Kerala

Kerala (IPA: ['kɛrʌɹlʌ]; Malayalam: കേരളം — Keralam) is a state on the tropical Malabar Coast of southwestern India. To its east and northeast, Kerala borders Tamil Nadu and Karnataka; to its west and south lie the Indian Ocean islands of Lakshadweep and the Maldives, respectively. Kerala also envelops Mahé, a coastal exclave of the Union Territory of Pondicherry. Kerala is one of five states that comprise the linguistic-cultural region known as South India.

In prehistory, Kerala's rainforests and wetlands — then thick with malaria-bearing mosquitoes and man-eating tigers — were largely avoided by Neolithic humans. Indeed, no evidence of habitation prior to around 1,000 BCE exists. Only then did tribes of megalith-building proto-Tamil speakers from northwestern India settle in Kerala. Subsequent contact with the Mauryan Empire spurred development of new Keralite polities — including the Cheran kingdom and feudal Namboothiri Brahminical city-states — and an indigenous Keralite culture, including kalarippayattu, kathakali, and Onam. More than a millennium of overseas contact and trade culminated in four centuries of struggle between and among multiple colonial powers and native Keralite states. This ended when the November 1, 1956 States Reorganisation Act elevated Kerala to statehood.

Radical social reforms begun in the 19th century by the kingdoms of Kochi and Travancore — and spurred by such leaders as Narayana Guru and Chattampi Swamikal — were continued by post-Independence governments, making Kerala among the Third World's longest-lived, healthiest, and most literate regions. Kerala's 3.18 crore (31.8 million) people now live under a stable democratic socialist political system and exhibit unusually equitable gender relations. However, Kerala's suicide, unemployment, and violent crime rates are among India's highest.

Accounts of the etymology underlying "Kerala" differ; according to the prevailing theory, it as an imperfect portmanteau that fuses kera ("coconut palm tree") and alam ("land" or "location"). Natives of Kerala — "Keralites" — thus refer to their land as Keralam. Another theory has the name originating from the phrase chera alam ("land of the Chera").

Geography

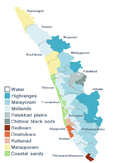

Kerala’s 38,863 km² (1.18% of India’s landmass) are wedged between the Arabian Sea to the west and the Western Ghats — identified as one of the world's twenty-five biodiversity hotspots[1] — to the east. Situated between north latitudes 8°18' and 12°48' and east longitudes 74°52' and 72°22',[2] Kerala lies well within the humid tropics, near the equator. Kerala’s coast runs some 580 km in length, while the state itself varies between 35–120 km in width. Geographically, Kerala roughly divides into three climatically distinct regions: the eastern highlands (rugged and cool mountainous terrain), the central midlands (rolling hills), and the western lowlands (coastal plains). Located at the extreme southern tip of the Indian subcontinent, Kerala lies near the center of the Indian tectonic plate; as such most of the state (notwithstanding isolated regions) is subject to comparatively little seismic or volcanic activity.[3] Geologically, pre-Cambrian and Pleistocene formations comprise the bulk of Kerala’s terrain.

Eastern Kerala lies immediately west of the Western Ghats's rain shadow; it consists of high mountains, gorges, and deep-cut valleys. Forty-one of Kerala’s westward-flowing rivers — as well as three of its eastward-flowing ones — originate in this region. Here, the Western Ghats form a wall of mountains interrupted only near Palakkad; here, a pass known as the Palakkad Gap breaks through to access the rest of India. The Western Ghats rises on average to 1,500 m elevation above sea level, while the highest peaks may reach to 2,500 m. Just west of the mountains lie the midland plains, comprising a swathe of land running along central Kerala. Here, rolling hills and valleys dominate.[2] Generally ranging between elevations of 250–1,000 m, the eastern portions of the Nilgiri and Palni Hills include such formations as Agastyamalai and Anamalai.

Kerala’s western coastal belt is relatively flat, and is crisscrossed by a network of interconnected brackish canals, lakes, estuaries, and rivers known as the Kerala Backwaters. Lake Vembanad — Kerala’s largest body of water — dominates the Backwaters; it lies between Alappuzha and Kochi and is over 200 km² in area. Indeed, around 8% of India's waterways (measured by length) are found in Kerala.[4] The most important of Kerala’s forty-four rivers include the Periyar (244 km in length), the Bharathapuzha (209 km), the Pamba (176 km), the Chaliyar (169 km), the Kadalundipuzha (130 km), and the Achankovil (128 km). Most of the remainder are small and entirely fed by monsoon rains.[2] These conditions result in the nearly year-round waterlogging of such western regions as Kuttanad, 500 km² of which lie below sea level.

| Agroecology of Kerala | |

| |

Kerala's climate is mainly wet and maritime tropical,[5] heavily influenced by the seasonal heavy rains brought by the Southwest Summer Monsoon. In eastern Kerala, a drier tropical wet and dry climate prevails. Kerala receives an average annual rainfall of 3,107 mm — some 70.3 km3 of water. This compares to the all-India average of 1,197 mm. Parts of Kerala's lowlands may average only 1,250 mm annually while the cool mountainous eastern highlands of Idukki district — comprising Kerala's wettest region — receive in excess of 5,000 mm of orographic precipitation (4,200 mm of which are available for human use) annually. Kerala's rains are mostly the result of seasonal monsoons. As a result, Kerala averages some 120–140 rainy days per year. In summers, most of Kerala is prone to gale-force winds, storm surges, and torrential downpours accompanying dangerous cyclones coming in off the Indian Ocean. It is also prone to occassional droughts,[6] as well as rises in sea level and cyclonic activity resulting from global warming.[7][8] Kerala’s average maximum daily temperature is around 36.7 °C; the minumum is 19.8 °C.[2] Mean annual temperatures range from between 25.0–27.5 °C in the coastal lowlands to between 20.0–22.5 °C in the highlands.[9]

Flora and fauna

Kerala harbours significant biodiversity,[10] most of which is concentrated in the east. Its 9,400 km² of forests include tropical wet evergreen and semi-evergreen forests (lower and middle elevations — 3,470 km²), tropical moist and dry deciduous forests (mid-elevations — 4,100 km² and 100 km², respectively), and montane subtropical and temperate (shola) forests (highest elevations — 100 km²). Altogether, 24% of Kerala is forested.[11] Two of the world’s Ramsar Convention-listed wetlands — Lake Sasthamkotta and the Vembanad-Kol wetlands — are also in Kerala, as well as 1455.4 km² of the vast Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. Subjected to extensive clearing for cultivation in the 20th century,[12] much of Kerala's forest cover is now protected from clearfelling.

Eastern Kerala’s windward mountains shelter tropical moist forests and tropical dry forests, which are common in the Western Ghats. Here, sonokeling (binomial nomenclature: Dalbergia latifolia — Indian rosewood), anjili (Artocarpus hirsuta), mullumurikku (Erthrina), and caussia number among the more than 1,000 species of trees in Kerala. Other flora includes bamboo, wild black pepper (Piper nigrum), wild cardamom, the calamus rattan palm (Calamus rotang — a type of giant grass), and aromatic vetiver grass (Vetiveria zizanioides).[11] Among them, such fauna as Asian Elephant (Elephas maximus), Bengal Tiger (Panthera tigris tigris), Leopard (Panthera pardus), Nilgiri Tahr (Nilgiritragus hylocrius), Common Palm Civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus), and Grizzled Giant Squirrel (Protoxerus stangeri).[11][13] Reptiles include the king cobra, viper, python, and crocodile. Kerala's birds are legion — Peafowl, the Great Hornbill (Buceros bicornis), Indian Grey Hornbill, Indian Cormorant, and Jungle Myna are several emblematic species. In lakes, wetlands, and waterways, fish such as kadu (stinging catfish — Heteropneustes fossilis)[14] and choottachi (orange chromide — Etroplus maculatus; valued as an aquarium specimen) can be found.[15]

History

Legend states that Kerala was created by an act of Parasurama, an avatar of Mahavishnu.[16][17] Meanwhile, historians note the 10th century BCE emergence of prehistoric pottery and granite burial monuments — which resemble their counterparts in Western Europe and the rest of Asia. These were produced by speakers of a proto-Tamil language.[16] Thus, Kerala and Tamil Nadu once shared a common language, ethnicity, and culture. This common area is known as Tamilakam. Later, Kerala became a linguistically separate region by the early 14th century. The ancient Chera empire, whose court language was Tamil, ruled Kerala from their capital at Vanchi and was the first major recorded kingdom. Allied with the Pallavas, they continually warred against the neighboring Chola and Pandya kingdoms. A Keralite identity, distinct from the Tamils and associated with the second Chera empire and the development of Malayalam, evolved during the 8th–14th centuries. In written records, Kerala was first mentioned in the Sanskrit epic Aitareya Aranyaka. Later, figures such as Katyayana, Patanjali, Pliny the Elder, and the unknown author of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea all displayed familiarity with Kerala.

In subsequent centuries, settlers from abroad established Kerala's Jewish community. Later arrivals included Muslim Arab merchants in the 8th century, while a disputed theory has Christianity arriving with Apostle Thomas in 52 CE. In 345 CE, Kerala’s Nasrani community was founded by Jewish Christian settlers under merchant Knai Thomman. More than 1,100 years later, Vasco da Gama’s 1498-05-20 arrival inaugurated a period of Portuguese colonial administration, with the goal of controlling a lucrative spice trade. While seeking to convert Nasranis to Roman Catholicism, they also established fortresses and settlements, thereby ending an Arab trade monopoly. Later conflicts between the cities of Kozhikode (Calicut) and Kochi (Cochin), however, provided an opportunity for the Dutch oust the Portuguese.

In turn, the Dutch were ousted at the 1741 Battle of Kulachal by Marthanda Varma of Thiruvithamcoore (Travancore), who received aid from the British. Meanwhile, Mysore’s Hyder Ali conquered northern Kerala, capturing Kozhikode in 1766. In the late 18th century, Tipu Sultan — Ali’s successor — launched campaigns against the growing British Raj; these resulted in two of the four Anglo-Mysore Wars. However, Tipu Sultan was ultimately forced to cede Malabar District and South Kanara, (including today’s Kasargod District) to the Raj in 1792 and 1799, respectively. The Raj then forged tributary alliances with Kochi (1791) and Travancore (1795). Meanwhile, Malabar and South Kanara became part of the Madras Presidency. Kerala saw little mass defiance against the Raj — nevertheless, several rebellions occurred, including the October 1946 Punnapra-Vayalar revolt.[18] Many mass actions instead protested such social mores as untouchability; these included the 1924 Vaikom Satyagraham. Due to this pressure, outcastes were allowed admittance to temples across Kerala.

After India's independence in 1947, Travancore and Kochi were merged to form the province of Travancore-Cochin on July 1, 1949 — on 1950-01-26 (the date India became a republic), Travancore-Cochin was recognized as a state. In the same time, the Madras Presidency became Madras State in 1947. Finally, the Government of India's 1956-11-01 States Reorganisation Act inaugurated a new state — Kerala — incorporating Malabar District, Travancore-Cochin, and the taluk of Kasargod, South Kanara.[19] A new Legislative Assembly was also created, for which elections were held in 1957. These resulted in a communist-led government[19] — one of the world's first[20] — headed by E.M.S. Namboodiripad. Subsequent radical reforms introduced by the Namboodiripad and subsequent governments favoured tenants and labourers[21][22] — this facilitated, among other things, improvements in living standards, education, and life expectancies.

Districts

| Districts of Kerala | |

| |

| Source: (Government of Kerala 2001). | |

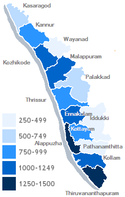

Kerala's fourteen districts are distributed among Kerala's three historical regions: Malabar, Kochi, and Travancore. Malabar (northern Kerala) includes (from north to south) Kasargod, Kannur (Cannanore), Wayanad (Wynad), Kozhikode (Calicut), Malappuram, and Palakkad (Palghat). Kochi (central Kerala) includes Thrissur (Trichur) and Ernakulam (Cochin) districts. Lastly, the Travancore region (southern Kerala) is composed of Idukki, Alappuzha (Alleppey), Kottayam, Pathanamthitta, Kollam (Quilon), and Thiruvananthapuram (Trivandrum).

Mahe, a part of the union territory of Pondicherry, is an enclave within Kerala. Thiruvananthapuram is the state capital. Kochi is the largest city and considered the commercial capital of the state. The city of Ernakulam (on Ernakulam district's coast) is the state's judicial capital.

Politics

Like other Indian states, Kerala is governed via a parliamentary system of representative democracy; universal suffrage is granted to residents. There are three branches of government. The legislature — the Legislative Assembly — is composed of elected members as well as special offices (the Speaker and Deputy Speaker) elected by assemblymen. In turn, Assembly meetings are presided over by the Speaker (or the Deputy Speaker, if the Speaker is absent). The judiciary is composed of an apex High Court of Kerala (including a Chief Justice combined with twenty-six permanent and two additional (pro tempore) justices) and a system of lower courts. Lastly, the executive authority — composed of the Governor of Kerala (the de jure head of state and appointed by the President of India), the Chief Minister of Kerala (the de facto head of state; the Legislative Assembly's majority party leader is appointed to this position by the Governor), and the Council of Ministers (appointed by the Governor, with input from the Chief Minister). In turn, the Council of Ministers answers to the Legislative Assembly. In addition, auxiliary authorities — panchayats, for which elections are regularly held — govern local affairs.

Kerala hosts two major political alliances: the United Democratic Front (UDF — led by the Indian National Congress) and the Left Democratic Front (LDF — led by the Communist Party of India (Marxist)). At present, the UDF is the ruling party and Oommen Chandy is the current Chief Minister. Nevertheless, Kerala numbers among India’s most left-wing states. Keralites, when compared to most other Indians, participate heavily in the political arena.

Economy

For the past several decades, Kerala's economy was mainly a welfare-based democratic socialist; nevertheless, the state is increasingly — along with the rest of India — liberalizing its economy, thus transitioning to a more mixed economy with a greater role played by the free market and foreign direct investment. In comparison to neighbouring states, Kerala has exhibited relatively little economic growth, and few major corporations and manufacturing plants choose to operate in Kerala.[23] This is mitigated by the remittances of overseas Keralites, which contributes around 20% of the state's gross domestic product.[24] Kerala's economic productivity and per capita GDP — 11,819 INR[25] — lags behind that of the rest of India. However, Kerala's Human Development Index and standard of living statistics are the nation's best.[26] This seeming paradox is often dubbed the "Kerala phenomenon" or the "Kerala model" of development,[27][28] and arises mainly from Kerala's unusually strong service sector.

Agriculture dominates Kerala's economy. Some six hundred varieties[1] of rice (Kerala's most important staple food and cereal crop[29]) are harvested from 310,521 ha (a decline from 588,340 ha in 1990[29]) of paddy fields; 688,859 tonnes are produced per annum.[30] Other key crops include coconut (899,198 ha), tea, coffee (23% of Indian production,[31] or 57,000 tonnes[32]), rubber, cashew, and spices — including pepper, cardamom, vanilla, cinnamon, and nutmeg. Home gardens and animal husbandry also provide work for hundreds of thousands of people. Tourism, manufacturing, and business process outsourcing comprise other significant economic sectors. Kerala's unemployment rate is 19.2%,[33] although underemployment of those classified as "employed" is a significant problem.[34][35] Estimates of the statewide poverty rate range from 12.72%[36] to as high as 36%,[37] while more than 45,000 Keralites live in slum conditions.[38]

Demographics

Virtually all of Kerala's 3.18 crore (31.8 million)[39] people are of Malayali Dravidian ethnicity. Other than Dravidians, thousands of Arabs, Jews, Portuguese, Dutch, and British have settled in Kerala. Kerala is also home to 321,000 indigenous tribal Adivasis (1.10% of the populace), who are mostly concentrated in the eastern districts.[40][41] Malayalam is Kerala's official language; Tamil and various Adivasi languages are also spoken by ethnic minorities. Kerala is home to 3.44% of India's people, and — at 819 persons per km²[42] — its land is three times as densely settled as the rest of India. However, Kerala's population growth rate is far lower than the national average. Whereas Kerala's population more than doubled between 1951 and 1991 — adding 156 lakh (15.6 million) people to reach a total of 291 lakh (29.1 million) residents in 1991 — the population stood at less than 320 lakh (32 million) by 2001. Kerala's people are most densely settled in the coastal region, leaving the eastern hills and mountains comparatively sparsely populated.[2] Women comprise 51.42% of the population,[43] while Kerala's principal religions are Hinduism (56.1%), Islam (24.7%), and Christianity (19%).[44] Remnants of a once substantial Cochin Jewish population — most of which made aliyah to Israel or emigrated to other First World nations — also practice Judaism. In comparison with the rest of India, Kerala experiences relatively little sectarianism. Nevertheless, there have been signs of increasing influences from religious extremist organisations.[45][46] In addition, Kerala has among the highest rates of criminality — including rates of rape and violent crime far above national averages[47] — in India, ranking third among Indian states.[43]

Kerala's society is less patriarchical than the rest of the Third World.[48][49] Many Keralites (especially the Nair caste and Muslims of Malabar) follow a traditional matrilineal system known as marumakkatayam. However, Christians, Muslims, and some Hindu castes such as the Namboothiri and Ezhava follow makkathayam, a patrilineal system.[50] Kerala's gender relations are among the most equitable in India and the Third World.[51] However, this too is coming under threat, this time from such forces as patriarchy-enforced effeminization of women (for example, 45% of Keralite women have experienced gender-based violence,[52] while domestic violence against women is rising[53]), globalisation, modernization, and "Sanskritisation" (the subaltern poor's emulation of higher castes).[49]

Kerala's human development indices — elimination of poverty, primary-level education, and healthcare — are among the best in India. For example, Kerala's literacy rate — 91%[54] — and life expectancy — 73 years[54] — are now the highest in India. This is the result of efforts begun before 1911 by Cochin and Travancore states to boost social welfare.[55][56] This focus was maintained by Kerala's post-independence government.[57][26][28] However, Kerala's unemployment and suicide rates are unusually high by Indian standards. Kerala's above-unity female-to-male ratio — 1.058 — also distinguishes it from the rest of India.[54][58] The same is true of its sub-replacement fertility level and infant mortality rate (estimated at 12[23][59] to 14[60] deaths per 1,000 live births). However, Kerala's morbidity rate is higher than that of any other Indian state — 118 (rural Keralites) and 88 (urban) per 1,000 people; the corresponding all-India figures are 55 and 54 per 1,000, respectively.[60] Kerala's 13.3% prevalence of low birth weight is substantially higher than that of First World nations.[59] Further, outbreaks of water-borne diseases — including diarrhea, dysentery, hepatitis, and typhoid[61] — among the more than 50% of Keralites who rely on some 30 lakh (3 million)[62] water wells[63] constitutes another problem, a situation only exacerbated by the widespread lack of sewerage.[63]

Kerala's healthcare system has garnered international acclaim, with UNICEF and the World Health Organization (WHO) designating Kerala the world's first "baby-friendly state" — for example, more than 95% of Keralite births are hospital-delivered.[59] Aside from ayurveda (both elite and popular forms),[64] siddha, and unani, many endangered and endemic modes of traditional medicine — including kalari, marmachikitsa,[65] and vishavaidyam — are practiced. These propagate via gurukula discipleship,[66] and comprise a fusion of both medicinal and supernatural treatments,[67] and are partly responsible for drawing increasing numbers of medical tourists. A steadily aging population — 11.2% of Keralites are over age 60[26] — and low birthrate[48] (18 per 1,000[59] — among the under-developed world's lowest) make Kerala (together with Cuba) one of the few regions of the Third World to have undergone the "demographic transition" characteristic of such developed nations as Canada, Japan, and Norway.[27]

Culture

Kerala's culture is mainly Dravidian in origin, deriving from a greater Tamil-heritage region known as Thamizhagom. Later, Kerala's culture was elaborated upon by centuries of contact with overseas lands.[68] Native performing arts include koodiyattom, kathakali (from katha ("story") and kali ("performance")) and its offshoot Kerala natanam, koothu (akin to stand-up comedy), mohiniaattam ("dance of the enchantress"), thullal, padayani, and theyyam. Other arts are more religion- and tribal-themed. These include oppana (originally from Malabar), which combines dance, rhythmic hand clapping, and ishal vocalizations. However, many of these artforms largely play to tourists or at youth festivals, and are not as popular among most ordinary Keralites. These people look to more contemporary art and performance styles, including those employing mimicry and parody. Additionally, a substantial Malayalam film industry effectively competes against both Bollywood and Hollywood.

Malayalam literature is ancient in origin, and includes such figures as the 14th century Niranam poets (Madhava Panikkar, Sankara Panikkar and Rama Panikkar), whose works mark the dawn of both modern Malayalam language and indigenous Keralite poetry. The "triumvirate of poets" (Kavithrayam: Kumaran Asan, Vallathol Narayana Menon, and Ulloor S. Parameswara Iyer) are recognized for moving Keralite poetry away from archaic sophistry and metaphysics and towards a more lyrical mode. In the second half of the nineteenth centuary, Jnanpith awardees like G Sankara Kurup, S. K. Pottakkat, and M. T. Vasudevan Nair have added to Malayalam literature. Later, such contemporary Keralite Indian English writers as Booker Prize winner Arundhati Roy (whose 1996 semi-autobiographical bestseller The God of Small Things is set in the Kottayam town of Ayemenem) have garnered international recognition.

Kerala's music also has ancient roots. Carnatic music dominates Keralite classical music; this was the result of Swathi Thirunal Rama Varma's popularization of the genre in the 19th century.[69][70] Additionally, raga-based renditions known as sopanam accompany kathakali performances. Melam (including the paandi and panchari variants) is a more percussive style of music; it is performed at mandir-centered festivals using the chenda. Up to 150 musicians may comprise Melam ensembles, and performances may last up to four hours. Panchavadyam is a different form of percussion ensemble where up to one hundred artists use five types of percussion instruments. Kerala also has various styles of folk and tribal music. The popular music of Kerala — as in the rest of India — is dominated by the filmi music of Indian cinema.

Kerala has its own Malayalam calendar — this is used for timing agricultural and religious activities. Kerala's cuisine — pachakam — is typically served as a sadhya on green banana leaves; such spicy dishes as idli, payasam, pulisherry, puttucuddla, and puzhukku, rasam, and sambar are typical. Keralites — both men and women alike — traditionally don flowing and unstitched garments. These include the mundu, a loose piece of cloth wrapped around men's waists. Women typically wear the sari, a long and elaborately wrapped banner of cloth, wearable in various styles.

Several ancient ritualised arts are Keralite in origin; these include kalaripayattu (kalari ("place", "threshing floor", or "battlefield") and payattu ("exercise" or "practice")). Among the world's oldest martial arts, oral tradition attributes kalaripayattu's emergence to Parasurama. Other ritual arts include theyyam and poorakkali. However, Keralites are increasingly turning to more modern activities like cricket, kabaddi, soccer, and badminton. Dozens of large stadiums — including Kochi's Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium and Thiruvananthapuram's Chandrashekaran Nair Stadium — attest to the mass appeal of such sports among Keralites. Television (especially "mega serials" and cartoons) and the Internet have also impacted Keralite culture.[71] Yet Keralites maintain high rates of newspaper subscription — 50%[72] — spend some seven hours per week reading novels and other books,[71] host a sizeable "people's science" movement, and participate in such activities as writer's cooperatives.[58]

See also

Notes

References

External links

|

Wikiquote has quotations related to Kerala.

|