Tibet

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. |

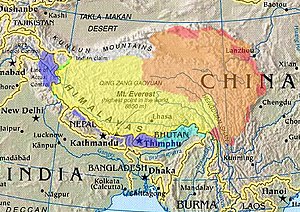

| Claimed by Tibetan exile groups. | |||||||||

| Tibetan areas designated by PRC. | |||||||||

| Tibet Autonomous Region (actual control). | |||||||||

| Claimed by India as part of Aksai Chin. | |||||||||

| Claimed (not controlled) by the PRC as part of TAR. | |||||||||

| Other historically culturally-Tibetan areas. | |||||||||

Tibet (older spelling Thibet; Tibetan: བོད་, Wylie: Bod; pronounced [pʰø̀] in the Lhasa dialect; Chinese: 西藏; pinyin: Xīzàng or simplified Chinese: 藏区; traditional Chinese: 藏區; pinyin: Zàngqū [the two names are used with different connotations; see Name section below]) is a region in Central Asia and the home of the Tibetan people. With an average elevation of 4,900 m (16,000 ft), it is often called the "Roof of the World".

Definitions

When the Government of Tibet in Exile and the Tibetan refugee community worldwide refer to Tibet, they mean a large area that formed the cultural entity of Tibet for many centuries, consisting of the traditional provinces of Amdo, Kham (Khams), and Ü-Tsang (Dbus-gtsang), but excluding areas outside the People's Republic of China (PRC) like Arunachal Pradesh (or South Tibet), Sikkim, Bhutan, and Ladakh that have also formed part of the Tibetan cultural sphere.

When the People's Republic of China refers to Tibet, it means the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR): a province-level entity which, according to the territorial claims of the PRC, includes Arunachal Pradesh (presently under the administration of India). Sikkim, Bhutan, and Ladakh may also be considered to be parts of cultural Greater Tibet in addition to Amdo, Kham, and Ü-Tsang. The TAR covers the Dalai Lama's former domain consisting of Ü-Tsang and western Kham, while Amdo and eastern Kham are now found within the provinces of Qinghai, Gansu, Yunnan, and Sichuan.

The difference in definition is a major sticking point in the dispute. The distribution of Amdo and eastern Kham into surrounding provinces was initiated by the Yongzheng Emperor during the eighteenth century and has been continuously maintained by successive Chinese governments. Tibetan exiles, in turn, consider the maintenance of this arrangement since the eighteenth century as part of a divide-and-rule policy.

A sovereign nation?

Tibet was once an independent kingdom. The government of the People's Republic of China and the Government of Tibet in Exile, however, disagree over when Tibet became a part of China, and whether this incorporation into China is legitimate.

The view of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile

In 1959, the 14th Dalai Lama fled Tibet and established a government in exile at Dharamsala in northern India. This group claims sovereignty over various ethnically or historically Tibetan areas now governed by China. Aside from the Tibet Autonomous Region, an area that was administered directly by the Dalai Lama's government until 1951, the group also claims Amdo (Qinghai) and eastern Kham (western Sichuan)[1]. About 45 percent of China's ethnic Tibetans live in TAR, according to the 2000 census. Prior to 1949, much of Amdo and eastern Kham were governed by local Tibetan rulers.

"During the time of Genghis Khan and Altan Khan of the Mongols, the Ming dynasty of the Chinese, and the Qing Dynasty of the Manchus, Tibet and China cooperated on the basis of benefactor and priest relationship," according to a proclamation issued by 13th Dalai Lama in 1913. The relationship did not imply, "subordination of one to the other." He condemned the Chinese authorities for attempting to colonize Tibetan territory in 1910-12. "We are a small, religious, and independent nation," the proclamation states.[2]

The view of the current Dalai Lama is as follows:

During the Vth Dalai Lama's time [1617-1682], I think it was quite evident the we were a separate sovereign nation with no problems. The VIth Dalai Lama [1683-1706] was spiritually pre-eminent, but politically, he was weak and disinterested. He could not follow the Vth Dalai Lama's path. This was a great failure. So, then the Chinese influence increased. During this time, the Tibetans showed quite a deal of respect to the Chinese. But even during these times, the Tibetans never regarded Tibet as a part of China. All the documents were very clear that China, Mongolia and Tibet were all separate countries. Because the Chinese emperor was powerful and influential, the small nations accepted the Chinese power or influence. You cannot use the previous invasion as evidence that Tibet belongs to China. In the Tibetan mind, regardless of who was in power, whether it was the Manchus, the Mongols or the Chinese, the east of Tibet was simply referred to as China. In the Tibetan mind, India and China were treated the same; two separate countries.[3]

The International Commission of Jurists [4], A non-governmental human rights organization, concluded that Tibet in 1913-50 demonstrated the conditions of statehood as generally accepted under international law. In the opinion of the commission, the government of Tibet conducted its own domestic and foreign affairs free from any outside authority and countries with whom Tibet had foreign relations are shown by official documents to have treated Tibet in practice as an independent State.[5] [6]

The United Nations General Assembly passed resolutions urging respect for the rights of Tibetans in 1959 [7], 1961 [8] and 1965 [9]. The 1961 resolution, in the opinion of the Tibetan Government-in-exile, asserts that "principle of self-determination of peoples and nations" applies to the Tibetan people.

The Tibetan Government in Exile views current PRC rule in Tibet as colonial and illegitimate, motivated solely by the natural resources and strategic value of Tibet, and in gross violation of both Tibet's historical status as an independent country and the right of Tibetan people to self-determination. It also points to PRC's autocratic policies, divide-and-rule policies, and what it contends are assimilationist policies, and regard those as an example of ongoing Chinese imperialism aimed at destroying Tibet's distinct ethnic makeup, culture, and identity, thereby cementing it as an indivisible part of China. That said, the Dalai Lama has recently stated that he wishes only for Tibetan autonomy, and not separation from China, under certain democratic conditions, like freedom of speech and expression and genuine self-rule [10]. Another view supported by a number of international groups including the Free Tibet Campaign is that Tibet should be granted total independence from China.

The Chinese view

Imperial China held that the emperor was the rightful ruler of the world and that other rulers were either vassals or rebels. It was therefore possible for the emperor to issue decrees he considered valid in Tibet without the issue of Tibet's territorial sovereignty arising. In the late 19th century, China adopted the Western model of nation-state diplomacy and a series of treaties regarding Tibet's boundaries and status were concluded.

- Historical status - On the status of Tibet, nevertheless, the view of the government of China, whether Han or non-Han, whether imperial, republican, or communist, has been consistent.[11] The position of the PRC, which has ruled mainland China since 1949, as well as the official position of the Republic of China, which ruled mainland China before 1949 and currently controls Taiwan [12], is that Tibet has been an indivisible part of China de jure since the Yuan Dynasty seven hundred years ago [13], comparable to other states such as the Kingdom of Dali and the Tangut Empire that were also incorporated into the Middle Kingdom at the time and have remained in China ever since. The PRC contends that according to the Succession of states theory in international law all subsequent Chinese governments (Ming Dynasty, Qing Dynasty, ROC and PRC) have succeeded the Yuan Dynasty in exercising de jure sovereignty and de facto power over Tibet.

- Unique ethnicity - According to the current government, successive Chinese governments have recognized Tibet as having its own unique culture (despite heavy influence by that of China Proper [14]) and language; however, they believe that this situation, does not necessarily militate in favor of independence, because China itself has over fifty unique ethnic groups and is one of many multi-national states in the world. The PRC contends that the "Patron-Priest" relationship (Tibetan: chöyön, Wylie: mchod-yon) held between the Chinese central authorities and the Tibetan locality was not equal at all but rather one of superior to inferior. Furthermore, since at least the 18th century, when the Qing Government setting up its local government structure and promulgated laws for the governing, Beijing has, in the words of a foreign missionary who witnessed, had "absolute dominion over Tibet" [15]. The Chinese Resident Ministers in Tibet, namely Ambans, were bestowed power which, according to the Imperial Ordinance promulgated in 1793, was on a par with the local spiritual leaders of Dalai Lamas and Panchen Lamas[16]. The Ambans, according to the Ordinance, were in absolute charge of financial, diplomatic, and trade matters.

- De facto independence - The ROC government had indeed no effective control over Tibet in the year 1912 to 1951; however, in the opinion of the Chinese government, this condition does not represent Tibet's complete independence as many other parts of China also enjoyed de facto independence when the Chinese nation was torn by the local warlords and, later, the civil war [17]. China insists that during this period the ROC government continued to maintain sovereignty over Tibet [18][19], and on other occasions Tibet even indicated its willingness to accept subordinate status as part of China provided that Tibetan internal systems were left untouched and provided China relinquished control over a number of important ethnic Tibetan groups in Kham and Amdo [20][21]. Throughout the Kuomintang years, no country gave Tibet diplomatic recognition [22]. Delegates from Tibetan areas attended the Drafting Committee for a new constitution of the Republic of China in 1925, the National Assembly of the Republic of China in 1931; the fourth National Congress of the Kuomintang in 1931; and a National Assembly for drafting a new Chinese constitution in 1946. A "Trade Mission" sent by the Tibetan government attended another National Assembly for drafting a new Chinese constitution in 1948.[19][23]

- Foreign interventions - Finally, the PRC considers all proindependence movements aimed at ending Chinese sovereignty in Tibet, including British attempts to establish control in the late 19th century and early 20th century [24], the CIA's backing of Tibetan insurgents during the 1950s and 1960s, and the Government of Tibet in Exile today, as one long campaign abetted by malicious Western imperialism aimed at destroying Chinese integrity and sovereignty, thereby weakening China's position in the world [25].

- Human Rights - PRC argues that the Tibetan authority under successive Dalai Lamas was itself a human rights violator while the old society was basically a serfdom and, according to foreigners who witnessed it, slaves even existed [26]. The three UN resolutions of 1959, 1961, and 1965 condemned human rights violation in Tibet; however, these resolutions were passed at a time when the PRC was not permitted to become a member and of course was not allowed to present its version of events in the region. A prominent Tibetologist further notes that:

These resolutions served no practical purpose. None even mentioned China by name, nor did they question the legitimacy of Chinese rule in Tibet (the 1961 resolution did regret, in passing, the depravation of the right to self-determination)—worded, as they were, solely to express regrets over the alleged abuse of "human rights" in Tibet. The UN's denunciation of those who did not act "reasonably" and "fairly" flew in the face of its own actions of denying the PRC membership during this period. It is hardly surprising that the Chinese government regarded these resolutions with little more than contempt. [27]

- Self-determination - While the earliest ROC constitutional documents already claim Tibet as part of China, Chinese political leaders also acknowledged the principle of self-determination. For example, at a party conference in 1924, Kuomintang leader Sun Yat-sen issued a statement calling for the right of self-determination of all Chinese ethnic groups: "The Kuomintang can state with solemnity that it recognizes the right of self-determination of all national minorities in China and it will organize a free and united Chinese republic."[28] In 1931, the CCP issued a constitution for the short-lived Jiangxi Soviet which states that Tibetans and other ethnic minorities, "may either join the Union of Chinese Soviets or secede from it."[29][30] The possibility of complete secession was denied by Communist leader Mao Zedong in 1938: "They must have the right to self-determination and at the same time they should continue to unite with the Chinese people to form one nation". [30] This policy was codified in PRC's first constitution which, in Article 3, reaffirmed China as a "single multi-national state," while the "national autonomous areas are inalienable parts".[30] The Chinese government insists that the United Nations documents, which codifies the principle of self-determination, provides that the principle shall not be abused in disrupting territorial integrity: "Any attempt aimed at the partial or total disruption of the national unity and the territorial integrity of a country is incompatible with the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations...."[31]

- Legitimacy - The PRC also points to the autocratic, oppressive and theocratic policies of the government of Tibet before 1959, its toleration of existence of serfdom and slaves[26], its renunciation of Arunachal Pradesh which China regards as a part of Tibet occupied by India, and its association with India and other foreign countries, and as such claims the Government of Tibet in Exile has no legitimacy to govern Tibet and no credibility or justification in criticizing PRC's policies.

Third-Party views

As of 2006, no country publicly accepts Tibet as an independent state [32], in spite of several instances of government officials appealing to their superiors to do so [33]. Treaties signed by Britain and Russia in the early years of the twentieth century [34] and others signed by Nepal and India in the 1950s [35], recognized Tibet's political subordination to China. The Americans presented their view on 15 May 1943:

For its part, the Government of the United States has borne in mind the fact that...the Chinese constitution lists Tibet among areas constituting the territory of the Republic of China. This Government has at no time raised a question regarding either of these claims. [36]

Not a single sovereign state, including India, has extended recognition to the Tibetan Government-in-exile in the more than two decades of its existence, despite obvious precedents for such an action. This lack of legal recognition of independence has forced even some strong supporters of the refugees to admit that:

...even today international legal experts sympathetic to the Dalai Lama's cause find it difficult to argue that Tibet ever technically established its independence of the Chinese Empire, imperial, or republican. [37]

In spite of these circumstances, there recently has been a concerted effort by lawyers, particularly in the United States, to build a legal case for Tibetan independence, and there is a growing literature on this topic. The Montevideo Convention establishes four criteria for statehood in international law: (a) a permanent population, (b) a defined territory, (c) a government, and (d) capability of entering into relations with other states. Tibet fulfills those requirements. However, so does the Canadian province of Quebec, every U.S. state, Chechnya, Northern Ireland among others.

Name

In Tibetan

Tibetans call their homeland Bod (བོད་), pronounced pö in Lhasa dialect. It is first attested in the geography of Ptolemy as βαται (batai) and in Chinese texts as fa (Beckwith, C. U. of Indiana Diss. 1977). They refer to a fatherland (pha yul), rather than a motherland as does Chinese.

In Chinese

The Chinese name for Tibet, 西藏 (Xīzàng), is a phonetic transliteration derived from Tsang (western Ü-Tsang) The name originated during the Qing Dynasty of China. It can be broken down into Xi 西 (literally "West"), and Zang 藏 (literally "store house"). The term can be interpreted as either "Western Treasure House", or "Storage place of/in the West".

The government of the People's Republic of China equates Tibet with the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR). As such, the name "Xizang" is equated with the TAR. In order to refer non-TAR Tibetan areas, or to all of cultural Tibet, the term 藏区 Zàngqū (literally, "ethnic Tibetan areas") is used. However, Chinese-language versions of pro-Tibetan independence websites, such as the Free Tibet Campaign, the Voice of Tibet, and Tibet Net use 西藏 ("Xizang"), not 藏区 ("Zangqu"), to mean historic Tibet.

Some English-speakers reserve "Xizang", the Chinese word transliterated into English, for the TAR, to keep the concept distinct from that of historic Tibet. Some pro-independence advocates duplicate the situation into the Chinese language, and use 土伯特 or 图伯特, which are both phonetic transcriptions of the word "Tibet", to refer to historic Tibet, though this usage is rare.

The character 藏 (zàng) has been used in transcriptions referring to Tsang as early as the Yuan Dynasty, if not earlier, though the modern term "Xizang" was devised in the 18th century. The Chinese character 藏 (Zàng) has also been generalized to refer to all of Tibet, including other concepts related to Tibet such as the Tibetan language (藏文, Zàngwén) and the Tibetan people (藏族, Zàngzú). The two characters of Xīzàng can literally mean "western storehouse", which some Tibetans find offensive and indicative of what they see as Chinese colonial attitudes towards Tibet. However, the offending character, "zàng", can also mean "treasure" or "Buddhist scripture". In addition, Chinese transliterations of non-Chinese names do not necessarily take into account the literal meanings of words; usually a positive or neutral connotation combined with phonetic similarity is enough for the transliteration to come into use. See Transliteration into Chinese characters for other examples.

In English

The English word Tibet, like the word for Tibet in most European languages, is derived from the Arabic word Tubbat. There are several theories as to the origin of this word. According to one, it is derived via Persian from the Turkic word Töbän (pl. Töbäd), meaning "the heights".[38] According to another theory, Tubbat is derived from the Chinese 吐蕃 (Pinyin tǔfān, but in ancient times pronounced tǔbō), used to refer to the Tibetan Empire of the 7th–11th centuries).[39] The Sanskrit word for Tibet is Bhoṭa.

Cities

Lhasa is Tibet's traditional capital and the capital of Tibet Autonomous Region. Other cities in Historic Tibet include, in the TAR, Shigatse (Gzhis-ka-rtse), Gyantse (Rgyal-rtse), Chamdo (Chab-mdo), Nagchu, Nyingchi (Nying-khri), Nedong (Sne-gdong), Barkam ('Bar-khams), Sakya (Sa-skya), Gartse (Dkar-mdzes), Pelbar (Dpal-'bar), and Tingri (Ding-ri); in Sichuan, Dartsendo (Dar-btsen-mdo); in Qinghai, Kyegundo (Skye-rgu-mdo) or Yushu (Yul-shul), Machen (Rma-chen), Lhatse (Lhar-tse), and Golmud (Na-gor-mo).

History

Early days

The Tibetan language is generally considered to be a Tibeto-Burman language and distantly related to Chinese.

In general, the history of Tibet begins with King Srong-tsan-gam-po Songtsen Gampo (604–650 CE), although there were 27 kings before him. [40] King Songtsen Gampo is generally considered to have introduced Buddhism to Tibet at this time. Christianity is known to have been present in Tibet prior to 782.

King Songtsen Gampo sought to marry Princess Wen-Cheng, a member of the extended royal family of the Tang Dynasty.

Conflict between Tibet and the Tang began as Tu-Yu Huen was against the marriage. Tibet sent an army to drive it from the valleys around the source of Huang He. After several indecisive battles, and gaining recognition as a local power, the Tang became receptive.

Tang history records the marriage to 641 AD.

The next Tang emperor sent General Hsueh Zen-Kuei with an army to recover Tu-Yu Huen for the southern part of Qinghai (Amdo in Tibetan). A Tibetan army defeated him on the high plateau of Qinghai. Subsequently, Tibet conquered all small tribes in Qinghai and southern Xinjiang.

During this period, Tibet had a population of 10 million with 3 million Tibetans and an army of comparable strength facing the two Tang armies of Southern Xinjiang (24,000 soldiers) and of the Silk Road (75,000 soldiers). Disputes involved trade controls. Tibet wanted the four Tang garrisons at the Southern Xinjiang (which guarded the silk-road from central Tang through Xinjiang and Central Asia). After the Tang's withdrawal of the Silk-road army and its garrison troops of Northern and Southern Xinjiang during the An Lu-san rebellion, Tubo (Tibetan) military power conquered all of that territory up to the border of the Hue-He (Mongols), capturing the Silk-road.

Tibet attacked Sichuan and fought many inconclusive battles with the Tang. The Tibetan army ransacked Changan, now Xi'an, the capital of Tang Empire, and crowned an emperor who lasted for a few days (763).

Tibet had also conquered the ethnic tribes scattered in the present areas of Lijiang and Dali, Yunnan, and had established a military administration in northwest Yunnan. Yunnan was a tributary of Tibet. Tibet also bordered with India, and Persia. This was the largest area which was ever controlled by Tibet.

The military route used by the Tibetans to reach Yunnan was closely related to the contemporary tea and horse route. “Tea and Horse Caravan Road” of Southwest China is less well known than the famous Silk Road.

According to the Tibetan book “Historic Collection of the Han and Tibet” (Han Zang shi ji) “In the reign of the Tibetan King Chidusongzan [Khri ‘Dus sron] (676-704), the Tibetan aristocracy started to drink tea and use the tea-bowl, and tea was classified into different categories.”[41]

After the downfall of the Tibetan Dynasty, the Tang recovered Silk-road (848). According to one study, more than 20,000 warhorses per year were exchanged for tea during the Northern Song (960-1127) dynasty.

The distinctive form of Tibetan society, in which land was divided into three different types of holding—estates of noble families, freeheld lands and estates held by monasteries of particular Tibetan Buddhists sects—arose after the weakening of the Tibetan kings in the 10th century. This form of society was to continue into the 1950s, at which time more than 700,000 of the country's population of 1.25 million were serfs.

Mongols & Manchus

In 1240, the Mongols marched into central Tibet and attacked several monastaries. Köden, younger brother of Mongol ruler Güyük Khan, participated in a ceremony recognizing the Sa-skya lama as temporal ruler Tibet in 1247. The Mongol khans had ruled northern China since 1215. They declared themselves Chinese emperors in 1271 as the Yuan dynasty. Kublai Khan was a patron of Tibetan Buddhism and appointed the Sa-skya Lama his "Imperial preceptor," or chief religious official. Tibetans viewed this relationship as an example of yon-mchod, or priest-patron relationship. In practice, the Sa-skya lama was subordinate to the Mongol khan. The collapse of the Yuan dynasty in 1368 led to the overthrow of the Sa-skya in Tibet. Tibet was then ruled by a succession of three secular dynasties. In the 16th century, Altan Khan of Tumet Mongolian tribe supported the Dalai Lama's religious lineage to be the dominant religion among Mongols and Tibetans.

Beginning in the early 18th century, China's dynastic central government sent resident commissioner (amban) to Lhasa. Tibetan factions rebelled in 1750 and killed the ambans. Then, a Qing army entered and defeated the rebels and installed an administration headed by the Dalai Lama. The number of soldiers in Tibet was kept at about 2000. The defensive duties were partly helped out by a local force which was reorganized by the resident commissioner, and the Tibetan government continued to manage day-to-day affairs as before.

In 1841 Tibet was invaded by the army of General Zorawar Singh from the Indian Kingdom of Jammu & Kashmir. After his death in the Battle of To'Yo the Sino-Tibetan armies invaded Jammu but were defeated at the Battle of Chushul——a treaty signed at that place marked out the boundaries of India and Tibet.

British influence

Main article: British expedition to Tibet

In 1904 a British diplomatic mission, accompanied by a large military escort, forced its way through to Lhasa. The head of the diplomatic mission was Colonel Francis Younghusband. The principal motivation for the British mission was a fear, which proved to be unfounded, that Russia was extending its footprint into Tibet and possibly even giving military aid to the Tibetan government. When the mission reached Lhasa, the Dalai Lama had already fled to Urga in Mongolia, but a treaty was signed by lay and ecclesiastical officials of the Tibetan government, and by representatives of the three monasteries of Sera, Drepung, and Ganden.[42]. The treaty made provisions for the frontier between Sikkim and Tibet to be respected, for freer trade between British and Tibetan subjects, and for an indemnity to be paid from the Tibetan Government to the British Government for its expenses in dispatching armed troops to Lhasa. It also made provision for a British trade agent to reside at the trade mart at Gyantse. The provisions of this 1904 treaty were confirmed in a 1906 treaty signed between Britain and China, in which the British also agreed "not to annex Tibetan territory or to interfere in the administration of Tibet."[43]. The position of British Trade Agent at Gyantse was occupied from 1904 up until 1944. It was not until 1937, with the creation of the position of "Head of British Mission Lhasa", that a British officer had a permanent posting in Lhasa itself.[44]

A Nepalese agency had also been established in Lhasa after the invasion of Tibet by the Gurkha government of Nepal in 1855[45].

In the Anglo-Chinese Convention of 1906 which confirmed the Anglo-Tibetan Treaty of 1904, Britain agreed "not to annex Tibetan territory or to interfere in the administration of Tibet" while China engaged "not to permit any other foreign State to interfere with the territory or internal administration of Tibet"[46]. In the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, Britain also recognized the "suzerainty of China over Thibet" and, in conformity with such admitted principle, engaged "not to enter into negotiations with Thibet except through the intermediary of the Chinese Government."[47] Suzerainty is a situation in which a region or people is a tributary to a more powerful entity which allows the tributary some limited domestic autonomy but controls its foreign affairs. The Qing central government established direct rule over Tibet for the first time in 1910. The thirteenth Dalai Lama fled to British India in February 1910. In the same month, the Chinese Qing government issued a proclamation deposing the Dalai Lama and instigating the search for a new incarnation[48]. While in India the Dalai Lama became a close friend of the British Political Officer Charles Bell. The official position of the British Government was that they would not intervene between China and Tibet, and it would only recognize the de facto government of China within Tibet at this time[49]. In Bell's history of Tibet, he would write of this time that "the Tibetans were abandoned to Chinese aggression, an aggression for which the British Military Expedition to Lhasa and subsequent retreat [and consequent power vacuum within Tibet] were primarily responsible"[50].

Relations with the Chinese Republic

In February of 1912 the Qing emperor abdicated and the new Republic of China was formed [51]. In April of 1912 the Chinese garrison of troops in Lhasa surrendered to the Tibetan authorities. The new Chinese Republican government wished to make the commander of the Chinese troops in Lhasa their new Tibetan representative, but the Tibetans were in favour of having all of the Chinese troops return to China Proper. The Dalai Lama returned to Tibet from India in July 1912. By the end of 1912, the Chinese troops in Tibet had returned, via India, to China Proper[51]. In 1913, Tibet and Mongolia signed a treaty proclaiming mutual recognition and their independence from China. In 1914, a treaty was negotiated in India by representatives of China, Tibet and Britain: the Simla Convention. During the convention, the British tried to divide Tibet into Inner and Outer Tibet. When negotiations broke down over the specific boundary between Inner and Outer, the British demanded instead to advance their line of control, enabling them to annex 90,000 square kilometers of traditional Tibetan territory in southern Tibet, which corresponds to most of the modern Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh, while recognizing Chinese suzerainty, but not sovereignty, over Tibet. Tibetan representatives secretly signed under British pressure; however, the representative of Chinese central government declared that the secretive annexation of territory was not acceptable. The boundary established in the convention, the McMahon Line, was considered by the British and later the independent Indian government to be the boundary; however, the Chinese view since then has been that since China, which was sovereign over Tibet, did not sign the treaty, the treaty was meaningless, and the annexation and control of southern Tibet / Arunachal Pradesh by India is illegal. This paved the way to the Sino-Indian War of 1962 and the boundary dispute between China and India today.

The subsequent outbreak of World War I and civil war in China caused the Western powers and the infighting factions of China proper to lose interest in Tibet, and the 13th Dalai Lama ruled undisturbed. At that time, the government of Tibet controlled all of Ü-Tsang (Dbus-gtsang) and western Kham (Khams), roughly coincident with the borders of Tibet Autonomous Region today. Eastern Kham, separated by the Yangtze River was under the control of Chinese warlord Liu Wenhui. The situation in Amdo (Qinghai) was more complicated, with the Xining area controlled by ethnic Hui warlord Ma Bufang, who constantly strove to exert control over the rest of Amdo (Qinghai).

Relations with the People's Republic of China

Neither the Republic of China nor the People's Republic of China has ever renounced China's claim to sovereignty over Tibet [52]. In 1950, the People's Liberation Army entered the Tibetan area of Chamdo, crushing nominal resistance from the ill-equipped Tibetan army. In 1951, the Seventeen Point Agreement was reached, under PLA's military pressure, by representatives of the Dalai Lama and Beijing affirming Chinese sovereignty over Tibet with a joint administration under representatives of the central government and the Tibetan government. Most of the population of Tibet at that time were peasants, often bound to land owned by monasteries and aristocrats. Any attempt at land redistribution or the redistribution of wealth would have proved unpopular with the established landowners. This agreement was initially put into effect in Tibet proper. However, Eastern Kham and Amdo were outside the administration of the government of Tibet, and were thus treated like any other Chinese province with land redistribution implemented in full. As a result, a rebellion broke out in Amdo and eastern Kham in June of 1956. The insurrection, supported by the American CIA, eventually spread to Lhasa. It was crushed by 1959. Tibetan exiles claim that during this campaign, tens of thousands of Tibetans were killed. The 14th Dalai Lama and other government principals fled to exile in India, but isolated resistance continued in Tibet until 1969 when CIA support was withdrawn.

Although the Panchen Lama remained a virtual prisoner, the Chinese set him as a figurehead in Lhasa, claiming that he headed the legitimate Government of Tibet in the absence of the Dalai Lama, the traditional head of the Tibetan government. In 1965, the area that had been under the control of the Dalai Lama's government from the 1910s to 1959 (U-Tsang and western Kham) was set up as an Autonomous Region. The monastic estates were broken up and secular education introduced. During the Cultural Revolution, the Red Guards inflicted a campaign of organized vandalism against cultural sites in the entire PRC, including Tibet's Buddhist heritage. Many young Tibetans joined in the campaign of destruction, voluntarily due to the ideological fervour that was sweeping the entire PRC [53][54] and involuntarily due to the fear of being denounced as "enemies of the people" [55]. Of the several thousand monasteries in Tibet, over 6000 were destroyed [56], only a handful remained without major damage, and thousands of Buddhist monks and nuns were killed or imprisoned.

Since 1979, there have been major economic changes, like the rest of the PRC, but the political system remains undemocratic and repressive. Some PRC policies in Tibet have been described as moderate, while others are judged to be more oppressive. Most religious freedoms have been officially restored, provided the lamas do not challenge PRC rule. Foreigners can visit most parts of Tibet, and it is claimed that the less savoury aspects of PRC rule are kept hidden from visitors.

In 1989, the Panchen Lama died, and the Dalai Lama and the PRC recognised different reincarnations. While officially an atheist state, the People's Republic of China has affirmed its right to confirming high-level reincarnations, a tulku in the Tibetan tradition of Vajrayana Buddhism, citing a precedent set by the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing Dynasty (The PRC view is that Qianlong instituted a system of selecting the Panchen Lama, the Dalai Lama and other high lamas by means of a lottery which utilised a golden urn with names wrapped in barley balls;[57] the view of Tibetan exiles is that the system was a suggestion made by Qianlong and was not a prerequisite for choosing the Panchen Lama). The Dalai Lama named Gedhun Choekyi Nyima as the 11th Panchen Lama but without confirmation by the vase lot, while the PRC named another child, Gyancain Norbu by the vase lot. Gyancain Norbu was raised in Beijing and has appeared occasionally on state media. Gedhun Choekyi Nyima and his family have gone missing, into imprisonment according to Tibetan exiles, and under a hidden identity for protection and privacy according to the PRC.[58]

The PRC continues to portray its rule over Tibet as an unalloyed improvement, and foreign governments continue to make occasional protests about aspects of PRC rule in Tibet. All governments, however, recognise PRC sovereignty over Tibet, and none has recognised the Dalai Lama's government in exile in India.

Evaluation of PRC rule

The neutrality of this section is disputed. |

Evaluation by the Tibetan exile community

Tibetan exiles generally say that the number that have died in the Great Leap Forward, of violence, or other unnatural causes since 1950 is approximately 1.2 million, which the Chinese Communist Party denies. According to Patrick French, the estimate is not reliable because the Tibetans were not able to process the data well enough to produce a credible total. There were, however, many casualties, perhaps as many as 400,000. This figure is extrapolated from a calculation Warren W. Smith made from census reports of Tibet which show 200,000 "missing" from Tibet.[59][60] Even The Black Book of Communism expresses doubt at the 1.2 million figure, but does note that according to Chinese census the total population of ethnic Tibetans in the PRC was 2.8 million in 1953, but only 2.5 million in 1964. It puts forward a figure of 800,000 deaths and alleges that as many as 10% of Tibetans were interned, with few survivors.[61] Chinese demographers have estimated that 90,000 of the 300,000 "missing" Tibetans fled the region.[62]

The government of Tibet in Exile also says that, fundamentally, the issue is that of the right to self-determination of the Tibetan people. While refusing to agree to China's demands that he renounce the idea that Tibet was once an independent country, the Dalai Lama has stated his willingness to negotiate with China for "genuine autonomy" (over the objection of those Tibetans who push for full independence). The Dalai Lama sees the millions of Han immigrants, attracted to the TAR by economic incentives and preferential socioeconomic policies, as presenting an urgent threat to the Tibetan nation by diluting the Tibetans both culturally and through intermarriage. Exile groups say that despite recent attempts to restore the appearance of original Tibetan culture to attract tourism, the traditional Tibetan way of life is now irrevocably changed. It is also reported that when Hu Yaobang, the general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, visited Lhasa in 1980 he was unhappy when he found out the region was behind neighbouring provinces. Policies were changed, and since then the central government's policy in Tibet has granted most religious freedoms. But monks and nuns are still sometimes imprisoned [63], and many Tibetans (mostly monks and nuns) continue to flee Tibet yearly. At the same time, many Tibetans view projects that the PRC claims to benefit Tibet, such as the China Western Development economic plan or the Qinghai-Tibet Railway, as politically-motivated actions to consolidate central control over Tibet by facilitating militarization and Han migration while benefiting few Tibetans; they also view the money funneled into cultural restoration projects as being aimed at attracting foreign tourists. They note that Tibet is still behind the rest of the PRC: for example, the first big hospital in Tibet was not built until 1985; that several of Lhasa's main roads weren't paved until 1987; and that the first students at Tibet University didn't graduate until 1988. [citation needed] They also say that there is still preferential treatment awarded to Han in the labor market as opposed to Tibetans.

Evaluation by the People's Republic of China

The government of the PRC says that the population of Tibet in 1737 was about 8 million, and that due to the backward rule of the local theocracy, there was rapid decrease in the next two hundred years and the population in 1959 was only about 1.19 million. Today, the population of Greater Tibet is 7.3 million, of which, according to the 2000 census, 5 million are ethnic Tibetans. The government of the PRC views this population growth as the result of the abolishment of the theocracy and introduction of a modern, higher standard of living. Based on the census numbers, the PRC also rejects claims that the Tibetans are being swamped by Han Chinese; instead the PRC says that the border for Greater Tibet drawn by the government of Tibet in Exile is so large that it incorporates regions such as Xining that are not traditionally Tibetan in the first place, hence exaggerating the number of non-Tibetans.

The government of the PRC also rejects claims that the lives of Tibetans have deteriorated, pointing to rights enjoyed by the Tibetan language in education and in courts and says that the lives of Tibetans have been improved immensely compared to the Dalai Lama's rule before 1950.[1] Benefits that are commonly quoted include: the GDP of Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) today is 30 times that before 1950; TAR has 22,500 km of highways, as opposed to 0 in 1950; all secular education in TAR was created after the revolution; TAR now has 25 scientific research institutes as opposed to 0 in 1950; infant mortality has dropped from 43% in 1950 to 0.661% in 2000; life expectancy has risen from 35.5 years in 1950 to 67 in 2000; the collection and publishing of the traditional Epic of King Gesar, which is the longest epic poem in the world and had only been handed down orally before; allocation of 300 million Renminbi since the 1980s to the maintenance and protection of Tibetan monasteries [2]. The Cultural Revolution and the cultural damage it wrought upon the entire PRC is generally condemned as a nationwide catastrophe, whose main instigators (in the PRC's view, the Gang of Four) have been brought to justice and whose reoccurrence is unthinkable in an increasingly modernized China. The China Western Development plan is viewed by the PRC as a massive, benevolent, and patriotic undertaking by the eastern coast to help the western parts of China, including Tibet, catch up in prosperity and living standards.

Geography

Tibet is located on the Tibetan Plateau, the world's highest region. Most of the Himalaya mountain range lies within Tibet. Its most famous peak, Mount Everest, is on Nepal's border with Tibet.

The atmosphere is severely dry nine months of the year. Western passes receive small amounts of fresh snow each year but remain traversable year round. Low temperatures are prevalent throughout these western regions, where bleak desolation is unrelieved by any vegetation beyond the size of low bushes, and where wind sweeps unchecked across vast expanses of arid plain. The Indian monsoon exerts some influence on eastern Tibet. Northern Tibet is subject to high temperatures in summer and intense cold in winter.

Historic Tibet consists of several regions:

- Amdo (A mdo) in the northeast, incorporated by China into the provinces of Qinghai, Gansu and Sichuan.

- Kham (Khams) in the east, divided between Sichuan, northern Yunnan and Qinghai.

- Western Kham, part of the Tibetan Autonomous Region

- U (dBus), in the center, and Tsang (gTsang) in the center-west, part of the Tibetan Autonomous Region

- Ngari (mNga' ris) in the far west, part of the Tibetan Autonomous Region

Tibetan cultural influences extend to the neighboring states of Bhutan, Nepal, adjacent regions of India such as Sikkim and Ladakh, and adjacent provinces of China where Tibetan Buddhism is the predominant religion.

On the border with India, the region popularly known among Chinese as South Tibet is claimed by China and administered by India as the state of Arunachal Pradesh.

Several major rivers have their source in the Tibetan Plateau (mostly in present-day Qinghai Province), including:

Economy

The Tibetan economy is dominated by subsistence agriculture. Due to limited arable land, livestock raising is the primary occupation. In recent years, due to the increased interest in Tibetan Buddhism tourism has become an increasingly important sector, and is actively promoted by the authorities.

The Qinghai-Tibet Railway which links the region to Qinghai in China proper was opened in 2006.[64]China says the line will promote the development of impoverished Tibet.[65]But opponents argue the railway will harm Tibet. For instance, some Tibetans contend that it would only draw more Han Chinese residents, the country's dominant ethnic group, who have been migrating steadily to Tibet over the last decade, bringing with them their popular culture. These Tibetans believe that the large influx of Han Chinese will ultimately extinguish the local culture. [66]Other opponents argue that the railway will damage Tibet's fragile ecology and that most of its economic benefits will go to migrant Han Chinese [67]. As activists call for a boycott of the railway, the Dalai Lama has urged Tibetans to "wait and see" what benefits the new line might bring to them. According to Government-in-exile's spokemen, the Dalai Lama welcomes the building of the railway, "conditioned on the fact that the railroad will bring benefit to the majority of Tibetans." [68]

Demographics

Historically, the population of Tibet consisted of primarily ethnic Tibetans. Other ethnic groups in Tibet include Menba (Monpa), Lhoba, Mongols and Hui. According to tradition the original ancestors of the Tibetan people, as represented by the six red bands in the Tibetan flag, are: the Se, Mu, Dong, Tong, Dru and Ra.

The issue of the proportion of the Han Chinese population in Tibet is a politically sensitive one. The Tibetan Government-in-Exile says that the People's Republic of China has actively swamped Tibet with Han Chinese migrants in order to alter Tibet's demographic makeup, while the People's Republic of China has denied this.

View of the Tibetan exile community

Between the 1960s and 1980s, many prisoners (over 1 million, according to Harry Wu) were sent to laogai camps in Amdo (Qinghai), where they were then employed locally after release. Since the 1980s, increasing economic liberalization and internal mobility has also resulted in the influx of many Han Chinese into Tibet for work or settlement, though the actual number of this floating population remains disputed. The Government of Tibet in Exile gives the number of non-Tibetans in Tibet as 7.5 million (as opposed to 6 million Tibetans), and considers this the result of an active policy of demographically swamping the Tibetan people and further diminishing any chances of Tibetan political independence, and as such, to be in violation of the Geneva Convention of 1946 that prohibits settlement by occupying powers. The Government of Tibet in Exile questions all statistics given by the PRC government, since they do not include members of the People's Liberation Army garrisoned in Tibet, or the large floating population of unregistered migrants. The Qinghai-Tibet Railway (Xining to Lhasa) is also a major concern, as it is believed to further facilitate the influx of migrants.

View of the People's Republic of China

The PRC government does not view itself as an occupying power and has vehemently denied allegations of demographic swamping. The PRC also does not recognize Greater Tibet as claimed by the government of Tibet in Exile, saying that the idea was engineered by foreign imperialists as a plot to divide China amongst themselves, and that those areas outside the TAR were not controlled by the Tibetan government before 1959 in the first place, having been administered instead by other surrounding provinces for centuries. [3] The PRC gives the number of Tibetans in Tibet Autonomous Region as 2.4 million, as opposed to 190,000 non-Tibetans, and the number of Tibetans in all Tibetan autonomous entities combined (slightly smaller than the Greater Tibet claimed by exiled Tibetans) as 5.0 million, as opposed to 2.3 million non-Tibetans. In the TAR itself, much of the Han population is to be found in Lhasa. Population control policies like the one-child policy only apply to Han Chinese, not to minorities such as Tibetans. Jampa Phuntsok, chairman of the TAR, has also said that the central government has no policy of migration into Tibet due to its harsh high-altitude conditions, that the 6% Han in the TAR is a very fluid group mainly doing business or working, and that there is no immigration problem. [4]

| Major ethnic groups in Greater Tibet by region, 2000 census | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Tibetans | Han Chinese | others | ||||

| Tibet Autonomous Region: | 2616329 | 2427168 | 92.8% | 158570 | 6.1% | 30591 | 1.2% |

| - Lhasa PLC | 474499 | 387124 | 81.6% | 80584 | 17.0% | 6791 | 1.4% |

| - Chamdo Prefecture | 586152 | 563831 | 96.2% | 19673 | 3.4% | 2648 | 0.5% |

| - Lhokha Prefecture | 318106 | 305709 | 96.1% | 10968 | 3.4% | 1429 | 0.4% |

| - Shigatse Prefecture | 634962 | 618270 | 97.4% | 12500 | 2.0% | 4192 | 0.7% |

| - Nagchu Prefecture | 366710 | 357673 | 97.5% | 7510 | 2.0% | 1527 | 0.4% |

| - Ngari Prefecture | 77253 | 73111 | 94.6% | 3543 | 4.6% | 599 | 0.8% |

| - Nyingtri Prefecture | 158647 | 121450 | 76.6% | 23792 | 15.0% | 13405 | 8.4% |

| Qinghai Province: | 4822963 | 1086592 | 22.5% | 2606050 | 54.0% | 1130321 | 23.4% |

| - Xining PLC | 1849713 | 96091 | 5.2% | 1375013 | 74.3% | 378609 | 20.5% |

| - Haidong Prefecture | 1391565 | 128025 | 9.2% | 783893 | 56.3% | 479647 | 34.5% |

| - Haibei AP | 258922 | 62520 | 24.1% | 94841 | 36.6% | 101561 | 39.2% |

| - Huangnan AP | 214642 | 142360 | 66.3% | 16194 | 7.5% | 56088 | 26.1% |

| - Hainan AP | 375426 | 235663 | 62.8% | 105337 | 28.1% | 34426 | 9.2% |

| - Golog AP | 137940 | 126395 | 91.6% | 9096 | 6.6% | 2449 | 1.8% |

| - Gyêgu AP | 262661 | 255167 | 97.1% | 5970 | 2.3% | 1524 | 0.6% |

| - Haixi AP | 332094 | 40371 | 12.2% | 215706 | 65.0% | 76017 | 22.9% |

| Tibetan areas in Sichuan province | |||||||

| - Aba AP | 847468 | 455238 | 53.7% | 209270 | 24.7% | 182960 | 21.6% |

| - Garzê AP | 897239 | 703168 | 78.4% | 163648 | 18.2% | 30423 | 3.4% |

| - Muli AC | 124462 | 60679 | 48.8% | 27199 | 21.9% | 36584 | 29.4% |

| Tibetan areas in Yunnan province | |||||||

| - Dêqên AP | 353518 | 117099 | 33.1% | 57928 | 16.4% | 178491 | 50.5% |

| Tibetan areas in Gansu province | |||||||

| - Gannan AP | 640106 | 329278 | 51.4% | 267260 | 41.8% | 43568 | 6.8% |

| - Tianzhu AC | 221347 | 66125 | 29.9% | 139190 | 62.9% | 16032 | 7.2% |

| Total for Greater Tibet: | |||||||

| With Xining and Haidong | 10523432 | 5245347 | 49.8% | 3629115 | 34.5% | 1648970 | 15.7% |

| Without Xining and Haidong | 7282154 | 5021231 | 69.0% | 1470209 | 20.2% | 790714 | 10.9% |

This table includes all Tibetan autonomous entities in the People's Republic of China, plus Xining PLC and Haidong P. The latter two are included to complete the figures for Qinghai province, and also because they are claimed as parts of Greater Tibet by the Government of Tibet in exile.

P = Prefecture; AP = Autonomous prefecture; PLC = Prefecture-level city; AC = Autonomous county

Excludes members of the People's Liberation Army in active service.

Source: Department of Population, Social, Science and Technology Statistics of the National Bureau of Statistics of China (国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司) and Department of Economic Development of the State Ethnic Affairs Commission of China (国家民族事务委员会经济发展司), eds. Tabulation on Nationalities of 2000 Population Census of China (《2000年人口普查中国民族人口资料》). 2 vols. Beijing: Nationalities Publishing House (民族出版社), 2003. (ISBN 7-105-05425-5)

Culture

Tibet is the traditional center of Tibetan Buddhism, a distinctive form of Vajrayana, which is also related to the Shingon Buddhist tradition in Japan. Tibetan Buddhism is practiced not only in Tibet but also in Mongolia, the Buryat Republic, the Tuva Republic, and in the Republic of Kalmykia. Tibet is also home to the original spiritual tradition called Bön (also spelled Bon). Various dialects of the Tibetan language are spoken across the country. Tibetan is written in Tibetan script.

In Tibetan cities, there are also small communities of Muslims, known as Kachee (Kache), who trace their origin to immigrants from three main regions: Kashmir (Kachee Yul in ancient Tibetan), Ladakh and the Central Asian Turkic countries. Islamic influence in Tibet also came from Persia. After the invasion of Tibet in 1959 a group of Tibetan Muslims made a case for Indian nationality based on their historic roots to Kashmir and the Indian government declared all Tibetan Muslims Indian citizens later on that year. [5] There is also a well established Chinese Muslim community (gya kachee), which traces its ancestry back to the Hui ethnic group of China. It is said that Muslim migrants from Kashmir and Ladakh first entered Tibet around the 12th century. Marriages and social interaction gradually led to an increase in the population until a sizable community grew up around Lhasa.

The Potala Palace, former residence of the Dalai Lamas, is a World Heritage Site, as is Norbulingka, former summer residence of the Dalai Lama. The PRC government has planned to invest 179.3 million Renminbi in the renovation and restoration of the Potala Palace and 67.4 million Renminbi in the Norbulingka, starting from 2002.

During the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s, zealous Red Guards destroyed or vandalised most historically significant sites in Tibet, as a part of a broader campaign waged across China to destroy pre-Revolution cultural artifacts.

Notes

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C., The Snow Lion and the Dragon, University of California Press, 1997, p71

- ^ Proclamation Issued by His Holiness the Dalai Lama XIII (1913)

- ^ Gyatso, Tenzin, Dalai Lama XIV. Tibet, China and the World: A Compilation of Interviews, Dharamsala, 1989, p. 31.

- ^ This human rights organization should not be confused with the International Court of Justice, the principal judicial organ of the United Nations. The International Commission of Jurists. The CIA was secretly providing funds to the ICJ, although this was not known to leaders of the group at the time. The ICJ was established by the Investigating Committee of Freedom-Minded Lawyers from the Soviet Zone and the League of Free Jurists. It was formed in honor of Dr. Walter Linse.

- ^ Legal Inquiry Committee, Tibet and Chinese People's Republic, Geneva: International Commission of Jurists, 1960, pp. 5,6

- ^ Walt Van Praag, Michael C. van, The Status of Tibet: History, Rights and Prospects in International Law, (Westview, 1987)

- ^ United Nations General Assembly - Resolution 1353 (XIV), New York, 1959

- ^ United Nations General Assembly - Resolution 1723 (XVI), New York, 1961

- ^ United Nations General Assembly - Resolution 2079 (XX), New York, 1965

- ^ Statement of His Holiness the Dalai Lama on the 47th Anniversary of the Tibetan National Uprising Day, March 10 2006

- ^ Grunfeld, 1996, p255

- ^ For PRC's position, see State Council's whitepaper Tibet - Its Ownership and Human Rights Situation, 1992 and Beijing Review's 100 Question about Tibet, 1989; for ROC's position, see Government Information Office's online publication

- ^ Such view is supported by Grunfeld, A. Tom, Reassessing Tibet Policy, 2000 (also in PDF file)

- ^ Oxford Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Arts, 1991, p454

- ^ Zahiruddin Ahmad, "China and Tibet, 1708-1959. A Resume of Facts", 1960, p7

- ^ Goldstein, 1997, p19 & p134 n15; The Ordinance was jointly drafted by General Fu Kangan, the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama in 1792 and promulgated by the Qing Emperor one year later.

- ^ Grunfeld, 1996, p256

- ^ Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China, issued March, 1912; Constitution of the Republic of China, issued May, 1914; Provisional Constitution in the Political Tutelage Period of the Republic of China, issued June 1931

- ^ a b "Did Tibet Become an Independent Country after the Revolution of 1911?", China Internet Information Center

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn C., A History of Modern Tibet: 1913-1951, 1989, pp 239-241

- ^ Grunfeld, A. Tom, The Making of Modern Tibet, M.E. Sharpe, 1996, p245, regarding Kham and Amdo: "The historical reality is that the Dalai Lamas have not ruled these outer areas since the mid-eighteenth century, and during the Simla Conference of 1913, the thirteenth Dalai Lama was even willing to sign away rights to them"

- ^ For the British and U.S. positions on Tibet, see Goldstein, 1989, p 399, p386, UK Foreign Office Whitepaper: Tibet and the Question of Chinese Suzerainty(10 April 1943), Foreign Office Records: FO371/35755 and aide-mémoire sent by the US Department of States to the British Embassy in Washington, D.C.(dated 15 May 1943), Foreign Office Records: FO371/35756

- ^ Li, T.T., The Historical Status of Tibet, King's Crown Press, Columbia University, 1956

- ^ Jacques Gernet's A History of Chinese Civilization [Cambridge University Press, 1996] saying "From 1751 onwards Chinese control over Tibet became permanent and remained so more or less ever after, in spite of British efforts to seize possession of this Chinese protectorate at the beginning of the twentieth century"

- ^ Origins of So-Called "Tibetan Independence, Information Office of the State Council, 1992

- ^ a b For existence of serfdom and slaves, see Grunfeld, 1996, pp12-17 and Bell, Charles, 1927, pp78-79; for other forms of human rights violation, see Bessac, Frank, "This Was the Perilous Trek to Tragedy", Life, 13 Nov 1950, pp130-136, 198, 141; Ford, Robert W., "Wind Between The Worlds", New York, 1957, p37; MacDonald, David, "The Land of the Lamas", London, 1929, pp196-197

- ^ Grunfeld, 1996, p180

- ^ Quoted from National and Minority Policies, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science: Report of China 277, 1951, pp148-149

- ^ Brandt, C., Schwartz, B. and Fairbank, John K. (ed.), A Documentary History of Chinese Communism, 1960, pp223-224

- ^ a b c "Report on the International Seminar on the Nationality Question"

- ^ United Nations Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples

- ^ Goldstein, 1989. The closest it has ever come to such recognition was the British formula of 1943: suzerainty under China, combined with autonomy and the right to enter into diplomatic relations.

- ^ Goldstein, 1989

- ^ Treaties of 1906, 1907 and 1914

- ^ Since then Tibet has been regarded by Nepal and the Republic of India as a Region of China

- ^ Aide-mémoire sent by the US Department of States to the British Embassy in Washington, D.C.(dated 15 May 1943), Foreign Office Records: FO371/35756, quoted from Goldstein, 1989, p386

- ^ Bradsher, Henry S., "Tibet Struggles to Survive, Foreign Affairs, July 1969

- ^ Behr, W. Oriens 34 (1994): 557–564.

- ^ Partridge, Eric, Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English, New York, 1966, p. 719.

- ^ http://omni.cc.purdue.edu/~wtv/tibet/history.html#iif03

- ^ http://www.silkroadfoundation.org/newsletter/2004vol2num1/tea.htm

- ^ Bell, 1924 p. 284; Allen, 2004, p. 282

- ^ Bell, 1924, p. 288

- ^ McKay, 1997, pp. 230-1.

- ^ Bell, 1924, pp. 46-7, 278-80

- ^ Convention Between Great Britain and China Respecting Tibet (1906)

- ^ Convention Between Great Britain and Russia (1907)

- ^ Smith (1996), p. 175

- ^ Bell (1924), p. 113

- ^ Bell (1924), p. 113

- ^ a b Smith (1996), p. 181

- ^ Grunfeld, 1996, pp255-257

- ^ Wang Lixiong, 'Reflections on Tibet', New Left Review 14, March-April 2002

- ^ Jan Wong, 'TIBET: Life at the top of the world', World Tibet Network News, December 10 1994

- ^ Tsering Shakya, 'Blood in the Snows', New Left Review 15, May-June 2002

- ^ 'Monastic Education in the Gönpa', Conservancy for Tibetan Art & Culture

- ^ Goldstein (1989), p44, n13

- ^ 'Tibet: 6-year old boy missing and over 50 detained in Panchen Lama dispute', Amnesty International, January 18, 1996

- ^ Tibet, Tibet ISBN 1400041007, pp. 278-282

- ^ Warren W. Smith, Tibetan Nation: A History of Tibetan Nationalism and Sino-Tibetan Relations ISBN 0813331552, p. 600

- ^ Black Book ISBN 0674076087, Internment Est:p. 545, (cites Kewly, Tibet p. 255); Tibet Death Est: p. 546

- ^ Yan Hao, 'Tibetan Population in China: Myths and Facts Re-examined', Asian Ethnicity, Volume 1, No. 1, March 2000, p.24

- ^ Amnesty International, 'Who are the Drapchi 14?'

- ^ "China opens world's highest railway". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 2005-07-01. Retrieved 2006-07-01.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "China completes railway to Tibet". BBC News. 2005-10-15. Retrieved 2006-07-04.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Deemed a road to ruin, Tibetans say Beijing rail-way poses latest threat to minority culture". Boston Globe. 2002-08-26. Retrieved 2006-07-04.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "China Opens 1st Train Service to Tibet". Washington Post. 2006-06-30. Retrieved 2006-07-04.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Dalai Lama Urges 'Wait And See' On Tibet Railway". Deutsche Presse Agentur. 2006-06-30. Retrieved 2006-07-04.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

- Allen, Charles (2004). Duel in the Snows: The True Story of the Younghusband Mission to Lhasa. London: John Murray, 2004. ISBN 0-7195-5427-6.

- Bell, Charles (1924). Tibet: Past & Present. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- McKay, Alex (1997). Tibet and the British Raj: The Frontier Cadre 1904-1947. London: Curzon. ISBN 0-7007-0627-5.

- Shakya, Tsering (1999). The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11814-7.

- Smith, Warren W. (Jr.) (1996). Tibetan Nation: A History of Tibetan Nationalism and Sino-Tibetan Relations. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3155-2.

Further reading and media

- Dowman, Keith (1988). The Power-Places of Central Tibet: The Pilgrim's Guide. Routledge & Kegan Paul. London, ISBN 0-7102-1370-0. New York, ISBN 0-14-019118-6.

- Pachen, Ani; Donnely, Adelaide (2000). Sorrow Mountain: The Journey of a Tibetan Warrior Nun. Kodansha America, Inc. ISBN 1-56836-294-3.

- Goldstein, Melvyn C.; with the help of Gelek Rimpoche. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers (1993), ISBN 81-215-0582-8. University of California (1991), ISBN 0-520-07590-0.

- Grunfield, Tom (1996). The Making of Modern Tibet. ISBN 1-56324-713-5.

- Schell, Orville (2000). Virtual Tibet: Searching for Shangri-La from the Himalayas to Hollywood. Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-4381-0.

- Thurman, Robert (2002). Robert Thurman on Tibet. DVD. ASIN B00005Y722.

- Wilby, Sorrel (1988). Journey Across Tibet: A Young Woman's 1900-Mile Trek Across the Rooftop of the World. Contemporary Books. ISBN 0-8092-4608-2.

- Wilson, Brandon (2004). Yak Butter Blues: A Tibetan Trek of Faith. Heliographica. An Imprint of Pilgrim's Tales. ISBN 1-933037-23-7, ISBN 1-933037-24-5.

- Norbu, Thubten Jigme; Turnbull, Colin (1968). Tibet: Its History, Religion and People. Reprint: Penguin Books (1987).

- Stein, R. A. (1962). Tibetan Civilization. First published in French; English translation by J. E. Stapelton Driver. Reprint: Stanford University Press (with minor revisions from 1977 Faber & Faber edition), 1995. ISBN 0-8047-0806-1.

- Samuel, Geoffrey (1993). Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies. Smithsonian ISBN 1-56098-231-4.

See also

- Évariste Régis Huc (Abbé Huc) visited Tibet in 1845-1846, and wrote his observations in Souvenirs d'un voyage dans la Tartarie, le Thibet, et la Chine pendant les années 1844-1846.

- Francis Younghusband led a punitive military expedition to Tibet in 1904.

- Alexandra David-Neel visited Lhasa in 1924, and wrote several books about the country and its culture.

- International Tibet Independence Movement

- List of active autonomist and secessionist movements

- Tibetan American

- Seven Years in Tibet

- Kundun

- Tibetan Buddhism

- South Tibet

External links

Template:IndicText Template:ChineseText

This page or section may contain link spam masquerading as content. |

Against PRC rule and/or policies in Tibet

- PRC Attacks on Buddhist Monks

- Tibetan Government in Exile's Official Web Site

- Amnesty International Report 2004

- Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy

- Beefy's Nepal and Tibet Page - photos and information on Tibet (and Nepal)

- Better World Links on Tibet — biggest link collection on Tibet

- Canada Tibet Committee

- Central Tibetan Administration (Government in Exile)

- IFEX: Freedom of expression violations in Tibet

- International Campaign for Tibet

- Tibetan Review (official website of the magazine, incl. numerous articles)

- Faith in Exile - A video by the Guerrilla News Network

- Free Tibet Campaign

- Olympic Watch (Committee for the 2008 Olympic Games in a Free and Democratic Country) on Tibet-related issues

- Physicians for Human Rights

- Repression in Tibet, 1987 - 1992

- Repression in Tibet

- Students for a Free Tibet

- Tibet Online - Tibet Support Group

- Tibetan Studies WWW Virtual Library

- U.S. Tibet Committee

- Voice of Tibet

- Australia-Tibet Council

- The Times of Tibet

- Phayul News & Views on Tibet

For PRC rule and policies in Tibet

- Tibetan History on the China Tibet Information Center of the PRC

- China, Tibet and the Chinese nation

- China Tibet Information Center

- Chinese government white paper, "Tibet's March Toward Modernization" (2001)

- Chinese government white paper "Tibet -- Its Ownership And Human Rights Situation" (1992)

- Naming of Tibet (Traditional Chinese)

- PRC Government Tibet information

- Regional Ethnic Autonomy in Tibet (May 2004)

- Tibet Online (Simplified Chinese)

- Tibet University (Simplified Chinese)

- Tibet Tour (Tibet Tourism Bureau Official Site)

- White Paper on Ecological Improvement and Environmental Protection in Tibet

- White Paper on Tibetan Culture and Homayk

Apolitical

- Haiwei Trails - Timeline of Tibet

- Kham Aid Foundation

- Maps

- Pictures of Tibet

- Photographs

- The Impact of China's Reform Policy on the Nomads of Western Tibet by Melvyn C. Goldstein and Cynthia M. Beall - An examination of the impact of China's post-1980 Tibet policy on a traditional nomadic area of Tibet's Changtang (Northern Plateau) about 300 miles west-north-west of Lhasa in Phala Xiang, Ngamring county.

- Tibetan Support Programme

- The Tibetan and Himalayan Digital Library

- Template:Wikitravel