Turtle

| Turtles Temporal range: Triassic - Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

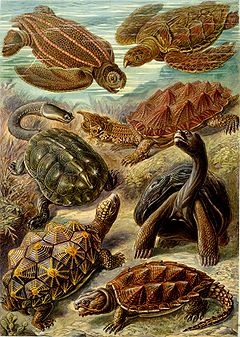

| "Chelonia" from Ernst Haeckel's Artforms of Nature, 1904 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | Testudines Linnaeus, 1758

|

| Suborders | |

|

Cryptodira | |

Turtles are reptiles of the order Testudines (all living turtles belong to the crown group Chelonia), most of whose body is shielded by a special bony or cartilagenous shell developed from their ribs. The order of Testudines includes both extant (living) and extinct species, the earliest turtles being known from the early Triassic Period, making them one of the oldest reptile groups, and a much more ancient group than the lizards and snakes. About 300 species are alive today. Some species of turtles are highly endangered.

Turtle, terrapin, or tortoise?

In British English it is normal to describe these reptiles as turtles, terrapins, or tortoises, depending on whether they live in the sea, in fresh water, or on land. Thus the green sea turtle, Chelonia mydas, is considered a turtle; the red-eared slider, Trachemys scripta elegans, a terrapin; and the eastern box turtle, Terrapene carolina carolina, a tortoise.

In American English it is common to call them turtles regardless of habitat, although tortoise is sometimes used as a more precise term for the land-dwelling species. Ocean-going species are sea turtles. Terrapin is reserved for the diamondback terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin, though even that species is often simply referred to as a turtle. Incidentally, the word terrapin itself comes from the Native American (Algonquian) name of this animal [1].

Speakers of Australian English tend to use turtle for both marine and freshwater species and tortoise for the terrestrial species.

The word chelonian is increasingly popular among veterinarians, scientists, and conservationists working with these animals. It is based on the Greek word χελώνα( /çeˈlona/, chelone), meaning tortoise, and is used, for example, by the Chelonian Research Foundation.

Evolution

The first turtles are believed to have existed in the Mesozoic, around 200 million years ago. Their exact ancestry is disputed. It was believed that they are the only surviving branch of the ancient clade Anapsida, which includes groups such as procolophonoids, millerettids, protorothyrids and pareiasaurs. All anapsid skulls lack a temporal opening, while all other extant amniotes have temporal openings (although in mammals the hole has become the zygomatic arch). Most anapsids became extinct in the late Permian period, except procolophonoids and possibly the precursors of the testudines (turtles).

However, it was recently suggested that the anapsid-like turtle skull may be due to reversion rather than to anapsid descent. More recent phylogenetic studies with this in mind placed turtles firmly within diapsids, slightly closer to Squamata than to Archosauria. All molecular studies have strongly upheld this new phylogeny, though some place turtles closer to Archosauria. Re-analysis of prior phylogenies suggests that they classified turtles as anapsids both because they assumed this classification (most of them studying what sort of anapsid turtles are) and because they did not sample fossil and extant taxa broadly enough for constructing the cladogram. While the issue is far from resolved, most scientists now lean towards a diapsid origin for turtles.

Physical Description

Turtles vary widely in size, although marine turtles tend to be relatively big animals. The largest chelonian is a marine turtle, the great leatherback sea turtle, which can reach a shell length of 200 cm (72 in) and can reach a weight of over 750 kg (2,000 lb, or 1 ton). Freshwater turtles are smaller, with the largest species being the Asian softshell turtle Pelochelys cantorii, which has been reported to measure up to 200 cm or 80 inches (Das, 1991). This dwarfs even the better-known alligator snapping turtle, the largest chelonian in North America, which attains a shell length of up to 80 cm (31.5 in) and a weight of about 76 kg (170 lb). Giant tortoises of the genera Geochelone, Meiolania, and others were relatively widely distributed around the world into prehistoric times, and are known to have existed in North and South America, Australia, and Africa. They became extinct at the same time as the appearance of Man, and it is assumed that humans hunted them for food. The only surviving giant tortoises are on the Seychelles and Galápagos Islands and can grow to over 130 cm (50 in) in length, and weigh about 300 kg (670 lb) [2].

The largest ever chelonian was Archelon ischyros, a Late Cretaceous sea turtle known to have been up to 4.6 m (15 ft) long [3].

The smallest turtle is the speckled padloper tortoise of South Africa. It measures no more than 8 cm (3 in) in length and weighs about 140 g (5 oz). Two other species of small turtles are the American mud turtles and musk turtles that live in an area that ranges from Canada to South America. The shell length of many species in this group is less than 13 cm (5 in) in length.

Shell

The upper shell of the turtle is called the carapace. The lower shell that incases the belly is called the plastron. The carapace and plastron are joined together on the turtle's sides by bony structures called bridges. The inner layer of a turtle's shell is made up of about 60 bones that includes portions of the backbone and the ribs, meaning the turtle can not crawl out of its shell. In most turtles, the outer layer of the shell is covered by horny scales called scutes that are part of its outer skin, or epidermis. Scutes are made up of a fiberous protein called keratin that also makes up the scales of other reptiles. These scutes overlap the seams between the shell bones and add strength to the shell. Some turtles do not have horny scutes. For example, the leatherback sea turtle and the soft-shelled turtles have shells covered with leathery skin instead.

The shape of the shell gives helpful clues to how the turtle lives. Most tortoises have a large domed-shaped shell that makes it difficult for predators to crush them between their jaws. One of the few exceptions is the African pancake tortoise which has a flat, flexible shell that allows it to hide in rock crevices. Most aquatic turtles have flat, streamlined shells that aid with swimming and diving. American snapping turtles and musk turtles have small, cross-shaped plastrons that give the turtle more efficient leg movement for walking along the bottom of ponds and streams.

Tortoises have rather heavy shells in constrast to aquatic and soft-shelled turtles that have lighter shells that help them avoid sinking in the water and swim faster and more agile. These light shells have large spaces called fontanelles between the shell bones. The shell of a leatherback turtle is extremely light because they lack scutes and contain many fontanelles. The color of a turtle's shell may vary. Shells are commonly coloured brown, black, or olive green. In some species, shells may have red, orange, yellow, or grey markings and these markings are often spots, lines, or irregular blotches. One of the most colorful turtles is the eastern painted turtle which includes a yellow plastron and a black or olive shell with red markings around the rim.

Skin and Moulting

As mentioned above, the outer layer of the shell is part of the skin, each scute (or plate) on the shell corresponding to a single modified scale. The remainder of the skin is composed of skin with much smaller scales, similar to the skin of other reptiles. Turtles and terrapins do not moult their skins all in one go, as snakes do, but continuously, in small pieces. When kept in aquaria, small sheets of dead skin can be seen in the water, having been sloughed off, often when the animal deliberately rubs itself against a piece of wood or stone. Tortoises also shed skin, but a lot of dead skin is allowed to accumulate into thick knobs and plates that provide protection to parts of the body outside the shell.

The scutes on the shell are never moulted, and as they accumulate over time, the shell becomes thicker. By counting the rings formed by the stack of smaller, older scutes on top of the larger, newer ones, it is possible to estimate the age of a turtle, if you know how many scutes are produce in a year [4]. This method is not very accurate, partly because growth rate is not constant, but also because some of the scutes on the shell eventually fall away from the shell.

Head

Most turtles and tortoises have eyes placed on the upper sides of their heads. Species of turtles that spend most of their life on land have their eyes looking down at objects in front of them. Some aquatic turtles, such as snapping turtles and soft-shelled turtles, have eyes closer to the top of the head. These species of turtles can hide from predators in shallow water where they lie entirely submerged except for their eyes and nostrils. Sea turtles possess glands near their eyes that produce salty tears that rids their body of excess salt taken in from the water they drink.

Turtles use their jaws to cut and chew food. Instead of teeth, the upper and lower jaws of the turtle are covered by horny ridges. Carnivorous turtles usually have knife-sharp ridges for slicing through their prey. Herbivourous turtles have serrated edged ridges that help them cut through tough plants. Turtles use their tongues to swallow food, but they can't, unlike most reptiles, stick out their tongues to catch food.

Limbs

The fully terrestrial tortoises have short, sturdy feet. Tortoises are famous for moving slowly, in part because of their heavy shell but also because of the relatively inefficient sprawling gait that they have, with the legs being bent, as with lizards rather than being straight and directly under the body, as is the case with mammals.

The amphibious terrapins normally have limbs similar to those of tortoises except that the feet are webbed and often have long claws. These terrapins swim using all four feet in a way similar to the doggy paddle, with the feet on the left and right side of the body alternately providing thrust. Large terrapins tend to swim less than smaller ones, and the very big species, such as aligator snapping turtles, hardly swim at all, preferring to simply walk along the bottom of the river or lake. As well as webbed feet, terrapins also have very long claws, used to help them clamber onto riverbanks and floating logs, upon which they like to bask. Male terrapins tend to have particularly long claws, and these appear to be used to stimulate the female while mating. While most terrapins have webbed feet, a few terrapins, such as the pig-nose turtles, have true flippers, with the digits being fused into paddles and the claws being relatively small. These species swim in the same way as sea turtles (see below).

Sea turtles are entirely aquatic and instead of feet they have flippers. Sea turtles "fly" through the water, using the an up-and-down motion of the front flippers to generate thrust; the back feet are not used for propulsion but may be used as rudders for steering. Compared with terrapins, sea turtles have very limited mobility on land, and apart from the dash from the nest to the sea as hatchlings, male sea turtles normally never leave the sea. Females must come back onto land to lay eggs. They move very slowly and laboriously, dragging themselves forwards with their flippers. The back flippers are used to dig the burrow and then fill it back with sand once the eggs have been deposited.

Order Testudines - Turtles

Suborder Paracryptodira (extinct)

Suborder Cryptodira

- Family Chelydridae (Snapping Turtles)

- Superfamily Testudinoidae

- Family Haichemydidae (extinct)

- Family Sinochelyidae (extinct)

- Family Lindholmemydidae (extinct)

- Family Testudinidae (Tortoises)

- Family Geoemydidae (Asian River Turtles, Leaf and Roofed Turtles, Asian Box Turtles)

- Family Emydidae (Pond Turtles/Box and Water Turtles)

- Superfamily Trionychoidae

- Family Adocidae (extinct)

- Family Carettochelyidae (Pignose Turtles)

- Family Trionychidae (Softshell Turtles)

- Superfamily Kinosternoidae

- Family Dermatemydidae (River Turtles)

- Family Kinosternidae (Mud and Musk Turtles)

- Family Platysternidae (Big-headed Turtles)

- Superfamily Chelonioidae (Sea Turtles)

- Family Toxochelyidae (extinct)

- Family Cheloniidae (Green Sea Turtles and relatives)

- Family Thalassemyidae (extinct)

- Family Dermochelyidae (Leatherback Turtles)

- Family Protostegidae (extinct)

Suborder Pleurodira

- Family Proterochersidae (extinct)

- Family Chelidae (Austro-American Sideneck Turtles)

- Family Araripemydidae (extinct)

- Superfamily Pelomedusoidae

- Family Pelomedusidae (Afro-American Sideneck Turtles)

- Family Bothremydidae (extinct)

- Family Podocnemididae (Madagascan Big-headed and American Sideneck River Turtles)

See also

- Jackson ratio

- Tortoise - the terrestrial version of the turtles.

- Turtle racing

- Turtles and tortoises in popular culture

- Turtles all the way down

External links

- A description of turtles' adaptations

- Internationale Schildkröten Vereinigung - German language page

- UC Berkeley Museum of Paleontology

- Turtle Trax: Excellent marine turtle site

- California Turtle and Tortoise Club: Informative and entertaining in equal measure

- Turtles Zone: Resource site for information on the captive care of turtles.

- Turtle Times: A turtle search engine.

- Gulf Coast Turtle and Tortoise Society: Care Information, Species Descriptions, and More.

- Turtles of the World: Extensive information on all known turtles, tortoises and terrapins, including key and quiz.

- Chelonia: Conservation and Care of Turtles.

- Internationale Schildkröten Vereinigung - German language page

- UC Berkeley Museum of Paleontology

- Turtle Trax: Excellent marine turtle site

- California Turtle and Tortoise Club: Informative and entertaining in equal measure

- Turtles Zone: Resource site for information on the captive care of turtles.

- Turtle Times: A turtle search engine.

- Gulf Coast Turtle and Tortoise Society: Care Information, Species Descriptions, and More.

- Turtles of the World: Extensive information on all known turtles, tortoises and terrapins, including key and quiz.

- Chelonia: Conservation and Care of Turtles.