Impeachment

Impeachment is the process by which a legislative body formally levels charges against a high official of government. Impeachment does not necessarily mean removal from office; it comprises only a formal statement of charges, akin to an indictment in criminal law, and thus forms only the first step towards removal. Once an individual is impeached, he or she must then face the possibility of conviction via legislative vote, which then entails the removal of the individual from office.

Because impeachment and conviction of officials involves an overturning of the normal constitutional procedures by which individuals achieve high office (election, ratification, or appointment) and because it generally requires a supermajority, usually only those deemed to have committed serious abuses of their office may suffer impeachment.

One tradition of impeachment has its origins in the law of England, where the procedure last took place in 1806. Impeachment exists under constitutional law in many nations around the world, including the United States, Russia, the Philippines and the Republic of Ireland.

United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, the House of Commons holds the power of impeachment: it draws up charges as "Articles of Impeachment," each article detailing a separate allegation. The Commons appoints managers, who act as prosecutors in the trial. The mover of the impeachment must go to the House of Lords and then declare the impeachment of the defendant "in the name of the House of Commons, and all the Commons of the United Kingdom."

The House of Lords hears the case, with the Lord Chancellor (or the Lord High Steward if the impeachment relates to a peer) presiding. The hearing resembles an ordinary trial: both sides may call witnesses and present evidence. At the end of the hearing the Lord Chancellor puts the question on the first article to each member in order of seniority, commencing with the most junior peer, and ending with himself, and after all have voted, proceeds to deal with any remaining articles similarly. Upon being called, a Lord must rise and declare upon his honour, "Guilty" or "Not Guilty". After voting on all of the articles has taken place, and if the Lords find the defendant guilty, the Commons may move for judgment; the Lords may not declare the punishment until the Commons have so moved. The Lords may then provide whatever punishment they find fit, within the law. A Royal Pardon cannot excuse the defendant from trial, but a Pardon may reprieve a convicted defendant.

Parliament has held the power of impeachment since mediæval times. Originally, the House of Lords held that impeachment could only apply to members of the peerage (nobles), as the nobility (the Lords) would try their own peers, while commoners ought to try their peers (other commoners) in a jury. However, in 1681, the Commons declared that they had the right to impeach whomsoever they pleased, and the Lords have respected this resolution.

After the reign of Edward IV, impeachment fell into disuse, the bill of attainder becoming the preferred form of dealing with undesirable subjects of the Crown. However, during the reign of James I and thereafter, impeachments became more popular, as they did not require the assent of the Crown, while bills of attainder did, thus allowing Parliament to resist royal attempts to dominate Parliament. The procedure has, over time, fallen into disuse. The principles of "responsible government" require that the Prime Minister and other executive officers answer to Parliament, rather than to the Sovereign. Thus, if the Commons wished, they could easily cause the removal of such an officer without a long, drawn-out impeachment. The last two cases of impeachment dealt with Warren Hastings, Governor-General of India between 1789 and 1795, and Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, First Lord of the Admiralty, in 1806. The last attempted impeachment was in 1848, when David Urqhart accused Viscount Palmerston of having signed a secret treaty with Imperial Russia and of being in the pay of the Tsar. Palmerston survived the vote in the Commons and no case was heard in the Lords.

On 25 August 2004, Plaid Cymru MP Adam Price announced his intention to move an impeachment against Tony Blair. Price has the public backing of all Welsh and Scottish nationalist MPs, and claims to have received tacit support from a number of Labour backbenchers. In addition, the editor of the Spectator, Conservative MP Boris Johnson, has expressed his support for the impeachment of Blair.

United States

In the United States impeachment at the Federal level can apply only to those who may have committed "high crimes and misdemeanors". In the case of the President, Vice President, and other executive officers, removal takes place automatically upon conviction. Successful impeachment does not, however, automatically remove judges.

The federal procedure in the United States involves a vote for impeachment in the House of Representatives on Articles of Impeachment, as in the United Kingdom. Those voting in favour of impeachment may then vote to appoint managers. The hearing takes place in the Senate. In the case of the impeachment of a President, the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court presides over the proceedings. Otherwise, the Vice President, in his capacity of President of the Senate, or otherwise the President pro tempore of the Senate (Temporary President) presides.

The proceedings unfold, as in the United Kingdom, in the form of a trial, with each side having the right to call witnesses and perform cross-examinations. Senators must also take an oath or affirmation that they will perform their duties honestly and with due diligence, as opposed to the British Lords, who vote upon their honour. The hearing requires a simple majority of the Senators as a quorum. After the hearing the deliberations take place in private. Conviction requires a two-thirds majority. The Senate may vote thereafter to punish the individual only by removing him from office, or by barring him from holding future office, or both. Alternatively, it may impose no punishment. But in the case of executive officers, removal follows automatically upon conviction. The defendant remains liable to criminal prosecution. The President may not in any case use his power of pardon during impeachment, but may, as usual, pardon a defendant in the case of a criminal prosecution.

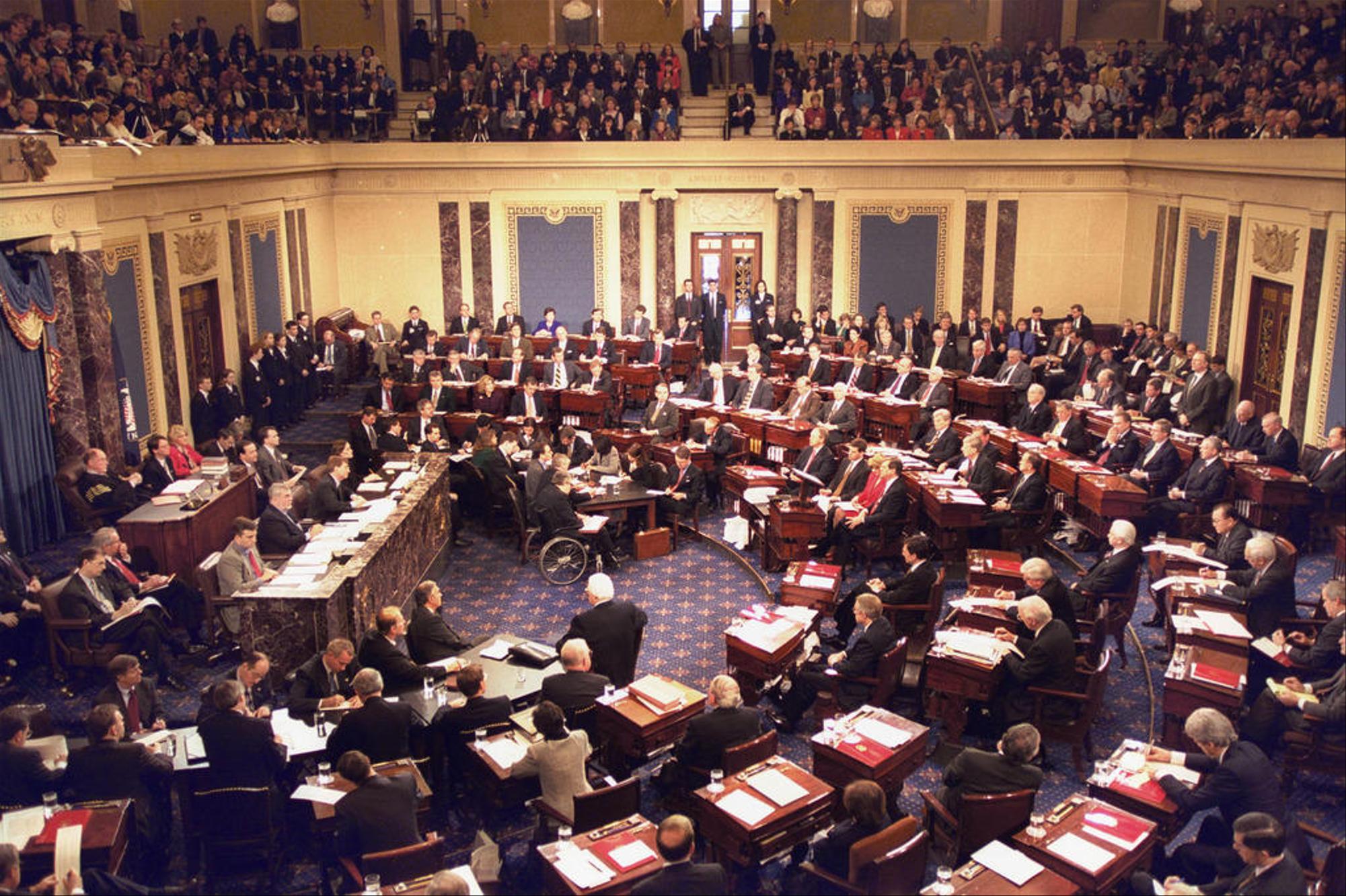

The impeachment trial of Bill Clinton (1999): William H. Rehnquist

presides. The House managers sit beside the quarter-circular tables on the left;

the President's personal counsel sits on the right.

Congress regards impeachment as a power to use only in extreme cases; the House has initiated impeachment proceedings only sixty-two times since 1789. Impeachments of only seventeen federal officers have taken place:

- two presidents: Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton, both acquitted. (Richard Nixon resigned after impeachment hearings against him started.)

- one cabinet officer

- one senator

- thirteen federal judges.

The impeachment of the Senator, William Blount, stalled on the grounds that legislators did not qualify as civil officers of the United States. Of the remaining cases, two did not come to trial trial because the individuals had left office; seven ended in acquittal, and seven in conviction. Each of the seven Senate convictions has involved a federal judge.

Impeachment can also occur in the United States at the state level. State legislatures can impeach state officials, including governors. Impeachment and removal of governors has happened occasionally throughout the history of the United States, usually for corruption charges. There have been seven state governor impeachments in all. As of 2004 the most recent impeachment took place in Arizona and resulted in the removal of Gov. Fife Symington in September 1997.

Republic of Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland formal impeachment can apply only to the President. Article 12 of the Constitution of Ireland provides that, unless judged to be "permanently incapacitated" by the Supreme Court, the President can only be removed from office by the houses of the Oireachtas (parliament) and only for the commission of "stated misbehaviour". Either house of the Oireachtas may impeach the President, but only by a resolution approved by a majority of at least two-thirds of its total number of members; and a house may not consider a proposal for impeachment unless requested to do so by at least thirty of its number.

Where one house impeaches the President, the remaining house either investigates the charge or commissions another body or committee to do so. The investigating house can remove the President if it decides, by at least a two-thirds majority of its members, that she is guilty of the charge of which she stands accused, and that the charge is sufficiently serious as to warrant her removal. To date no impeachment of an Irish President has ever taken place. The President holds a largely ceremonial office, the dignity of which is considered important, so it is likely that a president would resign from office long before undergoing formal conviction or impeachment.

The Republic's constitution and law also provide that only the foot of a joint resolution of both houses of the Oireachtas may remove a judge. Although often referred to as the 'impeachment' of a judge, this procedure does not technically involve impeachment.

Other nations

- Carlos Andrés Pérez, president of Venezuela, underwent impeachment in 1993.

- Rolandas Paksas, the president of Lithuania, sufferred impeachment on April 6, 2004.

- The impeachment of Roh Moo-hyun, the president of South Korea, took place on March 12, 2004; Korea's Constitutional Court overturned the decision on May 14, 2004.