Deepwater Horizon oil spill

This article documents a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (May 2010) |

| Deepwater Horizon oil spill | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Location | Gulf of Mexico near Mississippi River Delta |

| Coordinates | 28°44′12″N 88°23′14″W / 28.73667°N 88.38716°W |

| Date | April 20, 2010 - present (5299 days) |

| Cause | |

| Cause | Wellhead blowout |

| Casualties | 17 injured 11 missing, presumed dead |

| Operator | Transocean under lease for BP [1] |

| Spill characteristics | |

| Volume | up to 100,000 barrels (4,200,000 US gal) per day |

| Area | 2,500 to 9,100 sq mi (6,500 to 23,600 km2) [2] |

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill, also called the BP Oil Spill, the Gulf of Mexico oil spill or the Macondo blowout,[3][4][5][6] is a massive ongoing oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. The spill stems from a sea floor oil gusher that started with an oil well blowout on April 20, 2010. The blowout caused a catastrophic explosion on the Deepwater Horizon offshore oil drilling platform that was situated about 40 miles (64 km) southeast of the Louisiana coast. The explosion killed 11 platform workers and injured 17 others.[7] The gusher originates from a deepwater oil well 5,000 feet (1,500 m) below the ocean surface. Estimates of the amount of oil being discharged range from BP's current estimate of over 5,000 barrels (210,000 US gallons; 790,000 litres) to as much as 100,000 barrels (4,200,000 US gallons; 16,000,000 litres) of crude oil per day. The exact spill flow rate is uncertain – in part because BP has refused to allow independent scientists to perform accurate measurements[8] – and is a matter of ongoing debate. The resulting oil slick covers a surface area of at least 2,500 square miles (6,500 km2), with the exact size and location of the slick fluctuating from day to day depending on weather conditions.[9] Scientists have also discovered immense underwater plumes of oil not visible from the surface.

BP (formerly British Petroleum) is the operator and principal developer of the Macondo Prospect oil field, which was thought to hold as much as 50 million barrels (7.9×106 m3) of oil prior to the blowout, by BP's own estimate.[10] BP is the lead stakeholder, with a 65% working interest in the project; Anadarko Petroleum Corporation and a division of Mitsui each hold minority shares. The Deepwater Horizon drilling platform had been leased by BP from its owner, Transocean Ltd.[11] The U.S. Government has named BP as the responsible party in the incident and officials have said the company will be held accountable for all cleanup costs resulting from the oil spill.[12][13] BP has accepted responsibility for the oil spill and the cleanup costs, but indicated they are not at fault as the platform was run by Transocean personnel.[14] It is the third serious incident at a BP-run site in the United States in the last five years, following the Texas City Refinery explosion in 2005, and the Prudhoe Bay oil spill in 2006. These previous incidents, attributed to lapses in safety and maintenance, have contributed to the damage to BP's reputation and market valuation since the spill.[15][16]

The spill is thought to have eclipsed the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill as the largest in US history.[17] Experts fear that due to factors such as petroleum toxicity and oxygen depletion, it will result in an environmental disaster, damaging the Gulf of Mexico fishing industry, tourism industry, and habitat of hundreds of bird species.[18][19] Crews are working to block off bays and estuaries, using anchored barriers, floating containment booms, and sand-filled barricades along shorelines. There are a variety of ongoing efforts, both short and long term, to contain the leak and stop spilling additional oil into the Gulf.

Background

Deepwater Horizon

The Deepwater Horizon was a floating oil drilling platform — a fifth-generation, ultra-deepwater, dynamically positioned, column-stabilized, semi-submersible Mobile Offshore Drilling Unit (MODU). The platform was 396 feet (121 m) long and 256 feet (78 m) wide and could operate in waters up to 8,000 feet (2,400 m) deep, to a maximum drill depth of 30,000 feet (9,100 m).[20] The $560 million platform[21][22] was built by Hyundai Heavy Industries in South Korea and completed in 2001. It was owned by Transocean, and was under lease to BP until September 2013.[11][23] At the time of the explosion, the Deepwater Horizon was on Mississippi Canyon Block 252, referred to as the Macondo Prospect, in the United States sector of the Gulf of Mexico, about 41 miles (66 km) off the Louisiana coast.[24][25][26] The platform commenced drilling in February 2010 at a water depth of approximately 5,000 feet (1,500 m).[27] The planned well was to be drilled to 18,000 feet (5,500 m), and was to be plugged and abandoned for subsequent completion as a subsea producer.[27]

Explosion and fire

The fire aboard the Deepwater Horizon reportedly started at 9:45 p.m. CST on April 20, 2010.[28] Survivors described the incident as a sudden explosion which gave them less than five minutes to escape as the alarm went off.[29] Video of the fire shows billowing flames, taller than a multistory building, and a captain of a rescue boat described the heat as so intense that it was melting the paint off the boats.[30] After burning for more than a day, Deepwater Horizon sank on April 22, 2010.[31] The Coast Guard stated to CNN on April 22 that they received word of the sinking at approximately 10:21 am.[32] At an April 30 press conference, BP said that it did not know the cause of the explosion.[33]

Adrian Rose, a vice president of Transocean, Ltd., said workers had been performing their standard routines and had no indication of any problems prior to the explosion.[34] At the time of the explosion the rig was drilling an exploratory well.[35] Production casing was being run and cemented at the time of the accident. Once the cementing was complete, it was due to be tested for integrity and a cement plug set to temporarily abandon the well for later completion as a subsea producer.[36] Halliburton has confirmed that it cemented the Macondo well but had not set the final cement plug to cap the bore as "operations had not reached a stage where a final plug was needed".[37] A special nitrogen-foamed cement was used which is more difficult to handle than standard cement.[38] Halliburton said that it had finished cementing 20 hours before the fire.[39] Transocean executive Adrian Rose said the event was basically a blowout.[36]

According to interviews with platform workers conducted during BP's internal investigation, a bubble of methane gas escaped from the well and shot up the drill column, expanding quickly as it burst through several seals and barriers before exploding.[40] Transocean chief executive Steven Newman described the cause as "a sudden, catastrophic failure of the cement, the casing or both."[38] According to Transocean executive Adrian Rose, abnormal pressure accumulated inside the marine riser and as it came up it "expanded rapidly and ignited".[36] The heavy drilling mud in the pipes initially held down the gas of the leaking well. When managers believed they were almost done with the well, they decided to displace the mud with seawater; the gas was then able to overcome the weight of the fluid column and rose to the top.[38]

Casualties and rescue efforts

Nine crew members on the platform floor and two engineers died during the explosion.[40] According to officials, 126 individuals were on board, of whom 79 were Transocean employees, six were from BP, and 41 were contracted; of these, 115 individuals were evacuated.[34] Most of the workers evacuated the rig and took diesel-powered fiberglass lifeboats to the M/V Damon B Bankston, a workboat that BP had hired to service the rig.[41][42] Seventeen others were then evacuated from the workboat by helicopter.[34] Most survivors were brought to Port Fourchon for a medical check-up and to meet their families.[43] Although 94 workers were taken to shore with no major injuries, four were transported to another vessel, and 17 were sent to trauma centers in Mobile, Alabama and Marrero, Louisiana.[34] Most were soon released.[34][34][44][45] A group of BP executives were on board the platform celebrating the project's safety record when the blowout occurred;[46] they were injured but survived.[40]

Initial reports indicated that between 12 to 15 workers were missing.[23][47] The United States Coast Guard launched a massive rescue operation involving two cutters, four helicopters and a rescue plane.[48] Two Coast Guard cutters continued searching overnight. By the morning of April 22 the Coast Guard had surveyed nearly 1,940 miles (3,120 km) in 17 separate air and sea search missions.[41] On April 23, the Coast Guard called off the search for the 11 missing persons, concluding that the "reasonable expectations of survival" had passed.[44][44][49] Officials concluded that the missing workers may have been near the blast and not been able to escape the sudden explosion.[50]

The 11 men killed in the explosion were: Jason Anderson, 35, Midfield, Texas; Aaron Dale Burkeen, 37, Philadelphia, Mississippi; Donald Clark, 34, Newellton, Louisiana; Stephen Curtis, 39, Georgetown, Louisiana; Gordon Jones, 28, Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Roy Wyatt Kemp, 27, Jonesville, Louisiana; Karl Klepping, 38, Natchez, Mississippi; Dewey Revette, 48, State Line, Mississippi; Shane Roshto, 22, Franklin County, Mississippi; Blair Manuel, 56, Eunice, Louisiana; and Adam Weise, 24, Yorktown, Texas. [51][52]

Investigation

On April 22, 2010, the United States Coast Guard and the Minerals Management Service launched an investigation of the possible causes of the explosion.[36] On May 11, 2010, the Obama administration requested the National Academy of Engineering conduct an independent technical investigation to determine the root causes of the disaster so that corrective steps could be taken to address the mechanical failures underlying the accident.[53] The United States House Committee on Energy and Commerce asked Halliburton to brief it as well as provide any documents it might have related to its work on the Macondo well.[37]

Attention has focused on the cementing procedure and the blowout preventer, which failed to fully engage.[38] A number of significant problems have been identified with the blowout preventer: There was a leak in the hydraulic system that provides power to the shear rams. The underwater control panel had been disconnected from the bore ram, and instead connected to a test hydraulic ram. The blowout preventer schematic drawings, provided by Transocean to BP, do not correspond to the structure that is on the ocean bottom. The shear rams are not designed to function on the joints where the drill pipes are screwed together or on tools that are passed through the blowout preventer during well construction. The explosion may have severed the communication line between the rig and the sub-surface blowout preventer control unit such that the blowout preventer would have never received the instruction to engage. Before the backup dead man's switch could engage, communications, power and hydraulic lines must all be severed, but it is possible hydraulic lines were intact after the explosion. Of the two control pods for the deadman switch, the one that has been inspected so far had a dead battery.[54] A rigorous investigation will reveal the series of errors that came together to cause the blowout; preliminary findings from BP’s internal investigation released by the House Committee on Energy and Commerce on May 25 indicated several serious warning signs in the hours just prior to the explosion.[55][56] The chief mechanic on the rig testified on May 26 that the BP company man overruled Transocean employees and insisted on displacing protective drilling mud with seawater, just hours before the explosion, stating, "the company man said, 'Well, this is how it's gonna be,' and the tool-pusher, driller and OIM reluctantly agreed."[57]

In other testimony, the Minerals Management Service officials said there have been 39 fires or explosions offshore in the Gulf of Mexico in the first five months of 2009, the last period with statistics available.[34][45] There had been numerous previous spills and fires on the Deepwater Horizon, which had been issued citations by the Coast Guard 18 times between 2000 and 2010. The previous fires were not considered unusual for a Gulf platform and have not been connected to the April 2010 explosion and spill.[39] The Deepwater Horizon did, however, have other serious incidents including a 2008 incident where 77 people were evacuated from the platform after it listed over and began to sink after a section of pipe was accidentally removed from the platform's ballast system.[58] According to a report by 60 Minutes, the blowout preventer was damaged in a previously unreported accident four weeks before the April 20 explosion, and BP overruled the drilling operator on key operations. BP declined to comment on the report.[59] Chief surveyor John David Forsyth of the American Bureau of Shipping testified in hearings before the Joint Investigation[60] of the of the Minerals Management Service and the U.S. Coast Guard investigating the causes of the explosion that his agency last inspected the rig's failed blowout preventer in 2005.[61]

Pre-spill precautions

In February 2009, BP filed a 52-page exploration and environmental impact plan for the Macondo well with the Minerals Management Service, an arm of the United States Department of the Interior that oversees offshore drilling. The plan stated that it was "unlikely that an accidental surface or subsurface oil spill would occur from the proposed activities"[62] In the event an accident did take place the plan stated that due to the well being 48 miles (77 km) from shore and the response capabilities that would be implemented, no significant adverse impacts would be expected.[62] The Department of the Interior exempted BP's Gulf of Mexico drilling operation from a detailed environmental impact study after concluding that a massive oil spill was unlikely.[63][64]

The BP wellhead had been fitted with a blowout preventer (BOP), but it was not fitted with remote-control or acoustically-activated triggers for use in case of an emergency requiring a platform to be evacuated. It did have a dead man's switch designed to automatically cut the pipe and seal the well if communication from the platform is lost, but it was unknown whether the switch activated.[65] Regulators in both Norway and Brazil generally require acoustically-activated triggers on all offshore platforms, but when the Minerals Management Service considered requiring the remote device, a report commissioned by the agency as well as drilling companies questioned its cost and effectiveness.[65] In 2003, the agency determined that the device would not be required because drilling rigs had other back-up systems to cut off a well.[65][66]

Discovery of oil spill

On the morning of April 22, 2010, CNN quoted Coast Guard Petty Officer Ashley Butler as saying that "oil was leaking from the rig at the rate of about 8,000 barrels (340,000 US gallons; 1,300,000 litres) of crude per day."[67] That afternoon, as a large oil slick spread, Coast Guard Senior Chief Petty Officer Michael O'Berry used the same figure. Two Remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs) were sent down to attempt to cap the well, but had been unsuccessful.[32] Butler warned of a leak of up to 700,000 US gallons (17,000 bbl) of diesel fuel, and BP Vice President David Rainey termed the incident as being a potential "major spill."[32]

On April 22, BP announced that it was deploying a remotely operated underwater vehicle to the site to assess whether oil was flowing from the well.[68] Other reports indicated that BP was using more than one remotely operated underwater vehicle and that the purpose was to attempt to plug the well pipe.[69] On April 23, a remotely operated underwater vehicle reportedly found no oil leaking from the sunken rig and no oil flowing from the well.[70] Coast Guard Rear Admiral Mary Landry expressed cautious optimism of zero environmental impact, stating that no oil was emanating from either the wellhead or the broken pipes and that oil spilled from the explosion and sinking was being contained.[71][72][73][74] The following day, April 24, Landry announced that a damaged wellhead was indeed leaking oil into the Gulf and described it as "a very serious spill".[75]

Volume and extent of oil spill

Spill flow rate

BP initially estimated that the wellhead was leaking 1,000 barrels (42,000 US gallons; 160,000 litres) a day.[75] On April 28, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimated that the leak was likely 5,000 barrels (210,000 US gallons; 790,000 litres) a day, five times larger than initially estimated by BP.[76][77] According to BP, estimating the flow is very difficult as there is no metering of the flow underwater.[77] The company has refused to allow scientists to perform more accurate, independent measurements of the flow, claiming that it isn't relevant to the response and such efforts might distract from the response.[8] In their permit to drill the well, registered officially with the MMS, BP estimated the worst case flow at 162,000 barrels (6,800,000 US gallons; 25,800,000 litres) per day.[78][79].

Early estimates of the flow by outside experts were considerably higher than those of BP and NOAA. Geologist and oil industry consultant John Amos said a more realistic figure was 20,000 barrels (840,000 US gallons; 3,200,000 litres) a day.[80] Other sources using satellite imagery put the number as high as 25,000 barrels (1,000,000 US gallons; 4,000,000 litres) a day.[75][81] Oceanographer Ian MacDonald agreed with that estimate, and said that (as of May 2, 2010) the oil slick might already contain more than 210,000 barrels (8,800,000 US gal).[82]

On May 12, BP released a 30 second video of the spill at the site of the broken pipe. Experts contacted by National Public Radio and shown underwater footage of oil and gas gushing out of the broken pipe put the leak rate substantially higher.[83] Timothy Crone, an associate research scientist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, used another well-accepted method to calculate fluid flows, estimating "at least 50,000 barrels (2,100,000 US gallons; 7,900,000 litres) a day" leaking from the well. Eugene Chaing, a professor of astrophysics at the University of California, Berkeley, arrived at a figure approximating Crone's findings, stating, "I would peg [the flow] at around 20,000 barrels (840,000 US gallons; 3,200,000 litres) to 100,000 barrels (4,200,000 US gallons; 16,000,000 litres) per day." [84]

Steven Wereley, an associate professor at Purdue University used a computer analysis (particle image velocimetry) to arrive at a rate of 70,000 barrels (2,900,000 US gallons; 11,000,000 litres) per day (plus or minus 20%).[85][86] However, after watching a video of the leak, on May 19 he said, "I can't say how much in excess of that 70,000 this leak is, but I would use the word 'considerable'".[87] In Congressional testimony, Werely stated that oil is escaping at the rate of 95,000 barrels (4,000,000 US gallons; 15,100,000 litres) a day, 19 times greater than the 5,000 barrels (210,000 US gallons; 790,000 litres) a day estimate BP and government scientists have been citing.[88] Massachusetts Democratic Representative Ed Markey, chair of the Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming, has voiced strong criticism of BP stating, "BP has mismanaged this entire incident from day one. They should not be trusted.", and, "It's obvious they are trying to limit information to protect their economic liability."[89] On May 20, after telling BP they would host live feed of the spill that was already being provided to Congress if the company itself could or would not, United States lawmakers streamed live video of the Gulf oil spill from 5,000 feet (1,500 m) below sea level.[90]

Spill area

The spread of the oil was increased by strong southerly winds caused by an impending cold front. By April 25, the oil spill covered 580 square miles (1,500 km2) and was only 31 miles (50 km) from the ecologically sensitive Chandeleur Islands.[91] An April 30 estimate placed the total spread of the oil at 3,850 square miles (10,000 km2).[92] The spill quickly approached the Delta National Wildlife Refuge and Breton National Wildlife Refuge, where dead animals, including a sea turtle, were found.[93][94][95] On May 14, the AP reported that a publicly available model called the Automated Data Inquiry for Oil Spills indicates about 35 percent of a hypothetical 114,000 barrels (4,800,000 US gal) spill of light Louisiana crude oil released in conditions similar to those found in the Gulf now would evaporate, that between 50 percent and 60 percent of the oil would remain in or on the water, and the rest would be dispersed in the ocean. In the same report, Ed Overton says he thinks most of the oil is floating within 1 foot (30 cm) of the surface.[96] The New York Times is tracking the size of the spill over time using data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the US Coast Guard and Skytruth.[97]

Underwater oil plumes

On May 13, Robert Bea, who serves on a National Academy of Engineering panel on oil pipeline safety, said, "There's an equal amount that could be subsurface too," and that the oil below the surface "is damn near impossible to track." Also on May 13, Garland Robinette from New Orleans reported on NBC News that tarballs about the size of softballs —Template:In to cm circumference— were washing up on the shores of three Louisiana parishes and may be coming in from under the surface of the water.[98]

On May 15, researchers from the University of Southern Mississippi aboard the research vessel RV Pelican identified enormous oil plumes in the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico, including one as large as 10 miles (16 km) long, 3 miles (4.8 km) wide and 300 feet (91 m) thick in spots. The shallowest oil plume the group detected was at about 2,300 feet (700 m), while the deepest was near the seafloor at about 4,200 feet (1,300 m). Other researchers from the University of Georgia have found that the oil may occupy multiple layers "three or four or five layers deep". The New York Times speculates that the undetermined amount of hydrocarbons in these underwater plumes may explain why satellite images of the ocean surface have calculated a flow rate of only 5,000 barrels (210,000 US gal) a day, whereas studies of video of the gushing oil well have variously calculated that it could be flowing at a rate of 25,000–80,000 barrels (1,000,000–3,400,000 US gal) a day.[8]

In an interview on May 19, marine biologist Rick Steiner said that the likelihood of extensive undersea plumes of oil droplets should have been anticipated from the moment the spill began, given that such an effect from deepwater blowouts had been predicted in the scientific literature for more than a decade and had been confirmed in a test off the coast of Norway. He criticized the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration for not setting up an extensive sampling program to map and characterize the plumes in the first days of the spill.[99]

Expansion predictions

Some unspecified scientists predict that the Gulf Stream could pick up the oil and carry it around Florida to the East Coast, but on May 5, Robert Weisberg of The University of South Florida said winds would take the oil away from the Loop Current, which becomes the Gulf Stream. Ruoying He of North Carolina State University, head of the Ocean Observing and Monitoring Group, said if the oil reached the Gulf Stream, then south Florida, including the Keys, would likely be affected. Whether it comes ashore farther north depends on local winds, but the Gulf Stream moves away from the coast southeast of Charleston, South Carolina, at a formation called the Charleston Bump. Susan Lozier of Duke University said in late spring off the Carolinas, the winds would blow away from the shore. Rich Luettich, director of the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City, said the oil could remain a problem for as much as a year, or even longer. He did say in the unlikely event the oil reached North Carolina's coast, the Outer Banks would provide significant protection.[100]

On May 19, scientists monitoring the spill with the European Space Agency Envisat radar satellite stated that oil reached the Loop Current, which flows clockwise around the Gulf of Mexico towards Florida, and may reach Florida within 6 days. The scientists warn that because the Loop Current is a very intense, deep ocean current, its turbulent waters will accelerate the mixing of the oil and water in the coming days. "This might remove the oil film on the surface and prevent us from tracking it with satellites, but the pollution is likely to affect the coral reef marine ecosystem".[101] National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration acknowledged, on May 19, that "a small portion of the oil slick has reached the Loop Current in the form of light to very light sheens."[102]

Independent monitoring of contamination

Wildlife and environmental groups accused BP of holding back information about the extent and impact of the growing slick, and urged the White House to order a more direct federal government role in the spill response. In prepared testimony for a congressional committee, National Wildlife Federation President Larry Schweiger said BP had failed to disclose results from its tests of chemical dispersants used on the spill, and that BP had tried to withhold video showing the true magnitude of the leak.[103]

On May 20, 2010 United States Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar indicated that the U.S. government will verify how much oil has leaked into the Gulf of Mexico.[104] On the same day, the heads of the Environmental Protection Agency and the United States Department of Homeland Security told BP chief executive Tony Hayward in a letter that the company had "fallen short" of its promises to keep the public and the federal government informed about the spill, writing that "BP must make publicly available any data and other information related to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill that you have collected." Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lisa P. Jackson and United States Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano asked for the results of tests looking for traces of oil and dispersant chemicals in the waters of the gulf. BP did not respond Thursday to requests for comment about the letter, the Washington Post reported in a story titled, "Estimated rate of oil spill no longer holds up."[105]

On May 19, 2010, BP established a live feed of the oil spill to meet the requests of the Chairman of the House Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming, Edward J. Markey.[106] This decision was made after hearings in Congress accused the company of withholding data from the ocean floor and of blocking efforts by independent scientists to come up with estimates for the amount of crude flowing into the Gulf each day.[107]

On May 18, 2010, CBS reporter Kelly Cobiella tried to visit the beaches in the Gulf of Mexico to report on the disaster. She was met by BP contractors and American Coast Guard officers who threatened her with arrest if she did not leave. The Coast Guard officials specified that they were acting under the authority of BP.[108]

Activities to stop the oil leak

The rig's blowout preventer, a fail-safe device fitted at source of the well, did not automatically cut off the oil flow as intended when the explosion occurred. BP attempted to use remotely operated underwater vehicles to close the blowout preventer valves on the well head 5,000 feet (1,500 m) below sea level, a valve-closing procedure taking 24–36 hours.[91][109] BP engineers predicted it would take six attempts to close the valves.[110] As of May 2, 2010, they had sent six remotely operated underwater vehicles to close the blowout preventer valves, but all attempts were ultimately unsuccessful.[111]

Oil was known to be leaking into the gulf from three different locations. On May 5, BP announced that the smallest of three known leaks had been capped. This did not reduce the oil flowing from leak, but it did allow the repair group to focus their efforts on the two remaining leaks.[112]

Short-term efforts

BP engineers have attempted a number of techniques to control or stop the oil spill. The first and fastest was to place a subsea oil recovery system over the well head. This involved placing a 125-tonne (276,000 lb) container dome over the largest of the well leaks and piping it to a storage vessel on the surface.[113] This option was untested at such depths.[113] BP deployed the system on May 7–8 but it failed when gas leaking from the pipe combined with cold water to form methane hydrate crystals that blocked up the steel canopy at the top of the dome.[114] The excess buoyancy of the crystals clogged the opening at the top of the dome where the riser was to be connected.

Following the failure, a smaller containment dome, dubbed a "top hat", was lowered to the seabed.[115] The dome was lowered on May 11 but is currently being kept away from the leaking oil well.[115] The dome is meant to funnel some of the escaping oil to a waiting tanker on the surface. Like the first containment dome, the dome has been deployed successfully in the past but not at such a depth.[115] The 4 feet (1.2 m) wide and 5 feet (1.5 m) tall "top hat" dome is much smaller than the first containment dome, which was 40 feet (12 m) tall and 125-tonne (276,000 lb).[115] The "top hat" dome will be deployed in the event that BP fails to control the spill by inserting a 6-inch (150 mm) diameter tube inside the leaking pipe.[114]

On May 14, engineers began the process of positioning a riser insertion tube tool at the largest oil leak site.[114] After three days, BP reported the tube was working.[116] Since then, collection rates have varied daily between 1,000 and 5,000 barrels (42,000 and 210,000 US gallons; 160,000 and 790,000 litres), the average being 2,000 barrels (84,000 US gallons; 320,000 litres) a day, as of May 21.[117][118] The collected gas rate ranges between 4 and 17 million cubic feet per day (110×103 and 480×103 m3/d). The oil is being stored and gas is being flared on the board of drillship Discoverer Enterprise.[119]

BP will try to shut down the well completely using a technique called "top kill".[120] The process involves pumping heavy drilling fluids through two 3-inch (7.6 cm) lines into the blowout preventer that sits on top of the wellhead. This would first restrict the flow of oil from the well, which then could be sealed permanently with cement.[59]The top kill procedure, approved by the Coast Guard on May 25, commenced at 1 p.m. CDT on May 26 and, according to BP sources, while failure could be evident in minutes or hours it may take "a day or two" before its success could be determined. [121]

Long-term efforts

BP is drilling relief wells into the original well to enable them to block it. Once the relief wells reach the original borehole, the operator will pump drilling mud into the original well to stop the flow of oil. Transocean's Development Driller III has started drilling a first relief well on May 2, and Development Driller II has started drilling a second relief on May 23.[122][123][124] This operation will take two to three months to stop the flow of oil and will cost about US$100 million.[125]

Containment and cleanup

BP, which was leading the cleanup, initially employed remotely operated underwater vehicles, 700 workers, four airplanes and 32 vessels to contain the oil.[75] After the discovery that the undersea wellhead was leaking, the oil cleanup was hampered by high waves on April 24 and 25.[91] According to BP Chief Executive, Tony Hayward, BP will compensate all those affected by the oil spill saying that "We are taking full responsibility for the spill and we will clean it up and where people can present legitimate claims for damages we will honor them. We are going to be very, very aggressive in all of that."[126]

On April 28, the US military announced it was joining the cleanup operation.[77] Doug Suttles, chief operating officer of BP, welcomed the assistance of the US military.[77] The same day, the US Coast Guard announced plans to corral and burn off up to 1,000 barrels (42,000 US gallons; 160,000 litres) of oil on the surface each day. It tested how much environmental damage a small, controlled burn of 100 barrels (4,200 US gallons; 16,000 litres) did to surrounding wetlands, but could not proceed with an open seas burn due to poor conditions.[127][128] By April 29, 69 vessels including skimmers, tugs, barges and recovery vessels were active in cleanup activities. On 30 April, President Barack Obama announced that he had dispatched the Secretaries of Department of Interior and Homeland Security, as well as the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to the Gulf Coast to assess the disaster.[129] The director of the United States Geological Survey, Marcia McNutt, is leading a team of scientists who are tasked with providing the government with an independent scientific assessment of the scope of the disaster and of BP's efforts to stop the flow of oil.[130][131]

In an attempt to minimize impact to sensitive areas in the Mississippi River Delta area more than 100,000 feet (30 km) of containment booms were deployed along the coast.[132] By the next day, this nearly doubled to 180,000 feet (55 km) of deployed booms, with an additional 300,000 feet (91 km) staged or being deployed.[133] On May 2, high winds and rough waves rendered oil-catching booms largely ineffective.[134]

As of April 30, approximately 2,000 people and 79 vessels were involved in the response and BP claimed that more than 6,300,000 US gallons (150,000 barrels) of oil-water mix had been recovered.[92] On May 4, the U.S Coast Guard estimated that 170 vessels, and nearly 7,500 personnel were involved in the cleanup efforts, with an additional 2,000 volunteers assisting.[135] On May 26, all of the commercial fishing boats helping in the clean up and recovery process were ordered ashore. A total of 125 commercial vessels which had been outfitted with equipment for oil recovery operations were recalled after some workers began experiencing health problems.[136]

The type of oil involved is also a major problem. While most of the oil drilled off Louisiana is a lighter crude, because the leak is deep under the ocean surface the leaking oil is a heavier blend which contains asphalt-like substances, and, according to Ed Overton, who heads a federal chemical hazard assessment team for oil spills, this type of oil emulsifies well, making a "major sticky mess". Once it becomes that kind of mix, it no longer evaporates as quickly as regular oil, does not rinse off as easily, cannot be eaten by microbes as easily, and does not burn as well. "That type of mixture essentially removes all the best oil clean-up weapons", Overton and others said.[137]

On May 21, 2010, Plaquemines Parish president Billy Nungesser publicly complained about the federal government's hindrance of local mitigation efforts. State and local officials had proposed building sand berms off the coast to catch the oil before it reached the wetlands, but the emergency permit request had not been answered for over two weeks. The following day Nungesser complained that the plan had been vetoed, while Army Corps of Engineers officials claimed that the request was still under review.[138] Gulf Coast Government officials have released water via the Mississippi River diversions in effort to create an outflow of water that would keep the oil off the coast. The water from these diversions comes from the entire Mississippi watershed. Even with this approach, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is predicting a "massive" landfall to the west of the Mississippi River at Port Fourchon.[139]

On May 23, 2010, Louisiana Attorney General Buddy Caldwell wrote a letter to Lieutenant General Robert L. Van Antwerp of the US Army Corps of Engineers[140], stating that Louisiana has the right to dredge sand to build barrier islands to keep the oil spill from its wetlands without the approval of the Corps, as the 10th Amendment to the Constitution does not grant the federal government the authority to deny a state the right to act in an emergency.[141][142] He also wrote that if the Corps "persists in its illegal and ill-advised efforts" to prevent the state from building the barriers that he would advise Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindall to proceed with the plans and challenge the Corps in court.[143]

Dispersants

On May 1, two United States Department of Defense C-130 Hercules aircraft were employed to spray oil dispersant.[144] Corexit EC9500A and Corexit EC9527A are the main oil dispersants being used.[145] These contain propylene glycol, 2-butoxyethanol and a proprietary organic sulfonic acid salt.[146] On May 7, Secretary Alan Levine of the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals, Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality Secretary Peggy Hatch, and Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries Secretary Robert Barham sent a letter to BP outlining their concerns related to potential dispersant impact on Louisiana's wildlife and fisheries, environment, aquatic life, and public health. Officials are also requesting BP release information on the effects of the dispersants they are using to combat the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.[147]

Federal regulators have approved the injection of dispersants directly at the leak to break apart the oil before it reaches the surface.[148] The Environmental Protection Agency approved the use of dispersants to break up the oil, after three underwater tests.[149] By May 15, 436,000 US gallons (1,650,000 L) of Corexit EC9500A and EC9527A had been released into the Gulf. These products are neither the least toxic, nor the most effective, among the dispersants approved by the Environmental Protection Agency,[149] and they are banned from use on oil spills in the United Kingdom.[150] Twelve other products received better toxicity and effectiveness ratings,[151] but BP says it chose to use Corexit because it was available the week of the rig explosion.[149] Critics contend that the major oil companies stockpile Corexit because of their close business relationship with Nalco.[149][152] By 20 May, BP had applied 600,000 US gallons (2,300,000 L) of Corexit on the surface and 55,000 US gallons (210,000 L) underwater.[153]

Independent scientists have suggested that the underwater injection of Corexit into the leak might be responsible for the plumes of oil discovered below the surface.[151] However, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration administrator Jane Lubchenco said that there was no information supporting this conclusion, and indicated further testing would be needed to ascertain the cause of the undersea oil clouds.[151]

On May 19, the Environmental Protection Agency gave BP 24 hours to choose less toxic alternatives to Corexit. The alternative(s) had to be selected from the list of Environmental Protection Agency -approved dispersants on the National Contingency Plan Product Schedule with application beginning within 72 hours of Environmental Protection Agency approval of their choices, or provide a "detailed description of the alternative dispersants investigated, and the reason they believe those products did not meet the required standards.".[154][155] On May 20, US Polychemical Corporation reportedly received an order from BP for Dispersit SPC 1000, a dispersant it manufactures. US Polychemical stated it was able to produce 20,000 US gallons (76,000 L) a day in the first few days and increasing up to 60,000 US gallons (230,000 L) a day thereafter.[156] BP spokesman Scott Dean said Friday, May 20, that BP had responded to the Environmental Protection Agency directive with a letter "that outlines our findings that none of the alternative products on the Environmental Protection Agency 's National Contingency Plan Product Schedule list meets all three criteria specified in yesterday's directive for availability, toxicity and effectiveness." [157] BP has so far refused to offer an acceptable "detailed description of the alternatives investigated and the reason they believe those products did not meet the required standards" on a public Web site, as called for in a letter sent on May 20 by Department of Homeland Security Secretary Janet Napolitano and Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lisa P. Jackson to BP CEO Tony Hayward, claiming such full disclosure would compromise its confidential business information.[158][159] In a press conference on May 24, EPA administrator Lisa P. Jackson said the 700,000 US gallons (2,600,000 L) of dispersants already used was "approaching a world record" and that “dissatisfied with BP’s response” she was ordering the EPA to conduct their own evaluation of alternatives to Corexit, while ordering BP to take “immediate steps to scale back the use of dispersants.”[160][161][162]

Consequences

Ecological effects

More than 400 species live in the islands and marshlands at risk, including the endangered Kemp's Ridley turtle. In the national refuges most at risk, about 34,000 birds have been counted, including gulls, pelicans, roseate spoonbills, egrets, terns, and blue herons.[92] Since April 30, 19 dead dolphins, none of which have had visible signs of oiling, have been found within the designated spill area.[163] Samantha Joye of the University of Georgia indicated that the oil could harm fish directly, and microbes used to consume the oil would also add to the reduction of oxygen in the water, with effects being felt higher up the food chain.[116] According to Joye, it could take the ecosystem years and possibly decades to recover from such an infusion of oil and gas.[164] On Tuesday May 18, 2010, BP chief executive Tony Hayward insisted the environmental impact of the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico will be "very, very modest".[165]

It is possible the Gulf Stream sea currents may spread the oil into the Atlantic Ocean.[166] If oil follows the Loop Current to the east coast of the United States, it could impact wildlife even without the oil reaching the beaches. Duke University marine biologist Larry Crowder said threatened loggerhead turtles on Carolina beaches could swim out into contaminated waters. Sea birds, mammals, and dolphins could also be affected. Ninety percent of North Carolina's commercially valuable sea life spawn off the coast and could be contaminated if oil reaches the area. Douglas Rader, a scientist for the Environmental Defense Fund, said prey could be negatively affected as well. Steve Ross of UNC-Wilmington said coral reefs off the East Coast could be smothered by too much oil.[167]

Impact on fisheries

On April 29, 2010, Governor of Louisiana Bobby Jindal declared a state of emergency in the state after weather forecasts predicted the slick would reach the Louisiana coast.[168] By April 30, the Coast Guard received reports that oil had begun washing up to wildlife refuges and seafood grounds on the Louisiana Gulf Coast.[169] The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration expanded a fishing ban in the Gulf of Mexico because of the spreading oil. On May 19, heavy oil from the spill began to make landfall along fragile Louisiana marshlands.[170] By May 20 oil had reached populated areas of the Louisiana coast.[171]On May 24, the federal government declared a fisheries disaster for the states of Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana.[172]

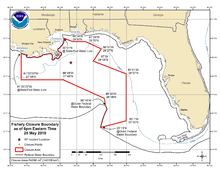

An emergency shrimping season was opened on April 29, 2010, so that a catch could be brought in before the oil advanced too far.[173] On May 2, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration closed commercial and recreational fishing in affected federal waters between the mouth of the Mississippi River and Pensacola Bay. The closure initially incorporated 6,814 square miles (17,650 km2).[174] The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration increased the area under a fishing band to 6,814 square miles (17,650 km2) on May 7, 45,728 square miles (118,430 km2) on May 18 and 54,096 square miles (140,110 km2) on May 25.[175][176][177][178] On May 22, The Louisiana Seafood Promotion and Marketing Board stated said 60 to 70 percent of oyster and blue crab harvesting areas and 70 to 80 percent of fin-fisheries remained open.[179] The Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals closed an additional ten oyster beds on May 23, just south of Lafayette, Louisiana, citing confirmed reports of oil along the state's western coast.[180]

Financial impacts

Initial cost estimates to the fishing industry were $2.5 billion, while the impact on tourism along Florida's Paradise Coast could be $3 billion.[169]

On May 25, BP reported that its own expenditures on the oil spill had reached $760 million, a figure that excludes claims from fishermen and other affected industries.[181] The price tag for the spill was rising by at least $10 million a day.[182] An April 30 Merrill Lynch report found that five companies connected to the disaster, BP, Transocean, Anadarko Petroleum, Halliburton and Cameron International, had lost a total of $21 billion in market capitalization since the explosion.[183] Currently, the United States Oil Pollution Act of 1990 limits BP's liability for non-cleanup costs to $75 million unless gross negligence is proven.[184] BP has said it would pay for all cleanup and remediation regardless of whether the statutory liability cap. Nevertheless, some Democratic lawmakers are seeking to pass legislation that would increase the liability limit to $10 billion.[185] Analysts for Swiss Re have estimated that the total insured losses from the accident could reach $3.5 billion. However, according to UBS, the final bill could be as much as $12 billion.[181] Even more recently, the Guardian printed an article that suggests that the fine may well be as high as $60 Billion. While the maximum civil penalty per barrel normally is $1,100, in cases of gross negligence this is increased to $4,300 per barrel spilled. In the worst case estimate of the amount of oil being spilled daily (115,000 barrels), and assuming it will take two months for BP to fix the leak, this would amount to $60 Billion.[186]

Litigation

On April 22, the families of two missing workers filed lawsuits in federal and state court in Louisiana against BP and Transocean, alleging negligence and failure to meet federal regulations.[187] Since then, more than 130 lawsuits relating to the spill have been filed.[181] According to Michael Stag, a lawyer for the Louisiana Environmental Action Network, the cases are likely to be combined into one court (as a multidistrict litigation) for evidence gathering and pretrial decisions.[188] BP, Transocean, Cameron International, and Halliburton Energy Services have all been named in one or more of the lawsuits.[188] Because the spill has been largely lingering offshore, the plaintiffs who can claim damages so far are mostly out-of-work fishermen and tourist resorts that are receiving cancellations."[189] The oil company says 23,000 individual claims have already been filed, of which 9,000 have so far been settled.[181] BP and Transocean want the cases to be heard in Houston, seen as friendly to the oil business. Some plaintiffs want the case heard in Louisiana, while others prefer Mississippi or Florida.[189] Several New Orleans judges have recused themselves from hearing oil spill cases because of stock ownership in companies involved or other conflicts of interest.[190] BP has retained a major law firm, Kirkland & Ellis, to defend most of the lawsuits arising from the oil spill.

U.S. and Canadian offshore drilling policy

Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar stated that the disaster would have huge ramifications for energy development in the oceans all around the world.[128] Salazar ordered immediate inspections of all deep-water operations in the Gulf of Mexico. An Outer Continental Shelf safety review board within the Department of the Interior will provide recommendations for conducting drilling activities in the Gulf.[37] The United States will not be issuing new offshore drilling leases until a thorough review determines whether more safety systems are needed.[191]

On April 28, the National Energy Board of Canada, which regulates offshore drilling in the Canadian Arctic and along the British Columbia Coast, issued a letter to oil companies asking them to explain their argument against safety rules which require same-season relief wells.[192] Five days later, the Canadian Minister of the Environment Jim Prentice said the government would not approve a decision to relax safety or environment regulations for large energy projects.[193] On May 3, Governor of California Arnold Schwarzenegger withdrew his support for a proposed plan to allow expanded offshore drilling projects in California.[194][195]

Atlantis Oil Field safety practices

The Deepwater Horizon disaster has given new impetus to an effort by Rep. Raúl M. Grijalva (D-AZ) and 18 fellow Democrats to pressure the Minerals Management Service to investigate safety practices on the BP offshore platform in the Atlantis Oil Field. According to Common Dreams NewsCenter, a whistleblower report to the Minerals Management Service in March 2009 that was confirmed by an independent expert, said that "a BP database showed that over 85 percent of the Atlantis Project's Piping and Instrument drawings lacked final engineer-approval, and that the project should be immediately shut down until those documents could be accounted for and are independently verified."[196] According to Grijalva, "MMS and congressional staff have suggested that while the company by law must maintain 'as-built' documents, there is no requirement that such documents be complete or accurate."[197] BP and other oil industry groups wrote letters objecting to a proposed Minerals Management Service rule last year that would have required stricter safety measures.[198] The Minerals Management Service changed rules in April 2008 to exempt certain projects in the central Gulf region, allowing BP to operate in the Macondo Prospect without filing a "blowout" plan.[199]

National Commission on BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill

On May 22, 2010 President Obama announced that he has signed an executive order establishing the bipartisan National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling, with former Florida Governor and Senator Bob Graham and former Environmental Protection Agency Administrator William K. Reilly serving as co-chairs. The purpose of the commission is to "consider the root causes of the disaster and offer options on safety and environmental precautions."[200][201]

See also

- List of oil spills

- Ixtoc I oil spill - the largest previous oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico

- Offshore oil and gas in the US Gulf of Mexico

- Oil Pollution Act of 1990

- Atlantis PQ - BP-owned oil platform under scrutiny since this spill

Notes

- ^ The New York Times, May 5, 2010; National Public Radio, May 3, 2010.

- ^ AP wire story, May 1, 2010; Reuters wire story, May 3, 2010.

- ^ Whitehouse press release, May 5, 2010.

- ^ Environment News Service, May 13, 2010. "Gulf gusher Dwarfs Previous Estimates, BP Will Inject Junk to Plug It."

- ^ "BP 'army' battles Macondo flow". Upstream Online. 2010-05-10. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- ^ "Interpreting NOAA's Trajectory Prediction Maps for the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill" (PDF). NOAA. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ USA Today, Memorial Services Honors 11 Dead Oil Rig Workers, May 25 2010, accessed May 26 2010, http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2010-05-25-oil-spill-victims-memorial_N.htm

- ^ a b c The New York Times, May 15, 2010. "BP has resisted entreaties from scientists that they be allowed to use sophisticated instruments at the ocean floor that would give a far more accurate picture of how much oil is really gushing from the well."

- ^ Reuters wire story, May 3, 2010. "The giant oil slick ... is now estimated to be at least 130 miles (210 km) by 70 miles (110 km), or about the size of the state of Delaware."

- ^ Klump, Edward (2010-05-13). "Spill May Hit Anadarko Hardest as BP's Silent Partner". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- ^ a b Reddall, Braden (2010-04-22). "Transocean rig loss's financial impact mulled". Reuters. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ "Salazar: Oil spill 'massive' and a potential catastrophe". CNN. 2010-05-02. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ "Guard mobilized, BP will foot bill". Politico. Capitol News Company LLC. 2010-05-01. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ "Fire booms neglected in oil cleanup?". MSNBC. 2010-05-03. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ Krauss, Clifford (29 April 2010). "Oil Spill's Blow to BP's Image May Eclipse Costs". The New York Times. New York.

- ^ Wade Goodwyn (2010-05-06). "Previous BP Accidents Blamed On Safety Lapses". All Things Considered. 5:06 minutes in. National Public Radio.

{{cite episode}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|episodelink=,|city=, and|serieslink=(help) - ^ See unanimous British coverage:

- ^ ""Bird Habitats Threatened by Oil Spill" from National Wildlife". Nwf.org. 2010-04-30. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ Gulf Oil Slick Endangering Ecology (CBS News). CBS. 2010-04-30. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ "Transocean Deepwater Horizon specifications". Transocean. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- ^ http://www.marketwatch.com/story/transocean-ltd-provides-deepwater-horizon-update-2010-04-26

- ^ http://www.offshore-technology.com/features/feature84446/

- ^ a b Tom Fowler (2010-04-21). "Workers missing after Transocean offshore rig accident". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ^ "BP confirms that Transocean Ltd issued the following statement today" (Press release). BP. April 21, 2010. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ^ "Deepwater Horizon Still on Fire in GOM". Rigzone. 2010-04-21. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ^ "Gibbs: Deepwater Horizon Aftermath Could Affect Next Lease Sale". Rigzone. 2010-04-30. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ a b "Macondo Prospect, Gulf of Mexico, USA". offshore-technology.com. 2005-10-20. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ "Deepwater Horizon Is On fire". gCaptain. 2010-04-20. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- ^ Wise, Lindsay; Latson, Jennifer; Patel, Purva (2010-04-22). "Rig blast survivor: 'We had like zero time'". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- ^ "Rig fire at Deepwater Horizon 4/21/10". CNN iReport. CNN. 2010-04-22. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ Jessica Resnick-Ault; Katarzyna Klimasinska (2010-04-22). "Transocean Oil-Drilling Rig Sinks in Gulf of Mexico". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Oil slick spreads from sunken rig (video interview)". CNN. 2010-04-22. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- ^ "100430-G-3080T-001-DHS News Conferencemov". Visual Information Gallery. United States Coast Guard. 2010-05-01. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g "At least 11 missing after blast on oil rig in Gulf". CNN. 2010-04-21. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ^ "At least 11 workers missing after La. oil rig explosion". USA Today. 2010-04-21. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ^ a b c d Noah Brenner, Anthony Guegel, Tan Hwee Hwee, Anthea Pitt (2010-04-22). "Coast Guard confirms Horizon sinks". Upstream Online. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Upstreamonline.com, April 30, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Nitrogen-Cement Mix Is Focus of Gulf Inquiry", The New York Times, May 10, 2010

- ^ a b Jordans, Frank (2010-04-30). "Rig had history of spills, fires before big 1". Associated Press. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Bubble of methane triggered rig blast – AP, May 7, 2010". News.yahoo.com. 2010-05-01. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ^ a b Chris Kirkham (2010-04-22). "Rescued oil rig explosion workers arrive to meet families at Kenner hotel". New Orleans Metro Real-Time News. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- ^ "Deepwater Horizon Is On fire; Officials Say Burning Oil Rig in Gulf of Mexico Has Sunk". ABC. 2010-04-22. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- ^ "Oil rig survivors back on land; 11 missing". Shreveport Times. 2010-04-22. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- ^ a b c Kaufman, Leslie (April 23, 2010). "Search Ends for Missing Oil Rig Workers". Retrieved April 24, 2010.

- ^ a b "Search for Missing Workers After La. Oil Rig Blast". Fox News. 2010-04-21. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ^ BP Probe: Methane Bubble Triggered Rig Blast. Youtube.com. 2010-04-30. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ^ Robertson, Campbell; Robbins, Liz (2010-04-21). "Workers Missing After Oil Rig Blast". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

- ^ "Transocean Ltd. Reports Fire on Semisubmersible Drilling Rig Deepwater Horizon" (Press release). Transocean. April 21, 2010. Retrieved April 21, 2010. Cite error: The named reference "coast guard rescue operation" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Coast guard calls off search for oil rig workers". CBC. 2010-04-23. Retrieved 2010-04-23.

- ^ Kevin McGill (2010-04-22). "11 missing in oil rig blast may not have escaped". Associated Press. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Template:Cite article Site includes publicly available obituaries that have been published about the 11 Deepwater Horizon crew members who were lost

- ^ Salazar Launches Safety and Environmental Protection Reforms to Toughen Oversight of Offshore Oil and Gas Operations, US department of Interior, May 11, 2010, retrieved 2010-05-13

- ^ Bart Stupak, Chairman (2010-05-12), Opening Statement, "Inquiry into the Deepwater Horizon Gulf Coast Oil Spill" (PDF), U.S. House Committee on Commerce and Energy, Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, retrieved 2010-05-12

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Template:Cite articleMemo

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ "Accident Investigation Report" (PDF). Minerals Management Service. 2008-05-26. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- ^ a b Fowler, Tom (2010-05-18). "BP Prepared for Top Kill to Plug Well". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ a b Burdeau, Cain (2010-04-30). "Document: BP didn't plan for major oil spill". Associated Press. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Juliet Eilperin (2010-05-05). "U.S. exempted BP's Gulf of Mexico drilling from environmental impact study". The Washington Post. The Washington Post Company. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ^ "RPT-BP's US Gulf project exempted from enviro analysis". Reuters.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ^ a b c Gold, Russell (2010-04-28). "Leaking Oil Well Lacked Safeguard Device". wsj.com. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

BP says the Deepwater Horizon did have a "dead man" switch, which should have automatically closed the valve on the seabed in the event of a loss of power or communication from the rig. BP said it can't explain why it didn't shut off the well.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ By MIKE SORAGHAN of Greenwire (2010-05-04). "Warnings on Backup Systems for Oil Rigs Sounded 10 Years Ago". NYTimes.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ^ "Coast Guard: Oil rig that exploded has sunk". CNN. 2010-04-22. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ Nichols, Bruce (2010-04-22). "Rig sinks in Gulf of Mexico, oil spill risk looms". Reuters. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jonsson, Patrik (2010-04-22). "Ecological risk grows as Deepwater Horizon oil rig sinks in Gulf". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ Nichols, Bruce (2010-04-23). "Oil spill not growing, search for 11 continues". Reuters. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ Jervis, Rick (2010-04-23). "Coast Guard: No oil leaking from sunken rig". USA Today. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ McGill, Kevin (2010-04-23). "Oil drilling accidents prompting new safety rules". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)[dead link] - ^ Coast Guard: Oil Not Leaking from Sunken Rig. CBS News. CBS. 2010-04-23. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ RAW: Interview with Rear Adm. Mary Landry. Clip Syndicate. WDSU NBC. 2010-04-23. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ a b c d "Oil rig wreck leaks into Gulf of Mexico". CBC News. Associated Press. 2010-04-25. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ "untitled". Associated Press. 2010-04-28. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ a b c d "US military joins Gulf of Mexico oil spill effort". BBC News. BBC. April 29, 2010. Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- ^ Griffitt, Michelle. "Initial Exploration Plan Mississippi Canyon Block 252 OCS-G 32306" (PDF). BP Exploration and Production. New Orleans, Louisiana: Minerals Management Service.

- ^ BP Permit for Thunder Horse Development (further clarifies units)

- ^ OnEarth.org, April 29, 2010; The Wall Street Journal, April 30, 2010.

- ^ Julie Cart (2010-05-01). "Tiny group has big impact on spill estimates". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "BP takes desperate measures as oil slick reaches US coast". The Sunday Times. Times Newspapers Ltd. May 2, 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Gulf Spill May Far Exceed Official Estimates". NPR. May 14, 2010. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ^ National Public Radio, May 14, 2010; The Guardian, May 14, 2010.

- ^ Obama denounces 'big oil blame game' as experts question information on leak by Jacqui Goddard. The Times, May 15, 2010

- ^ "Anderson Cooper 360: Gulf Oil Spill « – CNN.com Blogs". Ac360.blogs.cnn.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ^ http://today.msnbc.msn.com/

- ^ Gulf oil spill leak now pegged at 95,000 barrels a day (McClatchy Newspapers, May 19, 2000)

- ^ http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE6430AR20100521

- ^ http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/37257629/ns/gulf_oil_spill/?GT1=43001

- ^ a b c Staff writer (2010-04-25). "Robot subs trying to stop Gulf oil leak". CBC News. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ a b c "Gulf Oil Spill, by the Numbers". CBS News. 2010-04-30. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ News, CBC (May 2, 2010). "Gulf oil leak presents 'grave scenario'". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ McGreal, Chris (April 29, 2010). "Deepwater Horizon oil slick to hit US coast within hours". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Associated Press, MSNBC (April 30, 2010). "Oil from massive Gulf spill reaching La. coast". Mouth of the Mississippi River, Louisiana: msnbc.com. Associated Press. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Burdeau, Cain (14 May 2010). "Where's the oil? Much has evaporated". AP.

- ^ "Tracking the Oil Spill – An Interactive Map". nyt.com. May 1, 2010. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ MSNBC News http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/3032619#37140231 2m07s

- ^ http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/37248587/ns/us_news-the_new_york_times/page/2/

- ^ Henderson, Bruce; Price, Jay (2010-05-06). "Could oil leak reach N.C.? Unlikely, yet possible". The Charlotte Observer. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

- ^ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/05/100519112721.htm

- ^ "NOAA Observations Indicate a Small Portion of Light Oil Sheen Has Entered the Loop Current". Deepwater Horizon Incident Joint Information Center. 2010-05-19. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- ^ Heavy oil hits Louisiana shore

- ^ U.S. to check BP spill size, heavy oil comes ashore (Reuters, May 20, 2010)

- ^ Estimated rate of oil spill no longer holds up

- ^ Markey to Get Live Feed of BP Oil Spill on Website, by The House Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming, Press Release, 19-05-2010

- ^ BP switches on live video from oil leak, by Suzanne Goldberg, guardian.co.uk, 21-05-2010

- ^ http://www.cbsnews.com/video/watch/?id=6496749n Coast Guard Under 'BP's Rules'

- ^ "Growing concerns over Gulf of Mexico oil leak". BBC News. BBC. April 28, 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ The Observer, May 16, 2010. "Reactivating the BOP in this way could take 10 days and there's no guarantee it will work."

- ^ "US oil spill 'threatens way of life', governor warns". BBC News. BBC. May 2, 2010. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ Richard Fausset (2010-05-05). L.A. Times Blogs http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/greenspace/2010/05/gulf-oil-spill-smallest-leak-sealed-off-.html. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Winning, David (2010-05-03). "US Oil Spill Response Team: Plan To Deploy Dome In 6–8 Days". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company. (subscription required). Retrieved 2010-05-05.

{{cite news}}: More than one of|work=and|newspaper=specified (help) - ^ a b c Bolstad, Erika; Clark, Lesley; Chang, Daniel (2010-05-14). "Engineers work to place siphon tube at oil spill site". Toronto Star. McClatchy Newspapers. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

- ^ a b c d "'Top hat' dome at Gulf of Mexico oil spill site – BP". BBC News. 12-05-2010. Retrieved 2010-05-14.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b Collins, Jeffrey; Dearen, Jason (2010-05-16). "BP: Mile-long tube sucking oil away from Gulf well". News & Observer. Associated Press. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ^ Dittrick, Paula (2010-05-21). "BP captures varying rates in gulf oil spill response". Oil & Gas Journal. PennWell Corporation. (subscription required). Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ "AP Top News at 10:50 a.m. EDT". Associated Press. 2010-05-17. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ^ "Update on Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill Response - 24 May" (Press release). BP. 2010-05-24. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Bluestein, Greg (2010-04-25). "BP engineers draw up plans for 'top kill'". Associated Press. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ "Relief wells and Subsea containment illustration". BP.

- ^ "Heat on White House to do more about Gulf spill". Associated Press. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ^ "Second Macondo relief well under way". Upstream Online. 2010-05-17. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ BP press release, April 29, 2010; BP press release, April 30, 2010; Upstreamonline.com, April 30, 2010.

- ^ Tom Bergin (2010-04-30). "BP CEO says will pay oil spill claims". Reuters. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ The Washington Post, May 4, 2010. "Last week BP and the Coast Guard did that in what they described as a test; they burned 100 barrels of oil, a tiny fraction of what’s pouring from the well. They said later burns could consume as much as 1,000 barrels of oil, still less than the 5,000 barrels a day that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates is leaking into the gulf." See also reports by the New York Times, April 28, 2010, the Houston Chronicle, April 29, 2010 and BBC News, April 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Dittrick, Paula (2010-04-30). "Federal officials visit oil spill area, talk with BP". Oil and Gas Journal. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ Office of the Press Secretary (30 April 2010). "Statement by the President on the Economy and the Oil Spill in the Gulf of Mexico". The White House. The White House. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ Tapper, Jake (May 24, 2010). "Today's Qs for O's WH - 5/24/10". ABC News. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ Craig, Tiffany (May 24, 2010). "Is U.S. interior secretary confident BP knows what it's doing? 'No, not completely'". KENS 5-TV. Belo Corp. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ BP press release, April 29, 2010.

- ^ BP press release, April 30, 2010; The Washington Post, May 4, 2010.

- ^ AP wire story, May 2, 2010.

- ^ "BP Hopes to Contain Main Oil Leak in Gulf Soon". Voice of America. 2010-05-04. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ^ Four oil-cleanup workers fall ill; Breton Sound fleet ordered back to dock, by Times-Picayune Staff, NOLA.com, 26-05-2010

- ^ Seth Borenstein Oil spill is the 'bad one' experts feared April 30, 2010

- ^ Schleifstein, Mark. Plaquemines Parish President Nungesser claims berm oil capture plan killed. The Times Picayune. 22 May 2010.

- ^ Achenbach, Joel (May 23, 2010). "Gulf coast oil slick headed for Grand Isle, Louisiana". WashingtonPost.

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ . Agence France-Presse. 2010-05-01 http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5hew_8EkXXu79vuYRZ96WrFWDzQOw. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ What are oil dispersants? By the CNN Wire Staff May 15, 2010

- ^ Rebecca Renner US oil spill testing ground for dispersants Royal Society of Chemistry 07 May 2010

- ^ "Louisiana Officials, Attorney Want More Information From BP Concerning Spill". BayouBuzz. 08-05-2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Some oil spill events from Friday, May 14, 2010". The Sun News. Associated Press. 2010-05-14. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ^ a b c d Mark Guarino (2010-05-15). "In Gulf oil spill, how helpful – or damaging – are dispersants?". Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ http://www.propublica.org/ion/blog/item/In-Gulf-Spill-BP-Using-Dispersants-Banned-in-UK

- ^ a b c Mark Guarino (2010-05-17). "Gulf oil spill: Has BP 'turned corner' with siphon success?". Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Juliet Eilperin (2010-05-20). "Post Carbon: EPA demands less-toxic dispersant". Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Elisabeth Rosenthal (2010-05-24). "In Standoff With Environmental Officials, BP Stays With an Oil Spill Dispersant". New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ Douglas J. Suttles (2010-05-20). "EPA Release of BP's Response to Directive on Dispersants" (PDF). BP. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ Lisa P. Jackson (2010-05-24). "Statement by EPA Administrator Lisa P. Jackson from Press Conference on Dispersant Use in the Gulf of Mexico with U.S. Coast Guard Rear Admiral Landry" (PDF). Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ "Deepwater Horizon Incident, Gulf of Mexico". NOAA. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ US says BP move to curb oil leak 'no solution'

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ The Observer, May 2, 2010.

- ^ Henderson, Bruce (2010-05=22). "Oil may harm sea life in N.C." The Charlotte Observer. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ CNN wire story, April 29, 2010.

- ^ a b "Bryan Walsh. (2010-05-01). Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill: No End in Sight for Eco-Disaster. Time. Retrieved 2010-05-01". News.yahoo.com. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ Heavy oil hits Louisiana shore, enters sea current

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ BBC News, April 30, 2010.

- ^ "NOAA Closes Commercial and Recreational Fishing in Oil-Affected Portion of Gulf of Mexico". Deepwater Horizon Incident Joint Information Center. May 2, 2010. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ "NOAA Expands Commercial and Recreational Fishing Closure in Oil-Affected Portion of Gulf of Mexico". Deepwater Horizon Incident Joint Information Center. May 7, 2010. Retrieved May 8, 2010.

- ^ "NOAA shutting down 19 percent of Gulf fishing due to oil spill". Associated Press. May 18, 2010. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- ^ "FB10-040: BP Oil Spill: NOAA Modifies Commercial and Recreational Fishing Closure in the Oil-Affected Portions of the Gulf of Mexico" (PDF). NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Southeast Regional Office, Southeast Fishery Bulletin. May 18, 2010. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "FB10-045: BP Oil Spill: NOAA Modifies Commercial and Recreational Fishing Closure in the Oil-Affected Portions of the Gulf of Mexico" (PDF). NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Southeast Regional Office, Southeast Fishery Bulletin. May 25, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Jones, Steve (2010-05-22). "Wholesale seafood prices rising as oil spill grows". The Sun News. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ "In Precautionary Move, DHH Closes Additional Oyster Harvesting Areas West of the Mississippi Due to Oil Spill". State of Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. 2010-05-23. Retrieved 2010-05-24. Includes Map: Oyster Harvest Areas, 2010 Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill, May 23, 2010

- ^ a b c d Pagnamenta, Robin (2010-05-26). "Lloyd's syndicates launch legal action over BP insurance claim". The Times. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

- ^ AP wire story, May 14, 2010.

- ^ "Factbox—Companies Involved in US Gulf rig accident". 2010-04-30.

- ^ "Federal law may limit BP liability in oil spill". Associated Press. 2010-05-03. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ^ "Spill triggers effort to up liability cap".

- ^ "BP faces extra $60bn in legal costs as US loses patience with Gulf clean-up".

- ^ "Deepwater Horizon Oil Drilling Rig Explosion Lawsuits Filed by Two Families". aboutlawsuits.com. 2010-04-23. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ a b "BP, Transocean Lawsuits Surge as Oil Spill Spreads in Gulf". Bloomberg. 2010-05-01. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ a b Mufson, Steven; Eilperin, Juliet (2010-05-17). "Lawyers lining up for class-action suits over oil spill". The Washington Post. The Washington Post Company. p. A1. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ Buchanan, Susan (2010-05-24). "Fishermen grow wary as lawyers swarm after spill". Louisiana Weekly. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ^ Nicholas Johnston; Hans Nichols (2010-05-01). "Obama Orders Review, Says New Oil Leases Must Have Safeguards". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Globe and Mail, April 30, 2010.

- ^ The Globe and Mail, May 5, 2010.

- ^ Daniel B. Wood (2010-05-04). "Citing BP oil spill, Schwarzenegger drops offshore drilling plan". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

- ^ Rajesh Mirchandani (2010-05-03). "California's Schwarzenegger turns against oil drilling". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-05-06.

- ^ "Deepwater Horizon Accident Foreshadows a Potential Disaster Waiting to Happen in the Gulf". Commondreams.org. 2010-05-02.

- ^ Raúl M. Grijalva (2010-05-02). "Grijalva Calls For Investigation of Oil Drilling Safety Records as Whistleblower Suggests BP Is Operating Illegally". U.S. House of Representatives.

- ^ Guy Chazan and Ben Casselman (2010-04-28). "Documents Show BP Opposed New, Stricter Safety Rules". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Michael Kunzelmann (2010-05-06). "Oil spill: BP had no 'blowout' plan". Associated Press.

- ^ Weekly Address: President Obama Establishes Bipartisan National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling (White House Office of the Press Secretary, May 22, 2010)

- ^ Executive Order-- National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling (White House, May 22, 2010)

References

- News articles

- Johnson, Tim (2010-05-24). "Gulf recovered from last big oil spill, but is this one different?". miamiherald.com. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- Brenner, Noah; Guegel, Anthony; Pitt, Anthea (2010-04-30). "Congress calls Halliburton on Macondo". Upstreamonline.com. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- Broder, John M.; Robertson, Campbell; Krauss, Clifford (2010-05-05). "Amount of spill could escalate, company admits". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- Clanton, Brett; Tresaugue, Matthew; Hatcher, Monica (2010-04-29). "Coast Guard sets fire to the spreading slick as the threat to Louisiana grows". Houston Chronicle. pp. A1, A6. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- Faulkner, Katherine (2010-05-14). "Our oil spill is just tiny, says BP chief". Daily Mail. p. 21. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- Gertz, Emily (2010-04-29). "Gulf oil spill far worse than officials, BP admit, says independent analyst". OnEarth. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- Gillis, Justin (2010-05-18). "Giant Plumes of Oil Forming Under the Gulf". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- Goldenberg, Suzanne (2010-05-14). "Scientists study ocean footage to gauge full scale of oil leak". The Guardian. p. 29. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- Harris, Richard (2010-05-14). "Gulf spill may far exceed official estimates". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- Inskeep, Steve (2010-05-03). "BP will pay for Gulf oil spill disaster, CEO says". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- Kaufman, Leslie (2010-04-28). "'Controlled burn' considered for Gulf oil spill". The New York Times. pp. A1, A14. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- Mufson, Steven (2010-05-04). "Today's spills, yesterday's tools". The Washington Post. pp. A1, A8. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- Owen, Jonathan (2010-05-16). "BP boss defends company against Obama's attack". The Independent. p. 12. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- Pilkington, Ed; McKie, Robin. "Obama flies in to meet BP chief over Deepwater oil crisis". The Observer. pp. 1, 2. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

{{cite news}}: Text "date – 2010-05-02" ignored (help) - Pelley, Scott. "Blowout The Deepwater Horizon Disaster". CBS "60 Minutes". pp. 1–6. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

{{cite news}}: Text "date – 2010-05-16" ignored (help) - Robertson, Grant; Galloway, Gloria (2010-05-05). "Ottawa talks tough on offshore drilling". The Globe and Mail. pp. A1, A13. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- Shapiro, Joseph (2010-05-06). "Rig survivors felt coerced to sign waivers". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- Sherwell, Philip (2010-05-02). "Waiting for the black tide". The Sunday Telegraph. p. 25. Retrieved 2010-05-18.