Invention of radio

In the history of radio and development of "wireless telegraphy", there are multiple claims to the invention of radio. The most commonly accepted claims to the invention of radio are those of Nikola Tesla and Guglielmo Marconi.

Develoment of radio

In the late 1800s, it was clear to various scientists and experimenters that wireless communication was possible. Various theoretical and experimental innovations lead to the development of radio and the communication system we know today. Some early work was done by local effects and experiments of electromagnetic induction. Wireless telegraphy was beginning to take hold and the practice of transmitting messages without wires was being developed. Many people worked on developing the devices and improvements.

Marconi

After the 1880s Hertz experiments, Guglielmo Marconi's proponents state that he read about the work while on vacation in 1894 (which was the same year Hertz passed away). Marconi wondered if radio waves could be used for wireless communications. [1] Marconi’s early apparatus was a development of Hertz’s laboratory apparatus into a system designed for communications purposes. At first he used a transmitter to ring a bell in a receiver in his attic laboratory. He then moved his experiments out-of-doors on the family estate near Bologna, Italy, to communicate over larger distances. He replaced Hertz’s vertical dipoles by a vertical wire topped by a metal sheet, together with an opposing terminal that had a ground connection. The Marconi antenna was a vertical quarterwave monopole conductor, with no loading coil nor capacitive top load, and base driven by a regular power supply with a suitable matching section. Marconi replaced the spark gap in his receiver by the metal powder coherer, a detector developed by Edouard Branly and other experimenters (ed., it was named by Oliver Lodge).

He transmitted radio signals a distance of about a mile at the end of 1895. [2] Marconi's reputation is based, in large measure, on this accomplishments in radio communications and the practical system he developed. His demonstrations of the use of radio for wireless communications, equipping ships with life saving wireless communications, establishing the first transatlantic radio service, and building the first stations for the British short wave service. Marconi and his company were not alone in the field; his principle competition came from German scientists whose work would become the basis for the Telefunken company (and whom Nikola Tesla assisted in the building).

Marconi's U.S. patent 586,193 (July 13, 1897) (and the reissued U.S. patent RE11913) disclosed a two-circuit system for the transmission and reception of "Hertzian waves" (though he would later acknowledge that in the early wireless systems the "waves do not propagate in the same manner as free radiation from a classical Hertzian oscillator, but glide along the surface of the Earth" [3]). The transmitter was an antenna circuit, with a aerial plate and a ground plate, and a spark gap. Induced signals in the circuit was caused to discharge through a spark gap, producing oscillations which were radiated. The receiver contained an antenna circuit, an aerial plate and a ground plate, and a coherer. Marconi's apparatus was to be resonant (commonly called by some at the time as "syntonic"). This was done by the careful determination of the size of the aerial plates.

In 1901, Marconi claimed to have received daytime transatlantic radio short wave (HF) frequencies signals at a wavelength of 366 metres (820 kHz). [4] [5] [6] The early spark transmitters may have been broadly tuned and the Poldhu transmitter may have radiated sufficient energy in that part of the spectrum for a transatlantic transmission, if Marconi was using an untuned receiver when he claimed to have received the transatlantic signal at Newfoundland in 1901. When he used a tuned receiver aboard the SS Philadelphia in 1902, he could only receive a daytime signal from Poldhu a distance of 700 miles, less than half the distance from Poldhu to Newfoundland. At night the signals were reported to have been received several times further, and his successful transatlantic transmissions from Glace Bay, Nova Scotia in 1902 were made at night. Marconi would later found the Marconi Company and would jointly recieve the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physics with Karl Ferdinand Braun.

Case against Marconi

Marconi’s late-1895 transmission of signals, a distance of around a mile, was small compared to Tesla's early-1895 tansmissions of up to 50 miles. Marconi’s 1901 Poldhu - Newfoundland transmission claim is also highly improbable. [7] Critics have stated that it is more likely that Marconi received stray atmospheric noise from atmospheric electricity in the 1901 experiment.[8]

In addition, prior work was conducted by others (such as by Hertz, Tesla, Lodge, Bruan, and Stone) from which a percentage of Marconi's devices and methods were derived. Marconi's U.S. patent 676,332 Apparatus for wireless telegraphy [1901], in which a more developed system was disclosed than in his earlier patents, was well after contributions made by other investigators.

Tesla

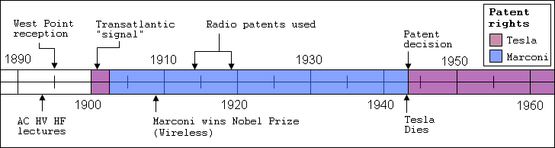

Nikola Tesla initially held the rights to radio. He had U.S. patent 649,621, "Apparatus for Transmission of Electrical Energy" (May 15, 1900; filed Feb. 19, 1900), division of U.S. patent 645,576 "System of Transmission of Electrical Energy", March 20, 1900 (March 20, 1900; filed Sept. 2, 1897). In US649621, Tesla established a system which was composed of a transmitting coil (or conductor) arranged and excited to cause oscillations (or currents) to propagate via conduction through the natural medium from one point to another remote point therefrom and a receiver coil, or conductor, of the transmitted signals. In US645576, Tesla cited the well known radiant energy phenomena and corrected previous errors in theory of behavior. Within this specifications, Tesla declared, "The apparatus which I have shown will obviously have many other valuable uses - as, for instance, when it is desired to transmit intelligible messages to great distances [...]".

Tesla's aerial parameters consisted of a small (as to distribution of height) vertical high aspect-ratio quarterwave helical resonator, possessing a top load of large capacitive, which was driven at the base by a regular power supply and suitable matching section. The aerials' opposing terminal was grounded. Tesla’s vertical structure could radiate as common "hertzian" antenna, if driven in a certian fashion, but would resonate, though, if the driving circuitry was arranged properly. Some of the roughly hemispherical shaped conductors that Tesla used had a capacitance comparable to that of a large radio antenna. The applied voltage caused an oscillating current to flow between the earth and the elevated conductor, as it does in a conventional low frequency radio transmitter with a vertical radio antenna and ground.

Tesla’s structure could also inject a large alternating current into the earth via the ground terminal. Tesla's, not Marconi's, discovery of great importance was of the "groundwave" method. The method to produce surface waves was the consequence of adding a ground connection to the transmitter. Tesla stated, in 1893, that

- One of the terminals of the source would be connected to earth [...] the other to an insulated body of large surface. [9]

This method led to larger and longer transmission ranges. Many AM stations use this same principle to boost reception of thier signals. [10]

It has also been noted that Tesla was one of the first to patent a means to reliably produce radio frequencies. Tesla's U.S. patent 447,920, "Method of Operating Arc-Lamps" (March 10, 1891), describes an alternator that produces high-frequency current for that time period, around 10,000 cycles per second (later to be known as hertz). Though his patentable innovation was to suppress the disagreeable sound of power-frequency harmonics produced by arc lamps operating on frequencies within the range of human hearing, the frequency produced by the device was in the longwave broadcasting range (VLF band). Around July of 1891, after becoming a naturalized citizen of the United States, he established his New York laboratory and constructed various apparatus that produced between 15,000 to 18,000 cycles per second. At this location, he also lit vacuum tubes wirelessly (thus providing hard evidence for the potential of wireless transmissions).

In the beginning of 1895, Tesla was able to detect signals from the transmissions of his New York lab at West Point (a distance of 50 miles). [11] By early 1896, he attained devices that produced undamped (or continous) waves around 50,000 cycles per second[12] and, between 1895 and 1898, Tesla continued his research into wireless transmission principles. After travelling to Colorado Spring (around 1899), Telsa lit a bank of incandescent bulbs wirelessly at very long distances during his experiments with the magnifying transmitter.

Shortly after the turn of the 20th century, the US Patent Office reversed its decision on the priority of radio and awarded Marconi the patent for radio. Tesla fought to re-acquire his radio patent, but failed. A lawsuit regarding Marconi's numerous other radio patents was resolved by the U.S. Supreme Court, who overturned most of these (1943). At the time, the United States Army was involved in a patent infringement lawsuit with Marconi's company regarding radio, leading some to posit that the government nullified Marconi's other patents in order to moot any claims for compensation (as, some posit, the government's initial reversal to grant Marconi the patent right in order to nullify any claims Tesla had for compensation).

The court decision was based on the proven prior work conducted by others, such as by Tesla, Oliver Lodge, and John Stone Stone, from which some of Marconi patents (such as U.S. patent 763,772) stemmed. The U. S. Supreme Court stated that,

- "The Tesla patent No. 645,576, applied for September 2, 1897 and allowed March 20, 1900, disclosed a four-circuit system, having two circuits each at transmitter and receiver, and recommended that all four circuits be tuned to the same frequency. [... He] recognized that his apparatus could, without change, be used for wireless communication, which is dependent upon the transmission of electrical energy." [13]

In making thier decision, the court noted,

- "Marconi's reputation as the man who first achieved successful radio transmission rests on his original patent, which became reissue No. 11,913, and which is not here [320 U.S. 1, 38] in question. That reputation, however well-deserved, does not entitle him to a patent for every later improvement which he claims in the radio field. Patent cases, like others, must be decided not by weighing the reputations of the litigations, but by careful study of the merits of their respective contentions and proofs." [14]

The court also stated that,

- "It is well established that as between two inventors priority of invention will be awarded to the one who by satisfying proof can show that he first conceived of the invention." [15]

Transmission and radiation of radio frequency energy was a feature exhibited in the experiments by Tesla and was noted early on to be used for the telecommunication of information. [16][17] In 1892, Tesla delivered a widely reported presentation before the Institution of Electrical Engineers of London in which he noted, among other things, that intelligence would be transmitted without wires. Later, a variety of Tesla's radio frequency systems were demonstrated during another widely known lecture, presented to meetings of the National Electric Light Association in St. Louis, Missouri and the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia. According to the IEEE, "the apparatus that he employed contained all the elements of spark and continuous wave that were incorporated into radio". [18]

Marconi supporters have stated that Marconi was not aware of the works of Nikola Tesla in the United States. It is unlikely, though, that Marconi was unaware of Tesla's presentations. Both "On Light and Other High Frequency Phenomena" (Philadelphia/St. Louis; Franklin Institute in 1893) and "Experiments with Alternating Currents of High Potential and High Frequency" (London; 1892) were reported on internationally. Tesla's 1893 presentation at the Franklin Institute was reported across America (such as in the Century Magazine) and throughout Europe.[19] Tesla also did perform public demonstrations of actual and related work, such the remote-controlled boat in 1898 (of which was protected under U.S. patent 613,809). The remote-controlled boats contained "rotating coherers" that allowed secure communication between transmitter and receiver.

Tesla believed that his wireless system would be better than conventional radio because traverse electromagnetic waves (whose behavior depends on its wavelength) would decay as they travelled from the transmitter, making the signals uselessly weak at long distances, whereas he believed that longitudinal electromagnetic waves (such as those that occur in waves in plasmas) through the medium would be practically lossless. Besides his intention to transmit wireless signals of intelligence, he proposed to transmit electric power via electrical conduction through the Earth and the upper atmosphere, as well as inbetween them both (in the Earth-ionosphere region which is now known as a resonante cavity). This power transmission was to be done not by "hertzian waves", but through standing surface waves. Tesla’s proposed wireless transmitter utilized a resonant transformer to apply a very high voltage of high frequency between the earth and a large elevated conductor, as discussed earlier.

Case against Tesla

It is a popular belief, some would say misconception, that Tesla had a small influence on the development of radio. Tesla never did complete his "worldwide wireless system", primarily because of financial difficulties. Cost overruns prevented him from completing the wireless station tower that he built in the early 1900s on Long Island, New York. Some, mostly Marconi's supporters, dispute the relevancy of his remote-controlled boat demonstrations as well as his public lecture demonstrations.

Other pioneers

Many scientists and inventors contributed to the invention of wireless telegraphy and radio. Individuals that helped to further the science include, among others, Jozef Murgaš (extensive work in the late 1890s), Oliver Lodge (transmitted radio signals, one year before Marconi but one year after Tesla), Hans Christian Ørsted (researched how the magnetic fields radiated from a "live wire"), Michael Faraday (developed the idea of electromagnetic induction), David E. Hughes (early experiments with transmission and reception), Thomas Alva Edison (U.S. patent 465,971; 1891), Nathan Stubblefield (U.S. patent 887,357; 1908).

Below are more investigators that reportedly have claims to the invention of radio.

Alexander Popov

Alexander Popov would describe his findings concerning the wireless arts in a paper published that same year in 1895. Popov died in 1905 and his claim was not pressed by the Russian government until 40 years later. Popov's early experiments were transmissions of only 600 yards. [20] Popov's public demonstration of the transmission of radio waves, between different campus buildings, to the Saint Petersburg Physical Society (around March, 1896) was before the public demonstration of the Marconi system (around September, 1896). In 1900, Popov stated (in front of the Congress of Russian Electrical Engineers),

- "[...] the emission and reception of signals by Marconi by means of electric oscillations [was] nothing new. In America, the famous engineer Nikola Tesla carried the same experiments in 1893." [21]

Popov would also experiment with ship-to-shore communication. [22] These 1898 experiments were at a distance of 6 miles. The experiments in 1899 were transmitted to a distance of 30 miles.

Heinrich Hertz

In his classic UHF experiments, Heinrich Hertz had verified that the properties of radio waves were consistent with Maxwell’s electromagnetic theory. Of the three basic forms of wireless aerial launching structures common at the time, the Hertz antenna was a vertical dipole, center fed, half wavelength structure. No ground connection was used. Hertz’s source and detector of radio waves might be regarded as a type of primitive radio transmitter and receiver, but the transmitter was not very good for actual use at the low frequencies that the early wireless systems used. Hertz used the damped oscillating currents in a dipole antenna, triggered by a high voltage electrical spark discharge, as his source of radio waves. His detector in some experiments was another dipole antenna connected to a narrow spark gap. A small spark in this gap signified the detection of the radio wave. When he added cylindrical reflectors behind his dipole antennas, Hertz was able to detect radio waves about 20 metres from the transmitter in his laboratory. He did not try to extend this distance further because he was motivated by verifying electromagnetic theory, not by developing wireless communications. In Marconi's 1895 experiments, he followed Hertz's work (among others) by using a spark source in what became known as a spark-gap transmitter.

Jagdish Chandra Bose

Another pioneer of wireless communication was Prof Jagdish Bose. In 1894, Bose ignited gunpowder and rang a bell at a distance using electromagnetic waves, replicating independently that communication signals can be sent without using wires. In 1896, the Daily Chronicle of England reported on his UHF experiments:

- "The inventor (J.C. Bose) has transmitted signals to a distance of nearly a mile and herein lies the first and obvious and exceedingly valuable application of this new theoretical marvel."

Popov, in Russia, was doing similar experiments but had written, in December 1895, that he was still entertaining the hope of remote signalling with radio waves. The wireless signalling experiment by Marconi on Salisbury Plain in England was not until May 1897. The 1895 public demonstration by Bose in Calcutta predates this experiment. [23] [24] Both of Bose's experiments, though, was well after Tesla's demonstration of radio communication in 1892 and 1893.

Bose, it has been noted, was not interested in the commercial applications of the experiment's transmitter. He did not attempt to file patent protection for sending signals. In 1899, Bose announced the development of a "iron-mercury-iron coherer with telephone detector" in a paper presented at Royal Society, London. [25] Later, he received U.S. patent 755,840, "Detector for electrical distrubances" (1904), for a specific electromagntic receiver. While he is not known for greatly contributing to the development of commercial radio communication and did not file any patents for transmission, this doesn't discount that he does deserves recognition for contributing to the development of radio.

M. Loomis and W. H. Ward

Mahlon Loomis of West Virginia has the oldest and most documented claim of inventing radio. Loomis received U.S. patent 129,971 for a "wireless telegraph" in 1872. This patent utilizes atmospheric electricity to eliminate the overhead wire used by the existing telegraph systems. It did not contain diagrams or specific methods. It is substantially similar to U.S. patent 126,356 received three months earlier by William Henry Ward.

Music group album

The band named "Tesla" has an album, The Great Radio Controversy, which is titled after this controversy of the identity of the inventor of radio. The album inner sleeve recounts the story where the Serbian-American engineer Tesla (who the band is named after) is the true inventor of radio, while the Italian Marconi took the credit and is widely regarded with the title.

References

General information and overview articles

- Leland Anderson, "Nikola Tesla On His Work With Alternating Currents and Their Application to Wireless Telegraphy, Telephony, and Transmission of Power", Sun Publishing Company, LC 92-60482, ISBN 0-9632652-0-2 (ed. excerpts available online)

- Sungook Hong, "Wireless: from Marconi's Black-box to the Audion", Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001, ISBN 0262082985

- "A Comparison of the Tesla and Marconi Low-Frequency Wireless Systems ". Twenty First Century Books, Breckenridge, Co..

- Thomas H. White, "Pioneering U.S. Radio Activities (1897-1917)", United States Early Radio History.

- A. David Wunsch, "Misreading the Supreme Court: A Puzzling Chapter in the History of Radio". Mercurians.org.

Citations and notes

- ^ Henry M. Bradford, "Marconi's Three; Transatlantic Radio Stations In Cape Breton". Read before the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society, 31 January 1996. (ed. the site is reproduced with permission from the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society Journal, Volume 1, 1998.)

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Henry M. Bradford, "Marconi in Newfoundland: The 1901 Transatlantic Radio Experiment".

- ^ Henry M. Bradford, "Did Marconi Receive Transatlantic Radio Signals in 1901? - Part 1". Wolfville, N.S..

- ^ Henry M. Bradford, "Did Marconi Receive Transatlantic Radio Signals in 1901? Part 2, Conclusion: The Trans-Atlantic Experiments". Wolfville, N.S..

- ^ John S. Belrose, "Fessenden and Marconi; Their Differing Technologies and Transatlantic Experiments During the First Decade of this Century", International Conference on 100 Years of Radio, 5-7 September, 1995, (PDF file; ed. accessed April 14, 2006)

- ^ Sungook Hong, "Marconi's Error: The First Transatlantic Wireless Telegraphy in 1901", Social Research, vol. 72, p. 107, March 22, 2005

- ^ Ibid.; The quote is from, Marconi, "Wireless Telegraphic Communication: Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1909." Nobel Lectures. Physics 1901-1921. Amsterdam: Elsevier Publishing Company, 1967: 196-222.

- ^ "Why AM Radio Stations Must Reduce Power, Change Operations, or Cease Operations at Night". fcc.gov.

- ^ PBS: Marconi and Tesla: Who invented radio? (ed. this is noted as having been accomplished in Leland's book concerning Tesla's "Work with Alternating Currents" [see general information section])

- ^ Covered in Leland's book concerning Tesla's "Work with Alternating Currents".

- ^ U.S. Supreme Court, "Marconi Wireless Telegraph co. of America v. United States". 320 U.S. 1. Nos. 369, 373. Argued April 9-12, 1943. Decided June 21, 1943.

- ^ "Experiments with Alternating Currents of High Potential and High Frequency". Delivered before the Institution of Electrical Engineers, London, February 1892.

- ^ "On Light and Other High Frequency Phenomena". Delivered before the Franklin Institute, Philadelphia, February 1893, and before the National Electric Light Association, St. Louis, March 1893.

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ "Nikola Tesla, 1856 - 1943". IEEE History Center, IEEE, 2003.

- ^ Ljubo Vujovi, "Tesla Biography; Nikola Tesla, The genius who lit the world". Teslasociety.com.

- ^ "The Work of Jagdish Chandra Bose: 100 years of mm-wave research". tuc.nrao.edu.

- ^ "The Electronic Era; When? Where? Who? How? Why?". First Electronic Church Of America.

- ^ "Russia's Popov: Did he "invent" radio?". The First Electronic Church of America.

- ^ "The Guglielmo Marconi Case Who is the True Inventor of Radio".

- ^ "Jagadish Chandra Bose", ieee-virtual-museum.org.

- ^ Bondyopadhyay, Probir K., "Sir J. C. Bose's Diode Detector Received Marconi's First Transatlantic Wireless Signal Of December 1901 (The "Italian Navy Coherer" Scandal Revisited)". Proc. IEEE, Vol. 86, No. 1, January 1988.

External articles and further readings

- Readings

- Weightman, Gavin, "Signor Marconi's magic box : the most remarkable invention of the 19th century & the amateur inventor whose genius sparked a revolution" 1st Da Capo Press ed., Cambridge, MA : Da Capo Press, 2003.

- Garratt, G. R. M., "The early history of radio : from Faraday to Marconi", London, Institution of Electrical Engineers in association with the Science Museum, History of technology series, 1994. ISBN 0852968450 LCCN gb 94011611

- Masini, Giancarlo. "Guglielmo Marconi". Turin: Turinese typographical-publishing union, 1975. LCCN 77472455 (ed. Contains 32 tables outside of the text)

- Geddes, Keith, "Guglielmo Marconi, 1874-1937". London : H.M.S.O., A Science Museum booklet, 1974. ISBN 0112901980 LCCN 75329825 (ed. Obtainable in the U.S.A. from Pendragon House Inc., Palo Alto, California.)

- Coe, Douglas and Kreigh Collins (ills), "Marconi, pioneer of radio". New York, J. Messner, Inc., 1943. LCCN 43010048

- Waldron, Richard Arthur, "Theory of guided electromagnetic waves". London, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1970. ISBN 0442091672 LCCN 69019848 //r86

- Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Company, "Year book of wireless telegraphy and telephony", London : Published for the Marconi Press Agency Ltd., by the St. Catherine Press / Wireless Press. LCCN 14017875 sn 86035439

- Hancock, Harry Edgar, "Wireless at sea; the first fifty years. A history of the progress and development of marine wireless communications written to commemorate the jubilee of the Marconi International Marine Communication Company limited". Chelmsford, Eng., Marconi International Marine Communication Co., 1950. LCCN 51040529 /L

- Websites

- Leland I. Anderson, Priority in the Invention of Radio — Tesla vs. Marconi, Antique Wireless Association monograph, 1980, examining the 1943 decision by the US Supreme Court holding the key Marconi patent invalid (9 pages). (21st Century Books)

- Guglielmo Marconi and Early Systems of Wireless Communication accessed April 14, 2006 (PDF file) from Marconi.com

- Katz, Randy H., "Look Ma, No Wires": Marconi and the Invention of Radio". History of Communications Infrastructures.