Indigenous Australian art

Australian Aboriginal art is art done by Australian Aborigines, covering art that pre-dates European colonisation as well as contemporary art by Aborigines based on traditional culture. It includes a wide variety of media including painting, wood carving, sculpture and ceremonial clothing, as well as artistic embellishments found on weaponry and tools.

Art was one of the key rituals of Aboriginal culture and was was used to mark territory, record history, and tell stories.

Aboriginal painting

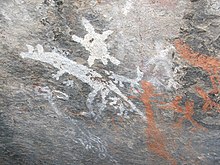

Traditionally, paints were often made from water or spittle mixed with ochre and other rock pigments. Painting was then performed on persons, rock walls or bark (particular that of the paperbark gum). Tools used included primitive brushes, sticks, fingers and even a technique of spraying the paint directly out of the mouth onto the medium resulting in an effect similar to modern spraypaint.

There are a wide variety of styles of Aboriginal art. Three common types are the cross-hatch or X-ray art from the Arnhem Land region of the Northern Territory, in which the skeletons and viscera of the animals and humans portrayed are drawn inside the outline, as if by cross-section; dot-painting where intricate patterns, totems and/or stories are created using dots; and stencil art, particular using the motif of a handprint. More simple designs of straight lines, circles and spirals, with the occasional zig zag persist throughout the work of Australian Aborigines. These are thought to be the origins of "modern" Aboriginal Art.

One type of Aboriginal painting is known as the Bradshaws, some ancient rock art which appears on caves in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. They are named after the European pastoralist, Joseph Bradshaw, who discovered them in 1891. Dampier, Western Australia also has the world's largest collection of petroglyphs, another ancient style of aboriginal art.

Bark painting

The barest necessities for bark artwork are paint, brushes, bark, fixative and a fire. The bark chosen must be free of knots and other blemishes. It is best cut from the tree in the wet season when the sap is rising. Two horizontal slices and a single vertical slice are made into the tree, and the bark is then carefully peeled off with the aid of a sharpened tool. Only the inner smooth bark is kept and placed in a fire. After heating in the fire, the bark is flattened under foot and weighted with stones or logs to dry flat. The "canvas" is then ready to paint upon.

After the painting is completed, the bark is splinted at either end to keep the painting flat. A fixative, traditionally orchid juice, is added over top.

Carvings and sculpture

- Carved shells

- Mimih (or Mimi) small man-like carvings of mythological impish creatures. Mimihs are so frail that they never venture out on windy days lest they be swept away like leaf litter. If approached by men they will run into a rock crevice, if no crevice is there, the rocks themselves will open up and seal behind the Mimih.

- Necklaces and other jewellery, such as those from the Tasmanian Aborigines

- Basket weaving

Other art

Sand designs in desert areas of north and central Australia.

Religious and cultural aspects of Aboriginal art

Traditional Aboriginal art almost always has a mythological undertone relating to the Dreamtime of Australian Aborigines. Many modern purists will say if it doesn't contain the spirituality of aborigines, it is not true aboriginal art.[citation needed] Wenten Rubuntja, an Aboriginal landscape artist says it's hard to find any art that is devoid of spiritual meaning;

"Doesn't matter what sort of painting we do in this country, it still belongs to the people, all the people. This is worship, work, culture. It's all Dreaming. There are two ways of painting. Both ways are important, because that's culture." - source The Weekend Australian Magazine, April, 2002

Story telling and totem representation feature prominently in all forms of Aboriginal artwork. Additionally the female form, particularly the female womb in X-ray style features prominently in some famous sites in Arnhem Land.

Graffiti and other destructive influences

Many culturally significant sites of Aboriginal rock paintings have been gradually desecrated and destroyed by encroachment of early settlers and modern-day visitors. This includes the destruction of art by clearing and construction work, erosion caused by excessive touching of sites, and graffiti. Many sites now belonging to National Parks have to be strictly monitored by rangers, or closed off to the public permanently.

Modern Aboriginal Artists

In 1934 Australian painter Rex Batterbee taught Aboriginal artist Albert Namatjira western style watercolour landscape painting, along with other Aboriginal artists at the Hermannsburg mission in the Northern Territory. It became a popular style, known as the Hermannsburg School, and sold out when the paintings were exhibited in Melbourne, Adelaide and other Australian cities. Namatjira became the first Aboriginal Australian citizen, as a result of his fame and popularity with these watercolour paintings.

In 1966, one of David Malangi's designs was produced on the Australian one dollar note, originally without his knowledge. The subsequent payment to him by the Reserve Bank marked the first case of Aboriginal copyright in Australian copyright law.

In 1971-1972, art teacher Geoffrey Bardon encouraged Aboriginal people in Papunya, north west of Alice Springs to put their Dreamtime stories onto canvases. These stories would previously have been drawn on the desert sand, and were now given a more permament form. Eventually the style, known as the Papunya Tula school, or sometimes popularly as 'dot art', became the most recognisable form of Australian Aboriginal painting. Much of the Aboriginal art on display in tourist shops traces back to this style developed at Papunya. The most famous of the artists to come from this movement was Clifford possum Tjapaltjarri. Also from this movement is Johnny Warangkula, whose Water Dreaming at Kalipinya twice sold at a record price, the second time being $486,500 in 2000.

In 1983, some members of the Papunya movement, concerned and unhappy with the way their paintings were sold to private dealers, moved to Yuendumu and began painting 36 doors at the school there with their dreamtime stories, which started an art movement there. In 1985 the Warlukwlangu artists association was founded at Yuendumu, which co-ordinates the artists in the area. The best-known painter from this movement is Paddy Japaljarri Stewart.

In 1988 an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander memorial was unveiled at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra made from 200 hollow log coffins, which are similar to the type used for mortuary ceremonies in Arnhem Land. It was made for the bicentenary of Australia's colonisation, and is in remembrance of Aboriginal people who had died protecting their land during conflict with settlers. Made by 43 artists from Ramingining and communities nearby. The path running through the middle of it represents the Glyde River.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the work of Emily Kngwarreye became very popular. Although she had been involved in craftwork for most of her life, it was only when she was in her 80s that she was recognised as a painter. She was from the Utopia community north east of Alice Springs. The period of her life when she was painting was only for a few years near the end of her life. Her styles which changed every year, have been seen as a mixture of traditional Aboriginal and contemporary Australian.

Rover Thomas is another well known modern Australian Aboriginal artist. Born in Western Australia, he represented Australia in the Venice Biennale of 1991. He knew and encouraged another well known artist to paint, Queenie McKenzie, from the East Kimberley / Warmun region.

Exploitation of Artists

There have been cases of some exploitative dealers (known as carpetbaggers) that have sought to profit from the success of the Aboriginal art movements. Since Geoffrey Bardon's time and in the early years of the Papunya movement, there has been concerns about the exploitation of the largely illiterate and non-English speaking artists.

One of the main reasons the Yuendumu movement was established, and later flourished, was due to the feeling of exploitation amongst artists:

"Many of the artists who played crucial roles in the founding of the art centre were aware of the increasing interest in Aboriginal art during the 1970s and had watched with concern and curiosity the developments of the art movement at Papunya amongst people to whom they were closely related. There was also a growing private market for Aboriginal art in Alice Springs. Artists' experiences of the private market were marked by feelings of frsutration and a sense of desempowerment when buyers refused to pay prices which reflected the value of the Jukurrpa or showed little interest in understanding the story. The establishment of Warlukurlangu was one way of ensuring the artists had some control over the purchase and distribution of their paintings." (Source: Warlukurlangu Artists)

In September 2003, Melbourne art dealers Tony and Alexis Hesseen of the Original and Authentic Aboriginal Art (with shops in Bourke Street and The Rocks, Sydney) brought a group of central Australian Aboriginal artists including Adrian Young, Marlene Young, Debra Young and Annie Farmer to a house in the Dandenong region to produce 62 paintings with a market value of AUD134,000. In return, the group were paid a mere fraction of that at AUD7,000. The group was discovered after seeking help from neighbours complaining of cold and illness. In the ensuing uproar, it was revealed the Hesseens produced an affadvit urging Marlene and Adrian Young to sign it stating "We regret telling the media lies and apologise to the [Hesseens] for the problems we caused them...[we were] taken to Red Rooster for dinner and [taken to] K-Mart where we all received warm clothing and shoes appropriate for the Melbourne weather." (Source: Ian Munro (2003) A grim picture, say Aboriginal artists of their city stay, The Age, September 12; Gabrielle Coslovich (2003) Aboriginal works and artful dodgers, The Age, September 20, and Anger over cash offer to black artists, The Age, October 23)

The same dealers also brought Mt Liebig artist Mitjili Napurulla, wife to a famous artist then-septuagenarian Long Tom Tjapanangka to Melbourne to paint for them. According to Mt Liebig art coordinator Glenis Wilkins, local tribal law dictated Mitjili be severely beaten for abandoning him if he died while she was away. Tony Hesseen said "We spent $637 on clothing from St. Vincent de Paul for them." (Source: Ian Munro (2003) A grim picture, say Aboriginal artists of their city stay, The Age, September 12)

Other cases of exploitation include:

- painting for a lemon (car): "Artists have come to me and pulled out photos of cars with mobile phone numbers on the back. They're asked to paint 10-15 canvasses in exchange for a car. When the 'Toyotas' materalise, they often arrive with a flat tyre, no spares, no jack, no fuel." (Munro 2003)

- preying on a sick artist: "Even coming to town for medical treatment, such as dialysis, can make an artist easy prey for dealers wanting to make a quick profit who congregate in Alice Springs" (op.cit.)

- pursuing a famous artist: "The late (great) [[Emily Kame Kngwarreye...was relentlessly pursued by carpetbaggers towards the end of her career and produced a large but inconsistent body of work." According to Sotheby's "We take about one in every 20 paintings of hers, and with those we look for provenance we can be 100% sure of." (op.cit.)

List of contemporary Aboriginal artists

- Albert Namatjira

- Wenten Rubuntja

- Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri

- Dorothy Napangardi

- Rover Thomas

- Naata Nungurrayi

- Emily Kngwarreye

- Paddy Japaljarri Stewart

Famous sites of Aboriginal art

These are the most significant sites.

See also

Aboriginal Art Movements and Co-operatives

- Balgo / Warlayirti Artists

- Papunya Tula

- Warmun (Turkey Creek) Gija Artists

- Yuendumu / Warlukurlangu Artists

External links

- ABC News Indigenous Australian Visual Arts and Artists

- Meaning of symbols found in Aboriginal art

- Information about many Central Australian artists, in English and German

- Germaine Greer on Aboriginal art

- Oscar's sketchbook -- pencil drawings by a young Aboriginal man in the late 1800s at the National Museum of Australia