History of Somalia

Somalia (Somali: Soomaaliya) is a coastal nation in East Africa, widely known as Horn of Africa. Continentally, it is surrounded by Ethiopia and Djibouti on the north and mid-west, and Kenya on its south-west. The Gulf of Aden is located on its far east.

This article describes its overall history. See Somalia for details of the country as it is today.

Prehistoric Era

The great masterpiece that the ancient civilization produced is thought to be the most significant Neolithic cave paintings in the Horn of Africa and the African continent in general - known as The Laas Geel rock paintings. These cave paintings are located in a site outside the capital Hargeisa. These paintings were untouched and intact for nearly 10,000 years until it was discovered recently. The paintings show the indigenous people worshiping cattle. There are also paintings of giraffes, domesticated canines and wild antelopes. The paintings show the cows wearing ceremonial robes while next to them are the natives performing rituals in front of the cattle. The caves were discovered by a French archaeological team during November and December 2002. Hence, the Laas Geel cave paintings have become a major tourist attraction and a national treasure.

The Land of Punt

Somalia together with Ethiopia,Eritrea,Djibouti (also known as the Horn of Africa.) were known to the Ancient Egyptians as the Land of Punt The earliest definite record of contact between Ancient Egypt and Punt comes from an entry on the Palermo stone during the reign of Sahura of the Fifth Dynasty around 2250 BC it says in one year 80,000 units of myrrh and frankincense was brought to Egypt from Punt as well as other quantities of goods that were highly valued in Ancient Egypt. between the Thirteenth and Seventeenth Dynasties, the contact between Egypt and Punt was broken. This was due to the fact that Egypt was invaded by the Hyksos The fifth ruler in the Eighteen Dynasty of Egyptian Pharaohs was Queen Hatshepsut, daughter of Tutmose III. She became Queen in the year 1493 B.C. and made a landmark expedition to the land of Punt wich is recorded on the walls of the Deir ci-Bahari temple located in Alexandria. Her eight ships sailed to Puntland and came back with cargoes of fine woods, ebony, myrrh, cinnamon and incense trees to plant in the temple garden.

Ancient Trading Ports

G.W.B. Huntingford has argued in his translation of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, written in the first century BC, that the "Lesser and Greater Bluffs", the "Lesser and Greater Strands", and the "Seven Courses" of Azania all should be identified with the Somali coastline from Hafun south to Siyu Channel. This indicates that parts of Somalia were familiar to Roman and Indian traders by this time.

the inhabitants were referred to as the Black Berbers. For five centuries (second to seventh century AD) parts of Somalia came under the rule of the Ethiopian/Eritrean Kingdom of Aksum.

In the 7th Century AD, Arab traders began to trade with the locals who according to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea already were active in commerce with foreign nations, the local Cushitic people, founded the sultanate of Adal, the main port of which was Zeila (now Saylac).

The newly established Sultanate put the Somalis in contact with Arab traders travelling along the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. In the ensuing centuries, the Somalis converted to Islam.To the west there was a lot of trading done with the people living with the Oromos, the Afars and the people living in modern-day Eritrea.

Zheng He & Ibn Battuta

Between the 13th and 14th centuries Somalia was visited by two famous muslim explorers Ibn Battuta and Zheng He. Ibn Battuta in 1331 visited Mogadishu, which he described as a town of enormous size. and Its merchants possessed vast resources; they owned large numbers of camels, of which they slaughtered hundreds every day for food, and also had large quantities of sheep.The woven fabrics that were manufactured there he claimed were unequalled and were exported as far as Egypt and elswere. Zheng He on his fifth voyage (1417-19) visited several city states on the Somali coast including Mogadishu

The Rise of Adal & the Ethiopian Empire

Muslim Somalia enjoyed friendly relations with neighboring Christian Ethiopia for centuries. Despite jihad raging everywhere else in the Muslim world, Muhammad had issued a hadith proscribing Muslims from attacking Ethiopia (so long as Ethiopia was not the aggressor), as it had sheltered some of Islam's first converts from persecution in modern-day Saudi Arabia. Parts of northwestern Somalia (modern northwestern Somaliland) came under the rule of the Solomonic Ethiopian Kingdom in medieval times, especially during the reign of Amda Seyon I (r. 1314-1344). In 1403 or 1415 (under Emperor Dawit I or Emperor Yeshaq I, respectively) measures were taken against the medieval Muslim kingdom of Adal (located in eastern Ethiopia and western Somaliland, centered around Harar and comprised of both Somalis and Afars), a tributary kingdom that revolted and whose raids were disrupting rule in adjacent areas. His campaign was eventually successful, but took much longer than other campaigns at the time due to the tendency of Adal warriors to disappear into the countryside after fighting. In 1403 (or 1415), the Emperor eventually captured King Sa'ad ad-Din II in Zeila and had him executed. The Walashma Chronicle, however, records the date as 1415, which would make the Ethiopian victor Emperor Yeshaq I. After the war, the reigning king had his minstrels compose a song praising his victory, which contains the first written record of the word "Somali".

The area remained under Ethiopian control for another century or so. However, starting around 1527 under the charismatic leadership of Imam Ahmed Gragn (Gurey in Somali, Gragn in Amharic, both meaning "left-handed), Adal revolted and invaded Ethiopia. Regrouped Muslim armies with Ottoman support and arms marched into Ethiopia employing scorched earth tactics and slaughtered any Ethiopian that refused to convert from Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity to Islam.[1] Moreover, hundreds of churches were destroyed during the invasion, and an estimated 80% of the manuscripts in the country were destroyed in the process. Adal's use of firearms, still only rarely used in Ethiopia, allowed the conquest of well over half of Ethiopia, reaching as far north as Tigray. The complete conquest of Ethiopia was averted by the timely arrival of a Portuguese expedition led by Cristovão da Gama, son of the famed navigator Vasco da Gama. The Portuguese had been in the area earlier in early 16th centuries (in search of the legendary priest-king Prester John), and although a diplomatic mission from Portugal, led by Rodrigo de Lima, had failed to improve relations between the countries, they responded to the Ethiopian pleas for help and sent a military expedition to their fellow Christians. a Portuguese fleet under the command of Estêvão da Gama was sent from India and arrived at Massawa in February 1541. Here he received an ambassador from the Emperor beseeching him to send help against the Muslims, and in July following a force of 400 musketeers, under the command of Christovão da Gama, younger brother of the admiral, marched into the interior, and being joined by Ethiopian troops they were at first successful against the muslims but they were subsequently defeated at the Battle of Wofla (28 August 1542), and their commander captured and executed. On February 21, 1543, however,a joint Portuguese-Ethiopian force defeated the Muslim army at the Battle of Wayna Daga, in which Ahmed Gragn was killed and the war won.

Ahmed Gragn's widow married Nur ibn Mujahid in return for his promise to avenge Ahmed's death, who succeeded Ahmed Gragn, and continued hostilities against his northern adversaries until he killed the Ethiopian Emperor in his second invasion of Ethiopia, Emir Nur died in 1567; the Ethiopians sacked Zeila in 1660.[citation needed] The Portuguese, meanwhile, tried to conquer Mogadishu but according to Duarta Barbosa never succeeded in taking it. The sultanate of Adal disintegrated into small independent states, many of which were ruled by Somali chiefs. Zeila became a dependency of Yemen, and was then incorporated into the Ottoman Empire.

Ajuuraan Dynasty

On the other side of East Africa in the 14th century the Ajuuran dynasty formed a centralized state in the lower Shabeelle valley, ruling over a territory that stretched as far inland as modern Qalafo and towards the coast almost to Mogadishu. Said S. Samatar, writing with David Laitin, notes that the Ajuuran sultanate "represents one of the rare occasions in Somali history when a pastoral state achieved large-scale centralization", and notes that it grew larger and more powerful than coastal city-states of Mogadishu, Merka and Baraawe combined.[2]

Hobyo the ancient port of Somalia was the commercial centre of the Ajuuraan Sultanate,all the commercial goods grown or harvested along the Shabelle river were brought to Hobyo to trade, as Hobyo remained the active mercantile pitstop of ancient times. The Ajuuraan rulers collected their tribute from the town in the form of sorghum (durra), making the port of Hobyo incredibly profitable for the Ajuuraan sultans.

trade between Hobyo and the Banaadir coast flourished for some time. So vital was Hobyo to the prosperity of the Ajuuraan Sultanate that when a local sheikhs successfully revolted against the Ajuuraan Sultan and established an independent Imamate of the Hiraab , the power of the Ajuuraan sultans crumbled within a century

Due to Portuguese predations, internal discord, and encroaching nomads from the north, the Ajuuran sultanate disintegrated at the end of the 17th century. According to Said Samatar, almost a full century passed before a successor state emerged: the Geledi Sultanate, which was based in the town of Afgooye and ruled over the lower Shabeelle region. Meanwhile, the Sultanate of Oman of south Arabia ousted the Portuguese from the Benaadir coast, and ruled the Benaadir coast with what Samatar describes as a "light hand" until the European Scramble for Africa in the 1880s. "As long as the Somali cities paid their yearly tribute (which was by no means extortionate), flew the Omani flag, and accepted Omani overlordship, the Omanis allowed the Somalis to run their internal affairs. The role of the Omani governors in Mogadishu, Merca, and Baraawe was largely a ceremonial one. However, when Omani authority was challenged, the Omanis could be severe."[3]

In the 17th century, Somalia fell under the sway of the rapidly expanding Ottoman Empire, who exercised control through hand picked local Somali governors. In 1728 the Ottomans evicted the last Portuguese occupation and claimed sovereignty over the whole Horn of Africa. However, their actual exercise of control was fairly modest, as they demanded only a token annual tribute and appointed an Ottoman judge to act as a kind of Supreme Court for interpretations of Islamic law. By the 1850s Ottoman power was in decline.

Farther east on the Bari coast,two kingdoms emerged that would play a significant political role on the Somali Peninsula prior to colonization. These were the Majeerteen Sultanate of Boqor(king) Osman Mahamuud, and that of his kinsman Sultan Yuusuf Ali Keenadiid of Hobyo (Obbia). The Majeerteen Sultanate originated in the mid eighteenth century, but only came into its own in the nineteenth century with the reign of the resourceful Boqor Osman. Boqor Osman Mahamuud's kingdom benefited from British subsidies (for protecting the British naval crews that were shipwrecked periodically on the Somali coast) and from a liberal trade policy that facilitated a flourishing commerce in livestock, ostrich feathers, and gum arabic. While acknowledging a vague vassalage to the British, the Sultan kept his kingdom free until well after 1900's.

Boqor Ismaan Mahamuud's sultanate was nearly destroyed in the middle of the nineteenth century by a power struggle between him and his young, ambitious cousin, Keenadiid. Nearly five years of destructive civil war passed before Boqor Ismaan Mahamuud managed to stave off the challenge of the young upstart, who was finally driven into exile in Arabia. A decade later, in the 1870s, Keenadiid returned from Arabia with a score of Hadhrami musketeers and a band of devoted lieutenants. With their help, he carved out the small kingdom of Hobyo after conquering the local clans.

Scramble for Africa

Starting in 1875 the age of Imperialism in Europe transformed Somalia. Britain, France, and Italy all made territorial claims on the peninsula. Britain already controlled the port city of Aden in Yemen, just across the Red Sea, and wanted to control its counterpart, Berbera, on the Somali side. The Red Sea was a crucial shipping lane to British colonies in India, and they wanted to secure these "gatekeeper" ports at all costs.

The French were interested in coal deposits further inland and wanted to disrupt British ambitions to construct a north-south transcontinental railroad along Africa's east coast, by blocking an important section.

Italy had just recently been reunited and was an inexperienced colonialist. They were happy to grab up any African land they didn't have to fight other Europeans for. They took control of the southern part of Somalia, which would become the largest European claim in the country, but the least strategically significant.

In 1884 Egypt, which had declared independence from the waning Ottoman Empire, had ambitions of restoring its ancient power, and set its sights on East Africa. However, the Sudanese resisted Egypt's advance and the Mahdist revolution of 1885 ejected the Egyptians from Sudan and shattered Egypt's hope of a neo-Egyptian empire. The few advance troops that had made it to Somalia had to be rescued by the British and escorted back to their own side of the fence.

Thereafter, the biggest threat to European colonial ambitions in Somalia came from Ethiopian Emperor Menelik II who had successfully avoided having his own country occupied, and was planning to invade Somalia again. By 1900 he had seized the Ogaden region in western Somalia,wich was reconquered by the Mullah during the Dervish colonial resistance war[3] and then ceded to Ethiopia by Britain in 1945. Even today, long after all the Europeans had given up on their relatively valuable colonial possessions, Ogaden, the most barren of Somali provinces, is still frequently fought over by the two bordering nations.

Dervish Resistance

Somali resistance to foreign powers began in 1899 under the leadership of religious scholar Sayyid Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, Ogaden sub-lineage of the Darod tribe and his mother was Dulbahante sub-lineage of the Darod tribe. Their primary targets were their traditional enemies the Ethiopians, and the British who controlled the most lucrative ports and were squeezing tax money from farmers who had to use the ports to ship their livestock to customers in the Middle East and India. Hasan was a brilliant orator and poet with a very strong following of Islamic fundamentalist dervishes all of which came from the Dulbahante tribe, these relentless and well organized warriors were Hasan's maternal relatives. They waged a bloody guerrilla war. This war lasted over two decades until the British Royal Air Force, having honed their skills in World War I, led a devastating bombing campaign against dervish strongholds in 1920, which caused Hasan to flee (he died of pneumonia soon after). The dervish struggle was one of the longest and bloodiest anti-Imperial resistance wars in sub-Saharan Africa, and cost the lives of nearly a third of northern Somalia's population: the Dulbahante lost half of their population during this era and there were heavy casualties on the Ethiopian and British sides as well. This was mainly due to the Dulbahante's refusal to sign the Protectorate Treaty and submit to British colonial rule. The Isaaq, the Issa, the Warsangali as well as the Gadabuursi signed the treaty with the British without any loss of life. The Dulbahante viewed themselves as the sole protector of greater Somalia, and resented the signatory tribes. After the long Anglo-dervish wars the British colonial leaders did not trust the Somalis; therefore, immediately after the Isaaq's, the Issa's, the Warsangali's, and the Gadabuursi signed the treaty, they invoked article 7 of the treaty, sub-section 3(a)(j)(k) of which allowed the British Colonial Authority to enforce segregation rule and a head tax. It also subjected the children of the tribes that signed the treaty to CCTP (Children under Colonial Power under sub-section 3k). CCTP dictated separating a percentage of the children from their mothers for special education, although the actual intent was to instill fear into the treaty members to enforce law and order. This caused some of the aformentioned tribal leaders to regret signing the treaty and wish they had resisted as the Dulbahante's had done.

While the British were bogged down by Mohammed Abdullah Hassan (known to the British as 'The Mad Mullah'), the French made little use of their Somalian holdings, content that as long as the British were stymied, their job was done. This attitude may have contributed to why they were more or less left alone by the Dervishes. The Italians, though, were intent on larger projects and established an actual colony to which a significant number of Italian civilians migrated and invested in major agricultural development. By this time Mussolini was in power in Italy. He wanted to improve the world's respect for Italy by expert economic management of Italy's new colonies, upstaging the British and their various embarrassing problems with the Somalis.

Due to the constant fighting the British were afraid to invest in any expensive infrastructure projects that might easily be destroyed by guerillas. As a result, when the country was eventually reunited in the 1960s, the north, which had been under British control, lagged far behind the south in terms of economic development, and came to be dominated by the South. The bitterness from this state of affairs would be one of the sparks for the future civil war.

Italian Campaigns

The dawn of fascism in the early 1920s heralded a change of strategy for Italy as the north-eastern sultanates were soon to be forced within the boundaries of La Grande Somalia according to the plan of fascist Italy. With the arrival of Governor Cesare Maria De Vecchi on 15 December 1923 things began to change for that part of Somaliland. Italy had access to these parts under the successive protection treaties, but not direct rule. The fascist government had direct rule only over the Benaadir territory.

Given the defeat of the Dervish movement in the early 1920s and the rise of fascism in Europe, on 10 July 1925 Benito Mussolini gave the green light to De Vecchi to start the takeover of the north-eastern sultanates. Everything was to be changed and the treaties abrogated.

The real principles of colonialism meant possession and domination of the people, and the protection of the country from other greedy powers. Italy's interpretation of the treaties of protection with the north-eastern sultanates was comparable to her view of the Treaty of Uccialli with Abyssinia, and meant absolute control of the whole territory. Never mind that the subsequent tension between Abyssinia and Italy had culminated in 1896 in the battle of Adwa in which the Italians were overwhelmed and defeated. The Italians had not learned their lesson, they were committing the same historical mistake.

Governor De Vecchi's first plan was to disarm the sultanates. But before the plan could be carried out there should be sufficient Italian troops in both sultanates. To make the enforcement of his plan more viable, he began to reconstitute the old Somali police corps, the Corpo Zaptié, as a colonial force.

In preparation for the plan of invasion of the sultanates, the Alula Commissioner, E. Coronaro received orders in April 1924 to carry out a reconnaissance on the territories targeted for invasion. In spite of the forty year Italian relationship with the sultanates, Italy did not have adequate knowledge of the geography. During this time, the Stefanini-Puccioni geological survey was scheduled to take place, so it was a good opportunity for the expedition of Coronaro to join with this.

Coronaro's survey concluded that the Majeerteen Sultanate depended on sea traffic, therefore, if this were blocked any resistance which could be mounted came after the invasion of the sultanate would be minimal. As the first stage of the invasion plan Governor De Vecchi ordered the two Sultanates to disarm. The reaction of both sultanates was to object, as they felt the policy was in breach of the protectorate agreements. The pressure engendered by the new development forced the two rival sultanates to settle their differences over Nugaal possession, and form a united front against their common enemy.

The Sultanate of Hobyo was different from that of Majeerteen in terms of its geography and the pattern of the territory. It was founded by Yusuf Ali in the middle of the nineteenth century in central Somaliland. The jurisdiction of Hobyo stretched from El-Dheere through to Dusa-Mareeb in the south-west, from Galladi to Galkayo in the west, from Jerriiban to Garaad in the north-east, and the Indian Ocean in the east.

By 1st October, De Vecchi's plan was to go into action. The operation to invade Hobyo started in October 1925. Columns of the new Zaptié began to move towards the sultanate. Hobyo, El-Buur, Galkayo, and the territory between were completely overrun within a month. Hobyo was transformed from a sultanate into an administrative region. Sultan Yusuf Ali surrendered. Nevertheless, soon suspicions were aroused as Trivulzio, the Hobyo commissioner, reported movement of armed men towards the borders of the sultanate before the takeover and after. Before the Italians could concentrate on the Majeerteen, they were diverted by new setbacks. On 9 November, the Italian fear was realised when a mutiny, led by one of the military chiefs of Sultan Ali Yusuf, Omar Samatar, recaptured El-Buur. Soon the rebellion expanded to the local population. The region went into revolt as El-Dheere also came under the control of Omar Samatar. The Italian forces tried to recapture El-Buur but they were repulsed. On 15 November the Italians retreated to Bud Bud and on the way they were ambushed and suffered heavy casualties.

While a third attempt was in the last stages of preparation, the operation commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Splendorelli, was ambushed between Bud Bud and Buula Barde. He and some of his staff were killed. As a consequence of the death of the commander of the operations and the effect of two failed operations intended to overcome the El-Buur mutiny, the spirit of Italian troops began to wane. The Governor took the situation seriously, and to prevent any more failure he requested two battalions from Eritrea to reinforce his troops, and assumed lead of the operations. Meanwhile, the rebellion was gaining sympathy across the country, and as far a field as Western Somaliland.

The fascist government was surprised by the setback in Hobyo. The whole policy of conquest was collapsing under its nose. The El-Buur episode drastically changed the strategy of Italy as it revived memories of the Adwa fiasco when Italy had been defeated by Abyssinia. Furthermore, in the Colonial Ministry in Rome, senior officials distrusted the Governor's ability to deal with the matter. Rome instructed De Vecchi that he was to receive the reinforcement from Eritrea, but that the commander of the two battalions was to temporarily assume the military command of the operations and De Vecchi was to stay in Mogadishu and confine himself to other colonial matters. In the case of any military development, the military commander was to report directly to the Chief of Staff in Rome.

While the situation remained perplexed, De Vecchi moved the deposed sultan to Muqdisho. Fascist Italy was poised to re-conquer the sultanate by whatever means. To manoeuvre the situation within Hobyo, they even contemplated the idea of reinstating Ali Yusuf. However, the idea was dropped after they became pessimistic about the results.

To undermine the resistance, however, and before the Eritrean reinforcement could arrive, De Vecchi began to instil distrust among the local people by buying the loyalty of some of them. In fact, these tactics had better results than had the military campaign, and the resistance began gradually to wear down. Given the anarchy which would follow, the new policy was a success.

On the military front, on 26 December 1925 Italian troops finally overran El-Buur, and the forces of Omar Samatar were compelled to retreat to Western Somaliland.

By neutralising Hobyo, the fascists could concentrate on the Majeerteen. In early October 1924, E. Coronaro, the new Alula commissioner, presented Boqor(king) Osman with an ultimatum to disarm and surrender. Meanwhile, Italian troops began to pour into the sultanate in anticipation of this operation. While landing at Haafuun and Alula, the sultanate's troops opened fire on them. Fierce fighting ensued and to avoid escalating the conflict and to press the fascist government to revoke their policy, Boqor Osman tried to open a dialogue. However, he failed, and again fighting broke out between the two parties. Following this disturbance, on 7 October the Governor instructed Coronaro to order the Sultan to surrender; to intimidate the people he ordered the seizure of all merchant boats in the Alula area. At Haafuun, Arimondi bombarded and destroyed all the boats in the area.

On 13 October Coronaro was to meet Boqor Osman at Baargaal to press for his surrender. Under siege already, Boqor Osman was playing for time. However, on 23 October Boqor Osman sent an angry response to the Governor defying his order. Following this a full scale attack was ordered in November. Baargaal was bombarded and razed to the ground. This region was ethnically compact, and was out of range of direct action by the fascist government of Muqdisho. The attempt of the colonizers to suppress the region erupted into explosive confrontation. The Italians were meeting fierce resistance on many fronts. In December 1925, led by the charismatic leader Hersi Boqor, son of Boqor Osman, the sultanate forces drove the Italians out of Hurdia and Haafuun, two strategic coastal towns on the Indian Ocean. Another contingent attacked and destroyed an Italian communications centre at Cape Guardafui, on the tip of the Horn. In retaliation Bernica and other warships were called on to bombard all main coastal towns of the Majeerteen. After a violent confrontation Italian forces captured Ayl (Eil), which until then had remained in the hands of Hersi Boqor. In response to the unyielding situation, Italy called for reinforcements from their other colonies, notably, Eritrea. With their arrival at the closing of 1926, the Italians began to move into the interior where they had not been able to venture since their first seizure of the coastal towns. Their attempt to capture Dharoor Valley was resisted, and ended in failure.

De Vecchi had to reassess his plans as he was being humiliated on many fronts. After one year of exerting full force he could not yet manage to gain a result over the sultanate. In spite of the fact that the Italian navy sealed the sultanate's main coastal entrance, they could not succeed in stopping them from receiving arms and ammunition through it. It was only early 1927 when they finally succeeded in shutting the northern coast of the sultanate, thus cutting arms and ammunition supplies for the Majeerteen. By this time, the balance had tilted to the Italian's side, and in January 1927 they began to attack with a massive force, capturing Iskushuban, at the heart of the Majeerteen. Hersi Boqor unsuccessfully attacked and challenged the Italians at Iskushuban. To demoralise the resistance, ships were ordered to raze and bombard the sultanate's coastal towns and villages. In the interior the Italian troops confiscated livestock. By the end of the 1927 the Italians had nearly taken control of the sultanate. Defeated and Hersi Boqor and his top staff were forced to retreat to Ethiopia in order to rebuild the forces. However, they had an epidemic of cholera which frustrated all attempts to recover his force.

With the elimination of the north-eastern sultanates and the breaking of the Benaadir resistance, from this period henceforth, Italian Somaliland was to become a reality.

By 1935, the British were ready to cut their losses in Somalia. The dervishes refused to accept any negotiations. Even after they had been soundly defeated in 1920, sporadic violence continued for the entire duration of British occupation. To make matters worse, Italy invaded and conquered Ethiopia, whom the British had been using to help their effort to put down the Somali uprisings. Now with Ethiopia unavailable, the British were faced with the option of doing the dirty work themselves, or packing up and looking for friendlier territory.

By this time many thousand Italian immigrants were living in Roman-esque villas on extensive plantations in the south. Conditions for natives were unusually prosperous under fascist Italian rule, and the southern Somalis never violently resisted. It had become obvious then that Italy had won the horn of Africa, and Britain left upon Mussolini's insistence, with little protest.

Meanwhile the French colony had faded to obsolescence with Britain's dwindling control, and it to was abandoned. The Italians then enjoyed sole dominance of the entire East African region including Ethiopia, Djibouti, Somalia and parts of northern Kenya.

See also:

World War II

Italian hegemony of Somalia was short-lived, because on the outset of WWII, Mussolini realized he would have to concentrate his resources primarily on the home front to survive the Allied onslaught. As a result the British were able to totally reconquer Somalia by 1941. During the war years, Somalia was directly ruled by a British military administration and martial law was in place, especially in the north where bitter memories of past bloodshed still lingered.

Unfortunately these policies were as ill-advised as they were previously. The irregular bandits and militias of the Somali outback received a windfall in weaponry, thanks to the world wide surge in arms production from the war. The Italian settlers and other anti-British elements made sure the rebels got as many guns as they needed to cause trouble. Despite a fresh Somali thorn in their side, the British protectorate lasted until 1949, and actually made some progress in economic development. The British established their capital in the northern city of Hargeisa, and wisely allowed local Muslim judges to try most cases, rather than impose alien British military justice on the populace.

The British allowed almost all the Italians to stay, except for a few obvious security risks, and regularly employed them as civil servants, and in the educated professions. The fact that 9 out of 10 of the Italians were loyal to Mussolini and probably actively spying on the Italian army's behalf, was tolerated due to Somalia's relative strategic irrelevance to the larger war effort. Indeed, considering they were technically citizens of an enemy power, the British lent considerable leeway to the Italian residents, even allowing them to form their own political parties in direct competiton with British authority.

Post-War Period

After the war, the British gradually relaxed military control of Somalia, and attempted to introduce democracy, and numerous native Somalian political parties sprang into existence, the first being the Somali Youth League (SYL) in 1945. The Potsdam conference was unsure of what to do with Somalia, whether to allow Britain to continue its occupation, to return control to the Italians, who actually had a significant amount of people living there, or grant full independence. This question was hotly debated in the Somalian political scene for the next several years. Many wanted outright independence, especially the rural citizens in the west and north. Southerners enjoyed the economic prosperity brought by the Italians, and preferred their leadership. A smaller faction appreciated Britain's honest attempt to maintain order the second time around, and gave their respect.

Ogaden Granted to Ethiopia

In 1948 a commission led by representatives of the victorious Allied nations wanted to decide the Somalian question once and for all. They made one particular decision, granting Ogaden to Ethiopia, which would spark war decades later. After months of vaciliations and eventually turning the debate over to the United Nations, in 1949 it was decided that in recognition of its genuine economic improvements to the country, Italy would retain a nominal trusteeship of Somalia for the next 10 years, after which it would gain full independence. The SYL, Somalia's first and most powerful party, strongly opposed this decision, preferring immediate independence, and would become a source of unrest in the coming years.

Despite the SYL's misgivings the 1950s were something of a golden age for Somalia. With UN aid money pouring in, and experienced Italian administrators who had come to see Somalia as their home, infrastructural and educational development bloomed. This decade passed relatively without incident and was marked by positive growth in virtually all parts of Somali life. As scheduled, in 1959, Somalia was granted independence, and power transferred smoothly from the Italian administrators to the by then well developed Somali political culture.

Independence

The freshly independent Somalis loved politics, every nomad had a radio to listen to political speeches, and remarkable for a Muslim country, women were also active participants, with only mild mumblings from the more conservative sectors of society. Despite this promising start, there were significant underlying problems, most notably the north/south economic divide and the Ogaden issue. In hindsight it might have made more sense to create two separate countries from the outset, rather than re-uniting the very distinct halves of Somalia and hoping for the best. Also, long held distrust of Ethiopia and the deeply ingrained belief that Ogaden was rightfully part of Somalia, should have been properly addressed prior to independence. The north and south spoke different languages (English vs Italian respectively) had different currencies, and different cultural priorities.

Starting in the early 1960s, troubling trends began to emerge when the north started to reject referendums that had won a majority of votes, based on an overwhelming southern favoritism. This came to a head in 1961 when northern paramilitary organizations revolted when placed under southerners' command. The north's second largest political party began openly advocating secession. Attempts to mend these divides with the formation of a Pan-Somalian party were ineffectual; one opportunistic party attempted to unite the bickering regions by rallying them against their common enemy Ethiopia and the cause of reconquering Ogaden. Other nationalistic party platforms included the independence of the northern Kenyan holdings of the Italian colony, from Kenya proper. These regions were largely inhabited by ethnic Somalis who had become accustomed to Italian rule, and were distressed by the different regime they faced in Kenya.

Clashes with Ethiopia

Somali's internal disputes were manifested outwards in hostility to Ethiopia and Kenya, which they felt were standing in the way of 'Greater Somalia'. This led to a series of individual Somali militiamen conducting hit and run raids across both borders from 1960 to 1964, when open conflict erupted between Ethiopia and Somalia. This lasted a few months until a cease fire was signed in the same year. In the aftermath, Ethiopia and Kenya signed a mutual defense pact to contain Somali aggression.

Although Somalis had received their primary political education under British and post-war Italian tutelage, the virulently anti-Imperialist parties rejected the European's advice whole cloth, and threw their lot in with the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China. By the middle of the 1960s, the Somalis had formal military relationship with Russia whereby the Soviets provided extensive materiel and training to the Somali armed forces. They also had an exchange program in which several hundred soldiers from one country went to the others to train or be trained. As a result of their contact with the Soviet military, many Somali officers gained a distinctly Marxist worldview. China supplied a lot of non military industrial funding for various projects, and the Italians continued to support their displaced children in Africa, and the relationship between the rapidly communizing Somalia and the Italian government remained cordial. The Somalis however were increasingly becoming jaded of the United States, which had been sending substantial military aid to their hostile neighbor, Ethiopia, and thanks to incessant anti-Western indoctrination at the hands of their new Russian friends.

By the late 1960s, the Somali democracy that had gotten off to such an enthusiastic start just ten years prior, was beginning to crumble. In the 1967 election, due to a complicated web of clan loyalties, the winner was not properly recognized and instead a new secret vote was taken by already elected National Assemblymen (senators). The central election issue was whether or not to use military force to bring about the long dreamed of pan-Somalism, which would mean war with Ethiopia and Kenya and possibly Djibouti. In 1968 there seemed to be a brief respite from ominous developments when a telecomunications and trade treaty was worked out with Ethiopia, which was very profitable for both countries, and especially for residents on the border who had been living in a de facto state of emergency since the 1964 cease fire.

1969 was a tumultuous year for Somali politics with even more party defections, collusions, betrayals and collaborations than normal. In a major upset the SYL and its various closely allied supporting parties, which had previously enjoyed a near monopoly of 120 out of 123 seats in the Assembly, saw their power slashed to only 46 seats. This resulted in angry accusations of election fraud from the displaced SYLers, and their remaining members still had the clout to do something about it. Particularly unsettling was that the military was a strong supporter of the SYL, since that party had always been supportive about invading Ethiopia and Kenya, thus giving the military a reason to exist.

Siad Barre's regime

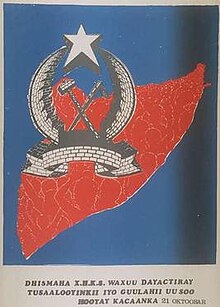

1969 coup d'etat

The stage was set for a coup d'état, but the event that precipitated the coup was unplanned. On 15 October, 1969, a bodyguard killed president Shermarke while prime minister Igaal was out of the country. (The assassin, a member of a lineage said to have been badly treated by the president, was subsequently tried and executed by the revolutionary government.) Igaal returned to Mogadishu to arrange for the selection of a new president by the National Assembly. His choice was, like Shermaarke, a member of the Daarood clan-family (Igaal was an Isaaq). Government critics, particularly a group of army officers, saw no hope for improving the country's situation by this means. Critics also saw the process as extremely corrupt with votes for the presidency being actively bid on, the higbest offer being 55,000 Somali Shillings (approximately $8,000) per vote by Hagi Musa Bogor. On 21 October, 1969, when it became apparent that the assembly would support Igaal's choice, army units, with the cooperation of the police, took over strategic points in Mogadishu and rounded up government officials and other prominent political figures.

Although not regarded as the author of the military takeover, army commander Major General Salad Gabeire Kediye and Mahammad Siad Barre assumed leadership of the officers who deposed the civilian government. The new governing body, the Supreme Revolutionary Council leader Salad Gabeire, installed Siad Barre as its president. The SRC arrested and detained at the presidential palace leading members of the democratic regime, including Igaal. The SRC banned political parties, abolished the National Assembly, and suspended the constitution. The new regime's goals included an end to “tribalism, nepotism, corruption, and misrule”. Existing treaties were to be honored, but national liberation movements and Somali unification were to be supported. The country was renamed the Somali Democratic Republic.

Supreme Revolutionary Council

The SRC also gave priority to rapid economic and social development through "crash programs," efficient and responsive government, and creation of a standard written form of Somali as the country's single official language. The regime pledged continuance of regional détente in its foreign relations without relinquishing Somali claims to disputed territories.

The SRC's domestic program, known as the First Charter of the Revolution, appeared in 1969. Along with Law Number 1, an enabling instrument promulgated on the day of the military takeover, the First Charter provided the institutional and ideological framework of the new regime. Law Number 1 assigned to the SRC all functions previously performed by the president, the National Assembly, and the Council of Ministers, as well as many duties of the courts. The role of the twenty-five-member military junta was that of an executive committee that made decisions and had responsibility to formulate and execute policy. Actions were based on majority vote, but deliberations rarely were published. SRC members met in specialized committees to oversee government operations in given areas. A subordinate fourteen-man secretariat--the Council of the Secretaries of State (CSS)-- functioned as a cabinet and was responsible for day-to-day government operation, although it lacked political power. The CSS consisted largely of civilians, but until 1974 several key ministries were headed by military officers who were concurrently members of the SRC. Existing legislation from the previous democratic government remained in force unless specifically abrogated by the SRC, usually on the grounds that it was "incompatible...with the spirit of the Revolution." In February 1970, the democratic constitution of 1960, suspended at the time of the coup, was repealed by the SRC under powers conferred by Law Number 1.

Although the SRC monopolized executive and legislative authority, Siad Barre filled a number of executive posts: titular head of state, chairman of the CSS (and thereby head of government), commander in chief of the armed forces, and president of the SRC. His titles were of less importance, however, than was his personal authority, to which most SRC members deferred, and his ability to manipulate the clans.

Military and police officers, including some SRC members, headed government agencies and public institutions to supervise economic development, financial management, trade, communications, and public utilities. Military officers replaced civilian district and regional officials. Meanwhile, civil servants attended reorientation courses that combined professional training with political indoctrination, and those found to be incompetent or politically unreliable were fired. A mass dismissal of civil servants in 1974, however, was dictated in part by economic pressures.

The legal system functioned after the coup, subject to modification. In 1970 special tribunals, the National Security Courts (NSC), were set up as the judicial arm of the SRC. Using a military attorney as prosecutor, the courts operated outside the ordinary legal system as watchdogs against activities considered to be counterrevolutionary. The first cases that the courts dealt with involved Shermaarke's assassination and charges of corruption leveled by the SRC against members of the democratic regime. The NSC subsequently heard cases with and without political content. A uniform civil code introduced in 1973 replaced predecessor laws inherited from the Italians and British and also imposed restrictions on the activities of sharia courts. The new regime subsequently extended the death penalty and prison sentences to individual offenders, formally eliminating collective responsibility through the payment of diya or blood money.

The SRC also overhauled local government, breaking up the old regions into smaller units as part of a long-range decentralization program intended to destroy the influence of the traditional clan assemblies and, in the government's words, to bring government "closer to the people." Local councils, composed of military administrators and representatives appointed by the SRC, were established under the Ministry of Interior at the regional, district, and village levels to advise the government on local conditions and to expedite its directives. Other institutional innovations included the organization (under Soviet direction) of the National Security Service (NSS), directed initially at halting the flow of professionals and dissidents out of the country and at counteracting attempts to settle disputes among the clans by traditional means. The newly formed Ministry of Information and National Guidance set up local political education bureaus to carry the government's message to the people and used Somalia's print and broadcast media for the "success of the socialist, revolutionary road." A censorship board, appointed by the ministry, tailored information to SRC guidelines.

The SRC took its toughest political stance in the campaign to break down the solidarity of the lineage groups. Tribalism was condemned as the most serious impediment to national unity. Siad Barre denounced tribalism in a wider context as a "disease" obstructing development not only in Somalia, but also throughout the Third World. The government meted out prison terms and fines for a broad category of proscribed activities classified as tribalism. Traditional headmen, whom the democratic government had paid a stipend, were replaced by reliable local dignitaries known as "peacekeepers" (nabod doan), appointed by Mogadishu to represent government interests. Community identification rather than lineage affiliation was forcefully advocated at orientation centers set up in every district as the foci of local political and social activity. For example, the SRC decreed that all marriage ceremonies should occur at an orientation center. Siad Barre presided over these ceremonies from time to time and contrasted the benefits of socialism to the evils he associated with tribalism.

To increase production and control over the nomads, the government resettled 140,000 nomadic pastoralists in farming communities and in coastal towns, where the erstwhile herders were encouraged to engage in agriculture and fishing. By dispersing the nomads and severing their ties with the land to which specific clans made collective claim, the government may also have undercut clan solidarity. In many instances, real improvement in the living conditions of resettled nomads was evident, but despite government efforts to eliminate it, clan consciousness as well as a desire to return to the nomadic life persisted. Concurrent SRC attempts to improve the status of Somali women were unpopular in a traditional Muslim society, despite Siad Barre's argument that such reforms were consonant with Islamic principles.

Siad Barre and scientific socialism

Somalia's adherence to socialism became official on the first anniversary of the military coup when Siad Barre proclaimed that Somalia was a socialist state, despite the fact that the country had no history of class conflict in the Marxist sense. For purposes of Marxist analysis, therefore, tribalism was equated with class in a society struggling to liberate itself from distinctions imposed by lineage group affiliation. At the time, Siad Barre explained that the official ideology consisted of three elements: his own conception of community development based on the principle of self-reliance, a form of socialism based on Marxist principles, and Islam. These were subsumed under "scientific socialism," although such a definition was at variance with the Soviet and Chinese models to which reference was frequently made.

The theoretical underpinning of the state ideology combined aspects of the Qur'an with the influences of Marx, Lenin, and Mao, but Siad Barre was pragmatic in its application. "Socialism is not a religion," he explained; "It is a political principle" to organize government and manage production. Somalia's alignment with communist states, coupled with its proclaimed adherence to scientific socialism, led to frequent accusations that the country had become a Soviet satellite. For all the rhetoric extolling scientific socialism, however, genuine Marxist sympathies were not deep-rooted in Somalia. But the ideology was acknowledged--partly in view of the country's economic and military dependence on the Soviet Union--as the most convenient peg on which to hang a revolution introduced through a military coup that had supplanted a Western-oriented parliamentary democracy.

More important than Marxist ideology to the popular acceptance of the revolutionary regime in the early 1970s were the personal power of Siad Barre and the image he projected. Styled the "Victorious Leader" (Guulwaadde), Siad Barre fostered the growth of a personality cult. Portraits of him in the company of Marx and Lenin festooned the streets on public occasions. The epigrams, exhortations, and advice of the paternalistic leader who had synthesized Marx with Islam and had found a uniquely Somali path to socialist revolution were widely distributed in Siad Barre's little blue-and-white book. Despite the revolutionary regime's intention to stamp out the clan politics, the government was commonly referred to by the code name MOD. This acronym stood for Marehan (Siad Barre's clan), Ogaden (the clan of Siad Barre's mother), and Dulbahante (the clan of Siad Barre son-in-law Colonel Ahmad Sulaymaan Abdullah, who headed the NSS). These were the three clans whose members formed the government's inner circle. In 1975, for example, ten of the twenty members of the SRC were from the Daarood clan-family, of which these three clans were a part, while the Digil and Rahanweyn, sedentary interriverine clan-families, were totally unrepresented.

The language and literacy issue

One of the principal objectives of the revolutionary regime was the adoption of a standard orthography of the Somali language. Such a system would enable the government to make Somali the country's official language. Since independence Italian and English had served as the languages of administration and instruction in Somalia's schools. All government documents had been published in the two European languages. Indeed, it had been considered necessary that certain civil service posts of national importance be held by two officials, one proficient in English and the other in Italian. During the Husseen and Igaal governments, when a number of English-speaking northerners were put in prominent positions, English had dominated Italian in official circles and had even begun to replace it as a medium of instruction in southern schools. Arabic—or a heavily arabized Somali—also had been widely used in cultural and commercial areas and in Islamic schools and courts. Religious traditionalists and supporters of Somalia's integration into the Arab world had advocated that Arabic be adopted as the official language, with Somali as a vernacular.

A few months after independence, the Somali Language Committee was appointed to investigate the best means of writing Somali. The committee considered nine scripts, including Arabic, Latin, and various indigenous scripts. Its report, issued in 1962, favored the Latin script, which the committee regarded as the best suited to represent the phonemic structure of Somali and flexible enough to be adjusted for the dialects. Facility with a Latin system, moreover, offered obvious advantages to those who sought higher education outside the country. Modern printing equipment would also be more easily and reasonably available for Latin type. Existing Somali grammars prepared by foreign scholars, although outdated for modern teaching methods, would give some initial advantage in the preparation of teaching materials. Disagreement had been so intense among opposing factions, however, that no action was taken to adopt a standard script, although successive governments continued to reiterate their intention to resolve the issue.

On coming to power, the SRC made clear that it viewed the official use of foreign languages, of which only a relatively small fraction of the population had an adequate working knowledge, as a threat to national unity, contributing to the stratification of society on the basis of language. In 1971 the SRC revived the Somali Language Committee and instructed it to prepare textbooks for schools and adult education programs, a national grammar, and a new Somali dictionary. However, no decision was made at the time concerning the use of a particular script, and each member of the committee worked in the one with which he was familiar. The understanding was that, upon adoption of a standard script, all materials would be immediately transcribed.

On the third anniversary of the 1969 coup, the SRC announced that a Latin script had been adopted as the standard script to be used throughout Somalia beginning January 1, 1973. As a prerequisite for continued government service, all officials were given three months (later extended to six months) to learn the new script and to become proficient in it. During 1973 educational material written in the standard orthography was introduced in elementary schools and by 1975 was also being used in secondary and higher education.

Somalia's literacy rate was estimated at only 5 percent in 1972. After adopting the new script, the SRC launched a "cultural revolution" aimed at making the entire population literate in two years. The first part of the massive literacy campaign was carried out in a series of three-month sessions in urban and rural sedentary areas and reportedly resulted in several hundred thousand people learning to read and write. As many as 8,000 teachers were recruited, mostly among government employees and members of the armed forces, to conduct the program.

The campaign in settled areas was followed by preparations for a major effort among the nomads that got underway in August 1974. The program in the countryside was carried out by more than 20,000 teachers, half of whom were secondary school students whose classes were suspended for the duration of the school year. The rural program also compelled a privileged class of urban youth to share the hardships of the nomadic pastoralists. Although affected by the onset of a severe drought, the program appeared to have achieved substantial results in the field in a short period of time. Nevertheless, the UN estimate of Somalia's literacy rate in 1990 was only 24 percent.

Creation of the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party

One of the SRC's first acts was to prohibit the existence of any political association. Under Soviet pressure to create a communist party structure to replace Somalia's military regime, Siad Barre had announced as early as 1971 the SRC's intention to establish a one-party state. The SRC already had begun organizing what was described as a "vanguard of the revolution" composed of members of a socialist elite drawn from the military and the civilian sectors. The National Public Relations Office (retitled the National Political Office in 1973) was formed to propagate scientific socialism with the support of the Ministry of Information and National Guidance through orientation centers that had been built around the country, generally as local selfhelp projects.

The SRC convened a congress of the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP) in June 1976 and voted to establish the Supreme Council as the new party's central committee. The council included the nineteen officers who composed the SRC, in addition to civilian advisers, heads of ministries, and other public figures. Civilians accounted for a majority of the Supreme Council's seventy-three members. On July 1, 1976, the SRC dissolved itself, formally vesting power over the government in the SRSP under the direction of the Supreme Council.

In theory the SRSP's creation marked the end of military rule, but in practice real power over the party and the government remained with the small group of military officers who had been most influential in the SRC. Decision-making power resided with the new party's politburo, a select committee of the Supreme Council that was composed of five former SRC members, including Siad Barre and his son-in-law, NSS chief Abdullah. Siad Barre was also secretary general of the SRSP, as well as chairman of the Council of Ministers, which had replaced the CSS in 1981. Military influence in the new government increased with the assignment of former SRC members to additional ministerial posts. The MOD circle also had wide representation on the Supreme Council and in other party organs. Upon the establishment of the SRSP, the National Political Office was abolished; local party leadership assumed its functions.

Ogaden War

In 1977 the Somali president, Siad Barre, was able to muster 35,000 regulars and 15,000 fighters of the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF). His forces began infiltrating into the Ogaden in May-June 1977, and overt warfare began in July. By September 1977 Mogadishu controlled 90 percent of the Ogaden and had followed retreating Ethiopian forces into non-Somali regions of Harerge, Bale, and Sidamo.

After watching Ethiopian events in 1975-76, the Soviet Union concluded that the revolution would lead to the establishment of an authentic Marxist-Leninist state and that, for geopolitical purposes, it was wise to transfer Soviet interests to Ethiopia. To this end, Moscow secretly promised the Derg military aid on condition that it renounce the alliance with the United States. Mengistu Haile Mariam, believing that the Soviet Union's revolutionary history of national reconstruction was in keeping with Ethiopia's political goals, closed down the U.S. military mission and the communications centre in April 1977. In September, Moscow suspended all military aid to Somalia, and began openly deliver weapons to Addis Ababa, and reassigned military advisers from Somalia to Ethiopia. This Soviet volte-face also gained Ethiopia important support from North Korea, which trained a People's Militia, and from Cuba and the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen, which provided infantry, pilots, and armoured units. Somalia renounced the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union expelled all Soviet advisers, broke diplomatic relations with Cuba, and ejected all Soviet personnel from Somalia

By March 1978, Ethiopia and its allies regained control over the Ogaden. Siad Barre proved unable to return the Ogaden to Somali rule, and the people grew restive; in northern Somalia, rebels destroyed administrative centres and took over major towns. Both Ethiopia and Somalia had followed ruinous socialist policies of economic development, and they were unable to surmount droughts and famines that afflicted the Horn during the 1980s. In 1988 Siyaad and Mengistu agreed to withdraw their armies from possible confrontation in the Ogaden.

Somalia, 1980-90

Entrenching Siad Barre's personal rule

The Ogaden War of 1977-78 between Somalia and Ethiopia and the consequent refugee influx forced Somalia to depend for its economic survival on humanitarian handouts. Domestically, the lost war produced a national mood of depression. Organized opposition groups began to emerge, and in dealing with them Siad Barre intensified his political repression, using jailings, torture, and summary executions of dissidents and collective punishment of clans thought to have engaged in organized resistance.

Siad Barre's new Western friends, especially the United States, which had replaced the Soviet Union as the main user of the naval facilities at Berbera, turned out to be reluctant allies. Although prepared to help the Siad Barre regime economically through direct grants, World Bank-sponsored loans, and relaxed International Monetary Fund regulations, the United States hesitated to offer Somalia more military aid than was essential to maintain internal security. The amount of United States military and economic aid to the regime was US$34 million in 1984; by 1987 this amount had dwindled to about US$8.7 million, a fraction of the regime's requested allocation of US$47 million. Western countries were also pressuring the regime to liberalize economic and political life and to renounce historical Somali claims on territory in Kenya and Ethiopia. In response, Siad Barre held parliamentary elections in December 1979. A "people's parliament" was elected, all of whose members belonged to the government party, the SRSP. Following the elections, Siad Barre again reshuffled the cabinet, abolishing the positions of his three vice presidents. This action was followed by another reshuffling in October 1980 in which the old Supreme Revolutionary Council was revived. The move resulted in three parallel and overlapping bureaucratic structures within one administration: the party's politburo, which exercised executive powers through its Central Committee, the Council of Minsters, and the SRC. The resulting confusion of functions within the administration left decision making solely in Siad Barre's hands.

In February 1982, Siad Barre visited the United States. He had responded to growing domestic criticism by releasing from detention two leading political prisoners, former premier Igaal and former police commander Abshir, both of whom had been in prison since 1969. On June 7, 1982, apparently wishing to prove that he alone ruled Somalia, Siad ordered the arrest of seventeen prominent politicians. This development shook the "old establishment" because the arrests included Mahammad Aadan Shaykh, a prominent Mareehaan politician, detained for the second time; Umar Haaji Masala, chief of staff of the military, also a Mareehaan; and a former vice president and a former foreign minister. At the time of detention, one official was a member of the politburo; the others were members of the Central Committee of the SRSP. The jailing of these prominent figures created an atmosphere of fear, and alienated some clans, whose disaffection and consequent armed resistance were to lead to the toppling of the Siad Barre regime.

Political insecurity was considerably increased by repeated forays across the Somali border in the Mudug and Boorama regions by a combination of Somali dissidents and Ethiopian army units. In mid-July 1982, Somali dissidents with Ethiopian air support invaded Somalia in the center, threatening to split the country in two. The invaders managed to capture the Somali border towns of Balumbale and Galdogob, northwest of the Mudug regional capital of Galcaio. The government declared a state of emergency in the war zone and appealed for Western aid to help repel the invasion. The United States government responded by speeding deliveries of light arms already promised. In addition, the initially pledged US$45 million in economic and military aid was increased to US$80 million. The new arms were not used to repel the Ethiopians, however, but to repress Siad Barre's domestic opponents.

Although the Siad Barre regime received some verbal support at the League of Arab States summit conference in September 1982, and Somali units participated in war games with the United States Rapid Deployment Force in Berbera, the revolutionary government's position continued to erode. In December 1984, Siad Barre sought to broaden his political base by amending the constitution. One amendment extended the president's term from six to seven years. Another amendment stipulated that the president was to be elected by universal suffrage (Siad Barre always received 99 percent of the vote in such elections) rather than by the National Assembly. The assembly rubber-stamped these amendments, thereby presiding over its own disenfranchisement.

On the diplomatic front, the regime undertook some fence mending. An accord was signed with Kenya in December 1984 in which Somalia "permanently" renounced its historical territorial claims, and relations between the two countries thereafter began to improve. This diplomatic gain was offset, however, by the "scandal" of South African foreign minister Roelof "Pik" Botha's secret visit to Mogadishu that same month, where he promised arms to Somalia in return for landing rights for South African Airways.

Complicating matters for the regime, at the end of 1984 the Western Somali Liberation Front (WSLF) announced a temporary halt in military operations against Ethiopia. This decision was impelled by the drought then ravaging the Ogaden and by a serious split within the WSLF, a number of whose leaders claimed that their struggle for self-determination had been used by Mogadishu to advance its expansionist policies. These elements said they now favored autonomy based on a federal union with Ethiopia. This development removed Siad Barre's option to foment anti-Ethiopian activity in the Ogaden in retaliation for Ethiopian aid to domestic opponents of his regime.

To overcome its diplomatic isolation, Somalia resumed relations with Libya in April 1985. Recognition had been withdrawn in 1977 in response to Libyan support of Ethiopia during the Ogaden War. Also in early 1985 Somalia participated in a meeting of EEC and UN officials with the foreign ministers of several northeast African states to discuss regional cooperation under a planned new authority, the Inter-Governmental Authority on Drought and Development (IGAD). Formed in January 1986 and headquartered in Djibouti, IGAD brought together Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, and Uganda in addition to Somalia. In January 1986, under the auspices of IGAD, Siad Barre met Ethiopian leader Mengistu Haile Mariam in Djibouti to discuss the undemarcated boundary between Ethiopia and Somalia. They agreed to hold further meetings, which took place on and off throughout 1986-87. Although Siad Barre and Mengistu agreed to exchange prisoners taken in the Ogaden War and to cease aiding each other's domestic opponents, these plans were never implemented. In August 1986, Somalia held joint military exercises with the United States.

Diplomatic setbacks also occurred in 1986, however. In September, Somali foreign minister Abdirahmaan Jaama Barre, the president's brother, accused the Somali Service of the British Broadcasting Corporation of anti-Somali propaganda. The charge precipitated a diplomatic rift with Britain. The regime also entered into a dispute with Amnesty International, which charged the Somali regime with blatant violations of human rights. Wholesale human rights violations documented by Amnesty International, and subsequently by Africa Watch, prompted the United States Congress by 1987 to make deep cuts in aid to Somalia.

Economically, the regime was repeatedly pressured between 1983 and 1987 by the IMF, the United Nations Development Programme, and the World Bank to liberalize its economy. Specifically, Somalia was urged to create a free market system and to devalue the Somali shilling so that its official rate would reflect its true value.

Repression

Faced with shrinking popularity and an armed and organized domestic resistance, Siad Barre unleashed a reign of terror against the Majeerteen, the Hawiye, and the Isaaq, carried out by the Red Berets (Duub Cas), a special unit recruited from the president's Marehan clansmen. Thus, by the beginning of 1986 Siad Barre's grip on power seemed secure, despite the host of problems facing the regime. The president received a severe blow from an unexpected quarter, however. On the evening of May 23, he was severely injured in an automobile accident. Astonishingly, although at the time he was in his early seventies and suffered from chronic diabetes, Siad Barre recovered sufficiently to resume the reins of government following a month's recuperation. But the accident unleashed a power struggle among senior army commandants, elements of the president's Marehan clan, and related factions, whose infighting practically brought the country to a standstill. Broadly, two groups contended for power: a constitutional faction and a clan faction. The constitutional faction was led by the senior vice president, Brigadier General Mahammad Ali Samantar; the second vice president, Major General Husseen Kulmiye; and generals Ahmad Sulaymaan Abdullah and Ahmad Mahamuud Faarah. The four, together with president Siad Barre, constituted the politburo of the SRSP.

Opposed to the constitutional group were elements from the president's Marehan clan, especially members of his immediate family, including his brother, Abdirahmaan Jaama Barre; the president's son, Colonel Masleh Siad, and the formidable Mama Khadiija, Siad Barre's senior wife. By some accounts, Mama Khadiija ran her own intelligence network, had well-placed political contacts, and oversaw a large group who had prospered under her patronage.

In November 1986, the dreaded Red Berets unleashed a campaign of terror and intimidation on a frightened citizenry. Meanwhile, the ministries atrophied and the army's officer corps was purged of competent career officers on suspicion of insufficient loyalty to the president. In addition, ministers and bureaucrats plundered what was left of the national treasury after it had been repeatedly skimmed by the top family.

The same month, the SRSP held its third congress. The Central Committee was reshuffled and the president was nominated as the only candidate for another seven-year term. Thus, with a weak opposition divided along clan lines, which he skillfully exploited, Siad Barre seemed invulnerable well into 1988. The regime might have lingered indefinitely but for the wholesale disaffection engendered by the genocidal policies carried out against important lineages of Somali kinship groupings. These actions were waged first against the Majeerteen clan (of the Darod clan-family), then against the Isaaq clans of the north, and finally against the Hawiye, who occupied the strategic central area of the country, which included the capital. The disaffection of the Hawiye and their subsequent organized armed resistance eventually caused the regime's downfall.

Somali Civil War

In May of 1991, the northern portion of the country declared its independence as Somaliland; although de facto independent and relatively stable compared to the tumultuous south, it has not been recognized by any foreign government. UN Security Council Resolution 794 was unanimously passed on December 3, 1992, which approved a coalition of United Nations peacekeepers led by the United States to form UNITAF, tasked with ensuring humanitarian aid being distributed and peace being established in Somalia. The UN humanitarian troops landed in 1993 and started a two-year effort (primarily in the south) to alleviate famine conditions.

Many Somalis opposed the foreign presence. In October, several gun battles in Mogadishu between local gunmen and peacekeepers resulted in the death of 24 Pakistanis and 19 US soldiers (total US deaths were 31). Most of the Americans were killed in the Battle of Mogadishu. The incident later became the basis for the book and movie Black Hawk Down. The UN withdrew on March 3, 1995, having suffered more significant casualties. Order in Somalia still has not been restored.

Yet again another secession from Somalia took place in the northeastern region. The self-proclaimed state took the name Puntland after declaring "temporary" independence in 1998, with the intention that it would participate in any Somali reconciliation to form a new central government.

A third secession occurred in 1998 with the declaration of the state of Jubaland. The territory of Jubaland is now encompassed by the state of Southwestern Somalia and its status is unclear.

A fourth self-proclaimed entity led by the Rahanweyn Resistance Army (RRA) was set up in 1999, along the lines of the Puntland. That "temporary" secession was reasserted in 2002. This led to the autonomy of Southwestern Somalia. The RRA had originally set up an autonomous administration over the Bay and Bakool regions of south and central Somalia in 1999.

Recent history

The various Somali militias have developed into security agencies for hire. Due to that development security has much improved and an economic rebound occurred. It can be said that Somalia is now partly in a state of anarcho-capitalism where all services are provided by private ventures. According to CIA factbook Somali telecommunication firms provide wireless services in most major cities and offer the lowest international call rates on the continent.

On October 10, 2004 Somali parliament members elected Abdullahi Yusuf, president of Puntland, to be the next president. Because of the chaotic situation in Mogadishu, a decision was made to hold the election in the relatively atypical venue of a sports centre in Nairobi, Kenya.

Indian Ocean Tsunami

On December 26 2004, one of the deadliest natural disasters in modern history, the Indian Ocean earthquake, struck off the western coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. The earthquake and subsequent tsunamis reportedly killed over 220,000 people around the rim of the Indian Ocean. Somalia's east coast was affected. 298 people were reportedly killed but relief workers dispute this figure as overstated.[4]

Civil War

Starting in May 2006 with the Second Battle of Mogadishu, civil war wracked Somalia as the Islamic Courts Union (ICU) fought with warlords, pirates, other separatists, the internationally-backed Transitional Federal Government (TFG) and Ethiopian troops to bring unity, security and Sharia law to Somalia. On June 5, 2006 forces associated with the Islamic Court Union claimed to have taken control of Mogadishu.

The transitional government in Baidoa tried to secure the help of African Union peacekeeping troops to help pacify Somalia so that a government can survive and hold power with some stability. This proposal has been controversial, because of bringing foreign troops in the country since 1995 when the United Nations troops left Somalia. Some of the countries contributing troops are also not popular locally, Ethiopia especially. The warlords in Mogadishu have actually united to fight any foreign troops, as the speaker of the parliament allied with the warlords, causing a fault line in the government. Some of the war lords are aligned with Islamic miltant groups, and the US government accuses the involvement of al-Qaeda amongst the ICU leaders. Instability, warlord control, piracy and economic chaos remain significant issues in many parts of the country.[5]

Timeline

Ancient

Muslim Era

- 700 - 1000 AD: the Port cities in Somalia trade with arab traders and convert to Islam

- 1300 - 1400 AD: the prosperous Somali city states are visited by Ibn Battuta and Zheng he

- 1500 - 1660: the Rise and Fall of Adal Sultanate.

- 1528 - 1535: Jihad against Ethiopia led by Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi, also called Ahmed Gurey or Ahmed Gran (the Left-handed)[1]

- 1400 - 1700: the Rise and Fall of the Ajuuraan Dynasty

- 1800 - 1900: Geledi Sultanate/Hobyo Sultanate

Colonial Era

- 20 Jul 1887 : British Somaliland protectorate (in the north) subordinated to Aden to 1905.

- 3 Aug 1889: Benadir Coast Italian Protectorate (in the northeast), (unoccupied until May 1893).

- 1900: Mohammed Abdullah Hassan spearheads a somali war against foreigners

- 16 Mar 1905: Italian Somalia (Italian Somaliland) colony (in the northeast and in the south).

- Jul 1910: Italian Somaliland a crown colony.

- 1920: Mohammed Abdullah Hassan (called "the Mad Mullah" by the British) dies and the longest and bloodiest colonial resistance war in Africa ends.

- 15 Jan 1935: Italian Somalia Part of Italian East Africa with It. Eritrea (and from 1936 Ethiopia).

- 1 Jun 1936: Part of Italian East Africa (province of Somalia, formed by the merger of the colony and the Ethiopian region of Ogaden; see Ethiopia).

World War II

- 18 Aug 1940: Italian occupation of British Somaliland.

- Feb 1941: British administration of Italian Somalia.

Independence and Cold War

- 1 Apr 1950: Italian Somalia becomes United Nations trust territory under Italian administration.

- 26 Jun 1960: Independence of British Somaliland as the State of Somaliland.

- 1 Jul 1960: Unification of Somaliland with Italian Somalia to form the Somali Republic.

- 1960 - 1967: Presidency of Aden Abdullah Osman Daar

- 1967 - 1969: Presidency of Abdirashid Ali Shermarke; assassinated by a police officer.

- 21 Oct 1969: Somali Democratic Republic

- 1969 - 1991: Mohamed Siad Barre rises to power in a coup d'etat after the assassination of Abdirashid Ali Shermarke. Remains head of state of Somalia until forced from power by General Mohamed Farrah Aidid. Barre dies in exile of a heart attack in 1995.

- 23 July 1977 - 15 March 1978: Ogaden War

Modern Era

- 1991 - 1996: General Mohamed Farrah Aidid, leader of the United Somali Congress (USC) and later Somali National Alliance (SNA), is the strongest of the vying warlords. He opposes US intervention in Somalia and is the subject of the raid which led to the Battle of Mogadishu, also known as the "Blackhawk Down" incident. In 1996 he dies of gunshot wounds while fighting against a rival faction.

- 1 Jan 1991: Somalia collapses, no single functioning government.

- 18 May 1991: Secession of former British Somaliland; as Republic of Somaliland which is proclaimed 24 May 1991 (not internationally recognized).

- 21 Jul 1991: Somali Republic

- April - November 1992: UNOSOM I is the initial UN humanitarian mission to provide relief to famine-plagued and war-torn Somalia.

- 3 December 1992 - 4 May 1993: Operation Restore Hope is the name for the UN-sanctioned US military intervention in Somalia, known as UNITAF. Friction with Mohamed Farrah Aidid culminates in the Battle of Mogadishu.

- March 1993 - March 1995: UNOSOM II is the follow-on UN humanitarian mission.