Hill figure

A hill figure is a large visual representation created by cutting into a steep hillside and revealing the underlying geology. It is a type of geoglyph usually designed to be seen from afar rather than above. In some cases trenches are dug and rubble made from material brighter than the natural bedrock is placed into them. The new material is often chalk, a soft and white form of limestone, leading to the alternative name of chalk figure for this form of art.[citation needed]

Hill figures cut in grass are a phenomenon especially seen in England, where examples include the Cerne Abbas Giant, the Uffington White Horse, and the Long Man of Wilmington, as well as the "lost" carvings at Cambridge, Oxford and Plymouth Hoe. From the 18th century onwards, many further ones were added. Many figures long thought to be ancient have been found to be relatively recent when subjected to modern archaeological scrutiny, at least in their current form. Only the Uffington White Horse appears to retain a prehistoric shape, while the Cerne Abbas Giant may be prehistoric, Romano-British, or Early Modern. Nevertheless, these figures, and their possible lost companions, have been iconic in the English people's conception of their past.[citation needed]

In England there are at least fifty landscape figures, the majority of which are in the south.[1]

History

[edit]The creation of hill figures has been practised since prehistory and can include human and animal forms. Cutting of horses is common, as well as more abstract symbols and, in the modern era, advertising brands.[citation needed]

The reasons for the creation for the figures are varied and obscure. The Uffington Horse probably held political significance, since the figure dominates the valley below. It probably dates to the British Iron Age since coins have been found exhibiting the symbol. The Cerne Abbas Giant might have been a work of political satire likely of the Early Modern period.[2] Wiltshire is a county with a large number of White Horses; 14 have been recorded.[3] The figures are usually created by the cutting away of the top layer of relatively poor soil on suitable hillsides. This exposes the white chalk beneath, which contrasts well with the short green hill grass, and the image is clearly visible for a considerable distance. Although most of the figures are of great age, many are relatively new. Devizes in Wiltshire created a large white horse for the 2000 Millennium celebrations and in October 2009 celebrated this with an aerial photo of volunteers making the figure 10 for an aerial photo.[4]

Figures must be maintained to remain visible, and local people often work regularly to restore or maintain a local landmark, though two cuttings of military badges at Sutton Mandeville, Wiltshire, are becoming lost. A lost map of Australia at Compton Chamberlayne, Wiltshire, was restored in 2018.[5]

Similar pictures exist elsewhere in the world, notably the far larger Nazca Lines in Peru, which are on flat land but visible from hills in the area. However, these were made in desert terrain rather than on grassy hillsides, so have not become overgrown and thus have survived much longer without maintenance. The Nazca Lines were formed by removing loose stones from the lines to expose the whiteish underlying soil, which is not itself dug.[citation needed]

Terminology

[edit]Geoglyph is the usual term for structures carved into or otherwise made from rock formations.

In 1949, Morris Marples "half-humorously" coined the words "leucippotomy for the cutting of white horses and gigantotomy for the cutting of giants on rare occasions".[6][7][8] Though neither word appears in the Oxford English Dictionary, the terms occasionally appear in print.[9]

Construction and maintenance

[edit]Until recently, three methods were used to construct white hill figures.[citation needed]

- The stripping method: where the soil is thin, the turf or soil is stripped away to expose the chalk underneath. This produces quick results but the figure needs regular maintenance, as it would soon become overgrown. This was a practice for hill figures but not as much for horses. The Laverstock Panda at Laverstock near Salisbury, Wiltshire was constructed this way in 1968 and is now lost. Traces of figures of this type are not usually found after the figure is overgrown.[citation needed]

- The covering method: rocks are placed on top of the turf. This method is normally used when there is no underlying chalk, the chalk is deep or tools are not available. The maintenance for these figures is very high. There are several examples, such as the Woolbury White Horse in Hampshire. This method leaves no trace of the figure's existence when overgrown, as is the case of the lost Fovant Badges in Wiltshire.[citation needed]

- The trenching method, which is by far the most common method of hill figure construction. The underlying chalk where some white horses are constructed is not near the surface, so a trench is dug and chalk from another site is used to fill it. The Uffington White Horse in Oxfordshire is the prime example of this method. This method is invasive in the hillside and allows traces of the figure to be seen even when the figure has been overgrown for many years, an example being the original Devizes White Horse, cut in 1845 and lost sometime in the mid 20th century, but rediscovered when traces reappeared.[citation needed]

The biggest threat to white horses and other hill figures is natural vegetation covering the figures. In the case of chalk figures, natural vegetation encroaches from the edges and can grow on soil washed onto the figure by rain. Water erosion can also be a problem on steep or gentle slopes, because rain can wash the chalk off the horse, or soil onto the horse. Larger horses are more susceptible to this. If chalk is washed off the horse, the horse gradually creeps down the slope; or if soil is washed onto the horse, it collects onto the lower edges and the horse gradually climbs up the slope. A solution is to provide drainage, either using run-off drains, as at Uffington White Horse, or a french ditch.[citation needed]

Since hill figures must be maintained by the removal of regrown turf, only those that motivate the local populace to look after them survive. Surviving ancient figures all have an associated fair or ceremony that involves maintaining them.[citation needed]

Unmaintained figures gradually fade away.[10] Firle Corn at Firle Beacon, Sussex could be a lost figure. Its existence is suggested by infrared photography. If it is a lost figure, its age is uncertain, and unlikely prehistoric in origin, as only one figure in the UK has been shown to be of this age, the Uffington White Horse.[citation needed]

Human figures

[edit]UK

[edit]While presumed to be of prehistoric origin, surviving examples may have been created only within the last four hundred years.[11] Of these giants only two survive: one near the village of Cerne Abbas, to the north of Dorchester, in Dorset and one at Wilmington, Long Man civil parish in the Wealden District of East Sussex. Examples located at Oxford, Cambridge, and on Plymouth Hoe can no longer be seen with the naked eye.[11][12][13]

The Osmington White Horse carries a rider (King George III) but is not considered an example of gigantotomy due to the name of the figure referring to the horse.[citation needed]

Cerne Abbas Giant

[edit]The Cerne Abbas Giant, also referred to as the "Rude Man" or the "Rude Giant", is a hill figure of a giant naked man 180 ft (55 m) high, 167 ft (51 m) wide.[2] The figure is carved into the side of a steep hill, and is best viewed from the opposite side of the valley or from the air. The carving is formed by a trench 12 in (30 cm) wide,[2] and about the same depth, which has been cut through grass and earth into the underlying chalk. In his right hand the giant holds a knobbled club 120 ft (37 m) in length.[2]

Its history cannot be traced back further than the late 17th century, making an origin during the Celtic, Roman or even Early Medieval periods difficult to prove. Above and to the right of the Giant's head is an earthwork known as the "Trendle", or "Frying Pan". Medieval writings refer to this location as "Trendle Hill", but make no mention of the giant, leading to the conclusion that it was probably only carved about 400 years ago. In contrast, the Uffington White Horse – an unquestionably prehistoric hill figure on the Berkshire Downs – was noticed and recorded by medieval authors.[2][14] In 2021, a sediment analysis by the National Trust indicated an origin in the date range of 700 CE to 1100 CE, surprising historians who did not expect it to be medieval.[15]

In 2008, overgrowth forced a re-chalking of the giant,[16] with 17 tonnes of new chalk being poured in and tamped down by hand.[17]

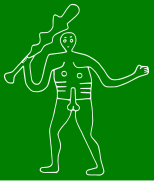

Long Man of Wilmington

[edit]

The Long Man of Wilmington is located on one of the steep slopes of Windover Hill, six miles (9.7 km) northwest of Eastbourne. The figure is 227 feet (69 m) tall and designed to look in proportion when viewed from below, and is shown holding two staves. The earliest record was made by the surveyor John Rowley in the year 1710. This drawing suggests that the original figure was a shadow or indentation in the grass, rather than the solid outline of a human figure. The staves were not depicted as a rake and scythe as was once thought, and the head was a helmet shape. Sir William Borrow's drawing of 1766 shows the figure holding a rake and a scythe, both shorter than the staves.[18]

Before 1874, the Long Man's outline was only visible in certain light conditions as a different shade in the hillside grass, or after a light fall of snow. In that year an antiquarian marked out the outline with yellow bricks, later cemented together. It has been claimed that the 'restoration' process distorted the position of the feet, an assertion backed up by several who had been familiar with the figure before 1874, and also by later resistivity surveys.[19] It has also been suggested that it removed the Long Man's genitalia, though there is no historical or archaeological evidence which supports that claim.[18][20] A wide range of dates of origin have been proposed for the Long Man, but more recent archaeological work done by the University of Reading suggests that the figure dates from the 16th or 17th century AD.[21]

Plymouth Hoe giants

[edit]Until the early 17th century large outline images of the two giants, perhaps Gog and Magog (or Goemagot and Corineus) had for a long time been cut into the turf of Plymouth Hoe exposing the white limestone beneath.[22] An early and explicit reference was made to them by Richard Carew in 1602.[23] At one time these figures were periodically re-cut and cleaned but no trace of them remains today.[22][24]

Firle Corn

[edit]Firle Corn in Firle, Sussex is a nearly-lost hill figure which can be seen with the aid of infrared photography. Now looking more like a small ear of corn or a strange weapon than a human figure, there is a legend suggesting that a giant called Gill was once cut on this same hill and that he was considered an adversary of the Long Man of Wilmington not far away.[25] According to one story, the giant on Firle Beacon threw his hammer at the Wilmington giant and killed him, and that the figure on the hillside marks the place where his body fell.[26]

Homer Simpson

[edit]As a publicity stunt for the opening of The Simpsons Movie on 16 July 2007, a giant Homer Simpson brandishing a doughnut was outlined in water-based biodegradable paint to the left of the Cerne Abbas Giant. This act angered local neopagans, who pledged to perform "rain magic" to wash the figure away.[27][28]

Other countries

[edit]Horse figures

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2024) |

There are 16 known white horse hill figures in the UK, or 17 including the painted one at Cleadon Hills.[29]

List of UK figures

[edit]Current figures

[edit]| Name | County | Cutting date |

|---|---|---|

| Uffington White Horse | Oxfordshire | 1000 BC |

| Westbury White Horse | Wiltshire | 1600s |

| Cherhill White Horse | Wiltshire | 1780 |

| Mormond White Horse | Aberdeenshire | 1790s |

| Marlborough White Horse | Wiltshire | 1804 |

| Osmington White Horse | Dorset | 1808 |

| Alton Barnes White Horse | Wiltshire | 1812 |

| Hackpen White Horse | Wiltshire | 1838 |

| Woolbury White Horse | Hampshire | Before 1846 |

| Kilburn White Horse | North Yorkshire | 1857 |

| Broad Town White Horse | Wiltshire | 1864 |

| Cleadon White Horse | South Tyneside | Before 1887 |

| Litlington White Horse | East Sussex | 1924 |

| Pewsey White Horse | Wiltshire | 1937 |

| Devizes White Horse | Wiltshire | 1999 |

| Heeley White Horse | South Yorkshire | 2000 |

| Folkestone White Horse | Kent | 2003 |

| Lutterworth white horses | Leicestershire | 2012 |

| Beverley Racecourse white horses | East Riding | 2010s |

| Black Horse of Bush Howe | Cumbria | ? (may be a natural figure) |

Lost figures

[edit]| Name | County | Cut | Lost | Replaced by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Westbury White Horse | Wiltshire | 878? | Before 1778 | New Westbury White Horse |

| The Giant Ghyst | Bristol | Before 1480[30] | ||

| Plymouth Hoe Gogmagog | Devon | Before 1486[31] | Late 1660s | – |

| Wandlebury Hill Gogmagog | Cambridgeshire | Before 1605 | Around 1730 | – |

| Old Pewsey White Horse | Wiltshire | 1785 | 1940 | New Pewsey White Horse |

| Pitstone Hill White Horse | Buckinghamshire | 1809? | Before 1990 | – |

| Old Litlington White Horse | Sussex | 1838 | 1924 | New Litlington White Horse |

| Old Devizes White Horse | Wiltshire | 1845 | Before 1999 | New Devizes White Horse |

| Hackpen White Horse | Wiltshire | 1868? | Before 1990 | – |

| Hindhead White Horse | Surrey | Before 1913 | 1939 | – |

| Red Horse of Tysoe | Warwickshire | Before 1607 | Remains lost in 1964 | - |

| Red Horse of Tysoe "IV" | Warwickshire | 1800 | 1910 | – |

| Rockley White Horse | Wiltshire | Discovered 1948 | After 1950, before 1990 | – |

| Tan Hill White Horse/Donkey | Wiltshire | Before 1975 | After 1975, before 1990 | – |

| Mossley White Horse (aka Luzley White Horse) | Greater Manchester | 1981[32] | After 1994, before 1999 | – |

| Folkestone White Horse mock-up | Kent | 1999 | 1999 | Folkestone White Horse |

| Laverstock Panda | Wiltshire | 1969 | 1984 | – |

| Pont Abraham Tea Pot and Cup | Wales | 1992 | 2009 | – |

Possible figures

[edit]| Name | County | Discovery date | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whittlesford White Horse | Cambridge | 2004 | A crop mark resembling a horse discovered 2004, possibly hinting a previous horse was cut here. |

| Liddington White Horse | Wiltshire | 2000s | Plans for this white horse (including designs) occurred in the 2000s, but the project never happened. |

| Red Horse of Tysoe "VI" | Warwickshire | 2010s | A forthcoming recutting of the Red Horse of Tysoe at the Vale of the Red Horse. |

List of international figures

[edit]| Name | Location | Cut | Lost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bloemfontein White Horse | Bloemfontein, South Africa | Before 1932 | N/A |

| Cockington Green white horse | Cockington Green, Canberra, Australia | 20th or 21st century | N/A |

| Georgia white horse | Georgia, United States | 20th or 21st century | N/A |

| Juárez White Horse | Ciudad Juárez, Mexico | Unknown | N/A |

| Riff Country horse | Iourdanan, Morocco | Unknown | Unknown |

| Spis Castle Celtic Horse | Žehra, Slovakia | 2000s | N/A |

| Tunis Horses | Tunis, Tunisia | Unknown | N/A |

| Waimate White [33] | Waimate, New Zealand | 1968 | N/A |

The horses in Cockington Green, Georgia and Juárez are all based on the style of or direct copies of the Uffington White Horse.[citation needed]

Other figures

[edit]UK

[edit]- Near Battle of Britain Memorial, Capel-le-Ferne, Kent (1993)[citation needed]

- Bulford Kiwi, Sling Camp (1919)

- Compton Chamberlayne Australia map, Wiltshire (1916)[10]

- Fovant badges, Wiltshire (1916-)

- Lenham Cross, Kent (1922)

- Shoreham, Kent memorial cross, Kent (1920)[citation needed]

- Sutton Mandeville military badges, Wiltshire (1916, photographed, to be lost soon

when?)[citation needed]

when?)[citation needed] - Whipsnade white lion, Bedfordshire (1931)

- Whitehawk hawk, Sussex (2001)[citation needed]

- Whiteleaf Cross, Monks Risborough, Buckinghamshire (earliest ref. 1742)

- Wye Crown, Kent (1902)

- Mormond White Stag, on the other side of the hill from the Mormond Horse.[34]

Influence on other art forms

[edit]The white horses of Wiltshire, of which there are currently nine, have inspired other sculptures in the county. Julive Livsey's sculpture White Horse Pacified (1987) in Shaw, Swindon was inspired by the white horses.[35]

In 2010, Charlotte Moreton created the steel sculpture White Horse for Solstice Park, Amesbury, taking influence from white horses.[36]

The Westbury White Horse is depicted on a roundabout and mosaic in the town.[citation needed]

An 1872 sketch of the Cherhill White Horse was incorporated into an unofficial flag of Wiltshire.

The Town Flag of Pewsey, registered in September 2014, features the Pewsey White Horse at its centre.[citation needed]

Gallery

[edit]-

The Cherhill White Horse near Cherhill

-

Lenham Cross on the North Downs in Kent

-

Figure of a lion cut into the hillside: the Whipsnade Zoo lion near Whipsnade

-

Outline of a crown cut into the hillside. Wye Crown, at Wye, Kent

-

An offwhite triangle cut into the hillside. Watlington White Mark

-

Three military badges from the Fovant badges

-

A kiwi cut into the hillside. The Bulford Kiwi near Bulford

-

A white cross cut into the hillside. Whiteleaf Cross

-

The Mormond Hill White Stag, near Fraserburgh, Aberdeenshire

-

Hackpen White Horse

-

Pendle Hill marked with the date 1612 on the 400th anniversary of the Witch Trials

-

The Cherhill White Horse in 1892

-

The Westbury White Horse in 1772 (top) and as re-cut in 1778 (bottom)

-

The Uffington White Horse in 1885.

-

Layout of the Long Man of Wilmington

-

Layout of the Uffington White Horse

-

Layout of the Cerne Abbas Giant

In popular culture

[edit]Poetry and prose

[edit]- The Ballad of the White Horse by G. K. Chesterton

- The Scouring of the White Horse by Tom Hughes

- Sun Horse, Moon Horse by Rosemary Sutcliff

- Witch Hill by Marcus Sedgwick

- Find the White Horse by Dick King-Smith

- A Hat Full of Sky by Terry Pratchett

- The Dark Is Rising Sequence by Susan Cooper

- The Sandman by Neil Gaiman

- The Language of Bees by Laurie R. King

- The Westbury White Horse is mentioned in the novel The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje, but was not featured in the film of the novel.

Music videos

[edit]- Alton Barnes White Horse appears, very briefly, in the music video for Staying Out for the Summer by Dodgy.[38]

- Cherhill White Horse features in the music video for Doctorin' the Tardis by The Timelords.

- Uffington White Horse (in animated form) features in the music video for Sonnet by The Verve.

- Westbury White Horse features in the music video for Breathe by Midge Ure, alongside a temporary figure of the sun.

See also

[edit]- Anglo-Saxon paganism

- English folklore

- Gog Magog Hills, an unverified claim of geoglyphs

- Hillside letters, a similar type of geoglyph common in the Western U.S., but using letters instead of figures

- Nazca Lines, geoglyphs etched into the Nazca Plain

- White horse (mythology)

References

[edit]- ^ Nigel Clarke, The Rude Man of Cerne Abbas and Other Wessex Oddities, Lyme Regis, Nigel J. Clarke Publications, ISBN 978-0-907683-07-0

- ^ a b c d e "Cerne Abbas Giant". sacred-destinations.com. Archived from the original on 2021-03-19. Retrieved 2009-03-28.

- ^ "Wiltshire White Horses". wiltshirewhitehorses.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2009-04-05. Retrieved 2009-11-05.

- ^ "Roundway Hill and covert, Oliver's castle and Millennium White Horse". devizeheritage.org.uk. Archived from the original on 4 March 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ "Volunteers restore Australian map to Wiltshire hillside". Retrieved 2024-07-29.

- ^ Morris Marples, "White horses and other hill figures", Publisher: A. Sutton, 1949 (reprint), ISBN 0904387593, 9780904387599, 223 pages, page 16

- ^ John Timpson, "Timpson's Other England: A Look at the Unusual and the Definitely Odd", Publisher: Jarrold, 1994, ISBN 071170645X, 9780711706453, 224 pages, page 68 Archived 2024-05-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Harold William Timperley, "The Vale of Pewsey", Publisher Hale, 1954, 230 pages, page 181 Archived 2024-05-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Top 10: Britain's largest hill figures", The Telegraph, undated, attributed to Top 10 of Britain: 250 Quintessentially British Lists by Russell Ash, published by Hamlyn

- ^ a b Hows, Mark. "Lost Figures". Hillfigure site. Archived from the original on 2014-08-06. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- ^ a b Bergamar, Kate (1997). Discovering Hill Figures. Pub. Shire. ISBN 0-7478-0345-5.

- ^ "Prehistorical Wiltshire". fortunecity.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2004. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ "Wayside of Wiltshire". Bed & Breakfast and Self Catering Holiday Accommodation in beautiful Wiltshire. Archived from the original on 2013-04-10.

- ^ Hutchins, John (1973) [1742]. The History and Antiquities of the County of Dorset. Robert Douch (Contributor). Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0-87471-336-6.

- ^ "Cerne Giant in Dorset dates from Anglo-Saxon times, analysis suggests". 2021-05-12. Archived from the original on 2024-05-14. Retrieved 2021-05-12.

- ^ BBC (June 20, 2008). "Sheep shortage hits Giant's look". BBC. Archived from the original on 2021-02-11. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

- ^ Morris, Steven (2008-09-16). "Volunteers restore historic giant of Cerne Abbas to his former glory". The Guardian. Guardian Newspapers. Archived from the original on 2017-08-13. Retrieved 2008-09-17.

- ^ a b The Modern Antiquarian, Julian Cope, Thorsons 1998

- ^ Castleden, Rodney (2002). "Shape-shifting: The changing outline of the Long Man of Wilmington". Sussex Archaeological Collections. 140 (140): 83–95. doi:10.5284/1085966.

- ^ The Unknown, Issue Jan 1986

- ^ Derbyshire, David (2 October 2003). "Prehistoric Long Man is '16th century new boy'". Daily Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Archived from the original on 2012-11-11. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- ^ a b Gray, Todd (2003). Lost Devon: Creation, Change and Destruction over 500 Years. Exeter, Devon: The Mint Press. p. 153. ISBN 1-903356-32-6.

- ^ The Survey of Cornwall, text here:[1] Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine. Note that Carew refers to Plymouth Hoe as "the Hawe at Plymmouth".

- ^ Bracken, C. W. (1931). A History of Plymouth and her Neighbours. Plymouth: Underhill. p. 4.

- ^ "Firle Corn". hows.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2012-02-22. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- ^ "Scraps of Folklore Collected by John Philipps Emslie, C. S. Burne, Folklore, Vol. 26, No. 2. (Jun. 30, 1915), pp. 153-170". Archived from the original on 2012-08-15. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- ^ "Wish for rain to wash away Homer". BBC News. 2007-07-16. Archived from the original on 2014-07-15. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- ^ Hamblin, Cory (2009). Serket's Movies: Commentary and Trivia on 444 Movies. Dorrance Publishing. p. 327. ISBN 9781434996053. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ "Hillfigures.co.uk - A site dedicated to information about hill figures". www.hillfigures.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2022-08-13. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ^ Clark, John (2016). "Trojans at Totnes and Giants on the Hoe: Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historical Fiction and Geographical Reality". Report and Transactions of the Devonshire Association. 148. The Devonshire Association: 110. ISSN 0309-7994. Archived from the original on 2022-11-05. Retrieved 2022-11-05.

- ^ Clark, John (2016). "Trojans at Totnes and Giants on the Hoe: Geoffrey of Monmouth, Historical Fiction and Geographical Reality". Report and Transactions of the Devonshire Association. 148. The Devonshire Association: 108–111. ISSN 0309-7994. Archived from the original on 2022-11-05. Retrieved 2022-11-05.

- ^ "You Know You've Spent Too Long in Tameside If… | East of the M60". Archived from the original on 2016-10-14. Retrieved 2016-09-30.

- ^ "Waimate White Horse". Archived from the original on 2022-01-29. Retrieved 2022-05-21.

- ^ Bergamar, Kate (1997). Discovering Hill Figures. Pub. Shire. ISBN 0-7478-0345-5. P. 10 - 12.

- ^ "Staying in the public eye". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24.

- ^ "Solstice Park Slstice" (PDF). Solsticepark.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 24, 2022. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ^ "Lamb Down Military Badge". hows.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2015-01-10. Retrieved 2014-09-26.

- ^ Staying Out For The Summer - Dodgy on YouTube

Bibliography

[edit]- Newman, Paul (1997). Lost Gods of Albion: The Chalk Hill-Figures of Britain (2nd ed.). Stroud: Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-1563-3.

- Plenderleath, W C (1892). The White Horses of the West of England (2nd ed.). London: Allen & Storr.

![The Lamb Down Badge, near Codford, Wiltshire[37]](/media/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7c/Hill_Figure_over_looking_Foxholes_Bottom_and_the_A36_-_geograph.org.uk_-_327177.jpg/200px-Hill_Figure_over_looking_Foxholes_Bottom_and_the_A36_-_geograph.org.uk_-_327177.jpg)