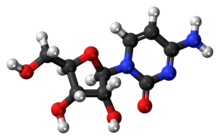

Cytidine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

4-Amino-1-[(2R,3R,4S,5R)-3,4-dihydroxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)oxolan-2-yl]pyrimidin-2(1H)-one | |

| Other names

4-Amino-1-β-D-ribofuranosyl-2(1H)-pyrimidinone[1]

4-Amino-1-[3,4-dihydroxy-5-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydrofuran-2-yl]pyrimidin-2-one | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.555 |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Cytidine |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C9H13N3O5 | |

| Molar mass | 243.217 |

| Appearance | white, crystalline powder[2] |

| Melting point | 230 °C (decomposes)[1] |

| -123.7·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Cytidine (symbol C or Cyd) is a nucleoside molecule that is formed when cytosine is attached to a ribose ring (also known as a ribofuranose) via a β-N1-glycosidic bond. Cytidine is a component of RNA.

If cytosine is attached to a deoxyribose ring, it is known as a deoxycytidine.

Properties

Cytidine is a white, crystalline powder.[2] It is very soluble in water, but only slightly soluble in ethanol.[1]

Dietary sources

Dietary sources of cytidine include foods with high RNA (ribonucleic acid) content,[3] such as organ meats, brewer's yeast, as well as pyrimidine-rich foods such as beer. During digestion, RNA-rich foods are broken-down into ribosyl pyrimidines (cytidine and uridine), which are absorbed intact.[3] In humans, dietary cytidine is converted into uridine,[4] which is probably the compound behind cytidine's metabolic effects.

Cytidine analogues

There are a variety of cytidine analogues with potentially useful pharmacology. For example, KP-1461 is an anti-HIV agent that works as a viral mutagen,[5] and zebularine exists in E. coli and is being examined for chemotherapy. Low doses of azacitidine and its analog decitabine have shown results against cancer through epigenetic demethylation.[6]

Biological actions

In addition to its role as a pyrimidine component of RNA, cytidine has been found to control neuronal-glial glutamate cycling, with supplementation decreasing midfrontal/cerebral glutamate/glutamine levels.[7] As such, cytidine has generated interest as a potential glutamatergic antidepressant drug.[7]

References

- ^ a b c William M. Haynes (2016). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (97th ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. p. 3–140. ISBN 978-1-4987-5429-3.

- ^ a b Robert A. Lewis, Michael D. Larrañaga, Richard J. Lewis Sr. (2016). Hawley's Condensed Chemical Dictionary (16th ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 688. ISBN 978-1-118-13515-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Jonas DA; Elmadfa I; Engel KH; et al. (2001). "Safety considerations of DNA in food". Ann Nutr Metab. 45 (6): 235–54. doi:10.1159/000046734. PMID 11786646.

- ^ Wurtman RJ, Regan M, Ulus I, Yu L (Oct 2000). "Effect of oral CDP-choline on plasma choline and uridine levels in humans". Biochem. Pharmacol. 60 (7): 989–92. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(00)00436-6. PMID 10974208.

- ^ John S. James. "New Kind of Antiretroviral, KP-1461". AIDS Treatment News. Archived from the original on 2019-03-30. Retrieved 2012-03-23.

- ^ "Scientists reprogram cancer cells with low doses of epigenetic drugs". Medical XPress. March 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Machado-Vieira, Rodrigo; Salvadore, Giacomo; DiazGranados, Nancy; Ibrahim, Lobna; Latov, David; Wheeler-Castillo, Cristina; Baumann, Jacqueline; Henter, Ioline D.; Zarate, Carlos A. (2010). "New Therapeutic Targets for Mood Disorders". The Scientific World Journal. 10: 713–726. doi:10.1100/tsw.2010.65. ISSN 1537-744X. PMC 3035047. PMID 20419280.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)