American Civil War

| American Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(clockwise from upper right) Confederate prisoners at Gettysburg; Battle of Fort Hindman, Arkansas; Rosecrans at Stones River, Tennessee | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

United States of America File:Us flag large 35 stars.png |

Confederate States of America File:3rdnational.png | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Abraham Lincoln Ulysses S. Grant |

Jefferson Davis Robert E. Lee | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,556,678 | 1,064,200 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

KIA: 110,100 Total dead: 359,500 Wounded: 275,200 |

KIA: 74,500 Total dead: 198,500 Wounded: 137,000+ | ||||||

The American Civil War (1861–1865) was a civil war between the United States of America, called the Union, and the Confederate States of America, formed by eleven Southern states that had seceded[1] from the Union. The Union won a decisive victory, followed by a period of Reconstruction. The war produced more than 970,000 casualties (3 percent of population), including approximately 560,000 deaths. The causes of the war, the reasons for the outcome, and even the name of the war itself, are subjects of much controversy, even today.

Historiography: Multiple explanations of why War began

- Main articles: Origins of the American Civil War, Timeline of events

The origin of the American Civil War lay in the complex issues of slavery, politics, disagreements over the scope of States' rights versus federal power, expansionism, sectionalism, economics, modernization, and competing nationalism of the Antebellum period. Although there is little disagreement among historians on the details of the events that led to war, there is disagreement on exactly what caused what and the relative importance. There is no consensus on whether the war could have been avoided, or if it should have been avoided.

Failure to compromise

In 1854 the old political system broke down after passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The Whig Party disappeared, and the new Republican Party arose in its place. It was the nation's first major political party with only sectional appeal; though it had much of the old Whig economic platform, its popularity rested on its commitment to stop the expansion of slavery into new territories. Open warfare in the Kansas Territory, the panic of 1857, and John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry further heightened sectional tensions and helped Republicans sweep elections in 1860. In 1860, the election of Abraham Lincoln, who met staunch opposition from Southern slave-owning interests, triggered Southern secession from the union. The new president decided to resort to arms, if necessary, to preserve the nation's territorial integrity.

Historians in the 1930s such as James G. Randall argued that the rise of mass democracy, the breakdown of the old two-party system, and increasingly virulent and hostile sectional rhetoric made it highly unlikely, if not impossible, to bring about the compromises of the past (such as the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850) necessary to avoid crisis. Although numerous compromises were proposed, none were successful in reuniting the country. One possible "compromise" was peaceful secession agreed to by the United States, which was seriously discussed in late 1860—and supported by many abolitionists—but was rejected by both Buchanan's conservative Democrats and the Republican leadership.

Southern nationalism: Psychological nationhood

Most historians agree, following Ulrich B. Phillips, Avery Craven, and Eugene Genovese that the South had grown apart from the North psychologically and in terms of its value systems. One by one the common elements that bound the nation together were broken. For example the major Protestant denominations split along North-South lines. Fewer travelers or students or businessmen went from one region to the other. The last common elements were the Constitution (which was in dispute after the Dred Scott ruling of 1857); the political parties (which split along regional lines in 1860), and Congress, which was in constant turmoil after 1856.

Slavery as a cause of the War

Focus on the slavery issue has been cyclical. It was considered the main cause in the 1860–1890 era. From 1900 to 1960, historians considered anti-slavery agitation to be less important than constitutional, economic, and cultural issues. Since the 1960s historians have returned to an emphasis on slavery as a major cause of the war. Specifically, they note that the South insisted on protecting it and the North insisted on weakening it. A small but militant abolitionist movement existed in the North--a matter of a few thousand advocates. Their insistence that slavery was a sin and slave owners were deeply guilty angered the South. Historians have looked at many slave owners and decided that they felt neither guilt nor shame, but were angry at what they considered unchristian hate speech from abolitionists. By the 1830s there was a widespread ideological defense of the "peculiar institution" everywhere in the South.

As territorial expansion forced the nation to confront the question of whether new territories were to become "slave" or "free," and as multiplying free states became a majority in the Union, the Slave Power in national politics waned.

Economics

The North and South did have different economies but they were complementary and not in competition. The South made money by exporting cotton (and other unique crops like tobacco). The North made money by exporting food and manufactured items. Many northern business interests were closely tied to the Southern economy and pleaded for union and compromise. Some Southerners thought they paid too much in tariffs--but they themselves had written and voted for the tariff laws in effect.

The cotton-growing export business or "King Cotton," as it was touted, was so important to the world economy, southerners argued, that they could stand alone. Indeed, being tied to the North was a hindrance and an economic burden. The South would do better by trading directly with Europe and avoiding extortionate Yankee middlemen.

Ideologies

In the view of many northern Republicans, the Slave Power ruled the South, not democracy. This "Slave Power" was a small group of very wealthy slave owners, especially cotton planters, who dominated the politics and society of the South. However, historians more recently have emphasized that the South was much more democratic than the Republicans of North believed. Both North and South believed strongly to republican values of democracy and civic virtue. But their conceptualizations were diverging. Each side though the other was aggressive, and was violating both the Constitution and the core values of American republicanism. Nationalism was the dominant force in Europe in the 19th century and likewise in America. The South was much more explicit in defining nationalism as a regional characteristic. The North paid less attention to nationalism before 1860, but then focused its mind on it and stressed the whole country, North and South, was the unit of nationalism.

This economic differentiation had social and political consequences beyond the issue of slavery itself; for instance, Pennsylvania politicians pushed for a protective tariff to help the iron industry, while the cotton-exporting South wanted to keep the existing policy of nearly free trade.

At a deeper level industrialization in the Northeast and farming in the Midwest depended on free labor, which could not exist alongside slave labor, as Lincoln kept emphasizing. The nation had to be all free or all slave, said Lincoln. (Historians Charles and Mary Beard went so far as to argue in 1928 that this sectional conflict was a "Second American Revolution"—a revolutionary watershed in the rise of modern industrial society in the United States.)

States Rights

The States' rights debate cut across the issues. Southern politicians argued that the federal government had no power to prevent slaves from being carried into new territories, but they also demanded federal jurisdiction over slaves who escaped into the North; Northern politicians took reversed, though equally contradictory, stances on these issues.

Slavery in the Territories

The specific political crisis that culminated in secession and civil war stemmed from a dispute over the expansion of slavery into new territories. The reason was that Congress had power over slavery in the territories, but not in the states. With new territories being formed--especially Kansas--the issue of slaver had to be confronted. This argument grew out of the acquisition of vast new lands during the Mexican War (1846–48). Free-state politicians such as David Wilmot, who personally had no sympathy for abolitionism, feared that slaves would provide too much competition for free labor, and thus effectively keep free-state migrants out of newly opened territories. Slaveholders felt that any ban on slaves in the territories was a discrimination against their peculiar form of property, and would undercut both the financial value of slaves and the institution itself. (Slaves comprised the second most valuable form of property in the South, after real estate.) In Congress, the end of the Mexican War was overshadowed by a fight over the Wilmot Proviso, a provision that Wilmot tried (and failed) to enact to bar slavery from all lands acquired in the conflict.

The dispute led to open warfare after the Kansas Territory was organized in the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. This act repealed the prohibition on slavery there under the Missouri Compromise of 1820, and put the fate of slavery in the hands of the territory's settlers, a process known as "popular sovereignty." Proslavery Missourians expected that Kansas, due west of their state, would naturally become a slave state, and were alarmed by an organized migration of antislavery New Englanders. Soon heavily armed "border ruffians" from Missouri battled antislavery forces under John Brown, among other leaders. Hundreds were killed or wounded. Southern congressmen, perceiving a Northern conspiracy to keep slavery out of Kansas, insisted that it be admitted as a slave state. Northerners, pointing to the large and growing majority of antislavery voters there, denounced this effort. By 1860, sectional divisions had grown deep and bitter.

16th President (1861–1865)

Southern fears of Modernity

Southern secession was triggered by the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln because it was feared that he would make good on his promise to stop the expansion of slavery and put it on a course toward extinction. If not Lincoln, then sooner or later another Yankee, many Southerners said; it was time to quit the Union. The slave states had lost the balance of power in the Electoral College and the Senate, and were facing a future as a perpetual minority. In a broader sense the North was rapidly modernizing its economy and its world view; slavery had no role in modern America. Historian James McPherson (1983 p 283) explains:

When secessionists protested in 1861 that they were acting to preserve traditional rights and values, they were correct. They fought to preserve their constitutional liberties against the perceived Northern threat to overthrow them. The South's concept of republicanism had not changed in three-quarters of a century; the North's had. ... The ascension to power of the Republican Party, with its ideology of competitive, egalitarian free-labor capitalism, was a signal to the South that the Northern majority had turned irrevocably towards this frightening, revolutionary future.

— James McPherson, "Antebellum Southern Exceptionalism: A New Look at an Old Question," Civil War History 29 (Sept. 1983)

Secession

Before Lincoln took office, seven states seceded from the Union, and established an independent Southern government, the Confederate States of America on February 9, 1861. They took control of federal forts and property within their boundaries, with little resistance from President Buchanan. By seceding, the rebel states gave up any claim to the Western territories that were in dispute, canceled any obligation for the North to return fugitive slaves to the Confederacy, and assured easy passage in Congress of many bills and amendments they had long opposed.

The Civil War began when, under orders from Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard opened fire upon Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, on April 12, 1861. There were no casualties from enemy fire in this battle.

Division of the country

The Union States

There were 23 Union States: California, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Wisconsin. The Union counted Virginia as well, and added Nevada and West Virginia. It added Tennessee, Louisiana, and other rebel states as soon as they were reconquered.

The territories of Colorado, Dakota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Washington also fought on the Union side. There was a civil war inside the Oklahoma territory.

The Confederacy

Seven states seceded by March 1861:

- South Carolina (December 21 1860),

- Mississippi (January 9 1861),

- Florida (January 10 1861),

- Alabama (January 11 1861),

- Georgia (January 19 1861),

- Louisiana (January 26 1861),

- Texas (February 1 1861).

These states of the Deep South, where slavery and cotton were most dominant, formed the Confederate States of America (February 4 1861), with Jefferson Davis as president, and a governmental structure closely modeled on the U.S. Constitution (see also: Confederate States Constitution).

After the surrender of Fort Sumter, April 13, 1861, Lincoln called for troops from all states to put down the insurrection, resulting in the secession of four more states:

- Virginia (April 17 1861),

- Arkansas (May 6 1861),

- North Carolina (May 20 1861), and

- Tennessee (June 8 1861).

Border states

Main article: Border states (Civil War)

Along with the northwestern portion of Virginia (whose residents did not wish to secede and eventually entered the Union in 1863 as West Virginia), four of the five northernmost "slave states" (Maryland, Delaware, Missouri, and Kentucky) did not secede, and became known as the Border States. There was considerable anti-war or "Copperhead" sentiment in the southern parts of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, and some men volunteered for Confederate service; however much larger numbers, led by John A. Logan, joined the Union army.

Maryland had numerous pro-Confederate officials, but after rioting in Baltimore and other events had prompted a Federal declaration of martial law, Union troops moved in, and arrested the pro-Confederates. Both Missouri and Kentucky remained in the Union, but factions within each state organized governments in exile that were recognized by the CSA.

In Missouri, an elected convention on secession voted decisively to remain within the Union. However, pro-Southern Governor Claiborne F. Jackson called out the state militia, which was attacked in St. Louis by federal forces under General Nathaniel Lyon, who chased the governor and the rest of the State Guard to the southwestern corner of the state. (See also: Missouri secession).

Although Kentucky did not secede, for a time it declared itself neutral. During a brief invasion by Confederate forces, Southern sympathizers organized a secession convention, inaugurated a Confederate Governor, and gained recognition from the Confederacy. However, the military occupation of Columbus by Confederate General Leonidas Polk in September 1861 turned general popular opinion in Kentucky against the Confederacy, and the state subsequently reaffirmed its loyal status and expelled the Confederate government.

Residents of the northwestern counties of Virginia organized a secession from Virginia and entered the Union in 1863 as West Virginia. Similar secessions were supported in some other areas of the Confederacy (such as eastern Tennessee), but were suppressed by declarations of martial law by the Confederacy.

Narrative summary: 1861 to Fort Sumter

Lincoln's victory in the presidential election of 1860 triggered South Carolina's secession from the Union. By February 1, 1861, six more Southern states had seceded. On February 7, the seven states adopted a provisional constitution for the Confederate States of America and established their capital at Montgomery, Alabama. The pre-war February peace conference of 1861 met in Washington, as one last attempt to avoid war; it failed. The remaining southern states as yet remained in the Union. Confederate forces seized all but three federal forts within their boundaries (they did not take Fort Sumter); President Buchanan made no military response, but governors in Massachusetts, New York and Pennsylvania began secretly buying weapons and training militia units to ready them for immediate action.

On March 4, 1861, Abraham Lincoln was sworn in. In his inaugural address, he argued that the Constitution was a more perfect union than the earlier Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union, that it was a binding contract, and called the secession "legally void". He stated he had no intent to invade southern states, but would use force to maintain possession of federal property. His speech closed with a plea for restoration of the bonds of union. The South did send delegations to Washington and offered to pay for the federal properties, but they were turned down. Lincoln refused to negotiate with any Confederate agents because he insisted the Confederacy was not a legitimate government.

On April 12, Confederate soldiers fired upon the Federal troops stationed at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, until the troops surrendered. Lincoln called for all of the states in the Union to send troops to recapture the forts and preserve the Union. Most Northerners hoped that a quick victory for the Union would crush the nascent rebellion, and so Lincoln only called for volunteers for 90 days. Four states, Tennessee, Arkansas, North Carolina, and—most importantly, Virginia—which had repeatedly rejected Confederate overtures now decided that they could not send forces against the seceding states. They seceded and to reward Virginia the Confederate capital was moved to Richmond, Virginia, a highly vulnerable location at the end of the supply line.

Even though the Southern states had seceded, there was considerable anti-secessionist sentiment within several of the seceding states. Eastern Tennessee, in particular, was a hotbed for pro-Unionism. Winston County, Alabama issued a resolution of secession from the state of Alabama. The Red Strings were a prominent Southern anti-secession group.

Winfield Scott created the Anaconda Plan to win the war with as little bloodshed as possible. His idea was that a Union blockade would strangle the rebel economy, then capture of the Mississippi would split the South. Lincoln adopted the plan but overruled Scott's warnings against an immediate attack on Richmond.

Naval war and blockade

Union blockade and Confederate States Navy

In May 1861 Lincoln proclaimed the Union blockade of all southern ports, which shut down nearly all international traffic and most local port-to-port traffic. Although few naval battles were fought and few men were killed, the blockade shut down King Cotton and ruined the southern economy. British investors built small, very fast "blockade runners" that brought in military supplies (and civilian luxuries) from Cuba and the Bahamas and took out some cotton and tobacco. When the blockade captured one the ship and cargo were sold and the proceeds given to the Union sailors. The crews were British, so when they were captured they were released and not held as prisoners of war. The most famous naval battle was the Battle of Hampton Roads (often called "the Battle of the Monitor and the Merrimac") in March 1862, in which Confederate efforts to break the blockade were frustrated. Other naval battles included Island No. 10, Memphis, Drewry's Bluff, Arkansas Post, and Mobile Bay.

Eastern Theater 1861–1863

Because of the fierce resistance of a few initial Confederate forces at Manassas, Virginia, in July 1861, a march by Union troops under the command of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell on the Confederate forces there was halted in the First Battle of Bull Run, or First Manassas, whereupon they were forced back to Washington, D.C., by Confederate troops under the command of Generals Joseph E. Johnston and P.G.T. Beauregard. It was in this battle that Confederate General Thomas Jackson received the name of "Stonewall" because he stood like a stone wall against Union troops. Alarmed at the loss, and in an attempt to prevent more slave states from leaving the Union, the U.S. Congress passed the Crittenden-Johnson Resolution on July 25 of that year, which stated that the war was being fought to preserve the Union and not to end slavery.

Major General George B. McClellan took command of the Union Army of the Potomac on July 26 (he was briefly general-in-chief of all the Union armies, but was subsequently relieved of that post in favor of Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck), and the war began in earnest in 1862.

Upon the strong urging of President Lincoln to begin offensive operations, McClellan invaded Virginia in the spring of 1862 by way of the peninsula between the York River and James River, southeast of Richmond. Although McClellan's army reached the gates of Richmond in the Peninsula Campaign, Joseph E. Johnston halted his advance at the Battle of Seven Pines, then Robert E. Lee defeated him in the Seven Days Battles and forced his retreat. McClellan was stripped of many of his troops to reinforce John Pope's Union Army of Virginia. Pope was beaten spectacularly by Lee in the Northern Virginia Campaign and the Second Battle of Bull Run in August.

Emboldened by Second Bull Run, the Confederacy made its first invasion of the North, when General Lee led 55,000 men of the Army of Northern Virginia across the Potomac River into Maryland on September 5. Lincoln then restored Pope's troops to McClellan. McClellan and Lee fought at the Battle of Antietam near Sharpsburg, Maryland, on September 17 1862, the bloodiest single day in American history. Lee's army, checked at last, returned to Virginia before McClellan could destroy it. Antietam is considered a Union victory because it halted Lee's invasion of the North and provided justification for Lincoln to announce his Emancipation Proclamation.

When the cautious McClellan failed to follow up on Antietam, he was replaced by Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside. Burnside suffered near-immediate defeat at the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13 1862, when over ten thousand Union soldiers were killed or wounded. After the battle, Burnside was replaced by Maj. Gen. Joseph "Fighting Joe" Hooker. Hooker, too, proved unable to defeat Lee's army; despite outnumbering the Confederates by more than two to one, he was humiliated in the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863. He was replaced by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade during Lee's second invasion of the North, in June. Meade defeated Lee at the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863), the largest battle in North American history, which is sometimes considered the war's turning point. Lee's army suffered 28,000 casualties (versus Meade's 23,000), again forcing it to retreat to Virginia, never to launch a full-scale invasion of the North again. Lincoln was angry that Meade failed to intercept Lee's retreat, and decided to turn to the Western Theater for new leadership.

On the use of balloons, see Aerial warfare section on the American Civil War.

Western Theater 1861–1863

While the Confederate forces had numerous successes in the Eastern theater, they crucially failed in the West. They were driven from Missouri early in the war as result of the Battle of Pea Ridge. Leonidas Polk's invasion of Kentucky enraged the citizens there who previously had declared neutrality in the war, turning that state against the Confederacy.

Nashville, Tennessee, fell to the Union early in 1862. Most of the Mississippi was opened with the taking of Island No. 10 and New Madrid, Missouri, and then Memphis, Tennessee. New Orleans, Louisiana, was captured in May 1862, allowing the Union forces to begin moving up the Mississippi as well. Only the fortress city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, prevented unchallenged Union control of the entire river.

Braxton Bragg's second Confederate invasion of Kentucky was repulsed by Don Carlos Buell at the confused and bloody Battle of Perryville and he was narrowly defeated by William S. Rosecrans at the Battle of Stones River in Tennessee.

The one clear Confederate victory in the West was the Battle of Chickamauga in Georgia, near the Tennessee border, where Bragg, reinforced by the corps of James Longstreet (from Lee's army in the east), defeated Rosecrans, despite the heroic defensive stand of George Henry Thomas, and forced him to retreat to Chattanooga, which Bragg then besieged.

The Union's key strategist and tactician in the west was Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who won victories at: Forts Henry and Donelson, by which the Union seized control of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers; Shiloh; the Battle of Vicksburg, cementing Union control of the Mississippi River and considered one of the turning points of the war; and the Battle of Chattanooga, Tennessee, driving Confederate forces out of Tennessee and opening an invasion route to Atlanta and the heart of the Confederacy.

Trans-Mississippi Theater 1861–1865

Though geographically isolated from the battles to the east, a number of small-scale military actions took place west of the Mississippi River. Confederate incursions into Arizona and New Mexico were repulsed in 1862. Guerilla activity turned much of Missouri and Indian Territory (Oklahoma) into a battleground. Late in the war the Federal Red River Campaign was a failure. Texas remained in Confederate hands throughout the war, but was cut off after the capture of Vicksburg in 1863 gave the Union control of the Mississippi River.

End of the War 1864–1865

At the beginning of 1864, Lincoln made Grant commander of all Union armies. Grant made his headquarters with the Army of the Potomac, and put Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman in command of most of the western armies. Grant understood the concept of total war and believed, along with Lincoln and Sherman, that only the utter defeat of Confederate forces and their economic base would bring an end to the war. He devised a coordinated strategy that would strike at the heart of Confederacy from multiple directions: Generals Grant, Meade, and Benjamin Butler would move against Lee near Richmond; General Franz Sigel (and later Philip Sheridan) would invade the Shenandoah Valley; General Sherman would and capture Atlanta and march to the sea; Generals George Crook and William W. Averell would operate against railroad supply lines in West Virginia; and General Nathaniel Banks would capture Mobile, Alabama.

Union forces in the East attempted to maneuver past Lee and fought several battles during that phase ("Grant's Overland Campaign") of the Eastern campaign. An attempt to outflank Lee from the south failed under Butler, who was trapped inside the Bermuda Hundred river bend. Grant was tenacious and, despite astonishing losses (over 66,000 casualties in six weeks), kept pressing Lee's Army of Northern Virginia back to Richmond. He pinned down the Confederate army in the Siege of Petersburg, where the two armies engaged in trench warfare for over nine months.

Grant finally found a commander, General Philip Sheridan, aggressive enough to prevail in the Valley Campaigns of 1864. Sheridan proved to be more than a match for Jubal Early, and defeated him in a series of battles, including a final decisive defeat at Cedar Creek, Sheridan then proceeded to destroy the agricultural base of the Valley, a strategy similar to the tactics Sherman would later employ in Georgia.

Meanwhile, Sherman marched from Chattanooga to Atlanta, defeating Confederate Generals Joseph E. Johnston and John B. Hood. The fall of Atlanta, on September 2, 1864, was a significant factor in the re-election of Abraham Lincoln, as President of the Union. Leaving Atlanta, and his base of supplies, Sherman's army marched with an unclear destination, laying waste to about 20% of the farms in Georgia in his celebrated "March to the Sea", and reaching the Atlantic Ocean at Savannah, Georgia in December 1864. Burning plantations as they went, Sherman's army was followed by thousands of freed slaves. When Sherman turned north through South Carolina and North Carolina to approach the Virginia lines from the south, it was the end for Lee and his men, and for the Confederacy.

Lee attempted to escape from the besieged Petersburg and link up with Johnston in North Carolina, but he was overtaken by Grant. He surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House. Johnston surrendered his troops to Sherman shortly thereafter at a local family's farmhouse in Durham, North Carolina. The Battle of Palmito Ranch, fought on May 13, 1865, in the far south of Texas, was the last Civil War land battle and ended, ironically, with a Confederate victory. All Confederate land forces surrendered by June 1865.

Analysis of the outcome

Why the Union prevailed (or why the Confederacy was defeated) in the Civil War has been a subject of extensive analysis and debate.

Could the South have won? A significant number of scholars believe that the Union held an insurmountable advantage over the Confederacy in terms of industrial strength, population, and the determination to win. Confederate actions, they argue, could only delay defeat. Southern historian Shelby Foote expressed this view succinctly in Ken Burns's television series on the Civil War: "I think that the North fought that war with one hand behind its back.... If there had been more Southern victories, and a lot more, the North simply would have brought that other hand out from behind its back. I don't think the South ever had a chance to win that War." [Ward 1990 p 272]

Other historians, however, suggest that the South had a chance to win its independence. As James McPherson has observed, the Confederacy remained on the defensive, which required fewer military resources. The Union, committed to the strategic offensive, faced enormous manpower demands that it often had difficulty meeting. War weariness among Union civilians mounted along with casualties, in the long years before Union advantages proved decisive. Thus, the inevitability of Union victory remains hotly contested among scholars.

The goals were not symmetric. To win independence the South had to convince the North it could not win, but it did not have to invade the North. To restore the Union the North had to conquer vast stretches of territory. In the short run (a matter of months) the two sides were evenly matched. But in the long run (a matter of years) the North had advantages that increasingly came into play.

Both sides had long-term advantages but the Union had more of them. The Union had to control the entire coastline, defeat all the main Confederate armies, seize Richmond, and control most of the population centers. As the occupying force they had to station hundreds of thousands of soldiers to control railroads, supply lines, and major towns and cites. The long-term advantages widely credited by historians to have contributed to the Union's success include:

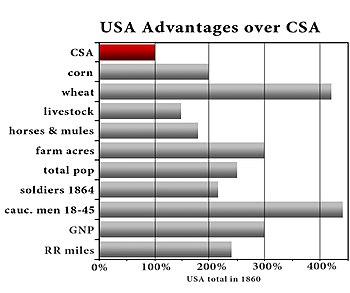

- The more industrialized economy of the North, which aided in the production of arms, munitions and supplies, as well as finances, and transportation. The graph shows the relative advantage of the USA over the CSA.

- A party system that enabled the Republicans to mobilize soldiers and support at the grass roots, even when the war became unpopular. The Confederacy deliberately did not use parties.

- The Union population was 22 million and the South 9 million in 1861; the disparity grew as the Union controlled more and more southern territory with garrisons, and cut off the trans-Mississippi part of the Confederacy.

- Excellent railroad links between Union cities, which allowed for the quick and cheap movement of troops and supplies. Transportation was much slower and more difficult in the South which was unable to augment its much smaller system or repair damage, or even perform routine maintenance.

- The Union devoted much more of its resources to medical needs, thereby overcoming the unhealthy disease environment that sickened (and killed) more soldiers than combat did.

- The Union at the start controlled over 80% of the shipyards, steamships, river boats, and the Navy. It augmented these by a massive shipbuilding program. This enabled the Union to control the river systems and to blockade the entire southern coastline.

- The Union's more established government, particularly a mature executive branch which accumulated even greater power during wartime, may have resulted in less regional infighting and a more streamlined conduct of the war. Failure of Davis to maintain positive and productive relationships with state governors damaged the Confederate president's ability to draw on regional resources.

- The Confederacy's tactic of engaging in major battles at the cost of heavy manpower losses, when it could not easily replace its losses.

- The Confederacy's failure to fully use its advantages in guerrilla warfare against Union communication and transportation infrastructure. However, as Lee warned, such warfare would prove devastating to the South, and (with the exception of Confederate partisans in Missouri) Confederate leaders shrank from it.

- Despite the Union's many tactical blunders like the Seven Days Battle, those commited by Confederate generals, such as Lee's miscalculations at the Battle of Gettysburg and Battle of Antietam, were far more serious—if for no other reason than that the Confederates could so little afford the losses.

- Lincoln proved more adept than Davis in replacing unsuccessful generals with better ones.

- Strategically the location of the capital Richmond tied Lee to a highly exposed position at the end of supply lines. (Loss of Richmond, everyone realized, meant loss of the war.)

- Lincoln grew as a grand strategist, in contrast to Davis. The Confederacy never developed an overall strategy. It never had a plan to deal with the blockade. Davis failed to respond in a coordinated fashion to serious threats, such as Grant's campaign against Vicksburg in 1863 (in the face of which, he allowed Lee to invade Pennsylvania).

- The Confederacy's failure to win diplomatic or military support from any foreign powers. Its King Cotton misperception of the world economy led to bad diplomacy, such as the refusal to ship cotton before the blockade started.

- Most important, the Union had the will to win, and leaders like Lincoln, Seward, Stanton, Grant, and Sherman would do whatever it took to achieve victory. The Confederacy, as Beringer et al (1986) argue, may have lacked the total commitment needed to win. It took time, however, for leaders such as Grant, Sherman, and Sheridan to emerge; in the meantime, Union public opinion wavered, and Lincoln worried about losing the election of 1864, until victories in the Shenandoah Valley and Atlanta made victory seem likely.

Major land battles

There were as many as 10,000 hostile engagements during the war. The costliest and most significant are listed in Battles of the American Civil War.

Civil War leaders and soldiers

One of the reasons that the U.S. Civil War wore on as long as it did and the battles were so fierce was that most important generals on both sides had formerly served in the United States Army—some, including Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, during the Mexican-American War between 1846 and 1848. Most were graduates of the United States Military Academy at West Point. Southern military commanders and strategists included Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee, Joseph E. Johnston, Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson, James Longstreet, P.G.T. Beauregard, John Mosby, Braxton Bragg, John Bell Hood, James Ewell Brown (JEB) Stuart, William Mahone, Judah P. Benjamin, Jubal Early, and Nathan Bedford Forrest.

Northern military commanders and strategists included Abraham Lincoln, Edwin M. Stanton, Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, George H. Thomas, George B. McClellan, Henry W. Halleck, Joseph Hooker, Ambrose Burnside, Irvin McDowell, Winfield Scott, Philip Sheridan, George Crook, George Armstrong Custer, George G. Meade, and Winfield Hancock

After 1980, scholarly attention turned to ordinary soldiers, and to women and African Americans involved with the War. As James McPherson observed "The profound irony of the Civil War was that Confederate and Union soldiers ... interpreted the heritage of 1776 in opposite ways. Confederates fought for liberty and independence from what they regarded as a tyrannical government; Unionists fought to preserve the nation created by the founders from dismemberment and destruction."(McPherson 1994 p 24)

The Question of Slavery

Given the painfulness of the historical memory of slavery for many Americans, its role in the war remains controversial to this day. To understand its place in the conflict, it is necessary to divide the issue in two: slavery as a motivation for secession, and abolition as a Union war aim.

In the weeks and months preceding the secession of the Confederate states, Southern leaders spoke openly about their desire to preserve slavery, and their fears for the "peculiar institution" if the South remained within the Union. Almost all of the ordinances of secession cited the preservation of slavery as a primary, even the foremost, reason for departure from the Union. And yet many individual Southern soldiers fought for reasons quite apart from the defense of slavery: to protect their families and communities, to defend their home states, and out of a nascent sense of nationality.

On the Union side, Lincoln initially declared his purpose in prosecuting the war to be the preservation of the Union, not emancipation. He had no wish to alienate the thousands of slaveholders in the Union border states. The long war, however, had a radicalizing effect on federal policies. With the Emancipation Proclamation, announced in September 1862 and put into effect four months later, Lincoln adopted the abolition of the Slave Power as a second mission—that is slaves owned by rebels had to be taken away from them and freed. One goal was to destroy the economic basis of the Confederate leadership class, and another goal was to actually liberate the 4 million slaves, which was accomplished by 1865.

The Emancipation Proclamation declared all slaves held in territory then under Confederate control to be "then, thenceforth, and forever free," but did not affect slaves in areas under Union control. It did, however, show the Union that slavery's days were numbered, increasing abolitionist support in the North. The border states (except Kentucky) abolished slavery on their own.

Foreign diplomacy

Because of the Confederacy's attempt to create a new state, recognition and support from the European powers were critical to its prospects. The Union, under Secretary of State William Henry Seward attempted to block the Confederacy's efforts in this sphere. The Confederates hoped that the importance of the cotton trade to Europe (the idea of cotton diplomacy) and shortages caused by the war, along with early military victories, would enable them to gather increasing European support and force a turn away from neutrality.

President Lincoln's decision to announce a blockade of the Confederacy, a clear act of war, enabled Britain, followed by other European powers, to announce their neutrality in the dispute. This enabled the Confederacy to begin to attempt to gain support and funds in Europe. President Jefferson Davis had picked Robert Toombs of Georgia as his first Secretary of State. Toombs, having little knowledge in foreign affairs, was replaced several months later by Robert M. T. Hunter of Virginia, another choice with little suitability. Ultimately, on March 17, 1862, Davis selected Judah P. Benjamin of Louisiana as Secretary of State, who although having more international knowledge and legal experience with international slavery disputes still failed in the end to create a dynamic foreign policy for the Confederacy.

The first attempts to achieve European recognition of the Confederacy were dispatched on February 25, 1861 and led by William Lowndes Yancey, Pierre A. Rost, and Ambrose Dudley Mann. The British foreign minister Lord John Russell met with them, and the French foreign minister Edouard Thouvenel received the group unofficially. However, at this point, the two countries had agreed to coordinate and cooperate and would not make any rash moves.

Charles Francis Adams proved particularly adept as ambassador to Britain for the Union, and Britain was reluctant to boldly challenge the Union's blockade. The Confederacy also attempted to initiate propaganda in Europe through journalists Henry Hotze and Edwin De Leon in Paris and London. However, public opinion against slavery created a political liability for European politicians, especially in Britain. A significant challenge in Anglo-Union relations was also created by the Trent Affair, involving the Union boarding of a British mail steamer to seize James M. Mason and John Slidell, Confederate diplomats sent to Europe. However, the Union was able to smooth over the problem to some degree.

As the war continued, in late 1862, the British considered initiating an attempt to mediate the conflict. However, the Union victory in the Battle of Antietam caused them to delay this decision. Additionally, the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation further reinforced the political liability of supporting the Confederacy. As the war continued, the Confederacy's chances with Britain grew more hopeless, and they focused increasingly on France. Napoléon III proposed to offer mediation in January 1863, but this was dismissed by Seward. Despite some sympathy for the Confederacy, France's own concerns in Mexico ultimately deterred them from substantially antagonizing the Union. As the Confederacy's situation grew more and more tenuous and their pleas increasingly ignored, President Davis sent Duncan F. Kenner to Europe, in November 1864, to test whether a promised Confederate emancipation of its slaves could lead to possible recognition. The proposal was strictly rejected by both Britain and France.

Aftermath

Northern leaders agreed that the war would be over when Confederate nationalism was dead, and slavery was dead. They disagreed sharply on how to identify these goals. They also disagreed on the degree of federal control that should be imposed on the South. The fighting ended with the surrender of all the Confederate forces. There was no significant guerrilla warfare. Many senior Confederate leaders escaped to Europe, but Davis was captured and imprisoned, but never brought to trial. The question became how much the Union could trust the ex-Confederates to be truly loyal to the United States. The second main question in Reconstruction dealt with the destruction of slavery. The XIII Amendment (1865) officially abolished it legally, but the issue was whether black codes indicated a sort of semi-slavery, and whether Freedmen should have the vote to protect those rights. In 1867 Radicals in Congress pushed aside President Johnson and imposed new rules. Freedmen gained the right to vote and formed Republican political coalitions that took control of each state for varying periods. One by one the white conservatives or "Redeemers" gained back control of their states, often through lethal force. The final three were redeemed by the Compromise of 1877. After that the hatreds between North and South rapidly diminished until by 1900 the nation was no longer divided by the war, though it did remain divided by race.

Ghosts of the conflict still persist in America. For decades after the war, Northern politicians "waved the bloody shirt," bringing up memories of the Civil War as an electoral tactic, while the "solid South" as a block in national politics was built on memories of the war and a determination to maintain segregation. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s had its neoabolitionist roots in the failure of Reconstruction. A few debates surrounding the legacy of the war continue, especially regarding memorials and celebrations of Confederate heroes and battle flags. The question is a deep and troubling one: Americans with Confederate ancestors cherish the memory of their bravery and determination, yet their cause remains one ultimately tied to the shameful history of African American slavery.

Further reading

Overviews

- Beringer, Richard E., Archer Jones, and Herman Hattaway, Why the South Lost the Civil War (1986) analysis of factors

- Catton, Bruce, The Civil War, American Heritage, 1960, ISBN 0-8281-0305-4, illustrated narrative

- Donald, David ed. Why the North Won the Civil War (1977) (ISBN: 0020316607), short interpretive essays

- Donald, David et al. The Civil War and Reconstruction (latest edition 2001); 700 page survey

- Eicher, David J., The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, Simon & Schuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Fellman, Michael et al. This Terible War: The Civil War and its Aftermath (2003), 400 page survey

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars (1959), these maps are online

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative (3 volumes), Random House, 1974, ISBN 0-394-74913-8. Highly detailed narrative covering all fronts

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (1988), survey; Pulitzer prize

- Mark E. Neely Jr.; "Was the Civil War a Total War?" Civil War History, Vol. 50, 2004 pp 434+ in JSTOR

- Nevins, Allan. Ordeal of the Union, an 8-volume set (1947-1971). the most detailed narrative

- 1. Fruits of Manifest Destiny, 1847-1852; 2. A House Dividing, 1852-1857; 3. Douglas, Buchanan, and Party Chaos, 1857-1859; 4. Prologue to Civil War, 1859-1861; 5. The Improvised War, 1861-1862; 6. War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863; 7. The Organized War, 1863-1864; 8. The Organized War to Victory, 1864-1865

- Rhodes, James Ford. History of the Civil War, 1861-1865 (1918), Pulitzer Prize; a short version of his 5-volume history

- Ward, Geoffrey C. The Civil War (Alfred Knopf, 1990), based on PBS series by Ken Burns; visual emphasis

- Weigley, Russell Frank. A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History, 1861-1865 (2004); primarily military

Reference books and bibliographies

- Blair, Jayne E. The Essential Civil War: A Handbook to the Battles, Armies, Navies And Commanders (2006)

- Carter, Alice E. and Richard Jensen. The Civil War on the Web: A Guide to the Very Best Sites- 2nd ed. (2003)

- Current, Richard N., et al eds. Encyclopedia of the Confederacy (1993) (4 Volume set; also 1 vol abridged version) (ISBN: 0132759918)

- Faust, Patricia L. (ed.) Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War (1986) (ISBN: 0061812617) 2000 short entries

- Eicher, David J., The Civil War in Books: An Analytical Bibliography, University of Illinois, 1997, ISBN 0-252-02273-4

- Heidler, David Stephen. Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History (2002), 1600 entries in 2700 pages in 5 vol or 1-vol editions

- Wagner, Margaret E. Gary W. Gallagher, and Paul Finkelman, eds. The Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference (2002)

- Woodworth, Steven E. ed. American Civil War: A Handbook of Literature and Research (1996) (ISBN: 0313290199), 750 pages of historiography and bibliography

Biographies

- Eicher, John H., & Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3

- Freeman, Douglas S., R. E. Lee, A Biography (4 volumes), Scribners, 1934

- Freeman, Douglas S., Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command (3 volumes), Scribners, 1946, ISBN 0-684-85979-3

- Smith, Jean Edward, Grant, Simon and Shuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84927-5

- Warner, Ezra J., Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders, Louisiana State University Press, 1964, ISBN 0-8071-0882-7

- Warner, Ezra J., Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders, Louisiana State University Press, 1959, ISBN 0-8071-0823-5

Soldiers

- Frank, Joseph Allan and George A. Reaves. Seeing the Elephant: Raw Recruits at the Battle of Shiloh (1989)

- Hess, Earl J. The Union Soldier in Battle: Enduring the Ordeal of Combat (1997)

- McPherson, James. What They Fought For, 1861-1865 (Louisiana State University Press, 1994)

- McPherson, James. For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War (1998)

- Wiley, Bell Irvin. The Life of Johnny Reb: The Common Soldier of the Confederacy (1962) (ISBN: 0807104752)

- Wiley, Bell Irvin. Life of Billy Yank: The Common Soldier of the Union (1952) (ISBN: 0807104760)

Primary sources

- U.S. War Dept., The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901. 70 very large volumes of letters and reports written by both armies. Online at [1]

- Bedwell, Randall, War is All Hell: A Collection of Civil War Quotations, Cumberland House Publishing, 1999, ISBN 1-58182-419-X

- Commager, Henry Steele (ed.). The Blue and the Gray. The Story of the Civil War as Told by Participants. (1950), often reprinted

- Eisenschiml, Otto; Ralph Newman; eds. The American Iliad: The Epic Story of the Civil War as Narrated by Eyewitnesses and Contemporaries (1947)

- Hesseltine, William B. ed.; The Tragic Conflict: The Civil War and Reconstruction (1962)

- Woodword, C. Vann, Ed., Mary Chesnut's Civil War, Yale University Press, 1981, ISBN 0-300-02979-9 Pulitzer Prize

Novels about the war

- Crane, Stephen, The Red Badge of Courage

- Doctorow, E.L., The March

- Frazier, Charles, Cold Mountain

- Mitchell, Margaret, Gone with the Wind

- Reed, Ishmael, Flight to Canada

- Shaara, Jeffrey, Gods and Generals

- Shaara, Jeffrey, The Last Full Measure

- Shaara, Michael, The Killer Angels

- Street, James, By Valour and Arms

- Verne, Jules, Texar's Revenge, or, North Against South (Nord Contre Sud)

- Vidal, Gore, Lincoln

Films about the war

- The Birth of a Nation (1915)

- Gone With the Wind (1939)

- The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

- The Blue and the Gray(1982)

- Glory (1989)

- Gettysburg (1993)

- Gods and Generals (2003)

- Cold Mountain (2003)

Documentaries about the war

- The Civil War, directed by Ken Burns

See also

- African Americans in the Civil War

- California and the Civil War

- Canada and the American Civil War

- Casualties of the American Civil War

- Illinois in the Civil War

- Military history of the Confederate States

- Military history of the United States

- National Civil War Museum

- Naming the American Civil War

- List of American Civil War topics

- List of people associated with the American Civil War

- Official Records of the American Civil War

- Origins of the American Civil War

- Photography and photographers of the American Civil War

- Rail transport in the American Civil War

- U.S. Congress Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War

- Union Army Balloon Corps

- Union blockade

External links

- The American Civil War Homepage

- Civil War photos at the National Archives

- Civil War in Virginia

- Civil War Research & Discussion Group - Fields Of Conflict - Containing 1500+ Links And 400+ Articles.

- Civil War Pictures Database

- Online texts of Civil War books at the National Park Service

- Religion and the American Civil War

- University of Tennessee: U.S. Civil War Generals

- Shotgun's Home of the American Civil War

- American Civil War

- American Civil War Detailed Chronology

- The Civil War, a PBS documentary by Ken Burns

- Individual state's contributions to the Civil War: California, Florida, Illinois #1, Illinois #2, Ohio, Pennsylvania

- State declarations of the causes of secession: Mississippi, Georgia, Texas, South Carolina

- Ordinances of Secession for all CSA states

- Alexander Hamilton Stephens' Cornerstone Speech

- Civil War Trails — A project to map out sites related to the Civil War in Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina

- Civil War Audio Resources

- Hoard Historical Museum in Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin

- The Handbook of Texas Online: Civil War

- The Brothers War

- Civil War Band Collection: 1st Brigade Band of Brodhead, Wisconsin A digital collection of first person narrative accounts from Wisconsin soldiers and citizens, documenting their wartime experiences.

- Wisconsin Goes to War: Our Civil War Experience

- "A Divided Nation". One of World Book Encyclopedia's monthly features, this one on the American Civil War.