Che Guevara

| Ernesto Guevara de la Serna | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 14, 1928 Rosario, Argentina |

| Died | October 9, 1967 La Higuera, Bolivia |

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna (June 14, 1928 – October 9, 1967), commonly known as Che Guevara or el Che, was an Argentine-born Marxist, politician, and leader of Cuban and internationalist guerrillas. As a young man studying medicine, Guevara traveled rough throughout Latin America, bringing him into direct contact with the impoverished conditions in which many people live. Through these experiences he became convinced that only revolution could remedy the region's economic inequality, leading him to study Marxism and become involved in Guatemala's social revolution under President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán.

Guevara joined Fidel Castro's paramilitary 26th of July Movement, which seized power in Cuba in 1959. After serving in various important posts in the new government and writing a number of articles and books on the theory and practice of guerrilla warfare, Guevara left Cuba in 1965 with the intention of fomenting revolutions first in Congo-Kinshasa, and then in Bolivia, where he was captured in a CIA/ U.S. Army Special Forces-organized military operation.[1] Guevara died at the hands of the Bolivian Army in La Higuera near Vallegrande on October 9, 1967. Participants in, and witnesses to, the events of his final hours testify that his captors executed him without trial.

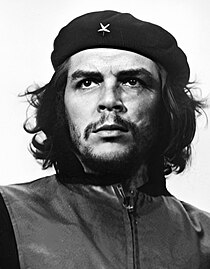

After his death, Guevara became an icon of socialist revolutionary movements worldwide. An Alberto Korda photo of Guevara (shown) has received wide distribution and modification. The Maryland Institute College of Art called this picture "the most famous photograph in the world and a symbol of the 20th century."[2]

Family heritage and early life

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna was born in Rosario, Argentina, the eldest of five children in a family of mixed Spanish and Irish descent; both his father and mother were of Basque ancestry.[Basque] The date of birth recorded on his birth certificate was June 14, 1928, although one tertiary source (Julia Constenla, quoted by Jon Lee Anderson) asserts that he was actually born on May 14 of that year. (Constenla alleges that she was told by an unidentified astrologer that his mother, Celia de la Serna, was already pregnant when she and Ernesto Guevara Lynch were married and that the birthdate of their son was forged a month later than the actual date to avoid scandal.)[3] One of Guevara's forebears, Patrick Lynch, was born in Galway, Ireland, in 1715. He left for Bilbao, Spain, and traveled from there to Argentina. Francisco Lynch (Guevara's great-grandfather) was born in 1817, and Ana Lynch (his beloved grandmother) in 1868[Galway] Her son, Ernesto Guevara Lynch (Guevara's father) was born in 1900. Guevara Lynch married Celia de la Serna y Llosa in 1927, and they had three sons and two daughters.

In this upper-class family with leftist leanings, Guevara became known for his dynamic personality and radical perspective even as a boy. Though suffering from the crippling bouts of asthma that were to afflict him throughout his life, he excelled as an athlete. He was an avid rugby union player despite his handicap and earned himself the nickname "Fuser" — a contraction of "El Furibundo" (English: "The Raging") and his mother's surname, "Serna" — for his aggressive style of play.[4]

Guevara learned chess from his father and began participating in local tournaments by the age of 12.[5] During his adolescence he became passionate about poetry, especially that of Pablo Neruda[Neruda]. Guevara, as is common practice among Latin Americans of his class, also wrote poems throughout his life. He was an enthusiastic and eclectic reader, with interests ranging from adventure classics by Jack London and Jules Verne to essays on sexuality by Sigmund Freud and treatises on social philosophy by Bertrand Russell. In his late teens, he developed a keen interest in photography and spent many hours photographing people, places and, during later travels, archaeological sites.

In 1948 Guevara entered the University of Buenos Aires to study medicine. While a student, he spent long periods traveling around Latin America. In 1951 his older friend, Alberto Granado, a biochemist, suggested that Guevara take a year off from his medical studies to embark on a trip they had talked of making for years, traversing South America. Guevara and the 29-year-old Granado soon set off from their hometown of Alta Gracia astride a 1939 Norton 500 cc motorcycle they named La Poderosa II (English: "the Mighty One, the Second") with the idea of spending a few weeks volunteering at the San Pablo Leper colony in Peru on the banks of the Amazon River. Guevara narrated this journey in The Motorcycle Diaries, which was translated into English in 1996 and used in 2004 as the basis for a motion picture of the same name.

Through his firsthand observations of the poverty, oppression and powerlessness of the masses, and influenced by his informal Marxist studies, Guevara concluded that the only solution for Latin America's economic and social inequities lay in armed revolution. His travels also inspired him to look upon Latin America not as a collection of separate nations but as a single entity, the liberation of which would require a continent-wide strategy; he began to imagine the possibility of a united Ibero-America without borders, bound together by a common 'mestizo' culture,[Ibero-America] an idea that would figure prominently in his later revolutionary activities. Upon his return to Argentina, he completed his medical studies as quickly as he could in order to continue his travels around South and Central America, and received his diploma on 12 June 1953.[Diploma]

Guatemala

On 7 July 1953, Guevara set out on a trip through Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, and El Salvador. During the final days of December 1953 he arrived in Guatemala where President Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán headed a populist government that, through land reform and other initiatives, was attempting to bring about a social revolution. In a letter to his Aunt Beatriz, Guevara explained his motivation for settling down for a time in Guatemala: "In Guatemala", he wrote, "I will perfect myself and accomplish whatever may be necessary in order to become a true revolutionary."[6]

Shortly after reaching Guatemala City, Guevara acted upon the suggestion of a mutual friend that he seek out Hilda Gadea Acosta, a Peruvian economist who was living and working there. Gadea, whom he would later marry, was well-connected politically as a result of her membership in the socialist American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA) led by Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre, and she introduced Guevara to a number of high-level officials in the Arbenz government. He also re-established contact with a group of Cuban exiles linked to Fidel Castro whom he had initially met in Costa Rica; among them was Antonio "Ñico" López, associated with the attack on the "Carlos Manuel de Céspedes" barracks in Bayamo in the Cuban province of Oriente,[7] and who would die at Ojo del Toro bridge soon after the Granma landed in Cuba.[8] Guevara joined these "moncadistas" in the sale of religious objects related to the Black Christ, and he also assisted two Venezuelan malaria specialists at a local hospital. It was during this period that he acquired his famous nickname, "Che", due to his frequent use of the Argentine interjection Che (pronounced /tʃe/), which is utilized in much the same way as "hey", "pal", "eh", or "mate" are employed colloquially in various English-speaking countries. Argentina, Uruguay, and southern Brazil (where the interjection is rendered 'chê' or 'ché' in written Portuguese) are the only areas where this expression is used, making it a trademark of the Rioplatense region.

Guevara's attempts to obtain a medical internship were unsuccessful and his economic situation was often precarious, leading him to pawn some of Hilda's jewelry. Political events in the country began to move quickly after May 15, 1954 when a shipment of Skoda infantry and light artillery weapons sent from Communist Czechoslovakia for the Arbenz Government arrived in Puerto Barrios aboard the Swedish ship Alfhem. The amount of Czech weaponry was estimated to be 2000 tons by the CIA[9] though only 2 tons by Jon Lee Anderson.[10] (Anderson's tonnage estimate is thought to be a typographical error due to how few scholarly sources support it.) Guevara briefly left Guatemala for El Salvador to pick up a new visa, then returned to Guatemala only a few days before the CIA-sponsored coup attempt led by Carlos Castillo Armas began.[11] The anti-Arbenz forces tried, but failed, to stop the trans-shipment of the Czechoslovak weapons by train; nevertheless, after pausing to regroup and recover energy, and apparently with the assistance of air support provided by the USA, they started to gain ground.[12] Guevara was eager to fight on behalf of Arbenz and joined an armed militia organized by the Communist Youth for that purpose; but, frustrated with the group's inaction, he soon returned to medical duties. Following the coup, he again volunteered to fight; however, Arbenz took refuge in the Mexican Embassy and told his foreign supporters to leave the country and, after Gadea was arrested, Guevara sought protection in the Argentine consulate where he remained until he received a safe-conduct pass some weeks later. At that point, he turned down a free seat on a flight back to Argentina that was proffered to him by the Embassy, preferring instead to make his way to Mexico.

The overthrow of the Arbenz regime by a coup d'état backed by the Central Intelligence Agency cemented Guevara's view of the United States as an imperialist power that would implacably oppose and attempt to destroy any government that sought to redress the socioeconomic inequality endemic to Latin America and other developing countries. This strengthened his conviction that socialism achieved through armed struggle and defended by an armed populace was the only way to rectify such conditions.

Cuba

The tank is a Sherman with a 76 mm cannon. [2]

(1 January 1959)

Guevara arrived in Mexico City in early September 1954, and shortly thereafter renewed his friendship with Ñico López and the other Cuban exiles whom he had known in Guatemala. In June 1955, López introduced him to Raúl Castro. Several weeks later, Fidel Castro arrived in Mexico City after having been released from political prison in Cuba, and on the evening of 8 July 1955 Raúl introduced Guevara to him. During a fervid overnight conversation, Guevara became convinced that Castro was the inspirational revolutionary leader for whom he had been searching, and he immediately joined the "26th of July Movement" that intended to overthrow the government of Fulgencio Batista. Although it was planned that he would be the group's medic, Guevara participated in the military training along with the other members of the 26J Movement, and at the end of the course was singled out by their instructor, Col. Alberto Bayo, as his most outstanding student. Meanwhile, Gadea had arrived from Guatemala and she and Guevara resumed their relationship. In the summer of 1955 she informed him that she was pregnant and he immediately suggested that they marry. The wedding took place on August 18, 1955, and their daughter, whom they named Hilda Beatríz, was born on February 15, 1956.[13]

When the cabin cruiser Granma set out from Tuxpan, Veracruz for Cuba on November 25, 1956, Guevara was the only non-Cuban aboard. Attacked by Batista's military soon after landing, about half of the expeditionaries were killed or executed upon capture. Guevara writes that it was during this confrontation that he laid down his knapsack containing medical supplies in order to pick up a box of ammunition dropped by a fleeing comrade, a moment which he later recalled as marking his transition from physician to combatant.[Knapsack] Only 15–20 rebels survived as a battered fighting force; they re-grouped and fled into the mountains of the Sierra Maestra to wage guerrilla warfare against the Batista regime.

Guevara became a leader among the rebels, a Comandante (English translation: Major), respected by his comrades in arms for his courage and military prowess,[14] and feared for what some have described as "ruthlessness": he was responsible for the execution of many men accused of being informers, deserters or spies. In the final days of December 1958, he directed the attack led by his "suicide squad" (which undertook the most dangerous tasks in the rebel army)[15] on Santa Clara which was one of the decisive events of the revolution, although the bloody series of ambushes first during la ofensiva in the heights of the Sierra Maestra, then at Guisa, and the whole Cauto Plains campaign that followed probably had more military significance. Batista, upon learning that his generals — especially General Cantillo, who had visited Castro at the inactive sugar mill "Central America" — were negotiating a separate peace with the rebel leader, fled to the Dominican Republic on January 1, 1959.

On February 7, 1959, the victorious government proclaimed Guevara "a Cuban citizen by birth." Shortly thereafter, he initiated divorce proceedings to put a formal end to his marriage with Gadea, from whom he had been separated since before leaving Mexico on the Granma, and on June 2, 1959, he married Aleida March,[Children] a Cuban-born member of the 26th of July movement with whom he had been living since late 1958.

He was appointed commander of the La Cabaña Fortress prison, and during his six-month tenure in that post (January 2 through June 12, 1959),[16] he oversaw the trial and execution of many people some of whom were former Batista regime officials, members of the BRAC (Buró de Represión de Actividades Comunistas, "Bureau for the Repression of Communist Activities") secret police, alleged war criminals, and political dissidents. The trials he conducted were alleged to be "unfair", according to Time Magazine.[17] Later, Guevara became an official at the National Institute of Agrarian Reform,[INRA] and President of the National Bank of Cuba[BNC] (somewhat ironically, as he often condemned money, favored its abolition, and showed his disdain by signing Cuban banknotes with his nickname, "Che").[Signature]

During this time his fondness for chess was rekindled, and he attended and participated in most national and international tournaments held in Cuba.[18][19] He was particularly eager to encourage young Cubans to take up the game, and organized various activities designed to stimulate their interest in it.

Even as early as 1959, Guevara helped organize revolutionary expeditions overseas, all of which failed. The first attempt was made in Panama; another in the Dominican Republic (led by Henry Fuerte,[20] also known as "El Argelino", and Enrique Jiménez Moya)[21] took place on 14 June of that same year.

(Havana - April 1961)

In 1960 Guevara provided first aid to victims during the La Coubre arms shipment rescue operation that went further awry when a second explosion occurred, resulting in well over a hundred dead.[22] It was at the memorial service for the victims of this explosion that Alberto Korda took the most famous photograph of him. Whether La Coubre was sabotaged or merely exploded by accident is not clear. Those who favour the sabotage theory sometimes attribute this to the Central Intelligence Agency[23] and sometimes name William Alexander Morgan,[24] a former rival of Guevara's in the anti-Batista forces of the central provinces and later a putative CIA agent, as the perpetrator. Cuban exiles have put forth the theory that it was done by Guevara's USSR-loyalist rivals.[25]

Guevara later served as Minister of Industries,[MININD] in which post he helped formulate Cuban socialism, and became one of the country's most prominent figures. In his book Guerrilla Warfare, he advocated replicating the Cuban model of revolution initiated by a small group (foco) of guerrillas without the need for broad organizations to precede armed insurrection. His essay El socialismo y el hombre en Cuba (1965) (Man and Socialism in Cuba) advocates the need to shape a "new man" (hombre nuevo) in conjunction with a socialist state. Some saw Guevara as the simultaneously glamorous and austere model of that "new man."

During the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion, Guevara did not participate in the fighting, having been ordered by Castro to a command post in Cuba's westernmost Pinar del Río province where he was involved in fending off a decoy force. He did, however, suffer a bullet wound to the face during this deployment, which he said had been caused by the accidental firing of his own gun.[26]

Guevara played a key role in bringing to Cuba the Soviet nuclear-armed ballistic missiles that precipitated the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. During an interview with the British newspaper Daily Worker some weeks later, he stated that, if the missiles had been under Cuban control, they would have fired them against major U.S. cities.[27]

Disappearance from Cuba

(New York City - 11 December 1964)

In December 1964 Che Guevara traveled to New York City as the head of the Cuban delegation to speak at the UN (listen, requires RealPlayer; or read). He also appeared on the CBS Sunday news program Face the Nation, met with a gamut of individuals and groups including U.S. Senator Eugene McCarthy, several associates of Malcolm X, and Canadian radical Michelle Duclos,[28] and dined at the home of the Rockefellers.[29] On 17 December, he flew to Paris and from there embarked on a three-month international tour during which he visited the People's Republic of China, the United Arab Republic (Egypt), Algeria, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Dahomey, Congo-Brazzaville and Tanzania, with stops in Ireland, Paris and Prague. In Algiers on 24 February, 1965, he made what turned out to be his last public appearance on the international stage when he delivered a speech to the "Second Economic Seminar on Afro-Asian Solidarity" in which he declared, "There are no frontiers in this struggle to the death. We cannot remain indifferent in the face of what occurs in any part of the world. A victory for any country against imperialism is our victory, just as any country's defeat is our defeat."[30] He then astonished his audience by proclaiming, "The socialist countries have the moral duty of liquidating their tacit complicity with the exploiting countries of the West." He proceeded to outline a number of measures which he said the communist-bloc countries should implement in order to accomplish this objective.[31][32] He returned to Cuba on 14 March to a solemn reception by Fidel and Raúl Castro, Osvaldo Dorticós and Carlos Rafael Rodríguez at the Havana airport.

Two weeks later, Guevara dropped out of public life and then vanished altogether. His whereabouts were the great mystery of 1965 in Cuba, as he was generally regarded as second in power to Castro himself. His disappearance was variously attributed to the relative failure of the industrialization scheme he had advocated while minister of industry, to pressure exerted on Castro by Soviet officials disapproving of Guevara's pro-Chinese Communist bent as the Sino-Soviet split grew more pronounced, and to serious differences between Guevara and the Cuban leadership regarding Cuba's economic development and ideological line. Others suggested that Castro had grown increasingly wary of Guevara's popularity and considered him a potential threat. Castro's critics sometimes say his explanations for Guevara's disappearance have always been suspect (see below), and many found it surprising that Guevara never announced his intentions publicly, but only through an undated and uncharacteristically obsequious letter to Castro.

The coincidence of Guevara's views with those expounded by the Chinese Communist leadership became increasingly problematic for Cuba as the nation's economic dependence on the Soviet Union deepened. Since the early days of the Cuban revolution, Guevara had been considered by many an advocate of Maoist strategy in Latin America and the originator of a plan for the rapid industrialization of Cuba which was frequently compared to China's "Great Leap Forward". According to Western "observers" of the Cuban situation, the fact that Guevara was opposed to Soviet conditions and recommendations that Castro seemed obliged to accept might have been the reason for his disappearance. However, both Guevara and Castro were supportive of the idea of a "united anti-imperialist front" intended to include both the Soviet Union and China, and had made several unsuccessful attempts to reconcile the feuding parties.

(Havana - 14 March 1965)

Following the Cuban Missile Crisis and what he perceived as a Soviet betrayal of Cuba when Khrushchev agreed to withdraw the missiles from Cuban territory without consulting Castro, Guevara had grown more skeptical of the Soviet Union. As revealed in his last speech in Algiers, he had come to view the Northern Hemisphere, led by the U.S. in the West and the Soviet Union in the East, as the exploiter of the Southern Hemisphere. He strongly supported Communist North Vietnam in the Vietnam War, and urged the peoples of other developing countries to take up arms and create "many Vietnams".[33]

Pressed by international speculation regarding Guevara's fate, Castro stated on 16 June, 1965, that the people would be informed about Guevara when Guevara himself wished to let them know. Numerous rumors about his disappearance spread both inside and outside Cuba. On 3 October of that year, Castro revealed an undated letter[34] purportedly written to him by Guevara some months earlier in which Guevara reaffirmed his enduring solidarity with the Cuban Revolution but declared his intention to leave Cuba to fight abroad for the cause of the revolution. He explained that "Other nations of the world summon my modest efforts," and that he had therefore decided to go and fight as a guerrilla "on new battlefields". In the letter Guevara announced his resignation from all his positions in the government, in the party, and in the Army, and renounced his Cuban citizenship, which had been granted to him in 1959 in recognition of his efforts on behalf of the revolution.

During an interview with four foreign correspondents on 1 November, Castro remarked that he knew where Guevara was but would not disclose his location, and added, denying reports that his former comrade-in-arms was dead, that "he is in the best of health." Despite Castro's assurances, Guevara's fate remained a mystery at the end of 1965 and his movements and whereabouts continued to be a closely held secret for the next two years.

Congo

Expedition

During their all-night meeting on March 14–March 15, 1965, Guevara and Castro had agreed that the former would personally lead Cuba's first military action in Sub-Saharan Africa.[Algeria] Some usually reliable sources state that Guevara persuaded Castro to back him in this effort, while other sources of equal reliability maintain that Castro convinced Guevara to undertake the mission, arguing that conditions in the various Latin American countries that had been under consideration for the possible establishment of guerrilla focos were not yet optimal.[35] Castro himself has said the latter is true.[36] According to Ahmed Ben Bella, who was president of Algeria at the time and had recently held extended conversations with Guevara, "The situation prevailing in Africa, which seemed to have enormous revolutionary potential, led Che to the conclusion that Africa was imperialism’s weak link. It was to Africa that he now decided to devote his efforts."[37]

The Cuban operation was to be carried out in support of the pro-Patrice Lumumba Marxist Simba movement in the Congo-Kinshasa (formerly Belgian Congo, later Zaire and currently the Democratic Republic of the Congo). Guevara, his second-in-command Victor Dreke, and twelve of the Cuban expeditionaries arrived in the Congo on 24 April 1965; a unit of 100 Afro-Cubans joined them soon afterwards.[38][39] They collaborated for a time with guerrilla leader Laurent-Désiré Kabila,[Kabila] who helped Lumumba supporters lead a revolt that was suppressed in November of that same year by the Congolese army. Guevara dismissed Kabila as insignificant. "Nothing leads me to believe he is the man of the hour," Guevara wrote.[40]

Although Guevara was 37 at the time and had no formal military training, he had the experiences of the Cuban revolution, including his successful march on Santa Clara, which was central to Batista finally being overthrown by Castro's forces. His asthma had prevented him from being drafted into military service in Argentina, a fact of which he was proud given his opposition to the Perón government.

South African mercenaries including Mike Hoare and Cuban exiles worked with the Congolese army to thwart Guevara. They were able to monitor Guevara's communications, arrange to ambush the rebels and the Cubans whenever they attempted to attack, and interdict Guevara's supply lines.[41][42] Guevara's aim was to export the Cuban Revolution by instructing local Simba fighters in communist ideology and strategies of guerrilla warfare. The incompetence, intransigence, and infighting of the local Congolese forces are cited by Guevara in his Congo Diary as the key reasons for the revolt's failure.[43] Later that same year, ill, suffering from his asthma, and disheartened after seven months of frustrations, Guevara left the Congo with the Cuban survivors (six members of his column had died). At one point Guevara had considered sending the wounded back to Cuba, then standing alone and fighting until the end in the Congo as a revolutionary example; however, after being urged by his comrades in arms and pressured by two emissaries sent by Castro, at the last moment he reluctantly agreed to leave the Congo. A few weeks later, when writing the preface to the diary he had kept during the Congo venture, he began it with the words: "This is the history of a failure."[44]

Interlude

Because Castro had made public Guevara's "farewell letter"[45] to him — a letter Guevara had intended should only be revealed in case of his death — wherein he had written that he was severing all ties to Cuba in order to devote himself to revolutionary activities in other parts of the world, he felt that he could not return to Cuba with the other surviving combatants for moral reasons, and he spent the next six months living clandestinely in Dar-es-Salaam, and Prague. During this time he compiled his memoirs of the Congo experience, and wrote the drafts of two more books, one on philosophy[46] and the other on economics.[47] He also visited several countries in Western Europe in order to "test" a new false identity and the corresponding documentation (passport, etc.) created for him by Cuban Intelligence that he planned to use to travel to South America. Throughout this period Castro continued to importune him to return to Cuba, but Guevara only agreed to do so when it was understood that he would be there on a strictly temporary basis for the few months needed to prepare a new revolutionary effort somewhere in Latin America, and that his presence on the island would be cloaked in the tightest secrecy.

Bolivia

Insurgent

Speculation on Guevara's whereabouts continued throughout 1966 and into 1967. Representatives of the Mozambican independence movement FRELIMO reported meeting with Guevara in late 1966 or early 1967 in Dar es Salaam, at which point they rejected his offer of aid in their revolutionary project.[48] In a speech at the 1967 May Day rally in Havana, the Acting Minister of the armed forces, Maj. Juan Almeida, announced that Guevara was "serving the revolution somewhere in Latin America". The persistent reports that he was leading the guerrillas in Bolivia were eventually shown to be true.

At Castro's behest, a 3,700 acre parcel of jungle land in the remote Ñancahuazú region had been purchased by native Bolivian Communists for Guevara to use as a training area and base camp [Camp]. The evidence suggests that the training at this camp in the Ñancahuazú valley was more hazardous than combat to Guevara and the Cubans accompanying him. Little was accomplished in the way of building a guerrilla army. Former Stasi operative Haydée Tamara Bunke Bider, better known by her nom de guerre "Tania", who had been installed as his primary agent in La Paz, was reportedly also working for the KGB and is widely inferred to have unwittingly served Soviet interests by leading Bolivian authorities to Guevara's trail.[49] The numerous photographs taken by and of Guevara and other members of his guerrilla group that they left behind at their base camp after the initial clash with the Bolivian army in March 1967 provided President René Barrientos with the first proof of his presence in Bolivia; after viewing them, Barrientos allegedly stated that he wanted Guevara's head displayed on a pike in downtown La Paz. He thereupon ordered the Bolivian Army to hunt Guevara and his followers down.

Guevara's guerrilla force, numbering about 50 and operating as the ELN (Ejército de Liberación Nacional de Bolivia; English: "National Liberation Army of Bolivia"), was well equipped and scored a number of early successes against Bolivian regulars in the difficult terrain of the mountainous Camiri region. In September, however, the Army managed to eliminate two guerrilla groups, reportedly killing one of the leaders.

Despite the violent nature of the conflict, Guevara gave medical attention to all of the wounded Bolivian soldiers whom the guerrillas took prisoner, and subsequently released them. Even after his last battle at the Quebrada del Yuro, in which he had been wounded, when he was taken to a temporary holding location and saw there a number of Bolivian soldiers who had also been wounded in the fighting, he offered to give them medical care. (His offer was turned down by the Bolivian officer in charge.)[50]

Guevara's plan for fomenting revolution in Bolivia appears to have been based upon a number of misconceptions:

- He had expected to deal only with the country's military government and its poorly trained and equipped army. However, after the U.S. government learned of his location, CIA and other operatives were sent into Bolivia to aid the anti-insurrection effort. The Bolivian Army was being trained and supplied by U.S. Army Special Forces[USMilitary] advisors, including a recently organized elite battalion of Rangers trained in jungle warfare that set up camp in La Esperanza, a small settlement close to the guerrillas' zone of operations.[51][52]

- Guevara had expected assistance and cooperation from the local dissidents. He did not receive it; and Bolivia's Communist Party, under the leadership of Mario Monje, was oriented towards Moscow rather than Havana and did not aid him, despite having promised to do so. (Some members of the Bolivian Communist Party did join/support him, such as Coco and Inti Peredo, Rodolfo Saldaňa, Serapio Aquino Tudela, and Antonio Jiménez Tardio, against the Party leadership's wishes.)

- He had expected to remain in radio contact with Havana. However, the two shortwave transmitters provided to him by Cuba were faulty, so that the guerrillas were unable to communicate with Havana. (In this, and in many other respects, Manuel Piñeiro, the man to whom Castro had assigned the task of coordinating support for Guevara's operations in Bolivia, performed abysmally.) To further complicate matters, some months into the campaign, the tape recorder that the guerrillas used to record and decode radio messages sent to them from Havana was lost while crossing a river, making de-ciphering such messages more difficult.[Message]

In addition, his penchant for confrontation rather than compromise appears to have contributed to his inability to develop successful working relationships with local leaders in Bolivia, just as it had in the Congo.[53] This tendency had surfaced during his guerrilla warfare campaign in Cuba as well, but had been kept in check there by the timely interventions and guidance of Castro.[54]

Capture and execution

(La Higuera, Bolivia - 9 October 1967)

The Bolivian Special Forces were notified of the location of Guevara's guerrilla encampment by an informant. On 8 October, the encampment was encircled, and Guevara was captured while leading a detachment with Simeón Cuba Sarabia in the Quebrada del Yuro ravine. He offered to surrender after being wounded in the legs and having his rifle destroyed by a bullet. (His pistol was inexplicably lacking an ammunition magazine.) According to some soldiers present at the capture, during the skirmish as they approached Guevara, he allegedly shouted, "Do not shoot! I am Che Guevara and worth more to you alive than dead."

Barrientos promptly ordered his execution upon being informed of his capture.[Barrientos] Guevara was taken to a dilapidated schoolhouse in the nearby village of La Higuera where he was held overnight. Early the next afternoon he was executed. The executioner was Mario Terán, a sergeant in the Bolivian army who had drawn a short straw and was designated to shoot Guevara. Guevara received multiple shots to the legs, so as to avoid maiming his face for identification purposes and simulate combat wounds in an attempt to conceal his execution. Che Guevara did have some last words before his death; he allegedly said to his executioner, "I know you are here to kill me. Shoot, coward, you are only going to kill a man".[55] His body was lashed to the landing skids of a helicopter and flown to neighboring Vallegrande where it was laid out on a laundry tub in the local hospital and displayed to the press.[56] Photographs taken at that time gave rise to legends such as those of San Ernesto de La Higuera and El Cristo de Vallegrande.[57] After a military doctor surgically amputated his hands, Bolivian army officers transferred Guevara's cadaver to an undisclosed location and refused to reveal whether his remains had been buried or cremated.[Amputation]

The hunt for Guevara in Bolivia was headed by Félix Rodríguez, a CIA agent, who previously had infiltrated into Cuba to prepare contacts with the rebels in the Escambray Mountains and the anti-Castro underground in Havana prior to the Bay of Pigs invasion, and had been successfully extracted from Cuba afterwards.[58][59] Upon hearing of Guevara's capture, Rodríguez relayed the information to CIA headquarters at Langley, Virginia, via CIA stations in various South American nations. After the execution, Rodríguez took Guevara's Rolex watch and several other personal items, often proudly showing them to reporters during the ensuing years. Today, some of these belongings, including his flashlight, are on display at the CIA.

On October 15, Castro acknowledged that Guevara was dead and proclaimed three days of public mourning throughout Cuba. The death of Guevara was regarded as a severe blow to the socialist revolutionary movements throughout Latin America and the rest of the third world.

In 1997, the skeletal remains of Guevara's handless body were exhumed from beneath an air strip near Vallegrande, positively identified by DNA matching, and returned to Cuba. On 17 October, 1997, his remains, along with those of six of his fellow combatants killed during the guerrilla campaign in Bolivia, were laid to rest with full military honors in a specially built mausoleum[Mausoleum] in the city of Santa Clara, where he had won the decisive battle of the Cuban Revolution.

The Bolivian Diary

Also removed when Guevara was captured was his diary, which documented events of the guerrilla campaign in Bolivia.[60] The first entry is on November 7 1966 shortly after his arrival at the farm in Ñancahuazú, and the last entry is on October 7 1967, the day before his capture. The diary tells how the guerrillas were forced to begin operations prematurely due to discovery by the Bolivian Army, explains Guevara's decision to divide the column into two units that were subsequently unable to reestablish contact, and describes their overall failure. It records the rift between Guevara and the Bolivian Communist Party that resulted in Guevara having significantly fewer soldiers than originally anticipated. It shows that Guevara had a great deal of difficulty recruiting from the local populace, due in part to the fact that the guerrilla group had learned Quechua rather than the local language which was Tupí-Guaraní. As the campaign drew to an unexpected close, Guevara became increasingly ill. He suffered from ever-worsening bouts of asthma, and most of his last offensives were carried out in an attempt to obtain medicine.

The Bolivian Diary was quickly and crudely translated by Ramparts magazine and circulated around the world. There are at least four additional diaries — those of Israel Reyes Zayas (Alias "Braulio"), Harry Villegas Tamayo ("Pombo"), Eliseo Reyes Rodriguez ("Rolando")[61] and Dariel Alarcón Ramírez ("Benigno")[62] — each of which reveals additional aspects of the events in question.

Legacy

While pictures of Guevara's dead body were being circulated and the circumstances of his death debated, his legend began to spread. Demonstrations in protest against his execution occurred throughout the world, and articles, tributes, songs and poems were written about his life and death.[63][64] Latin America specialists advising the U.S. State Department immediately recognized the importance of the defeat of “the foremost tactician of the Cuban revolutionary strategy”, noting in 1967 that Guevara’s “heroic death” would have a reaction amongst leftists of whatever stripe, leading them to “eulogize the revolutionary martyr – especially for his contribution to the Cuban revolution - and to maintain that revolutions will continue until their causes are eradicated.”[65]

Such predictions gained increasing credibility as Guevara became a contemporary hero for many, admirers associating his image with struggle, sacrifice and devotion to a cause. His popularity was attributed to the “sincere personality of a man who never stepped back, never sold out and fought passionately, to death”.[66]

Guevara's status as a popular icon symbolizing revolution and left-wing political ideals has continued unabated among youngsters in cultures thoughout the world. A photograph of Guevara taken by photographer Alberto Korda[67] soon became one of the century's most recognizable images, and the portrait, transformed into a monochrome graphic, was reproduced on a vast array of merchandise, such as T-shirts, posters, coffee mugs, and baseball caps.[68] The Neo-Nazi movement in Germany has started wearing shirts bearing Che's portrait,[69][70] despite Guevara's strong opposition to all forms of fascism and racism.[71] Posters and apparel bearing his image were also prominent during the marches to protest U.S. immigration policy that took place in Los Angeles and other cities in Spring 2006.[72]

Guevara's reputation even extended into theater, where he is depicted as the narrator in Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber's musical Evita. This portrays Guevara as becoming disillusioned with Eva Perón and her husband, President Juan Domingo Perón, because of Perón's increasing corruption and tyranny. The narrator role involves creative license, because Guevara's only interaction with Eva Perón was to write her a letter in his youth asking for a Jeep.

During the shift to the left in Latin American politics in recent years, the image of Che has continued to represent the ideals of anti-imperialism and revolutionary liberation that permeate the region. At the November 2005 Summit of the Americas in Mar del Plata, Argentina, the Cuban contingent—one of the largest and best organized delegations protesting the event—produced a large banner with the flags of Latin American countries with Che's face painted over them.[73]

Some 205,832 people visited Guevara's mausoleum in 2004, of whom 127,597 were foreigners. Among the tourists visiting the site were people from Argentina, Canada, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Mexico, South Africa, the United States, and Venezuela.

Guevara was called "the most complete human being of our age" by Jean-Paul Sartre.[74] Guevara's supporters believe he may yet prove to be the most important thinker and activist in Latin America since Simón Bolívar, leader of the South American independence movement and hero to subsequent generations of nationalists throughout Latin America.

Popular culture

Criticism

Though he has been labeled by some as a hero, opponents of Guevara, including most of the Cuban exile community as well as refugees from other countries under communism, view him as a killer and terrorist. New York Sun writer, Williams Myers, labels Che as a “sociopathic thug”. Other US newspaper critics have made similar remarks. These critics point out that Che Guevara was "personally responsible" for the torture and execution of hundreds of people in Cuban prisons, and the murder of many more peasants in the regions controlled or visited by his guerrilla forces. They also believe that Guevara was a blundering tactician, not a revolutionary genius, who has not one recorded combat victory. Some critics also believe that Che failed medical school in Argentina and that there is no evidence he actually ever earned a medical degree. [3] ,[4], [5], [6], [7],[8],[9] Guevara founded Cuba's forced labor camp system, establishing its first forced labor camp in Guanahacabibes to re-educate managers of state-owned enterprises who were guilty of various violations of "revolutionary ethics".[75] Many years after Guevara's death, Cuba's labor camp system was used to jail dissidents of the Revolution.

In 2005, after Carlos Santana wore a Che shirt to the Academy Awards Ceremony, Cuban-born musician Paquito D'Rivera wrote an open letter castigating Santana for supporting "The Butcher of the Cabaña." The Cabaña is the name of a prison where Guevara oversaw the execution of many dissidents, including D'Rivera's own cousin, who, according to D'Rivera, was imprisoned there for being a Christian and witnessed the executions of many Christians at the prison.[76]

Detractors argue that while much propaganda depicts him as a formidable warrior, Guevara was a poor tactician. Empirically, Guevara was a failure at managing the Cuban economy, as he "oversaw the near-collapse of sugar production, the failure of industrialization, and the introduction of rationing—all this in what had been one of Latin America’s four most economically successful countries since before the Batista dictatorship."[77][78]

In "The Cult of Che",[79] writer Paul Berman critiques the film The Motorcycle Diaries and argues "that modern-day cult of Che" obscures the "tremendous social struggle" currently taking place in Cuba. For example, the article discusses the jailing of dissidents, such as poet and journalist Raúl Rivero, who was eventually freed after worldwide pressure due to a campaign of solidarity by the International Committee for Democracy in Cuba[80] which included Václav Havel, Lech Wałęsa, Árpád Göncz, Elena Bonner and others. Berman claims that in the U.S., where Motorcycle Diaries received standing ovations at the Sundance film festival, the adoration of Che has caused Americans to overlook the plight of dissident Cubans. Although most of the criticism of Guevara and his legacy emanates from the political center or right-wing, there has also been criticism from other political groups such as anarchists and civil libertarians, some of whom consider Guevara an authoritarian, whose goal was the creation of a more bureaucratic state-Stalinist regime.[81]

Timeline

Guevara's published works

In English (translations)

- Back on the Road: A Journey to Central America (Harvill Panther S.), The Harvill Press, paperback, ISBN 0-8021-3942-6.

- Bolivian Diary, Pimlico, paperback, ISBN 0-7126-6457-2

- Che Guevara: Radical Writings on Guerrilla Warfare, Politics and Revolution, Filiquarian Publishing LLC, paperback, ISBN 1-59986-999-3.

- Che Guevara Reader: Writings on Guerrilla Warfare, Politics and History, Ocean Press, paperback

- Che Guevara Speaks, Pathfinder, paperback

- Che Guevara Talks to Young People, Pathfinder, paperback

- Critical Notes on Political Economy, Ocean Press, paperback

- Guerrilla Warfare, Souvenir Press Ltd, paperback, ISBN 0-285-63680-4.

- Our America and Theirs, Ocean Press (AU), paperback, ISBN 1-876175-81-8.

- Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War, Monthly Review Press, paperback, 1998

- Self-Portrait: Che Guevara, Ocean Press, 320pp, paperback, 2005

- Socialism and Man in Cuba: Also Fidel Castro on the Twentieth Anniversary of Guevara's Death, Monad, paperback

- The African Dream: The Diaries of the Revolutionary War in the Congo, Grove Press, paperback.

- The Diary of Che Guevara, Amereon Ltd,

- The Motorcycle Diaries: Notes on a Latin American Journey, Perennial Press, ISBN 0-00-718222-8.

In Spanish

- File:Adobepdfreader7 icon.png Cuadernos de Praga – Guevara's notebooks written during his clandestine stay in Prague in 1966 (PDF)

- File:Adobepdfreader7 icon.png Diario del Che en Bolivia – Guevara's diary of the guerrilla war in Bolivia

- File:Adobepdfreader7 icon.png Obras Escogidas – Guevara's selected works in Spanish, including his most important speeches (PDF)

- File:Adobepdfreader7 icon.png Pasajes de la Guerra Revolucionaria: Congo – Guevara's complete Congo Diary in Spanish, (PDF)

- File:Adobepdfreader7 icon.png Pensamiento y acción – A selection of Guevara's writings in Spanish, including El socialismo y el hombre nuevo (PDF)

See also

Source notes

- ^ Death of Che Guevara National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 5 - Declassified top secret document

- ^ Maryland Institute of Art, referenced at BBC News, "Che Guevara photographer dies", 26 May 2001.Online at BBC News, accessed January 42006.

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, pp. 3 and 769.

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 28.

- ^ Digital Granma Internacional, "Simultaneous chess game on 37th anniversary of Che’s death", 13 October 2004. Online at Granma International English Edition, accessed January 5, 2006.

- ^ Guevara Lynch, Ernesto. Aquí va un soldado de América. Barcelona: Plaza y Janés Editores, S.A., 2000, p. 26. "En Guatemala me perfeccionaré y lograré lo que me falta para ser un revolulcionario auténtico." This statement in a letter written in Costa Rica on 10 December 1953 is important because it proves that, whereas many authors have asserted that Guevara became a revolutionary as a result of witnessing the US-sponsored coup against Arbenz, he had in fact already made the decision to become a revolutionary before arriving in Guatemala and indeed went there for that express purpose.

- ^ Radio Cadena Agramonte, "Ataque al cuartel del Bayamo" Online, accessed February 25 2006

- ^ Granma.cu, "Walking towards sunrise" Online, accessed February 252006

- ^ U.S. Department of State, "Foreign Relations, Guatemala, 1952-1954". Online, accessed March 04 2006

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 144

- ^ U.S. Department of State. "Foreign Relations, Guatemala, 1952-1954". Online, accessed March 04 2006

- ^ Holland, Max."Private Sources of U.S. Foreign Policy: William Pawley and the 1954 Coup d'Etat in Guatemala", Journal of Cold War Studies, Volume 7, Number 4, Fall 2005, pp. 36-73

- ^ Taibo, Paco Ignacio II. Ernesto Guevara, también conocido como el Che, p. 104. See also The Guardian online, Making of a Marxist, Online, in Guevara's words "Since February 15 1956 I am a father: Hilda Beatriz Guevara is my first-born" accessed October 62006.

- ^ U. S. Central Intelligence Agency, "CIA Biographic Register on Ernesto 'Che' Guevara". Online, accessed July 12, 2006."Commander of one of the largest of the five rebel columns (Column 4), he gained a reputation for bravery and military prowess second only to Fidel Castro himself."

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, "Suicide Squad: Example Of Revolutionary Morale (an excerpt from Episodes of the Cuban Revolutionary War - 1956-58). The Militant Online, accessed March 272006.

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 372 and p. 425

- ^ TIME magazine, "The TIME 100: Heroes and Icons". Online accessed June 26, 2006.

- ^ chessgames.com, "Miguel Najdorf vs Ernesto Che Guevara". Online at chessgames.com, accessed January 52006.

- ^ ar.geocities.com/carloseadrake/AJEDREZ/, Ernesto "Che" Guevara – Ajedrez Online, accessed June 292006.

- ^ Puerto Padre website, "Cronologia" (List of anniversaries) Online at Puerto Padre website, accessed January 42006.

- ^ Peña, Emilio Herasme," La Expedición Armada de junio de 1959", 14 June 2004.Online at 'Listín Diario (Dominican Republic), accessed January 42006.

- ^ Cuban Information Archives, "La Coubre explodes in Havana 1960." Online, accessed February 26 2006; pictures can be seen at Cuban site fotospl.com.

- ^ Defensa Nacional, "SABOTAJE AL BUQUE LA COUBRE" Online, accessed February 26 2006

- ^ The Miami Herald, "Dockworker set ship blast in Havana, American claims". Online, accessed February 26, 2006

- ^ Guaracabuya.org, "Recuento Histórico:El porque el PCC ordenó volar el barco "La Coubre".Online, accessed February 26 2006

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, ISBN 0-8021-1600-0, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 508.

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, ISBN 0-8021-1600-0, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 545: "In an interview with Che a few weeks after the crisis, Sam Russell, a British correspondent for the socialist Daily Worker, found Guevara still fuming over the Soviet betrayal. Alternately puffing on a cigar and taking blasts from an inhaler, Guevara told Russell that if the missiles had been under Cuban control, they would have fired them off. Russell came away with mixed feelings about Che, calling him 'a warm character whom I took to immediately... clearly a man of great intelligence though I thought he was crackers from the way he went on about the missiles.'"

- ^ Montreal Gazette, "Liberals picked the wrong issue". Online, accessed February 26 2006

‡ Guaracabuya.org, "TERRORISTS CONNECTED TO CUBAN COMMUNIST GOVERNMENT". Online, accessed February 26 2006 - ^ Gálvez, William. Che in Africa: Che Guevara's Congo Diary. Melbourne: Ocean Press, 1999, p. 28.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, (editors Rolando E. Bonachea and Nelson P. Valdés), Che: Selected Works of Ernesto Guevara, Cambridge, MA: 1969, p. 350.

‡ Ernesto Che Guevara, "English Translation of Complete Text of Algiers Speech", Online at Sozialistische Klassiker, accessed January 42006. - ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, (editors Rolando E. Bonachea and Nelson P. Valdés), Che: Selected Works of Ernesto Guevara, Cambridge, MA: 1969, pp. 352-59.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, "English Translation of Complete Text of Algiers Speech", Online at Sozialistische Klassiker, accessed January 42006.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, "English Translation of Complete Text of his Message to the Tricontinental", or see Original Spanish text at Wikisource .

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, "Che Guevara's Farewell Letter", 1965. English translation of complete text: Che Guevara's Farewell Letter at Wikisource.

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life, New York: 1997, Grove Press, p. 628

- ^ Miná, Gianni. An Encounter with Fidel, Melbourne, 1991: Ocean Press, p 223.

- ^ Ahmed Ben Bella. "Che as I knew him". Online at Le Monde Diplomatique, accessed June 19, 2006. Heikal's account of Guevara's conversations with Nasser in February and March of 1965 lends further credence to this interpretation. See Heikal, Mohamed Hassanein. The Cairo Documents, pp 347-357.

- ^ Gálvez, William. Che in Africa: Che Guevara's Congo Diary, Melbourne, 1999: Ocean Press, p 62.

- ^ Gott, Richard. Cuba: A new history, Yale University Press 2004, p219

- ^ BBC News,"Profile: Laurent Kabila", 26 May 2001. Online at BBC News, accessed January 5 2006.

- ^ African History Blog, "Che Guevara's Exploits in the Congo", Che Guevara's Exploits in the Congo Online at African History, accessed January 52006.

- ^ Mad Mike Hoare Site, "Mad Mike". Online at Geocities.com, accessed January 52006.

- ^ Ireland's Own, "From Cuba to Congo, Dream to Disaster for Che Guevara". Onine at irelandsown.net, accessed January 112006.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, translated from the Spanish by Patrick Camiller, The African Dream, New York: Grove Publishers, 2000, p.1.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, "Che Guevara's Farewell Letter", 1965. English translation of complete text: Che Guevara's Farewell Letter at Wikisource.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, Apuntes Filosóficos, draft.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, Notas Económicas, draft.

- ^ Mittleman, James H. Underdevelopment and the Transition to Socialism - Mozambique and Tanzania, New York: 1981, Academic Press, p. 38

- ^ Major Donald R. Selvage - USMC, "Che Guevara in Bolivia", 1 April 1985. Online at GlobalSecurity.org, accessed January 52006.

- ^ Taibo, Paco Ignacio II. Ernesto Guevara, también conocido como el Che, Barcelona, 1999: Editorial Planeta, p 726.

- ^ U.S. Army, "Memorandum of Understanding Concerning the Activation, Organization and Training of the 2d Ranger Battalion – Bolivian Army (28 April 1967)". Online at http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB5/che14_1.htm, accessed June 192006.

- ^ Ryan, Henry Butterfield. The Fall of Che Guevara : A Story of Soldiers, Spies, and Diplomats, New York, 1998: Oxford University Press, p 82-102, inter alia.

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, "Excerpt from Pasajes de la guerra revolucionaria: Congo", Online at Cold War International History Project, accessed April 262006.

- ^ Castañeda, Jorge G. Che Guevara: Compañero, New York: 1998, Random House, pp 107-112; 131-132.

- ^ Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life. New York: Grove Press, 1997.

- ^ Richard Gott, "Bolivia on the Day of the Death of Che Guevara". Online at Mindfully.org, accessed February 26 2006

- ^ El Nuevo Cojo Ilustrado, "Galeria Che Guevara". Online, accessed April 27 2006

- ^ Rodriguez, Felix I. and John Weisman. Shadow Warrior/the CIA Hero of a Hundred Unknown Battles (Hardcover), New York: 1989, Publisher: Simon & Schuster

- ^ NewsMax, "Félix Rodríguez:Kerry No Foe of Castro". Online, accessed February 27 2006

- ^ Ernesto Che Guevara, "Diario (Bolivia)". Online, accessed February 262006.

- ^ Major Donald R. Selvage - USMC, "Che Guevara in Bolivia", 1 April 1985. Online at GlobalSecurity.org, accessed January 52006;

- ^ Alarcón Ramírez, Dariel dit "Benigno". Le Che en Bolivie, Paris: 1997, Éditions du Rocher

- ^

Carlos Puebla,"Carta al Che". Online, accessed February 262006.

Carlos Puebla,"Carta al Che". Online, accessed February 262006.

- ^

Carlos Puebla,"Hasta Siempre, Comandante". Online at BBC News, accessed February 262006.

Carlos Puebla,"Hasta Siempre, Comandante". Online at BBC News, accessed February 262006.

- ^ U.S. Department of State : Guevara's Death, The Meaning for Latin America p.6. October 12, 1967: Thomas Hughes, the Latin America specialist at the State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research providing an interpretive report for Secretary of State Dean Rusk

- ^ The Revolution of Che Guevara : French online magazine Bohème's assistant editor Sabrina Laurent. 2004.

- ^ BBC News, "Che Guevara photographer dies", 26 May 2001.Online at BBC News, accessed January 42006.

- ^

CBC Radio One, "Discussion about Che Guevara". Online, accessed February 262006.

CBC Radio One, "Discussion about Che Guevara". Online, accessed February 262006.

- ^ Abc.es, "El Che suplanta a Rudolf Hess" Online, accessed March 12 2006

- ^ Che-Lives, "Third Positionism - fascism in disguise". Online, accessed March 12 2006

- ^

Che Guevara, "Speech in Santiago de Cuba" (fragment), 29 November 1964. Online, accessed July 11 2006.

Che Guevara, "Speech in Santiago de Cuba" (fragment), 29 November 1964. Online, accessed July 11 2006.

- ^ CNN News, "Photo of Immigration Rally in Los Angeles", 25 March 2006.Online, accessed March 262006.

- ^ Socialism and Liberation, November 2005 [1], accessed September 22 2006

- ^ Michael Moynihan, "Neutering Sartre at Dagens Nyheter". Online at Stockholm Spectator. accessed February 26 2006

- ^ Samuel Farber, "The Resurrection of Che Guevara", Summer 1998. William Paterson University online, accessed June 18,2006.

- ^ Paquito D'Rivera, "Open letter to Carlos Santana by Paquito D'Rivera in Latin Beat Magazine", 25 March 2005. Find Articles Online, accessed June 18,2006

- ^ History News Network, "Che Guevara... The Dark Underside of the Romantic Hero". Online, accessed February 26 2006

- ^ Free Cuba Foundation, "Che Guevara's Dubious Legacy". Online, accessed February 26 2006

- ^ Paul Berman, "The Cult of Che", 24 September, 2004. Slate Online, accessed June 18, 2006.

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs Czech Republic, "International Committee for Democracy in Cuba". Online, accessed June 18, 2006.

- ^ Libertarian Community, "Ernesto "Che" Guevara, 1928-1967". Online, accessed February 26 2006

Content notes

^ Basque: Re origin of the surname Guevara — "Basque: Castilianized form of Basque Gebara, a habitational name from a place in the Basque province of Araba. The origin and meaning of the place name are uncertain; it is recorded in the form Gebala by the geographer Ptolemy in the 2nd century ad. This is a rare name in Spain." Dictionary of American Family Names, Patrick Hanks, ed., London: 2003, Oxford University Press. His mother, Celia de la Serna, was a direct descendant of the last Viceroy of Perú,General José de la Serna e Hinojosa, who was of documented Basque origin. [10] NB: For detailed genealogical information about Che Guevara, including his family tree, see Genealogy of Ernesto Guevara de la Serna.

^ Galway: The Lynch family was one of the famous 14 Tribes of Galway. The misconception exists that Ana María Isabel Lynch was born in Ireland, whereas she was actually born (1868) in San Francisco, California, USA where her father, Francisco Lynch, had traveled from Argentina during the Gold Rush years. Francisco had married a young Californian widow, Eloísa Ortiz, ca. 1860 and they had several other American-born children in addition to Ana Isabel. The man Ana Isabel would eventually marry, Roberto Guevara Castro, had also been born in California, USA of an Argentine father and a Californian mother who was the grand-daughter of the Spanish aristocrat Don Luís Peralta who had been given large land grants by the King of Spain; however, Ana Isabel and Roberto did not meet until both of their families had returned to Argentina. During Che's childhood, listening to his Grandmother Ana Isabel's tales of frontier life in California was one of his greatest delights.

^ Neruda: It is unclear whether he was familiar with the poems in which Neruda praised Fulgencio Batista, a principal future antagonist. A book of Neruda's poetry was found in Guevara's knapsack when he was captured in Bolivia.

^ Diploma: "12 de junio de 1953.- La Facultad de Ciencias Médicas de la Universidad de Buenos Aires le expide a Ernesto Guevara de la Serna el certificado de haber concluido la carrera de medicina. Esto se refleja en el legajo 1058, registro 1116, folio 153. Después participa en una fiesta de despedida que sus compañeros de la Clínica del doctor Salvador Pisani le hacen en la hacienda de la señora Amalia María Gómez Macías de Duhau." Che en el tiempo

^ Ibero-America: In a brief speech at the San Pablo leprosarium in Peru on the occasion of his 24th birthday, Guevara said: "Although we're too insignificant to be spokesmen for such a noble cause, we believe, and this journey has only served to confirm this belief, that the division of America into unstable and illusory nations is a complete fiction. We are one single mestizo race with remarkable ethnographical similarities, from Mexico down to the Magellan Straits. And so, in an attempt to break free from all narrow-minded provincialism, I propose a toast to Peru and to a United America." Source: Ernesto Che Guevara, Motorcycle Diaries, London: Verso Books, 1995, p.135.

^ Knapsack: "Quizás esa fue la primera vez que tuve planteado prácticamente ante mí el dilema de mi dedicación a la medicina o a mi deber de soldado revolucionario. Tenía delante de mí una mochila llena de medicamentos y una caja de balas, las dos eran mucho peso para transportarlas juntas; tomé la caja de balas, dejando la mochila ..." (English: "Perhaps this was the first time I was confronted with the real-life dilemma of having to choose between my devotion to medicine and my duty as a revolutionary soldier. Lying at my feet were a knapsack full of medicine and a box of ammunition. They were too heavy for me to carry both of them. I grabbed the box of ammunition, leaving the medicine behind ...".) First published in an article in Verde Olivo, La Habana, Cuba, February 26 1961. Subsequently published in the book, Guevara, Ernesto Che. Pasajes de la Guerra Revolucionaria, La Habana, Cuba: 1963, Ediciones Unión.

^ Children: With Hilda Gadea (married 8 August 1955; divorced 22 May 1959) : one daughter, Hilda Beatriz Guevara Gadea, born 15 February 1956 in Mexico City; died 21 Aug 1995 in Havana, Cuba

With Aleida March (married 2 June 1959):

- Aleida Guevara March, born 24 November 1960 in Havana, Cuba

- Camilo Guevara March, born 20 May 1962 in Havana, Cuba

- Celia Guevara March, born 14 June 1963 in Havana, Cuba

- Ernesto Guevara March, born 24 February 1965 in Havana, Cuba

With Lilia Rosa López (extramarital): one son, Omar Pérez, born 19 March 1964 in Havana, Cuba

^ INRA: appointed Director of the Industrialization Department of the National Institute for Agrarian Reform on October 7 1959

^ BNC: appointed President of the National Bank of Cuba on November 26 1959

^ Signature: "If my way of signing is not typical of bank presidents ... this does not signify, by any means, that I am minimizing the importance of the document — but that the revolutionary process is not yet over and, besides, that we must change our scale of values." — Ernesto Guevara, quoted by Aleksandr Alexeiev in "Cuba después del triunfo de la revolución" ("Cuba after the triumph of the revolution"), Revista de América Latina (Moscow), no. 10, October 1984, p. 57 (referenced in Castañeda, op. cit, p. 169).

^ MININD: appointed Minister of Industries on February 23 1961

^ Algeria: In September 1962, Algeria asked Cuba for assistance when Morocco declared war on it over their dispute concerning the territory formerly known as the Spanish Sahara. Cuba responded by sending a contingent of Cuban officers and troops totalling 686 men and some 60 tanks to support the Algerian forces. Shortly after news of the landing of the Cuban troops at Oran leaked to the press, King Hassan II of Morocco agreed to sign a cease-fire with President Ben Bella of Algeria. The Cuban expeditionary force remained in Algeria for six months, during which time they set up the military equipment they had brought and trained their Algerian counterparts in its use. Guevara played a major role in organizing and executing the Cuban deployment. Sources: Piero Gliejeses, "Cuba's First Venture in Africa: Algeria, 1961–1965", Journal of Latin American Studies, no. 28, London: Cambridge University Press, Spring 1996, p. 188 and Castañeda, pp. 244-245.

^ Kabila: In May 1997, Laurent-Désiré Kabila overthrew the government of Mobutu Sese Seko and became President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He held that position until his assassination on January 16, 2001 and was succeeded in the presidency by his son, Joseph Kabila.

^ Camp: The purchase of the acreage in the Ñancahuazú region was in direct contravention of Guevara's directive that the land for the camp should be purchased in the Alto Beni region. When presented with the fait accompli that the Bolivian Communists had acquired land in the Ñancahuazú region instead, he at first complained but eventually decided to utilize it in order not to lose time while waiting for them to purchase a parcel in the Alto Beni.

^ USMilitary: "U.S. military personnel in Bolivia never exceeded 53 advisors, including a sixteen-man Mobile Training Team (MTT) from the 8th Special Forces Group based at Fort Gulick, Panama Canal Zone. Commanded by Major Ralph ('Pappy') Shelton, the MTT set up a training camp near Santa Cruz. The advisors arrived on April 29 and instituted a 19 week counter-insurgency training program for the Bolivian 2nd Ranger Battalion. The intensive course included training in weapons, individual combat, squad and platoon tactics, patrolling, and counter-insurgency. The Bolivians responded well to the training and quickly developed into a spirited, confident, and effective counter guerrilla unit." — Che Guevara in Bolivia by Major Donald R. Selvage.

^ Message: For example, on August 31 1967 Che wrote in his diary "Hay mensaje de Manila pero no se pudo copiar.", i.e. "There is a (coded radio) message from Manila ('Manila' being the code name for Havana) but we couldn't copy it." The content of this message has not been revealed, but it may have been of critical importance since by then Castro and the other Cubans who were directing the guerrillas' support network from Havana had to be aware of their dire straits.

^ Barrientos: Although Barrientos never revealed his motives for ordering the summary execution of Guevara, some of his associates have suggested that he took this decision primarily in order to avoid the spectacle of a "show trial" that would have brought unwelcome international attention to Bolivia, and that he was also concerned that, had Guevara been sentenced to a lengthy term in a Bolivian prison, he might have escaped or eventually been released (as in Fidel Castro's case), and subsequently resumed his guerrilla activities.

^ Amputation: Castañeda, Jorge G., Che Guevara: Compañero, New York: 1998, Random House, pp. xiii - xiv; pp. 401-402. Guevara's amputated hands, preserved in formaldehyde, turned up in the possession of Fidel Castro a few months later. Castro reportedly wanted to put them on public display but was dissuaded from doing so by the vehement protests of members of Guevara's family.

^ Mausoleum: On December 30 1998 the remains of ten more guerrillas who had fought alongside Guevara in Bolivia and whose secret burial sites there had been recently discovered by Cuban forensic investigators were placed inside the "Che Guevara Mausoleum" in Santa Clara. Also inside the mausoleum is the original letter[1] Guevara wrote to Castro in which he stated that he was leaving Cuba to fight abroad for the cause of the revolution, resigned all his party, military and governmental posts, and renounced his Cuban citizenship.

References

Printed matter

- Alarcón Ramírez, Dariel ("Benigno"). Memorias de un Soldado Cubano: Vida y Muerte de la Revolución. Barcelona: Tusquets Editores S.A., 2002. ISBN 8483100142

- Alarcón Ramírez, Dariel dit "Benigno". Le Che en Bolivie. Éditions du Rocher, 1997. ISBN 2-268-02437-7

- Anderson, Jon Lee. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life. New York: Grove Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8021-1600-0

- Bravo, Marcos. La Otra Cara Del Che. Bogota, Colombia: Editorial Solar, 2005. “I’d like to confess, papá, at that moment I discovered that I really like killing.” Guevara writing to his father.

- Castañeda, Jorge G. Che Guevara: Compañero. New York: Random House, 1998. ISBN 0-679-75940-9

- Castro, Fidel (editors Bonachea, Rolando E. and Nelson P. Valdés). Revolutionary Struggle. 1947-1958. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: MIT Press, 1972. ISBN 0-262-02065-3

- Feldman, Allen 2003. Political Terror and the Technologies of Memory: Excuse, Sacrifice, Commodification, and Actuarial Moralities. Radical History Review 85, 58-73.

- Escobar, Froilán and Félix Guerra. Che: Sierra adentro (Che: Deep in the Sierra). Havana: Editora Política, 1988.

- Fuentes, Norberto. La Autobiografía De Fidel Castro ("The Autobiography of Fidel Castro"). Mexico D.F: Editorial Planeta, 2004. ISBN 84-233-3604-2, ISBN 970-749-001-2

- Gálvez, William. Che in Africa: Che Guevara's Congo Diary. Melbourne: Ocean Press, 1999. ISBN 1-876175-08-7

- George, Edward. The Cuban Intervention In Angola, 1965-1991: From Che Guevara To Cuito Cuanavale. London & Portland, Oregon: Frank Cass Publishers, 2005. ISBN 0-415-35015-8

- Gliejeses, Piero. Cuba's First Venture in Africa: Algeria, 1961–1965, Journal of Latin American Studies, no. 28, London: Cambridge University Press, Spring 1996.

- Guevara, Ernesto "Che". Pasajes de la guerra revolucionaria

- Guevara, Ernesto "Che" (editors Bonachea, Rolando E. and Nelson P. Valdés). Che: Selected Works of Ernesto Guevara, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1969. ISBN 0-262-52016-8

- Guevara, Ernesto "Che" (editor Waters, Mary Alice). Episodes of the Cuban Revolutionary War 1956-1958. New York: Pathfinder, 1996. ISBN 0-87348-824-5 (See reference to "El Viscaíno" on page 186).

- Guevara, Ernesto "Che", translated from the Spanish by Patrick Camiller. The African Dream, New York: Grove Publishers, 2000. ISBN 0-8021-3834-9

- Guevara Lynch, Ernesto. Aquí va un soldado de América. Barcelona: Plaza y Janés Editores, S.A., 2000. ISBN 84-01-01327-5

- Heikal, Mohamed Hassanein. The Cairo Documents. New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1973. ISBN 0-385-06447-0

- Holland, Max. Private Sources of U.S. Foreign Policy William Pawley and the 1954 Coup d'État in Guatemala in Journal of Cold War Studies, Volume 7, Number 4, Fall 2005, pp. 36-73.

- James, Daniel. Che Guevara. New York: Cooper Square Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8154-1144-8

- Matos, Huber. Como llegó la Noche ("As night arrived"). Barcelona: Tusquet Editores, SA, 2002. ISBN 84-8310-944-1

- Miná, Gianni. An Encounter with Fidel. Melbourne: Ocean Press, 1991. ISBN 1-875284-22-2

- Morán Arce, Lucas. La revolución cubana, 1953-1959: Una versión rebelde ("The Cuban Revolution, 1953-1959: a rebel version"). Ponce, Puerto Rico: Imprenta Universitaria, Universidad Católica, 1980. ISBN B0000EDAW9.

- Peña, Emilio Herasme. La Expedición Armada de junio de 1959, Listín Diario, (Dominican Republic), 14 June 2004.

- Peredo-Leigue, Guido "Inti". Mi campaña junto al Che, México: Ed. Siglo XXI, 1979. File:Adobepdfreader7 icon.png PDF version.

- Rodriguez, Félix I. and John Weisman. Shadow Warrior/the CIA Hero of a Hundred Unknown Battles. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1989. ISBN 0-671-66721-1

- Rojo del Río, Manuel. La Historia Cambió En La Sierra ("History changed in the Sierra"). 2a Ed. Aumentada (Augmented second edition). San José, Costa Rica: Editorial Texto, 1981.

- Ros, Enrique 2003. Fidel Castro y El Gatillo Alegre: Sus Años Universitarios (Colección Cuba y Sus Jueces). Miami: Ediciones Universal. ISBN 1-59388-006-5

- Ryan, Henry Butterfield. The Fall of Che Guevara : A Story of Soldiers, Spies, and Diplomats. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-511879-0

- Taibo, Paco Ignacio II. Ernesto Guevara, también conocido como el Che. Barcelona: Editorial Planeta, 1999. ISBN 84-08-02280-6

- Vargas Llosa, Álvaro. The Killing Machine: Che Guevara, from Communist Firebrand to Capitalist Brand in The New Republic

- Villegas, Harry "Pombo". Pombo : un hombre de la guerrilla del Che : diario y testimonio inéditos, 1966-1968. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Colihue S.R.L., 1996. ISBN 950-581-667-7

Websites

- "ABC.es". Retrieved June 28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "African History". Retrieved June 28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "BBC News". Retrieved June 19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "CBC Radio One". Retrieved June 20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Che-Lives (RevolutionaryLeft.com)". Retrieved February 26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "chessgames.com". Retrieved June 27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "CIA Biographic Register on Che Guevara". Retrieved July 12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "CNC TV". Retrieved February 26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "CNN News". Retrieved March 26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Cuba SI". Retrieved June 27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Cuban Information Archives(cuban-exile.com)". Retrieved 27 June.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Cuban Aviation". Retrieved February 26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "El Nuevo Cojo Ilustrado". Retrieved June 28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Ernesto Che Guevara - Ajedrez". Retrieved June 29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Find Articles". Retrieved June 18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Florida International University". Retrieved June 28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "FrontPage Magazine". Retrieved June 27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "GlobalSecurity.org". Retrieved June 27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Granma Internacional Digital". Retrieved June 26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Guaracabuya". Retrieved February 26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "History News Network". Retrieved June 27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Ireland's OWN: History". Retrieved June 28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Latino Studies Resources". Retrieved June 27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Le Monde Diplomatique". Retrieved June 19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "libertarian community and organising resource". Retrieved June 28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Listín Diario". Retrieved January 4.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "MadMikeHoare.com". Retrieved June 27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Marxists Internet Archive". Retrieved June 28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Mindfully.org". Retrieved June 28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Ministry of Foreign Affairs Czech Republic". Retrieved June 18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "National Security Archive at George Washington University". Retrieved June 19.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "NewsMax". Retrieved June 28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Periódico 26, Las Tunas, Cuba". Retrieved June 27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Radio Bayamo". Retrieved February 26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Radio Cadena Agramonte". Retrieved June 27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Sitio del Gobierno de la República de Cuba". Retrieved June 27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Slate". Retrieved June 18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - "Sozialistische Klassiker". Retrieved June 26.