Milice

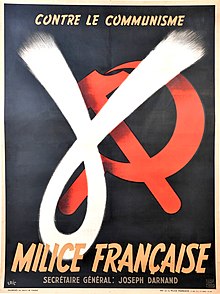

The Milice ("militia"), also known as the French Gestapo, was a paramilitary force created in 1943 to help fight "terrorism" in Vichy France – that is to say, to fight against the French Resistance. The Milice, headed by Joseph Darnand, participated in summary executions, assassinations and helped round up the Jews and resistants in France for deportation.

Like the Gestapo, the Milice often resorted to torture to extract information or confessions from those they rounded up. They were often considered even more deadly than the Gestapo and SS themselves, since they were Frenchmen who spoke the language, had a full knowledge of the towns and land, and knew people and informers.

Milice troops, known as miliciens, wore a brown uniform and a wide beret. (During active paramilitary-style operations, a pre-war French Army helmet was used.) Its newspaper was Combats. (Not to be confused with the underground Resistance newspaper, Combat.) The Resistance targeted individual miliciens for assassination, often in open areas such as cafes and public streets, scoring their first success on April 24, 1943, when they gunned down Marseilles milicien Paul de Gassovski. By late November, Combats reported that 25 miliciens had been killed and 27 wounded in Resistance attacks. The Milice retaliated by murdering several well-known left-wing politicians and intellectuals, such as Georges Mandel and Victor Basch.

Early volunteers for the Milice included members of France's pre-war far right-wing parties, such as Action Francaise, as well as fanatical Catholics eager to exact revenge on leftist and republican elements for the Dreyfus Affair. In addition to ideology, incentives for joining the Milice included employment, regular pay and rations. (The latter was particularly important as the war went on and civilian rations were reduced steadily to almost starvation levels.) Volunteers for the Milice were also exempt from being forcibly sent to Germany as slave laborers.

Confined initially to the former Zone Libre under the control of the Vichy regime, the Milice in January 1944 moved into what had been the Occupied Zone of France, including Paris. They established their headquarters in the old Communist Party headquarters at 44, rue Le Peletier, as well as 61, rue Monceau, in a house formerly owned by the Menier family, makers of France's best-known chocolates. The Lycee Louis-Le-Grand was occupied as a barracks. An officer candidate school was established, likely with intentional irony, in the Auteuil synagogue.

Perhaps the largest and best-known operation by the Milice was its attempt in March 1944 to suppress the Resistance in the departement of Haute-Savoie in the southeast of France near the Swiss border. The efforts of the Milice proved insufficient, however, and German troops had to be called in to complete the operation.

The organization reached a strength of about 35,000 by the time of the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944, but began melting away rapidly thereafter. Following the Liberation, those of its members who failed to make good their escape to Germany or elsewhere abroad generally faced either execution following summary courts martial or were simply shot out of hand by vengeful resistants and civilians. Paul Touvier, who led the Milice in Lyons, was convicted in 1994 of crimes against humanity and died in prison.

Since the Second World War, the term milice has acquired a derogatory meaning in French.