Roche limit

|

|

|

|

|

The Roche limit, sometimes referred to as the Roche radius, is the distance within which a celestial body held together only by its own gravity will disintegrate due to a second celestial body's tidal forces exceeding the first body's gravitational self-attraction. Inside the Roche limit, orbiting material will tend to disperse and form rings, while outside the limit, material will tend to coalesce. The term is named after Édouard Roche, the French astronomer who first calculated this theoretical limit in 1848.

The Roche limit should not be confused with the concept of the Roche lobe, which is also named after Édouard Roche. The Roche lobe describes the limits at which an object which is in orbit around two other objects will be captured by one or the other.

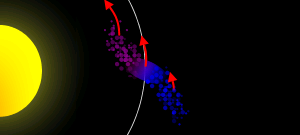

Typically, the Roche limit applies to a satellite disintegrating due to tidal forces induced by its primary, the body about which it orbits. Some real satellites, both natural and artificial, can orbit within their Roche limits because they are held together by forces other than gravitation. Jupiter's moon Metis and Saturn's moon Pan are examples of natural satellites which are able to hold together despite being within their fluid Roche limits. They hold together partly because of their tensile strength, and partly because they are not actually fluid. In such cases, it is possible for an object resting on the surface of such a satellite to be pulled away by tidal forces, depending on where it is: tidal forces are most repulsive along the line of centers between the satellite and primary. A weaker satellite, such as a comet, could be broken up when it passes within its Roche limit. Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9's decaying orbit around Jupiter passed within its Roche limit in July 1992, causing it to fragment into a number of smaller pieces. On its next approach in 1994 the fragments crashed into the planet.

Since tidal forces overwhelm gravity within the Roche limit, no large satellite can coalesce out of smaller particles within that limit. Indeed, almost all known planetary rings are located within their Roche limit (Saturn's E-Ring being a notable exception). They could either be remnants from the planet's proto-planetary accretion disc that failed to coalesce into moonlets, or conversely have formed when a moon passed within its Roche limit and broke apart.

Determining the Roche limit

The Roche limit depends on the rigidity and density of the satellite. A rigid satellite is one extreme, and will maintain its shape until tidal forces break it apart. At the other extreme, a highly fluid satellite gradually deforms leading to increased tidal forces, and eventually breaks apart.

To calculate the "rigid body" Roche limit for a spherical satellite, the cause of the rigidity is neglected but it is assumed that it does not deform from its spherical shape while being held together only by its own self-gravity. Other effects are also neglected, such as tidal deformation of the primary, rotation of the satellite, and its irregular shape. The Roche limit, , is then the following:

where is the primary's radius, is the primary's density and is the satellite's density.

For a fluid satellite, tidal forces cause the satellite to elongate, further compounding the tidal forces and causing it to break apart more readily. The calculation is complex and its result cannot be expressed as an algebraic formula, but a close approximation is the following:

which indicates that a fluid satellite will disintegrate at almost twice the distance from the primary as a rigid sphere of similar density.

Most real satellites are somewhere between these two extremes, with internal friction, viscosity, and tensile strength rendering the satellite neither perfectly rigid nor perfectly fluid.

Rigid satellites

As stated above, the formula for calculating the Roche limit, , for a rigid spherical satellite orbiting a spherical primary is:

where is the radius of the primary, is the density of the primary, and is the density of the satellite. As described below, this rigid-body approximation does not take into account the deformation of the satellite's spherical shape due to tidal effects and is only an approximation of what a real satellite's Roche limit would be.

Notice that if the satellite is more than twice as dense as the primary (as can easily be the case for a rocky moon orbiting a gas giant) then the Roche limit will be inside the primary and hence not relevant.

Derivation of the formula

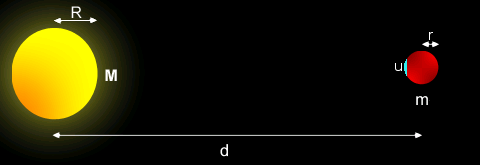

In order to determine the Roche limit, we consider a small mass on the surface of the satellite closest to the primary. There are two forces on this mass : the gravitational pull towards the satellite and the gravitational pull towards the primary. Since the satellite is already in orbital free fall around the primary, the tidal force is the only relevant term of the gravitational attraction of the primary.

The gravitational pull on the mass towards the satellite with mass and radius can be expressed according to Newton's law of gravitation.

The tidal force on the mass towards the primary with radius and a distance between the centers of the two bodies can be expressed as:

The Roche limit is reached when the gravitational pull and the tidal force cancel each other out.

or

Which quickly gives the Roche limit, , as:

However, we don't really want the radius of the satellite to appear in the expression for the limit, so we re-write this in terms of densities.

For a sphere the mass can be written as:

- where is the radius of the primary.

And likewise:

- where is the radius of the satellite.

Substituting for the masses in the equation for the Roche limit, and cancelling out gives:

which can be simplified to the Roche limit:

Fluid satellites

A more accurate approach for calculating the Roche Limit takes the deformation of the satellite into account. An extreme example would be a tidally locked liquid satellite orbiting a planet, where any force acting upon the satellite would deform it (into a prolate spheroid).

The calculation is complex and its result cannot be represented as an algebraic formula. Historically, Roche himself derived the following numerical solution for the Roche Limit:

However, a better approximation that takes into account the primary's oblateness and the satellite's mass is:

where is the oblateness of the primary. The numerical factor is calculated with the aid of a computer.

Roche limits for selected examples

The table below shows the mean density and the equatorial radius for selected objects in our solar system.

| Primary | Density (kg/m3) | Radius (m) |

|---|---|---|

| Sun | 1,408 | 696,000,000 |

| Jupiter | 1,326 | 71,492,000 |

| Earth | 5,513 | 6,378,137 |

| Moon | 3,346 | 1,738,100 |

| Saturn | 0,6873 | 60,268,000 |

| Uranus | 1,318 | 25,559,000 |

| Neptune | 1,638 | 24,764,000 |

Using these data, the Roche Limits for rigid and fluid bodies can easily be calculated. The average density of comets is taken to be around 500 kg/m3.

The table below gives the Roche limits expressed in metres and in primary radii. The true Roche Limit for a satellite depends on its density and rigidity.

| Body | Satellite | Roche limit (rigid) | Roche limit (fluid) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance (km) | R | Distance (km) | R | ||

| Earth | Moon | 9,496 | 1.49 | 18,261 | 2.86 |

| Earth | average Comet | 17,880 | 2.80 | 34,390 | 5.39 |

| Sun | Earth | 554,400 | 0.80 | 1,066,300 | 1.53 |

| Sun | Jupiter | 890,700 | 1.28 | 1,713,000 | 2.46 |

| Sun | Moon | 655,300 | 0.94 | 1,260,300 | 1.81 |

| Sun | average Comet | 1,234,000 | 1.78 | 2,374,000 | 3.42 |

If the primary is less than half as dense as the satellite, the rigid-body Roche Limit is less than the primary's radius, and the two bodies may collide before the Roche limit is reached.

How close are the solar system's moons to their Roche limits? The table below gives each inner satellite's orbital radius divided by its own Roche radius. Both rigid and fluid body calculations are given. Note Naiad in particular, which may in fact be quite close to its actual break-up point.

In practice, the densities of most of the inner satellites of giant planets are not known. In these cases (shown in italics), likely values have been assumed, but their actual Roche limit can vary from the value shown.

| Primary | Satellite | Orbital Radius vs. Roche limit | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (rigid) | (fluid) | ||

| Sun | Mercury | 104:1 | 54:1 |

| Earth | Moon | 41:1 | 21:1 |

| Mars | Phobos | 172% | 89% |

| Deimos | 451% | 234% | |

| Jupiter | Metis | ~186% | ~94% |

| Adrastea | ~188% | ~95% | |

| Amalthea | 175% | 88% | |

| Thebe | 254% | 128% | |

| Saturn | Pan | 168% | 84% |

| Atlas | 176% | 88% | |

| Daphnis | ? | ? | |

| Prometheus | 178% | 89% | |

| Pandora | 178% | 89% | |

| Epimetheus | 192% | 95% | |

| Janus | 196% | 98% | |

| Uranus | Cordelia | ~154% | ~79% |

| Ophelia | ~166% | ~86% | |

| Bianca | ~183% | ~94% | |

| Cressida | ~191% | ~98% | |

| Desdemona | ~194% | ~100% | |

| Juliet | ~199% | ~102% | |

| Neptune | Naiad | ~139% | ~72% |

| Thalassa | ~149% | ~77% | |

| Despina | ~152% | ~78% | |

| Galatea | ~183% | ~94% | |

| Larissa | ~218% | ~113% | |

| Pluto | Charon | 12.5:1 | 6.5:1 |

See also

- Hill sphere

- Roche lobe

- Spaghettification (a rather extreme tidal distortion)

References

- Édouard Roche: La figure d'une masse fluide soumise à l'attraction d'un point éloigné, Acad. des sciences de Montpellier, Vol. 1 (1847-50) p. 243