Church of Les Billettes, Paris

| Church of Les Billettes, Paris | |

|---|---|

Cloître et église des Billettes | |

The facade of Les Billettes | |

| |

| Location | 22 Rue des Archives, 75004 Paris |

| Country | France |

| Denomination | Lutheran |

| Website | eglise-billettes.epudf.org |

| Architecture | |

| Heritage designation | Monument historique |

| Designated | 1988 |

| Architect(s) | Jacques Hardouin-Mansart de Saganne |

The Church of Les Billettes is a Lutheran church located at 22 rue des Archives in the 4th arrondissement of Paris. Built as a Catholic church in the 18th century, it adjoins the 15th century cloister of the Abbey of the Hospitaliers of the Charity of Notre Dame, also known as the Billettes. The 15th century church was demolished, except for the cloister, and replaced by the new church In 1808, Under Napoleon I, it became a Protestant Lutheran church.

The church is built in the Neoclassiscal style, while the earlier adjoining cloister is Gothic. The name of the church refers to the monks in the old abbey, who were known as the "Freres Billettes". To identify their order they wore an emblem called a billette.

The most famous feature of the church is the cloister, adjoining the church, dating from the 15h century. It is the only medieval cloister in Paris surviving in its original state.[1]

History

[edit]The legend and the first church

[edit]Before the church was built, the site was occupied by an earlier chapel, built in 1295, known as "The Chapel of Miracles". According to the legend of the church, the site was originally occupied by the home of a Jewish merchant named Jonas. On Easter Sunday, April 2, 1290, Jonas had tried to profane Easter by piercing the host, the bread symbolizing the body of Christ, with a knife; the host bled the blood of Christ. He put it into boiling water, but it turned the water into blood. He threw it into the fire, but it flew away. The host was found outside some time later by a neighbor, and was preserved as a sacred object until the Revolution. Jonas was arrested and convicted of sacrilege, and was burned at the stake. His house was confiscated and demolished. The story was repeated in Medieval chronicles, and the site became a destination for pilgrims.[2] In 1299 the Chapel of Miracles was built on the same site to commemorate the event.[1] King Philippe IV of France invited the order of the Charity of Notre Dame, also known as the Billettes, to arrange services in the new church. The church continued to attract large numbers of pilgrims. It was rebuilt on a larger scale in 1405, and a cemetery and cloister were added in 1427.[3]

17th-19th century church

[edit]In 1633, the abbey and church were taken over by a new order, the Carmelites of the Observance of Rennes, also known as the Carmes-Billettes. In 1742 the Carmes-Billettes began construction of a larger church. They chose the architect Jacques Hardouin-Mansart de Sagonne (1711-1778), grandson of Jules Hardouin-Mansart, founder of the famed Mansard dynasty of architects. At that time Mansard de Sagonne was building the Cathédrale Saint-Louis de Versailles for King Louis XV at the Palace of Versailles. He designed a larger church for Les Billettes, which increased the number of worshippers from 960 to 1200. Construction of the new church lasted from 1754 until 1758. From the original medieval church only the cloister was preserved.

During the French Revolution, the church was closed and sold. The cloister was used as a workshop for carpenters, while the church was used to store salt. In 1808, the Emperor Napoleon authorized the city of Paris to buy the church, which was then transferred to the Consistory of the Lutheran Church, which was looking for a Paris home.[1]

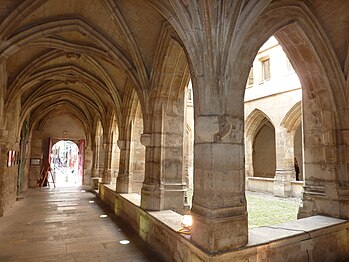

The cloister

[edit]THe cloister is the only surviving part of the earlier medieval Chapel of Miracles. It was built in 1427, and was restored to its original form in 1968. It is composed of four galleries of arcades, supported by octagonal columns. The traverses are covered with Gothic rib vaults formed by pointed arches, The keystones of the vaults are decorated with sculpture.[1]

-

Courtyard of the cloister

-

Interior of the cloister

-

Detail of the cloister

Exterior

[edit]The facade of the church is in the neoclassical style, rising up in two levels. The lower level has Doric pilasters around the portal, while the upper level has Corinthian style pilasters. The triangular pediment at the top of the facade is in a fragile condition and is protected by a tarpaulin, which hides the decoration.[4]

-

The cloister exterior

-

The facade and bell tower

-

The church at night

Interior

[edit]The interior of the church is in the neoclassical style. The choir is round, surrounded with pilasters in the Corinthian style|. It is topped with a circle of windows with white glass, with a dome above. The windows and pilasters continue along the upper walls of the church to the portal. There are two levels of balconies or tribunes along the sides in the nave, supported by ionic style pillars.[4] The church originally had only one level of balconies; the upper was added in 1824 by the Duchess of Orleans, who was an important patron of the church. Her loge had a separate concealed entrance, so she could come and go easily.[5]

In keeping with the doctrine of the Lutheran church, the decoration of the choir is extremely simple; only the most essential elements are present; an altar, candles, a crucifix, and a lectern. The altar and lectern are recent creations made by Philippe Keppelin in the 20th century.[4]

The organ of the church is found in the tribune at the end of the nave, over the portal. It is a modern instrument, made by the factor Mülheisen in 1982–1983.[4]

-

Dome of the choir

-

Tribunes of the nave

-

Upper window

-

The portal and the organ

Art and decoration

[edit]The decoration of the church is rather austere, following Lutheran tradition, but it does contain three notable paintings from the 17th century:

- The Good Samaritan and The Healing of the blind man of Jericho, both painted by Johann Carl Loth (1632-1698). They feature massive figures, dramatic illumination and warm colors, in the style of Mannerism.

- Christ on the Cross by Lubin Baugin (1612-1663), showing the body of Christ filling the canvas, delicately illuminated and perfectly poised, against a background of turbulence and darknness[5]

Notes and citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris" (2017), pp. 58-59

- ^ [1] History of church on website of Protestant Churches of France (in French)

- ^ Cachau, Philippe, L’Eglise Des Carrmes-Billettes de Paris; Une Eglise d'apres Jacques Harouin-Mansart de Sagonne (1744-1758)

- ^ a b c d [2] Site on history and art of the church (in French)

- ^ a b Dumoulin, "Églises de Paris" (2017), p. 59

Bibliography (in French)

[edit]- Dumoulin, Aline; Ardisson, Alexandra; Maingard, Jérôme; Antonello, Murielle; Églises de Paris (2010), Éditions Massin, Issy-Les-Moulineaux, ISBN 978-2-7072-0683-1 (in French)

- Hillairet, Jacques; Connaissance du Vieux Paris; (2017); Éditions Payot-Rivages, Paris (in French). ISBN 978-2-2289-1911-1 (In French)

External links

[edit]- Website of the church (in French)

- History of the church on the website of Protesant Churches of France (in French)

- Article in French Wikipedia

- Site on history and art of the church (in French)

- Detailed article by Philippe Cachau on the history of the church (in French)