic letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis (On Ordination to the Priesthood) further explained that the Church follows the example of Jesus, who chose only men for the specific priestly duty.[157][404][405]

Since the end of the twentieth century, sex abuse by Catholic clergy has been the subject of media coverage, legal action, and public debate in Australia, Ireland, the United States, Canada and other countries.[406]

Present day Church

Catholic institutions, personnel and demographics

The neutrality of this section is disputed. |

| Institutions | |

|---|---|

| Parishes and missions | 408,637 |

| Primary and secondary schools | 125,016 |

| Universities | 1,046 |

| Hospitals | 5,853 |

| Orphanages | 8,695 |

| Homes for the elderly and handicapped | 13,933 |

| Dispensaries, leprosaries, nurseries and other institutions | 74,936 |

| Total | 638,116 |

| Personnel | |

| Seminarians (men studying for the priesthood) | 110,583 |

| Religious sisters | 769,142 |

| Religious brothers | 55,057 |

| Diocesan and religious priests | 405,178 |

| Lay Ecclesial Ministers | 30,632 |

| Permanent deacons | 27,824 |

| Bishops | 3,475 |

| Archbishops | 914 |

| Cardinals | 183 |

| Pope | 1 |

| Total | 1,402,989 |

Church membership in 2007 was 1.147 billion people,[408] increasing from the 1950 figure of 437 million[409] and the 1970 figure of 654 million.[410] The Catholic population increase of 139% outpaced the world population increase of 117% between 1950 and 2000.[409] It is the largest Christian church, and encompasses over half of all Christians, one sixth of the world's population, the largest organized body of any world religion.[189][411] It is known for its ability to use its transnational ties and organizational strength to bring significant resources to needy situations[citation needed] and operates the world's largest non-governmental school system.[412] Although the number of practicing Catholics worldwide is not reliably known,[191] membership is growing particularly in Africa and Asia.[vague][188]

The Vatican announced that the number of priests had increased, as of 2005, from 405,891 to 406,411, although Europe and America saw a slight decrease.[vague][413][414] Since 2000, the number of priests has been steadily rising each year,[vague] a turnaround from the previous two decades which had seen a 3.7% drop, in worldwide priests mainly due to decreases in the US and Europe.[vague][415][416][417][418][419]

Some parts of Europe and the Americas have experienced a shortage of priests in recent years as the number of priests has not increased in proportion to the number of Catholics.[420] The Church in Latin America, known for its large parishes where the parishioner to priest ratio is the highest in the world, considers this to be a contributing factor in the rise of Pentecostal and evangelical Christian denominations in the region.[421] Secularism has seen a steady rise in Europe, yet the Catholic presence there remains strong.[vague][421]

With a high number of adult baptisms, the Church is growing faster in Africa than anywhere else.[vague][422] Because of what it cites as a greater need, it also operates a greater number of Catholic schools per parish here (three schools per parish) than in other areas of the world.[423] Challenges faced include suppression of non-Islamic religious practices by Muslims in Sudan and a high rate of AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa.[424]

The Church in Asia is a significant minority among other religions, comprising only 3% of all Asians, yet it has a large proportion of religious sisters, priests and parishes relative to the total Catholic population.[421] From 1975 to 2000, total Asian population grew by 61% with an Asian Catholic population increase of 104%.[425] Challenges faced include oppression in communist countries like North Korea and China,[426] prohibition in Muslim countries like Saudi Arabia, and violence in mixed religion countries such as Iraq and India.

In Oceania, the Church faces challenges in reaching indigenous populations where over 715 different languages are spoken.[421]

Of Catholics worldwide, 12% live in Africa, 50% in the Americas, 10% in Asia, 27% in Europe and 1% in Oceania.[427]

Pope Benedict XVI