Presidio of San Francisco

Presidio of San Francisco | |

|---|---|

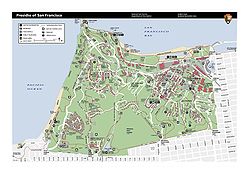

A map of the Presidio | |

| Coordinates: 37°47′53″N 122°27′57″W / 37.79806°N 122.46583°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City-county | San Francisco |

| Fortified | September 17, 1776 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Board of Supervisors |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.4 sq mi (6 km2) |

| Population (2019)[1] | |

| • Total | 4,226 |

| • Density | 1,800/sq mi (680/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 94129 |

| Area codes | 415/628 |

Presidio of San Francisco | |

| Area | 1,480 acres (6.0 km2)[3] |

| Built | 1776 |

| Architect | Spanish/Mexico/United States Army |

| Architectural style | Spanish Colonial, Spanish Revival, Colonial Revival, Classical Revival |

| Website | Presidio of San Francisco Presidio Trust |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000232[2] |

| CHISL No. | 79 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHL | June 13, 1962[5] |

| Designated CHISL | 1933[4] |

The Presidio of San Francisco (originally, El Presidio Real de San Francisco or The Royal Fortress of Saint Francis) is a park and former U.S. Army post on the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula in San Francisco, California, and is part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

It had been a fortified location since September 17, 1776, when New Spain established the presidio to gain a foothold in Alta California and the San Francisco Bay. It passed to Mexico in 1820, which in turn passed to the United States in 1848.[6] As part of a military reduction program under the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) process from 1988, Congress voted to end the Presidio's status as an active military installation of the U.S. Army.[7] On October 1, 1994, it was transferred to the National Park Service, ending 219 years of military use and beginning its next phase of mixed commercial and public use.[8]

In 1996, the United States Congress created the Presidio Trust to oversee and manage the interior 80% of the park's lands, with the National Park Service managing the coastal 20%.[9] In a first-of-its-kind structure, Congress mandated that the Presidio Trust make the Presidio financially self-sufficient by 2013. The Presidio achieved the goal in 2005, eight years ahead of the deadline.[10]

The park has many wooded areas, hills, and scenic vistas overlooking the Golden Gate Bridge, San Francisco Bay, and the Pacific Ocean. It was recognized as a California Historical Landmark in 1933 and as a National Historic Landmark in 1962.[5][4]

History

[edit]Military use

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2014) |

The Presidio was originally a Spanish fort sited by Juan Bautista de Anza on March 28, 1776, built by a party led by José Joaquín Moraga later that year. The limestone used to build the presidio was mined by Ohlones at the Rockaway Quarry.[11] In 1783, the Presidio's garrison numbered only 33 men. Upon Mexican independence from Spain in 1821, it was briefly operated as a Mexican fortification.

The Presidio was seized by the U.S. military at the start of the Mexican–American War in 1846. It was officially reopened by the Americans in 1848 and became home to several army headquarters and units, the last being the United States 6th Army. Several famous U.S. generals, such as William Tecumseh Sherman, George Henry Thomas, and John J. Pershing, made their homes here.

During its long history, the Presidio was involved in most of America's military engagements in the Pacific Rim. Importantly, it was the assembly point for army forces that invaded the Philippines during the Spanish–American War, America's first significant military engagement in the region.

Beginning in the 1890s, the Presidio was home to the Letterman Army Medical Center (LAMC), named in 1911 for Jonathan Letterman, the medical director of the Civil War–era Army of the Potomac. LAMC provided thousands of war-wounded with high-quality medical care during every US foreign conflict of the 20th century.

One of the last two remaining cemeteries within the city's limits is the San Francisco National Cemetery. Among the military personnel interred there are General Frederick Funston, hero of the Spanish–American War, Philippine–American War, and commanding officer of the Presidio at the time of the 1906 earthquake; and General Irvin McDowell, a Union Army commander who lost the First Battle of Bull Run.

The Marine Hospital operated a cemetery for merchant seamen approximately 100–250 yards (91–229 m) from the hospital property. Based on city municipal records, historians estimate that the cemetery was used from 1885 to 1912.[12] As part of the "Trails Forever" initiative, the Parks Conservancy, the National Park Service, and the Presidio Trust partnered to build a walking trail along the south side of the site featuring interpretive signage about its history.[13]

The Presidio was the home of the Western Defense Command headquarters during World War II. It was here that Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt signed 108 Civilian Exclusion Orders and directives for the internment of Japanese Americans under the authority of Executive Order 9066 signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942.[14]

The Presidio sent its few remaining units to war for the last time in 1991 for Desert Storm, the First Gulf War. The role of the Sixth Army was the management of training and coordinating deployment of Army National Guard and U.S. Army Reserve units in the Western U.S. for Operation Desert Storm.

Preservation

[edit]After a hard-fought battle, the Presidio averted being sold at auction and came under the management of the Presidio Trust, a U.S. government corporation established by an act of Congress in 1996.[10][15][failed verification]

The Presidio Trust now manages most of the park in partnership with the National Park Service. The trust has jurisdiction over the interior of 80 percent of the Presidio, including nearly all its historic structures. The National Park Service manages coastal areas. Primary law enforcement throughout the Presidio is the jurisdiction of the United States Park Police.

One of the main objectives of the Presidio Trust's program was achieving financial self-sufficiency by fiscal year 2013, which was reached in 2006. Immediately after its inception, the trust began preparing rehabilitation plans for the park. Many areas had to be decontaminated before being prepared for public use.

The Presidio Trust Act calls for the "preservation of the cultural and historic integrity of the Presidio for public use." The Act also requires that the Presidio Trust be financially self-sufficient by 2013. These imperatives have resulted in numerous conflicts between the need to maximize income by leasing historic buildings and permitting public use despite most structures being rented privately. Further differences have arisen from the divergent needs to preserve the integrity of the National Historic Landmark District in the face of new construction, competing pressures for natural habitat restoration, and requirements for commercial purposes that impede public access.

Crissy Field, a former airfield, has undergone extensive restoration and is now a popular recreational area. It borders on the San Francisco Marina in the east and on the Golden Gate Bridge in the west.

The park has a large inventory of approximately 800 buildings, many of them historical. By 2004, about 50% of the buildings on park grounds had been restored and partially remodeled. The Presidio Trust has contracted commercial real estate management companies to help attract and retain residential and commercial tenants. The total capacity is estimated at 5,000 residents when all buildings have been rehabilitated. Among the Presidio's residents is The Bay School of San Francisco, a private, coeducational college preparatory school located in the central Main Post area. Others include The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Tides Foundation, the Arion Press, Sports Basement Presidio, and The Walt Disney Family Museum, a museum in the memory of Walt Disney.[16] Many various commercial enterprises also lease buildings on the Presidio.

The Thoreau Center for Sustainability preserved sections of the Letterman Army Hospital .[17]

The Presidio of San Francisco is the only site in a national recreation area with an extensive residential leasing program.

The Presidio has four creeks that park stewards and volunteers are restoring to expand their riparian habitats' former extents. The creeks are Lobos and Dragonfly creeks, El Polin Spring, and Coyote Gulch.

1990s – present

[edit]

The Trust entered a significant agreement with Lucasfilm to build a new facility called the Letterman Digital Arts Center (LDAC), which is now Lucasfilm's corporate headquarters. The site replaced portions of what was the Letterman Hospital. George Lucas won the development rights for 15 acres (6.1 ha) of the Presidio, in June 1999, after beating out several rival plans, including a leading proposal by the Shorenstein Company. LDAC replaced the former Lucasfilm headquarters in San Rafael. The $300 million development includes nearly 900,000 square feet (84,000 m2) of office space and a 150,000-square-foot (14,000 m2) underground parking garage with a capacity of 2,500 employees. Lucasfilm's Industrial Light & Magic, Lucas Licensing, and Lucas Online divisions reside at the site. George Lucas's proposal included plans for a high-tech Presidio museum and a 7-acre (2.8 ha) "Great Lawn" that is now open to the public.

In 2007, Donald Fisher, founder of the Gap clothing stores and former board member of the Presidio Trust, announced a plan to build a 100,000-square-foot (9,300 m2) museum tentatively named the Contemporary Art Museum of the Presidio, to house his art collection. Due to opposition,[18] Fisher withdrew his plans to build the museum in the Presidio and instead donated the art to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art before he died in 2009.[19][20]

As the Doyle Drive viaduct was deemed seismically unsafe and obsolete, construction started on the demolition of Doyle Drive in 2008 to replace the structure with a flat, broad-lane highway with a tunnel through the bluffs above Crissy Field, called the Presidio Parkway. The project cost $1 billion and was scheduled to be completed by 2016.[21][22]

The Trust plans to create a promenade that will link the Lombard Gate and the new Lucasfilm campus to the Main Post and, ultimately, to the Golden Gate Bridge. The promenade is part of a trail expansion plan that will add 24 miles (39 km) of new pathways and eight scenic overlooks throughout the park.

In October 2008, artist Andy Goldsworthy constructed the first of a series of sculptures in the Presidio, the Spire. It is 100 feet (30 m) tall and located near the Arguello Gate. It represents the tree replanting effort that has been underway at the Presidio.[23] Spire was followed by Wood Line in 2011,[24] Tree Fall in 2013,[25] and Earth Wall in 2014.[26]

In 2010, a trampoline park called House of Air was built using an old aircraft hangar.[27]

As of 2023, it is estimated that there may be at least four coyote families living in the park.[28]

Presidio visitor centers

[edit]

The visitor centers are operated by the National Park Service:

- Presidio Visitor Center: offers changing exhibits about the Presidio, information about sights and activities in the park, and a bookstore. The Presidio Transit Center is located adjacent to this visitor center and is served by the Presidio Go Shuttle and Muni bus routes.

- Battery Chamberlin: seacoast defense museum and artillery display at Baker Beach built in 1904.

- Fort Point: 1861 brick and granite fortification under the Golden Gate Bridge. The visitor center, open on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, offers video orientations, guided tours, self-guiding materials, exhibits, and a bookstore.

- Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary Visitor Center: This center offers hands-on marine-life exhibits and is located in a historic Coast Guard Station at the west end of Crissy Field. The building was used by the Coast Guard from 1890 to 1990.

- Golden Gate Bridge Pavilion: opened May 2012 for the 75th anniversary of the Golden Gate Bridge; the Pavilion is the first visitor center in the history of the Golden Gate Bridge. It is located just east of the southern end of the bridge.[29]

- Hidden Presidio Outdoor Track: begins at Julius Kahn Playground and encircles the valley just below it, 0.75 miles (1.21 km) of dirt trails, cutbacks, wooden stairs, and various altitudes.[30]

Crissy Field Center

[edit]Crissy Field Center (former Air Service/Air Corps/Army Air Forces airfield) is an urban environmental education center with programs for schools, public workshops, after-school programs, summer camps, and more. The center is operated by the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy and overlooks a restored tidal marsh. The facilities include interactive environmental exhibits, a media lab, a resource library, an art workshop, a science lab, a gathering room, a teaching kitchen, a café, and a bookstore.[31] The landscape of Crissy Field was designed by George Hargreaves. The project restored a naturally functioning and sustaining tidal wetland as a habitat for flora and fauna, previously not in the site's evidence. It also restored a historic grass airfield that became a culturally significant military airfield between 1919 and 1936. The park at Crissy Field expanded and widened the recreational opportunities of the existing 1+1⁄2-mile (2.4 km) San Francisco shore to a broader number of Presidio residents and visitors.

Presidio Tunnel Tops

[edit]

A major component of the Presidio's park attractions is the Presidio Tunnel Tops, which has created a 14-acre park (5.7 ha) on top of the tunneled portions of Doyle Drive.[32][33] The park contains several meadows and walking trails, along with viewpoints for major landmarks such as the Golden Gate Bridge. Negotiations between Caltrans, the San Francisco County Transportation Authority, and the Presidio Trust to finalize the land transfer for the park lasted from 2015 to 2018.[32] The budget for the park is $100 million, funded with public funds from the Presidio Trust and private contributions. The park opened for public use on July 17, 2022.[33]

Timeline

[edit]

- Pre-1776: The area was Ohlone land.

- 1776: Spanish Captain Juan Bautista de Anza led 193 soldiers, women, and children on a trek from present-day Tubac, Arizona, to San Francisco Bay.

- September 17, 1776: The Presidio began as a Spanish garrison to defend Spain's claim to San Francisco Bay and to support Mission Dolores; it was the northernmost outpost of New Spain in the declining Spanish Empire.

- 1794: Castillo de San Joaquin, an artillery emplacement was built above present-day Fort Point, San Francisco, complete with iron or bronze cannon. Six cannons may be seen in the Presidio today.

- 1776–1821: The Presidio was a simple fort made of adobe, brush, and wood. It often was damaged by earthquakes or heavy rains. In 1783, its company was only 33 men. Presidio soldiers' duties were to support Mission Dolores by controlling Indian workers in the Mission and farming, ranching, and hunting to supply themselves and their families. Support from Spanish authorities in Mexico was minimal.

- 1821: Mexico became independent of Spain. The Presidio received even less support from Mexico. Residents of Alta California, which included the Presidio, debated separating from Mexico.

- January 1827: Minor earthquake in San Francisco; some buildings were damaged extensively.[34]

- 1835: The Presidio garrison, led by Mariano Vallejo, relocated to Sonoma. A small detachment remained at the Presidio, which was in decline.

- 1846: American settlers and adventurers in Sonoma staged the Bear Flag Revolt against Mexican rule. Mariano Vallejo was imprisoned for a brief time. Lieutenant John C. Fremont, a U.S. Army officer, with a small detachment of soldiers and frontiersmen, crossed the Golden Gate in a boat to "capture" the Presidio unresisted. A cannon that Fremont spiked remains on the Presidio today.

- 1846–1848: The U.S. Army occupied the Presidio. The Presidio began a long era directing operations to control and protect Native Americans as headquarters for scattered Army units on the West Coast.

- 1853: Work was begun on Fort Point, which became a fine example of coastal defenses of its time. Fort Point, located at the foot of the Golden Gate in the Presidio, was the keystone of an elaborate network of fortifications to defend San Francisco Bay. These fortifications now reflect 150 years of military concern for the defense of the West Coast.

- 1861–1865: The American Civil War involved the Presidio. Colonel Albert Sydney Johnston protected Union weapons from being taken by Southern sympathizers in San Francisco. Later, he resigned from the Union Army and became a general in the Confederate Army. He was killed at the Battle of Shiloh. The Presidio organized regiments of volunteers for the Civil War and to control Indians in California and Oregon during the absence of federal troops.

- 1869–1870: Major General George Henry Thomas, an American Civil War hero, led the Division of the Pacific. General Thomas died in 1870 and was buried in Troy, New York.

- 1872–1873: Modoc Indian Campaign involved some Presidio troops and command in this significant battle, the last large-scale U.S. Army operation against Native Americans in the Far West.

- 1890–1914: Presidio soldiers became the nation's first "park rangers" by patrolling the new Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks.

- 1898–1906: The Presidio became the nation's center for assembling, training, and shipping out forces to the Spanish–American War in the Philippine Islands and the subsequent Philippine–American War (Philippine Insurrection). Letterman Army Hospital was modernized and expanded to care for the many wounded and seriously ill soldiers from these campaigns. The Philippine campaign was an early major U.S. military intervention in the Asia/Pacific region. Camp Merriam, located just north of the presidio, was established to train and house volunteers for service during the Spanish-American War.[35]

- 1903: President Theodore Roosevelt visited the Presidio. His honor guard was from the African American "Buffalo Soldier" 9th Cavalry Regiment, then at the Presidio.[36][37] This regiment took a role in Roosevelt's famous charge of San Juan Hill in Cuba.

- 1906: The San Francisco earthquake of April 1906 led to an immediate Army response directed by General Frederick Funston, who had earned the Medal of Honor for his bravery in the Philippines. Army units provided security and fought fires at the direction of the city government. After the fire that resulted from the earthquake, Presidio soldiers gave aid, food, and shelter to refugees. Temporary camps for refugees were set up in the Presidio.

- 1912: Fort Winfield Scott was established in the western part of the Presidio as a coast artillery post and the headquarters of the Artillery District of San Francisco.

- 1914–1916: The Presidio Commander, General John J. Pershing, commanded the Mexican Punitive Expedition to eliminate the threat of Pancho Villa, a Mexican rebel and bandit, who conducted raids across the U.S. border. General Pershing's family died in a tragic fire while he was away. As a result of the 1915 fire in General Pershing's quarters, the Presidio Fire Department was established as the first fire station staffed 24 hours per day on a military post.

- 1915: Part of the Panama–Pacific International Exposition was located on the Presidio waterfront, which was expanded by a landfill for the purpose. Soldiers supported the Exposition with parades, honor guards, and artillery demonstrations. The Exposition was to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal.

- 1917–1918: The Presidio rapidly expanded with new cantonments and training areas for World War I. Recruiting, training, and deploying units again become the Presidio's role. An officer training camp was located here. Quickly assembled buildings covered the waterfront area, and the railroad track into the Presidio was busy with wartime traffic. During the war, the 30th Infantry Regiment, "San Francisco's Own", whose motto, "OUR COUNTRY NOT OURSELVES", fought with distinction in World War I as a key fighting element of the 3rd Infantry Division who earned the title "Rock of the Marne". The 30th Infantry Regiment was frequently based at the Presidio.

- 1918–1920: The Presidio was the center for forming and training the American Expeditionary Force Siberia. This little-remembered force moved into Siberia during the Russian Civil War. The mission of this force changed often. It encountered hostility from another part of the Expeditionary Force, Japan, while fighting bandits and protecting Allied civilians.

- 1920–1932: The Presidio became home to Crissy Field, the major pioneering military aviation field located on the West Coast. Trailbreaking transpacific and transcontinental flights occurred here. At Crissy, future General "Hap" Arnold developed techniques for the new military aviation. Arnold later commanded the Army Air Corps and Army Air Forces in World War II.

- 1941–1946: World War II saw intense activity at the Presidio. It continued as a coordinating headquarters, deployment center, and training site, as it was for most of its existence. The Western Defense Command was responsible for the defense of the West Coast. This included supervising combat in the Aleutian Islands for a time. The Presidio again was crowded with temporary barracks and training facilities. Letterman Army Hospital was filled with casualties. At one point, entire trains filled with war-wounded arrived at the Presidio from the battles of Okinawa and Iwo Jima. A Japanese Language School was set up to train Japanese Americans to be interpreters in the war against Japan. Ironically, some of these soldiers' families were interned in camps for the rest of the war while they performed bravely in the Pacific.

- 1941–1945: The Commanding General of the Western Defense Command, General John L. DeWitt, responded to public hysteria directed against all Japanese on the West Coast. He recommended removing all Japanese, including citizens, from the Western Seaboard. The Federal Bureau of Investigation and some Western politicians also expressed alarm, although no incidents of sabotage occurred. President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, to direct removal of ethnic Japanese residents to internment camps.

- 1946: After World War II, the Presidio command was redesignated the Sixth Army under the leadership of General Joseph Stilwell. Again, it was responsible for all U.S. Army forces in the Western U.S., including training, supplies, and deployment. It also was the federal agency to coordinate disaster relief by the military. During this year, President Harry Truman had offered the Presidio as the site for the future United Nations Headquarters.[38] A United Nations Committee visited the Presidio to examine its suitability for the site, but the UN General Assembly ultimately voted in favor of its current New York City location instead.[39]

- 1950–1953: The Korean War tasked the Presidio's headquarters and support functions. Letterman Army Hospital was mobilized to care for casualties from the war.

- 1951: The Presidio hosted ceremonies for signing the ANZUS Treaty, a security pact of Australia, New Zealand, and the U.S. The Japan-US security treaty was signed at the Presidio, while the Japanese Peace Treaty was signed in downtown San Francisco.

- 1961–1973: The Presidio filled a supporting role during the Vietnam War. Antiwar demonstrations took place at the Presidio's gates.

- 1968: Richard Bunch shot, initiating the Presidio mutiny at the Presidio stockade prison. The XV Corps Deactivated.

- 1969–1974: Letterman Army Hospital (LAMC) was modernized, and Letterman Army Institute of Research (LAIR) was built.

- 1991: The Presidio sent its few remaining units to war for the last time in Desert Storm, the First Gulf War. The role of the Sixth Army was the management of training and coordinating deployment of Army National Guard and U.S. Army Reserve units in the Western U.S. for Operation Desert Storm.

- 1994: Sixth Army was inactivated, and the Presidio closed as an active U.S. Army installation per BRAC. The Presidio was transferred to the National Park Service.

- 1996: Presidio Trust was created to manage the park as part of the Omnibus Parks and Public Lands Management Act of 1996 by the 104th United States Congress. [citation needed]

- 1996–2009: The Internet Archive's headquarters were located in Building 116[40] from its founding until 2009.[41]

- 2001: Letterman Army Hospital was demolished. Later, the Letterman Digital Arts Center was constructed on the site.

Muwekma Ohlone singing at ribbon-cutting ceremony of the Presidio Visitor Center - 2001: Heavy metal band Metallica with their producer, Bob Rock recorded demos for their 8th studio album, St. Anger and recorded 9 unreleased songs and jams that were featured in their 2004 documentary, Metallica: Some Kind Of Monster.

- 2005: The Bay School of San Francisco opens in Building 35.

- 2009–2015: Doyle Drive Replacement Project – Demolition of the Doyle Drive viaduct, to be replaced by an eight-lane boulevard, including two pairs of tunnels between Crissy Field and the Main Post and a pair of elevated viaducts, at a total project cost of approximately $1 billion. The original Doyle Drive was demolished on April 27–30, 2012.

- 2017: The William Penn Mott Jr. Presidio Visitor Center was opened to the public and is meant to be a focal point for visitors to explore the 1,500 acres (610 ha) of the Presidio grounds. The center is operated by the National Park Service, the Presidio Trust, and the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy.[42][43][44]

See also

[edit]- 49-Mile Scenic Drive

- Military Districts in Spanish California

- Rancho San Ramon (Amador)

- List of beaches in California

- List of California state parks

- Bibliography of California history

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Census Tract 601, San Francisco, CA". Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ "Presidio of San Francisco" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-25. Retrieved 2012-01-17.

- ^ a b "Presidio of San Francisco". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ^ a b NHL Summary.

- ^ "Under Three Flags" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-01-17.

- ^ U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command Headquarters (2008). USAMRMC: 50 Years of Dedication to the Warfighter : 1958-2008. p. 121.

- ^ "Presidio of San Francisco Post to Park transition". National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ^ "The Presidio Trust". Archived from the original on February 14, 2012.

- ^ a b Levy, Dan (June 19, 2005). "A Green Belt in The Black". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-12-20.

- ^ "Historic Resource Study for Golden Gate National Recreation Area in San Mateo County" (PDF). National Park Service. Department of Interior. Retrieved 4 August 2023.

- ^ McCann, Jennifer (2006). "The Marine Hospital Cemetery, Presidio of San Francisco, California" (PDF). The Presidio Archaeology Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 9, 2012.

- ^ "The Marine Hospital Cemetery". The Presidio Trust. Archived from the original on September 16, 2012. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ "Remembering Executive Order 9066 – Golden Gate National Recreation Area (U.S. National Park Service)". National Park Service. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ "Title unknown". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "The Walt Disney Family Museum". Retrieved 2012-08-05.

- ^ "Thoreau Center for Sustainability San Francisco". Archived from the original on 2012-07-11. Retrieved 2012-08-05.

- ^ King, John (March 18, 2008). "Architect waxes poetic with Presidio museum". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2012-08-05.

- ^ King, John (July 2, 2009). "Fishers give up on plan for Presidio art museum". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2012-08-05.

- ^ Baker, Kenneth (October 2, 2009). "SFMOMA gets Fisher art collection". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2012-08-05.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (January 12, 2010). "Closure of Doyle Drive off-ramp goes smoothly". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2012-08-05.

- ^ "Presidio Parkway Construction Schedule". presidioparkway.org. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ ""Spire" by Andy Goldsworthy". Presidio Trust web site. Archived from the original on May 12, 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-05.

- ^ "Andy Goldsworthy's Wood Line". The Presidio Trust. 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "Andy Goldsworthy's Tree Fall". The Presidio Trust. 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "Andy Goldsworthy's Earth Wall". The Presidio Trust. 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "Presidio House of Air brings flight to the flightless". blog.sfgate.com.

- ^ "Coyotes in the Presidio". Presidio. Retrieved 2023-07-18.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (May 8, 2012). "Golden Gate Bridge's 1st visitor center to open". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2012-05-13.

- ^ Krupa, Maya. "Hidden Presidio Outdoor Track". Retrieved 2017-10-08.

- ^ "Crissy Field Center". Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. Retrieved 2012-05-01.

- ^ a b Dineen, J.K. (2018-06-13). "Above the bay, Presidio Tunnel Tops includes meadows, picnic areas, overlooks, daily mobile food and beverage vendors, and a youth area that includes the Field Station, Crissy Field Center, and the Outpost – a nature play area. San Francisco". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2018-06-20.

- ^ a b Presido Trust. "Frequently Asked Questions". Retrieved 2018-06-20.

- ^ "K. T. Khlĕbnikov: A Look at a Half-Century of My Life". Syn otechestva: 311–312. 1836.

- ^ "Camp Merriam". Historic California Posts, Camps, Stations and Airfields. militarymuseum.org.

- ^ "Presidio Garrison". Presidio of San Francisco. National Park Service. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "Buffalo Soldiers: The First African American 'Park Rangers'". Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. February 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Walbridge, Mark R. (1997). "The Presidio Trust". Urban Ecosystems. 1 (3): 133. doi:10.1023/A:1018519410163. S2CID 9853002.(subscription required)

- ^ "San Francisco's Proud Presidio". The Milwaukee Journal. December 17, 1946. Archived from the original on 2016-01-23. Retrieved 2012-08-05.

- ^ "DFG – GEPRIS – Internet Archive The Presidio of San Francisco". gepris-extern.dfg.de. Retrieved 2024-09-16.

- ^ Carroll, Rory (2013-04-26). "Brewster's trillions: Internet Archive strives to keep web history alive". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-09-16.

- ^ "New Presidio Visitor Center Debuts Saturday, February 25, 2017". www.nps.gov.

- ^ "New Presidio Visitor Center Debuts Saturday, February 25 – Golden Gate National Recreation Area (U.S. National Park Service". www.nps.gov).

- ^ "Presidio Visitor Center – Presidio of San Francisco (U.S. National Park)". www.presidio.gov.

- National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form and accompanying photos

- "Nomination Form" (pdf). National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. October 28, 1992.

- "Photos (78)" (pdf). National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. August 1990.

External links

[edit]- The National Park Service's official site of the Presidio

- The Presidio Trust

- The National Park Service's official site of the Golden Gate Recreation Area

- Moraga's Account of the Founding of San Francisco

- Discover Our Shared Heritage "Early History of the California Coast" National Park Service

- "Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail" National Park Service

- The California State Military Museum, on the Letterman Army Hospital

- El Presidio Digital Media Archive (creative commons-licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas), mainly The Officer's Club and Fort Scott, using data from a UC Berkeley/CyArk research partnership

- Fort Point and Presidio Historical Association

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. CA-1114, "Presidio of San Francisco, U.S. 101 and I-480, San Francisco, San Francisco County, CA", 8 photos

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. CA-155, "Presidio Water Treatment Plant, East of Lobos Creek at Baker Beach", 2 photos, 31 data pages, 1 photo caption page

- HAER No. CA-2296, "Presidio of San Francisco, Rail Line, North Cantonment, Between Mason Street and Halleck Street", 7 data pages

- Records of the Presidio Trust in the National Archives (Record Group 556)

- Presidio of San Francisco

- Golden Gate National Recreation Area

- Parks in San Francisco

- Museums in San Francisco

- California presidios

- Forts in California

- Historic American Buildings Survey in California

- Historic American Engineering Record in San Francisco

- Military facilities in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Forts on the National Register of Historic Places in California

- Military and war museums in California

- National Historic Landmarks in the San Francisco Bay Area

- National Register of Historic Places in San Francisco

- Natural history museums in California

- Open-air museums in California

- Former installations of the United States Army

- 1776 establishments in The Californias

- 1776 in The Californias

- San Francisco Bay Trail

- Bay Area Ridge Trail