Iranian architecture

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Iran |

|---|

|

|

|

Architecture is one of the fields in which Iranians have had a lengthy involvement in history. The major building types of this architecture are the mosque and the palace. The architecture makes use of abundant symbolic geometry, using pure forms such as the circle and square. Plans are based on often symmetrical layouts featuring rectangular courtyards and halls.

The post-Islamic architecture of Iran draws ideas from its pre-Islamic predecessor, and has geometrical and repetiitve forms, as well as surfaces that are richly decorated with glazed tiles, carved stucco, patterned brickwork, floral motifs, and calligraphy.

Overall, the architecture of the Iranian lands throughout the ages can be categorized into the following classes or styles ("sabk") [1]:

- Pre-Islamic:

- The "Parsi" style. Examples: Pasargad, Persepolis, Chogha zanbil, Sialk.

- The "Parthian" style. Examples: Anahita Temple, the vault of Kasra in Ctesiphon, and Bishapur.

- Post-Islamic:

- The "Khorasani" style. Examples: Mosque of Nain [2], Tarikhaneh-ye Damghan [3], Congregation (Jame) mosque of Isfahan [4].

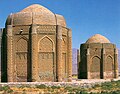

- The "Razi" style. Examples: Tomb of Isma'il of Samanid [5], Gonbad-e Qabus, Kharaqan towers.

- The "Azari" style. Examples: Soltaniyeh, Arg-i Alishah, Mosque of Varamin, Goharshad Mosque, Bibi Khanum mosque in Samarqand, Congregation mosque of Yazd.

- The "Isfahani" style. Examples: Chehelsotoon, Agha bozorg mosque in Kashan, Shah Mosque, Sheikh Lotf Allah Mosque.

Pre-Islamic Architecture of Persia (Iran)

By evidence, the history of architecture and urban planning in Iran (Persia) dates back some 10 thousand years ago. Persians were among the first to use mathematics, geometry, and astronomy in architecture. Teppe Sialk, an important ziggurat near Kashan, built 7000 years ago, represents one such prehistoric site in Persia whose inhabitants were the initiators of a simple and rudimentary housing technique.

Persian (Iranian) architecture left a profound influence on the architecture of old civilizations. Professor Arthur Pope wrote: "Architecture in Iran has at least 6,000 years of continuous history, examples of which can be seen from Syria to north India and Chinese borders, and from Caucasus to Zanzibar."

Iran ranks among the top 10 nations with the most architectural ruins from antiquity and is recognized by UNESCO as being one of the cradles of civilization.

Each of the periods of Elamites, Achaemenids, Parthians, and Sassanids were creators of great architecture that over the ages has spread wide and far to other cultures being adopted. Although Iran has suffered its share of destruction, including Alexander The Great's decision to burn Persepolis, there are sufficient remains to form a picture of its classical architecture.

The Achaemenids built on a grand scale. The artists and materials they used were brought in from practically all territories of what was then the largest state oin the world. Pasargadae set the standard: its city was laid out in an extensive park with bridges, gardens, colonnaded palaces and open column pavilions. Pasargadae along with Susa and Persepolis forcefully expressed the authority of The King of Kings, the staircases of the latter recording in relief sculpture the vast extent of the imperial frontier.

With the emergence of the Parthians and Sassanids there was an appearance of new forms. Parthian innovations fully flowered during the Sassanid period with massive barrel-vaulted chambers, solid masonry domes, and tall columns. This influence was to remain for years to come.

The roundness of the city of Baghdad in the Abbasid era for example, points to its Persian precedents such as Firouzabad in Fars.1 The two designers who were hired by al-Mansur to plan the city's design were Naubakht, a former Persian Zoroastrian who also determined that the date of the foundation of the city would be astrologically auspicious, and Mashallah, a former Jew from Khorasan.2

The ruins of Persepolis, Ctesiphon, Jiroft, Sialk, Pasargadae, Firouzabad, Arg-é Bam, and thousands of other ruins documented in only what is today Iran may give us merely a distant glimpse of what contribution Persians made to the art of building.

Post-Islamic Architecture of Persia (Iran)

Built during the Safavid period, an excellent example of Islamic Architecture in Persia (Iran). The fall of the Persian empire to invading Islamic forces ironically led to the creation of remarkable religious buildings in Iran. Arts such as calligraphy, stucco work, mirror work, and mosaic work, became closely tied with architecture in Iran in the new era. Archaeological excavations have provided sufficient documents in support of the impacts of Sasanian architecture on the architecture of the Islamic world.

Many experts believe the period of Persian architecture from the 15th through 17th Centuries to be the most brilliant of the post-Islamic era. Various structures such as mosques, mausoleums, bazaars, bridges, and different palaces have mainly survived from this period. In the old Persian architecture, semi-circular and oval-shaped vaults were of great interest, leading Safavi architects to display their extraordinary skills in making massive domes. Yet while the architecture of Ottoman Turks was philosophically intended to illustrate grandeur in scale, that of rival Safavi Isfahan had a smaller but refined elegence to it. It was the craftsmen of this school in Isfahan that ended up building their ultimate masterpiece, the Taj Mahal of India.

Domes can be seen frequently in the structurae of bazaars and mosques, particularly during the Safavi period in Isfahan. Iranian domes are distinguished for their height, proportion of elements, beauty of form, and roundness of the dome stem. The outer surfaces of the domes are mostly mosaic faced, and create a magical view.

According to Dr. D. Huff, a German archaeologist, the dome is the dominant element in Persian architecture. Professor Arthur U. Pope, who carried out extensive studies in ancient Persian and Islamic buildings, believed: "The supreme Iranian art, in the proper meaning of the word, has always been its architecture. The supremacy of architecture applies to both pre-and post-Islamic periods."

An investigation into post-Islamic architecture in Persia reveals how architecture was in harmony with the people, their environment, and their Creator. Yet no strict rules were applied to govern Islamic architecture. The great mosques of Khorasan, Isfahan, and Tabriz each used local geometry, local materials, and local building methods to express in their own ways the order, harmony, and unity of Islamic architecture. When the major monuments of Islamic Persian architecture are examined, they reveal complex geometrical relationships, a studied hierarchy of form and ornament, and great depths of symbolic meaning.

-

Architecture of Domes and Mosques. Tomb of Shah Nematollah Vali, built in the early 1300s in Mahan, Kerman, shows many of the characteristics of Persian architecture, including a geometrically tiled dome.

-

Architecture of Persian Gardens. Khalvat-i Karim-khani, in the gardens of the Golestan Palace.

-

Architecture of shrines and monuments. Shrine of Omar Khayam, Nishapur.

-

Craftsmanship in Architecture. An excellent animation depicting the excellent details of the interiors: (click)

-

Architecture of Palaces. Pasargad and Persepolis.

UNESCO designated World Heritage Sites

The following is a list of World Heritage Sites designed or constructed by Iranians (Persians), or designed and constructed in the style of Iranian architecture:

- Inside Iran:

- Arg-é Bam Cultural Landscape, Kerman

- Naghsh-i Jahan Square, Isfahan

- Pasargadae, Fars

- Persepolis, Fars

- Tchogha Zanbil, Khuzestan

- Takht-e Soleyman, West Azerbaijan

- Dome of Soltaniyeh, Zanjan

- Outside Iran:

- Taj Mahal, India - designed by the Mughal Empire

- Minaret of Jam, Afghanistan

- Tomb of Humayun, India

- Mausoleum of Khoja Ahmed Yasavi, Kazakhstan

- Historic Centre of Bukhara

- Historic Centre of Shahrisabz

- Samarkand - Crossroads of Cultures

- Citadel, Ancient City and Fortress Buildings of Darband, Daghestan

Iranian architects

See main article: List of historical Iranian architects.

Persian architects were a highly sought after stock in the old days, before the advent of Modern Architecture. Many, such as Ostad Isa Shirazi designed global landmarks such as The Taj Mahal, Afghanistan's Minaret of Jam, The Sultaniyeh Dome, or Tamerlane's tomb in Samarkand.

List of Iranian architecture related topics

- Persian gardens

- Sassanid architecture

- Architecture of cities: Kashan, Qazvin, Yazd, Isfahan, Shiraz, Qom, Mashad

- Caravanserais and Robats

- Windcatchers

- Shabestan

- Traditional Persian residential architcture

- Khaneqah and Tekyeh

- Towers

- Traditional water sources of Persian antiquity

- Islamic architecture

- Mughal architecture

- Indian architecture

- Imamzadeh

- Args, Castles, and Ghal'ehs

References

- Islam Art and Architecture. Markus Hattstein, Peter Delius. 2000. p96. ISBN 3-8290-2558-0

- Islamic Science and Engineering. Donald R. Hill. 1994. p10. ISBN 0-748-60457-X

- Sabk Shenasi Mi'mari Irani (Study of styles in Iranian architecture), M. Karim Pirnia. 2005. ISBN 964-96113-2-0

- FROM ARISTOTLE TO ZOROASTER : AN A TO Z COMPANION TO THE CLASSICAL WORLD, A. Cotterell, ISBN 0684855968, 1998.

See also

- Architecture

- Islamic architecture

- Mughal architecture

- Modern architecture

- Indian architecture

- Cultural Heritage Organization of Iran

External links

- Memaran, a Persian language online Architecture magazine

- Watch "Isfahan the Movie" on QuickTime Player to see superb example of Isfahan architecture.

- Excellent article by Nima Kasraie about Persian Architecture, with 59 photos from Kashan.