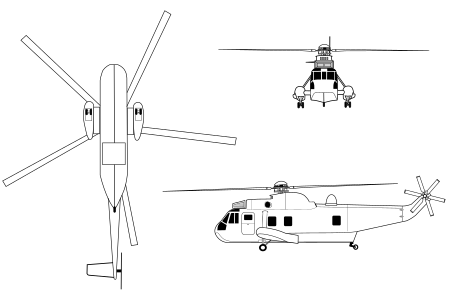

Westland Sea King

| WS-61 Sea King Commando | |

|---|---|

| |

| Royal Air Force Sea King HAR3A | |

| Role | Medium-lift transport/utility helicopter |

| Manufacturer | Westland Helicopters |

| First flight | 7 May 1969 |

| Status | Active service |

| Primary users | Royal Navy Royal Air Force Royal Australian Navy Indian Navy |

| Number built | 344 |

| Developed from | SH-3 Sea King |

The Westland WS-61 Sea King is a British licence-built version of the American Sikorsky S-61 helicopter of the same name, built by Westland Helicopters. The aircraft differs considerably from the American version, with Rolls-Royce Gnome engines (licence-built General Electric T58s), British made anti-submarine warfare systems and a fully computerised control system. The Westland Sea King was also produced as the Commando troop transport version for export.

Design and development

Origins

Westland Helicopters, which had a long standing licence agreement with Sikorsky to allow it to build Sikorsky's helicopters, extended the agreement to cover Sikorsky Sea King soon after the Sea King's first flight in 1959.[1] In 1966 the British Royal Navy selected the Sea King to meet a requirement for an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) helicopter to replace the Westland Wessex, placing an order with Westland for 60 Sea Kings on 27 June 1966.[2] The prototype and pre-production aircraft were constructed with Sikorsky-built components. The first Westland-built aircraft, the first production aircraft for the Royal Navy, designated the Sea King HAS1, first flew on the 7 May 1969 and was delivered to the navy in the same year.

By 1979, the Royal Navy had ordered 56 HAS1s and 21 HAS2s to meet the anti-submarine requirements, these were also outfitted for carrying out the secondary role of anti-ship missions.[3] Over 300 Westland Sea Kings were produced, the last to be built at Westland were Mk 43B SAR versions for the Royal Norwegian Air Force. The last of the Royal Navy's Sea Kings in the ASW role was retired in 2003, being replaced by the AgustaWestland Merlin HM1. The Airborne Surveillance and Control (ASaC) (formerly Airborne Early Warning) variant is expected to be replaced in time for the two Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers, some time in the 2010s. The types in contention are a Merlin derivative, a V-22 Osprey variant or a derivative of the E-2C Hawkeye. The UK is also expected to replace the HC4 and Search and Rescue variants in the 2010s.

The basic ASW Sea King has been upgraded numerous times, becoming the HAS2, HAS5 and HAS6, the latter of which has been replaced by the AgustaWestland Merlin ASW helicopter. Surviving aircraft are having the mission equipment removed and the aircraft are being used in the utility role.

Troop transport

A troop carrying version marketed as the Commando was developed for the Egyptian Air Force. A Commando variant, but retaining the folding blades and tail of the ASW variants, was designated the Sea King HC4 by the Royal Navy and is still in service as an important asset for amphibious assaults under the command of Commando Helicopter Force. It is capable of transporting 27 fully equipped troops with a range of 400 miles (640 km). Current Royal Naval Air Squadrons that operate the Commando variant are 845 Naval Air Squadron, 846 Naval Air Squadron and 848 Naval Air Squadron. The Sea King HC4 has been involved in operations in the Falklands, the Balkans, Gulf War I, Sierra Leone, Lebanon, Gulf War II and Afghanistan.

Some of the HAS6 fleet were re-purposed, by removing the ASW equipment, as Royal Marine troop transports. These aircraft were retired in 2010.[4]

Search and rescue

A dedicated Search and Rescue version (Sea King HAR3) was developed for the RAF Search and Rescue Force, the type entered service in 1978 to replace the Westland Whirlwind HAR.10.[5] A sixteenth aircraft was ordered shortly after, and following the Falklands War of 1982, three more aircraft were purchased to enable operation of a SAR flight in the islands, initially from Navy Point on the north side of Stanley harbour, and later from RAF Mount Pleasant. In 1992, six further aircraft were ordered to replace the last remaining Westland Wessex helicopters in the Search and Rescue role, entering service in 1996.[5] The six (Sea King HAR3A) had updated systems including a digital navigation system and more modern avionics.[5] Search and rescue versions of the Sea King were also produced for the Royal Norwegian Air Force, the German Navy and the Belgian Air Force.

As of 2006, up to 12 HAR3/3A were dispersed across the UK, a further 2 HAR3 were attached to the Falkland Islands; providing 24 hour rescue coverage.[5] Some Royal Navy HAS5 ASW variants were adapted for the Search and Rescue role and are currently in service with 771 Naval Air Squadron, Culdrose and HMS Gannet SAR Flight at Prestwick Airport in Scotland. They are expected to remain in service until 2018.[6]

Airborne early warning

The Royal Navy airborne early warning (AEW) capability had been lost when the Fairey Gannet aeroplane was withdrawn after the last of the RN's fleet carriers, HMS Ark Royal, was decommissioned in 1978. During the Falklands War, a number of warships were lost, with casualties, due to the lack of an indigenous AEW presence. The proposed fleet cover by the RAF Shackleton AEW.2 was too unresponsive and at too great a distance to be practical. Consequently, two Sea King HAS2s were modified in 1982 with the addition of the Thorn-EMI ARI 5930/3 Searchwater radar, attached to the side of the fuselage on a swivel arm and protected by an inflatable dome.[7] This allowed the helicopter to lower the radar below the fuselage in flight and to raise it for landing. These prototypes, designated Sea King HAS2(AEW), were both flying within 11 weeks and deployed with 824 "D" Flight on HMS Illustrious, serving in the Falklands after the cessation of hostilities. A further seven HAS2s were modified to a production standard, known as the Sea King AEW2.[7] These entered operational service in 1985, being deployed by 849 Naval Air Squadron. Four Sea King HAS5s were also later converted to AEW role as AEW5s, giving a total of thirteen AEW Sea Kings.[7]

An upgrade programme, Project Cerberus, resulted in the Sea King AEW fleet being upgraded with a new mission system based around the improved Searchwater 2000AEW radar from 2002 onwards.[7] This variant was initially referred to as the Sea King AEW7, but soon renamed ASaC7 (Airborne Surveillance and Control Mk.7).[8] The main role of the Sea King ASaC7 is detection of low flying attack aircraft. It also provides interception/attack control and over-the-horizon targeting for surface launched weapon systems. In comparison to older versions, the new radar enables the ASaC7 to simultaneously track 400 targets instead of the earlier 250 targets.

The ASaC7s will remain in service until they are replaced under the Future Organic Airborne Early Warning (FOAEW) programme, which will operate from the UK's future Queen Elizabeth class aircraft carrier.

Operational history

Falklands War

The Sea King was deployed during the Falklands War, performing mainly anti-submarine search and attack, and also replenishment, troop transport, and Special Forces insertions into the occupied islands. On 23 April 1982, a Sea King HC4 was ditched while performing a risky transfer of supplies to a ship at night, operating from the flagship HMS Hermes.[9]

Another Sea King was lost on 12 May, again from ditching into the sea, due to a systems malfunction. All of the Sea King's crew were rescued. Five days later, a Sea King, again from Hermes, crashed into the sea due to an altimeter problem; all crew were rescued.[10]

On 17 May 1982 a Sea King HC4 landed at Punta Arenas, Chile, and was subsequently destroyed by its crew. The three crew later gave themselves up to Chilean authorities. They were returned to the UK and were given gallantry awards for the numerous dangerous missions that they had undertaken. The official story was that the crew had become lost, although it was widely speculated that the helicopter had actually been inserting Special Air Service (SAS) soldiers onto the Argentine mainland.[11]

On 19 May 1982, a Sea King had been transporting SAS troops to HMS Intrepid from Hermes and was attempting to land on Intrepid. A thump was heard, and the Sea King dipped and crashed into the sea, killing 22 men. However, nine survived this accident, but only after jumping out of the Sea King just before the helicopter crashed. Bird feathers were found in the debris of the crash, which suggested that this accident was the result of a bird strike, though this theory is debated.[12] The SAS lost 18 men in the crash, their highest number of casualties on one day since the Second World War. The Royal Signals lost one man and the RAF one man. The latter was the only RAF fatality of the campaign.[citation needed]

Gulf War I

During the 1991 Gulf War Sea Kings roles included air-sea rescue, inter-ship transporting duties and transporting Royal Marines onto suspect ships that refused to turn around during the enforced embargo on Iraq. In addition two Sea King Mk5s from 826 Naval Air Squadron had their ASW sonar equipment removed and were equipped with a system for hunting sea mines called "Demon Camera". Six Sea King Mk4 helicopters from 845 Naval Air Squadron and six from 848 Squadron (which had been reformed and recommissioned that December) were deployed independently of the fleet. They provided support for the 1st Armoured Division. Initially based near King Khalid Military City, they followed the ground advance through Iraq into Kuwait.

Balkans

The Sea King participated in the UN's intervention in Bosnia, with Sea Kings operated by 820 Naval Air Squadron and 845 Naval Air Squadron. The Sea Kings from 820 NAS were deployed from Royal Fleet Auxiliary ships Fort Grange (since renamed Fort Rosalie) and Olwen. They provided logistical support, rather than the ASW role that the Squadron was geared towards, ferrying troops as well as supplies across the Adriatic Sea. They performed over 1,400 deck landings, flying in excess of 1,900 hours. The Sea Kings from 845 NAS performed vital casualty evacuation and other tasks. Their aircraft were hit numerous times, though no casualties were incurred.

During NATO's intervention in Kosovo, a British led operation, Sea Kings from 814 Naval Air Squadron, operated aboard HMS Ocean and RFA Argus and also on destroyers and frigates. They provided search and rescue (SAR), as well as transporting troops and supplies.

Gulf War II

During the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Sea King ASaC7 from 849 NAS operated off the flagship of the Royal Navy Task Force HMS Ark Royal. Sea King HC.4s also deployed from HMS Ocean (operated by 845 Naval Air Squadron) landing the lead invasion forces on the Al-Faw Peninsula, as well as Sea King HAS.6 from RFA Argus (operated by 820 Naval Air Squadron).

On 22 March 2003, two AEW Sea Kings from 849 NAS operating from Ark Royal collided over the Persian Gulf, killing six British and one American military personnel.

During the Gulf Wars the Sea Kings provided logistical support, transporting Royal Marines from their off-shore bases on Ark Royal, Ocean and other ships on to land in Kuwait.

Lebanon

In July 2006, Sea King HC.4 helicopters from RNAS Yeovilton were deployed to Cyprus to assist with the evacuation of British citizens from Lebanon. The UK mission was codenamed Operation Highbrow.[13]

Australia

Australia bought 12 Westland Sea King Mk 50s in 1974, replacing the Westland Wessex HAS31 as the Royal Australian Navy's Anti-Submarine Warfare helicopter. The aircraft were typically fitted with Racal ARI 5955/2 lightweight radar, Racal Navigation System RNS252, Racal Doppler 91, ADF Bendix/King KDF 806A and Tacan AN/ARN 118. All surviving Mk50 airframes were upgraded to Mk50A standard, through a mid-life extension. In 1995, the AQS-13B sonar was removed and since then, the Sea King's main role changed to maritime utility support.

Losses and replacements

During the first five years of operation, a number of aircraft were lost due primarily to a loss of main gearbox oil. Six Sea Kings were lost in accidents before 1995-6 when the remaining six were upgraded to Mk 50A standard. Additionally, a former Royal Navy HAS5 was acquired in 1996 and designated as a Mk 50B.

One of the upgraded Sea Kings was lost in 2005.

Australia has purchased and cannibalised five former Egyptian aircraft that were stripped in the United Kingdom to be used for spare parts and, in 2005, three Royal Navy aircraft were also obtained for spare parts.

End of service

On 1 September 2011, the Minister for Defence Materiel, Jason Clare, announced, “The Sea Kings will be withdrawn from service in December 2011. ...having flown in excess of 60,000 hours in operations in Australia and overseas.” A sale by Request for Tender was also announced, including:

- five complete helicopters;

- three airframes;

- a simulator; and

- associated unique equipment and parts.

[14][15] He had previously announced that Sea King Shark 07 would be preserved at the Fleet Air Arm Museum at HMAS Albatross, Nowra, New South Wales.

The Fleet Air Arm's Sea King fleet will be replaced earlier than was originally planned in response to the loss of a Sea King providing humanitarian aid in Indonesia in April 2005 due to mechanical failure. The crash resulted in the deaths of nine Australian military personnel. Australian Sea Kings played an integral part in the relief effort for the December 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, particularly in Indonesia's Aceh province where they delivered medical teams and aid supplies from Royal Australian Navy ships. The Australian Sea Kings will be replaced by the MRH 90.

The farewell flight was on Thursday 15 December 2011, from Nowra north along the coast to Sydney, New South Wales, where Shark 07, 21, and 22 flew over Sydney Harbour; then, south-west to the national capital, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, where they flew west-to-east along Lake Burley Griffin, near the Australian Parliament House, then along Anzac Parade and over the Australian War Memorial; then the flight returned overland to Nowra.

The Chief of Navy is to officiate at a ceremonial decomissioning of 817 Squadron RAN on Friday 16 December 2011, at NAS Nowra.

Variants

- Sea King HAS.1

- The first anti-submarine version for the Royal Navy. The Westland Sea King first flew in 1969.

- Sea King HAS.2

- Upgraded anti-submarine version for the Royal Navy. Some were later converted for AEW (Airborne Early Warning) duties.

- Sea King AEW.2

- Nine Sea King HAS.2s were converted into AEW aircraft, after lack of AEW cover was revealed during the Falklands War.

- Sea King HAR.3

- Search and rescue version for the Royal Air Force.

- Sea King HAR.3A

- Upgraded search and rescue version of the Sea King HAR.3 for the Royal Air Force.

- Sea King HC.4 / Westland Commando

- Commando assault and utility transport version for the Royal Navy. Capable of transporting 28 fully equipped troops.

- Sea King Mk.4X

- Two helicopters for trials at the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough.

- Sea King HAS.5

- Upgraded anti-submarine warfare version for the Royal Navy, some later converted into the HAR.5 for Search and Rescue.

- Sea King HAR.5

- Search and rescue version for the Royal Navy.

- Sea King AEW.5

- Four Sea King HAS.5s were converted into AEW helicopters for the Royal Navy.

- Sea King HU.5

- Surplus HAS.5 ASW helicopters converted into utility role for the Royal Navy.

- Sea King HAS.6

- Upgraded Anti-submarine warfare version for the Royal Navy.

- Sea King HAS.6(CR)

- Five surplus HAS.6 ASW helicopters converted into the utility role for the Royal Navy. The last of the Royal Navy's HAS.6(CR) helicopters was retired from service with 846 NAS on 31 March 2010.[4]

- Sea King ASaC7

- Upgraded AEW2/5 for the Royal Navy with Searchwater 2000AEW replacing original Searchwater radar.

- Sea King Mk.41

- Search and rescue version of the Sea King HAS.1 for the German Navy, with longer cabin; 23 built, delivered between 1973 and 1975. A total of 20 were upgraded from 1986 onwards with additional Ferranti Seaspray radar in nose and capability to carry four Sea Skua Anti-ship missiles.[16]

- Sea King Mk.42

- Anti-submarine warfare version of the Sea King HAS.1 for the Indian Navy; 12 built.[17]

- Sea King Mk.42A

- Anti-submarine warfare version of the Sea King HAS.2 for the Indian Navy, fitted with haul-down system for operating from small ships; three built.[18]

- Sea King Mk.42B

- Multi-purpose version for the Indian Navy, equipped for anti-submarine warfare, with dipping sonar and advanced avionics, and anti-shipping operations, with two Sea Eagle missiles; 21 built (one crashing before delivery).[18]

- Sea King Mk.42C

- Search and rescue/utility transport version for the Indian Navy with nose mounted Bendix search radar; six built.[18]

- Sea King Mk.43

- Search and rescue version of the Sea King HAS.1 for the Royal Norwegian Air Force, with lengthened cabin; 10 built.[19]

- Sea King Mk.43A

- Uprated version of the Sea King Mk.43 for the Royal Norwegian Air Force, with airframe of Mk.2 but engines of Mk.1. Single example built.[19]

- Sea King Mk.43B

- Upgraded version of the Sea King Mk.43 for the Royal Norwegian Air Force. Upgraded avionics, including MEL Sea Searcher radar in large dorsal radome, weather radar in nose and FLIR turret under nose. Three new-build plus upgrade of remaining Mk.43 and Mk.43A helicopters.[19]

- Sea King Mk.45

- Anti-submarine and anti-ship warfare version of the Sea King HAS.1 for the Pakistan Navy. Provision for carrying Exocet anti-ship missile; six built.[19]

- Sea King Mk.45A

- One ex-Royal Navy Sea King HAS.5 helicopter was sold to Pakistan as an attrition replacement.[20]

- Sea King Mk.47

- Anti-submarine version of the Sea King HAS.2 for the Egyptian Navy; six built.[20]

- Sea King Mk.48

- Search and rescue version for the Belgian Air Force. Airframe similar to HAS.2 but with extended cabin; five built, delivered 1976.[21]

- Sea King Mk.50

- Multi-role version for the Royal Australian Navy, equivalent to (but preceding) HAS.2; 10 built.[21]

- Sea King Mk.50A

- Two improved Sea Kings were sold to the Royal Australian Navy as part of a follow-on order in 1981.[22]

- Sea King Mk.50B

- Upgraded multi-role version for the Royal Australian Navy.

- Commando Mk.1

- Minimum change assault and utility transport version for the Egyptian Air Force, with lengthened cabin but retaining sponsons with floation gear.[22] Five built.[23]

- Commando Mk.2

- Improved assault and utility transport version for the Egyptian Air Force, fitted with more powerful engines, non-folding rotors and omitting undercarriage sponsons and floatation gear; 17 built.[24]

- Commando Mk.2A

- Assault and utility transport version for the Qatar Emiri Air Force, almost identical to Egyptian Mk.2; three built.[25]

- Commando Mk.2B

- VIP transport version of Commando Mk.2 for the Egyptian Air Force; two built.[25]

- Commando Mk.2C

- VIP transport version of Commando Mk.2A for the Qatar Emiri Air Force; one built.[25]

- Commando Mk.2E

- Electronic warfare version for the Egyptian Air Force, fitted with integrated ESM and jamming system, with radomes on side of fuselage; four built.[26]

- Commando Mk.3

- Anti-ship warfare version for the Qatar Emiri Air Force, fitted with dorsal radome and capable of carrying two Exocet missiles.[26]

Operators

Specifications (Sea King HAS.5)

Data from Omnifarious Sea King [29]

General characteristics

- Crew: Two to four, depending on the mission

Performance

Armament

- 4× Mark 44, Mark 46 or Sting Ray torpedos, or 4× Depth charges

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

- Notes

- ^ James 1991, pp. 377–378.

- ^ Air International May 1981, p.215.

- ^ Hewish 1979, p. 76.

- ^ a b Allen, Peter. "UK RN retires final Commando Sea King Mk 6CR." Jane's Defence Weekly, Volume 47, Issue 2, p. 33, 2 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d Ministry of Defence 2006, p. 120.

- ^ Carrara 2009, pp. 78–82.

- ^ a b c d Westland Sea King AEW2 and ASaC.7

- ^ Cerberus set for service aboard Sea King Whiskey, Upgrade Update

- ^ Burden et al. 1986, p. 251.

- ^ Burden et al. 1986, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Preliminary British Operations (Parts 20-30), Part 30. Sea King-to-Chile Incident, Operations leading up to San Carlos Landings 17th-20th MAY 1982." Naval History. Retrieved: 25 January 2011.

- ^ Burden et al. 1986, p. 253.

- ^ "Helicopters go to aid evacuation." BBC News, 18 July 2006.

- ^ Minister for Defence Materiel – Navy Sea King helicopters for sale, Jason Clare, 1 September 2011, accessed 12 September 2011

- ^ Australia selling off its last Sea Kings, spacewar.com, 8 September 2011, accessed 12 September 2011

- ^ Lake 1996, p. 128.

- ^ Lake 1996, pp. 128–129.

- ^ a b c Lake 1996, p. 129.

- ^ a b c d Lake 1996, p.130.

- ^ a b Lake 1996, p. 131.

- ^ a b Lake 1996, p. 132.

- ^ a b Lake 1996, p. 133.

- ^ James 1991, p. 392.

- ^ Lake 1996, pp. 133–134.

- ^ a b c Lake 1996, p. 134.

- ^ a b Lake 1996, p. 135.

- ^ "The NAWSARH Project." Royal Norwegian Ministry of Justice and the Police. Retrieved: 23 July 2010.

- ^ Dalløkken, Per Erlie. "De fem kandidatene." (in Norwegian) Teknisk Ukeblad, 5 June 2009. Retrieved: 23 July 2010.

- ^ Air International May 1981, p. 218.

- ^ James 1991, pp. 396–398.

- Bibliography

- Allen, Patrick. Sea King. London: Airlife, 1993. ISBN 1-85310-324-1.

- Burden, Rodney A., Michael A. Draper, Douglas A. Rough, Colin A Smith and David Wilton. Falklands: The Air War. Twickenham, UK: British Air Review Group, 1996. ISBN 0 906339 05 7.

- Carrara, Dino. "Sea Kings to the Rescue". Air International, Vol. 77, No. 6, December 2009, pp. 78–82. ISSN 0306-5634.

- Chartres, John. Westland Sea King: Modern Combat Aircraft 18. Surrey, UK: Ian Allen, 1984. ISBN 0-7110-1394-2.

- Eden, Paul (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. London: Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 1-904687-84-9.

- Gibbings, David. Sea King: 21 years Service with the Royal Navy. Yeovilton, Somerset, UK: Society of Friends of the Fleet Air Arm Museum, 1990. ISBN 0-9513139-1-6.

- Hewish, Mark. Air Forces of the World: An Illustrated Directory of All the World's Military Air Powers. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1979. ISBN 0-6712508-6-8.

- James, Derek N. Westland Aircraft since 1915. London: Putnam, 1991. ISBN 0-85177-847-X.

- Lake, Jon. "Westland Sea King: Variant Briefing". World Air Power Journal, Volume 25, Summer 1996, pp. 110–135. London: Aerospace Publishing. ISBN 1-847023-79-4. ISSN 0959-7050.

- Ministry of Defence. "The Royal Air Force handbook: the definitive MoD guide". Conway, 2006. ISBN 1-857533-84-4.

- Uttley, Matthew. Westland and the British Helicopter Industry, 1945-1960: Licensed Production versus Indigenous Innovation. London: Routledge, 2001. ISBN 071465194X.

- "Westland's Multi-rôle Helicopter Family: Omnifarious Sea King". Air International, Vol. 20, No. 5, May 1981, pp. 215–221, 251–252. ISSN 0306-5634.