Wudang Mountains

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Hubei, China |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, vi |

| Reference | 705 |

| Inscription | 1994 (18th Session) |

| Coordinates | 32°24′03″N 111°00′14″E / 32.400833°N 111.003889°E |

| Wudang Mountains | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Wudang Mountains" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 武當山 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 武当山 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

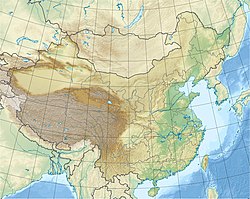

The Wudang Mountains (simplified Chinese: 武当山; traditional Chinese: 武當山; pinyin: Wǔdāng Shān) are a mountain range in the northwestern part of Hubei, China. They are home to a famous complex of Taoist temples and monasteries associated with the Lord of the North, Xuantian Shangdi. The Wudang Mountains are renowned for the practice of tai chi and Taoism as the Taoist counterpart to the Shaolin Monastery,[1] which is affiliated with Chan Buddhism. The Wudang Mountains are one of the "Four Sacred Mountains of Taoism" in China, an important destination for Taoist pilgrimages. The monasteries such as the Wudang Garden[1] were made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994 because of their religious significance and architectural achievement.[2]

Geography

[edit]On Chinese maps, the name "Wudangshan" (Chinese: 武当山) is applied both to the entire mountain range (which runs east-west along the southern edge of the Han River, crossing several county-level divisions of Shiyan), and to the group of peaks located within Wudangshan subdistrict of Danjiangkou, Shiyan. It is the latter specific area which is known as a Taoist center.[3]

Modern maps show the elevation of the highest of the peaks in the Wudang Shan "proper" as 1612 meters;[3][4] however, the entire Wudangshan range has somewhat higher elevations elsewhere.[3]

Some consider the Wudang Mountains to be a "branch" of the Daba Mountains range,[4] which is a major mountain system in western Hubei, Shaanxi, Chongqing and Sichuan.

History

[edit]For centuries, the mountains of Wudang have been known as an important center of Taoism, especially famous for its Taoist versions of martial arts or tai chi.[5]

The first sacred site—the Five Dragons Temple—was constructed at the behest of Emperor Taizong of Tang.[2] Further structures were added during the Song and Yuan dynasties, while the largest complex on the mountain was built during the Ming dynasty (14th–17th centuries) as the Yongle Emperor claimed to enjoy the protection of the god Beidi or Xuantian Shangdi.[2] During the Ming Dynasty, 9 palaces, 9 monasteries, 36 nunneries and 72 temples were located at the site.[2] Temples regularly had to be rebuilt, and not all survived; the oldest existing structures are the Golden Hall and the Ancient Bronze Shrine, made in 1307.[2] Other noted structures include Nanyang Palace (built in 1285–1310 and extended in 1312), the stone-walled Forbidden City of the Taihe Palace at the peak (built in 1419), and the Purple Cloud Temple (built in 1119–1126, rebuilt in 1413 and extended in 1803–1820).[2][6] Today, 53 ancient buildings still survive. [2]

On January 19, 2003, the 600-year-old Yuzhengong Palace at the Wudang Mountains burned down after accidentally being set on fire by an employee of a martial arts school.[7] A fire broke out in the hall, reducing the three rooms that covered 200 square meters to ashes. A gold-plated statue of Zhang Sanfeng, which was usually housed in Yuzhengong, was moved to another building just before the fire, and so escaped destruction in the inferno.[5]

-

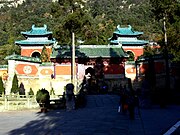

The Purple Cloud monastery at Wudang Mountains

-

The Gate of Yuan Wu at Wudang Mountains

-

Purple Heaven Palace

Association with martial arts

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Chinese martial arts (Wushu) |

|---|

|

At the first national martial arts tournament organized by the Central Guoshu Institute in 1928, participants were separated into practitioners of Shaolin and Wudang styles. Styles considered to belong to the latter group—called Wudangquan—are those with a strong element of Taoist neidan exercises. Typical examples of Wudangquan are tai chi, xingyiquan, Bajiquan and baguazhang. According to legend, tai chi was created by the Taoist hermit sage Zhang Sanfeng, who lived in the Wudang mountains.[8]

Wudangquan has been partly reformed to fit the PRC sport and health promotion program. The third biannual Traditional Wushu Festival was held in the Wudang Mountains from October 28 to November 2, 2008.[9]

See also

[edit]- Xuantian Shangdi

- Five Immortals Temple

- Golden Hall

- Purple Cloud Temple

- Silk reeling

- Daoyin

- Zhang Sanfeng

- Yang Luchan

- Wudang School

- Wudangquan

References

[edit]- ^ a b "武當集團" [Wudang Group]. www.wudanglife.com (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 7 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Ancient Building Complex in the Wudang Mountains". whc.unesco.org.

- ^ a b c Road Atlas of Hubei (湖北省公路里程地图册; Hubei Sheng Gonglu Licheng Dituce), published by 中国地图出版社 SinoMaps Press, 2007, ISBN 978-7-5031-4380-9. Page 11 (Shiyan City), and the map of the Wudangshan world heritage area, within the back cover.

- ^ a b Atlas of World Heritage: China. Long River Press. 1 January 2005. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-1-59265-060-6. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ^ a b Wang, Fang (May 11, 2004). "Pilgrimage to Wudang". Beijing Today. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- ^ Huadong, Guo (2013). Atlas of Remote Sensing for World Heritage: China. Springer. p. 126. ISBN 978-3-642-32823-7.

- ^ "China's world heritage sites over-exploited". China Daily. December 22, 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- ^ Henning, Stanley (1994). "Ignorance, Legend and Taijiquan". Journal of the Chen Style Taijiquan Research Association of Hawaii. 2 (3). Archived from the original on 2010-01-01. Retrieved 2013-11-13.

- ^ 李. Every year in the autumn a new festival is organized as part of the yearly festival calendar., 鹏翔 (April 18, 2008). "第三届世界传统武术节将在湖北十堰举行". 新华社稿件. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

Bibliography

[edit]- Pierre-Henry de Bruyn, Le Wudang Shan: Histoire des récits fondateurs, Paris, Les Indes savantes, 2010, 444 pp.

External links

[edit] Media related to Wudang Mountains at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wudang Mountains at Wikimedia Commons- UNESCO World Heritage Sites descriptions

- Wudang Mountain Kung Fu Academy (Founded by the government)

- International Wudang Federation (including training in Wudangshan) Archived 2016-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Wudang Global Federation