Lake Van

| Lake Van | |

|---|---|

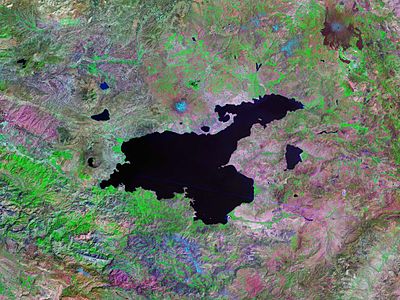

From space, 2000 | |

| Location | Armenian highlands Western Asia |

| Coordinates | 38°38′N 42°49′E / 38.633°N 42.817°E |

| Type | Tectonic lake, saline lake |

| Primary inflows | Karasu, Hoşap, Bendimahi, Zilan and Yeniköprü streams[1] |

| Primary outflows | none |

| Catchment area | 12,500 km2 (4,800 sq mi)[1] |

| Basin countries | Turkey |

| Max. length | 119 km (74 mi) |

| Surface area | 3,755 km2 (1,450 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 171 m (561 ft) |

| Max. depth | 451 m (1,480 ft)[2] |

| Water volume | 642.1 km3 (154.0 cu mi)[2] |

| Shore length1 | 430 km (270 mi) |

| Surface elevation | 1,640 m (5,380 ft) |

| Islands | Akdamar, Çarpanak (Ktuts), Adır (Lim), Kuş (Arter) |

| Settlements | Van, Tatvan, Ahlat, Adilcevaz, Erciş |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

Lake Van (Turkish: Van Gölü; Armenian: Վանա լիճ, romanized: Vana lič̣; Kurdish: Gola Wanê[3]) is the largest lake in Turkey.[4][5] It lies in the Eastern Anatolia Region of Turkey in the provinces of Van and Bitlis. It is a saline soda lake, receiving water from many small streams that descend from the surrounding mountains. It is one of the world's few endorheic lakes (a lake having no outlet) of size greater than 3,000 square kilometres (1,200 sq mi) and has 38% of the country's surface water (including rivers). A volcanic eruption blocked its original outlet in prehistoric times. It is situated at 1,640 m (5,380 ft) above sea level. Despite the high altitude and winter averages below 0 °C (32 °F), high salinity usually prevents it from freezing; the shallow northern section can freeze, but rarely.[6]

Hydrology and chemistry

Lake Van is 119 kilometres (74 mi) across at its widest point. It averages 171 metres (561 ft) deep. Its greatest known depth is 451 metres (1,480 ft).[2] The surface lies 1,640 metres (5,380 ft) above sea level and the shore length is 430 kilometres (270 mi). It covers 3,755 km2 (1,450 sq mi) and contains (has a volume of) 607 cubic kilometres (146 cu mi).[2]

The western portion of the lake is deepest, with a large basin deeper than 400 m (1,300 ft) lying northeast of Tatvan and south of Ahlat. The eastern arms of the lake are shallower. The Van-Ahtamar portion shelves gradually, with a maximum depth of about 250 m (820 ft) on its northwest side where it joins the rest of the lake. The Erciş arm is much shallower, mostly less than 50 m (160 ft), with a maximum depth of about 150 m (490 ft).[7][8]

The lake water is strongly alkaline (pH 9.7–9.8) and rich in sodium carbonate and other salts. Some is extracted in salt evaporation ponds alongside, used in or as detergents.[9]

Geology

Lake Van is primarily a tectonic lake, formed more than 600,000 years ago by the gradual subsidence of a large block of the Earth's crust due to movement on several major faults that run through this portion of Eastern Anatolia. The lake's southern margin demarcates: a metamorphic rock zone of the Bitlis Massif and volcanic strata of the Neogene and Quaternary periods. The deep, western portion of the lake is an antidome basin in a tectonic depression. This was formed by normal and strike-slip faulting and thrusting.[10]

The lake's proximity to the Karlıova triple junction has led to molten fluids of the Earth's mantle accumulating in the strata beneath, still driving gradual change.[10] Dominating the lake's northern shore is the stratovolcano Mount Süphan. The broad crater of a second, dormant volcano, Mount Nemrut, is close to the western tip of the lake. There is hydrothermal activity throughout the region.[10]

For much of its history, until the Pleistocene, Lake Van has had an outlet towards the southwest (into the Murat River and eventually into the Euphrates river). However, the level of this threshold has varied over time, as the lake has been blocked by successive lava flows from Nemrut volcano westward towards the Muş Plain. This threshold has then been lowered at times by erosion.

Bathymetry

The first acoustic survey of Lake Van was performed in 1974.[7][11]

Kempe and Degens later identified three physiographic provinces comprising the lake:

- a lacustrine shelf (27% of the lake) from the shore to a clear gradient change

- a steeper lacustrine slope (63%)

- a deep, relatively flat basin province (10%) in the western center of the lake.[12]

The deepest part of the lake is the Tatvan basin, which is almost completely bounded by faults.[11]

Prehistoric lake levels

Land terraces (remnant dry, upper banks from previous shorelines) above the present shore have long been recognized. On a visit in 1898, geologist Felix Oswald noted three raised beaches at 15, 50 and 100 feet (5, 15 and 30 meters) above the lake then, as well as recently drowned trees.[13] Research in the past century has identified many similar terraces, and the lake's level has fluctuated significantly during that time.

As the lake has no outlet, the level over recent millennia rests on inflow and evaporation.

The water level has vacillated greatly. Investigation by a team including Degens in the early 1980s determined that the highest lake levels (72 metres (236 ft) above the current height) had been during the last ice age, about 18,000 years ago. Approximately 9,500 years ago there was a dramatic drop to more than 300 metres (980 ft) below the present level. This was followed by an equally-dramatic rise around 6,500 years ago.[2]

As a deep lake with no outlet, Lake Van has accumulated great amounts of sediment washed in from surrounding plains and valleys, and occasionally deposited as ash from eruptions of nearby volcanoes. This layer of sediment is estimated to be up to 400 metres (1,300 ft) thick in places, and has attracted climatologists and vulcanologists interested in drilling cores to examine the layered sediments.

In 1989 and 1990, an international team of geologists led by Stephan Kempe from the University of Hamburg[a] retrieved ten sediment cores from depths up to 446 m (1,463 ft). Although these cores only penetrated the first few meters of sediment, they provided sufficient varves to give proxy climate data for up to 14,570 years BP.[14]

A team of scientists headed by palaeontologist Professor Thomas Litt at the University of Bonn has applied for funding from the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program (ICDP) for an akin deeper-drilling project. This expects to find it "stores the climate history of the last 800,000 years—an incomparable treasure house of data which we want to tap for at least the last 500,000 years."[15] A test drilling in 2004 detected evidence of 15 volcanic eruptions in the past 20,000 years.

Recent lake level change

Similar but smaller fluctuations have been seen recently. The level of the lake rose by at least 3 m (9.8 ft) during the 1990's, drowning much agricultural land, and (after a brief period of stability and then retreat) seems to be rising again. The level rose approximately 2 m (6.6 ft) in the 10 years immediately prior to 2004.[1] But in the early 2020s it fell.[16]

Climate

Lake Van is in the highest and largest region of Turkey, which has a Mediterranean-influenced humid continental climate. Average temperatures in July are between 22 and 25 °C, and in January between −3 °C to −12 °C. On some cold winter nights the temperature has reached −30 °C.

The lake, particularly on its urban townscape shore, tempers the climate in the city of Van, where the average temperature in July is 22.5 °C, and in January −3.5 °C. The average annual rainfall in the basin ranges from 400 to 700 mm.[17][18]

Ecology

Prior to 2018, the only fish known to live in the brackish water of Lake Van was Alburnus tarichi or Pearl Mullet (Turkish: inci kefali), a Cyprinid fish related to chub and dace, which is caught during the spring floods.[19] In May and June, these fish migrate from the lake to less alkaline water, spawning either near the mouths of the rivers feeding the lake or in the rivers themselves. After spawning season it returns to the lake.[20] In 2018, a new species of fish, which is deemed as Oxynoemacheilus ercisianus, has been discovered inside a microbialite.[21][22]

103 species of phytoplankton have been recorded in the lake including cyanobacteria, flagellates, diatoms, green algae, and brown algae. 36 species of zooplankton have also been recorded including Rotatoria, Cladocera, and Copepoda in the lake.[23]

In 1991, researchers reported the discovery of 40 m (130 ft) tall microbialites in the lake. These are solid towers on the lake bed formed by coccoid cyanobacteria (Pleurocapsa group), which create mats of aragonite that combine with calcite precipitating out of the lake water.[24]

The region hosts the rare Van cat breed of cat, having – among other things – an unusual fascination with water. The lake is mainly surrounded by fruit orchards and grain fields, interspersed by some non-agricultural trees.

Monster myth

According to legend, the lake hosts the mysterious Lake Van Monster that lurks below the surface, 30-to-40 ft (9-to-12 m) long with brown scaly skin, an elongated reptilian head and flippers. Apart from some inconclusive amateur photographs and videos, there has never been any evidence of it. The claimed profile resembles an extinct mosasaurus or basilosaurus.

History

Tushpa, the capital of Urartu, near the shores, on the site of what became medieval Van's castle, west of present-day Van city.[25] The ruins of the medieval city of Van are still visible below the southern slopes of the rock on which Van Castle stands.

In 2017, archaeologists from Van Yüzüncü Yil University and a team of independent divers who were exploring Lake Van reported the discovery of a large underwater fortress spanning roughly one kilometer.[26] The team estimates that this fortress was constructed during the Urartian period, based on their visual assessments. The archaeologists believe that the fortress, along with other parts of the ancient city that surrounded it at the time, had slowly become submerged over the millennia by the gradually rising lake.[27]

Armenian kingdoms

The lake was the centre of the kingdom of Urartu from about 1000 BC, afterwards of the Satrapy of Armenia, Kingdom of Greater Armenia, and the Armenian Kingdom of Vaspurakan.

Along with Lake Sevan in today's Armenia and Lake Urmia in today's Iran, Van was one of the three great lakes of the Armenian Kingdom, referred to as the seas of Armenia (in ancient Assyrian sources: "tâmtu ša mât Nairi" (Upper Sea of Nairi), the Lower Sea being Lake Urmia).[28] Over time, the lake was known by various Armenian names, including Armenian: Վանա լիճ (Lake of Van), Վանա ծով (Sea of Van), Արճեշի ծով (Sea of Arčeš), Բզնունեաց ծով (Sea of Bznunik),[29] Ռշտունեաց ծով (Sea of Rshtunik),[29] and Տոսպայ լիճ (Lake of Tosp).

Eastern Roman Empire

By the 11th century the lake was on the border between the Eastern Roman Empire, with its capital at Constantinople, and the Turko-Persian Seljuk Empire, with its capital at Isfahan. In the uneasy peace between the two empires, local Armenian-Byzantine landowners employed Turcoman gazis and Byzantine akritai for protection. The Greek-speaking Byzantines called the lake Thospitis limne (Medieval Greek: Θωσπῖτις λίμνη).

In the second half of the 11th century Emperor Romanus IV Diogenes launched a campaign to re-conquer Armenia and head off growing Seljuk control. Diogenes and his large army crossed the Euphrates and confronted a much smaller Seljuk force led by Alp Arslan at the Battle of Manzikert, north of Lake Van on 26 August 1071. Despite their greater numbers, the cumbersome Byzantine force was defeated by the more mobile Turkish horsemen and Diogenes was captured.

Seljuk Empire

Alp Arslan divided the conquered eastern portions of the Byzantine empire among his Turcoman generals, with each ruled as a hereditary beylik, under overall sovereignty of the Seljuq Empire. Alp Arslan gave the region around Lake Van to his commander Sökmen el-Kutbî, who set up his capital at Ahlat on the western side of the lake. The dynasty of Shah-Armens, also known as Sökmenler, ruled this area from 1085 to 1192.

The Ahlatshahs were succeeded by the Ayyubid dynasty.

Ottoman Empire

Following the disintegration of the Seljuq-ruled Sultanate of Rum, Lake Van and its surroundings were conquered by the Ilkhanate Mongols, and later switched hands between the Ottoman Empire and Safavid Iran until Sultan Selim I took control for good.

Reports of the Lake Van Monster surfaced in the late 1800's and gained popularity. A news article was published by Saadet Gazetesi issue number 1323, dated 28 Shaban 1306 Hijri year, corresponding to 29 April 1889 during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II.[31]

Architecture

Near the Van Fortress and the southern shore, on Akdamar Island lies the 10th century Cathedral of the Holy Cross, Aghtamar (Armenian: Սուրբ Խաչ, Surb Khach), which served as a royal church to the kingdom of Vaspurakan.[citation needed] The ruins of Armenian monasteries also exist on the other three islands of Lake Van: Lim, Arter, and Ktuts. The area around Lake Van was also the home to a large number of Armenian monasteries, among the most prominent of these being the 10th century Narekavank and the 11th century Varagavank, the former now destroyed.[citation needed]

The Ahlatshahs left a large number of historic headstones in and around the town of Ahlat. Local administrators are currently trying to have the tombstones included in UNESCO's World Heritage List, where they are currently listed tentatively.[32][33]

Transportation

The railway connecting Turkey and Iran was built in the 1970's, sponsored by CENTO. It uses a train ferry (ferry for decanted passengers) across between the cities Tatvan and Van, rather than building tracks around rugged terrain. This limits passenger capacity. In May 2008, talks started between Turkey and Iran to replace the ferry with a double-track electrified railway.[34]

In December 2015, the new generation of train ferries operated by the Turkish State Railways, the largest of their kind in Turkey, entered service in Lake Van.[30]

Ferit Melen Airport abuts Van. Turkish Airlines, AnadoluJet, Pegasus Airlines, and SunExpress are the airlines which have regular flights.

Sports

Lake Van occasionally hosts several water sports, sailing, and inshore powerboat racing events, such as the UIM World Offshore 225 Championship's IOC Van Grand Prix, and the Van Lake Festival.

Islands and nearby lakes

Islands

The four main islands in Lake Van are Adır, Akdamar, Çarpanak, and Kuş islands. Adır Island is the biggest Island in Lake Van.

Each island has Armenian religious structures: Lim Monastery (Adır Island), Holy Cross Cathedral (Akdamar Island), Ktuts monastery (Çarpanak Island) and a small monastery on Kuş Island.

Nearby Lakes

Large lakes near Lake Van are Lake Erçek (16km), Lake Turna (23km), Lake Nemrut (12km), Lake Nazik (16km), Lake Batmış (10km), Lake Aygır (5km) and Lake Süphan (18km). Lake Erçek is by far the biggest, with an area of 106.2 square kilometres (41.0 sq mi),[35] and is the second biggest Van Province.

See also

Notes

- ^ Later Professor at the Technische Universität Darmstadt

References

- ^ a b c Coskun & Musaoğlu 2004.

- ^ a b c d e Degens et al. 1984.

- ^ "Van Gölü – Turkey from the Inside". 28 April 2024. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ Meiklejohn, John Miller Dow (1895). A New Geography on the Comparative Method, with Maps and Diagrams and an Outline of Commercial Geography (14 ed.). A. M. Holden. p. 306.

- ^ Olson, James S.; Pappas, Lee Brigance; Pappas, Nicholas C. J., eds. (1994). An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 40. ISBN 0313274975.

- ^ "Lake Van" 1998.

- ^ a b Wong & Degens 1978.

- ^ Tomonaga, Brennwald & Kipfer 2011.

- ^ Sarı 2008.

- ^ a b c Toker et al. 2017, p. 166.

- ^ a b Toker et al. 2017, p. 167.

- ^ Kempe & Degens 1978.

- ^ Oswald 1906, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Landmann et al. 1996.

- ^ University of Bonn 2007.

- ^ "Recession continues in Turkey's largest lake". Bianet. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ^ Матвеев: Турция [что значительно ниже установленной позже корректной цифры в 161,2 метра] (in Russian)

- ^ Warren 2006.

- ^ Danulat & Kempe 1992.

- ^ Sarı 2006.

- ^ "New fish species found in Turkey's Lake Van". Hürriyet Daily News. 22 October 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Akkuş, Mustafa; Sarı, Mustafa; Ekmekçi, F. Güler; Yoğurtçuoğlu, Baran (16 March 2021). "The discovery of a microbialite-associated freshwater fish in the world's largest saline soda lake, Lake Van (Turkey)". Zoosystematics and Evolution. 97 (1): 181–189. doi:10.3897/zse.97.62120. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ^ Selçuk 1992

- ^ Kempe et al. 1991.

- ^ Cottrell 1960, p. 488.

- ^ Gibbens 2017.

- ^ Ancient castle studied... 2017.

- ^ Ebeling & Meissner 1997, p. 2.

- ^ a b Hewsen 1997, p. 9.

- ^ a b Mina 2015.

- ^ Van Gölü canavarı gerçek mi? 131 yıl önce Osmanlı gazetesinde manşet olmuş mynet. 22 April 2020.

- ^ Oktay 2007.

- ^ UNESCO n.d.

- ^ APA 2007.

- ^ "sosyalastirmalar.com geomorphology of Lake Ercek pdf" (PDF). Retrieved 3 March 2024.

Sources

- "Ancient castle studied in Lake Van", Hürriyet Daily News, 15 November 2017, retrieved 27 February 2018

- APA (27 July 2007), "Turkey, Iran agree on joint railway", Yeni Şafak, archived from the original on 7 October 2008

- Coskun, M.; Musaoğlu, N. (2004), "Investigation of Rainfall-Runoff Modelling of the Van Lake Catchment by Using Remote Sensing and GIS Integration" (PDF), Proceedings of the 20th Congress of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing, archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2004

- Cottrell, Leonard (1960), The Concise Encyclopædia of Archaeology

- Danulat, Eva; Kempe, Stephan (February 1992), "Nitrogenous waste excretion and accumulation of urea and ammonia in Chalcalburnus tarichi (Cyprinidae), endemic to the extremely alkaline Lake Van (Eastern Turkey)", Fish Physiology and Biochemistry, 9 (5–6): 377–386, Bibcode:1992FPBio...9..377D, doi:10.1007/BF02274218, PMID 24213814, S2CID 7471283

- Degens, E.T.; Wong, H.K.; Kempe, S.; Kurtman, F. (June 1984), "A geological study of Lake Van, eastern Turkey", International Journal of Earth Sciences, 73 (2), Springer: 701–734, Bibcode:1984GeoRu..73..701D, doi:10.1007/BF01824978, S2CID 128628465

- Ebeling, Erich; Meissner, Bruno (1997), Reallexikon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie [Lexicon of Assyriology and Near Eastern Archeology] (in German), Berlin: de Gruyter, p. 2, ISBN 978-3110148091

- Gibbens, Sarah (15 November 2017). "Ancient Ruins Discovered Under Lake in Turkey". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017.

- Hewsen, Robert H. (September 1997), "The Geography of Armenia", in Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.), The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, vol. I – The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century, New York: St. Martin's Press, pp. 1–17, ISBN 978-0-312-10169-5

- Kempe, S.; Degens, E.T. (1978), "Lake Van varve record: the past 10,420 years", in Degens, E.T.; Kurtman, F. (eds.), Geology of Lake Van, Ankara: MTA Press, pp. 56–63

- Kempe, S.; Kazmierczak, J.; Landmann, G.; Konuk, T.; Reimer, A.; Lipp, A. (14 February 1991), "Largest known microbialites discovered in Lake Van, Turkey", Nature, 349 (6310): 605–608, Bibcode:1991Natur.349..605K, doi:10.1038/349605a0, S2CID 4240438

- "Lake Van", The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 1998

- Landmann, Günter; Reimera, Andreas; Lemcke, Gerry; Kempe, Stephan (June 1996), "Dating Late Glacial abrupt climate changes in the 14,570 yr long continuous varve record of Lake Van, Turkey", Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 122 (1–4), Elsevier Science B.V.: 107–118, Bibcode:1996PPP...122..107L, doi:10.1016/0031-0182(95)00101-8

- Mina, Muhammed (19 December 2015), Türkiye'nin en büyük feribotu Van Gölü'nde deneme seferine çıktı [Turkey's Largest Ferry Begins Trial Voyage on Lake Van] (in Turkish), Hürriyet

- Oktay, Yüksel (8 May 2007). "On the Roads of Anatolia — Van". Los Angeles Chronicle. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- Oswald, Felix (1906), A Treatise on the Geology of Armenia

- Sarı, Mustafa (2006), Inci Kefalı Summary, Doğa Gözcüleri Derneği, archived from the original on 11 January 2008

- Sarı, Mustafa (2008), "Threatened fishes of the world: Chalcalburnus tarichi (Pallas 1811) (Cyprinidae) living in the highly alkaline Lake Van, Turkey", Environmental Biology of Fishes, 81 (1), Springer Netherlands: 21–23, doi:10.1007/s10641-006-9154-9, S2CID 36074817

- Toker, Mustafa; Sengör, Ali Mehmet Celal; Demirel Schluter, Filiz; Demirbağ, Emin; Çukur, Deniz; İmren, Caner; Niessen, Frank (May 2017), "The structural elements and tectonics of the Lake Van basin (Eastern Anatolia) from multi-channel seismic reflection profiles", Journal of African Earth Sciences, 129: 165–178, Bibcode:2017JAfES.129..165T, doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2017.01.002

- Tomonaga, Yama; Brennwald, Matthias S.; Kipfer, Rolf (2011), "Spatial distribution and flux of terrigenic He dissolved in the sediment pore water of Lake Van (Turkey)", Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 75 (10): 2848–2864, Bibcode:2011GeCoA..75.2848T, doi:10.1016/j.gca.2011.02.038

- UNESCO, Tentative World Heritage Sites

- University of Bonn (15 March 2007), Turkey's Lake Van Provides Precise Insights into Eurasia's Climate History, Science Daily

- Warren, J.K. (2006), Evaporites: Sediments, Resources and Hydrocarbons, Springer, ISBN 978-3-540-26011-0

- Wong, H.K.; Degens, E.T. (1978), "The bathymetry of Lake Van, eastern Turkey", Geology of Lake Van, Ankara: General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration, pp. 6–10