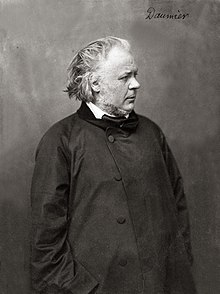

Honoré Daumier

Honoré Daumier (February 26, 1808 – February 10, 1879), was a French caricaturist, painter, sculptor, and one of the most gifted and prolific draftsmen of his time.

Early life

Born in Marseille, Daumier showed in his youth an irresistible inclination towards the artistic profession, which his father vainly tried to check by placing him first with a huissier, and later, with a bookseller. Having mastered the techniques of lithography, Daumier began his artistic career by producing plates for music publishers, and illustrations for advertisements. This was followed by anonymous work for publishers, in which he emulated the style of Charlet and displayed considerable enthusiasm for the Napoleonic legend.

Published works

When, during the reign of Louis Philippe, Charles Philipon launched the comic journal, La Caricature, Daumier joined its staff, which included such powerful artists as Devéria, Raffet and Grandville, and started upon his pictorial campaign of satire, targeting the foibles of the bourgeoisie, the corruption of the law and the incompetence of a blundering government. His caricature of the king as Gargantua led to Daumier's imprisonment for six months at Ste Pelagic in 1832. Soon after, the publication of La Caricature was discontinued, but Philipon provided a new field for Daumier's activity when he founded the Le Charivari.

Daumier produced his social caricatures for Le Charivari, in which he held bourgeois society up to ridicule in the figure of Robert Macaire, hero of a popular melodrama. In another series, L'histoire ancienne, he took aim at the constraining pseudo-classicism of the art of the period. In 1848 Daumier embarked again on his political campaign, still in the service of Le Charivari, which he left in 1860 and rejoined in 1864.

Paintings

In addition to his prodigious activity in the field of caricature — the list of Daumier's lithographed plates compiled in 1904 numbers no fewer than 3,958 — he also painted. Except for the searching truthfulness of his vision and the powerful directness of his brushwork, it would be difficult to recognize the creator of Robert Macaire, of Les Bas bleus, Les Bohémiens de Paris, and the Masques, in the paintings of Christ and His Apostles (Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam), or in his Good Samaritan, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, Christ Mocked, or even in the sketches in the Ionides Collection at South Kensington--what connects them is the brilliant draftsmanship, as well as Daumier's interest in the human condition. As the paintings were never intended for public consumption, Daumier felt free to work in a vein that was personal rather than political. In their more munificent spirit the paintings are close to those of his friends Corot and Millet, though altogether more vigorous in handling.

As a painter, Daumier, one of the pioneers of naturalism, did not meet with success until a year before his death in 1878, when M. Durand-Ruel collected his works for exhibition at his galleries and demonstrated the range of the talent of the man who has been called the "Michelangelo of caricature". At the time of the exhibition, Daumier was blind and living in a cottage at Valmondois, which Corot placed at his disposal. It was there that he died.

An exhibition of his works was held at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1900.

Today, Daumier's works are found in many of the world's leading art museums, including the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Rijksmuseum. He is celebrated for a range of works, including a large number of paintings (29) and drawings (49) depicting the life of Don Quijote, a theme that fascinated him for the last part of his life.

Baudelaire noted of him: l'un des hommes les plus importants, je ne dirai pas seulement de la caricature, mais encore de l'art moderne. (One of the most important men, I will not say only of caricature, but further of modern art.)

Gallery

Click on an image to view it enlarged.

-

Les Comediens de Société.

Lithograph published in Le Charivari, 1858. -

Les Joueurs d'échecs (The chess players), 1863.

-

Les Trains de Plaisir (The trains of pleasure).

Lithograph published in Le Charivari, 1864. -

Une discussion littéraire à la deuxième Galerie (A literary discussion at the second gallery).

Lithograph published in Le Charivari, 1864. -

Le Wagon de troisième classe (The third-class wagon), 1864.

External links

Example caricatures of various subjects:

- Animals

- Sports

- Music

- Spring

- Carnival, masks, costumes

- Hunting

- Celebrating

- Theater

- Wine

- School

- Summer

- Lawyers

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)