Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi

| Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi | |

|---|---|

| |

| In Hawaii | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Cactaceae |

| Subfamily: | Cactoideae |

| Genus: | Trichocereus |

| Species: | |

| Variety: | T. m. var. pachanoi

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi (Britton and Rose) Albesiano & R.Kiesling 2012

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi (synonyms including Trichocereus pachanoi and Echinopsis pachanoi) is a fast-growing columnar cactus found in the Andes at 2,000–3,000 m (6,600–9,800 ft) in altitude.[3][4] It is one of a number of kinds of cacti known as San Pedro cactus. It is native to Ecuador, Peru and Colombia,[2] but also found in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile and Venezuela and cultivated in other parts of the world.[5][6] Uses for it include traditional medicine and traditional veterinary medicine, and it is widely grown as an ornamental cactus. It has been used for healing and religious divination in the Andes Mountains region for over 3,000 years.[7]

Description

[edit]Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi is native to Ecuador, Peru and Colombia. Its stems are light to dark green, sometimes glaucous, with a diameter of 6–15 cm (2.4–5.9 in) and usually 6–8 ribs. The whitish areoles may produce up to seven yellow to brown spines, each up to 2 cm (0.8 in) long although typically shorter in cultivated varieties, sometimes being mostly spineless.[4] The number and length of the spines is a feature that distinguishes T. macrogonus var. pachanoi from var. macrogonus, which may have up to 20 spines with three or four longer and more robust central ones up to 5 cm (2.0 in) long.[8] The areoles are spaced evenly along the ribs, approximately 2 cm (0.8 in) apart.[5] Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi is normally 3–6 m (10–20 ft) tall and has multiple branches, usually extending from the base but will emerge around broken branches.[4] The tallest recorded specimen was 12.2 metres (40 ft) tall.[5] White flowers are produced at the end of the stems; they open at night and last for about two days. Large numbers can be produced by well established cacti and may open new flowers over a period of weeks. The flowers are large, around 19–24 cm (7.5–9.4 in) long with a diameter of up to 20 cm (7.9 in) and are highly fragrant. There are black hairs along the length of the thick base leading to the flower. Oblong dark green fruits are produced after fertilization, about 3 cm (1.2 in) across and 5–6 cm (2.0–2.4 in) long,[4] eventually bursting open to reveal a white flesh filled with small seeds.

Taxonomy

[edit]Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi was first described as the species Trichocereus pachanoi by Britton and Rose in 1920. As a species, it has also been placed in the genera Cereus and Echinopsis. It was reduced to a variety of Trichocereus macrogonus in 2012. It can be distinguished from T. macrogonus var. macrogonus by the smaller number of spines per areole, and usually being somewhat shorter with more slender stems.[8]

Traditional uses

[edit]

Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi is known by many names throughout South America such as achuma, huachuma, wachuma, aguacolla, hahuacollay, lapituq, tsuná, San Pedro or giganton.[9][10] It has a long history of being used in Andean traditional medicine. Archaeological studies have found evidence of use going back two thousand years, to Moche culture,[11] Nazca culture,[12] and Chavín culture. Although Roman Catholic church authorities[who?] after the Spanish conquest attempted to suppress its use,[13] this failed, as shown by the Christian element in the common name "San Pedro cactus" – Saint Peter cactus. The name is attributed[by whom?] to the belief that just as St Peter holds the keys to heaven, the effects of the cactus allow users "to reach heaven while still on earth."[14] In 2022, the Peruvian Ministry of Culture declared the traditional use of San Pedro cactus in northern Peru as cultural heritage.[15]

Alkaloids

[edit]

Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi contains a number of alkaloids (especially cactus alkaloids), including the well-studied chemical mescaline (from 0.053% up to 4.7% of dry cactus weight),[16] and also 3,4-dimethoxyphenethylamine, 3-Methoxytyramine, 4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenethylamine, anhalonidine, anhalinine, hordenine, and tyramine.[17]

Mescaline is a psychedelic drug and entheogen, which is also found in some species of the genus Echinopsis (e.g. Echinopsis lageniformis, Echinopsis scopulicola and Echinopsis tacaquirensis) and the species Lophophora williamsii (peyote).[18] Mescaline induces a psychedelic state comparable to those produced by LSD and psilocybin, but with unique characteristics.[19] According to a research project in the Netherlands, ceremonial San Pedro use seems to be characterized by relatively strong spiritual experiences, and low incidence of challenging experiences.[20]

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the highest concentration of active substances is found in the layer of green photosynthetic tissue just beneath the skin.[5][21][22] Mescaline is not evenly distributed within single specimens of San Pedro cactus.[23]

Cultivation

[edit]

Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi in USDA hardiness zones 8b to 10.[24] The range of minimum temperatures in which it is known to grow is between -9.4 °C and 10 °C.[25] Because it grows naturally in the Andes at high altitude and with high rainfall, it can withstand temperatures far below that of many other cacti. It requires fertile, free-draining soil. A good soil mix includes an inorganic lightweight substrate such as pumice or perlite. Plants grow up to 30 cm per year.[5][unreliable source?][26][27] They are susceptible to fungal diseases if over-watered, but are not nearly as sensitive as many other cacti, especially in warm weather when they are in their growth phase. They can be sunburned and display a yellowing chlorotic reaction to overexposure to sunlight.[citation needed][27]

In winter, plants will etiolate, or become thin, due to lower levels of light. This may be problematic if the etiolated zone is not sufficiently strong to support future growth as the cactus may break in strong winds.[citation needed]

Propagation from cuttings

[edit]Like many other plants, Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi can be propagated from cuttings. The result is a genetic clone of the parent plant.[28] It is therefore a popular method of propagating highly prized cultivars, sometimes by grafting small cuttings onto fast-growing cultivars like the Predominant Cultivar (PC). Some names of cultivars that are highly prized by cactus collectors are Ogunbodede, Vilcabamba A, and Yowie.[29]

A cactus column can be also laid on its side on the ground (like a log), and eventually roots will sprout from it and grow into the ground. After time, sprouts will form and cactus columns will grow upward out of it along its length.[28]

From seed

[edit]Like a lot of its relatives, Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi is easily grown from seed, often by means of a so-called "Takeaway Tek".[30][31][32] This term refers to the practice of the sowing of Trichocereus (and sometimes other types of cactus) seed into plastic containers, such as those many food takeaways are delivered in. This creates a semi-controlled humidity environment chamber for six months to a year, in which the seed may germinate and then grow relatively unbothered by environmental contamination.[33] To accelerate the growth of seedlings, they can be grafted on Pereskiopsis.[34][35]

Legality

[edit]In most countries, it is legal to cultivate Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi. In countries where possession of mescaline and related compounds is illegal and highly penalized, cultivation for the purposes of consumption is most likely illegal and also highly penalized. This is the case in the United States, Australia, Canada, Sweden, Germany, and New Zealand, where it is currently legal to cultivate the San Pedro cactus for gardening and ornamental purposes, but not for consumption.[citation needed]

Gallery

[edit]-

Seeds

-

Three-week-old seedling

-

Five-month-old seedling

-

The fruit after bursting open, revealing the seeds in a sweet flesh.

-

Ripe fruits

See also

[edit]- Ayahuasca

- Chavín de Huántar

- Cimora

- El Paraíso, Peru

- Guitarrero Cave

- List of psychoactive plants

- Psychedelic microdosing

- Stela of the cactus bearer

References

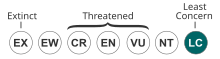

[edit]- ^ Ostalaza, C., Cáceres, F. & Roque, J. 2017. Echinopsis pachanoi (amended version of 2013 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017: e.T152445A121474583. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T152445A121474583.en. Downloaded on 11 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi (Britton & Rose) Albesiano & R.Kiesling". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ Rätsch, Christian (2002). Enzyklopädie der psychoaktiven Pflanzen. Botanik, Ethnopharmakologie und Anwendungen. Aarau: AT-Verlag. p. 15. ISBN 978-3-85502-570-1.

- ^ a b c d Anderson 2001, p. 276.

- ^ a b c d e Visionary Cactus Guide, Erowid.org, retrieved 2012-10-24

- ^ Mchem, Benjamin Bury (2021-08-02). "Could Synthetic Mescaline Protect Declining Peyote Populations?". Chacruna. Archived from the original on 2021-08-02. Retrieved 2021-09-21.

- ^ Bigwood, Jeremy; Stafford, Peter J. (1992). Psychedelics encyclopedia. Berkeley, CA: Ronin Pub. pp. 118–9. ISBN 978-0-914171-51-5.

- ^ a b Albesiano, Sofía (2012), "A New Taxonomic Treatment of the Genus Trichocereus (Cactaceae) in Chile", Haseltonia, 18: 116–139, doi:10.2985/026.018.0114, S2CID 84425131

- ^ Richard Evans Schultes; Albert Hofmann. Plantas de los dioses. Origenes del uso de los alucinogenos (in Spanish).

- ^ "San Pedro: Basic Info". ICEERS. 2019-09-20. Archived from the original on 2020-03-18. Retrieved 2022-01-01.

- ^ Bussmann RW, Sharon D (2006). "Traditional medicinal plant use in Northern Peru: tracking two thousand years of healing culture". J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2 (1): 47. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-2-47. PMC 1637095. PMID 17090303.

- ^ Socha, Dagmara M.; Sykutera, Marzena; Orefici, Giuseppe (2022-12-01). "Use of psychoactive and stimulant plants on the south coast of Peru from the Early Intermediate to Late Intermediate Period". Journal of Archaeological Science. 148: 105688. Bibcode:2022JArSc.148j5688S. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2022.105688. ISSN 0305-4403. S2CID 252954052.

- ^ Larco, Laura (2008). "Archivo Arquidiocesano de Trujillo Sección Idolatrías. (Años 1768-1771)". Más allá de los encantos – Documentos sobre extirpación de idolatrías, Trujillo. Travaux de l'IFEA. Lima: IFEA Instituto Francés de Estudios Andinos, Fondo Editorial de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. pp. 67–87. ISBN 9782821844537. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Edward F. (2001). The Cactus Family. Pentland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-498-5. pp. 45–49.

- ^ "Declaran Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación a los conocimientos, saberes y usos del cactus San Pedro". elperuano.pe (in Spanish). 2022-11-17. Retrieved 2022-12-10.

- ^ Ogunbodede, O.; McCombs, D.; Trout, K.; Daley, P.; Terry, M. (15 September 2010). "New mescaline concentrations from 14 taxa/cultivars of Echinopsis spp. (Cactaceae) ("San Pedro") and their relevance to shamanic practice" (PDF). Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 131 (2): 356–362. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.07.021. PMID 20637277. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Crosby, D.M.; McLaughlin, J.L. (Dec 1973). "Cactus Alkaloids. XIX Crystallization of Mescaline HCl and 3-Methoxytyramine HCl from Trichocereus panchanoi" (PDF). Lloydia and the Journal of Natural Products. 36 (4): 416–418. PMID 4773270. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ Anderson 2001, pp. 44–49.

- ^ Bender, Eric (2022-09-28). "Finding medical value in mescaline". Nature. 609 (7929): S90 – S91. Bibcode:2022Natur.609S..90B. doi:10.1038/d41586-022-02873-8. PMID 36171368. S2CID 252548055.

- ^ Bohn, Arne; Kiggen, Michiel H. H.; Uthaug, Malin V.; van Oorsouw, Kim I. M.; Ramaekers, Johannes G.; van Schie, Hein T. (2022-12-05). "Altered States of Consciousness During Ceremonial San Pedro Use". The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 33 (4): 309–331. doi:10.1080/10508619.2022.2139502. hdl:2066/285968. ISSN 1050-8619.

- ^ Lin, Jiaman; Yang, Shuo; Ji, Jiaojiao; Xiang, Ping; Wu, Lina; Chen, Hang (2023). "Natural or artificial: An example of topographic spatial distribution analysis of mescaline in cactus plants by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry imaging". Frontiers in Plant Science. 14. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1066595. ISSN 1664-462X. PMC 9950628. PMID 36844095.

- ^ "Mescaline in Trichocereus". The Mescaline Garden. Archived from the original on 2024-08-08. Retrieved 2024-08-30.

- ^ Van Der Sypt, Frederick (2022-04-03). "Validation and exploratory application of a simple, rapid and economical procedure (MESQ) for the quantification of mescaline in fresh cactus tissue and aqueous cactus extracts". PhytoChem & BioSub Journal. doi:10.5281/zenodo.6409376.

- ^ "San Pedro Cactus (Echinopsis pachanoi)". Desert-tropicals.com. Archived from the original on 2011-10-21. Retrieved 2008-02-23.

- ^ "Echinopsis pachanoi (San Pedro Cactus)". Worldofsucculents.com. 9 June 2018.

- ^ Antosh, Gary (2021-07-06). "Growing San Pedro Cactus: How To Care For Trichocereus Pachanoi". Plant Care Today. Retrieved 2023-01-21.

- ^ a b "Trichocereus pachanoi". www.llifle.com. Retrieved 2024-08-30.

- ^ a b "What if the cut end doesn't dry properly and starts to mold" (PDF). Sacredcactus.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2012-02-07.

- ^ "Trichocereus 'Yowie' (Echinopsis)". Trichocereus.net. 2015-12-27. Retrieved 2024-09-11.

- ^ "Grow Cacti from Seed - Enhanced Takeaway Tek". Arkhamsbotanical.com. Archived from the original on 2019-03-29. Retrieved 2018-09-21.

- ^ "How to Grow Trichocereus Cacti from Seed". Dissidentreality.com. 2018-07-15. Archived from the original on 2019-08-08. Retrieved 2018-09-21.

- ^ "Takeaway Tek (How to germinate cacti seeds)". Herbalistics.com. 2015-07-07.

- ^ "Coke bottle tek: A terrarium technique". Entheogenesis Australis. Retrieved 2023-07-01.

- ^ Herbalistics (2015-07-08). "Grafting cacti to Pereskiopsis spathulata". Herbalistics. Retrieved 2024-06-07.

- ^ "Pereskiopsis – Trout's Notes". sacredcacti.com. Retrieved 2024-06-07.

Further reading

[edit]- Jay, Mike (2019). Mescaline: A Global History of the First Psychedelic. Yale University Press.

- Pollan, Michael (2021). This Is Your Mind on Plants. Penguin Press.

- Sharon, Douglas (2000). Shamanism & the Sacred Cactus: Ethnoarchaeological Evidence for San Pedro Use in Northern Peru. San Diego Museum of Man.

External links

[edit]- Cactus Culture Volume 1: Trichocereus by Patrick Noll

- Collective Statement from the Curanderos and Curanderas of North Peru on the State of Conservation of the San Pedro Cactus, their Traditional Knowledge, and the Use of Wild San Pedro by Foreigners by Curanderos and Curanderas of North Peru and Allies

- San Pedro: Basic Info – International Center for Ethnobotanical Education, Research, and Service (ICEERS)

- Psychoactive Cacti vault – Erowid