Life of Joseph Smith from 1831 to 1834

| This article is part of a series on |

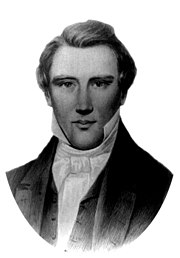

| Joseph Smith |

|---|

|

The life of Joseph Smith, Jr. from 1831 to 1844 covers the period of time from when Smith moved with his family to Kirtland, Ohio in 1831, to his death in 1844. By this time, Smith had already translated the Book of Mormon, and established the Latter Day Saint movement. He had founded it as the Church of Christ, but was eventually called by revelation to change its name to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.[1]

Life in Kirtland, Ohio

After being instructed by revelation[2], Smith and his wife Emma Hale Smith moved to Kirtland, Ohio early in 1831. It has been thought that this may have been to avoid conflict and persecution encountered in New York and Pennsylvania. They lived with Isaac Morley's family while a house was built for them on the Morley farm. Many of Smith's followers and associates settled in Kirtland, and also in Jackson County, Missouri, where Smith said he was instructed by revelation to build Zion.

The early Church grew rapidly.

Early conflicts

There were often conflicts between the Saints and their neighbors. These conflicts were sometimes violent: on the evening of March 24, 1832 in Hiram, Ohio, a group of men beat and tarred and feathered Smith and his counselor Sidney Rigdon. They threatened Smith with castration and with death, and one of his teeth was chipped when they attempted to force him to drink poison. The mob action led to the exposure and eventual death of Smith's adopted newborn twins. Rigdon suffered a severe concussion after being dragged on the ground. According to some accounts, Rigdon was delirious for several days. The reasons for this attack are uncertain, but likely were tied to a sermon given by Rigdon.

In his book, Under the Banner of Heaven, author Jon Krakauer links this particular episode to a sexual liaison Smith purportedly had with Benjamin F. Johnson's fifteen-year-old daughter, Miranda Nancy Johnson. Krakauer quotes Miranda's older brother Luke Johnson as saying that the mob "had Dr. Dennison there to perform the operation [of castration]; but when he saw the Prophet stripped and stretched on the plank, his heart failed him and he refused to operate."

Todd Compton, author of In Sacred Loneliness: The Plural Wives of Joseph Smith reports that evidence of a relationship or marriage between Joseph and Miranda is not compelling. Miranda herself wrote, “Here I feel like bearing my testimony that during the whole year that Joseph was an inmate of my father’s house I never saw aught in his daily life or conversation to make me doubt his divine mission.” (231–32)

After tending to his wounds all night and into the early morning, Smith preached a sermon on forgiveness the following day. Though some reports state that members of the mob that had attacked him were present at this sermon, Smith did not mention the attack directly.

Zion's Camp

As early as 1831, Smith had stated that the City of Zion would be built in Jackson County with Independence, Missouri as the centerplace for Zion.[3] Many Latter Day Saints began to gather to that area. Many local non-Mormons in Jackson County became alarmed at the movement's rapid growth. Forming vigilante groups, many burned Latter Day Saint homes and destroyed the church print shop. Many Latter Day Saints were threatened and abused and by 1833, nearly all had fled from the county for their safety. The Mormon refugees then settled temporarily in neighboring counties, including Clay County in particular.

In 1834, Smith called for a militia to be raised in Kirtland which would then march to Missouri and "redeem Zion."[4] About 200 men and a number of women and children volunteered to join this militia which became known as "Zion's Camp." It was agreed that Smith would be the leader of the group.

Zion's Camp left Kirtland on May 4, 1834. They had marched across Indiana and Illinois Rivers, reached the Mississippi River, and entered Missouri by June 4. They crossed most of the state by the end of June and news of their approach caused some alarm among non-Mormons in Jackson and Clay Counties. Attempts to negotiate a return of the Latter Day Saints to Jackson County proved fruitless, but Smith decided to disband Zion's Camp, rather than attempt to "redeem Zion" by force. Many members of the camp subsequently became ill with cholera.

Although the Latter Day Saints failed to achieve their goal of returning to Jackson County, Missouri's legislature later approved a compromise which set aside the new county of Caldwell, specifically for their settlement in 1836.

While the march failed to return Latter Day Saint property, many of its participants became committed loyalists in the movement. When Smith returned to Kirtland, he organized the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and the First Quorum of the Seventy, choosing primarily men who had served in Zion's Camp.

Temple in Kirtland

In Kirtland, the church's first temple was built. Work was begun in 1833, and the temple was dedicated in 1836. At and around the dedication, many extraordinary events were reported: appearances by Jesus, Moses, Elijah, Elias, and numerous angels; speaking and singing in tongues, often with translations; prophesying; and other spiritual experiences. Some Mormons believed that Jesus' Millennial reign had come.

Later life in Kirtland

On January 12, 1838 Smith and Rigdon left Kirtland for Far West in Caldwell County, Missouri, in Smith's words, "to escape mob violence, which was about to burst upon us under the color of legal process to cover the hellish designs of our enemies." Just prior to their departure, many Saints (including prominent leaders) became disaffected in the wake of the Kirtland Safety Society debacle, in which Smith and several associates were accused of various illegal or unethical banking actions.

Most of the remaining church members left Kirtland for Missouri.

Life in Missouri

Smith's early revelations identified western Missouri as Zion, the place for Mormons to gather in preparation for the second coming of Jesus Christ. Independence, Missouri, was identified as "the center place" and the spot for building a temple.[5] Smith first visited Independence in the summer of 1831, and a site was dedicated for the construction of the temple. Soon afterward, Mormon converts—most of them from the New England area—began immigrating in large numbers to Independence and the surrounding area.

The Latter Day Saints had been migrating to Missouri ever since Smith had claimed the area to be Zion. They simultaneously occupyed the Kirtland area, as well as the Independence area for around seven years. After Smith had been forced out of Kirtland in 1838, he, and the rest of the remaining Latter Day Saints from Kirtland, came to Missouri.

The Missouri period was marked by many instances of violent conflict and legal difficulties for Smith and his followers.

A recent article (Jan 4, 2006 Kansas City Star) describes some of the details of these events, based on legal documents recovered in 2001:

"Majors, Owens, McCarty, Fristoe. To those familiar with pioneers of Jackson County, it's a short roll call of some of its finest. At the same time, they are four of 54 residents who in 1833...were named as defendants in a lawsuit prompted by the tarring and feathering of two Independence followers of...Joseph Smith Jr."

The defendants were found guilty and fined one cent each. Within four months 800 followers of Joseph Smith were forcibly dispossessed of their homes and businesses. A long trail of appeals went as far as Washington D.C. with Joseph receiving a personal audience with President Martin Van Buren, who said he could not help. Congress sent the matter back to the state of Missouri.

Many people saw their new LDS neighbors as a religious and political threat. Mormons tended to vote in blocs, giving them a degree of political influence wherever they settled. Additionally, Mormons purchased vast amounts of land in which to establish settlements. The majority of Saints were northerners and held abolitionist viewpoints, including Smith himself, clashing with the pro-slavery persuasions of the Missourians. The tension was fueled by the belief that Jackson County, Missouri, and the surrounding lands were promised to the Church by God and that the Saints would soon dominate it. All of these factors contributed to aggressive mob violence and other harassments.

Mob violence

In response to the consistent persecution, a small group of Latter Day Saints organized themselves into a vigilante group called the Danites, led by Dr. Sampson Avard. Smith's exact role in the Danite society is unknown; some suggest that he held a leading or even founding position, while others believe he had no knowledge of the Danites before their existence was publicly recognized. Later, Smith stated that he disapproved of the group and Avard was excommunicated for his activities. [6]

Soon the "old Missourians" and the LDS settlers were engaged in a conflict sometimes referred to as the 1838 Mormon War. One key skirmish was the Battle of Crooked River, which involved Missouri state troops and a group of Saints. There is some debate as to whether the Mormons knew their opponents were government officials, but the battle's aftermath was pivotal in Church history.

This battle led to reports of a "Mormon insurrection" and the death of apostle David W. Patten. In consequence of these reports and the political influence of pro-slavery politicians, Missouri Governor Lilburn Boggs issued an executive order known as the "Extermination Order" on 27 October 1838. The order stated that the Mormon community was in "open and avowed defiance of the laws, and of having made war upon the people of this State ... the Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the State if necessary for the public peace—their outrages are beyond all description." [7][8] The Extermination Order was not officially rescinded until 1976 by Governor Christopher S. Bond.

Soon after the "Extermination Order" was issued, vigilantes attacked an outlying Mormon settlement and killed seventeen people. This event is identified as the Haun's Mill Massacre. Soon afterward, the 2,500 troops from the state militia converged on the Mormon headquarters at Far West. Smith and several other Church leaders surrendered to state authorities on charges of treason. Although they were civilians, the militia leader threatened to try Smith and others in a military tribunal and have them immediately executed. Were it not for the actions of General Alexander William Doniphan in defense of due process, the plans of the militia leaders likely would have been carried out.

The legality of Boggs' "Extermination Order" was debated in the legislature, but its objectives were achieved. Most of the Mormon community in Missouri had either left or been forced out by the spring of 1839.

Imprisonment

Instead of execution, Smith and others spent several months in Liberty Jail awaiting a trial that never came. With shaky legal grounds for imprisonment, guards, likely on the instructions of other authorities, eventually allowed their escape. They joined the rest of the Church in Illinois.

Life in Nauvoo, Illinois

After leaving Missouri in 1839, Smith and his followers made headquarters in a town called Commerce, Illinois on the banks of the Mississippi River, which they renamed Nauvoo (meaning "to be beautiful"; - the word is found in the Hebrew of Isaiah 52:7 - Latter Day Saints often referred to Nauvoo as "the city beautiful", or "the city of Joseph"—which was actually the name of the city for a short time after the city charter was revoked—or other similar nicknames) after being granted a charter by the state of Illinois. Nauvoo was quickly built up by the faithful, including many new arrivals.

In October 1839, Smith and others left for Washington, D.C. to meet with Martin Van Buren, then the President of the United States. Smith and his delegation sought redress for the persecution and loss of property suffered by the Saints in Missouri. Van Buren told Smith, "Your cause is just, but I can do nothing for you."

In 1840, the Illinois State Legislature passed a city-state charter for Nauvoo. On December 16 the governor signed it into law, granting Smith and the city of Nauvoo broad powers.

Work on a temple in Nauvoo began in the autumn of 1840. The cornerstones were laid during a conference on April 6, 1841. Construction took five years and it was dedicated on May 1, 1846; about four months after Nauvoo was abandoned by the majority of the citizens.

In March 1842, Smith was initiated as a Freemason (as an Entered Apprentice Mason on March 15, and Master Mason the next day—the usual month wait between degrees was waived by the Illinois Lodge Grandmaster, Abraham Jonas) at the Nauvoo Lodge, one of less than a half-dozen Masonic meetings he attended. He was introduced by John C. Bennett, a Mason from the northeast.

In February, 1844, Smith announced his candidacy for President of the United States, with Sidney Rigdon as his vice-presidential running mate.

Nauvoo's population peaked in 1845 when it may have had as many as 12,000 inhabitants (and several nearly-as-large suburbs) — rivaling Chicago, Illinois, whose 1845 population was about 15,000, and its suburbs.

Controversy in the City Beautiful

On the evening of May 6, 1842, a gunman shot through a window in Governor Boggs' home, hitting him four times. Sheriff J.H. Reynolds discovered a revolver at the scene, still loaded with buckshot and surmised that the suspect lost his firearm in the dark rainy night.

Some Saints saw the assassination attempt positively given Boggs' history of acting against the Church: an anonymous contributor to The Wasp, a Mormon newspaper in Nauvoo, wrote on May 28 that, "Boggs is undoubtedly killed according to report; but who did the noble deed remains to be found out."

Several doctors—including Boggs' brother—pronounced Boggs all but dead; at least one newspaper ran an obituary. To everyone's great surprise, Boggs not only survived, but gradually improved. The popular press—and popular rumor—was quick to blame Smith's friend and sometime bodyguard Porter Rockwell for the assassination attempt. By some reports, Smith had prophesied that Boggs would die violently, leading to speculation that Smith was involved. Rockwell denied involvement, stating that he would not have left the governor alive if he had indeed tried to kill him.

Also at about this time, Bennett had become disaffected from Smith and began publicizing what he said was Smith's practice of "Spiritual Wifery". (Bennett, earlier a pro-polygamy activist, knew of Smith's revelation on plural marriage and encouraged Smith to advocate the practice publicly. When this was rejected by Smith, Bennett began seducing women on his own and was subsequently excommunicated for practicing "Spiritual Wifery"[1]; which, incidentally, is not synonymous with plural marriage.) He stepped down as Nauvoo mayor—ostensibly in protest of Smith's actions—and also reported that Smith had offered a cash reward to anyone who would assassinate Boggs. He also reported that Smith had admitted to him that Rockwell had done the deed and that Rockwell had made a veiled threat on Bennett's life if he publicized the story. Smith vehemently denied Bennett's account, speculating that Boggs—no longer governor, but campaigning for state senate—was attacked by an election opponent. Bennett has been identified as "untruthful" by many historians and is seldom used as a reputable source.

Critics suggested that Nauvoo's charter should be revoked, and the Illinois legislature considered the notion. In response, Smith petitioned the U.S. Congress to make Nauvoo a territory. His petition was declined.

Kinderhook Plates

In April 1843, twelve men in Kinderhook, Pike County, Illinois, indicated they had found six small brass plates on the property of Robert Wiley. Wiley had indicated that he had dreamed on three consecutive nights of treasure being buried in a mound, which had caused the plates to be discovered. In reality, Wiley, W. Fugate, and a blacksmith named Whiddon had counterfeited the plates making the characters with an acid process.

A letter was sent to the Times and Seasons revealing the discovery. In addition, an editorial was published on May 3, 1843 in the Quincy Whig, another newspaper hostile to the Mormon people, baited Smith by proffering that "some pretend to say that Smith, the Mormon leader, has the ability to read them" and that "it would go to prove the authenticity of the Book of Mormon."

After a few weeks had passed the plates were brought to Joseph Smith to be translated. Several men presented themselves at Smith's home with the plates to determine if Joseph could translate them. Williard Richards records that Joseph sent William Smith for a Hebrew Bible and lexicon, seemingly in an attempt to translate the plates in a conventional process. William Clayton, in a conflicting account, wrote in his journal: "I have seen 6 brass plates... covered with ancient characters of language containing from 30 to 40 on each side of the plates. Prest J. has translated a portion and says they contain the history of the person with whom they were found and he was a descendant of Ham through the loins of Pharaoh king of Egypt, and that he received his kingdom from the ruler of heaven and earth."[citation needed]

After this initial meeting, no further mention was ever made by Joseph Smith regarding translation of these plates. Smith may not have sensed the fraud; however he never pursued their translation.(Bushman, Rough Stone Rolling, p. 490) Whiddon, Wiley, and Fugate never said anything further regarding their fraud until 1879, when one of the party signed an affidavit revealing their fabrication and their desire to ensare Smith.

The plates were lost in the Civil War but re-discovered by a Mormon scholar in the archives of the Chicago Historical Society Museum in the 1960's. Non-destructive tests were permitted to be done in 1965 by a Mormon Physicist, George M. Lawrence. In his report Lawrence wrote: The dimensions, tolerances, composition and workmanship are consistent with the facilities of an 1843 blacksmith shop and with the fraud stories of the original participants." This conclusion was not accepted by the Church at large and the original claim of Smith's translation persisted in Church books and publications until 1980 when conclusive tests were completed that determined the plates were made from a modern alloy.

Nauvoo Legion

Among the powers granted to the City of Nauvoo under its city charter was the authority to create a "body of independent militarymen." This force was a militia, and it became known as the "Nauvoo Legion". By 1842, the militia had 2,000 troops, and at least 3,000 by 1844, including some non-Mormons. In comparison, the U.S. Army had only 8,500 men in this period.

Although the charter authorizing the Nauvoo Legion created an independent militia, it could be used at the disposal of the state governor or the President of the United States as well as for the mayor of Nauvoo. Joseph Smith himself was Nauvoo's second mayor, and the Nauvoo court martial also appointed him as highest ranking officer of the Legion, a Lieutenant General. This rank is one step above Major General which most contemporary militias employed as their commanding rank. One motive for the higher rank was to prevent Smith from being tried in a court martial by officers of lesser rank. In 1837 the Missouri militia had contemplated an illegal court martial against Smith, only a civilian at that time.

In the last month of his life, June 1844, Smith declared martial law in Nauvoo and deployed the Legion to defend the city.

Smith's death

Several of Smith's disaffected associates at Nauvoo, Hancock County, Illinois—some of whom asserted that Smith had tried to seduce their wives into plural marriage—joined together to publish a newspaper called the Nauvoo Expositor. Its first and only issue was published 7 June 1844.

The paper was highly critical of Smith, expounding the beliefs that he had become a fallen prophet, held too much power as both mayor of Nauvoo and President of the Church, and that he was corrupting women through the practice of plural marriage. The publication of this material disturbed many of Nauvoo's citizens, and the city council responded by passing an ordinance declaring the newspaper a public nuisance designed to promote violence against Smith and his followers. Under the council's new ordinance, Smith, as Nauvoo's mayor, in conjunction with the city council, ordered the city marshal to destroy the paper and the press on June 10, 1844.

The legality of this action was challenged and many accused Smith of violating freedom of the press. Violent threats were made against Smith and the Mormon community. Thomas Sharp, editor of the Warsaw Signal, a newspaper hostile to the Mormons, editorialized:

- War and extermination is inevitable! Citizens ARISE, ONE and ALL!!!—Can you stand by, and suffer such INFERNAL DEVILS! To ROB men of their property and RIGHTS, without avenging them. We have no time for comment, every man will make his own. LET IT BE MADE WITH POWDER AND BALL!!! (Warsaw Signal, 12 June 1844, p. 2.)

Charges were brought against Smith and he submitted to incarceration in Carthage, the county seat. Smith's brother, Hyrum, and several friends, including John Taylor and Willard Richards, accompanied him to the jail.

After a hearing, Smith was released but stayed in the jail at the request of Govenor Dunklin as there were to be additional charges filed the following day. According to Taylor and Richards, Dunklin promised to take Smith back to Nauvoo; however, he left Carthage without him. At about 5:00 p.m. on June 27, 1844, a mob of about 200 armed men stormed Carthage Jail. The mob shot and killed Smith and his brother Hyrum, and wounded John Taylor.

Plural marriage

- See also: Joseph Smith, Jr. and Polygamy for a possible list of Smith's alleged plural wives.

Most believe that Smith began practicing a form of polygyny called "celestial marriage" (later called plural marriage) perhaps as early as 1833. Polygamy (marriage to multiple partners) was illegal in many U.S. States, including Illinois, and was felt by some to be an immoral or misguided practice.

Records indicate that Smith and a small number of followers practiced plural marriage during the later years of his life. Joseph's wife Emma was at times ambivalent and at times hostile to the practice. Sources indicate that Joseph concealed at least some of his plural marriages from her. However, she assented to others at various times, and stood as a witness in some of the weddings. After Smith's death, Emma stated publicly that he had never practiced plural marriage, and her son Joseph Smith III believed that Brigham Young introduced the practice.

There is disagreement as to the precise number of wives Smith may have had. One historian, Todd M. Compton, who contends that polygamy was a mistake for the Church, tried to document, using Utah LDS sources, at least thirty-three plural marriages or sealings during Smith's lifetime. It is without question that Smith had multiple wives (as marriage certificates are available for some); but, as Compton states multiple times in his work "[a]bsolutely nothing is known of this marriage after the ceremony"; that is, it is unclear how many (if any) of these marriages Smith consummated. Information on the intention of some of the sealings is similarly ambiguous; Smith has been sealed to many people, male and female, as a father or a brother with no marital intention or obligation.

If these marriage sealings were indeed sexual unions, it would be reasonable to expect some children from them as there were from Smith's marriage to Emma. One of the plural wives made an allegation that Smith had fathered one of her children, but this is disputed, as is the theory that Smith fathered children with some of his plural wives that were raised as though they were the children of their other husbands. Dr. Scott Woodward and others are conducting DNA evidence of possible descendants of Smith. To date, none of these plural marriages has been shown to have produced genetic offspring of Smith [3].

The LDS Church believes that polygamy was instituted according to revelation from God to Smith, claiming parity with the practices of Old Testament figures (e.g. Jacob, David, and Solomon). The LDS Church publicly announced the practice in Utah in 1852, after which the doctrine was generally accepted, but not widely practiced. Plural marriage was later formally discontinued by the LDS Church (new plural marriages were banned by the Church following a revelation to President Wilford Woodruff in 1890), and the Church currently excommunicates members who practice it. The Community of Christ (formerly Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints) denied for many years that Smith ever taught or practiced polygamy. More recently, some Community of Christ historians have publicly supported the view that Smith taught the doctrine, though many within the RLDS movement continue to claim otherwise. Many splinter groups of the Latter Day Saint Movement descended from the LDS Church continue to practice plural marriage.

Notes

- ^ Covenant 115:3

- ^ Covenant 37

- ^ Covenant 57

- ^ Covenant 103

- ^ Covenant 57:3

- ^ Lindsay, Jeff. "Quick Answer: Who Were the Danites?". LDS FAQ. Retrieved August 22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Extermination Order". LDS FAQ. Retrieved August 22.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Boggs, Extermination Order